Colleen Mondor's Blog, page 8

May 6, 2014

On words at a young age and John Muir

In nineteenth-century America and Europe, a time before television, telephones and the Internet, people read real books. They drank literature like water. The literacy rate was not high in some places, but in southern Scotland, along the Firth of Forth, from Dunbar to Edinburgh, where Muir spent his first eleven years, it was higher than 80 percent.

Among those who could read, books were prized possessions. Words on paper were powerful magic, seductive as music, sharp as a knife at times, or gentle as a kiss. Friendships and love affairs blossomed as men and women read to each other in summer meadows and winter kitchens. Pages were ambrosia in their hands. A new novel or collection of poems was something everybody talked about. Wordsworth, Coleridge, Shakespeare, Bronte, Austen, Dickens, Keats, Emerson, Cooper, Thoreau, Hawthorne, and Twain. To read these authors was to go on a grand adventure and see things as you never had before, see yourself as you never had before.

From John Muir and the Ice that Started the Fire by Kim Heacox. See my full review over at Alaska Dispatch.

[Photo from Nat Park Service of Glacier Nat Park.]

May 2, 2014

At the park, 1922

My grandmother, age 3, and her older brother Robie, age 6. I have a series of photos taken this day, with their two older brothers, parents and some sadly unidentified friends or family members.

From the way they are dressed it seems it must have been a special day and with no snow on the ground I'm inclined to think it is Easter. We always received new clothes for Easter and I'm sure the tradition was true for them as it was for us. (Even when Catholic families have little money, at the very least a new bow or gloves turn up in Easter photos.)

These two ended up bickering as the years went by - too close in age probably. Robie went on a motorcycle trip across country to California as a young man - pictures from that period will make you positively swoon.

April 30, 2014

Wherein I am utterly beguiled by "The People in the Photo"

Hélène Gerstern's upcoming novel, The People in the Photo, is absolutely sublime. Translated by Emily Boyce and Ros Schwartz, this epistolary tale is a family mystery, a sweet romance and a serious page-turner. It snuck up on me, plain and simple and I couldn't put it down.

Hélène Gerstern's upcoming novel, The People in the Photo, is absolutely sublime. Translated by Emily Boyce and Ros Schwartz, this epistolary tale is a family mystery, a sweet romance and a serious page-turner. It snuck up on me, plain and simple and I couldn't put it down.

The story is, on the surface, pretty simple. The main character (also named Hélène) lives in Paris where she works as an archivist. Her mother died when she was 4 and her father has also recently passed away. Her stepmother has Alzheimer's and is in longterm care. While going through her parents' apartment, she finds a picture of her mother with two men she does not recognize. She runs the photo in some French and Swiss newspapers as an advertisement asking if anyone recognizes the men or the sporting event (tennis) they participated in. Stéphane Crüsten responds that one of the men is his deceased father and the other his best friend.

In the letters that follow Hélène and Stéphane try to uncover how their parents came to know each other. More pictures are found and Stéphane visits the family friend in search of more clues. Bit by bit the two learn how their families were connected and the numerous secrets that are buried in the past. Also, bit by bit, they surprise themselves by falling in love thus providing a light romantic tension to the mystery.

Everything about The People in the Photo works. The pacing is fantastic - the buildup of the romance is subtle and true to the characters' restrained emotions. But even without that element (which I enjoyed very much), it is the slow unfolding of the past that keeps the pages turning. Finding out who these people in the photo were and what their level of involvement was and why on earth it has all been kept quiet (Hélène's mother died in a very prosaic way after all - a car crash), are questions that I really wanted answered. I also liked very much that Gerstern doesn't back away from ugly moments and gives readers the kind of emotional payoff that the story promises from the very beginning. The ending is powerful stuff and serves all the characters (past and present) well. There's just not a single disappointment to this novel; it's really a wonderful book.

