Matador Network's Blog, page 2206

September 23, 2014

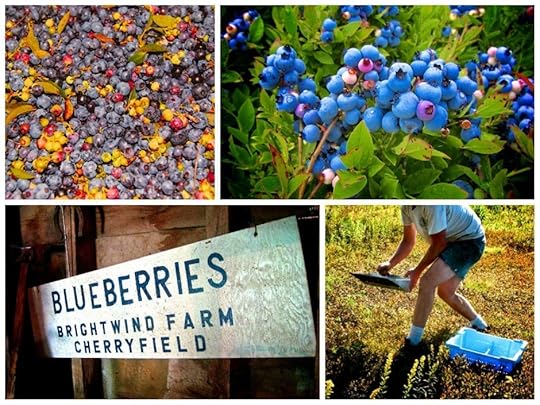

The story behind the Maine blueberry

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

When I was 13, my mom signed me up for a blueberry raking crew. She wanted my first real job — besides babysitting the neighborhood kids for $3 an hour — to be one of hard work. So she signed me up for the same manual labor she’d signed herself up for back in the early 1970s when she was about my age.

“When you close your eyes at night, all you’ll see is blueberries,” she told me.

She was right. Every morning before sunup in August, she drove me to downtown Winterport, where I’d wait in front of the gas station to be picked up by the crew. Sometimes they’d show up in an old school bus, painted white. Other times a pickup truck would pull up and whoever wanted to rake would climb in the back. I liked riding in the truck the best. Even in August, the morning air in Maine is prickling but with a promise that the sun might warm you by noon. I’d sit alone sometimes with my hood up around my ears, clutching my water bottle and granola bar for later. We’d get to the fields in Frankfort just as the sun was crowning over the hills of Waldo County.

And yes, she was right, all I could see before me were miles and miles of blueberries, whether my eyes were closed or not.

What my mother didn’t tell me about raking was that, as a kid who hadn’t yet been out of New England, the blueberry field would be my first piece of real evidence that other cultures existed. I’d often ride to the field with some local kids, but when I hopped out of the truck, I was a minority in my own home county. The fields were filled with people I’d never seen before, greeting each other in Spanish, sitting on overturned buckets and sipping on Styrofoam cups of coffee.

The Maine blueberry harvest used to be dominated by the Native American population, with most of the workers being either Passamaquoddy or Canadian Mi’kmaq. However, at the start of the 1990s, the labor force became overwhelmingly Hispanic. Today 83% of migrant laborers in America are Mexican, Mexican-American, Puerto Rican, Cuban, or from Central or South America.

I remember entire families — with children way younger than me — congregating in their assigned rows. Mothers swatted at their toddlers squatting down to eat the berries. The smells were completely foreign from the salty pine I was used to. The smoky scent of rocky soil and sweat hung in the air, mixed with the slight tang of pesticides sprayed on miles and miles of bright blueberries nestled in low bushes. For a 13-year-old Maine girl, raised in the same town her mother was raised in, the blueberry field was a mini-introduction to the many possible worlds beyond America.

Photo: Supercake

Harvesting blueberries is not the casual summer activity we saw so beautifully illustrated in Robert McCloskey’s children’s book Blueberries for Sal. It’s hard, manual labor. The fields are vast and barren, offering no shade cover as the sun beats down on your neck and shoulders. The hours are long. You get to the fields at first light and don’t leave until the operation shuts down — either because the field has been completely harvested or the sorting trucks can’t keep up with the amount of berries being raked.

If you make the mistake of popping a berry into your mouth, you won’t be able to stop yourself from taking handfuls. Not only will eating slow you down, it’ll cause you to spend most of your shift in the woods or in the outhouses — usually located on the back of a truck, which drives from field to field. The berries are heavily coated in powerful pesticides that don’t agree with any human digestive system. And the fields are not a good place to get sick.

You’re often working up- or downhill, trying to keep your footing while bending over and pushing or dragging your rake across the top of the bushes. Once you get a rake-full of berries, you winnow out the leaves, rocks, and sticks before dumping the berries into a box. Twenty-three pounds of berries will fill a box. You’ll stack your boxes in your row until you have time to carry them to the truck. When I was raking, you got paid $2.25 for every box you filled. On most Maine fields today, 12 years later, you’ll still get exactly that.

Even though I still sometimes saw them in my dreams, I didn’t step on a blueberry field again until I moved 60 miles east to Washington County earlier this year.

Washington County is three things to most Mainers. It’s the poorest county in our state, considered by many an exquisite place to pass through but too impoverished to live or raise a family. It’s the easternmost part of the United States, the first place to see the sunrise each morning. And it’s the blueberry capital of the world. My home fields in Waldo can’t compare to the powerhouse operation that goes on up here. The fields are no longer “the fields”; they’re “the barrens.” Named because they’re exactly that, barren. Millions of acres of wild blueberry bushes are intersected by hundreds of miles of dusty gravel roads. It’s easy to get lost here if you don’t know the landmarks — a rock that looks like a frog, a small monument, an abandoned cabin for sale. Without local knowledge, every direction looks exactly the same.

The barrens are so endless, landowners used to use planes and helicopters to spray pesticides aerially. Any Mainer who’s been here long enough can remember going inside their house to avoid the spray when they heard a low-flying engine rumble in the distance. In the 1970s, the pesticide mixture was believed to contain an identical nerve agent to one used in the Vietnam War.

The barrens span three towns — Milbridge, Cherryfield, and Deblois. The majority of the harvest used to be done by hand. Thousands of migrant workers would flood those three towns, bringing their families to work in the fields with them, just like I saw back home. Today, the majority of harvest labor is done by machine, so securing a spot on a raking crew is far more competitive; the number of laborers actually raking blueberries has dropped down to the hundreds. But the migrant population still has a strong presence in these small communities. Raking was a rite of passage for many local Maine families in the 1970s, but it isn’t so much anymore. So the harvest is still heavily dependent on these traveling laborers, coming from all over the continent to work it.

There’s no way around it — Maine is one of the least diverse states in the country. Ninety-six percent of its population is white. So it’s not difficult to notice the influx of hundreds and hundreds of Spanish-speakers arriving here for the harvest each year.

