Michael Coorlim's Blog, page 53

October 28, 2013

I’m not homeless, I’m just a writer

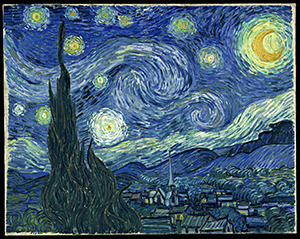

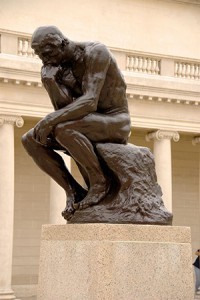

Left: As good as it gets. Right: What you’ll probably get.

As I was walking back from the grocery store, down the sidewalks of Chicago, I drifted out of my usual brainstorm haze with the sudden realization of how I must look to the people I pass along the way.

My hair’s months overdue for a cut, my beard is wild and unmanaged, the cuffs of my jeans sway in tatters around my ankles. My clothes are a size or two too big for me, and I have the disconcerting habit of muttering to myself as I work out bits of dialog or narration, having conversations with people who only exist, as yet, in my head.

Are you leery of me? I’d be leery of me.

As a full-time writer working from home, I spend the bulk of the day in relative isolation, with naught but the cat to keep me company after my girlfriend goes off to work and until she gets back. I do not, as yet, make enough money to support the two of us entirely on my own, and she (the girlfriend, not the cat) is the wonderfully independent sort who would never be content with that sort of arrangement in any event. Even if we had the firm financial state that would allow her to pursue her own artistic goals, they’re the sort of things that would have her out and about the city, acting and taking photographs of things, not hidden away keeping me company.

And that’s fine. I prefer to work in isolation, to secret myself away from the world and lose myself in the creative trance. It’s my drug.

It’s not so much that I’m contemptuous of the social conventions that others expect of me, it’s just that I forget that they exist. I don’t realize how shaggy and uncivilized I look until I see myself reflected in a shop window. If I bother to look, lost in the creative trance as I shamble to and from the store, a distant expression on my face.

It does bother me that my clothes don’t fit, but I’ve lost a lot of weight recently, and I’ve got a bit more to drop before the rate slows to the point where it takes significant effort to lose it. I’m leery of buying new clothes that won’t fit me in a month, so I’m putting that off for now.

Anyway, the truth of the matter is that my job, full-time writer, does not require any sort of actual social interaction. Not at my level of success, anyway. And I’m too close to the margin to feel comfortable not working for significant periods of time, so I tend to turn down social invitations more often than I should.

Full disclosure: I actually was homeless for years.

Not “living under an overpass” homeless, but “couch-surfing and living out of a suitcase” homeless. Between 2007 and 2011 or so I was moving around, state to state, couch to couch, trying to find work and staying with whomever hadn’t quite run out of welcome yet. I’d find work freelancing and, more and more rarely, temping, but a full-time job eluded me.

Still, homeless or not, I was going to interviews, and had to look my best. I had clean, fitting clothes. I shaved before every interview, and got a haircut every few months. Walking down the street on my way to my umpteenth fruitless appointment I’d look like essentially any other commuter.

Giving up on the job hunt and starting my career as a professional author gave me agency over my own life. It was only after I started earning a living wage that I could afford to let go of pretense and become the slovenly writer that was inside, trying to get out. It was only when I could afford to see to my health that I started losing weight, that my clothes became baggy on my frame.

This simply will not do.

Is this an author and his cat, or a homeless guy who’s fallen asleep next to his only friend? Can’t it be both?

As a writer, a purveyor of creative arts, I have a great deal more latitude than those engaged in more traditional employment. This is not license to let myself devolve into a roiling mass of human wreckage. I can blame the insane work schedule I’ve set myself, I can point fingers at the isolating effects of poverty – even if I had the time to go out and be social, I can’t afford to do much my friends are off doing – but in the end I am control of this, in control of my image.

The artist has freedom to look how he wants, dress how he wants, be who he wants, in a way that most professions can’t even conceive of. Is “Distracted Vagrant” my true self?

No.

At least, I hope not.

The post I’m not homeless, I’m just a writer appeared first on Michael Coorlim.

October 25, 2013

And They Called Her Spider, Part 3

This is the continuation of the serialization of the Galvanic Century steampunk mystery novelette, “And They Called Her Spider”. Part 1 can be found here, and Part 2 is here. If you’re impatient like I am, you can download the entire book for free from Amazon.

This is the continuation of the serialization of the Galvanic Century steampunk mystery novelette, “And They Called Her Spider”. Part 1 can be found here, and Part 2 is here. If you’re impatient like I am, you can download the entire book for free from Amazon.

The church the magician had spoken of was in similar condition to the rest of Southwark — old, run down, largely abandoned, and bearing the legacies of multiple fires. Though in heavy disrepair, its structural integrity appeared to have suffered the ravages of time admirably, its steeple bowed and slanted but unbroken, most of the windows in its facade unbroken. A brass placard set next to the chapel doors bore the name “Henry Dobbson, R.G.E.A.”

“He’s Guild, then?” Bartleby asked.

I grunted in reply. It wasn’t exceedingly difficult to proclaim yourself a member of the Royal Guild of Engineers and Artificers, and many second-rate machinists had done so without hesitation. It diffused the actual credit owed those of us who had actually completed the Academy’s rigorous curriculum. There was no real enforcement because no true Guild member had the patience for administrative busywork, and the banking firm we contracted to handle mundane matters for us sold RGEA associate memberships to any dilettante who could afford the hobby and pass a correspondence course.

Bartleby gave the door a quick rap. After a few moments it was opened by an older gentleman, stooped with age.

I immediately revised my opinion of him. His hands, gnarled and callous, were stained with ink and dye. Heavy concentrations of grease had collected under his fingernails, and his glasses were smudged with soot and steam. Distaste and annoyance showed on his face at having to greet potential customers or clients, and his leather apron stank of sulphur and lye. This, gentle readers, was an engineer.

“Mr. Dobbson?” Bartleby asked, covering his nose with his kerchief against the sulfuric odor.

