Matador Network's Blog, page 2284

April 14, 2014

4 worst places to spend the night

Photo: Emoya Luxury Hotel & Spa

4. Euro Disney

Look, I get it if you want to go to Disneyland or Disney World. Disneyland kinda fits into the whole Southern California, ‘Let’s all go to the movies!’ thing, and Disney World…well, you’re in Orlando, what else are you going to do?

But if you’re set on your tackiness having a vaguely international flair to it, go to Epcot. Don’t go to Euro Disney. (It’s actually been rebranded as “Disneyland Paris,” but I’m not going to condone that crime against one of the most culturally rich cities in the world.) I know it’s tough being a parent, but maybe take your kids to a real European castle, like the gorgeous Mont Saint-Michel in Northern France, or to Neuschwanstein Castle in Bavaria, which the Disney Castle is based off of.

You’re exempted from my scorn if you live in France, and your kids won’t shut up about Mickey Mouse.

3. Any safari hunt

A few months ago, American television personality Melissa Bachman got into some deep shit for tweeting a picture of a male lion she hunted and killed in South Africa. She paid a hefty fee to kill the lion, and she did it all legally. Money from such hunts actually contributes a lot to local conservation and anti-poaching efforts, which are usually pretty cash-starved, so in that sense her hunt was a good thing.

But as a whole, this is an incredibly creepy, perverse practice you shouldn’t participate in. I appreciate that they try to make the money from these hunts go towards protecting the not-shot-in-the-head animals, but it feels less like conservation and more like demanding a pound of flesh for your money. Or however many pounds the lion weighs.

I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with hunting for food. It’s a hell of a lot more natural than eating meat from a factory farm, and it requires you to put at least some effort into your meal. But you’re not flying to Africa and paying $125,000 to get a square meal. You’re doing it because you want to kill something exotic. Which is, at the very best, super creepy.

Hunting for sport should be sporting — i.e., you should be on the same level as the lion. He’s got claws, you get a knife. And there’s just no need to be killing species that are listed as ‘vulnerable’ and have been on the decline for the last half century. Lion-focused non-killing safaris are a great way to appreciate these animals without killing them.

One of the major problems here is that African conservation orgs are severely in need of funding, so they have to make a deal with the devil: Let a few rich Americans kill a lion to save the others. If we donated to organizations that protect wildlife in greater numbers, this choice wouldn’t have to be made.

2. The Hans Brinker Budget Hotel in Amsterdam

I feel conflicted about adding the Hans Brinker Budget Hotel to this list. It doesn’t appear to be that bad a hotel, as far as budget hotels go. But they advertise themselves as “the worst hotel in the world.” The HBBH has clearly adopted the lean in approach to advertising, and rather than taking their horrible customer reviews and trying to improve their property, they’re just advertising how bad it is. Here are some of the lines they’ve used:

“Sorry for being excellent in losing your luggage.”

“Hans Brinker Budget Hotel. It can’t get any worse. But we’ll do our best.”

“Now even more dog shit in the main entrance!”

“Improve your immune system: Hans Brinker Budget Hotel, Amsterdam.”

The hotel’s online reviews range from the, “Oh my God, this was awful,” to the, “Meh, not as bad as they built it up to be.” It seems that, to some extent, it’s turned into a sort of destination for the type of Amsterdam tourist who wants a particularly depraved stay (although that might be redundant: I can probably just say “Amsterdam tourist”).

Some of the reviews comment on it having a pretty decent party atmosphere, even if the hotel does suggest you use the curtains after showering instead of the towel. So Hans Brinker earns a place, not for actually being all that bad, but because they want to be so bad that they’ve ascended to the same plane as punk rock and have basically become the Sex Pistols of shitty budget hotels.

1. The Emoya Luxury Hotel Shanty Town Accommodations

The winner for the worst place on the planet to stay is the Emoya Luxury Hotel & Spa Shanty Town Accommodations. I can’t explain it any better than the people at Emoya, who, by this description, are clearly be-monocled, Victorian-era, British one-percenters:

“Now you can experience staying in a shanty within the safe environment of a private game reserve. This is the only shantytown in the world equipped with under-floor heating and wireless internet access!”

If that makes you want to vomit until you die, be comforted that there are authentic shantytown touches added, like ‘long-drop toilets.’ Because we all know the universal features of extreme poverty are warm feet in the morning and having to wait a second for the splash when you poop.

The post The 4 worst places on the planet to spend the night appeared first on Matador Network.

