Colleen Mondor's Blog, page 19

March 11, 2013

Round-Up

What I'm reading now:

Soundings: The Story of the Remarkable Woman Who Mapped the Ocean Floor by Hali Felt. Really interesting biography of an unorthodox geologist and underwater cartographer. I'm loving how Felt wrote this book - she had to insert herself into it but explains how and why throughout the text. It's...like no other biography I've read; great stuff.

Chasing Alaska: A Portrait of the Last Frontier Then and Now by CB Bernard. For Booklist, so I can't say but the premise is quite intriguing.

What I just finished:

Deviant by Helen Fitzgerald. One of the titles from the new YA imprint at Soho Press. It's a conventional thriller in some regards - there is a conspiracy, the protagonist must figure things out, murders occur, etc. But the fact that it is conventional is part of what made me enjoy it so much. This is an actual teen mystery where absolutely nothing paranormal happens. It's all about a nefarious plot and there is a chase and sneaking into rooms at night and lying to cover your tracks and, well, pretty much what you expect in a mystery which makes Deviant so bloody refreshing. Most enjoyable - great protagonist! - will be reviewed in my June column.

Last week was mostly about another fatality crash in Alaska. I have things to write about that crash, things to write about flying in AK that are unrelated to crashing and just...things to write. It feels hard this week; so I need to try harder.

March 7, 2013

Thoughts while up late reading accident reports

Over past couple of weeks I've been working on this article about the Idiarod Air Force (IAF) for Alaska Dispatch. Just as it was about to go up on the site a privately owned aircraft that was not affiliated with the IAF went missing on Monday. I was up late that night working on that article with my editor and then Tuesday the wreckage was found - no survivors. So Tuesday I worked on an article about the previous dangerous aviation history in that area.

All of this necessitated reading a lot of old accident reports and weather reports and studying maps (I always want to study the maps - it helps me figure out what I'm writing about). None of it is anything new for me; the recent accident is very sad but I've been here before. They are always sad. While I've been doing this aviation stuff, I've been writing about mountain climbing (in 1910) and in both cases there has been a lot of wondering why men do the things they do. (I have not encountered many women in these particular questions lately, but I will ask the questions of women when they show up in my archival wanderings as well.)

Every accident happens for a very specific set of reasons. Weather might be a factor, or mechanical difficulties. The same can be said of mountain climbing (though the mechanical bits are not so dramatic). But while you can say a pilot continued into bad weather or a climber failed to turn around in the face of fading daylight (they hardly ever turn back when the summit is close), what you can't answer is why they were there in the first place. If they don't survive then you can't know what those thoughts were that propelled them to that certain place in that certain time. Just like all of us have our own reasons for marriage or school or jobs, so do pilots and mountain climbers.

The crash on Monday was about a dangerous pass and bad weather. The questions are why he chose that pass instead of the safer long way around and why he didn't turn back when it started getting bad. There are a lot of tried and true reasons that come to mind (arrogance, self-induced pressure, bush pilot syndrome, fear of failure, general obliviousness, etc.) but really, we will never know. A thousand things happened before he got in that plane to bring that pilot to that place and that crash. Even the people that know him best might not know all of his reasons. But every single time, every single crash report I read no matter how old, the question of why is what leaps to my mind.

I always want to know what I can never know. It should be frustrating but instead, it just makes me want to read and write more.

March 4, 2013

Considering Jemmy Button (& Andrea Barrett's thoughts on the subject)

I've been thinking lately about Jemmy Button.

