Alom Shaha's Blog, page 3

May 3, 2012

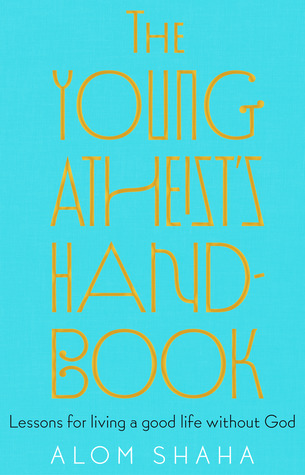

UK Book Launch Event

UK Book Launch

[image error]It’s still a couple of months until my book will be published in the UK (July 17th), but Biteback have decided on this beautiful design for the cover of the UK edition and the lovely people at the British Humanist Association have organised an event to launch the book with A.C. Grayling, Samira Ahmed, Robin Ince and Adam Rutherford all kindly giving up their time to speak.

The launch event will take place at Conway Hall in London on 10th July and is open to the public. Tickets can be purchased here.

April 22, 2012

World Book Night

It’s Shakespeare’s Birthday today, a date which has been chosen by the organisers of World Book Night for “a celebration of reading and books which sees tens of thousands of passionate volunteers gift books in their communities to share their love of reading”. The project is not just about celebrating reading but about reaching out to those who “have never discovered the value or pleasure of reading”.

The video below is one of a series of “Lessons from the Young Atheist’s Handbook” I intended to release around the time of the UK publication of my book but I’m putting it out there today because it’s about why I love books and it feels like today is an appropriate day to share it:

April 13, 2012

Revision Videos

It’s the Easter holidays and I’m hoping my A-level students are using at least some of the time to revise. I’ve been sending them regular emails reminding them to study and including useful web links when I find them. I’ve recently come across a whole series of A-level Physics Revision Videos on YouTube as well as a single 15 minute video that claims to cover all the electricity in the AS syllabus for the AQA course.

I’m impressed by the guys who made these videos - the videos are clear summaries of the content and must have taken a lot of time and effort to make. However, I’m not convinced that just watching such videos is terribly useful as a form of revision. My advice to my students has been to watch the videos in short chunks and make notes - to write down the information as well as simply watching and listening. I can’t help but feel a better form of revision would be for students to try and make their own such videos - something they could easily do alone or working in pairs, using the video functions that most of them will have on their mobile phones.

I’m keen to hear thoughts from other teachers on this and on any other ways of revising that might be effective.

UPDATE: Thank you to Carol Davenport who has provided this link in the comments to an activity sheet for students to complete while watching a video.

UPDATE 2: Peter Upton has provided a worksheet to complete while watching the above video. Download word document: elecvideosummary.docx.

April 9, 2012

The Use of Demonstrations in Science Teaching

A couple of weeks ago, I took part in a live recording of the Guardian's Science Weekly podcast which was also filmed for the Royal Institution's Ri Channel.

Guardian Science Weekly Live from The Royal Institution on Vimeo.

My friend and former teacher Dr Michael de Podesta has written a kind of review of the podcast which prompted me to put up this blog post in which I want to share some notes I made on doing science demonstrations as part of my work as a Nuffield Education Fellow last year:

Demonstrations, like whole class practicals, are an "activity which involves at some point the students in observing or manipulating real objects and materials". Like whole class practicals, demonstrations can be made more effective by proper planning and having clear learning objectives in mind. In his essay The Art of Effective Demonstrations, David A. Katz says, "An effective demonstration should promote good observation skills, stimulate thought, arouse curiosity, present aspects of complex concepts on a concrete level, and, most important, be the basis for class discussion"

Demonstrations provide an opportunity to engage students in a different way to other types of lesson activity, in particular, they can provide an opportunity to insert some drama and entertainment into your lessons. Dr Paul McCrory, in his essay "Developing Interest in Science Through Emotional Engagement" writes: "There is a very wide range of positive emotions which teachers can foster through the way they teach science - for example, curiosity; anticipation; uncertainty; surprise; intellectual joy of understanding; wonder; sense of imagination; amusement; sense of beauty; and amazement… Developing positive emotional responses in the classroom also helps to cultivate effective relationships between the teacher and the pupils."

