Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s Blog, page 246

October 4, 2019

The Weirdest Deer-Like Creatures Of All Time

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

If you think about it, deer are uniquely bizarre creatures. Unlike any other group of animals, they grow pointy bones atop their heads that fall off every year and then grow back. They adapt well, survive in a variety of conditions, and can outrun most predators. The deer of today range in size from the mighty moose, which can grow up to 1,500 pounds, to the pudu, which never grows larger than a Boston terrier.

However, as strange as modern deer are, their extinct cousins and other deer-like creatures are often even weirder.

Megaloceros giganteus, the Giant Deer

M. giganteus is the most well-known of the Megaloceros genus, and it’s the most impressive, too. M. giganteus had bigger antlers than any animal ever discovered, growing up to 12 feet from tip to tip! The antlers were wide and flat, or “palmated,” like those of a moose.

This animal is also known as the “Irish Elk,” although it is not as closely related to modern elk as it is with other modern deer species.

Even thousands of years ago, this animal impressed humans. It is believed that there is a painting of an Irish elk in the Lascaux caves. The images in those famous caves came from early humans who lived in modern-day France around 15,000-17,000 BCE!

Tsaidamotherium, the Almost-Unicorn

Is that a mythical beast with magical powers? No, it’s Tsaidamotherium! There are two species in this genus—both of which we know from very few fossil remains. In these species’, one horn is huge, centered at its forehead, and the other is tiny, barely noticeable. At first glance, you might think that it only had the one!

Tsaidamotherium is not a deer, but was more closely related to the modern musk ox. Deer, cattle, camels, and giraffes are all in the same group of animals called an “order.” Their order is “cetartiodactyla,” which includes all hooved animals with an even number of toes, as well as whales.

Hoplitomeryx – Going Overboard with Horns

If two horns aren’t good enough, how about five—and a long set of fangs? Check out Hoplitomeryx—an extinct genus of deer that lived in what is now part of South Italy.

Hoplitomeryx had horns, not antlers. Horns are bone covered in keratin—the hard substance that makes up claws and nails. Antlers are bones that fall off and grow back annually, and they usually branch off. Early deer like Hoplitomeryx had horns, but modern deer have antlers.

Imagery via Wikipedia || Life reconstruction of Hoplitomeryx by Mauricio Antón

Eucladoceros dicranios, the “Bush-Antlered Deer”

Based on the awe-inspiring branches of antlers, you might mistake this animal for Xerneas, the mythical stag Pokémon.

Eucladoceros was nearly as big as a modern moose and had peculiar, many-branched antlers, which could split into as many as twelve “tines,” or points, per antler. That should win some prizes at any hunting competition!

Photo via Wikipedia || Taken at Museo di Paleontologia di Firenze by Ghedoghedo

Synthetoceras, with a slingshot on its nose

The scientific name of this species, “Synthetoceras tricornatus,” means “combined horn, three horn.” It’s named for the horns on top of its head as well as the unusual protrusion on its snout.

This species was short but robust, and only the males had head decorations. It was a member of the family Protoceratidae, which included many other bizarre creatures with unusual horns and fangs.

Imagery via Wikipedia || Photo by Ryan Somma

The past is full of surprising creatures from giant versions of animals we have today, to animals with long tusks and fangs. Deer, antelope, cattle, giraffes, and their relatives are no exception. It leaves us to wonder about the thousands of species that have yet to be discovered.

By Kristin Hugo, contributor for Ripleys.com

Kristin Hugo is a science journalist with writing in National Geographic, Newsweek, and PBS Newshour. She’s especially experienced in covering animals, bones, and anything weird or gross. When not writing, Kristin is spray painting, and cleaning bones in her New York City yard. Find her on Twitter at @KristinHugo , Tumblr at @StrangeBiology , and Instagram at @thestrangebiology .

CARTOON 10-04-2019

October 3, 2019

Are Houseflies Really Only Abuzz For 24 Hours?

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

If you’ve ever had a fly buzzing around your home — and who hasn’t? — you know how frustrating this can feel. Fly swatter in hand, you rip your house apart attempting to get at the annoying insect who manages to stay just out of reach. At least you can rest secure in the knowledge that it’ll be dead within 24 hours. Right?

Think again!

Rumor has it that houseflies (Musca domestica) are a very short-lived pest in the common household, but it turns out these little insects have more than a mere 24 hours to eke out their lives, steal a little food, and pass on their genes to the next generation of maggots. According to entomologists, houseflies live for upwards of 20 to 25 days. What’s more, in some instances, they’ve been documented to live for up to 30 to 60 days!

The Intricate Life Cycle of a Housefly

Like other types of flies, the common housefly goes through an intricate life cycle that involves a variety of stages. Remember The Fly (1986) or The Fly II (1989)? Neither one of those nasty transformations happened overnight either.