Photos clockwise from bottom left: Michael Rosenstein, Renee Johnson, Caleb Slemmons, Chewonki Semester School

Enrique is a 20-year-old from Georgia in a bright purple sweatshirt, a baseball hat, and a tattoo on his knuckles that reads “Sick Life” — he’s not a typical character you’d meet in rural Maine, and he knows it. He laughs and tells me that if we were in his hometown in Georgia, he’d never be “caught talking to a white girl.” But at the labor camp in Deblois he invites me to sit down with him and his friend Luis. They’re happily eating breakfast at a picnic table in the camp’s communal area — some large tents strung up over two Mexican food trucks.

Enrique came to the barrens with his father, who’s originally from Guanajuato, Mexico. Although this is Enrique’s first time in Maine, he’s heard about it from his dad, who’s come here for countless seasons, making his livelihood as a field worker traveling around the States.

“I love it here,” Enrique says. “It’s more natural, you know? Not like the city.”

When I ask Enrique if the raking is hard work, he says, “No, it’s mental. You have to keep thinking ‘I’m a machine. I’m a machine.’ If you don’t, your mind gets depressed and you don’t make that money.”

He says that sometimes his father sees him wearing down and taking a break. “My dad will come over and tell me to ‘Beat that demon! Beat that demon!’” Enrique and Luis laugh and briefly compare stories in Spanish. They’re each making their way through three breakfast sandwiches.

Enrique and his father came to Maine from New Jersey, where the blueberries grow on trees. “You have a basket on your waist and you just pick, pick, pick.” He says you don’t make as much money in the high-bush harvest because you have to fill a larger basket and you’re using your fingers to pick, instead of a rake. When August is over, they’ll head to Pennsylvania to pick apples. When that harvest is done, they’ll come back to Maine to make wreaths for the winter.

Enrique says that although “it’s good money” — his best day this season was 150 boxes, not typical but about $340 dollars — he doesn’t want to work in the fields forever. “I’m looking for a school where I can learn sound engineering,” he said. “Then I can come back to places like these and offer them opportunities. You meet all different types of people here. I would like to hear and share their stories.”

Because of the conversion to mechanical harvesting, many migrants have gone instead to work in the local sea cucumber processing plant, where the meat of the unique, slick sea creature — usually just called pepinos because there isn’t even a name for them in Spanish — is scooped away from its skin for $1.75 per pound. It’s then shipped off to China to be used in specialty cuisine. And like Enrique and his father, many migrants will come back and stay in Maine through the winter to make wreaths, weaving sprigs of pine onto wire to be shipped all over the world in time for Christmas.

Because of these seasonal work resources for the traveling families, the multiculturalism in this sparsely populated Maine county is extremely prominent. Many families have become year-round residents of Maine and have lived here since the ’90s, opening their own businesses — an auto body shop, a painting business, and a locally infamous Mexican restaurant called Vazquez.

“[Migrant families] come from close-knit communities. They look for that in the States,” says Ian Yaffe, executive director of Mano en Mano, a nonprofit organization devoted to advocating for these diverse populations. “They have traveled thousands of miles in some cases to be here…they come here for community, they come here for schools, quietness, to be part of a close community.”

Rural Maine culture is in many ways similar to home for these families. People live closely here. Families, like my own, often date back multiple generations in the same town. Community gatherings such as potluck suppers, school fundraisers, and concerts are always heavily attended. People stop and talk in the grocery store, and every passing car waves to you when you drive down the road.

There’s even a soccer tournament out at the labor camp every year at the end of the season. The first match is always Mexicans vs. Americans. Whoever wins goes on to be defeated by the Hondurans. Many community members — who’d never come up to the barrens otherwise — attend the event, setting up lawn chairs in the back of pickup trucks, drinking cans of koozie-concealed Bud Lite, and swarming the food trucks at halftime for authentic Mexican empanadas.

The local grocery stores have made a point to always have a Spanish-speaker on staff, and when Mano en Mano offered free language classes this past winter in both English and Spanish, more people came to learn Spanish.

Many of the migrant families who’ve chosen to settle here are from the same areas of origin. There are 300 to 400 people with roots in Michoacán, Mexico, now living in Milbridge, Maine, a town with a population of just 1,353. Silvia Paine is one of these community members. She came by herself to Milbridge in 2005 from Morelia. Silvia usually works at the sea cucumber plant and makes wreaths in the winter. Her two children came later to work at the blueberry factory.

Silvia’s first impression of Maine was that it was a “beautiful place.” But integrating into the community was difficult. “I didn’t know English. It was hard to communicate. I had to call friends sometimes to help me,” Silvia remembers. “But in time I have been learning a little more.”

Silvia took advantage of Mano en Mano’s advocacy programs to help gain confidence in the community. Mano en Mano helped her find a health provider and offered to help her with translation. Nearly 10 years later, Silvia says that Maine has become a new home for her. “Yes, I feel part of them now. I love this place. I love the people. Everyone is polite and kind.”

Ian says that even with the well-known Maine mentality of resisting outsiders and change, Washington County has been very accepting of its newfound diversity. The local grocery stores have made a point to always have a Spanish-speaker on staff, and when Mano en Mano offered free language classes this past winter in both English and Spanish, more people came to learn Spanish. There are exceptions, of course — “individual attitudes who are not accepting of newcomers in general.” But the fact that these are the exceptions and not the norm is significant.

Jenn Brown, Mano en Mano’s director of student and family services, believes the migrant community adds “excitement, vibrance, and complexity” to the Washington County area. She notes that if people aren’t accepting, it’s most likely because they’ve never interacted with these families.

“Many people here have never even been to the barrens,” she says. “Sometimes that’s just the way we do our lives. We don’t always pay attention.”

17 Thai dishes you have to try

Thai restaurants have gained popularity around the world, primarily due to the cuisine’s strong flavors and diverse ingredients. While simplicity is emphasized in many international cuisines, Thai food is not one of them — dishes often include a laundry list’s worth of ingredients, and they harmonize to create impressive (and delicious) results.

Check out 17 of our favorite Thai dishes and drinks before hopping a flight to Bangkok or heading to your local Thai spot to give them a try.

Eat

Nuea daet diao kaphrao thot

Photo: Takeaway

A dish that’s frequently consumed with alcoholic beverages, nuea daet diao kaphrao thot is sun-dried beef that’s subsequently deep-fried. It’s mixed with crispy fried basil, and served alongside a spicy dipping sauce.

Khao man kai

Photo: Takeaway

The Thai version of Hainanese chicken rice, khao man kai is not often seen on Thai menus in the West. The dish is created by topping garlic-steamed rice with sliced chicken, chicken broth, and served alongside a spicy sauce.