In some situations, it may be more appropriate and indeed more effective to carry out a demonstration instead of carrying out a class practical - for example, students have traditionally observed Brownian Motion in lessons where they individually (or in pairs) use a smoke cell and microscope to observe the phenomenon. This video shows how the same practical can be done more effectively as a demonstration.

Learning Objectives

As with all practical work, be clear what it is you want your students to learn from the demonstration. Ask your self "why am I doing this demonstration?" and "What do I want my students to learn?"

Encourage Discussion and Questioning

This is perhaps the single most important thing to bear in mind when carrying out a demonstration as part of your lesson. Ask the audience to explain what happened and why and, if necessary, guide students to the correct answer. Asking your students "Predict, Observe and Explain" or even "Predict, Explain Prediction, Observe and Explain Observation" can be a useful way to structure your demonstration.

Preparation and practice

a) Make sure the demo works. If you end up having to say "X should have happened here", it defeats the point of doing the demo and can makes you look a bit stupid to your students. This means preparing the demo properly and practising it repeatedly to make sure that it is reliable.

b) Make sure the demo works well. There's a world of difference (and a lot of effort) between a demo that sort-of works, and one that works really nicely. Find the time to practice and rehearse the demo properly so that you are confident in managing all of the things which you need to do automatically and can therefore focus on interacting with the pupils when presenting the demo.

Learn from each "performance" and incorporate the "happy accidents" and interactions which spontaneously occurred into your plan for when you do the demo next time - write them down or you will forget these gems.

Visibility

Seems really obvious, but you must make sure that your students can see the demo. if they can't all see you (and the demo) or hear you clearly, your lesson will not be effective. Pay attention to size and lines of sight and carry out the demo from the most appropriate position in your classroom - which is not necessarily the front of the class. Ensure that no part of your body obscures your students' view. If you have them, use "demo" versions of standard apparatus, for example, large ammeters in physics or large beakers for reactions in chemistry. You can make small demonstrations easier to see by using a video connected to your whiteboard.

Focus student attention

Prepare students to observe what you want them to see with effective discussion beforehand. During the demonstration, bring their attention to the things you want them to see.

Repetition

If possible, repeat the demonstration - this will allow you draw attention to things students may have missed first time. It will also allow you to tease out students' hypotheses about what is going on and help refine their observational skills. It also allows you to highlight things that may come up in discussion.

Involve students

If it is safe to do so, get a volunteer to carry out the demonstration.

Showmanship

You can engage your students attention and enhance their enjoyment of your lessons by indulging in some showmanship with a demonstration. David A. Katz advises teachers to "Show surprise at the results. Show dismay at demos that go particularly slow. Presenting demonstrations is fun. Ham it up with props, costumes, funny signs or slides, jokes, etc… If you are enjoying yourself, so is your audience."

Explanation

Make sure you know the correct explanation for the demonstration. Many popular websites etc. contain inaccurate or even entirely incorrect explanations for popular demonstrations so research the science behind the demonstration properly, from "serious" educational sources. If possible, and if appropriate (often much better), "work out" the explanation with the class.

Summarise

Ensure that you go over what students were supposed to see from the demonstration and learn from the explanation. Ask your students, "what did you learn?" The discussion at the end of the demonstration is essential and you should plan your lesson to guarantee that there will be time for it.

Coping with Failure

Sometimes, even with the best preparation, demonstrations do not work as planned. There are number of ways you can deal with this, including having a second go (if time and resources allow) or showing a video of the phenomenon. A "failed" demonstration may provide you with an opportunity to discuss with your students why the demonstration didn't work.

Safety

As with all practical work, ensure that you have done a risk assessment. Check your apparatus beforehand and use safety shields and goggles where appropriate.

The above notes have been inspired and informed by the work of David A. Katz, Dr Paul McCrory, Dr Ben Craven, Jonathan Sanderson, Elin Roberts and many others.

April 7, 2012

A snack for thought?

I was recently interviewed for 4thought.tv - "a series of highly personal short films, broadcast 365 days a year, reflecting on a broad range of religious and ethical issues, and aspects of our spiritual lives." According to Channel 4, "these 90 second films challenge some traditional views, providing a platform for both scepticism and devout religious beliefs."