The fly life cycle starts with a female housefly laying eggs that look like tiny grains of sand. On average, each female can lay 150 eggs at one time, and she does so on rotting wood or flesh. These eggs hatch into nasty white larvae known fondly as maggots. Maggots have ferocious appetites and devour every unsavory thing you can imagine, growing fatter and fatter in the process. The larval stage can last anywhere from a few hours to a couple of days. Then, they enter the “pupal” phase.

During the pupal phase, maggots go through a fundamental structural transformation. Their skin changes from white to red, black, brown, or yellow, and their bodies lose their cylindrical shapes. They grow hardened outer casings. Not to be confused with cocoons, these shells allow the maggots to lay dormant while more changes happen.

While chilling in their shells, they develop legs, wings, and all of the other features associated with the common housefly. Once the process is complete, the fly breaks free of the casing and embarks on a search for food and a mate so that they can start the life cycle all over again.

It’s a Fly’s Life

How long does the transformation take from birth to fly “dating”? According to the World Health Organization, it requires six to 42 days for a fly egg to develop into a fully functional adult. The pupal stage alone takes between two and 10 days, and adult flies need a few additional days before they can reproduce.

Why the large variation in timeframe? The life cycle ultimately comes down to ambient temperatures.

In both the larval and pupal phases, they can overwinter in protected areas such as manure piles, and the process can drag on for up to two months. But in optimal summer conditions with warm temperatures, flies complete their life cycle in little more than seven to 10 days.

This can translate into nasty infestations. For example, in temperate regions, as many as 10 to 12 generations may occur each year. This skyrockets to 20 generations in subtropical and tropical regions.

The 24-Hour Fly Myth

In Pixar’s A Bug’s Life, a disgruntled housefly exclaims, “I’ve only got 24 hours of living, and I ain’t gonna waste ‘em here!” While it makes for a hilarious line, common houseflies live much longer than 24 hours as you can see by the intricate life cycle outlined above.

So, how did this whole myth get going in the first place?

More than 120,000 different species of flies exist in the world. Of these, 3,000 species are known as mayflies. After living aquatically as larvae known as nymphs or naiads for one to three years, mayflies emerge from the water with the sole goal of reproducing. They don’t even have functional mouths and perish within one to 24 hours.

What’s the takeaway from all of this? Keep that fly swatter handy. Just remember to leave those poor, love-crazed mayflies alone!

By Engrid Barnett, contributor for Ripleys.com

The Hottest, Weirdest and Most Dangerous Craft Beers

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

For most of us, the burgeoning craft beer movement has been a wonderful thing—it has resulted in an abundance of inebriants across the board for nearly every flavor preference under the sun. But, while most of those new beer choices are most definitely a good thing, it’s also resulted in some pretty, uh, unbelievable creations. Grain, hops, yeast, and water are all it takes, right? Let’s take a look at just a few specialty brews making waves in the beer community with the addition of a few unorthodox ingredients.

Party Like Animals

Although most traditional beer recipes tweak hop varieties, grain measurements, or yeast strains to concoct new and tasty beers, some are created with more than a little help from the animal kingdom. Bull testicles and a smoked pig’s head? And, don’t be chicken: even old-world “cock ales” were rumored to include an entire bird, complete with mashed-up bones. Thankfully, there don’t appear to be any of those commercially available at the moment.

Take a gander at the following, and let us know which might be migrating to your must-try list:

Un, Kono Kuro (Sankt Gallen), whose not-so-secret ingredient is coffee beans—plucked from fresh elephant dung.

The Sunday Toast (Conwy Brewery), created with juices from slow-roasted lamb.

Porter Cochon (Earth Eagle Brewing) is reported to boast a wonderfully smooth mouthfeel, and that might be thanks to its key ingredient: smoked pig’s head.

Rocky Mountain Oyster Stout (Wynkoop Brewing Co.), made with nothing less than bull testicles.

Hvalur 2 (Stedji Brewery) also utilizes testicles, but this time from a whale! They’re smoked in sheep’s dung and Hvalur 2’s brewed up but once a year.

Photo by Steffi Grado, courtesy of Wynkoop Brewing Co.

“These Go To 11”

Taking things up a notch with a handful of peppers has long-been the culinary world’s go-to for innovative dishes, and brewers the world over are no different than kitchen crews when it comes to pushing the envelope with a handful of potent peppers.

Sriracha Hot Stout Beer (Rogue) is the only one endorsed by Huy Fong Foods, creators of the infamous Sriracha hot sauce. The brewer tells us to expect “rich notes of caramelized malts that give way to a warm, slow burn on a smooth finish.”

