Matador Network's Blog, page 2234

August 1, 2014

World Cup winners give back

Photo: Sama093

The World Cup is over, and it was pretty rough on Brazil. Not only did their national team face what was almost certainly its most embarrassing defeat in history, but the event was marred by protests, and the country is now saddled with a number of stadiums in places that don’t have teams big enough to support them.

The good news is that, even though FIFA pretty much just leaves a path of destruction wherever they go, the soccer players don’t. Mesut Özil, a midfielder for the victorious German team, is donating part of the 300,000 euro bonus he received for winning the World Cup to pay for surgeries for 23 Brazilian children.

Özil isn’t the only footballer to donate World Cup winnings to charitable causes. The Argentine team, which came in second place, is donating $135,000 to a pediatric hospital in Buenos Aires through Argentine star Lionel Messi’s charity. Messi, who won the Golden Ball in the 2014 World Cup (given to the tournament’s best player), has supported the hospital in the past.

So if there are any Americans out there who are now hooked on soccer thanks to the 2014 World Cup and are looking for European teams to support, here’s a good start: Özil plays for Arsenal in England, and Messi plays for Barcelona.

Atlanta: A city too busy to hate

GROWING UP ON THE OUTSKIRTS of Atlanta, I felt out of place, a stranger in my sterile suburban surroundings. As an adult, I seek to understand the place I still call home even after moving 2,173 miles away to Los Angeles.

I’ve found that Atlanta is in many ways defined by a past marred with racial tension and a craving for rapid development and progress. Atlanta’s history is one of urban expansion, systematic institutional segregation, and white suburban migration, with an underlying and long-standing political structure controlled by a coalition of wealthy executives and upper-middle-class African Americans — hindering the advancement of the lower class-black community.

Despite all this, the city is also looked at as a role model for the South, as a bastion of racial equality and civil progress. The city’s current identity is defined by a stew of race, success, vanity, poverty, and glamour, mixed with a slew of contradictions. This current landscape is far different from Atlanta’s birth during Reconstruction as the industrial capital of the South and subsequent rebirth as a Civil Rights stronghold and home of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Even today, the city is looked at as a black Mecca and, dubbed “the city too busy to hate” in the 1960s, continues to raze low-income housing, eliminating entire neighborhoods within the city for the sake of international status symbols like the numerous sporting complexes and the ill-advised rapid transit system, leaving empty promises of redemption for former residents in the wake.

The city’s newest incarnation as the hip-hop capital of the South has thrust Atlanta back into the spotlight and created a new, unique, and prevailing subculture while bringing in over $1 billion in state revenue each year. Home to countless hip-hop artists and famed recording studios, including So So Def, Stankonia, PatchWerk, and more, the city also hosts the BET Hip Hop Awards, the Dirty South Awards, and the Trumpet Awards. Atlanta’s mayor, Kasim Reed, has also paved the way for the film industry to continue to prosper and grow in the city’s already burgeoning industry through appealing incentives. Strongholds like Tyler Perry Studios, The CW, and Turner continue to thrive, as the promise of more sits just on the horizon.

In a country where the demographics sit at 13% Black, Atlanta’s 54% Black population makes this sociological study, based on the outline above, even more relevant and important to document. Put simply, I seek to explore Atlanta’s past through reflection on the present.

“Too Busy To Hate” is a photographic sociological study of the cultural identity of the capital of the South.

1

The Seed & Feed Marching Abominable struts down Peachtree Street in the heart of downtown Atlanta during the annual Georgia Veteran's Day Parade.

2

1017 Brick Squad producer South Side near the Georgia Dome in downtown Atlanta.

3

Nick Barrows on the side of Memorial Ave. in Atlanta's Grant Park neighborhood. Barrows, a Boston native, came to Atlanta for a friend's birthday and never left. "Atlanta just wouldn't let go of me," said Barrows.

Intermission

6

10 signs you were born and raised in Atlanta

by Caroline Eubanks

Unearthing the temple: Portraits of the Mazahua and Mixteca at Mexico City’s Templo Mayor

by Kevin Garrison

3

8 signs you’re still a tourist in Naples, Italy

by Vicki Jones

4

A young girl watches television in the bedroom at a loft party in Atlanta's Castleberry Hill arts district.

5

Reflections of Martin Luther King, Jr. in a storefront window in downtown Atlanta.

6

Tapp Out Billiards near the I-75/85 connector in downtown Atlanta.

7

Former World Heavyweight Champion boxer Evander Holyfield trains at the AD Williams Recreation Center on the west side of downtown Atlanta.

8

Students on the volleyball team practice in the school gym at Atlanta International School.

9

Extras prepare for a birthday party scene between takes on the set of The Vampire Diaries in a studio warehouse in Atlanta.

Intermission

1

9 things you’ll miss after leaving Charleston, SC

by Caroline Davidson

4

The Rastafarians of St. Thomas, Jamaica [pics]

by Kevin Garrison

4

25 things you need to know about Georgia

by Jeremy Jones

10

A car rolls down historic Sweet Auburn Avenue during Atlanta's first annual Black History Month Parade in downtown Atlanta.

11

Soulja Boy and Lil Jon on the set of the Soulja Boy music video for "Gucci Bandana."

12

A crowd gathers around iScream, Giedrius Gatautis' ice cream truck company, at one of the pools on his route in Marietta.