“Did you make greasepaint with mica for the stage magician D’Agostino?” I asked, quick and to the point, before Bartleby started with the small talk. He was my people. I could speak to him.

“What? Yes. I think so. Possibly.” Suspicion crept into his voice. “Why? Who are you?”

“Do you still make it?”

With any luck, he’d think us potential clients and let his guard down. Strangers asking questions were cause for caution. Customers could be safely dealt with and forgotten.

“Only had one man want that slop. Idiot. He insisted on using a white lead base, despite my warnings. The poor girls he coated with it all died of lead poisoning.”

“He didn’t care?” Bartleby asked.

“Men like him never care about what their subordinates go through.”

“Do you have any left?” I asked.

If he hadn’t been making any recently, it was possible that the Spider was one of D’Agostino’s old assistants with a supply of the paint. We’d have to compare samples to be sure, but it was a starting point, at the very least.

“Are you hard of hearing or just simple-minded?” Dobbson asked. “I just told you that it was toxic. Or don’t you care about the poor girl you’ll have wearing it either?”

“It’s not for use,” Bartleby said. “We’re investigating a matter for the police.”

His thin frown vanished. “Well, then, you should have said so. If you’ll follow me.”

Dobbson stepped back, letting us into the old church’s chapel. The pews and other furnishings had been removed, replaced with a number of racks holding commonly available alchemical concoctions for sale. Make-ups, purgatives, abortifacient, exfoliants, analgesics. Along the opposite wall hung a number of sophisticated clocks and novelty clockworks.

“You’re a tinkerer and an apothecary?” Bartleby asked.

“And author, painter, sculptor, and engineer,” Dobbson replied. “The working class likes to keep busy, good sir.”

I chuckled at Bartleby’s discomfort. It was a rare thing to see him unbalanced.

“Wait here. I’ll fetch what’s left of the magician’s greasepaint.”

Bartleby and I busied ourselves looking through the old man’s wares while waiting for his return. Most of the clockworks he had on display were toys and gimmicks — idle fancies that perform no useful functions and serve only to entertain the easily bored. The sort of use of mechanics I despise, so after a brief glance I left Bartleby to it and examined the medicinal goods for sale. Alongside the apothecary staples– the aloe vera, the chamomile, the fennel, the hemp– were substances of more dubious use. Wormwood and aconite, hemlock and nightshade. There were some jars that went unlabelled, and I’m not enough the chemist to hazard at their contents.

“Bartleby?” I asked.

“Mmm?”

“D’Agostino seemed to have an odd reaction to your mention of the Queen. Instant obsequious compliance beyond normal, healthy patriotism. I’ve seemed to notice that quite a bit lately. Is this some sort of recent nationalistic trend I’m unfamiliar with?”

Bartleby gave me an odd gaze. “My friend, you need to step out of your workshop more often.”

Something in his tone compelled me to drop the subject.

First five, and then ten more minutes of idle browsing passed before Bartleby glanced towards me with a questioning look. I nodded, and we left the clockworks and herbs behind, heading to the back of the chapel where Dobbson had disappeared to. There were no other exits, save a ladder heading up into the steeple tower above us. Bartleby stood aside as I began to climb, spanner in hand.

“Dobbson?” I called, ascending into the space above, which apparently served as his bedroom. A simple box mattress sat against the wall, barely leaving enough room for the small wardrobe next to it.

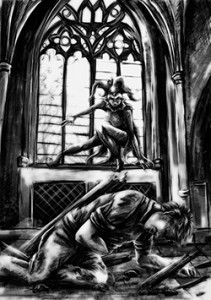

© Collette J Ellis

A streak of red and black fell from the bell tower above before I could climb into the room, breaking my grip on the ladder and sending me crashing down to the chapel below. Sharp knees dug into my abdomen as a rain of powerful fists fell upon my brow, each blow knocking my skull back against the chapel’s wooden floor. I managed to get a forearm up to guard my face in time to see a girl— the Spider, a slight thing dressed in a red and black Jester’s motley— spring back from her kneeling position atop my torso. My face felt raw and numb from her vicious attack, and my lower back screamed as I scrambled back into a half-standing crouch.

The girl’s leap away took her towards the wall beyond the ladder. Her legs folded again as she hit the wall, whatever purchase she managed there sufficing to spring off and away at an angle that carried her past the shocked Bartleby and towards the narrow window. It was thin– too thin for even the slender girl that had attacked me– but somehow she slipped through it effortlessly, and was gone into the night.

Bartleby ran up to me. “Oh god, James, are you alright?”

“Don’t worry about me, go after her!” The fingers I put to my face came away red and sticky. She’d split my lip at the very least, and it felt as though one of my eyes was swelling shut. Thankfully all my teeth were in place, and it didn’t feel like my skull had been cracked.

Self inventory complete, I ran after Bartleby.

***

A few hours later we were back at the church with a small army of Metropolitan Police, searching the place by gaslight.

Inspector Abel approached with a frown. He had been against hiring outside contractors to assist with a police matter, but when the order came down from the Home Office, he’d had no choice but to comply. “No sign of the old man or the girl. We did find, in his apartment, schematics and drawings of the parade route with a number of choke-points indicated.”

“He’s smart,” I begrudgingly allowed. “He’ll have changed his plans.”

“No he won’t,” Bartleby disagreed. “It’s all the spectacle of the thing, yes? Choosing hard targets, dramatic entrances, the attention-getting greasepaint. He knows we have his plans, and he’ll have the girl do her work in spite of us. Imagine the publicity he’ll garner if he pulls it off.”

“I didn’t think engineers cared about that sort of thing,” Inspector Abel said.

“We don’t,” I replied.

“He won’t pull it off.” The Inspector was adamant. “If you don’t manage to catch him, my boys will stop this Spider of his in the act.”

Bartleby and I glanced at one another, not sharing his enthusiasm.

***

The Home Office didn’t appear to, either. The next day we were called into a meeting with the Home Secretary, Herbert Gladstone.