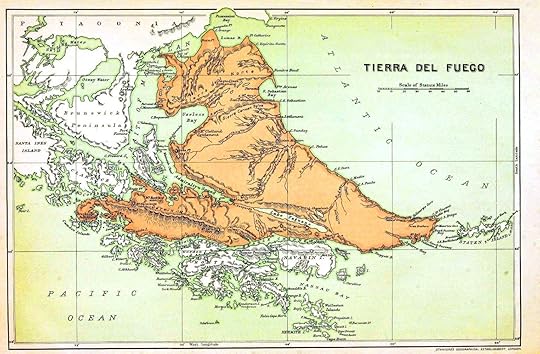

In 1830 the man who became known as Jemmy Button was taken, in apparent retaliation, with three other Fuegian people from Tierra del Fuego by Capt Robert Fitzroy of the HMS Beagle after one of the ship's launch boats was taken. They returned to Britain with the ship where one of them passed away from smallpox. In 1831 when the Beagle departed on another voyage (this time with Charles Darwin onboard), Fitzroy made the decision to take the three Fugians back home. It was not a warm welcome at first - at all - but eventually, after some difficult times, Jemmy and his friends were apparently integrated back into the village. The missionary that accompanied them was not so lucky (he demanded to leave with the Beagle when it stopped back by, apparently the grand plan to convert the whole village did not work out) but Jemmy Button is an example of a native who left his home and albeit quite painfully, found his way back. I knew his story but because of Andrea Barrett, I've been thinking about him a lot lately.

I have been reading a lot of Andrea Barrett these days. Her sense of history is what I'm trying to tap into and the way she blends science so effectively into her stories (and novels). It's her attention to detail that is really appealing to me as I try to find the right balance of detail in my own current (nonfiction) work on AK. In her short story "Soroche", (from Ship Fever), Barrett writes about a woman, Zaga, who moved away from her family's social and economic classes after she married. When her husband dies and she gives away/loses the fortune he left her, she struggles to integrate back into the people she left behind. Sometimes, it doesn't have to be miles to make the distance great.

Zaga remembers a conversation she had years before with a doctor about Jemmy Button. There was one exchange in particular she recalled:

Think of that. Jemmy Button: captured, exiled, re-educated; then returned, abused by his family, finally re-accepted. Was he happy? Or was he saying that as a way to spite his captors? Darwin never knew.

Barrett wants the reader to question if Zaga is happy - if she was happy in the strange new world with her husband (who she loved) and if she will be happy now, with her family who distrusts her because she left. Can you go that far away and still be who you are - still be who you think you are even when you go back home?

I think about that a lot.

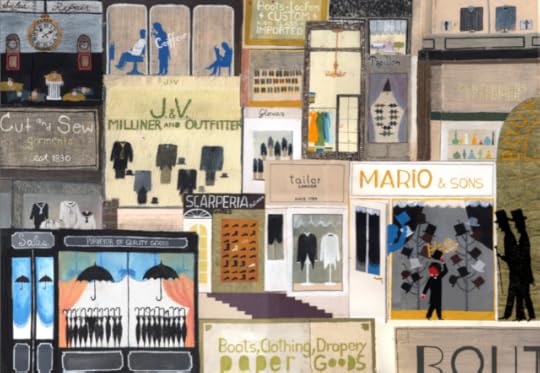

Templar Books has a picture book due out in a couple of months, called Jemmy Button , written by Alix Barzelay with illustrations by Jennifer Uman and Valerio Vidali. It is gorgeous to look at and the illustrators (who collaborated across the ocean without a common language) have done an outstanding job of showing Jemmy as someone apart in England, even when he is in the midst of a crowd. Barzelay's text tells the basic story although she spares young readers the drama of his return. "The island had remained the same," she writes, "as had the forest and the sky and the ocean." For young readers this is the Jemmy they want to know but it is of course not the whole story. The island had not changed but Jemmy had, he had become someone named Jemmy Button after all, and returning home was not as easy as walking on the same soil again.

Alaska is pretty far from the rest of the world; returning home from there isn't so easy either. So yeah, thinking a lot about Jemmy Button and Tierra del Fuego lately, while writing about Russ Merrill and more in Alaska.

[Interior shot from Jemmy Button after he arrives in London.]

Considering Jemmy Button (& Andrea Barrett's thoughts on the subject)

I've been thinking lately about Jemmy Button.

In 1830 the man who became known as Jemmy Button was taken, in apparent retaliation, with three other Fuegian people from Tierra del Fuego by Capt Robert Fitzroy of the HMS Beagle after one of the ship's launch boats was taken. They returned to Britain with the ship where one of them passed away from smallpox. In 1831 when the Beagle departed on another voyage (this time with Charles Darwin onboard), Fitzroy made the decision to take the three Fugians back home. It was not a warm welcome at first - at all - but eventually, after some difficult times, Jemmy and his friends were apparently integrated back into the village. The missionary that accompanied them was not so lucky (he demanded to leave with the Beagle when it stopped back by, apparently the grand plan to convert the whole village did not work out) but Jemmy Button is an example of a native who left his home and albeit quite painfully, found his way back. I knew his story but because of Andrea Barrett, I've been thinking about him a lot lately.