13

1017 Brick Squad producer South Side gets a new hand tattoo from Brick Squad Ink tattoo artist Kintoz inside PatchWerk Recording Studios in downtown Atlanta.

14

Sunday morning worship at the historic Big Bethel AME in downtown Atlanta.

15

Dialysis patients, mostly undocumented immigrants, who were dislocated by Grady Memorial Hospital's decision to close its outpatient dialysis unit, gathered for a meeting at Oakhurst Presbyterian Church Sunday.

Intermission

4

11 portraits that reveal the real faces of the homeless

by Joshua Thaisen

2

These are the faces of people I met in Haiti

by Katherine LaGrave

4

10 powerful portraits from the Ecuadorian Amazon

by Alex Goff

16

Janelle Monae sings the song "Cindi" at Wondaland Arts Society in Atlanta.

17

Models pose on the Cycledelix Ryders display booth at the V-103 Car & Bike Show at the Georgia World Congress Center in downtown Atlanta.

18

Models pose on stage as part of the Christmas display at Atlantic Station, a planned shopping and housing community in downtown Atlanta.

19

Monica, aka Honey, performs at the Blue Flame strip club in South Atlanta.

20

Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed in his office inside of City Hall in downtown Atlanta.

July 31, 2014

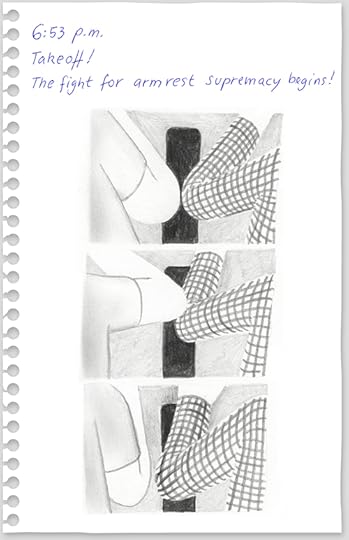

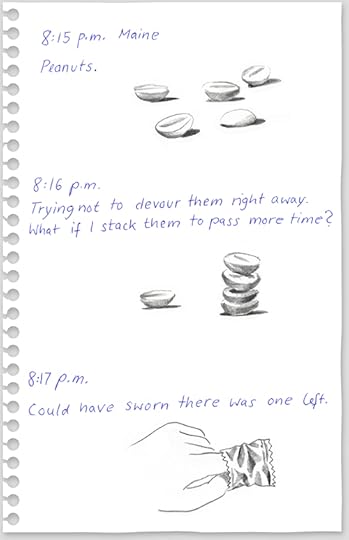

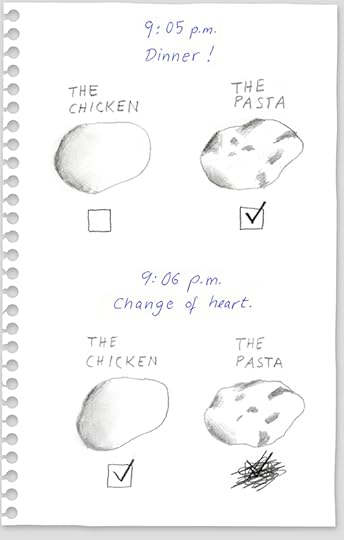

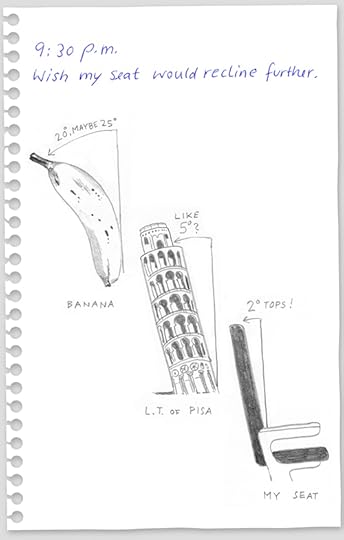

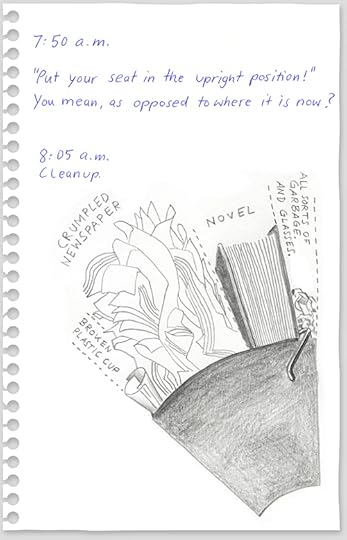

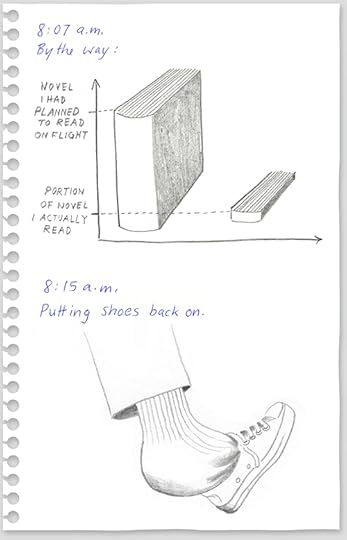

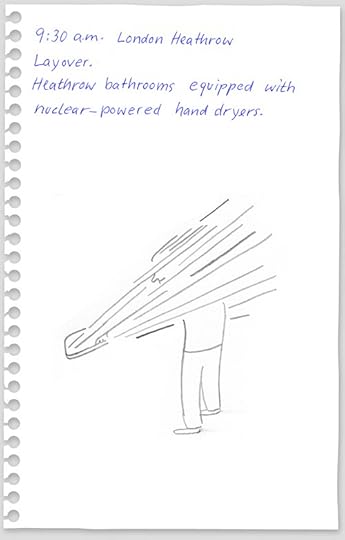

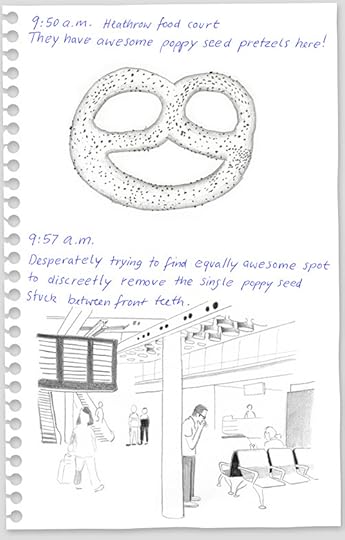

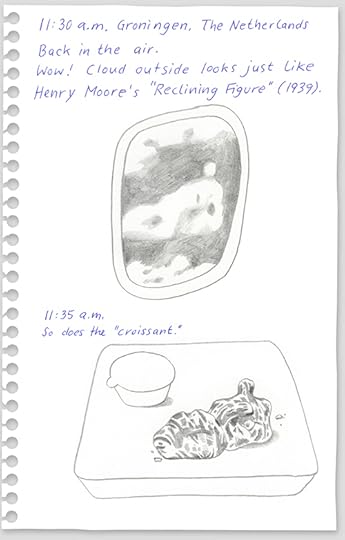

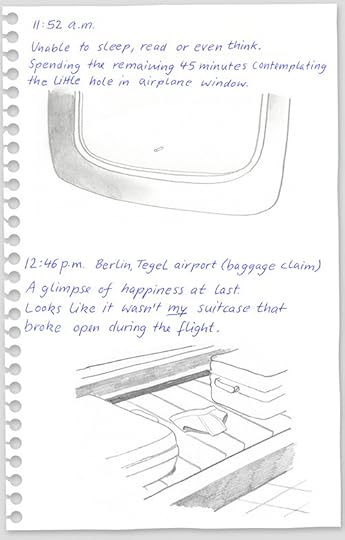

An illustrated guide to flight

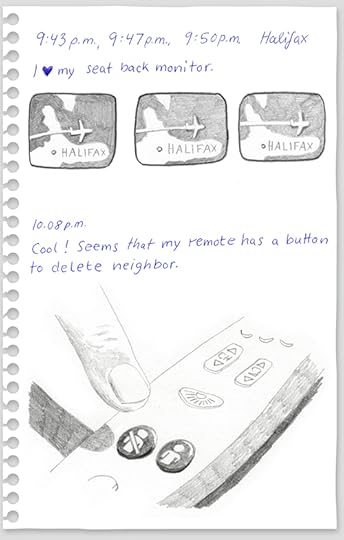

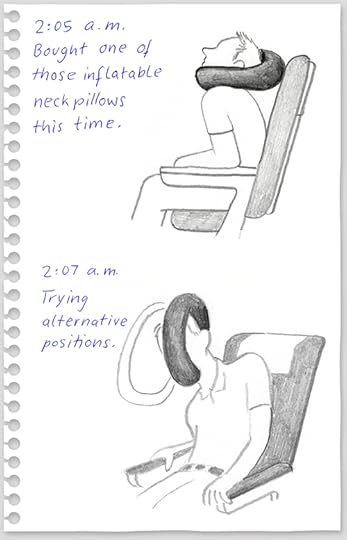

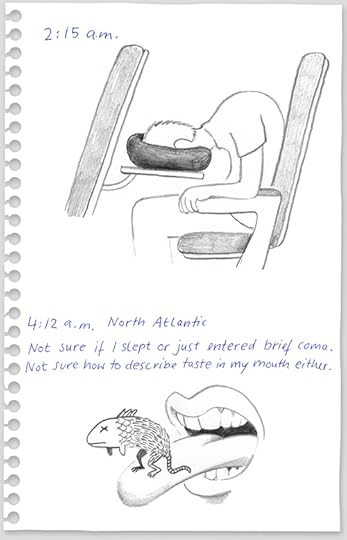

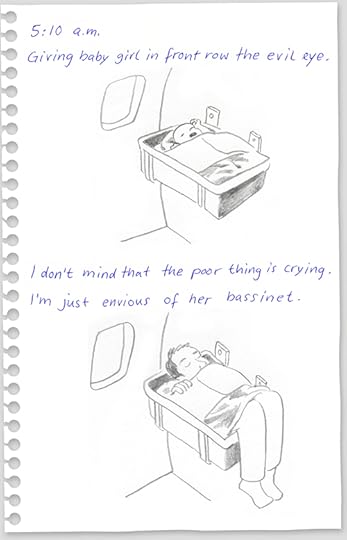

I RECENTLY BEGAN sketching during long-haul flights. It helps distract me when I feel anxious, and usually I’m pretty drunk during takeoff, so the things I produce in my journal are hilarious. But they can’t compare to the drawings of Christoph Niemann, who 100% captures what goes on in the minds of every single person who has ever flown from the East Coast of the USA, to Europe and beyond.