Old woman dances amazingly

I THINK IT’S silly whenever I hear a friend of mine groaning about “getting older.” Personally, I look forward to growing older, because it affords me new and different opportunities I couldn’t have while I was young. Do our bodies begin to decay as time passes? Probably. But that doesn’t keep some people from doing the things they love, and kicking ass in the process.

In other cultures, elders are revered, and admired. I think we’ve begun to underestimate older populations in Western society, which causes us to be ageist. Maybe if we stop hating on getting older, and start embracing the experiences it affords us, we can enjoy our lives just as much as this 80-year old woman does (the action starts at 1:40).

The post This 80-year old woman proves that getting older doesn’t have to suck appeared first on Matador Network.

Where to see underground music in LA

Photo: SGV FILMWORKS

First off, where NOT to go

I’m sure you’ve heard of names like The Viper Room, The Roxy, The Whiskey A Go Go, The House of Blues. I’ve heard of them too but I’ve never been there, because no one really goes there. Seriously! Don’t get me started on how lame Hollywood is.

For the dance floor

Only a few years ago, Los Angeles was a wasteland for any electronic music that wasn’t super cheesy Avicii EDM stuff. Now just about every weekend underground warehouse parties are booking legit people like Julio Bashmore, Tensnake, and Jacques Greene.

A Club Called Rhonda is probably the leader in LA’s house music scene, held every first Friday of the month in Silverlake’s Los Globos club. They bill themselves as a Polysexual Party Palace, meaning it’s super gay friendly and people wear all kinds of crazy shit. Think wedding veils, mesh suits, haute couture samurai troupes, ’60s flight attendant drag. It’s pretty popular, so I recommend getting there before 11.

Mount Analog is a record store based in Highland Park that specializes in darker electronic music. They host a regular party called Nuit Noire. Think more gothy and industrial than regular rave stuff. Check out their calendar for smaller shows around downtown LA.

Fade to Mind, VSSL, and Body High are a couple of record labels who also regularly host warehouse parties in undisclosed locations, so look them up as well. The best way to get into the parties is to follow their Facebook pages, where they announce these events. Once you RSVP, they’ll email you the location a few hours in advance. They’re generally a little bit east of downtown and can be best accessed by taxi or Lyft.

For the mosh pit

If your idea of fun involves dodging elbows and shoving people in a sweaty mob, LA has plenty of that. For years now, an all-ages DIY space known as The Smell has become SoCal’s indie rock epicenter. It’s hidden away in a gross little alleyway that smells like pee and is patrolled by a homeless “security guard” (his name is Daniel and he’s cool, buy him a taco or something), but all the shows are less than $10 and you can find local acts there like FIDLAR, Wavves, HEALTH, The Garden, Best Coast, and so on.

Getting there isn’t too hard if you know what you’re looking for. On Main Street and 3rd, there’s a

bar with a sign that consists only of five stars. They regularly host punk, hardcore, and metal acts during the week, and it’s a great spot in itself. Go around the shady Mexican bar and into the alleyway. Look to your right and Daniel should be there to direct you to The Smell.

In the summertime, Fuck Yeah Fest regularly books super classic acts like My Bloody Valentine and Descendants. FYF actually began as a ramshackle festival consisting of bands from The Smell, but has now expanded to a two-day affair with a pretty diverse lineup. Definitely my pick over bro-chella anyday. Bring a scarf or handkerchief to cover your face, because it gets really dusty.

Burgerama in the OC is also a good place to look for indie and punk rock in the spring, and don’t forget to check out the Echoplex in Echo Park for shows throughout the year.

For beats

No mention of LA’s music scene is complete without mention of its “beat scene,” which can best be described as electronic music produced with a hip-hop state of mind. Flying Lotus is the most visible of this movement, along with all the folks at his Brainfeeder label. They regularly play at Lincoln Heights’ Low End Theory club, which has become so popular they often can’t even announce who’s playing because it causes traffic problems. Thom Yorke is known to play impromptu DJ sets here, so don’t miss Low End Theory.

The post Where to see underground music in LA appeared first on Matador Network.

Signs you were born in DC

Photo: Lynford Morton

1. You avoid the red line when at all possible.

2. You would never pay $1100 a month to live in Columbia Heights.

3. Your standards for formal education/job success are unreasonably high.

After going to high school alongside children of senators, high-performing lawyers, and diplomats, you never got the message that grad school isn’t a possibility for most people, or that you will not die unhappy, poor, and alone if you do not attend.