“The Queen’s Jubilee is rapidly approaching, gentlemen. The spectacle is vital to the mental and economic health of this Empire.”

“More so than Her Majesty’s life?” Bartleby asked.

Gladstone’s face darkened. “Cancelling the parade is an admission of weakness, of fear, something I cannot tolerate even if the Queen were to allow such a craven response.”

“Seeing the monarch gutted on a parade float would be a good deal worse for morale, I’d imagine,” I said.

Gladstone and Bartleby stared at me in abject horror before doing the respectable thing and pretending I’d never said it.

“It is imperative that the two of you catch this Spider before the parade.” Gladstone set a doll atop the desk. Garbed in red and black with a porcelain face it was the very image of the assassin.

“What’s this?” Bartleby asked.

“Blast if I know. The Scotland Yard found it in the church after you two departed for the evening. It’s some sort of clockwork– see if it gives you some insight into the killer.”

To be continued next Friday

The post And They Called Her Spider, Part 3 appeared first on Michael Coorlim.

October 22, 2013

Orphiction

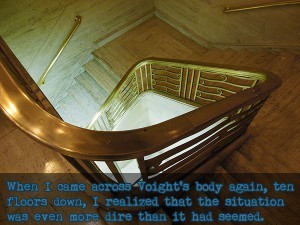

Orphiction (A portmanteau of “orphic fiction”) is simple project in which I take random free stock photos from sites like morguefile and come up with short microfiction to suit them.

It’s very much an experimental process for me, but the individual pieces are fun to do. I sift through stock photo galleries until something grabs me in just the right way. Sometimes the text comes quickly, other times I need to roll it around in my head for a bit until all the rough corners are worn away.

It’s very much an experimental process for me, but the individual pieces are fun to do. I sift through stock photo galleries until something grabs me in just the right way. Sometimes the text comes quickly, other times I need to roll it around in my head for a bit until all the rough corners are worn away.

I think it’s interesting, at the very least.

I’m not even sure what to call this, really. Webcomic? Microfiction? Whatever it is, it updates three days a week, and I’ve got posts scheduled into the new year.

The post Orphiction appeared first on Michael Coorlim.

October 18, 2013

And They Called Her Spider, part 2

This is the continuation of the serialization of the Galvanic Century steampunk mystery novelette, “And They Called Her Spider”. Part 1 can be found here. If you’re impatient like I am, you can download the entire book for free from Amazon.

This is the continuation of the serialization of the Galvanic Century steampunk mystery novelette, “And They Called Her Spider”. Part 1 can be found here. If you’re impatient like I am, you can download the entire book for free from Amazon.

I am not a fan of opera, nor any passive entertainment, really. It isn’t so much that I am incapable of grasping them as Bartleby has on occasion implied, but when I’m not working (and, as Bartleby will tell anyone shortly after meeting them, I am almost always working) I prefer a good earthy carouse to sitting in some stuffy theatre, watching painted men prance around like women, and listening to songs I cannot begin to understand the lyrics to. I like things simple. I like things precise. Efficient. Art is none of those things, and I daresay I’ll never understand it.

Still, through my association with my partner I am not entirely ignorant of the venues the city offers to patrons of the arts, and I was thus surprised when Bartleby didn’t lead me to the Royal Opera House. He didn’t lead the way to the recently opened London Coliseum, or Sadler’s. He instead traveled down a maze of side-streets and walkways, past pawn shops and brothels, almost beyond the outskirts of the city to what looked like a ramshackle warehouse worn by years of neglect.

“This can’t be right,” I said.

Bartleby simply smirked, gesturing towards a hand painted sign declaring that yes, Il filosofo di campagna was to be performed that evening, and swept through the front doors. The interior was in scarcely better condition than the exterior, dark curtains placed over cracks and gaps in the walls, paint and graffiti splattered over the plywood that seemed to be holding everything together. A small crowd of what I presumed were actors and crew hustled about, completing whatever construction they hoped would make the place suitable.

“It looks as though they’re still building the theatre,” I said.

“They are,” Bartleby said. “You laugh, but I’m quite serious. This is an unlicensed troupe — they stay on the move, performing at a new, temporary venue every other night to avoid the scrutiny of the police.”

“What’s their company name?”

“They don’t have one.”

“I had no idea that such a thing existed.”

“Oh, yes. Underground artistic endeavours are always the rage, don’t you know? Of course, much of what they perform might be labelled as subversive by the small of mind or quick to judge. Plays about Fawkes, female performers, abolitionist manifestos, that sort of thing.”

I chuckled. “You’ve got me associating with agitators and anarchists now? What’s next, Luddites?”

“Oh, only the most talented, I assure you.”

He made his way across the floor towards a young woman dressed in men’s clothing, applying makeup to a young man dressed in women’s clothing. Theatre people.

“Lilly, can you spare a moment?”

“Oh.” The woman didn’t look away from the eye shadow she was applying. “Hello, Bartleby.”

The young man she was making up was dressed as something naggingly familiar — possibly some popular literary figure I wasn’t fully remembering.

“I’ve got something I’d like you to take a look at,” Bartleby said.

“If it’s your John Thomas again I’m not interested.”

Knowing my partner, I honestly wasn’t shocked. And that disturbed me.

Bartleby handed over a swab containing a bit of what I recognised as the greasepaint the police’s evidence had provided us with. The girl took a quick glance at it, then grunted and slipped a wig onto her actor.

With a cold shock I realised that she’d been making him up to look like Queen Victoria.

“Bartleby—” I hissed, gesturing at the man-woman.

“Yes? Oh. They’re doing some show for the Jubilee.”

“Sail’n along the parade route the night before,” the actor playing the Queen said. “The band will be play’n, and I’ll be wav’n.”

The girl had pulled out a jeweller’s loupe to examine the swab that Bartleby had given her. “It’s got bits of mica in the oil. See that slight sparkle? Definitely flashier than a base you’d use as a foundation. And look at how bright the white is — any of my actors in this would be a huge distraction.”

“Just as I had thought,” Bartleby said. “Thank you for the confirmation. Do you know who makes it?”