Photo courtesy of Rogue Ales & Spirits

Ghost Scorpion Lager (Elevator Brewing Co.), is made with two of the spiciest chilis in the world: the Bhut Jolokia (or Ghost chile) and the Trinidad Scorpion chile.

Smoked Porter (Stone Brewing Co.) credits its fiery flavor to chipotle peppers.

Ghost Face Killah (Twisted Pine Brewing Co.) is produced with six varieties of chile—including the infamous Bhut Jolokia, or ghost pepper.

“Utter agony for most, but absolute euphoria for a fiery few,” they proudly proclaim.

More to Pour

Spicy peppers and animal organs are hardly all there is to explore in the world of out-there beers, and we can’t help recommending Brewmeister’s Snake Venom to our most seasoned drinking pals. At 67.5% ABV, it’s the world’s strongest beer, so consider drinking this one from a shot glass. And don’t forget about Pisner—uh, that’s not a typo—another beer that gives us pause… it’s a beer made from barley fertilized by over 50,000 gallons of urine collected at 2015’s Roskilde music festival. Kudos to the fine folks at Norrebro Bryghus for celebrating the year that Sir Paul McCartney and Run the Jewels topped a star-studded list of visitors to the Danish music festival.

Curious yourself? It takes guts to belly up to the bar when exotic beers are on tap. Sometimes, it takes even more than that to make them.

By Bill Furbee, contributor for Ripleys.com

Source: The Hottest, Weirdest and Most Dangerous Craft Beers

CARTOON 10-03-2019

October 2, 2019

CARTOON 10-02-2019

October 1, 2019

What’s Inside An Exploding Dye Pack?

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

A dye pack is a radio-controlled incendiary device used by banks to foil a bank robbery, causing stolen cash to be permanently marked with dye shortly after theft. In most cases, a dye pack is placed in a hollowed-out space within a stack of banknotes, usually $10 or $20 bills.

This more “modern” example of a security pack feels like a bundle of $20s in hand rather than the original, rigid design. Nearly impossible to find, these security packs are coveted by US bill collectors.

When a bank robber left the building with one of these packs hidden among other bills, it would explode. The dye would stain the other bills, and often even the criminal, with a permanent dye. This allowed stolen bills and accompanying criminals to be easily identified.

Some of these security devices didn’t fire automatically. They housed a radio transmitter to help track bank robbers.

This security pack was made using 200 real twenty-dollar bills, meaning the bills alone were once were $2,000. After being hollowed out to accommodate the electronics, these bills are no longer usable as legal tender.

To date, dye packs have been credited with catching over 2,500 criminals and recovering over 20 million dollars in stolen money.

Dye packs can be quite dangerous when armed. Because of this, many banks reserve their use just for hold-ups, placing them nearby tellers to add to cash during a robbery. The explosion of the dye pack can reach temperatures of nearly 400 degrees Fahrenheit, burning a robber should they try and tamper with it. Some security packs were even loaded with tear gas to further incapacitate criminals.

The exploding dye pack in the Ripley collection has been safely disarmed, though some black ink residue is visible on the electronics and casing.

Surviving Multiple Lightning Strikes – Ripley’s Believe It or Notcast Episode 17

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

While the myth of lightning never striking twice has been perpetuated for years, meteorologists have long debunked the idea as nonsense.

This week on the Notcast, we explain why lightning can and will strike twice. We also examine the lives of two people who thought they were cursed after being struck by lightning several times throughout their lives.

Roy Sullivan’s appearance in the Ripley’s cartoon.

For more weird news and strange stories, visit our homepage, and be sure to rate and share this episode of the Notcast!

Source: Surviving Multiple Lightning Strikes – Ripley’s Believe It or Notcast Episode 17

CARTOON 10-01-2019

September 30, 2019

How One Man Survived 20 Venomous Snake Bites

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

Throughout the course of his snake-handling career, Bill Haast has received hundreds of snake bites—2o of these encounters nearly killed him. For a normal man, these fatal experiences may have meant inevitable death. But, Haast survived each fang by routinely injecting himself with venom for more than 60 years in order to build up his immunity.

Haast was born in 1910 and became interested in snakes at an early age. After getting married and raising a family, he opened the Miami Serpentarium, which produces snake venom for medical and research purposes. Between 1947 and 1984, he ran the facility as a tourist attraction and extracted venom from reptiles, including king cobras, in front of crowds of people up to 100 times a day. Haast would grab the snakes under their heads and drain the venom from their teeth into test tubes.