4. Which has made you pretty, um, neurotic.

Unrealistic parental expectations and a dearth of public space have likely culminated in meds for anxiety disorders.

5. You get so used to the question ‘What do you do?’ that you make up answers for fun, such as ‘Perform in a circus,’ or ‘It’s classified.’

6. You know what go-go is.

7. Your standards for food are comparatively low.

You grew up with zero local or organic movements. Now there are a few exceptional places, like the Jose Andrés businesses — Oyamel, Zaytinya, and Jaleo — but that’s definitely not the norm.

8. But you do crave Peruvian Chicken, pupusas, and Ethiopian food.

The few food items DC and its surrounding suburbs totally get. And no city has injera as tasty as ours, outside of Addis Ababa.

9. Fort Reno Park is one of your favorite places in the world.

10. Poverty and social unrest were either distant concepts or very real.

For kids like me who grew up in the suburbs, times were good. We went up county to rural pumpkin patches in the fall, had big Christmas trees or beautifully crafted menorahs during the holidays, and had well-funded schools with active PTAs. Because so many of our parents worked for the federal government, there was a buffer against economic downturns.

But for my friends who lived inside DC, poverty was very real. In the ’90s, the city was still recovering from the crack epidemic and widespread corruption, and it wasn’t as good at hiding its flaws back then.

In 1991, the streets of the Mount Pleasant neighborhood erupted into a riot that lasted days. The protesters were largely recently arrived refugees from El Salvador who were fighting against police brutality. Then-mayor Sharon Pratt has said that the riot made the city recognize that “it had to take great strides to move beyond a sense of itself as a sleepy Southern town,” to a cosmopolitan metropolis with many stakeholders and different demographic groups.

11. You go crazy for Kojo Nnamdi.

Every weekday at noon, you feel a surge of happiness to turn on the radio and hear the regionally famous voice of this Guyana-born public affairs talk-show host. All he has to say is, “I’m Kohhhhjo Nnaaahmdi,” over some smooth jazz, and your current life crises will melt away — at least for a couple of hours.

The post 11 signs you were born and raised around DC appeared first on Matador Network.

How to piss off a pregnant person

Photo: Sami Taipale

Touch our bellies without asking.

Whether you’re a friend or (god forbid) a total stranger, please don’t assume our tummies are fair game. We don’t want to be rubbed, massaged, stroked, or informed that because we’re carrying low it’s going to be a boy, any more than a non-pregnant person would want to be touched without any warning, either.

It’s polite to ask, even if you know someone well. Some pregnant people can’t stand being touched by ANYTHING (even their clothes), so making a grab for the protruding belly just demonstrates you don’t value their autonomy as a person.

Ask how many months we are.

This is understandable, and it’s not really going to piss most of us off, but it’s mildly irritating because there are a lot of changes that happen in development, and a month is a REALLY long time. For some reason, people also aren’t impressed by your pregnancy at all until you’re at least six months, so asking how many months along someone is and then raising a bored eyebrow when they say three and a half means you’re discounting that the fetus has fingers, toes, and a heartbeat!

We’re growing the damn thing as fast as we can! Go with what the medical profession does and ask us how many weeks. We get asked that by the doctor so often, we’ll probably automatically tell you the date of our last period, too.

Remark on how much weight we’ve gained.

This is a pretty good guideline for everyone, actually: Just don’t comment on someone’s size. Don’t say they’ve lost weight; don’t say they’ve gained it. Just don’t. Given the fat-shaming endemic in doctor’s offices, chances are we’ve spent our entire pregnancy thus far being weighed and lectured about our food choices. The last thing we need is anyone else jumping on the bandwagon.

Expect us to act exactly the same as before we got pregnant.

The amount of energy and abilities of every pregnant person completely varies — not just from person to person, but from pregnancy to pregnancy…and week to week. The first trimester is notoriously exhausting: I slept for 11 hours a night and could barely climb up the stairs to my apartment without getting winded. Considering I’m used to huge amounts of exercise, this was really weird for me, and I felt pretty sad about not being able to stay awake past 9pm or go out and do things without collapsing face-first into my food.

Tell us we can’t have that glass of wine (or cup of coffee).

You hear horror stories of people taking a glass of celebratory champagne right out of a pregnant person’s hand, or in one awful instance, a barista looking straight past a woman to her husband after she ordered a coffee and asking, “Are you sure you should let her have that?” You heard it here, folks: There’s not a lot of evidence against coffee during pregnancy, and most of what there is is circumstantial. (There’s a link between less nausea in the first trimester and higher risk of miscarriage, and people who are nauseated drink less coffee; therefore people who drink more coffee are also probably less nauseated and more likely to miscarry.)