I was recently interviewed for 4thought.tv - "a series of highly personal short films, broadcast 365 days a year, reflecting on a broad range of religious and ethical issues, and aspects of our spiritual lives." According to Channel 4, "these 90 second films challenge some traditional views, providing a platform for both scepticism and devout religious beliefs."I was really impressed with the way the film-makers treated me - they were really straight with me, they dealt kindly with my concerns and convinced me that they genuinely wanted to put me and my views across in a positive light. You can watch my film here.

It must be challenging to make a 90 second film of this sort and I can't help but feel the time slot is just that little bit too short to be satisfying in terms of providing food for thought. I suspect I may have cut a different film from the hour or so of interview footage that was shot - the thing about bacon seems a bit out of place, for example, and I would probably have included other points I wanted to make. However, I'm really glad I did it and I really liked the bit of the interview they chose to end my film with.

March 31, 2012

Goodreads Giveaway of The Young Atheist's Handbook

font-style: normal; background: white; }

.goodreadsGiveawayWidget img { padding: 0 !important; margin: 0 !important; }

.goodreadsGiveawayWidget a { padding: 0 !important; margin: 0; color: #660; text-decoration: none; }

.goodreadsGiveawayWidget a:visted { color: #660; text-decoration: none; }

.goodreadsGiveawayWidget a:hover { color: #660; text-decoration: underline !important; }

.goodreadsGiveawayWidget p { margin: 0 0 .5em !important; padding: 0; }

.goodreadsGiveawayWidgetEnterLink { display: block; width: 150px; margin: 10px auto 0 !important; padding: 0px 5px !important;

text-align: center; line-height: 1.8em; color: #222; font-size: 14px; font-weight: bold;

border: 1px solid #6A6454; -moz-border-radius: 5px; -webkit-border-radius: 5px; font-family:arial,verdana,helvetica,sans-serif;

background-image:url(http://goodreads.com/images/layout/gr... background-repeat: repeat-x; background-color:#BBB596;

outline: 0; white-space: nowrap;

}

.goodreadsGiveawayWidgetEnterLink:hover { background-image:url(http://goodreads.com/images/layout/gr...

color: black; text-decoration: none; cursor: pointer;

}

Goodreads Book Giveaway

The Young Atheist's Handbook

by Alom Shaha

Giveaway ends April 29, 2012.

See the giveaway details

at Goodreads.

Enter to win

March 8, 2012

Juris' Story

Hi Alom,

It was a pleasure to meet you yesterday at your book reading and to engage with you in the ensuing discussion. You asked me inside the cover of my copy of your book to forgive you for being a little harsh on "agnostics". I didn't, and don't, take offence.

I've read your book from cover to cover since then. It was compelling reading. I disagree with none of the points you make in the book, although there are some things I could add to, but then so could you, as you so clearly state.

Having thought a bit about why I disagree with you on what you said at the pub about agnostics, it probably stems from our differing life experiences, even though we have some startling parallels in our life stories. I could engage with you in an almost page by page discussion of the points you make in your book, agreeing with or embellishing what you say, but I doubt that you have the time or that that would necessarily be productive.

So I'll try and paraphrase or distill some of my thinking for you, if you're interested, as to why I differ with you on the one issue - the issue of how I label myself.

I think I'm old enough to be your dad, but I consider myself your equal, probably not in terms of intellect, but as a human being. I have a lot of friends of both genders, some of whom are much older or much younger than me, but I give all my friends equal space and appreciative attention. As you can imagine, I abhor ageism, sexism, racism, homophobia and prejudice of any kind against anyone (and indeed against any being, such as occurs with an anthropocentric view of the world). That's not to say that I don't recognise my own propensity for prejudice, because, as you yourself say in so many words, none of us is actually rational. In fact there have been carefully controlled scientific studies that have shown that we tend very much jump to conclusions and are incredibly adept at instantly finding convincing justifications for those conclusions.

A little background about myself. I'm Latvian of origin, born in Riga, Latvia, two years before the end of the Second World War. A year later my mother took me as a babe-in-arms to Germany, fleeing from a return of Russian troops to Latvia under fear of persecution and possible deportation to the Gulags of Siberia. My father turned up in Germany and found my mother in a refugee camp when the war ended, having spent most of the war years on the Eastern Front, fighting the Russians with the Germans. My sister was born three years after me in Germany. In my teens I discovered that my mother had miscarried a child before me. She was a very attractive woman and must have also suffered a lot of unwanted attention and who knows what else in Germany, under constant bombing attacks while travelling across it by train with me as a sickly baby.