Khao tom kui

Photo: Takeaway

Khao tom kui is plain rice congee. Often accompanied by various side dishes, the affordable dish is typically eaten for breakfast. Other variations of the dish include meats and green onion as well.

Kai yang

Photo: Takeaway

Kai yang originated in Laos and northeastern Thailand (namely Isan), but can be found all over Thailand today. The dish, marinated (and heavily seasoned) chicken grilled over charcoal, is typically served with som tum and sticky rice.

Laap pet

Photo: Garrett Ziegler

Found in many Thai restaurants, laap pet is another northeastern Thai dish. It’s minced duck (served either cooked or raw), typically seasoned with fish sauce, lime juice, and other aromatics before being mixed with chili and mint. Sticky rice is the usual accompaniment.

Yam pla duk fu

Photo: Takeaway

Yam pla duk fu is an Isan dish consisting of crispy fish (pla duk) and spicy mango salad. The salad is typically served in a bowl separate from the fish, allowing the fish to remain crispy.

Sai krok Isan

Photo: Ron Dollete

One of northern Thailand’s most famous foods, sai krok Isan is a sausage made from salted ground pork, chopped garlic, and glutinous rice. The sausages are left to ferment for several days before grilling, giving them a distinct flavor.

Som tam

Photo: Karen Blumberg

One of Thailand’s more popular salads, som tam is made from unripe papaya mixed with lime, chili, salt, fish sauce, and sugar. Traditionally, the ingredients are pounded together with a mortar and pestle.

Kor moo yang

Photo: Jeffrey Chiang

Not the most complex dish in terms of ingredients, kor moo yang is seasoned and marinated charcoal-grilled pork neck. Another Isan dish, it’s typically served with a chili-based dipping sauce.

Khao nia mamuang

Photo: Dorami Chan

A dish served at both restaurants and street stalls while mangos are in season, khao nia mamuang is made from sweet sticky rice and mangos. The glutinous rice used in this dish is typically sweetened by adding coconut milk.

Kaeng khiao wan

Photo: Takeaway

A dish seen both in the West as well as Thailand, kaeng khiao wan is a central Thai dish meaning “sweet green curry.” The dish’s base comes from coconut milk and green chilies, from which it derives its name.

Roti kluai khai

Photo: Su Lin

Seen in street stalls, roti kluai khai is a type of “pancake” filled with banana and egg (which are fried inside the roti). The food is often sweetened with condensed milk and sugar, or topped with chocolate syrup.

Tod man pla

Photo: Takeaway

Tod man pla is a dish consisting of deep-fried minced fish mixed with red curry paste, long-beans, and kaffir lime leaves. It’s typically served with a sweet dipping sauce.

Khanom tom

Photo: Dorami Chan

Khanom tom is created by boiling glutinous rice flour, sugar, coconut cream, and other ingredients. After being boiled, the balls are rolled in grated coconut. The dish is served as a street food.

Drink

Krating Daeng

Photo: Danny Choo

The inspiration for Red Bull, Krating Daeng is a sweet (much sweeter than its world-famous counterpart), non-carbonated energy drink found in Southeast Asia. The beverage’s ingredients include water, cane sugar, caffeine, taurine, inositol, and B-vitamins.

Cha yen

Photo: I Believe I Can Fry

Known as Thai iced tea in English, cha yen is a strong Ceylon tea. Mixed with a multitude of ingredients, cha yen is sweetened, chilled, poured over ice, and served with milk. It’s often seen consumed from a plastic bag.

Beer Chang

Photo: Mark Fischer

Thailand’s number-one selling beer, Chang’s alcohol by volume is over 6% when brewed for local consumption. When exported, that figure drops to 5%. It’s not uncommon to see the beer being consumed from a 640ml bottle.

September 22, 2014

What it's like to visit Somaliland

Photo: Teresa Krug

There’s a competitive rule in travel culture that long-term travelers come to realize: All countries are categorized by their coolness. Usually, the more dodgy a place is, the more kudos and bragging rights you get for visiting it.

Europe, for instance, is for beginners. Australia, the US (except Alaska), and New Zealand are Level 2 cool. Level 3 is Southeast Asia — a place for mildly hardcore travelers and avid grasshopper eaters. Africa, meanwhile, stands somewhere on the the same level as Papua New Guinea, remote islands in Indonesia, and unexplored corners of the Pacific.

Somaliland is an Expert Level destination, along with such little-visited countries as Chad, Mauritania, Congo, etc. If you go to Somaliland, you’re almost certainly going to become an obnoxious, know-it-all modern day Ibn Battuta. If you hitchhike in Somaliland, like I did, you effectively purchase the right to never shut up about how amazingly bizarre the experience was.

The first thing you should know about Somaliland is that it’s an incredibly boring country bordering Djibouti, Ethiopia, and Puntland, located just across the gulf from Yemen. You don’t have to dodge bullets and missiles; you don’t have to shoot kidnappers in the face; and you can’t explore all that much because the police simply won’t let you.

Since its declaration of independence in 1991, Somaliland has not succeeded in gaining any official recognition from the world, nor has it managed to develop a tourism sector — for obvious reasons. The atmosphere in the country reminds one a little bit of Kosovo, a country in progress, a country seeking recognition. A country that scares everyone off because of instant associations with war, destruction, and babies chopped into pieces.

Although a heavy military and police presence in the country provides a relatively safe atmosphere for travelers, not many holiday makers wake up with the idea of surfing the Somali beaches. My visa, obtained 10 minutes after application at the Liaison Centre in Addis Ababa, stated I was visitor number 635 this year.

Despite the fact that many people from the Somali diaspora abroad keep coming back to invest in their homeland, most of the locals remain unemployed, bored, and wondering: “Why the hell would somebody return here if they could have a brilliant life overseas, away from camels, sand, and banana peels?”

Traveling back to Hargeisa, I hitchhiked in the wreck of a car. “It was rock, rock on the glass!” the driver yelled happily, indicating the gigantic gash in his windshield.

I asked Mo, the owner of “Starbucks” in the coastal town of Berbera, why had he left the States after almost 30 years and returned to Somaliland. “The reason I came back is mainly adventure. Here, in Berbera, time isn’t going too fast, I can do a lot of things during the day, as well as sleep and relax, do whatever I want. In the US, there is no time, everything happens too fast, everyone is stressed out,” he replied. “Having a US passport is great for traveling, and I will visit the States for holidays, but I can only imagine myself living here, in Somaliland.”