She shook her head. “Nothing commonly available. I used to work with a stage magician who’d use something like this on his assistants. You should have seen the way they sparkled under the house lights.”

“A stage magician! How perfectly splendid. You wouldn’t happen to know where I could find him, perchance?”

***

Bartleby had once admitted to me a flirtation with opiates in his naval days. He seems the type, at first blush, to be drawn into the languid purgatory of opium addiction, but as any sensible man knows first impressions can be deceiving. It isn’t pleasure that my partner is addicted to, but experience. The new and the novel, the strange and sublime. He confided in me that he knew almost immediately that he could not persist with his opium experimentation — if he had, he wouldn’t have wanted anything else, and to a man like Bartleby such artificial contentment is the world’s greatest prison.

Each opium den we visited in our search for the magician D’Agostino was more wretched and pathetic than the last. Old men and young, the poor and affluent of all races and nationalities lay insensate and uncaring, heedless of the amazements of this age of wonder we live in. I often wonder what it could be that makes the simple experience of living life so unpalatable to so many, that they’d rather lose themselves in such a numb escapism. The attendants of the dens, while initially taciturn and tight-lipped, were all too eager to help once Bartleby had given them a few coins.

The stage magician looked like many of the other addicts, an older man in faded clothes, leaning against a wall, slack jawed with vacant eyes, cracked lips loosely held a pipe trailing thin wisps of smoke into the air. He was utterly unresponsive to Bartleby’s initial attempts to rally his attention, and didn’t so much as glance our way until I gave him a good hard shake.

“D’Agostino?” The waste and excess had put me into a foul mood. “You! Are you the magician D’Agostino?”

He muttered something that I didn’t quite catch.

“What?”

“Illusionist!” His weak arms tried to push me away as he slumped to the side. “Prestidigitator! Never magician.”

Pity and revulsion warred within me, pity winning by the narrowest of margins. We weren’t going to be getting any useful information out of the wretch in this state. I stood, still holding him, lifting the slack form of the illusionist to dangle by the waistband of his trousers.

Bartleby turned to the den’s attendant with an embarrassed chuckle. “We’ll… uh, we’ll be taking him home with us.”

***

Recovering from opiate addiction is a slow and painful ordeal. The body grows dependent on the drug to function, and when deprived it reacts like a spoilt child throwing a fit. The detoxification process naturally takes up to a week, and we did not have the luxury of time on our side. Fortunately, after hearing about Bartleby’s experimentation with the drug, I resolved that if he ever should succumb I should help him recover — and to that end I had built a detoxification apparatus.

“I really don’t think that this is entirely necessary.” If I didn’t know better I’d have said that Bartleby actually sounded concerned about the old addict. “We can simply sober him up and question him later.”

“Nonsense,” I said. “Look at this poor wreck of man. We would be remiss in our social obligations if we didn’t do all in our power to cure him of the drug’s grip.”

Besides, I hadn’t been able to test the Detoxification Apparatus, and if there’s one thing an engineer understands, it’s how to take advantage of the opportunities that providence affords.

“Help me strap him in.”

The Apparatus took the form of a sturdy wooden chair reinforced with tin plates, having manacles and ankle cuffs built into its arms and front legs. A brass casing had been built into the back, holding an array of syringes set into a clockwork gatling cycle, along with a pair of small phonographs reading from the same wax cylinder mounted at the base. D’Agostino looked barely cognisant of where he was, and didn’t react when I snapped the supportive brace around his neck.

“Is that really necessary?”

“Oh absolutely. We don’t want him thrashing around and injuring himself or dislodging the needles.” While I may not like it when others watch me work, I do so enjoy explaining the operation of my inventions to an audience.

“Thrashing?”

“There will be a significant amount of thrashing, Bartleby. The Apparatus is going to syphon out, filter, and recycle his blood and spinal fluids. I imagine that it is going to be quite unpleasant. I’m going to numb his brain’s pain receptors, but that’s still a goodly amount of needles.”

“That sounds absolutely horrid.”

“Oh my yes.” I began winding the crank that would regulate the needles’ movement. “But I’m no monster, Bartleby. See the twin phonograph horns? I should say some Strauss will help keep our ‘illusionist’ calm during the procedure.”

I stood, clapping the dust off of my hands and we left my workshop up the stairs to the ground floor. Down below we could hear the first strains of The Blue Danube beginning.

***

D’Agostino was alert and awake when we returned in twelve hours to unstrapped him, cleaned him up, and gave him a nice hot bowl of pea soup.

“You monsters!” he said by way of thanks for the new chance at an honest man’s life I’d provided him with. “You lashed me down and left me for hours in that infernal torture device!”

“So you would characterise the experience as entirely unpleasant?” I frowned in disappointment. I had really expected that the music would have alleviated the stress of going through a week’s detoxification in less than a day. Perhaps if I developed a system to automatically switch cylinders when one song ended? “Yes, I imagine that nine hours of any one song could grow tedious.”

“Unpleasant? You tortured me. I’ll have the Met on you! They’ll have you swing in Newgate!”

“They tore Newgate down,” Bartleby informed the magician. “But if it is any consolation, you needn’t go far to report us. We’re currently consulting for Scotland Yard.”

D’Agostino grew very silent and still as he let that sink in. “Oh. I… I see.”

“Yes, so you’d better tell us what we want to know—”

Bartleby was quick to cut me off. “Mr. D’Agostino, we’re working on a very important case for the Home Office, and we believe that you might be able to assist us in an informative capacity. The matter relates directly to the upcoming Platinum Jubilee. You do love your Queen, don’t you?”

“I love the Queen.” His response was quick and almost automatic, in the way that many had adopted since the turn of the century.

“Then you’ll help us, won’t you? Help us help Her Majesty?” Bartleby asked.

He nodded with hesitation, not making eye contact with either of us.

Bartleby slid the swatch of greasepaint across the table towards the illusionist. “This substance is related to a person of interest we’re investigating, and we understand you used to use a similar foundation in your stage shows?”