Ditto drinking. A lot of the studies on alcohol during pregnancy show there’s little to no risk (and some reward) to having a glass of wine a day during your pregnancy, which is quite different than slamming back a row of tequila shots. Please don’t assume you have any idea what’s best for someone else’s body.

Treat us like a vessel for the baby instead of a human person.

I read a memoir awhile ago wherein a woman said she’d read a book during her pregnancy that sternly demanded that every time she ate a meal while pregnant she ask herself, “Is this the best bite I can give my baby?” A human body is more than just a host for a parasitic fetus, and we have opinions, thoughts, feelings, and needs.

We have a lot more going on in our lives than just having a baby, although it’s pretty interesting, exciting, and weird. Try asking us how our day was instead of slapping a French fry out of our hand and saying babies shouldn’t have trans fats. Maybe they shouldn’t, but that’s what I’m in the mood for right now, okay?

The post How to piss off a pregnant person appeared first on Matador Network.

36 maps challenge what you know

The internet has led to a renaissance in mapmaking, with thousands of interactive, illustrated, informational, or just plain silly maps being published on a daily basis. We’ve done a number of other pieces on some of the web’s interesting and weird maps, but there’s thousands more out there, and it can be hard to keep up. So here’s another installment, with 36 new maps we haven’t posted before.

1. Wind map of America

(via)

Check out the live map of America’s winds at Hint.fm. It’s awesome and entrancing (and might help explain your weather).

2. Actual discoveries by Europeans

(via)

These are the lands Europeans actually first discovered — as in there weren’t already millions of people there. It’s much less impressive than what grade-school history classes would have you believe, but it’s still a lot of discoveries for people sailing around the world in wooden boats.

3. Countries by racial tolerance

(via)

This map was fairly surprising to me — I certainly wouldn’t have guessed that Russia was more tolerant than France, and I’m happy to see the US is in the most tolerant group. Or maybe we’re just less open about our racism.

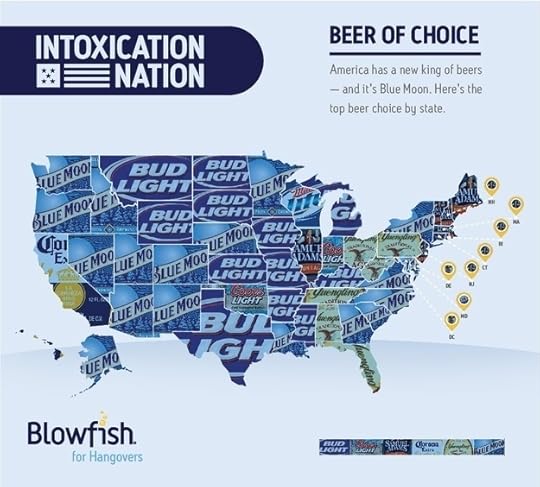

4. America’s favorite beers by state

(via)

You know, with the exception of the giant swaths of Bud Light states, I’m not too ashamed of this map. We’re getting better taste, America.

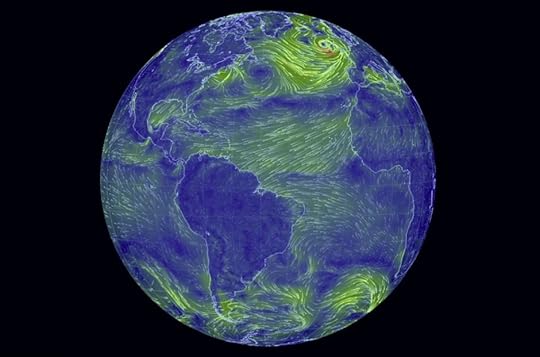

5. Wind map of the world

(via)

Again, this is best seen in the beautiful, real-time interactive live map of the world’s winds, but this is a screenshot of the world’s winds.

More like this: 57 maps that will challenge what you thought you knew about the world

6. North America’s pre-European languages

(via)

This one is particularly amusing given the whole slightly racist, ‘Americans should only speak their original language, English,’ campaign.

7. World consumption of milk

(via)

Two questions: 1) Who took the time to make this map? 2) Wouldn’t the world be a better place if stereotypes were less, “Such and such people are lazy/greedy,” and more, “Man, those Swedes sure love their milk”?

8. How humans spread around the globe

(via)

It’s actually pretty incredible how we spread to every corner of the globe without even knowing what was there, especially in regards to the Pacific Islands.