My favorite part is the progression of the seat back monitor. Spot on.

How to be home

Photo: Bill Dickinson

THE WEIGHT OF THE DECISION to leave a home is often overshadowed by the logistics of the move itself, so much so that we forget about the courage it really does take. No matter your reason for starting a new chapter in a new place, once the luggage is sorted and the tickets are confirmed, only then do we feel the full force of the stamina required to take this risk, the spirit to not be disappointed with what we encounter, and the nerve to not long for what we left behind.

Some days it pours from the moment I wake up. They say this weather can extend for months in my corner of East Asia. Breathing in those last few moments of unconscious twilight, the rain slapping the tin overhang could just as well be the rhythmic, steady click-click-click of drizzle coating the air conditioning unit balanced out the window of my old apartment halfway around the world. But I’ve been away for long enough to know that it is not. And I’ve been away for long enough to know that on some days, just some, the thrill and deliciousness of navigating this newness, this confusion, this excitement I’ve sought out will be, well, damp.

These are the days I miss my last home. The trusty dependability of it all, the level of control I felt, its predictability. I feel exposed navigating this city that’s now supposed to be my own: “Hey, look, her expat is showing!” But having the courage to get up and go was just the beginning. It takes an ongoing emotional toll to keep from romanticizing our past lives too much, to let go of the places we craved to leave.

Largely, no matter where you go, you’re leaving behind a dependable life brimming with dependable people on dependable schedules. I boasted a steady income and a gorgeous apartment and friends who each have kept a piece of my heart. But I stirred, kept awake at night by an unidentifiable monotony, a certainty that I was not in the right place and a faith in somewhere I hadn’t even been yet. I’d fight sleep, suffocating on the fear that when I woke up it would be an identical day, five years later.

So I left. I left stability, familiarity. I left people who meant everything to me. I left the bartender who had my drink served up by the time I took my seat. I left my local lunch haunt, where they always added on extra avocado. I left rooftop conversations of equally poured portions of incredible importance and inconsequence, feet dangling over the edge as I gazed out on the Empire State Building with a friend-turned-roommate-turned-sister. I left fresh bagels.

We’ve all left home.

But New York City wasn’t always home. Once, home was the front lawn in a college town, speakers resting on an upended beer-pong table blasting the playlist that still brings me back to that rundown house, worn from years of kegs dragged across its threshold and strangers sleeping on the floor. Home was one-liter boxes of wine and cigarettes littered across a riverbank, the Andalucían accent and wafts of Moroccan hookah cutting the breeze as I napped in the afternoon sun. It was the living room couch of an apartment with no lock to the front door, where I once was in love. It was the basement of my high school best friend when we were moody teenagers with so much time and beauty ahead of us, ignorant to all the magnificent heartbreak and adventure we would face and overcome, still free from the steady decay of cynicism.

Home will be new street corners and train cars and dimly lit bars. It will be midday G-Chats with friends dotted across continents and handwritten letters addressed to bars, because you know that as friends’ zip codes change, their preferences don’t. It will be rooftops overlooking a new city, and the moment of silence you breathe in before these new people you love, your new family, tear up the stairs, an evening’s supply of booze in tow. It will be places revisited, homes we’ll take up for a second go. It will be the carefully mapped itinerary tackled with the person who shares your dream.

Home is laughter at communication faux pas on humid train station platforms. Home is fireworks shot off in the streets and hopelessly misunderstood directions and breakfasts of burnt eggs and toast at three in the afternoon.

Home is the people who remind you of who you are.

When we each got on that airplane, packed up that car, departed that city — we shouldered the mystery of a foreign film with no subtitles. Captivation heightened, we couldn’t help but be entranced and confused but breathless as our story unfolded rather nonsensically and unpredictably. We’re charmed by the uncertainty, the difficulty — we explain ourselves to no one. But as our story arcs rise and fall, climaxes test our wherewithal to see this storyline out.

Maybe we should have stuck with something more familiar after all, a film we already had at home, even if we leafed through that collection a dozen times and found nothing we wanted to see.

And then suddenly the story makes all the sense in the world. Our narrative continues whether we’re prepared for it or not; it doesn’t wait for us to understand. We just hadn’t seen the plot growing while having grown scared, surreptitiously intent on reciting old scripts.

Because we can shift all across this planet, chase new experiences, and take control of our own story, but at its core, our narrative only shifts so much. Every day we smile, plan, pursue our dreams. We drink too much, lose sleep, we turn off our phones and tune the world out to bad Netflix movies. We worry, we risk, we take the harrowing, damning chances to give all of ourselves to everything we do, to everyone we love, regardless of what we get in return. Every day we’re home.

This post originally appeared at Thought Catalog and is republished here with permission.

Life as an ESL student in Ireland

Photo: Learn English at DCU

1. You will be welcomed.

You’ll touch down in Dublin, ready to begin your ESL course. The airport is a very clean and safe place, and it will seem comfortable enough to stay here eating O’Donnells “Irish cider vinegar and sea salt” crisps and drinking Dr. Pepper for a while. When you do leave, you’ll hop on a Citilink bus to Galway in the west, and all the way you’ll smile and laugh at the jokes the skinny, white-haired, talkative bus driver named Bill tells. After three hours of looking through the window and watching the green lands overcrowded with sheep and cows, you’ll arrive in the city where you’ll live for the next month or so learning English. You’ll be a bit nervous, but the cool wind will welcome you with open arms.