He examined it carefully, tilting the swath so that the mica glittered in the dim lights of my workroom. “Oh, something similar, yes. For misdirection’s sake — the more eye-catching my lovely assistants, the less focused the audience was on what my hands were up to.”

“And that lack of scrutiny made performing your tricks easier?” I asked.

“They were no mere tricks,” he said. “I performed illusions.”

“Why did you stop?”

“The winds shifted. Audiences dwindled. I couldn’t keep up anymore — the illusions the younger generation could perform with the wonders of modern technology far outshone my repertoire — and I was too old and set in my ways to adapt.”

“Did you make the paint yourself?” Bartleby asked.

“Me? No. Such alchemy is beyond my purview, I’m afraid. I special ordered it from an apothecary down in Southwark.”

“Do you remember the address?”

“No, not off of the top of my head — this was years ago.” D’Agostino shook his head. “I do remember that he operated out of an old church — it shouldn’t be terribly hard to find.”

To be continued next Friday.

The post And They Called Her Spider, part 2 appeared first on Michael Coorlim.

October 17, 2013

Art, Creativity, and Ideas

Art is one of those topics that can be difficult to discuss, simply by virtue of having no single objective definition. The entire philosophical field of aesthetics is built around the quest to define art, and yet it’s something that surrounds our lives, our world, and our culture. Of course, we talk about it, we discuss it, we debate it. A precursor to that conversation is not only understanding what you mean when you say ‘art’, but what those who you’re talking to hear when you say the word.

Art is one of those topics that can be difficult to discuss, simply by virtue of having no single objective definition. The entire philosophical field of aesthetics is built around the quest to define art, and yet it’s something that surrounds our lives, our world, and our culture. Of course, we talk about it, we discuss it, we debate it. A precursor to that conversation is not only understanding what you mean when you say ‘art’, but what those who you’re talking to hear when you say the word.

Art is the derivation of meaning from synthesis

At least, that’s what I’m talking about when I say ‘art’. Let me break down what that means, in reverse order.

Meaning from synthesis

The human brain excels at one thing: patterns. What we view as intelligence is really nothing more than analyzing and drawing connections between disparate bits of information. The better your brain is at drawing these connections, the faster it is, the more intelligent you appear to be. You might be able to draw connections between social behavior and intent, and thus be emotionally/socially intelligent, or you might do better in the abstract with mathematics.

The human brain excels at one thing: patterns. What we view as intelligence is really nothing more than analyzing and drawing connections between disparate bits of information. The better your brain is at drawing these connections, the faster it is, the more intelligent you appear to be. You might be able to draw connections between social behavior and intent, and thus be emotionally/socially intelligent, or you might do better in the abstract with mathematics.

The human mind is so adept at drawing connections and discovering patterns that in extreme cases it can lead to cognitive bias, where we create spurious connections because that is what we notice; our minds filter for what data fits our preconceived notions. This is what lies behind Discordianism’s rule of 5s, as expanded upon by Robert Anton Wilson in Cosmic Trigger.

At the other extreme you have a state similar to enlightenment or the Taoist Wu Wei; when you are in harmony with the universe you’ll see the patterns you need to in everything and act without thought or hesitation. This is also what we call instinct – when we stop over-intellectualizing our thought process and let the subconscious point out these patterns to us in its own way through synchronicity and dream.

Creative intelligence is the process of forming new patterns between elements that aren’t already connected. This is what we call a ‘new’ idea – the fusion of two old ideas. This is where artists – writers, illustrators, filmmakers, whatever – get their ideas: combining old things… books they’ve read, movies they’ve seen, conversations, dreams, stray thoughts… in new ways.

This is not, however, art.

Derivation of Meaning

Without an intelligent mind to draw connections and derive meaning from a physical object, that object is contextually inert. It has no meaning. A painting is oil on canvas. A sculpture is clay. A story is ink on wood pulp. A song is vibrations in the air. On your computer, all of these are just arrangements of bits in the ‘on’ and ‘off’ position. It’s only when a thinking observer engages with the piece and draws some sort of connection that it has the potential to become art. Simply being created is itself not enough.

Without an intelligent mind to draw connections and derive meaning from a physical object, that object is contextually inert. It has no meaning. A painting is oil on canvas. A sculpture is clay. A story is ink on wood pulp. A song is vibrations in the air. On your computer, all of these are just arrangements of bits in the ‘on’ and ‘off’ position. It’s only when a thinking observer engages with the piece and draws some sort of connection that it has the potential to become art. Simply being created is itself not enough.

Artists do not create art. They create the potential for art. They create a catalyst. The meaning is imposed by the viewer/reader/listener, who draws connections between what they’re experiencing and what they’ve encountered in the past.

What about authorial intent? Well, the author experiences his art, too. The actor is witness to his own performance, though in a different manner than the audience. The process of writing a story, watching it evolve, that’s art too, if the writer deems it such. We do not, however, create meaning for the audience; we create something we hope they will fit into one of their own aesthetic patterns.

That’s what I do. I write, I create, I give you something to envision, but I am by far the least important part of this process.

The post Art, Creativity, and Ideas appeared first on Michael Coorlim.

October 11, 2013

And They Called Her Spider, part 1

For the next month or so I will be serializing “And They Called Her Spider,” the first novelette in the Galvanic Century series of steampunk mysteries. If you’re impatient like I am, you can download the entire book for free from Amazon. It was a stylistic choice to use British spellings in these stories.

For the next month or so I will be serializing “And They Called Her Spider,” the first novelette in the Galvanic Century series of steampunk mysteries. If you’re impatient like I am, you can download the entire book for free from Amazon. It was a stylistic choice to use British spellings in these stories.

“She moves, at times, with the fluid grace particular to acrobats and dancers, and at others her motions are sudden and jerky, feral and darting. A birdlike tilt of the head, an abrupt twist of the spine; that’s all the warning given before she changes, transforming from entertainer to killer, from elegant to lethal. My pet theory is that when she becomes the perfect assassin she gains a new awareness of time and kinetics, her movements so graceful and quick that the human mind can only process them in sudden still images, like the frames of a zoetrope. Mere words can barely suffice to convey the purity of her motion. I have to think of her in alchemical terms. She’s quicksilver.”