Another family I spoke with, forced to come back home, was not content with their uncertain future as young professionals in a country with little economic opportunity. This especially concerns women, who have to get by in a traditional Muslim society, where female genital mutilation and early arranged marriages are still practiced.

Exactly how boring Somaliland is really depends on your definition of fun. If you’re seeking fine sights, hundreds of Chinese bristling with cameras, exotic dancers, and cosmopolitan night clubs, brace yourself for disappointment. If, however, checking out 6,000-year old cave paintings, armed escorts, and smelly fishing ports is your favorite way to spend a holiday, then this crazy land is right up your insane alley.

The rock paintings at Laas Geel are perhaps the biggest attraction, although not really accessible by normal transport (as of October 2013). The police need to provide you with an armed soldier and a driver (unless you have your own car) that accompany you to the caves. Bad thing: You end up paying a lot. Great thing: You get to hang out with Somali soldiers and take a photo like this (hey might even lend you the AK-47):

Photo by the author.

The Laas Geel caves were occupied by local pastoral tribes ca. 9,000 to 3,000 BCE. Bored shepherds used to hang out here and draw pictures on the walls. Most of them depict cattle, mainly cows, along with several human figures performing hunting rituals. I prefer to imagine them as bored teenagers expressing themselves through graffiti.

Not all of Somaliland is endless desert, and the colours of this country surprised me while I hopped from Hargeisa to Berbera, from Berbera to Sheekh, and back to Hargeisa once more. Berbera is an excruciatingly hot coastal town with decaying coral buildings, where you can eat nothing but fish in fish sauce with fishy fish on top. Sheekh, on the other hand, is connected to Berbera by an incredible desert highway that gradually transitions into green valleys filled with old colonial houses. Foreign travelers are a rare sight here, and if observed from a distance should be approached with caution and offered sweet milk tea.

Catching a ride with a truck is a normal thing in Somaliland for both men and women, although a small payment is always expected. I managed to hitchhike in a truck that was transporting packs of money to the bank in Berbera.

Traveling back to Hargeisa, I hitchhiked in the wreck of a car. The driver was delighted to have me on the passenger seat, though I felt like sitting in the back instead. “It was rock, rock on the glass!” he yelled happily, indicating the gigantic gash in his windshield.

I was not lucky enough to hitchhike in the fastest truck in the country — the one transporting khat from Ethiopia all around Somaliland. Running at 100mph and almost flying on the sand ramps, this vehicle makes sure everyone in Hargeisa and beyond gets their day’s share of magic grass.

The country is a bit of a different planet, isolated in its territorial limbo and muddling along with the help of international NGOs. The streets of Hargeisa smell of guavas, and are filled with goats and camels, along with modern coffee shops and restaurants. During the day, you hide in the shade, drinking fruit juice, munching on sandwiches, and answering the same question from every new acquaintance:

“So, how do you like it here?”

This post originally appeared at Do you want to see my spaceship? and is republished here with permission.

9 signs you're a hostel noob

Photo: AsaPeka

1. You think everyone in your dorm is the coolest person you’ve ever met.

You’re Australian and you like surfing? Awesome! You’re a Minnesota college volleyball player and it’s your first time out of the country? Wow!

Everyone you meet at the hostel is so exciting and new, you indulge in even the most mundane of travel tales, from the group of study abroaders who refuse to eat anything Czech and have Dominos delivered to the hostel, to the dude who’s kind of creepy in his stained Jimmy Buffet shirt. But, hey, you have to give him credit for traveling to Mexico City on his own at 45!

2. The promise of free breakfast excites you.

Anything free is your favorite flavor, and the fact that this hostel is providing you with one less meal to buy was incentive enough to book. It doesn’t matter that the selection consists of some cereals, slices of white bread, a few tomatoes, and watered-down coffee — free is free, so you’re stuffing your face with stale muesli and washing it down with watery juice from concentrate. That ought to hold you over till lunch.

3. You forgot shower shoes.

And earplugs. And a sleep mask. And your own silverware. And enough underwear.

4. You pseudo-trust the luggage storage situation.

You’re always wondering if someone is going to accidentally “claim” your luggage as theirs, but dealing with an overstuffed backpack at a tiny yet sophisticated cafe in Paris or a clunky rolling suitcase while trying to get to the Forbidden City in Beijing totally sucks.

So you say “fuck it,” and hope your belongings aren’t rifled through after the baked-out-of-his-mind front-desk clerk leaves the storage room blatantly unlocked.

5. You fall in love with the reception workers.

Hot. Austrian. Twentysomethings. They have the best job in the world, they have free rent, and they’ve even offered to take you out for a drink at Centimetre on Stiftgasse. They speak five languages and laugh sweetly when you mispronounce Fleischpalatschinke. Even the guy who plunges poo from the toilets is sexy because he speaks five languages and complimented your henna tattoo.

6. You turn into a musician.

Paolo is playing his weathered acoustic guitar, Jorge is beating lightly on his bongos, and you’re pretending to know the words to whatever Argentinian love song they’re belting out in the common room.

7. You’re all about sharing.

You take Shiloh up on his offer to share his vegan lentil stew, when he notices you’re sitting in the hostel kitchen by yourself, hoping you don’t have to dumpster dive for your dinner. Or you bought a huge tub of peanut butter, but don’t get too mad when you notice half of it gone the next day, because you couldn’t bring it with you on the plane from London to Amsterdam anyway.

When your towel goes missing, you’re a little pissed, but feel better when a smokin’ hot Colombian hands it back to you with a smile.

8. You don’t sleep.

You catch a total of two hours shuteye, either from partying too hard with that one Irish guy, or because the soccer team from Bel Mar, Maryland is snoring too loud, or because you’re still hella jet-lagged.

Why Americans have an NYC complex

Photo: Celso Flores

A few years ago, the aquarium in Newport, Kentucky decided to bring back their popular shark petting zoo exhibit. When the exhibit had been there several years before, they’d flooded the local media market with ads showing people how to pet sharks: with two fingers, always front to back. The shark petting zoo’s triumphant return was advertised with this incredibly ill-advised billboard:

(via)

At the time, I was still living in my hometown across the river from Newport, in Cincinnati, Ohio. I saw this billboard once before they hastily pulled it down, and because it’s a comedy goldmine, I tell the story behind it every chance I get.

One day, I finished telling the story to a friend, and after giving me a polite, placid-faced smile, she said, “I guess in really cut-off, provincial places, it’s easy to think the whole world remembers your ad campaign.”