I have been reading a lot of Andrea Barrett these days. Her sense of history is what I'm trying to tap into and the way she blends science so effectively into her stories (and novels). It's her attention to detail that is really appealing to me as I try to find the right balance of detail in my own current (nonfiction) work on AK. In her short story "Soroche", (from Ship Fever), Barrett writes about a woman, Zaga, who moved away from her family's social and economic classes after she married. When her husband dies and she gives away/loses the fortune he left her, she struggles to integrate back into the people she left behind. Sometimes, it doesn't have to be miles to make the distance great.

Zaga remembers a conversation she had years before with a doctor about Jemmy Button. There was one exchange in particular she recalled:

Think of that. Jemmy Button: captured, exiled, re-educated; then returned, abused by his family, finally re-accepted. Was he happy? Or was he saying that as a way to spite his captors? Darwin never knew.

Barrett wants the reader to question if Zaga is happy - if she was happy in the strange new world with her husband (who she loved) and if she will be happy now, with her family who distrusts her because she left. Can you go that far away and still be who you are - still be who you think you are even when you go back home?

I think about that a lot.

Templar Books has a picture book due out in a couple of months, called Jemmy Button , written by Alix Barzelay with illustrations by Jennifer Uman and Valerio Vidali. It is gorgeous to look at and the illustrators (who collaborated across the ocean without a common language) have done an outstanding job of showing Jemmy as someone apart in England, even when he is in the midst of a crowd. Barzelay's text tells the basic story although she spares young readers the drama of his return. "The island had remained the same," she writes, "as had the forest and the sky and the ocean." For young readers this is the Jemmy they want to know but it is of course not the whole story. The island had not changed but Jemmy had, he had become someone named Jemmy Button after all, and returning home was not as easy as walking on the same soil again.

Alaska is pretty far from the rest of the world; returning home from there isn't so easy either. So yeah, thinking a lot about Jemmy Button and Tierra del Fuego lately, while writing about Russ Merrill and more in Alaska.

[Interior shot from Jemmy Button after he arrives in London.]

March 1, 2013

Everything I know about Emily Dickinson I Learned from Lyndall Gordon

Until just a few days ago all I knew about Emily Dickinson was that "hope is the thing with feathers" and she lived (and died) in Massachusetts. (In high school I thought for the longest time that Massachusetts was critical to literary success; it wasn't until we got to Hemingway that we found an American author who was from New England.)

Until just a few days ago all I knew about Emily Dickinson was that "hope is the thing with feathers" and she lived (and died) in Massachusetts. (In high school I thought for the longest time that Massachusetts was critical to literary success; it wasn't until we got to Hemingway that we found an American author who was from New England.)

I've always felt a little bad about knowing so little about such a great poet so when the buzz started about Lyndall Gordon's Lives Like Loaded Guns: Emily Dickinson and Her Family's Feuds, I paid attention. The book went onto my wish list last year and my husband bought it for me for Christmas. I finally started it about a week ago and after some slow going in the beginning, I felt myself get sucked in more and more. By the end I was positively beside myself with who was going to end up controlling her literary legacy and I now feel confident discussing just who Dickinson was and what she accomplished.

Now where is that dreadful American Lit teacher when I need her? I'M READY FOR MY TEST AT LAST!!!

Gordon does an excellent job of using Dickinson's poems and letters (and her family's letters) to buoy her narrative. This bogged me down a bit in the opening chapters as I am not familiar with much of her work so the constant quotes broke up the reading for me. But I understand why Gordon was doing it and I respect that she chose to work this way. She is clearly not just pulling her thoughts out of the air - the biography comes from Dickinson and her family. This is important as a big part of what Gordon does here is [nicely] tear apart the work of others who have written about her subject.