Bartleby strode the perimeter of my workshop as he spoke, quartz knob on the end of his walking stick clacking a steady metronome beat against brass fittings set into the walls. He did it to irritate me, of that I’m sure; both the tapping and the purple-prose drenched answer to the simple question I’d put to him.

“That’s all well and good. But who is she?” I asked.

He turned away, cane rattling along the baluster of the staircase leading up to the rest of our townhouse. “I swear, James, if you’d spend less time down here and more at the club with me, you’d know what was going on in London. The social season doesn’t last forever, you know, and people find you odd enough as it is.”

“I’ve little regard for the opinions of toffs or the clubs they inhabit.”

“But they’re so useful, James!”

“Then save your patter for the swells. Just tell me who this ‘Spider’ woman is.”

“Nobody knows, and that’s the thrill of it. She comes out of nowhere, a flash of red and black fabric, powdered white face, the tinkling of bells, drawing near in that sinuous way she has, mesmerising and captivating even those with the presence of mind to recognise her as a threat. What else is one to do but watch when presented with a beautiful spectre of death? When I saw her, at first it was the sheer oddness of the sight that stayed my hand: a small girl, slender of frame and fine of feature, dressed as a jester. She entered the airship impossibly, through a port window a thousand feet up—”

“A thousand? Airships cruise at four or five-hundred, maximum.”

“—a thousand feet up, to dance and pirouette through the crowd with precision and aplomb, and then someone was dead.”

“So what you’re saying is that this woman killed someone while you stood and stared, slack jawed?”

I hefted a long slender blade, a weapon purported to belong to the assassin herself. It — along with the rest of the artifacts littering my workbench — made up the sum product of Scotland Yard’s investigations thus far. With the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee but days away, they’d resorted to commissioning our services as consulting detectives. There were older agencies, larger ones, and many with a better reputation, but Bartleby and I had some small name for handling the more outlandish and sensitive matters.

“That’s not what I’m saying at all,” Bartleby stopped, settling into a relaxed stance. “She danced, and then the American industrialist sponsoring the gallery flight was dead. I was watching… we were all watching her, but she barely approached the man. She went from her smooth acrobatic dancing to a jerkier sort of movement. She… I swear… seemed to flicker for a moment, and her target collapsed.”

“You didn’t actually see her cut him.”

“Nobody did. Just like her prior victim and the ones before that. When we landed the airfield physician gave the same diagnosis — poor bastard had been neatly eviscerated.”

I later learnt that it had been the cleanliness of her cuts that had given cause to the broadsheet’s efforts to link her to the Ripper, one even going so far as to label her “Jack’s Daughter” before some other publication started calling her “The Spider.” Lord only knew why that name stuck when the half-dozen others put forth fell by the wayside.

“I’m honestly just grateful for the opportunity to have seen her in the flesh,” Bartleby said. He ran his delicate hands over the rest of the evidence the Met had given us: shattered glass, scraps of fabric, a smear of greasepaint from a curtain she’d brushed against. While ignorant eyes might have seen nothing but bored fiddling in his actions, I knew Alton Bartleby well enough to know that his mind was working, collating the data it perceived, categorising it and making inexorable progress towards an inevitable solution. His method was as singular as the Old Man’s, retired these last six years, but came from a different genesis.

Bartleby was a true savant, and while the Great Detective had always made his deductions look easy and natural, in my partner’s case they truly were. Building conclusions from disparate scraps of data was easy for him as deciding what to have for lunch would be for you and me.

Deciding what to have for lunch — now that he found challenging.

“And if enchantment she wove, then the death she delivered was the key to breaking it. Not that it mattered. In the chaos that followed she escaped, somersaulting through the doors from gallery to galley, and from there? God only knows. Back out the window, perhaps; gone before a single hand could be raised against her.”

For six months, the Spider had been the terror and scourge of London, an assassin without equal, a perfect murderess against whom no precaution was adequate. None could speculate at what hand it was that moved her across the board, and she seemed to strike out without prejudice against all targets, her daggers finding ready homes in the innards of Anglican bishops, Turkish ambassadors, union agitators, French statesmen, Royal Academy lecturers, and visiting American plutocrats alike. The only thread weaving together her web of victims was the exemplary security with which they protected themselves; her partners in this danse macabre were the men no other killer could reach.

“You’re fond of her enough,” I said.

“She’s news. She’s scandal. She’s morbid entertainment for peerage and hoi polloi alike, a penny dreadful come to wicked life. I’m honestly surprised that you haven’t heard of her before now, James.”

“You know how it is,” I replied. “When I’m working the rest of the world fades into an annoying niggle which I can safely ignore.”

“That hardly sounds healthy.”

“The isolation helps me think.”

Truth be told, while I don’t care for most people I didn’t even like Bartleby coming down into my workshop. He felt wrong there, out of place, a grain of sand in my oyster; company in my working place was always an intrusion. He knew it, and most of the time respected it, sending down meals in the dumbwaiter, or calling from the top of the stairs if matters were important. This was perhaps the third time he’d been down in my workshop. It probably wasn’t quite fair, considering that his wealth had paid for it.

In this social regard Bartleby was my opposite. While I preferred the isolation of what he had playfully but accurately termed my “lair,” he was a social animal, flitting about the London scene like a hummingbird, supping at the nectars high society had to offer. A gentleman forever on the cusp of the latest fashions and trends, of means, with an addictive personality and too much free time, he had fallen in love with the idea of the Spider from the moment he first saw her lithograph.

He eagerly purchased any publication that so much as hinted her, dined and interrogated any that claimed to have witnessed her murderous performances, and had waxed melancholic at his own ill-fortune in not having seen her himself, until that fateful airship voyage. His obsession did not go unnoticed, and the expertise my dilettante partner’s obsession had acquired lead directly to the Home Office calling on us.