The “Greatest City in the World” vs. the “Flyover States”

Now, before I go any further, let’s get one thing straight: The Greater Cincinnati metropolitan area has over two million people in it. We’re not some backwoods, podunk, hick town that calls people “city slickers” because they don’t tan their own leather. And we’re not cut off from anything. We have an airport. We have internet. We have roads. We’ve even got our own television sets.

There is, in fact, only one type of person who could think that Cincinnati is “cut off” and “provincial”: a New Yorker.

This isn’t an isolated phenomenon. It’s a regular occurrence. I had another New York friend tell me “it doesn’t count as a real city if there’s less than a million people in the actual downtown.” Which would mean there’s only nine cities in the United States. And those nine don’t include Boston, San Francisco, or Washington, DC. I’ve had other New Yorkers say, “I’m sorry,” when I say I’m from Ohio. And they have a tendency to call NYC “the Greatest City on Earth,” which sounds like a statement about New York to them, but to me it sounds like them saying “We’re better than you.”

Clearly, I have a New York complex. Clearly, I’ve been holding these petty grudges for years. Clearly, this isn’t about New York — it’s about me. And clearly, I’m not alone.

The fine, grand tradition of hating New York

The refrain of Midwesterners everywhere — which is to say the Midwesterners that haven’t already abandoned their hometowns and moved to New York — is, “Oh, New York is nice to visit, but I’d never want to live there.” Then they tell a story about a bum spitting on their 10-year-old child, or about a cab driver who called their elderly grandmother a “cunt” for not getting through the crosswalk quickly enough.

The stories are almost always exaggerated (for example, that bum only tried to spit on me when I was 10 and visiting Manhattan with my family), and some of them are patently untrue. But they are ubiquitous. Middle-American hate for New York is probably best expressed in the quintessentially middle-American show, The Simpsons, in the episode “The City of New York vs. Homer Simpson.” As the Simpson family pulls into the Port Authority Bus Terminal on a ratty bus, Marge looks out the window at the city and says, “Wow, I feel like such a nobody!” The scene then pans down to a billboard that says, “Welcome to Manhattan: Home of the World Weary Poseur.”

David Simon, the famously cynical Baltimore native and creator of The Wire, was asked about New York and went on a long rant about the city, calling it “vain,” “indifferent to other realities,” “self-absorbed,” a “pile of money.” He then went on a tangent about how hard it is to live in New York’s long cultural shadow.

Insecurity and jealousy

“New York City to a Midwesterner,” my friend Jesse Steele says, “is what I imagine it must be like to be just a regular dude and have your older sibling be elected president. No matter what you do, even if you’re smarter, stronger, better, cooler, whatever, your older brother will still be the president, and you’ll still be not the president. Like the president, New York doesn’t have to do anything to be better than you.”

Most of the New York haters would have to admit there’s some pretty amazing stuff in New York. Broadway is awesome. The food and art scenes are bananas. And there are famous people everywhere. So yeah. A big element of New York hate is jealousy, and it can come out in ugly ways.

When Sarah Palin called the heartland the “Real America” during the 2008 campaign, she was playing on that nagging insecurity felt so strongly in not-New-York areas. She confirmed for them what they’d always hoped: that they were better than New Yorkers! Pop culture had been lying to them all along!

Anti-New York sentiment can also be coded anti-semitism or racism. As a city that’s perceived as heavily Jewish, heavily black, largely progressive, and incredibly diverse, The City is prone to the projections of latent bigots and hardcore conservatives. Thus, New York’s pros are turned into cons: Instead of a shining Metropolis, a beacon on the hill, it’s a modern-day Sodom and Gomorrah.

Getting over it

I’ve resented New York for years now. But resentment belongs solely to the resenter and not to the resented. New York is indifferent to my insecurities. It isn’t interested in the chip on my shoulder. It’s busy being motherfucking New York.

I’ve noticed people from other great cities — Austin, San Francisco, Seattle, Denver — tend not to care that much about New York. Sure, it might not be their place, but they don’t stew in their hatred. They’re too busy building something awesome of their own. Which is perhaps what my New York-hating brethren and I should be doing as well.

People's Climate March drone footage

Follow Matador on Vimeo

Follow Matador on YouTube

I CURSED MY CHOICE to drive through midtown NYC on Sunday, after being stuck in almost 45 minutes of traffic from the Lincoln Tunnel to Park Avenue. Later I found out that the linear traffic was due to the People’s Climate March, a gathering of allies in more than 162 countries (with over 310,000 New Yorkers participating alone, the largest rally of the day) to support stronger environmental initiatives. The march was a preview for events happing on September 23rd, when leaders from around the world will come together to discuss the fight against climate change.

This drone footage truly shows how massive (and motivated) the crowds were on September 21, 2014, in an effort to spur “Action, Not Words, and stand up to climate change in effective ways.

3 adventurers who died exploring

Image via

We live in a culture that lionizes adventurers and risk-takers. And for good reason — without these people, we wouldn’t have explored the world, reached the highest peaks of the Himalayas, tested the limits of human endurance, and made the most of our epic discoveries. The risk-taking ethos is also fundamental in the philosophy of travelers. No matter how safe you choose to travel, wandering out your door is way more risky than staying put.

We tend to gloss over the one major downside of their risk-taking: Sometimes, it doesn’t pay off. Sometimes, it ends in death. These adventurers deserve our respect for their feats, but their deaths deserve our respect, too. We can learn just as much from their tragedies as we can from their victories. Here are some adventurers who paid the ultimate price adventuring.

Dave Shaw

Dave Shaw was a deep-sea diver and cave diver who set several records in South Africa’s notorious Bushman’s Hole. The Hole looks from the top like a puddle, but as you step into it, you quickly realize it’s actually a sinkhole. It’s one of the deepest sinkholes in the world (nearly 1,000ft deep), and also a particularly deadly one. In 1994, a diver named Deon Dreyer died during a dive, and his body wasn’t recovered. Dave Shaw found Dreyer’s body on a dive, and decided to set up an extremely risky body recovery attempt. SnapJudgment, a public-radio program, did this incredible report on the dive:

Shaw didn’t survive the dive, but he managed to strap Dreyer’s body to his. So when Shaw’s body floated to the top, he brought Dreyer with him, thus fulfilling his promise to return Dreyer’s body to his parents.