I feel like I should mention spoilers here but since Dickinson has been dead for over a hundred years that seems pretty silly. (So look away if you want to discover her secrets on your own.) Gordon strongly suggests that the poet suffered from epilepsy which makes a lot of sense when you think about her choice (supported by her family) to live a reclusive life. More than that however, the story is about Austin Dickinson (Emily's brother), his first marriage with a woman who was much beloved by the family, and the manner in which he became embroiled in a long term affair with a married woman (sanctioned by her cheating husband). The family dysfunction is EPIC - I can't imagine what their Thanksgiving dinners were like - and had a terrible affect on all of their lives. Ultimately Emily and Austin die, the mistress bonds [for awhile] with the surviving sister and becomes Emily's primary editor (and largely responsible for getting her poems out to the world initially), more havoc is wrought between the sister, Lavinnia, her sister-in-law, the wronged Susan, and the determined mistress, Mabel. The dysfunction moves to the next generation as Susan's only surviving child and Mabel's daughter keep on fighting the fight. In the end it is kind a miracle that Dickinson's original papers survived or that anyone would ever be patient enough to sort through all of this mess and get to the bottom of it.

Three cheers then for Lyndall Gordon!

I learned a lot, I enjoyed what I learned and I really wish that some small part of this story could have been shared with me in high school. It makes me feel a lot more for Emily Dickinson up in her room, stuck putting up with her brother's cheating because he pays the bills that keep a roof over her head (and she can't support herself) (stupid 19th century sexism!), and putting all of her big emotions into her writing. This is really interesting stuff and not to be missed.

[Post pic is the UK edition - love this cover.]

February 25, 2013

Reading/Writing Roundup of Darwin, Barrett, Cook & the Jonathan Livingston Seagull news

1. Prompted by his recent crash, Richard Bach has completed his long intended final part to the bestseller Jonathan Livingston Seagull. I read this ages ago but had no idea there was supposed to be more. I imagine a revised/expanded edition of the classic will be appearing next year.

2. Rebecca Stott* writes in Smithsonian about the impact Darwin's home had on his writing (this is truly a lovely piece) and also in the upcoming issue, William Souder salutes the efforts of Minna Hall and Harriet Hemenway to end the feather trade that was decimating bird species. (There is a fabulous picture book about them, She's Wearing a Dead Bird on her Head!, by Kathryn Lasky; highly recommended.)

3. Everything you ever wanted to know about the seedy Tampa Bay scandal that brought down Gen Petraeus. I have to say, Town & Country is really the best place for this sort of "attempt at climbing the rungs of society" type article. Also, if anyone really doubts why the Kelly sisters were popular with older men after reading this then they are purposely being obtuse. (Pretty flirting women are apparently all the married brass wants.) SIGH.

4. Also, the woman who inspired Hemingway's "Snows of Kilimanjaro". (One of my all time favorites, and clearly a more honest portrayal then one might think.)

What I am reviewing right now:

Six Gun Snow White by Catherynne Valente for my May column. (HOLY CRAP - this was amazing, flat out majestic from start to finish.) (Also best ending ever.) (Also - I have a very skewed perspective on William Randolph Hearst now.) The Lazarus Machine by Paul Crilley for my May column. (Steampunk/Alt Hist coolness, lots of mentions of Ada Lovelace - yea! - two great teen protagonists, several fine female characters, quirkiness all around and more than one killer twist. FLAT OUT FUN.) Tiger Babies Strike Back, for Booklist. (And yes - the cover is certainly demanding a comparison to Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, isn't it?) Infestation by Timothy Bradley for my May column. (Holes meets every "B" monster movie from the 1950s ever made. Tween/young teen boys are going to fly through this one in a matter of hours; it's perfectly crazy and full of smart realistic enjoyable characters.)

What I'm reading now:

Archangel by Andrea Barrett. It's....wonderful. The first story includes Glenn Curtiss' history-making flight in the June Bug and that is only one small part of what makes "The Investigators" one of my favorite reads in ages. If you are a Barrett fan you will be overjoyed with this collection and if you aren't then you are really and truly missing something special.

Also: That Mad Game: Growing Up In a Warzone for my April column (on nonfiction); Imperial Dreams by Tim Gallagher (on tracking the Imperial Woodpecker) for Booklist and the urban fantasy Hidden Things by Doyce Testerman which is proving to be a noir detective/horror/fantasy mash-up in the best possible way. Not sure where a review for this will fit yet, but I'll be talking about it somewhere.