The refugee camps, euphemistically called Displaced Person camps, were bleak, and hunger and cold were frequent problems, not that I as a child growing up there was at all aware of such issues. I spent some four years there, plus some six months in an awful camp in Naples, and eventually joined my father in Tasmania who went there ahead of me, my sister and my mother by a year. My mother was a sensitive, loving soul, interested in classical music, literature and poetry, while my father, who had been a veterinary surgeon in Latvia, was rather self-centred and distant from us kids, and was put to work in a sawmill in Tasmania.

My two years in Tassie were like paradise after the refugee camps. We lived on a farm amidst abundant natural features and I walked through the fragrant Australian bush to and from school. I flowered and quickly learned English, which at the age of five or six is a cinch. My mother already showed signs of mental illness and at some point threatened that if I didn't behave, she'd put me in a children's home. Not much later I found myself, together with my little sister, in a children's home in Melbourne, run like an army camp, dominated by fear and physical punishment for the slightest infringement, sure that I had been so bad my mother had had to put us there. She had left my father and taken up residence separately while working, and visited us once or twice a month for a few hours. I closed up completely, barely spoke at school, and was thought to be mentally slow.

After some six or eight months my father found her and rejoined her and we were taken out and reunited as a family. I was placed in another school with a lot of middle-class kids where I had great difficulty adjusting and experienced a lot of prejudice and bullying. For at least a year I spent every school recess and lunch-time hiding up a tree, often defending myself against gangs of bullies on the way home from school. My father built our house and my mother worked from home as a seamstress under sweatshop conditions. He went off building houses for several years all over the countryside and I saw him a couple of times a month for a day or two. When he was home, I was afraid of severe beatings from him, either with his belt across my buttocks or around my ears with his open hand that occasionally threw me off my feet, always in a white rage. In fact he seemed to have only one tone of voice and that was anger.

Towards the end of my primary school experience a new school opened closer to home which attracted the children of many working-class and immigrant families, and I switched to that school. Within a couple of months I was school captain and had a bunch of friends.

On Saturday afternoons during my primary and early secondary school years I took my little sister by tram or train to Latvian Saturday School, an hour and a half away by public transport. Here we were indoctrinated into being good little Latvians and Latvian Lutheran Christians at that. At home there was no emphasis on religion. It was paid lip service only. I can thank that period of my life for becoming truly bilingual, although I have learnt well a couple of other languages since and a smattering of a huge number of others.

Melbourne had three government high schools at the time that drew select students from all over Melbourne as well as locally. We didn't live locally, but apparently I passed an exam that gained me entry to the school my mother had selected for me. I did well in the highly intellectual company I now kept and under the tutelage of teachers I mostly respected and admired. I had good friends at school, including a close Jewish friend, and still keep up with many of them (although the Jewish friend didn't recognise me thirty years later back from a couple of decades in Israel, even though we'd wagged classes together to play chess in the locker-room or to go see a film in town). Home life was becoming increasingly erratic. At some point my mother almost died of another miscarriage and she was at times taken away by police to be put in a mental asylum. This was of course extremely disturbing for me and probably more so for my sister. When my mother was at home, her behaviour was increasingly erratic. Living with her I felt no stability - as if my feet were constantly on shifting sand. She suffered from auditory delusions and was convinced we were all plotting to kill her. No matter how I tried to convince her otherwise, she only had occasional periods of lucidity.

It was around this time that I became increasingly curious about religion - Christianity that is, because there was nothing else around. On Sundays I would catch a tram to town and visit various churches to see what was going on. I started to listen to a radio program run by a fundamentalist American Christian sect, read the Bible every day (I got through all of the Old Testament once and the New Testament several times), and became quite convinced that I had discovered the real truth. As could be expected, I became intolerant of other views and my behaviour at home became excessively meek, never protesting any punishment. This is the one time I can remember that my father did something truly good for me. He forbade me to listen to the religious program until I reached the age of 21, the age of majority at that time. Like a good son, I obeyed. By the time I was 21, I was no longer interested in the fire and brimstone sermons and rejected the program's teachings, though still embracing what I thought was a Christian outlook.