In the taxi, you’ll share a few clichéd words with the driver in your still-primitive English. But mostly you’ll be looking out the window, noticing the vibe of the streets, where dozens of girls wearing flashy, tiny skirts and pale boys with tattooed arms are searching for the perfect pub to spend the night. Finally you’ll arrive at your new home, and you’ll meet the host family you’re going to live with. They’ll say to you with happy words: “Welcome to Ireland!”

2. Multiculturalism will surround you.

The English school where you’ll attend English classes five days a week will be like a unique world of its own. You’ll make friends with people from Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Switzerland, Germany, Belgium, France, Spain, Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, and more. You’ll forget about your native language and speak English as much as possible, because no one in the school will look at you funny if you make a grammar or pronunciation mistake.

Outside of school, though, it’ll be different. You’ll try to sharpen your ears because people on the street — Irish mostly, but also North Americans, Canadians, and Indians — will talk to you in a faster pace than your English teachers, Colin and Aisling.

3. You’ll struggle with the Irish accent.

Once you get the English of the Irish, you won’t have to worry about any other English accent. At school, you’ll practice with many accents to be ready for the listening exam, but none of them will be comparable to the English you hear on the streets of Ireland. It’ll be difficult to understand because they speak very fast and load their words with humor and irony.

So you’ll spend a day as a tourist with an Irish guide on a walking tour, and you’ll build even more confidence with your Irish-English listening skills. In the middle of a historical explanation, you’ll ask Molly, the Aussie girl beside you, “Sorry, but do you understand everything he says?”

She’ll look pissed off at your stupid question and say, “Geez, I’m trying to.”

4. The best places to learn will be in the pubs and street markets.

You’ll find that the best places to study language are the pubs and bars where, on rainy days, the music and beers never end, and the colorful street markets and public squares where people relax during warm days.

You’ll find that Irish people love to speak and laugh. They’ll tell you stories and show interest in hearing yours in return. In every pub, you’ll be surrounded by good drinkers and funny companions. You’ll decide to take it easy and be authentic, because as the Irish say, “God created time. And then he gave the Irish a little more.”

5. The scenery of Ireland will move you.

You’ll plan your weekends wisely and travel all around the country. You’ll go north and visit Ballycastle in County Antrim, where you’ll find astonishing landscapes and walk across a 25m rope bridge across the sea to the cliffs of small rocky islands.

You’ll visit the Giant’s Causeway and walk over some of the 40,000 geometrical basalt columns and immerse yourself in the legend of the site. You’ll imagine, for just a moment, that you’re Finn McCool, the giant who built the road to be able to cross the sea and share time with his giant lady.

You’ll go west, take a ferry near Galway City, and be impressed with the landscape of the Aran Islands, where you’ll buy a fabulous sweater and try to speak with the locals to hear some of the Gaelic language.

You’ll visit the Cliffs of Moher and enjoy the sights of the 200m vertical walls of rock where puffins live. You’ll be amazed by the greatness of the Atlantic Ocean that stretches out to the horizon.

And finally, you’ll go east, where the beautiful forests of the Wicklow Mountains cover the valleys.

6. You’ll become a master of beer and whiskey.

A good thing about Ireland is that no one considers you crazy if you drink a Guinness at 11am instead of a cappuccino. Beers are an institution here. Blonde, red, or black, it doesn’t matter what your preferences are — between Guinness, Beamish, Murphy’s, Kilkenny, and Smithwick’s, the whole beer spectrum is covered.

You’ll remember watching Jimmy McNulty in The Wire drinking Jameson whiskey and singing Irish songs. Ireland will come to life and there you’ll be, walking into Temple Bar just two hours after arriving in Dublin. You’ll order a shot of Jameson in the crowded cantine that you found, and it will be so marvelous that you’ll go back to that same place for another one after finishing the English speaking exam.

7. Life will be sunnier after Ireland.

The weather will be bad. Dark days and showers. The wind will be so strong there will be no point in carrying an umbrella. But when a sunny day in Ireland does hit, you’ll never be happier.

The pro skateboarder with no legs

LAST WEEK, I skateboarded for the first time in about 12 years. My town just opened up a brand new skatepark and I’ve been dying to try it out for months. I grew up skating in the 80s; I stopped when I was 16 or so, then picked it up again for a short time in my mid-20s. It’s something that has never left me, and I don’t think it will.

I’m 38 and am a little self-conscious, because sometimes I feel like this is something for the kids. But I’m slowly getting over that and just having fun doing it again.

When I see the Bones Brigade (my childhood heroes) still going, I get inspired. This, however, inspires me even more.

Meet Italo Romano. He lost his legs as a teenager in a train accident. But that hasn’t stopped him from becoming a pro skateboarder.

Think I’ll go hit the park.

Jewish doula, Palestinian baby

Photo: Jlhopgood

One midday in July of 2000, in Hospital Meir in Kfar Saba, a Palestinian boy was born before my eyes.

When I entered room #5, I met Fatma and Ali. I asked if I could stay to help as a doula. Ali said yes, that anything I could to help his wife lessen the pain would be welcome. So I stayed as a kind of physical therapist.