What I'm writing:

I recently had a short personal essay on flying in the Brooks Range accepted by Alaska Magazine, more on that when it runs this fall. I'm working on two separate sections of the western/mountain book - one on Russ Merrill finding a path through the Alaska Range and one on Frederick Cook's ill-fated climb up Mt McKinley. I'm going to try and submit one of these as a standalone to a literary magazine - but no jinxing by divulging too much here :). And finally, I'm writing about the Iditarod Air Force for my new job as a contributor to the Alaska Dispatch Bush Pilot blog. I've had several pieces up there already in the last two weeks including a couple on a recent crash in Rainy Pass.

* I received Stott's book, Darwin's Ghosts, for my birthday, but haven't read it yet.

February 20, 2013

On Frederick Cook & why men climb mountains

I've been thinking a lot lately about Frederick Cook*. In 1906 he claimed to have been the first to summit Mt McKinley and since 1906 a lot of other people have said that he lied. Since what he claimed to accomplish in the time frame he had was pretty much impossible, and since he subsequently lied about getting to the North Pole, Cook has gone down in history as being one of America's most infamous hoaxers. My question is why on earth he risked what was a perfectly respectable exploration career and let it blow up in the craziest way possible.

I've been thinking a lot lately about Frederick Cook*. In 1906 he claimed to have been the first to summit Mt McKinley and since 1906 a lot of other people have said that he lied. Since what he claimed to accomplish in the time frame he had was pretty much impossible, and since he subsequently lied about getting to the North Pole, Cook has gone down in history as being one of America's most infamous hoaxers. My question is why on earth he risked what was a perfectly respectable exploration career and let it blow up in the craziest way possible.

In other words, was saying he reached the summit worth the price he paid?

Cook is a character, in every sense of the word. His feud with Peary (who also stretched the truth about the North Pole) predated their "race" for the Pole (which wasn't really a race but in retrospect seems like one). McKinley was one of the exploration prizes at the turn of the century and has remained so for climbers. (In 1910 the "Sourdough Expedition" reached the North summit, the lower of the two - fueled on coffee and donuts! - but the acknowledged first full ascent of the mountain was in 1912 by the Hudson Stuck party.) Cook's attempt at getting their first, a desperate attempt to be sure, has not been discounted by everyone and there is still a society that supports him, refuting everything that comes out over the years proving him wrong. It's pretty impressive how they have hung in there though, in spite of all the evidence against him. (Which is not helped by the fact that he was later convicted of mail fraud.)

Studying the men who have climbed McKinley makes for fascinating reading. Some did it to be first, some for science (my favorites, really) and some as a sort of spiritual quest. Some are trying, I think, just to "check off the box" - to say they got McKinley just like they got so many others. I don't think there has ever been a "because it is there" nature to mountain climbing (I doubt Mallory even said that about Everest), but there is a need to prove something within the hearts of so many climbers. The ground is not enough for them; they need to reach the top or at least claim that they did. I'll never understand it but trying to make sense of their decisions is fun to think about.

*I'm writing about Cook in my current book. (Because pilots aren't enough, now I need mountain climbers too.)

[More on folks who believe Cook here.]

February 18, 2013

OUT OF TIME by Paula Martinac: It drew me in with the mysterious 1920s photographs; it kept me with the great characters

I bought Paula Martinac's Out of Time at a tiny bookstore in my hometown that went out of business fairly soon after it opened. (Honestly I was not surprised, they had such low stock in there I couldn't figure out why they even bothered to open in the first place.) It caught me with the cover and then the jacket copy about a mysterious scrapbook of 1920s photographs and a potential haunting of the main character was enough to make me buy it immediately. I read it and loved it and every few years I reach for it again. The other day I gave it a reread, largely because I have become so preoccupied with the time period due to my own great grandmother's photographs. It is still wonderfully fabulous and if you can luck into a copy (it's out of print), then I strongly urge you to do so.