And for me, of course, The People in the Photo brought to mind all the secrets hidden in my own family photos; all of the faces I look at now that hide so much from decades ago. I know many of these secrets, others I am still hoping to uncover. I identified a great deal with Hélène and Stéphane and their search for the truth and I can tell you, all of it rings powerfully true.

April 28, 2014

Not knowing "where I was from"

I have just reread Joan Didion's Where I Was From - giving it a "deep" read this time. It is a collection of related essays about Didion's personal history and the history of California, where she grew up. Reading it has made me realize how confusing my own answer would be to the question, if asked, of "Where are you from?"

I grew up, from age 3, in Florida.

We lived in Jacksonville (in a haunted house) and then Orlando and then, from my 5th birthday, in Melbourne. Very nearly all my childhood memories are of the beach and palm trees and flat roads and hot sun and ceiling fans and sweet ice tea and hush puppies and rocket ships. (They call it the Space Coast for a reason.)

Yet this is not really, truly, where I am from.

My father was born and raised in a solidly Catholic and most assuredly French Canadian town in Rhode Island and although he left at 17 he was so much a part of his home that he received the local newspaper for the rest of his life. When we go back to Woonsocket it is to hear his voice in the speech of everyone around us, to be surrounded by my father's people. To be surrounded by our people.

I have a maple leaf tattooed on my right wrist for my French Canadian heart which still, even with him 15 years gone, beats for my father.

My mother was raised in an air force family and she would tell you she was from everywhere and nowhere as most military families would say. But both of her parents were from the Bronx and their roots go back years there in Irish American households and families, in song and dance and laughter and a thousand kitchen conversations.

The shamrock on my left wrist is for my Irish soul; it's something you are born with and stays with you no matter where you live.

I have never been to the Bronx and only once to New York City. But most of my grandmother's family is still in New York State (all over including the city), and all of my genealogy research has involved NYC. My future may not be there but a large swath of my past most certainly is and it continues to be the center of learning who we are as a family and how we came to be Americans.

So you can see how this whole "where are you from" question is sort of confusing.

I do not have five generations in any one place; I have Florida and Rhode Island and Quebec or Florida and the Bronx and Ireland. My parents, remarkably, met and married in Madrid, Spain (my father was in the air force, my mother was there with her family as that was their latest station). The deep roots that Didion writes of are totally foreign to me and yet so much of her emotion for California, for exploring how the land formed who she became, resonated with me.

After the death of her mother (In California) she writes of going through her things:

I had my grandmother's watercolor framed and sent it to the next oldest of her three granddaughters, my cousin Brenda, in Sacramento.

I closed the box and put it in a closet.

There is no real way to deal with everything we lose.

And that was it. My grandparents gave up the Bronx when they committed to a military life and my father left Woonsocket behind partly out of desperation to see some other part of the world. And I left Florida for Alaska because as much as I love the beach, I wanted to go away. (It's funny - I still don't know why I wanted to go away.) But when I consider who we are - who I am - the answers are all found in Rhode Island and New York. I am surrounded by pictures of those places, by accents, by the memories of food and traditions, by the locations of so many weddings and funerals, all in Woonsocket and the Bronx.

Everything about the family I have known and loved is in those two places. Dealing with what we left, with what we lost by leaving, means immersing myself in places where I actually never lived. Florida gives me no answers on that score and so I have to wonder, is that the place where I am from or somehow, some way, am I more from places where I never lived?

April 25, 2014

"He wanted her not to be known as 'the Mary Anning of legend, something of a village blue-stocking,'..."'

I just finished reading Judith Pascoe's The Hummingbird Cabinet

which is about several romantic collectors and the sorts of things they collected (like hummingbirds). Lord Byron is a big player here and lots of other people I had not heard of but found quite interesting. Pascoe does a good job of taking readers through the lives of people who lived a long time ago and explaining what motivated them and their compatriots.