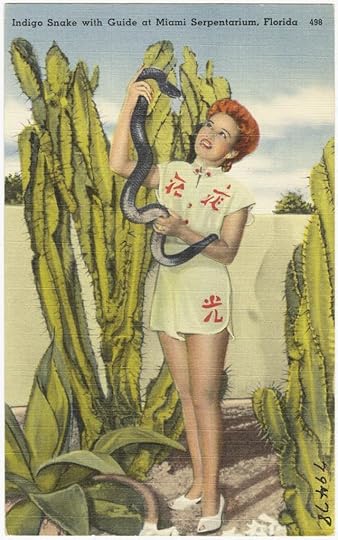

Postcard of Indigo snake with guide at Miami Serpentarium, Florida || CC: Boston Public Library

The snake handler estimated that he handled over 3 million poisonous snakes over the course of his lifetime, according to his obituary. Haast did everything he could to avoid being bitten, yet the sheer number of snakes he handled inevitably led to a bite now and then. By 2008, he had been bitten at least 172 times. During one of these encounters, his wife was forced to cut off his fingertip with garden clippers after a cottonmouth got a little too feisty.

In 1948, Haast started injecting highly diluted cobra venom into his body each week, eventually adding over 30 different types of venom into the mix in order to become immune to their venom. He even donated his blood to help other snakebite victims—21 to be exact. After aiding a young boy in Venezuela, the country made him an honorary citizen for trekking into the jungle to give the child a pint of his blood.

Haast, however, was not immune to all snake bites. In 1989, the Associated Press reported that the White House used its contacts in Iran to locate a rare antivenom to treat Haast after he was bitten by a Pakistani pit viper.

The world’s most famous snake handler passed away in 2011 at age 100 from natural causes.

The History of Antivenom

One of Louis Pasteur’s protégés, Albert Calmette, created the first antivenom in 1896. He injected horses with venom and then collected the antibodies to develop antivenom.

An estimated 7,000-8,000 people are bitten by venomous snakes in the United States each year but less than one percent die, if they receive proper treatment. The common culprits are eastern diamondback—common in the southeast—and western diamondback rattlesnakes—common in the southwest.

But, even snake experts have fallen victim to venomous bites. American herpetologist Karl P. Schmidt died in 1957 after being bitten by a juvenile snake he acquired at Chicago’s Lincoln Park Zoo. The reptile, a boomslang, bit Schmidt on his thumb while he was processing it. Falsely believing it was a nonfatal dose of venom, Schmidt documented his symptoms, which included, nausea, fever, chills, and bleeding from his nose and mouth. He died within 24 hours from respiration paralysis and a brain hemorrhage.

A Venomous Price to Pay

In recent years, snakebite victims have been billed hundreds of thousands of dollars for antivenom. The wholesale price is currently $2,500 per vial, and patients can require sometimes dozens of bottles to recover.

In 2016, Dominic Devine, 10, was bitten by a venomous snake in Lake Mathews, California. His parents were initially billed $1.18 million for the treatment before the cost was reduced to $350,000 after an accounting error was uncovered.

One year earlier, Todd Fassler was bitten by a rattlesnake while attempting to take a selfie with it at the Barona Speedway racetrack in Lakeside, California. He received a bill for $153,000. In 2012, A UC San Diego exchange student from Norway was snapped by a rattlesnake and socked with a $143,989 hospital bill.

One reason why antivenom is rather costly is that only one brand—CroFab—is currently available on the American market. Antivenom is created by injecting sheep with snake venom and collecting the resulting antibodies created by the animal’s immune system. The manufacturing process is only one-tenth of one percent of the total cost, according to the American Journal of Medicine. The inflated price is due to clinical trials, legal costs, hospital fees, and regulatory constraints.

Collection of snake venom

The good news is that a few years ago the FDA approved a new antivenom called Anavip to treat rattlesnake bites. It is scheduled for release in the United States in October 2018 and is expected to be a cheaper alternative.

Making Hiss-tory in Pain Relief

Haast came up with the idea to use venom to treat various illnesses, including polio, arthritis, and multiple sclerosis. Scientists have developed two pain relievers containing elements of snake venom—Cobroxin and Nyloxin. These homeopathic products are used to treat a variety of problems including angina, asthma, headaches, back pain, and other maladies. These medicines are for those seeking alternatives to opiate-based analgesics.

There is also a medicine called Viprinix, also known by its generic name ancrod, which is derived from pit viper venom and is intended to be used as an anticoagulant. Doctors discovered the healing properties of the venom after realizing victims of Malayan pit viper bites did not clot “normally” for several days following an attack.

Researchers have studied its effect on stroke victims as well as those suffering from deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary hypertension, and other conditions. While Viprinix has undergone several clinical trials, it is not currently approved for medical use in any country.

By Noelle Talmon, contributor for Ripleys.com

Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s Blog

- Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s profile

- 52 followers