Bartleby was in heaven. Even to those with connections as influential as his, the evidence lockers at Scotland Yard were off-limits, and the crumbs available at auction were only those artifacts that the Met didn’t feel were relevant to their investigation. As proud of it as he was, Bartleby’s collection of Spider memorabilia had been somewhat on the paltry side, things of value and interest only to the morbidly obsessed… but creative sorts live and thrive on just that sort of obsession.

A fact I understood all too well, so I refrained from needling Bartleby about it.

Too much.

The evidence the police had transported to us, on the other hand, held treasures that Bartleby could have only dreamed of. Recovered murder weapons. Shards of glass from her more explosive entrances, mixed in with possible fibres from her costume. A bit of lipstick scavenged from the cheek of a victim she’d pecked while driving a dagger into his sternum. All of it tagged, logged, labelled, and displayed, laid out in my workshop.

Bartleby abruptly rose and began to ascend the steps, seemingly having lost interest in the artifacts. I turned from the table to watch him go, befuddled at his abrupt change in demeanour before realising that he’d come to some sudden conclusion about the case.

“Lunch then?” he asked.

“Any conclusions?” I asked.

He ignored my question until we were in the entrance hall at the top of the stairs. I’d insisted upon my workshop entirely cut off from the rest of the basement, the kitchen and the servants quarters. It wasn’t that I didn’t like or trust them — I came from a working class upbringing myself. While I find our servants less tiresome than Bartleby’s peers, I do not much care for any company when I’m working, and Bartleby calls such fraternisation with those he deems my lesser unseemly.

“I’ve concluded that I’m in the mood for a light fruit compote for lunch,” Bartleby said. “What shall I have Mrs Hoddie fix you?”

“Bread with drippings,” I said. “No, Bartleby, conclusions about the Spider. You’ve worked something out?”

“What I cannot work out is your taste for bread soaked in last night’s dinner. I’m rather well off, you know. You needn’t eat like an east end factory worker.”

“It was how I was raised,” I said.

I have little patience for small talk. It isn’t my way. I had grown up in a working class family, raised by a father with little tolerance for idleness or affection for his children, and I preferred conversation be short and to the point. Bartleby knew this, of course, and his continued deflections were his attempt to rile my temper for his own amusement. I would not give him the satisfaction.

Still, I had to wait with growing impatience and discomfort while the cook prepared Bartleby’s compote, and again while he took his goodly time nibbling at it. It was a good ten minutes of idle chatter concerning matters of little interest until he placed his napkin to the side of his plate and abandoned the facade of disinterest that he wore so very well.

“I say, do you know what I fancy, James?”

“You fancy any number of terrible things.” Out with it, already.

“I fancy some entertainment. Do you care to take in a show?”

“Is this related to the case we’ve taken or have you just gotten distracted again?”

He ignored my hostility. “Perhaps an Italian opera. Something jocular. Some sort of dramma giocoso — yes. How about Il filosofo di campagna?”

“On with it, Bartleby.”

“Oh, I think you’ll like it. It’s no opera buffo, but your working-class sensibilities will enjoy the intermezzi at the very least.”

I glared at him while the housemaid cleared our dishes away, but he seemed impervious to my sincere desire to throttle him with my mind.

The post And They Called Her Spider, part 1 appeared first on Michael Coorlim.

October 10, 2013

Fallen London is a Delicious Time Waster

As a writer I am prone to procrastination. I binge on it. I install a game or Netflix a series, watch/play it for days during which I get nothing done, and then get sick of it and get back to work. It’s not that I’m undisciplined; I just know how these miniature obsessions work. As soon as I understand something well enough to render its base elements — figure out the perfect economic strategy in a simulation game, or figure out the formula in a show to predictive levels, I tire of it and move on.

As a writer I am prone to procrastination. I binge on it. I install a game or Netflix a series, watch/play it for days during which I get nothing done, and then get sick of it and get back to work. It’s not that I’m undisciplined; I just know how these miniature obsessions work. As soon as I understand something well enough to render its base elements — figure out the perfect economic strategy in a simulation game, or figure out the formula in a show to predictive levels, I tire of it and move on.

My latest interest is a browser-game called Fallen London.

Fallen London by Failbetter Games

Fallen London is a story-based browser game by Failbetter Games with a Gothic Victorian fantasy theme. It plays out a bit like a board or card game; you draw story cards, playing them as you see fit. Each card has a bit of evocative prose, and one or more options to choose from, each of which has different potential effects. There are definite RPG elements involved, as your choices will both change your character growth and guide what cards and options are available to you in the future. Cards themselves (called storylets) (as well as the options they offer) are acquired based on your character statistics, your in-game location, and which in-game flags you’ve triggered.

What Makes Fallen London Addictive

Despite acquiring the same cards again and again, there’s not a strong repetitive feeling to playing Fallen London. You definitely feel a sense of progression, not only as your stats improve, but as you move along different plot-lines. The primary reward for these cards is more bits of the narrative… setting detail parceled out in exquisite chunks of well-written prose. This strongly appeals to the writer in me.

In fact, so appealing to it is that while there is an optional real-money marketplace (you buy a resource called Nex), according to the company blogs on the subject the primary purchase isn’t more turns to play, but rather exclusive story options and directions. Quest lines that are not normally available in other ways.

What Makes Fallen London Dangerous

Fallen London is one of those browser-based games where you have a limited bank of turns, and these turns regenerate one every ten minutes. Unless you pay the fee ($5/month) for the upgrade, you cap at ten turns. These turns go quick, but ten minutes passes by quickly.

My original intent was to incorporate playing with the pomodoro time management scheme I use. Write for 25 minutes, take a five-minute break to play my two turns, then back to work. In practice, though, I find myself taking a turn, checking my email, message boards, twitter, etc for ten minutes, then taking another turn.

Again and again.

This is, obviously, a problem, because I’m not sick of the game yet, and I have Dreams of the Damned revisions to finish if I want to get the book out by the end of the month. I’m working on coming up with a system that lets me get the work done that I need.

Come. Play.

Interested in giving the game a shot! Cool. Do me a solid and sign up through my profile. I get bonus turns when you do.

Or better yet, don’t. Go to the game’s page and sign up there. I really should be working.