I bought Paula Martinac's Out of Time at a tiny bookstore in my hometown that went out of business fairly soon after it opened. (Honestly I was not surprised, they had such low stock in there I couldn't figure out why they even bothered to open in the first place.) It caught me with the cover and then the jacket copy about a mysterious scrapbook of 1920s photographs and a potential haunting of the main character was enough to make me buy it immediately. I read it and loved it and every few years I reach for it again. The other day I gave it a reread, largely because I have become so preoccupied with the time period due to my own great grandmother's photographs. It is still wonderfully fabulous and if you can luck into a copy (it's out of print), then I strongly urge you to do so.

Susan Van Dine is a professional graduate student (lately working on a doctorate to add to her pile of diplomas) who has no idea what she wants to do with her life but keeps hoping to figure it out. In an antique shop she comes across a scrapbook of 1920s photos, all of four young women, and feels powerfully drawn to it. In the days that follow she begins to suspect she is being subtly haunted by one of the young woman - Harriet - and also realizes the women are two couples. With the help of her girlfriend Catherine, a history teacher and researcher, Susan sets out to learn what she can about Harriet, Lucy (who owned the scrapbook) and their friends. The hauntings become much more real and the mystery of what happened to the four women (and how they met and became friends) deepens. In the end Susan finds herself and Lucy and Harriet (and Sarah and Eleanor) and also learns a ton about what it was like to be a lesbian during the Roaring Twenties.

I loved the history (my favorite period really) but it was Sarah and Catherine's relationship that really drew me into this novel. Rather than have Sarah cast aside her girlfriend as she becomes immersed in the mystery, Martinac lets the characters fight their way through this new obsession and work things out. It's what makes the book such a mature read - the characters act like grown-ups which I found quite refreshing.

But mostly - a scrapbook! Photos from the 1920s! Discussion of women's roles in the 1920s! VISITS TO ARCHIVES!

Yeah, you know why I loved it. Perfect winter reading if you dream of finding treasure in antique stores.

February 13, 2013

I'm reading about Emily Dickinson, tiger babies and war. It all makes sense, I swear.

What I'm reading right now:

That Mad Game: Growing Up In A Warzone edited by JL Powers. A collection of essays from conflicts past and present around the world. It's written for teens and will be in my April column. Really interesting stuff - great mix of voices and locations - some are stronger than others but overall it's really a must have for NF collections.

The Inexplicables by Cherie Priest. Finally back to this book! It's another entry in her Clockwork Century series, set in Seattle and focused on three teenage boys and their hunt for something wicked bad in the streets of this near-abandoned, polluted and seriously scary city. Perfect for teens - and yep, I love it.

Hidden Things by Doyce Testerman. This is one of those books that came up in a conversation at ALA Midwinter. I was talking about the new Charles de Lint MG novel, Kate Testerman mentioned he blurbed her husband's recent book, I asked what it was about, she mentioned something about urban fantasy and private detectives and I was gone.

Tiger Babies Strike Back by Kim Wong Keltner. Sort of a tongue-in-cheek revenge against the whole Tiger Mom madness from a year ago with a lot about growing up Chinese American. This one is for Booklist.

Lives Like Loaded Guns: Emily Dickinson and Her Family's Feuds by Lyndall Gordon. Got this one for Xmas and although it's kinda slow for me, I'm digging learning about Dickinson. I know so little about her - I remember learning a few of her poems in school but not much beyond that.

What I'm reviewing:

Yoko Ono: Collector of Skies by Nell Beram and Carolyn Boriss-Krimsky. For my April column and really really amazing. I can't recommend this one enough. Her story is compelling, the design is first class, the photos are great - I love it. It's pretty much pitch perfect.

Also, I'm working on the "Cool Read" for my March column...but not 100% sure on which book that will be yet. (I'm leaning towards this one.)

What I'm writing:

I have joined the staff of the Alaska Dispatch, an online news magazine out of Anchorage. I'm writing AK flying stuff for their Bush Pilot blog. I'm working on a post about a 727 that has been donated to the university aviation program and also looking at some accident data from past years to pick up some trends and pulling some literary references to aviation from AK books. It's a nice gig; we'll see how I do over there as I get more used to writing topical stuff again.