Fatma didn’t answer, not because she couldn’t say anything, but because she only spoke Arabic. Ali spoke perfect Hebrew and this way we could communicate. When I needed to work with Fatma, the only communication possible was through her looks, her sense of feel, breathing, the perceptions of anguish, pain, and whatever lessened the pain. Fatma’s eyes were glued to mine from the time she hugged me until the time she let go. Ali was doing the best he could, and I wanted him to feel that he was helping her. The most important thing was that Fatma felt supported.

Just a few moments before his son was born, Ali told me that Fatma was 33. They had been married 18 years, and this was their first son. Although Fatma had had seven pregnancies, five ended in miscarriages. And yet, despite the doubts that the doctors had about a healthy birth, there was this feeling — you could sense Fatma’s determination — that she was going to bring this child into the world alive no matter what.

During the last few contractions, Ali on one side and I on the other, we gave Fatma a single big hug to give her strength. And then there was a chanting that reverberated through the hall — Allahu Akbar. Fatma received her child on her breast. She kept repeating Allahu Akbar as she nursed the baby.

Ali and I collapsed into a hug, giving into a cry of emotion, brotherhood, and pain. Afterwards, all three of us hugged. I don’t know how long this hug lasted, but I can still feel Fatma’s and Ali’s tears falling together with mine.

After two hours, when everything indicated a successful post-partum, Fatma left with her baby to a room where they’d stay two more days. I gave Ali a final hug. His words still sound in my ears: “Todá ahjí. La Salaam Aleikum,” a mix of Hebrew and Arabic. I answered “Aleikum Salaam,” peace to you. I never saw them again.

Back at home, in one of the most treasured days of my life, I thought: What a shame there weren’t TV cameras, international journalists, and political pundits bearing witness to that moment. Perhaps then they could’ve captured that hatred between people doesn’t have to exist. When we have the opportunity to treat each other with respect and love, the people always win.

Since this time I’ve attended other births of Palestinians and Arabs and accompanied various others in this same hospital, but this was the most symbolic. We’re not born enemies, we’re simply people. Nothing more, and nothing less than people.

10 signs you're from Kansas City

Photo: kirybabe

1. You’re fiercely loyal to local ‘que and know your way around a grill.

Whether you claim allegiance to BBQ powerhouses Gates and Jack Stack, Missouri-side Arthur Bryant’s, Kansas-side Oklahoma Joe’s, or (my favorite) small-fry LC’s, you think of them when anyone mentions barbecue. Roll out the smoker and soak those wood chips — hot dogs and hamburgers just won’t cut it.

2. You’ve grown accustomed to crappy sports teams.

KC sports fans can’t catch a break. Anyone will tell you when we last won the big one: 1985. We beat our cross-state baseball rivals in what was dubbed the I-70 Series. But the Royals, god love them, haven’t made it to the postseason since.

And the Chiefs, who were competitive in the heady days of the early NFL and flirted with postseason success in recent years, have had an even longer drought. We won Super Bowl IV, more than four decades ago. Len Dawson, quarterback for our one Super Bowl win against the Vikings in 1969, covers sports for Channel 9 and still calls games on 101 The Fox — we’re all secretly hoping we can pull one out before he retires.

3. You know the Timberwolf is the most terrifying rollercoaster in the world.

It’s made of wood and goes way faster than any wooden machine should, jostling you around on the way up the big hill and rattling your teeth in your skull on the way down. You start to understand why people thought Model Ts would kill everyone. When not safely enveloped in plastic, steel, and fiberglass, anything that goes faster than 10mph feels like a death trap.

4. You’ve downed a Skyscraper Soda…and lived to tell about it.

Winstead’s — KC’s diner staple decked in ’40s pinks and blue-greens with chrome finishings — makes the Skyscraper Soda in a GIANT GLASS VASE. Piled high with vanilla and chocolate ice cream and topped off with soda, it’s practically a rite of childhood to split one with your siblings/cousins/neighbors, dueling with long-handled diner spoons and jockeying for position with the doubled-up long straws so you can gorge yourself until you want to puke.

5. You have a picture of you with the giant shuttlecocks.

Yes: 20ft-high replicas of white-feathered shuttlecocks dot the lawn of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. It’s said that the sculptors were drawn to feathers because of the local Native American heritage, but designed the shuttlecocks because from above, the museum grounds resemble a badminton lawn. Everyone has a picture of themselves next to one, behind one, even jumping in front of one. They’re a magnet for area brides, so during the summer watch out or you could photobomb a wedding party.

6. You’ve got nothing but love for the City of Fountains.

We’ve got more fountains per square mile than any city in the country and are second in the world only to Rome (so they say). After all, the Romans invented the Aqueduct, so we’ll let them take the top spot.

Clockwise from bottom left: Jazz Guy, Heidi Elliot, Adam

7. You know which Kansas City you’re from.

Most people in the Midwest know there are “two” Kansas Cities but lump them together as one. In KC itself, clear distinctions are made across State Line: 816 in Missouri and 913 in Kansas. But break it down further and you’ve got KCK, Johnson County, North Kansas City, Kansas City North, Brookside, Westport, Crossroads, Power & Light, 18th & Vine…the list goes on.