I was apparently destined for great things. I wanted to become an architect and won a scholarship to Melbourne University. But I had become dysfunctional in my study methods, probably because up till then I had been able to get by with last minute cramming for exams. At the age of 18, which seems laughable now, I ran away from home and university and sought work hundreds of miles from home, returning only when I gave in to my mother's emotional pleas. I worked at a desk job full-time and many aborted part-time courses later I re-enrolled for architecture, was accepted, but within eight months had a breakdown and attempted suicide. It was a call for help. I got work in a government department as a stop-gap job, but finished up stopping that gap for the next thirty years. Meanwhile my mother took her own life when I was 22. I couldn't speak about it for twenty years. I felt I was to blame.

I had a girl-friend from the age of 7 to the age of 19. We used to sit in the park before Latvian School holding hands and wrote love letters to each other. We were 16 before we kissed. Three days after breaking up with her, I met my current wife. We met in a Latvian church youth camp. We've been married for 41 years, have two children and four grandchildren. We married when she was 20 and I was 25. A year later we were overseas on the first of two postings lasting in total almost seven years. My posting to Athens entailed occasional field trips to Cyprus, Beirut and Tel Aviv. I witnessed the unbridled, irrational prejudice of Greeks against Turks, Turks against Greeks, Arabs against Jews, and Jews against Arabs. In Manila I became involved in refugees from Vietnam, coming across by boat, escaping the war zones and I was recruiting the first Asian immigrants to Australia.

On return to Australia, I wanted Canberra for career opportunities and to return to study. I got a degree majoring in sociology and economics working full time and studying full time, all at the same time, while riding my bicycle to and from work, home and uni, helping the kids with their homework, and helping my wife with her supplementary studies, and later, training for a marathon. I did very well with my studies. It was the sociology that fascinated me. The economics you could keep. I could see it was flawed and market economics in the real world excluded externalities to our own detriment - something borne our by the Global Financial Crisis and now recognised as needing application. I wanted to know what made people and societies tick. That was where I slowly lost all my religious beliefs, realising that so much of what we assume under religious guise is so much bunkum. It is also where I strengthened my belief that prejudice is the biggest problem facing any society - in fact any group of people and even any individual.

I retired early from my career in the public service - at not quite the age of 53. My kids had grown up, they had finished uni, had jobs, had moved out of home, my mortgage was paid off, and I couldn't see the sense in continuing to go to work, just in order, it seemed, to buy a car to go to work in. I could manage on what I had saved and on my superannuation eventually. My wife continued to work as a teacher for some years, and that helped the budget too. I turned my attention to voluntary work and have been engaged in various organisations in various capacities for all the years of my retirement. One of the issues I have been heavily involved in is development aid in eastern Indonesia. I have travelled there half a dozen times in a monitoring or training role. I have a deep sympathy for the region, its burgeoning population and the need to provide clean water and sanitation and education particularly for girls. Although the region is mainly Christian (which is probably partly why it is so neglected by the central government), I have over the years spent many social occasions with Muslims in Australia in support of the work we do there. I am also active in the Latvian community in a couple of capacities, catering basically to people still living in the past who find comfort in monthly meetings that celebrate their connection with things Latvian. Besides, I have been a vegetarian (for philosophic reasons) for almost twenty years, and a closet one for the preceding ten years. I have all along had a brilliantly good relationship with my children and my grandchildren. My relationship with my spouse has been a bit up and down but is tenable and sustainable.

Okay, that wasn't so brief, but I think it shows you in essence the parallels and divergences of our respective experiences of life.

In my view, humanity has always faced a huge amount of uncertainty. That uncertainty is evident everywhere, and we don't actually have sufficient information to make rational decisions in an uncertain environment. (Even such a thing as our eyesight depends on illusions.) Accordingly we seem to have evolved to cope with uncertainty. We do that by categorising and labelling, and using these categories and labels to interpret the world. These categories and labels enable us to jump to conclusions without real evidence to back up our categories. But we are very quick to rationalise our views. The thing is of course, that someone else, or another group of people, or another society, or another religion, uses different and often partly overlapping or mutually exclusive categories, interpreted differently and leading to different conclusions. Some years back I made a thorough study modelling horse-racing data to see if there was any money to be made from it, using the government-run betting agencies. I saw how easy it was to fool oneself with statistics, especially if applied retrospectively. I though I was onto a goldmine, but eventually I had to admit to myself that I was wrong. I came to the conclusion that in practice it is impossible to win in the long term because the government creams off too much and because graphical evidence showed me that there was unpredictable skewing in the results long term - either done deliberately by the agencies or by big bettors who bought unfair rights with government agencies (the latter has since been confirmed in the press). I bring this up just to give an example of how easily we fool ourselves that we have all the rational evidence to make a rational conclusion, when in fact we don't.