And I'm working on a magazine piece for somewhere else - until it's accepted I don't want to say where (and face humiliation!). I'm also trying to rewrite something that was rejected at one place to submit it to another. And finally for the western book I'm deep in the [mis]adventures of Frederick Cook on Mt Mt McKinley more than 100 years ago. Short story is he said he got to the top of the mountain and he didn't. Or most people know he didn't but some still think it's true. This all fits into the flying stuff too, I swear. Really.

February 11, 2013

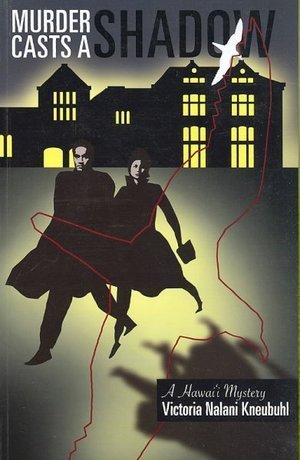

Into 1930s Hawaii with a murder, intrepid girl reporter and a healthy dose of intrigue

Set in 1934 Hawaii, Murder Casts a Shadow by Victoria Nalani Kneubuhl is an enormously enjoyable reading experience. My copy came my way as a Christmas gift and I have to tell you, from the first pages I was gripped by the slow unfolding murder mystery, the rich look at Hawaii's past and the manner in which the author worked history (some of it applies to decades earlier) into the narrative. From the untimely death of a Hawaiian king to the illegal import of Asian antiques to stamp collecting, ranching, Depression-era parties and Gumps (the upscale designer store), this one has a bit of everything. Plus did I mention atmosphere? Holy Hannah - it's got that by the bucketful!

Set in 1934 Hawaii, Murder Casts a Shadow by Victoria Nalani Kneubuhl is an enormously enjoyable reading experience. My copy came my way as a Christmas gift and I have to tell you, from the first pages I was gripped by the slow unfolding murder mystery, the rich look at Hawaii's past and the manner in which the author worked history (some of it applies to decades earlier) into the narrative. From the untimely death of a Hawaiian king to the illegal import of Asian antiques to stamp collecting, ranching, Depression-era parties and Gumps (the upscale designer store), this one has a bit of everything. Plus did I mention atmosphere? Holy Hannah - it's got that by the bucketful!

Mina Beckwith is a freelance reporter in Honolulu who would like a lot more respect and meatier assignments. (Hello Hildy Johnson). Her twin sister Nyla is married to a police detective Todd and his longtime friend, Ned Manusia, is visiting after escorting some historic portraits of Hawaiian royalty back to islands for the British Museum. (Ned is a Samoan playwright raised in London who is "sometimes discreetly employed by a certain agency of the British government"). As the story opens, King Kalakaua's painting is stolen from the Bishop Museum where it was only recently delivered and the curator has been murdered. Mina is hot on the case, she quickly teams up with Ned to follow a clue or two, Todd and Nyla seem to be more involved in the murder than they should be and just when it all looks to be about family greed or deep-seeded local social politics, then nefarious events surrounding the king's very real death in 1891 in San Francisco move to the forefront. That's where Kneubuhl really works her magic by bringing the story of Hawaii's final days as a monarchy into a mystery that seems to not be about that at all and showing how much those tragic events are still about Hawaii, and the people who live there.

Mina is calculated and smart, Ned is thoughtful and measured - and warming to Mina in a very 1934 kind of way - the supporting characters are all quirky and interesting in their own ways which is good as there are a lot of them to keep track of and more than anything, Hawaiian society is about as complex and multi-layered as it gets. The best part is that while there is a wee bit of romantic tension, it's not the point and nobody does anything stupid to propel the plot along (thank you Ms. Kneubuhl!). This is not a modern mystery purposely set in the 1930s or modern characters dropped into a period piece; it all reads very much as a story set in that time and the characters act as they would then.

Murder Casts a Shadow seemed like the best sort of literary throwback to me - a mystery written for a time when you have to figure stuff out slowly and while there are dramatic events (more than one murder occurs), it all serves the narrative and not the author's needs to move things along. I was surprised by the outcome - by the villain especially - and found myself quite sorry to close the final pages. Fortunately there is a sequel and I will be adding that to my Powells list posthaste. Highly recommended.

Find out more on Murder Casts a Shadow over at NPR.