9. Pirate risk on the high seas

(via)

While I wish this map’s spellchecker had caught the word ‘problmeatic,’ it’s fairly clear what the impact of Somali pirates has been on travel in the Indian Ocean.

10. Population distribution in the United States

(via)

All of this is old information, but I particularly love the illustration of it here, as if population density were topography.

11. The religions of the Middle East

(via)

Sadly, lazy thinking prevails in the United States about the religious breakdown of the Middle East — George W. Bush was rumored to not know about the Sunni/Shi’ite divide before invading Iraq — but this map illustrates that the region is not necessarily monolithically Muslim.

12. Every detected hurricane and cyclone since 1842

(via)

While those of us on America’s Gulf and East Coasts may be sick of hurricanes, we can’t really complain when you look at the sea of white over the Philippines.

13. Every person in San Francisco

(via)

This map is based on the 2010 US census and covers every single person in the city of San Francisco. There’s a similar map of the entire country here. The code is this: Blue dots are white, green dots are black, red dots are Asian, orange dots are Hispanic, and brown dots are all other races.

14. The world’s great rivers

(via)

There’s a zoomable version here, but this map compares the world’s major known rivers as of 1814, with their lengths and the place they flow into at the top.

15. The closest pizza places from anywhere in the United States

(via)

Let’s have a moment of silence for all of the poor bastards whose closest pizza chain is Sbarro.

16. Where people feel the most loved

(via)

Kudos to Hungary, Paraguay, Rwanda, Lebanon, Cyprus, and the Philippines. And if you’re in Mongolia, Uzbekistan, and Kyrgyzstan, start giving out free hugs.

17. What each country leads the world in

(via)

Syria’s having a rough time right now, but at least it leads the world in big falafel balls. A zoomable version is available here.

18. The world’s economic classes by location

(via)

Probably the most amazing thing about this map to me is not the locations of the upper classes — which, to be honest, is totally unsurprising — but that to qualify as having a high level of income, you have to make only $12,196 a year.

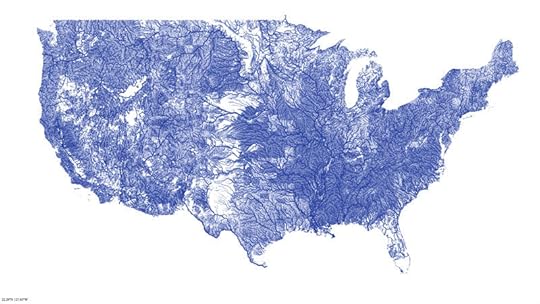

19. America’s rivers

(via)

These are all the rivers in the contiguous 48 states.

20. Which rivers flow into the Mississippi

(via)

7,000 of America’s rivers lead into the Mississippi and from there into the Gulf of Mexico, covering pretty much all of the Midwest but surprisingly little of the South.

21. Indian homes with toilets

(via)

Indoor plumbing is slowly making its way throughout India, unsurprisingly concentrated in the urban centers.

22. China’s invasive passport

(via)

If the disputed territories aren’t on your passport, then you’re not really trying hard enough, are you? Time to put the Falklands on your passport, Argentina.

23. Where the world’s slaves are

(via)

Slavery does still exist around the world. There are an estimated 30 million slaves in the world today — 60,000 in the United States.

24. The world’s economic center of gravity over the past 2,014 years

(via)

This is an absolutely fascinating map, showing how global economic power has shifted over time. You can see specifically that the shift towards Europe was a historically brief moment, that America briefly pulled it in its direction, and then you can watch as Japan and China awake again. It’s also pretty telling that this has been exclusively in the global north and only moved south for the first time in 2,000 years in the last decade.

25. Where the oil comes from and where it goes

(via)

None of this map should be much of a surprise, but it’s interesting to see how much of our oil comes from Venezuela, despite our tense relations with the country.

26. American ancestry by county

(via)

I love that the northern parts of the South are just listed as ‘American’ — as if their ancestry has been lost to time. It’s fun to see some stereotypes confirmed: New York and New Jersey are Italian, the Midwest is German, and Massachusetts is overwhelmingly Irish.

27. Income inequality by country

(via)

While the US stands at about the middle of the pack, it’s incredible which countries are more equitable than we are. You’ll notice Niger, Ethiopia, Egypt, and India all are.