Chris “Alexander Supertramp” McCandless

You’ve probably heard of Chris McCandless. He’s the subject of Jon Krakauer’s great book Into the Wild. Fed up with a life that expected him to conform to societal standards of “success,” and inspired by heroes like Thoreau and Tolstoy, McCandless donated all of his money to Oxfam and left his old life behind without a word to his parents.

He spent two years wandering around the country on a nomadic quest of sorts, until he finally reached Alaska. He hiked into the wilderness with inadequate supplies and a naive belief that he could “rough it” and come out alive. He did not.

Much controversy has surrounded McCandless since his death. Many see his naivete and hubris and believe that, at best, McCandless serves as a cautionary tale for what extreme idealism can result in when it isn’t coupled with experience. Others see him as an inspiration, a rare person who managed to drop everything he owned and abandon the rat race entirely — a boy who became his own man on his own terms.

It’s hard to argue with either camp. “The Edge…,” Hunter S. Thompson once said, “there is no honest way to explain it because the only people who really know where it is are the ones who have gone over.” McCandless went over the edge, and the rest of us are left wondering what he learned and whether it was worth it.

Hendri Coetzee

Hendri Coetzee was an adventurer and humanitarian who kayaked the Nile River from source to sea — a notoriously difficult feat — in order to raise awareness of the humanitarian situation in the countries along the Nile. In 2010, he organized a similar trip through the Congo, and was in a little-known part of the river with two American kayakers when a crocodile burst out of the water, flipped him over, and dragged him under. His body was never found.

Two weeks before Hendri died, he wrote the following on his blog:

“It is hard to know the difference between irrational fear and instinct, but fortunate is he who can. Often there is no clear right or wrong option, only the safest one. And if safe was all I wanted, I would have stayed home in Jinja. Too often when trying something no one has ever done, there are only 3 likely outcomes: Success, quitting, or serious injury and beyond. The difference in the three are often forces outside of your control. But this is the nature of the beast: Risk.”

5 Greek islands you don't know

I first traveled to Greece as a child and remember being immediately caught up in the country, a sentiment that still strikes me today no matter how many times I visit, or how many years I’ve lived there. “The light of Greece,” as Henry Miller wrote, “opened my eyes, penetrated my pores, expanded my whole being.”

I’m often asked which Greek islands I’d recommend others visit — an impossible feat, when each of the country’s 6,000 islands and islets vary greatly in history, scenery, and activities. From parasailing to forest trekking to sunbathing on secluded beaches, each is special in its own way.

Here are five islands most travelers have never even heard of, and why you should see them now.

1. Nisyros

Photo: Visit Greece

Photo: Visit Greece

Photo: Matt Boyd

Photo” Matt Boyd

Floating between the islands of Kos and Tilos, Nisyros is part of the Dodecanese group of islands, and is known for being the youngest volcanic island in Greece. You can safely walk in the craters — the last violent eruption occurred in 1888. Like many islands in the southeastern Aegean, Nisyros was at its most prosperous in the 5th and 4th centuries BC. One notable element of modern Nisyros is that its houses, temples, and castles have virtually all been built with some component of the volcano — black lava, pumice, red and white rust, etc. Today, the island is a green enclave primarily known for its nature tourism and hot springs.

2. Paxos

Photo: Sean Perry

Photo: Rick Mn

Photo: Smoob

Photo: Carolina Georgatou

Photo: Sean Perry

Located south of Corfu on the northern side of the Ionian Sea, Paxos is said to have almost been the southernmost tip of Corfu. According to lore, Poseidon, god of the sea, separated the two by breaking off Paxos with his trident when he needed a place to live with his love Amphitrite. Though Poseidon chose Corfu, the tiny oasis of Paxos — the smallest of the Ionian islands — is the real winner. I enjoy its fjord-shaped beaches, underwater caves, small bays, and green hills. The nearby islet of Antipaxos also has Caribbean-esque waters and some of the best beaches in Greece.

3. Milos

Photo: Massimo Palmieri

Photo: Klearchos Kapoutsis

Photo: Jeremy Jones

Milos, another volcanic island, is the southernmost island in the Cyclades. It’s known for its horseshoe shape and coastline, which comprises more than 75 beaches of different varieties. It has nearly 5,000 residents, and is also where the famous statue of Venus de Milo was found in 1820. While whitewashed houses on Greek islands are familiar sites, Milos has gone a different route, with small, colorful houses by the sea where fishermen shelter their boats in winter. Also of note are the catacombs of Tripiti, which were discovered in 1844 and appear to have been built toward the end of the 1st century, marking the era when Christians came to Milos.

4. Alonissos

Photo: Constantin Pilavios

Photo: Son of Groucho

Photo: Dinos

Photo: Visit Greece

The most remote island in the Northern Sporades, Alonissos is home to the National Marine Park of Northern Sporades, a refuge for rare seabirds, dolphins, and the Mediterranean monk seal. It’s 13 miles long, almost three miles wide, and has a population of roughly 2,500. Historically, the Cretans are credited with establishing colonies on Alonissos (then known as Ikos) during the Minoan domination of the Aegean Sea, circa 16th century BC. The Cretans also introduced winemaking to the island, and to this day local Alonissos wine remains excellent.

5. Ikaria

Photo: Raphael Kominis

Photo: Joakim Lind

Photo: Thanasis Theocharidis

Photo: Raphael Kominis

The 99-square-mile Ikaria was named after the myth of Icarus, who ignored his father’s advice and flew too close to the sun. His father collected his body when he fell and is said to have buried Icarus on the nearest island — Ikaria. The island is apparently also birthplace to Dionysus — god of wine and drunken revelry — and the home of water nymphs. Today, Ikaria is primarily visited for hiking and outdoor activities. Mostly mountainous, it’s covered by oak, pine, and cypress trees. During the summer, one of the most genuine Ikarian experiences is to partake in a feast, which happens — either for religious or social reasons — almost daily.

The best food and brews in Utah

The spread at Roosters Brewing Company in Ogden, another fine purveyor of Utah food and brews in addition to those below.

Black Sheep (Provo)

When most people think of the cuisine of the American Southwest, they immediately jump to Mexican. For some reason, the only food north of the border is south-of-the-border. Most people forget that Utah was and is inhabited by Navajo, Ute, Shoshone, and other native peoples, who shaped the culinary landscape of the area for thousands of years before the Europeans arrived with their Tex-Mex.