I was most struck by the chapter on Mary Anning however. Anning, (1799-1847), was not a romantic collector as you think of one - she collected fossils for money to support herself and her mother (and younger brother). Anning is, in fact, one of the most famous fossil collectors in history. A lot of very powerful museum men (and collectors) bought fossils from her. What they did not do is invite her into the scientific field that depended upon her fossils. She was always the collector - someone who got her hands dirty and had an uncanny ability to find fossils but not an archaeologist. Not a scientist. Not a peer.

No chance of that.

Pascoe attended a symposium on Anning in 1999 where a lot of very learned people talked about her and a lot of Anning fans (authors, artists, amateur collectors) listened. Pascoe was struck by the different ways in which the Anning "people" mixed...or didn't. And she writes about the discussion of the diaries of Anna Marie Pinney who met Anning in 1831. Anna Marie Pinney was younger and though she became a good friend of Anning's over the years, she was certainly struck by Anning; deeply impressed by her. She was a fan and wrote about her sometimes in a fannish sort of way.

As I am a fan of Mary Anning's, I can totally appreciate that!

But the scientists at the symposium were not so impressed by Anna Marie's recollections; a "hysterical teenager" is how one refers to her. Anning is supposed to be dedicated, "plain, practical, honest, humble" and not a literary figure, not someone brave and exciting, not (to choose a 20th century comparison), a female Indiana Jones uncovering mysteries by the sea.

Anna Marie's stories about her are just too dang exciting.

No one denigrates Anning's finds or belittles her, they just want her to be a certain kind of fossil collector, the kind that doesn't fill the head of teenage girls with big excitement. And honestly, Mary Anning wasn't a wild and crazy woman - she seems to have been a pretty serious individual carving out a living the way she knew best. But what struck me after reading The Hummingbird Cabinet is that even with all her seriousness, she still wasn't serious enough for some people. More than a 100 years after she died, there are still those that wanted to keep the lid on Mary's [mildly] wild ways.

I like Anna Marie's vision a lot more than theirs though. Mary Anning was brave and tough - she was a little bit Indiana Jones out there, fighting the wind and the sea for her fossils. She deserves to be remembered the way the people who knew her best really knew her. Points to Judith Pascoe for making sure we all know this side of Mary now as well.

[Post pic via..]

April 23, 2014

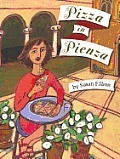

The story of pizza - really!

I have a deep appreciation for family food traditions. From my mother's side (Irish American) we don't have many. (The most enduring is easting Entenmann's Coffee Cake which I don't think really counts but we love it.) On my father's side (French Canadian) there are many because he was a great cook and my memere was as well (especially baking). But in terms of ethnic food, I don't know that anyone really sees something and yells "Oh, look! French Canadian food!" (If you can name any French Canadian food other than syrup right now, you deserve an award.)

I have a deep appreciation for family food traditions. From my mother's side (Irish American) we don't have many. (The most enduring is easting Entenmann's Coffee Cake which I don't think really counts but we love it.) On my father's side (French Canadian) there are many because he was a great cook and my memere was as well (especially baking). But in terms of ethnic food, I don't know that anyone really sees something and yells "Oh, look! French Canadian food!" (If you can name any French Canadian food other than syrup right now, you deserve an award.)

About now you probably understand that I spent a large part of my childhood wishing I was Chinese, Mexican or Italian solely for the food.

All of this explains why when I received a copy of the picture book Pizza in Pienza by Susan Fillion, I was delighted by each and every page. It's a very simple story about a girl in Pienza, Italy, who takes readers through her day and across her town. Along the way she shares her love of pizza, ("Even while I'm eating spaghetti, I'm dreaming about the next pizza pie."), and her research into the history of pizza which, as we know it, comes from Naples, Italy. The story comes around to America, where the first pizzeria opened in NYC in 1905 and the final spreads show people enjoying pizza both in the U.S. and Italy which is all kinds of wonderful.

Everyone would like to be a member of the ethnic group that invented pizza, don't you think?