28. The Waterman Butterfly projection

(via)

It’s well known that flat maps generally distort the actual shapes and sizes of the countries (often emphasizing the country or continent of the mapmaker), so some cartographers have attempted to make more accurate flat maps that depict the actual size and shape of things on the globe. Some look like a flattened orange peel, but others look like a pretty butterfly.

29. The world’s navies in the Pacific

(via)

It turns out the world’s largest ocean is still pretty heavily militarized in peacetime.

30. What Africa would look like without colonization

(via)

This one is obviously speculation, but it’s particularly interesting to see just how many more divisions there are from modern-day Africa and how they don’t remotely reflect today’s current borders. The map was constructed based on the tribal and political maps before 1844.

31. A Twitter map of Europe

(via)

Unlike Africa, Europe’s country lines at least make sense. Each of the different colors is a separate language, and it’s a pretty vivid map of what Europe actually does look like. There’s a larger map of the whole world, but it turns out a lot of the world doesn’t tweet.

32. The happiest countries

(via)

For people interested in international travel and happiness, I suggest reading Eric Weiner’s excellent book The Geography of Bliss. And kudos to North America for nailing it.

33. The world’s power outlets

(via)

This one is especially useful for the travelers out there. And while I’m generally anti-imperialist, this is one cultural area which I think Americans should aggressively push on the rest of the world.

34. Annual cigarette consumption

(via)

Holy shit, Russia. We need to start carpet-bombing Moscow with nicotine patches.

35. Child poverty in the developed world

(via)

The US comes in 34th out of the 35 countries ranked.

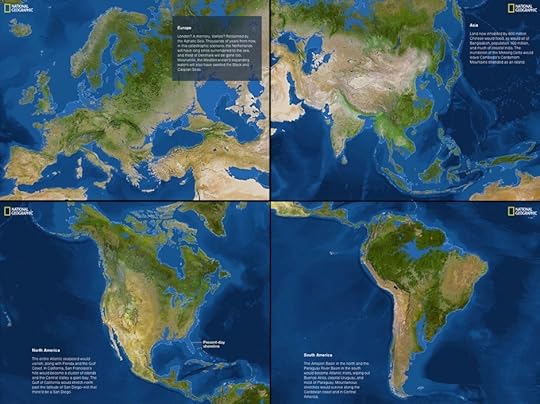

36. When the polar ice caps melt

(via)

We’re finishing off with a pretty sobering one. This is what the world would look like if the polar ice caps melted. Huge numbers of the world’s major cities (along with the entire state of Florida) would be underwater. For the full effect, check out NatGeo’s interactive map.

The post 36 maps that will make you see the world in completely new ways appeared first on Matador Network.

April 13, 2014

10 ideas about evolution

I LEARNED A lot about human evolution while studying anthropology in college. It sucked to enter a jobless market with such an interesting degree, but I still have fun explaining to people how our bone structure has evolved, and why the Paleo Diet is a complete misnomer (our paleolithic ancestors did not eat chocolate chips, or drink almond milk).

Whether or not you agree with evolution, you have to admit, the subject is pretty fascinating, and certainly worth discussing. It’s pretty crazy to see how we got to where we are today, and to imagine how the human race will look one million years from now.

Photo credit: ellenm1

The post 10 ideas that will change the way you think about human evolution appeared first on Matador Network.

In the waters of the Ganges

Photo: Deep Ghosh

One hour before sunrise, the streetlights in Allahabad struggled to break through the heavy fog. Matilda and Amanda, my two Swedish friends, and I stepped out of the rickshaw and into the cold darkness, rubbing our eyes and taking in our new surroundings. Silent shapes wrapped in thick blankets and woolen beanies — pilgrims — floated past us like ghosts.

We were at Kumbh Mela, a major Hindu festival that lasts 55 days and is attended by roughly 100 million pilgrims, making it the largest gathering of people in the world. A temporary city covering an area larger than Athens was set up to accommodate the crowds.

We were there on the Kumbh’s main sacred bathing day. On this single day, 30 million people descended on the Sangam, the confluence of the holy rivers, the Yamuna and the Ganges. Devotees travel from all over India to reach the Sangam, believing that a dip in the holy waters will wash away a lifetime of sins.

We made our way down the misty road with only wan streetlights to light the way. Families walked together, burdened with what seemed to be all their worldly possessions. The smell of chai wafted over to us from the chai wallahs who called out for customers from the side of the road.

As the first grey hints of dawn slowly lit up our surroundings, we could see roads merging with our own. With every convergence our ranks swelled, till the road was teeming with people.