Luckily, Mark Daniel Mason isn’t most people. His Black Sheep Café in Provo is keeping those native cuisines alive by putting them at the forefront of the menu, integrating the corns, beans, and squash (the “three sisters”) that defined the diets of so many original Americans into the palates of diners trying the flavor combinations for the very first time.

Of course, America is still a nation of immigrants, whether they arrived by boat or ancient land bridge. It would be foolish to pretend those Spaniards (and their Tex-Mex) hadn’t earned a place in our collective gullets as well. Mason makes sure to include them in a natural fashion, whether by fusing the styles and techniques or offering a choice between the two. In that way, Black Sheep Café may just be the best place to go for a comprehensive take on Utah cuisine — past, present, and future.

Squatters Pub Brewery (Salt Lake City)

The cream rises to the top. It’s a good expression, and one equally applied to the best heads on craft beer. Dan Burick would know. The guy is a brewing whiz, having studied at the best brewery school in Munich. Now he’s the brewmaster at Squatters, guiding the tastes and trends of one of the largest and most critically lauded craft breweries in the state.

Head to the main Squatters brewpub in Salt Lake City to see exactly what Burick is up to. You can sample all the tried and true — and all the new — beers they put out, paired with some great upscale Southwest pub fare. Go classic with a plate of Squatters Legendary Buffalo Wings or Roadhouse Nachos, get creative with a Thai Yellow Curry or Jambalaya entree, or scratch all that and take a deep dive into the House Taco options.

Squatters is a good brewery to support; with a motto of “People, planet, profit,” they put social responsibility first, and since being founded in 1989, they’ve spent a huge portion on sustainability. It’s paid off; this year they’re celebrating their 25th anniversary.

Alamexo (Salt Lake City)

A few years ago, there was a humble restaurant known as Zy. By all accounts, it was…decent. You’d go there. You’d eat some good food. But the chef, Matthew Lake, wasn’t necessarily invested in the trends of the cuisine Zy served — instead, he’d won the Best New Chef award in Washington, DC for his work in Mexican, while also cooking at Rosa Mexicana, New York City’s first real upscale Mexican eatery.

More like this: Guide to the best apres ski food and brews in Utah

Earlier this year, Lake shuttered the doors to Zy, and in an impossible four days, reopened the restaurant as Alamexo, returning to his south-of-the-border roots. And if Zy never quite hit the mark, Alamexo is a sharpshooter. The dining room has been turned into an open space that takes advantage of the communal tradition of Mexican cooking — guacamole made tableside and served in a stone mortar, a focus on side dishes made for sharing. It’s a return to what made Lake passionate about cooking in the first place, and people are taking notice. Alamexo was named Best New Restaurant by Salt Lake Magazine this year, which surely looks like a fitting partner for the Best New Chef award already sitting on Lake’s mantle.

Hearth on 25th (Ogden)

Everything old is new again. Hearth on 25th has been around for over a decade under the name Jasoh, but in 2013 underwent a metamorphosis into the fire-tinged kitchen of its current incarnation. Like Alamexo — which was really following in Hearth’s footsteps, not the other way around — Hearth on 25th was originally a restaurant that got good reviews and had a following. And like Matthew Lake, executive chef Kyle Lore wasn’t happy simply getting good reviews.

In its current form, the restaurant focuses on seasonal cooking and live-fire dishes, having opened the dining room and shifted the focus to the giant central oven. Pizza is a popular item on the menu, but Lore, who has since moved on to other projects, wouldn’t have made the changes if he were happy doing the same dishes being served around the block. He prides himself on serving elk and Himalayan yak to people who find cows a bit outdated.

And like the other Utah farm-fresh establishments on this list, Hearth is devoted to supporting both Utahn farmers and the environment. All the produce in the restaurant is organic and grown hydroponically in-state. Cross Quarter Circle Ranch, where they source most of their meat, is 100% female owned and operated, making it a fairly new idea in terms of what people expect from a ranch. Such new ideas are deftly integrated into each dish, which only serves to reinvigorate every other aspect of the restaurant.

Wasatch Brewpub (Park City)

Wasatch taps. Photo: Justin Fincher

Remember Dan Burick? He’s the brewmaster of Squatters, and his brewpub in Salt Lake is one of the best places in the state to grab a cold one. But that’s not his only gig. Wasatch is another brewery he leads, in a partnership with Squatters dubbed the Utah Brewers Cooperative. But while he’s the brain behind the beer, there’s another name that needs mentioning — another guy who doesn’t abide by the rules, unless he makes them himself.

Greg Schirf owns the Wasatch Brewpub in Park City, and he’s the reason it’s been able to flourish. Hell, he’s the reason it exists in the first place, and has been going strong for 28 years. Schirf is a rebel in a land of rules, making waves from the moment he arrived and changing the landscape of foamy beverages in Utah. He lobbied for the legalization of brewpubs and Utahn brewing through such irreverent methods as reenacting the Boston Tea Party with beer (complete with 18th-century outfits), and it worked.

Though he’s already won the battle, that irreverence lives on. Try his Evolution Ale (“The fossil record proves one thing: that beer alone is responsible for the evolutionary leap from ape to man”) or Polygamy Porter (“Why have just one?”).

Logan’s Heroes (Logan)

A restaurant doesn’t need a pedigree to be great. It doesn’t need a well-known name manning the grill, it doesn’t need a hundred-year history, and it doesn’t need awards. All a restaurant needs to be great is great food and a little hometown support.

Logan’s Heroes certainly doesn’t have a pedigree. The sandwich shack takes up about the same space as the cars that park next to it. There’s rarely more than one person working at any given time, and they definitely weren’t trained at Le Cordon Bleu. But despite all of that, Logan’s Heroes has become one of the most beloved places in the state — topping Best Restaurant lists that include places that cost ten times as much and have a real dining room.

The sandwiches are great, of course. But the real magic of Logan’s Heroes is the connection it shares with its customers. The staff who know people by name. Those who sing Logan’s accolades are old college graduates craving that college cheapness, parents trying to satisfy their kids, businessmen on their lunch break. A $6 sandwich might be the only food everybody on the planet will enjoy. Or at least, everybody in Logan. The shop has its name for a reason.

Pago (Salt Lake City)

Scott Evans, the owner of Pago, used to be the general manager of the primary Squatters Brewpub. He’s firmly entrenched in the state’s foodie scene, taking experience and connections with him as he moved to opening a more traditional restaurant. But Evans still completely buys into Squatters’ social consciousness, so it makes sense that his solo endeavor would base itself around a farm-to-table ethos, supporting Utahns first and foremost.