Fillion both wrote and illustrated Pizza in Pienza and the illustrations are large and colorful, with a folk art feel. The story reads as a picture book travel essay and the dual text, with a single line on each page in both English and Italian, fits well in this narrative design. In the final pages the author includes a pronunciation page, a history of pizza and a recipe for Pizza Margherita (including the dough).

This is a decidedly quiet book but it provides a nice lesson about a well known topic while introducing a foreign country in a very accessible way. (That's the part that will appeal to folks looking for educational reads.) For me, it was quite reminiscent of all those delightful Italian memoirs for adults (paging Frances Mayes). It's one of the better ways to bring Italy home to kids and it will likely also spur them to appreciate their pizza even more which is always a good thing. Call this one a nice delightful and tasty trip for younger readers. :)

April 21, 2014

Circa 1915

My great grandmother Julia's two sisters, Ernestine (Tina) on left and Carolina (Carol) on right. This was taken about 1915 when Carol was 15 and Tina 20.

The two girls (and a third sister, Marie) shared a mother with my great grandmother but she had a different (and unknown) father. By all accounts Julia was fairly close with her younger half siblings however, and my mother can recall visiting her great aunts in the 1950s.

I am still working on the lives of these women. I know that they married and had children but I believe Tina's daughter (and grandson) died of diphtheria in the early 1930s and I have seen allusions to Carol losing a child (a son) as well. There are still, so many things I do not know about my family.

But still - look at them here. This picture was made into a postcard and taken, from the stamp on the back, at Schaffers Studio on the Boardwalk in Midland Beach, Staten Island. These historic postcards from the beach really make it look quite charming; I'm glad the girls had such a good time.

April 17, 2014

"I still see her standing by the water"

From Billboard magazine, yesterday:

Glen Campbell has been moved into a care facility three years after being diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease, People.com reports.

"He was moved to an Alzheimer's facility last week," a family friend told the title. "I'm not sure what the permanent plan is for him yet. We'll know more next week."

The singer, whose "Rhinestone Cowboy" topped the charts in 1975, had been suffering from short-term memory loss in recent years. He was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease in early 2011.

His voice, and the songs he made famous, are as much a part of America to me as the documents we hold so dear and the land we love so much. I never get tired of hearing him sing. I hope he has peace in his life in times ahead.

[Video from 2001 - it provides not only Glen singing "Galveston" but the brief story of the song, which was significantly linked to the Vietnam War. "Galveston" was written by Jimmy Webb.]

April 14, 2014

"In other words, Marie was not lauded. "

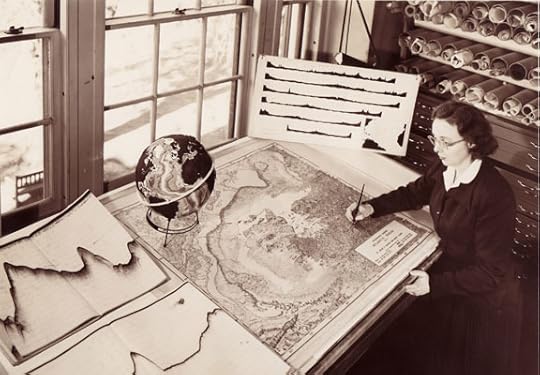

I read Soundings by Hali Felt and learned that Marie Tharp and Bruce Heezen (scientist and co-worker and partner in every sense of the word with Marie) literally mapped the ocean floor. I had never heard of either one of them before this. Had no idea that Maria took the soundings gathered by Heezen and others at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and drew the map - drew the map!!! - of the ocean floor.

I read Soundings by Hali Felt and learned that Marie Tharp and Bruce Heezen (scientist and co-worker and partner in every sense of the word with Marie) literally mapped the ocean floor. I had never heard of either one of them before this. Had no idea that Maria took the soundings gathered by Heezen and others at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and drew the map - drew the map!!! - of the ocean floor.

She was a cartographer of the ocean floor.