8. Every Thanksgiving, your family drags you out in the freezing cold to see the Plaza Lighting Ceremony.

Most people start the day watching a well-orchestrated stream of cartoon balloons, small-town marching bands, and teen dance squads parade down wide city avenues while preparing a traditional meal for sharing with family and friends. In Kansas City, though — after everyone has slept off the first in a season of excesses — we pile into the car and drive down to the plaza to jostle for a spot to see a local celebrity (Paul Rudd, Jason Sudeikis, and Kate Spade have all done the honors) flip the switch and light up the skyline.

9. You can hum the concession stand’s theme music at the I-70 drive-in.

One of the largest drive-in theaters still in operation, the I-70 drive-in’s neon arch marquee echoes its sister arch in St. Louis, announcing the four double features playing. Every screen plays the same vintage concession ads, with absurd dancing hot dogs, candy, and popcorn boxes that play on a loop with a minute countdown so you don’t miss any of the late-night feature.

10. You cringe when people say, “We’re not in Kansas anymore,” but you can’t imagine calling anywhere else home.

Dorothy knew exactly where she wanted to be and you can’t blame her. Fats Domino, Okkervil River, Van Morrison, even the Beatles sing about coming here. You might take a plane, you may take a train, but if you have to walk, you’re going just the same. Kansas City, here you come.

Anchovies are awesome [vid]

ANCHOVIES GET A BAD RAP as a pizza topping thanks to their general saltiness and ickiness — unless you’re Dr. Zoidberg — so maybe we should start appreciating them more as actual living things.

Take this video, for example, made by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego. It shows a massive school of anchovies near Scripps Pier in La Jolla, California, and it’s captivating. The motion of the fish as a school is otherworldly from above, fluid and graceful from underwater (which you can see by jumping to the 1:45 mark on this video).

Their incredible schooling patterns aside, anchovies are actually among the most sustainable fish you can eat. This is because they’re small, numerous, and on the bottom of the food chain, which means their removal from the ecosystem has less of an impact on the surrounding environment.

15 portraits of travel relationships

Editor’s note: One of the first lessons you can learn about traveling is that the people you spend your time with are even more important than the destination itself. Think of how a good friend can make hours on a cramped bus feel like minutes, while a constant complainer can turn a trip to even the chillest of places into a chore.

These 15 portraits and stories, sourced from the community at MatadorU, are of relationships that, for at least one traveler, felt as iconic as any landmark and had the ability to define an entire country and journey.

1

This was shot at Khalsa College, Amritsar. I was visiting the building as part of my architecture school's field trip, but instead of clicking the grand college so often confused with a palace, I noticed this old man cocooned in his blanket at the entrance. As I started having a conversation with him, he told me he has been the watchman of the college for more than 70 years. He was just a young boy when he took up his post, and had the most interesting stories to tell. He described in detail how he saw the young princes and princesses attend college in horse-drawn carriages during the British Raj.

Photo: Sarthak Chand

2

Cassandra O'Leary

Let’s face it, having kids is an adventure in itself, but traveling with them is like getting a second chance to see the world through innocent eyes full of wonder. Looking at this photograph of my son brings back many happy memories. In his smile I see the joy in the simple act of traveling, the feeling of freedom, and the openness to explore.

Traveling has always been a part of my life, and now it is a big part of my children’s lives too. There is no better (or more enjoyable) education than travel, and I look forward to exploring with my kids by my side.

Photo: Cassandra O'Leary

3

This is Mohammad. The 32-year-old Jordanian guide spent ten days with me and a team of fellow photographers as we explored Jordan and volunteered with The Giving Lens. He is amazing. He shared his passion for his country and culture so well that we all fell in love with Jordan. He is the perfect illustration that, like he told us, “Life is not about material things. Life is about relationships.” Then, at the end of the trip, he added: “No matter where you go, remember that you now have family in Jordan.”

Photo: Sebastien Beun

Intermission

20

15 signs you were born and raised in Melbourne

by Paul Kucewicz

6

24 hours at the world’s largest camel fair: Pushkar, India

by Kate Siobhan Mulligan

4

25 things you need to know about Georgia

by Jeremy Jones

4

This was taken in Shantiniketan during Durga Puja. I didn’t feel wholly comfortable capturing this image at first. It felt like a ‘Poverty porn’ shot. Soon after, I realized the scenario. The boy was looking at us and we, all dressed in brand new clothes, were enjoying the festival.

Photo: Aveek Mondal

5

I met this little girl when I visited Bali, Indonesia. I was visiting the Besakih Temple near Ubud and, as usual, I came across many people who wanted to sell numerous things to me. But this little girl was probably the most persistent salesperson I have ever come across. She did not budge, spoke perfect English, and had solutions to all my reasons (or rather, my excuses) for not buying. After I told her “I do not have small change,” her reply was, "Oh! That's not even a problem. I have all the change in this world." The most amazing thing is that she was only 7. Woah!

Photo: Arpit Malik

6

I met Abdullah on my way to a mosque in the city of Van in Eastern Turkey. He couldn't speak a word of English and I could only say “hello” and count to ten in Turkish. After a brief chat in the international language of hands, we went to an internet cafe and used Google Translate to continue the conversation. I learned a lot about the city and made a new friend in one of the most culturally rich places on Earth.

Abdullah and I still keep in touch, and although communicating via Translate is difficult, there is one Turkish word I learned the meaning of: kardeşler, brothers.