The post Fallen London is a Delicious Time Waster appeared first on Michael Coorlim.

October 9, 2013

Writing Beyond Books

I have aspirations, man. Lots of them.

I write.

It’s not just what I do. At this point, it’s so integrated into my life that it’s become part of who I am. Guy-Who-Writes is the core of my identity. Not only is it what I do for a living, but to be honest a lot of the time it’s all I want to do. I don’t really mind the rest of what goes into the publication process… revisions and cover design and layout and whatever… but I’d rather be writing. And I’d rather be doing the other publishing stuff than going shopping or watching television or eating or sleeping.

Funny how your dream job can turn you into a workaholic.

I write books.

For the last year-and-a-half or so I’ve been writing prose. Steampunk mystery and thriller novelettes and novellas, for the most part, though I recently produced a collection of five psychological apocalyptic stories modeled after the stages of grief. I’m going to be writing a lot more books of all sorts. It’s how I earn my living. Not a great living, but people seem to like my work well enough that I don’t need to scrounge for temp jobs or do freelance copywriting these days.

I wrote a web series.

No, you haven’t seen it. Very few outside the cast and crew have seen the pilot.

It’s a surreal atmospheric horror found-footage project similar in ways to Marble Hornets or Louise is Missing, though perhaps closer to the latter and not as overtly supernatural. It’s cool and creepy and funny and the actors are absolutely fabulous. It’s also currently in development limbo, as our production company had to pull out, citing financial difficulties. We’ve got two seasons scripted. I’m shopping it around.

I’d like to do more screenwriting, either for indie film and web-series or television. I particularly enjoyed the casting process.

I drew comics.

I used to draw as much as I write, back in the day. In high-school I’d fill notebooks up with comics drawn to amuse myself and my friends, bizarre absurdist scrawlings drawing from the people we knew, pop culture, and the comic books I studied to learn how to do what they were doing.

I don’t draw any more. I wasn’t really any good at it. I’d still like to take part in the production of comics as a writer, either on a small project or on a freelance basis for a company.

I make games.

Another hobby that I don’t have any time for anymore is game development. Coding appealed to the structuralist in me, solving problems, coming up with systems that emulate what you need them to.I even finished a few text adventure games that are, perhaps mercifully, lost to the the annals of time.

What held me back was, again, being a one-man show with abysmal graphic design skills. I absolutely would not mind working in game development as a writer or level designer, though.

The post Writing Beyond Books appeared first on Michael Coorlim.

October 8, 2013

Random Title Generator

About a year ago I wrote a random title generator to help myself learn HTML5 and javascript. It’s simple enough in execution; press a button and get five random titles to draw inspiration from.

Sample Output

Dancing Pirate In Lead Ticket

The Automatic Avenger

The Avenger of the Farm House

The Key that Died in the Carnival

The Invisible Cotswold

The results aren’t always terribly sensible and sometimes you might need to tweak what you get — “Dancing Pirate In Lead Ticket” becomes “Dancing Pirate with a Lead Ticket” — but they’re often inspiring, or at least amusing.

How it Works

Basically I took a bunch of old pulp magazines and short fiction anthologies and harvested the different words from them – nouns, verbs, prepositions, adjectives, adverbs – and built javascript arrays out of them. I also created a set of title structures that draws the parts of speech from these arrays. When you click the button, it picks a random structure and then plugs the linked parts of speech into it.

So, "The " + noun + "'s " + noun becomes “The Island’s Mistletoe”

Yeah, my girlfriend thinks I’m a nerd, too.

Further Development

I’m working on version 2.0 now, with a new collection of source titles and a filter for different genres. This takes a lot of time, though, and I suspect it’d be better spent writing, so don’t expect anything anytime too soon.

The post Random Title Generator appeared first on Michael Coorlim.

October 7, 2013

Repurposing Old RPG Materials

Tabletop Role-Playing Games were one of my primary hobbies growing up. Once a week or so, my friends and I would get together in someone’s basement to roll dice, talk in funny voices, and commit imaginary mayhem on imaginary antagonists. I was the only one consistently good to go with an adventure every week, so it usually fell to me to run the game and present a compelling story to my players.

Tabletop Role-Playing Games were one of my primary hobbies growing up. Once a week or so, my friends and I would get together in someone’s basement to roll dice, talk in funny voices, and commit imaginary mayhem on imaginary antagonists. I was the only one consistently good to go with an adventure every week, so it usually fell to me to run the game and present a compelling story to my players.

I didn’t mind, though. I loved it. I wrote a little, but it wasn’t anything serious, and coming up with adventures and campaigns was my primary creative output. I also accumulated a number of canned “ready made” rpg adventures, but that was more of a collecting thing… by far I preferred to come up with original scenarios for my friends.

I still play from time to time these days, though I’ll freely admit it’s almost entirely play-by-post games online. It’s hard to get dedicated face-time with people who have careers, families, and other interests competing with their time. My own creative energies these days are poured into my writing, so I no longer have the luxury of spending five days preparing a game for the weekend.

Finding use for those old adventures

These days what I’ll do is take one of the old adventures that I have — either some of the old material I used to run, or one of those ancient published adventure scenarios. Some of these old games are fairly well known, though, and the last thing I want is a player recognizing some aspect of the game, digging out their own copy, and using that to cheat.

So what do I do?

I re-purpose adventure modules for use in new genre

The easy way would just be to rename everything and change background and setting details, but I wouldn’t be satisfied with that. Oh no, not me. And it’s not just that most old games weren’t written for a style of play that I particularly enjoy.

I’ll take a game and render it down to its bare components of plot and character, then rewrite it in a new genre, usually for a new system. That hack n’ slash dungeon crawl becomes a postmodern assault on a drug czar’s compound. It’s a bit more involved than just filing off the serial numbers, but I wouldn’t consider it very intensive as far as creativity goes; it’s just extrapolation and interpretation.

My good stuff, the majority of my effort goes right into my writing, for the benefit of my readers.

The post Repurposing Old RPG Materials appeared first on Michael Coorlim.