There is so much about Marie's career that blows my mind (here's a good overview in her obituary from Columbia University), but a couple of things stand out. First, is that she took data that had been sitting around for years and said "why don't we actually create a map from it?" (Basically.) And second that she looked at those maps and realized they were proving continental drift with the maps. Now, it seems obvious but then - the 1950s - it was heresy. (Even Heezen fought her initially.) But Marie hung in there and let the maps speak for themselves. Her work was irrefutable and could not be denied (though plenty of folks denied it for way too long.) She proved what poor Alfred Wegener had asserted in 1912 and she changed the field of oceanography.

I bet you have never heard of Marie Tharp though.

Hali Felt has a great blog post about Marie and what she would have thought about her work largely being undiscovered during her lifetime (and the struggle of her professional life).

It makes me both sad and happy that the record has finally be set straight. Marie is not here to enjoy Soundings; she doesn't know she has been discovered. There are likely so many other stories like hers out there, lost and waiting to be found by a curious reader. We fill our heads with so much that doesn't matter; and we forget people like Marie who really did change the world.

[Post pic of Marie Tharp - the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory]

April 6, 2014

The writer is bereft

This is my dog Hondo who died on Friday.

If you have ever been through it then you know what it's like to sit in the vet's office as your pet is diagnosed with an incurable disease. You start with the pain medication and you watch him limp and first he is just the same except for the limp but then he is slower to stand, slower to sit. He eats a little less and then sometimes, doesn't want to eat at all. He used to follow you everywhere you go and now he only does part of the time. He sleeps more but does not sleep well; he is restless. And you increase the pain medication and you entice with food that he loves and you lavish all the love in the world upon him and then you realize it's over; it's time.

He's telling you it is time.

And so you make the appointment and you go to the vet and they are all so sad because they love him too and you sit and you hold his head and he looks at you and he trusts you and he knows you will never ever do him wrong and you tell the vet to do it and just like that, in a moment, he is gone.

And eight years was really far too short.

Hondo had bone cancer. There was little we could do although we did as much as we could. I have been to the vet for a visit like this before, for Jake, (my Florida-born husky/shepherd/doberman mix who went north with me), who died in 2003 and for Tucker, (my Fairbanks-born Black Lab who came south with me), who died in 2007. Hondo was from an animal shelter in Washington State, a mix of German Shepherd, Black Lab and Rottweiler (we think) who was found on the side of the road with his mother and litter mates. He was the kindest dog I have ever known, a good dog in the purest sense of the world.

Of course, like every dog I have ever loved, he was special.

What I realized last night though, is that more than anything Hondo is the dog that I have written with. Late at night, after everyone else has gone to bed, Hondo sat with me while I put The Map of My Dead Pilots together. He was at my feet (always at my feet), with his paws wrapped around the chair legs, as I worked the rewrites my agent requested, then worked the rewrites my editor requested and then, finally, finished my book.

At the dining room table, writing essays and articles, Hondo was at my feet. If I got up and moved, downstairs to get a book I needed, into my office in search of a stray paper, he came with me. All the words that I produced that matter in the past 7+ years were with Hondo and now his loss to every aspect of my life is nearly overwhelming.

Writers always have rituals: you have the cup of tea in that mug, the plate of snacks arranged just so, the special writing desk or chair or notebook. You write in your office or the corner of your bedroom or out on the deck or in a backyard writing hut. You listen to certain music; you have an old movie that plays in the background. There are things that you do every time you write, habits that are part and parcel of the process. For me, Hondo was my writing companion, the one who heard the words before they were smooth, the one who stood up to urge a break, the one who patiently listened as I whined and complained my way through a stubborn paragraph. The words came with Hondo, they made sense with Hondo, they worked with Hondo and now I have no one to hear my words.

He was my dog, and I loved him. He was my friend and I mourn him. He was my heart and I can not imagine a world, or a word, without him.

My dog Hondo died on Friday, and I miss him very much.

Hondo at about 3 months old, the day we brought him home, July 2006.

Hondo at about 3 months old, the day we brought him home, July 2006.

bereft: adj. sad because a family member or friend has died