We fell into step with a group of men. “Good morning, sir and madams,” a big bald man bellowed at us. “Welcome to Kumbh Mela! Where are you from?”

“Sweden,” the girls chorused back.

“Have you come specifically for the Kumbh Mela?”

“No, we just happened to be here,” Amanda told him cheerfully. “But we’re very happy we’re here.”

“Oh, well you are so very lucky to be here on this big occasion,” the big man said with a smile. “We have waited our whole lives to come here. We have traveled all the way from Gujarat, and this is a most special day for us. We are happy to share it with you. You must come with us, we will show you the Kumbh Mela.”

We marched on with our newly appointed chaperones and chatted away as their enthusiasm quickly rubbed off on us.

“What religion are you?” the big man called Baba asked me eagerly. When I paused he said, “Are you Christian?” I nodded and said nothing, not knowing how to explain my atheistic tendencies.

I grew up in a Christian household believing in God. By the time I was a teenager, too many questions couldn’t be answered adequately, and too many doubts lingered. So I drifted away. But no matter how disenchanted I grew with the idea of God, I could never fully stamp out the idea of a divine source. I was knocked into that middle place, unable to worship a God in whose existence I could not wholly disbelieve.

We crested a hill as the sun peeked over the horizon. I looked back and saw nothing but people for over a mile. In the distance, I caught a glimpse of the rivers and the Sangam we were headed for. The view spurred the crowd into big cheers and joyous chants for Mother Ganga.

We walked down the hill and into a tented city. Trains of women snaked passed us, each woman holding onto the sari of the woman in front of her. We walked past holy cows, naked sadhus, and families sitting with all their possessions clumped in a big circle. Women knelt praying, their offerings of marigolds floating in the puddles left over from the previous day’s showers.

Our Gujarati guardians began skipping and running towards the confluence. Then, remembering us, they’d stop and call to us to speed up to join them.

As we neared the river the crowd became even more packed together. The throng slowed and stopped. Our guardians pulled us forward, squeezing between people so tightly I could smell the chai on their morning breath. We frantically moved on with our adrenalin surging. We held onto each other and shouted encouragement to keep going. Then, suddenly, we stepped through a line of people and found ourselves on the banks of the river.

Photo: cishore™

The Gujarati men quickly undressed to their underwear and hurried into the water. Matilda and Amanda stayed and watched our belongings while I followed Baba into the river. The men splashed around, shouting and laughing with each other. We dunked our heads under the water, once for ourselves and once for each of our family members.

While the men took their prayers, I strode further out into the river and looked back. All along the banks, men and women made blessings and prayers. People collected water from the river in old plastic milk bottles. The scent of burning incense wafted over from the shore. Indians were climbing over each other to reach the river; there were people swarming everywhere for as far as I could see. Overloaded boats and wooden canoes drifted by on the river.

Near to me in the water, I saw an old frail woman with a gold nose ring dressed in a pink sari. With her eyes closed she faced the rising sun, cupping her hands aloft as the water spilled out of them. Her face had a look of divine rapture. I found myself looking on in wonder, and with a sense of longing.

I felt distant and alien; I yearned to find something I could believe in. I needed something to fill the hollow spaces at the bottom of each of my breaths.

I dipped my head under the water and hoped that Mother Ganges would wash away not only my sins but also my incessant questions. I wanted relief from my persistent doubts and my resilient despair. I wanted to clear my mind and be carried away, to float down the river, still and thoughtless as a leaf.

The post Kumbh Mela: What I found in the waters of the Ganges appeared first on Matador Network.

April 12, 2014

Cool country superlatives

THIS VIDEO HAS provided me with enough fodder to get through even the driest of cocktail party conversations. From knowing which three countries make up almost half of the world’s population density, to the highest and lowest homicide rates per country, I will never be at a loss for impressing other people with some pretty interesting global knowledge. I hope I win some free drinks at trivia as a result as well.

The post Impress your friends with these cool geography superlatives appeared first on Matador Network.

10 useful German phrases

Photo: Spreng Ben

“It’s sausage to me,” and other extraordinarily useful German phrases.

MY FIRST TRIP TO GERMANY was courtesy of my law school, which gave me the opportunity to apply for a summer job in Hamburg. My undergraduate degrees were in Music and German, and I’d always thought I’d get a job singing in Germany. But I was in law school, so I took the law job. As it turns out, reading Schiller’s plays and singing Goethe’s poems doesn’t actually make you fluent in contemporary German. Here are a few of the useful words and phrases I didn’t learn in college.