Today we clothe much of that uncertainty in a kind of certainty, living in our cocooned urban environments. But the uncertainty, especially in times past or in societies not yet enjoying the benefits of the developed world, is instrumental in people reaching out for something to believe in. So they believe in any old stuff thrust on them - all sorts of superstitions, including religions. One modern day example is the belief many people hold in alternative medicine, as if it had some legitimacy. It takes a kind of anti-scientific view of the world to believe in any of that stuff.

I don't believe in God, or any kind of supreme being, and yet, I call myself an agnostic. As I said, that's because I allow that there are things I don't understand and therefore I can't be absolutely certain that there is no God, whatever way that might be defined. I don't wish to put myself in an absolute category, because to me absolute categories are fundamentalist in nature, and that's one thing I shy right away from. Also, some of my friends are deeply religious in one way or another (usually not Christian, but of New Age conviction). Out of deference to their beliefs and not wishing to harm them psychologically (because some people benefit psychologically from their beliefs), I tell them that I allow that there could be a supreme being or entity of some kind. I do say that to me that is more likely to be my own higher self, perhaps in some kind of union with other higher selves of other people (which amounts to a kind of Jungian philosophy). But I don't entertain the idea of an afterlife or any anthropomorphism. I don't know where I came from, and that doesn't bother me at all. Why should it bother me where I'm going? Why should a God try to bribe me with Heaven? I personally don't need that kind of option. I know I arose from star-dust and I'll return to star-dust. That's fine with me. I don't need to entertain the thought of my consciousness or soul surviving me. I think such a need arises from anthropocentric and egocentric thinking. Other beings have other marvelous senses we don't have. Other beings have just as much right as we do to a heaven of sorts, if we do. But there's no sense in any of that. We just merge back into the universe, and I'm very happy to be part of that, as a conscious individual right now, but as unconscious but malleable star-dust when the time comes.

I see a parallel too between how Australian society views atheism versus agnosticism or veganism versus vegetarianism. The former in each case seems more strident and categorical to most people - fanatical even. In Australia in fact most people are indeed atheists by your definition, but on a very thin veneer of religiosity. Most young people have no idea of Biblical allusions which were once the staple of just about any piece of writing or discussion. Churches everywhere are closed or used in other ways. People just don't see themselves really as Christian. People lose their religiosity gently and slowly in the same way that they lose their belief in the Easter Bunny or Santa Claus. Mostly religion is not reinforced at home. Only religious schools reinforce the myths that we both despair at for the good of the world. In fact I've had people call others Christians only in situations where those others are fundamentalist Christians. I think the reason for the slow decline in religiosity has been the slow ascendancy of secularism in Australian society, together with increasing living standards easing the kind of uncertainties I spoke of earlier, and immigration over decades and generations producing a melting-pot and a more tolerant society, even though it is uneven.

Last year I spent a fascinating time in Central Australia for two weeks, sleeping under the stars, searching for and finding previously undiscovered Aboriginal artifacts and cave paintings, as part of a push to empower the local Aborigines. I studied up a lot about Aboriginal anthropology and could discuss with you very interesting aspects I found about their spiritual lives. Their societies, going back 40,000 years or more, were devoid of concepts of divinity but rooted rather in animistic beliefs in spirits and in timelessness - a notion they still live with that merges the distant past with the present and the future, not only in time but with the land and with their cultural systems. They were much better guardians of Australia's fragile ecosystems than we have been. Their cultures and way of life have been utterly destroyed. I'm very much aware, both as a result of my experience as a Latvian, and as a student of sociology, that language seems to underpin culture, and culture underpins identity. When you destroy one or both of the first two, the third is also heavily affected, resulting in psychological dysfunction. That's another reason to be wary about trying to force sudden change in religious beliefs on people. I know that isn't the aim of your book - in fact quite the opposite - but agnosticism could be seen as a transitory position to atheism with a legitimate place along that route to safeguard sanity.