Plan your trip: 5 Utah towns on the edge of spectacular nature

The other half of the equation is Phelix Gardner, the executive chef. He wasn’t there from the beginning, and though Pago opened to strong accolades, it was Gardner’s introduction that brought it the real accolades. There isn’t much you can go wrong with on the menu, from the artisan cheese plate and BBQ beet starters to the “surf and turf” pho and absolutely epic burger. They also do a robust weekend brunch (10am-2:30pm, Saturday and Sunday). This is a classy joint, and you’ll eat well no matter when you go.

Uinta Brewing Co (Salt Lake City)

Everything about Uinta Brewing Company is a celebration of the Beehive State. Their Cutthroat Pale Ale, Bristlecone Brown, King’s Peak Porter, and Golden Spike Hefeweizen are named after the state fish, state tree, the highest mountain in the state, and the commemorative completion of the transcontinental railroad (respectively). It would almost be tacky if the beer wasn’t so good. Brewmaster Kevin Ely has won more awards than he can count from critics and, perhaps more importantly, the citizens of Beer Advocate (the largest community beer-rating site on the web) have dubbed them “world class.”

The dedication to the hometown doesn’t end with eponyms. Uinta, named for the northeastern Utah mountain chain, is committed to preserving the landscape it draws from — the company’s breweries and brewpubs are powered 100% by wind and solar. Utah’s got that to spare, so they’ll be pumping out great beer for a long time coming.

J&G Grill (Park City)

When Jean-Georges Vongerichten, world-famous chef and winner of the 2009 James Beard Award (the Oscars of the cooking world), set up shop in Park City, the ski town went predictably mad to try the amazing food. And by all accounts, the project has lived up to the hype — this is a fabulous dining spot.

What you might not know is that, while Jean-Georges founded J&G Grill and put his name on the sign, the person manning the knives in back is usually Shane Baird, the unsung hero of Park City. He and Jean-Georges collaborate often enough, but Baird puts his own signature on the menus he creates, following principles of slow-cooking and farm-to-table freshness with an Asian flair.

If you’re after a truly high-class experience, see if you can score the Chef’s Table, a 10-seater overlooking the Deer Valley ski runs. But every table in the restaurant captures the warmth of the grill, and every patron orders off a menu with such heavy hitters as poulet rouge and beef tenderloin, along with more delicate dishes such as tuna tartare, chilled watermelon gazapacho, Maine mussels, and slow-cooked Shetland salmon.

Sunset Grill (Moab)

Sunset Grill sits atop a cliff overlooking the red rock canyonlands of eastern Utah. Such a prime location didn’t come cheap — the building is the old home of Charlie Steen, the man who put Moab on the map. A down-on-his-luck geologist, Steen discovered uranium in the local bedrock at the height of the Atomic Age, and he relished in the proceeds by purchasing an entire mountain on which to build his dream home — the dream home that would become Sunset Grill.

The Claytons turned the home into a restaurant back in 1993, though the vestiges of Steen’s vision remain. The history of the building is an all-American success story, and the menu reflects that with dishes almost entirely in the American Western style — Texas ribs, Idaho potatoes, chicken and grilled vegetables. But the real highlight will always be the stunning view. The dining room sits in the best part of the building, and with all of Moab before you, you won’t be looking at your plate while you eat.

Epic Brewing Company Tap-less Tap Room (Salt Lake City)

2008 saw the convergence of a multi-talented team in central SLC. Entrepreneurs David Cole and Peter Erickson partnered with head brewer Kevin Crompton to form Epic Brewing Company. And ever since, they’ve been living up to the name by creating exclusively high-alcohol beers, always striving for higher ABVs and taste profiles.

Epic distributes nationally, but the best places to sample these unique brews is from the source: the Epic Tap-less Tap Room, located right at the brewery. Order a simple sandwich or salad, or grab a meat + cheese board for the table, and wash it down with one of Epic’s numerous bottle offerings, which run the gamut from lagers, IPAs, and other classic styles, to more adventurous smoked, imperial, and fruit-infused labels.

The Red Iguana (Salt Lake City)

Fried iced cream at the Red Iguana. Photo: vxla

The Red Iguana isn’t particularly impressive looking. The sign is old and fading, the tablecloths look more like 1950s drapes, and on a quick drive-by it could easily be mistaken for some run-of-the-mill burrito slinger. But the hallmarks of years past exist because the restaurant is old, relatively unchanged since Ramon and Maria Cardenas first opened the doors back in 1985. It’s a Utah institution.

The founders immigrated to America from Chihuahua, Mexico in the ‘60s, setting up in Salt Lake to chase the American dream. That endeavor has grown to include over 150 employees (many of them immigrants themselves), while still keeping the family feel. That’s deliberate. Heritage is important to the Cardenas family — both past and future. Since Maria’s death and Ramon’s retirement, their daughter, Lucy, and her husband have taken over, and under that old and fading sign outside, they still cook the same family recipes passed down from Chihuahua.

People form long-lasting relationships with neighborhood favorite taco shops. At this point, the Red Iguana is as much a part of the Utah landscape as any sandstone arch. So while the Cardenas may try to keep the restaurant family-oriented, their family has grown to include a few million people by now. Their heritage, their legacy, is Utah.

This post was proudly produced in partnership with Utah, home of The Mighty 5®.

September 21, 2014

Hurricane Odile damages Mexico

Follow Matador on Vimeo

Follow Matador on YouTube

I REMEMBER RETURNING TO MY APARTMENT a few days after Hurricane Sandy; it looked as though someone had set off a bomb in my one-bedroom home. I cried more than I want to admit, and the recovery period seemed never ending. I am definitely more sensitive to events such as this, and my heart goes out to the people affected by Hurricane Odile, which hit areas of Baja California on September 14, 2014.

Stories by stranded American travelers are starting to emerge; I could tell that the situation was terrifying, and the emotional damage very present. Lines at the international airports for emergency charter flights were over a mile long, and passengers had to wait outside on the tarmac in the hot sun for hours.

But what really concerns me is the state of the locals in these areas. While the vacationer experience seemed harrowing, at least they have a places to go back to; many residents of Cabo will have damaged homes, or become homeless, and will be out of work while the resorts begin an arduous recovery period.

Please take some time to think about how you can help relieve the stress inflicted on these areas of Mexico. Matador will post helpful resources as we collect them:

Matador Network's Blog

- Matador Network's profile

- 6 followers