1. das ist Bescheuert — “that’s ridiculous”

das ist beshoyert — /dɑs ɪst bɛʃɔʏɘɾt/

Bescheuert is usually translated as “crazy” or “stupid,” but it seems to be the catchall word for “bad.” Das ist bescheuert is the equivalent of “that sucks.” You got stood up? Das ist bescheuert. The U-Bahn was late? Das ist bescheuert. Whatever it is, if you don’t like it, it’s bescheuert.

2. na? — “so…?”

naa — /na:/

People who know each other well say na? to ask “how’re you doing?” It’s also used when the topic is understood and the speaker is inquiring how something turned out. For example, saying it to someone who had a big date the previous evening means, “So how’d it go? I want details!” This is not to be confused with na und? (“so and?”), which means “so what?” or “what’s your point?”

3. das ist mir Wurst — “what do I care?”

das ist meer voorsht — /das ɪst mir vurʃt/

A bit more emphatic than das ist mir egal (“I don’t care”), das ist mir Wurst (literally, “it’s sausage to me”) means, “I don’t care, it’s all the same to me,” or even, “I couldn’t care less.”

4. Ich besorge das Bier — “I’ll get the beer”

eeh bezorge das beer — /ɨx bɛzɔrgɘ das bir/

Besorgen means “to take care of,” and it’s used informally to mean “get something” or “pay for something.” Ich besorge das Bier is useful at Oktoberfest or any gathering with kiosks selling refreshments. After you say Ich besorge das Bier, your friend will probably offer to get the food. And when she asks whether you want Bratwurst or Knackwurst, you can answer, Das ist mir Wurst. You’re now punning in German!

More like this: 9 ridiculously useful Spanish expressions

5. kein Schwein war da — “nobody was there”

kayn shvayn var da — /kaɪn ʃvaɪn var da/

The word Schwein (“pig”) is possibly the most used word in the German language. You can attach it to almost anything. Sometimes it’s a noun by itself, as in kein Schwein war da (“nobody was there”), or kein Schwein hat mir geholfen (“not a single person helped me”), but it can also be added to nouns to make new words.

Eine Schweinearbeit is a tough job. Something that kostet ein Schweinegelt is ridiculously expensive. If you call someone a Schwein, that’s as insulting as it is in English. But if someone is an armes Schwein (“poor pig”), he is a person you feel sorry for. And most confusing of all, Schwein haben (“to have pig”) means to be lucky!

6. der spinnt — “he’s nuts”

dayr shpint — /der ʃpɪnt/

The verb spinnen originally meant (and can still mean) “to spin,” as in spinning yarn at a wheel. But in contemporary German, spinnen is more often used as “to be crazy.” This usage may have derived from the fact that in previous centuries inmates in mental asylums were taught to spin yarn. Saying der spinnt is often accompanied by the hand gesture of moving the palm side to side in front of the face. In fact, sometimes you’ll just see the hand gesture.

7. langsam langsam — “little by little”

langzam langzam — /laŋzam laŋzam/

Langsam means slow or slowly, so you might think that repeating it would mean “very slowly,” but langsam langsam is the expression for “little by little” or “step by step.” It’s a good noncommittal answer to, “How’s your German coming along?”

8. das kannst du deiner Oma erzählen — “tell it to your Grandmother”

das kanst doo dayner ohmah airtsaylen — /das kanst du daɪnər oma ertseːlɘn/

Das kannst du deiner Oma erzählen is the response to an unbelievable claim. For example, “I’m studying German three hours a day. I’ll be fluent in a week.” “Oh yeah? Das kannst du deiner Oma erzählen!”

9. nul acht funfzehn (0-8-15) — “standard issue / mediocre”

nool acht foonftsayn — /nul ɒxt fʊnftsen/

The standard issue issue rifle in WWI was a 0-8-15. The term caught on and is now used as a classy insult. I first heard this phrase from a friend describing a less than memorable sexual encounter. When she described it as nul-acht-funfzehn, I thought she was talking about some obscure sexual position. What she was actually saying was, “meh.”

10. Ich habe die Nase voll davon — “I’m sick of it”

eeh habe dee naze fol dafun — /ɨx habə di nazə fɔl dafɔn/

Ich habe die Nase voll davon literally means, “I have the nose full,” which really means to be sick of something or someone. As in, “enough already, Ich habe die Nase voll von German phrases.”

This post was originally published on December 21, 2011.

The post 10 extraordinarily useful German phrases appeared first on Matador Network.

Matador Network's Blog

- Matador Network's profile

- 6 followers