A trip to China less than two years ago spurred me to refresh for myself and study up, among other aspects, Chinese history and religious beliefs. I found that fascinating too, especially the influence of Buddhism and Confucianism on present-day Chinese thinking. Both are really philosophies rather than religions, although both acquired in practice various and disparate sets of rigidities and rituals. Actually, Confucianism was rigid and ritualistic from the very beginning. In part I see myself as post-facto Buddhist, only relating to its philosophical components. Meditation is indeed a technique I find helpful and quite amazing, not that I'm a regular practitioner by any means.

One reason why I think people in the USA and people from somewhere like Latvia have great difficulty with assimilating any notion of atheism is their experience of Soviet atheism as a component of state brutality and totalitarianism - for the US less directly than for East Europeans. The USA's roots in most of its early immigrants escaping form religious persecution in Europe seems to be the main reason for a continuing emphasis on religiosity as the basis of American culture.

On the other hand, I do recognise that paradigm shifts do occur for some people as a result of a kind of shock-and-awe, to plagiarise a recently popularised term from a very different context. I well remember decades ago sitting in a suburban Melbourne train thinking to myself that the young lass, who sat down near me wearing a T-shirt proclaiming animal rights, must be out of her mind. It was after reading about the shocking things that go on behind the scenes in the meat industry and the way that in Australia cruelty in farming practices is exempt under legislative arrangements that I had a sudden change of heart. So I suppose that shock-and-awe tactics can also result in people changing how they see themselves as non-believers rather than believers.

With deep respect for your writings, and the hope that some of this may prove of some use to you in interpreting Australian society and understanding my views better, wishing you the very best in all your further endeavours,

Juris Jakovics

March 3, 2012

Teaching Notes

My lovely friend (and award-winning teacher) Kylie Sturgess has kindly written some teaching notes for The Young Atheist's Handbook, which you can download at the end of this post.

As both a teacher and a writer, I'm often asked by friends and readers to recommend books that will help them learn more about atheism. People seem to be particularly keen on books that talk directly about the challenges that people growing up in religious communities face - especially if they are stories which question the traditions and way of life that the author has been brought up in.

Of course, authors like Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Richard Dawkins, Dan Barker, Nica Lalli and Christopher Hitchens immediately spring to mind - all wonderful recommendations and well-worth reading. Yet there's still a fairly untapped minority out there, that (for several reasons) we should encourage. They are people like Alom Shaha: a UK science teacher, raised in the Bangladeshi Islamic tradition. By taking the important, crucial first step of speaking out and writing a book - The Young Atheist's Handbook: Lessons For Living a Good Life Without God - he has not only been incredibly courageous and forthcoming about his fascinating life, but has provided us with a valuable learning and teaching resource.

I'm very fortunate to have taught Religious Education and Philosophy in Australia to high-school students - and not just because I have had the opportunity to work with wonderful people of all ages and gained access to a number of resources that investigate and interrogate the nature of faith. My profession has also has given me some insight as to the challenges that young Muslim people face in the modern world and how their experiences can greatly vary.

It is for these reasons that there needs to be a book that can be used in classrooms and reading groups, in order to promote discussion about these issues, regardless of the reader's faith (or lack of it). By creating reading notes for this book, I hope it will not only enhance the experience of learning about Alom's story, but encourage more educators and reading groups to seek out and support similar voices that reflect the diverse experiences of atheists.

Teaching Notes for The Young Atheist's Handbook.pdf

February 26, 2012

I cannot write

It's been nearly six months since I finished my book and I haven't really been able to write since. I've sat down many a time at my desk and found the tap that had flowed so gushingly last summer, blocked and barely dripping.

I've spent the last couple of days surrounded by other writers and I have been inspired by them and their stories.

I have felt driven to write, yet I find I cannot.

I cannot write of Holly and Michael, kindred spirits I have encountered far from home, but with whom I felt immediately at home.

I cannot write of Frank Sheehan, a man of God, whose empathy and compassion are so great that he can be evangelical about a godless book.

I cannot write of the sensation in my stomach when a stranger approaches, holding a copy of my book (my book!), asking for me to sign it. It is not pride. It is a mixture of gratitude and pure, unadulterated joy.

I cannot write of the feeling of giddiness at everything, yes everything, going well in my life for what I know is a brief moment of perfection.

But neither can I write of the niggling feeling of guilt that is bothering me because I cannot simply take the happiness, break it apart, and divide it between the people I love.

I cannot write. But, god, I want to.