Photo: Javed Adam

7

May is one of the tour guides that I met in Sa Pa, Vietnam. We sat next to each other in the van on our way back to the hotel after a day trekking in the rice terraces. She's from the Black H'mong tribe. The people from this tribe wear black, but May told me that sometimes she wishes she could wear another tribe's clothing, clothing that wouldn’t take a whole 20 minutes just to put on.

Most of the women in the Black H'mong tribe marry in their late teens. May, who is only 18, is single. She told me she’d rather marry in her late 20s, as she wants to make the most out of her youth. The reason why I had fun talking to her so much is that I can relate to her despite the fact that we both come from very different backgrounds.

Photo: Bernice Beltran

8

No way is Beny like the bookish, quiet, nerdy Panamanian bird guides we were used to. His giant smile overtook his face and his laugh could be heard for miles. He was the funniest, most jovial bird guide we ever had, which is why we wanted to have him guide us to the birds again when we took our second trip to Panama. But alas, he was booked with another group. And then, while we were birding in the remote area of La Fortuna, who was that on the side of the road looking through binoculars? Why, it was Beny! Birds of a feather…

Photo: Lisa Boice

9

Smiling and prancing, the little one approached me, seemingly just to say hello. We talked about her favorite things. I asked her, “Do you live here in San Cristóbal de las Casas or nearby?” She just said, “Mami hace casa” (mommy makes the home). Ten minutes in, she hadn’t even attempted a sale so I asked her what she had in the basket. She proudly showed off her bracelets, and my heart quickly turned to goo. I ended up buying all 15 of them.

I then saw her go lie down with her mom. They were homeless. I wear the bracelets every day to remind me who I’m fighting for, and this photo serves the same purpose.

Photo: Caetano Laprebendere

Intermission

1

9 things you’ll miss after leaving Charleston, SC

by Caroline Davidson

4

Portraits from the streets of Havana, Cuba

by Chris Burkard

2

12 beautiful portraits of Black identity

by Amirah Mercer

10

We met each other in Spain, on the Camino de Santiago de Compostela, in April 2009. Today, we have a two-year-old baby boy named Tiago.

Photo: Thaís Chalencon

11

I love experiencing deep bonds with people after just meeting for the first time – it’s like you know that you have known them for countless lifetimes.

I met Craig while I was staying at a surf hotel a few months ago in Playa Guiones Nosara, Costa Rica. The first thing I noticed was his shining, bright eyes – they inspired me right away. Over that week I learned a lot about his adventurous travels back in the days when there were hardly any tourists, let alone surfers. He has spent life traveling, teaching yoga, and surfing – a beautiful being to meet.

Photo: Nat Kuleba

12

This Vietnamese lady spotted me on the busy streets of Hoi An and ushered me towards her fruit and vegetable stall. She sat me down on a little plastic stool, pulled off her traditional straw hat, and plonked it roughly onto my head. Clapping her hands in excitement she exclaimed in broken English, "Photo! Photo for pretty lady!" I had no choice but to hand over my camera to my dad who snapped the photo.

I went to stand up but she put her small arm around me and said "With me now!" I laughed at her eagerness and smiled for a photo once more. Before I could try to stand up again, she swiftly removed the hat from my head, put out her hand, and said "Okay, 10,000 Dong." I shook my head in disbelief and handed over the money. That sneaky lady!

Photo: Jess Buchan

13

Her name was Van, but we called her Vinny. On first impressions she was quiet, softly spoken, and shy about speaking English. Still, she was very accommodating to us weary travelers staying in her modest concrete home outside Ninh Binh in Northern Vietnam. The first night, Vinny and her mother greeted us with a home-cooked meal bursting with fresh produce from their garden. The next day, we took a day trip to experience a “charming” pagoda.

My impressions of her drastically changed when Vinny’s fiery yet polite stubborn goddess exposed itself. She could not be swindled into buying admission tickets from an insistent and pestering street hawker, and vocally stood up for me as a foreign traveler against a small mob of angry pagoda “guides” trying to get me to pay even more money for the visit.

Our time together ended suddenly as Vinny had to rush back home to catch a bus; she jumped onto the back of a motorbike and the driver zipped through the crowded streets, disappearing immediately. It was quite a privilege to spend two full days with the smiley and bright Vinny.

Photo: Bethany Coan

14

This is Jennifer Gall. I had actually met her friend first – a free spirit named Imogen who I met in Rome.

Imogen introduced me to Jennifer at the Trevi Fountain, and we all made lots of wishes together. Three years later, Jennifer and I met to celebrate our birthdays in Valencia after a long day at the tomato fest in Buñol. The night before the tomato fight, we shared a tent…and our life story – family, relationships, where we wanted to be three years from now.

Photo: Zoe Hatton

15

When I lived in China, early mornings meant "Get up and go exercise." Many people gathered at the parks or other open spaces to do Tai Chi Chuan, dance, run, or just walk. One of the walkers would be out there every morning to say hello to my Tai Chi partner and I. We never knew his name. We called him "Chairman Mao's Soldier.” He had on his CCCP jacket and pants from an earlier era. Plus he wore, with a great deal of pride, a badge bearing Chairman Mao's face. Always smiling, he was an everyday fixture.

We left for the summer and when my friend and I returned, we saw Chairman Mao's Soldier once. He looked tired and haggard. He told us he was 86 and not feeling so good. We never saw him again. I cried like I had lost a family member.

Photo: Carole Milstead

Matador Network's Blog

- Matador Network's profile

- 6 followers