Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s Blog, page 236

November 22, 2019

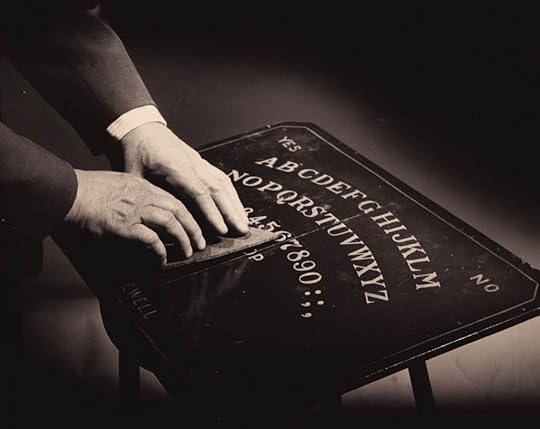

Tapping Into Our Second Intelligence With The Ouija Board

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

Here’s the headline: Woman waits 15 days to bury her dead mother in the backyard. Your mind may have resorted to blaming some kind of mania or mental disease for this bizarre act. But, apparently, neither of these things played a part in keeping a corpse around the house as a conversation piece. In the midst of being sent to a psychiatric ward, this disgruntled Chicago woman blamed her actions on the commands of the Ouija board. But, is the Ouija truly to blame? Is it at the fault of the spirits from beyond, or is it all in our heads?

If you’re unfamiliar with the Ouija, it’s usually a wooden board, complete with numbers, the alphabet, the words Yes and No, and a simple “Goodbye.” Typically played with a group, or sometimes independently, the players rest their hands on the moveable planchette at the center of the board. The response to any question is answered by the planchette’s movement.

Photo courtesy of the Talking Board Historical Society

Beyond the spiritual realm, is there room for another explanation for this movement? One that may only be explained by the unexplainable? Science points to “Yes.”

Research has shown that human beings actually have some kind of second intelligence—one that can only be accessed under the right conditions. This phenomenon is called the Ideomotor Effect, and it basically explains how and why we make movements without even realizing we’re making them.

“Most people think they have complete control of their minds, but they are wrong,” says Ron Rensink, an associate professor of computer science and psychology. “The truth is, we perform thousands of unconscious mental and physical tasks every day.”

A study by the researchers at the University of British Columbia tested this phenomenon using the Ouija board as a primary tool. Participants were asked, verbally, to answer questions to the best of their ability, and they were right—about half the time.

Following the verbal portion of the test, participants were given a partner, blindfolded, and instructed to allow the planchette to freely roam across the Ouija board to reveal an answer. Without the participant’s knowledge, when questions were asked, their partners removed their hands from the planchette, meaning that participants were playing alone.

When these subjects answered the same questions using the Ouija board, they answered correctly upwards of 65 percent of the time—a result of believing that the answers were coming from someplace other than their common knowledge.

Baffled by the dramatic difference of these results, the UBC is eager to run more studies surrounding our subconscious responses and decisions. But, to no surprise, accessing these areas of our brain and thought is no easy feat. Rensink calls the field of research related to our unconscious mind “terra-incognita,” and he refers to it as “the iceberg lying largely beneath the surface.” There are very few ways to investigate the depths of our minds, but researchers and scientists, like those at the UBC, are working diligently to develop more of these techniques.

Photo courtesy of the Talking Board Historical Society

The truth of the matter is, many of our everyday actions are done somewhat on auto-pilot leaving us to wonder what lies in the depths of our brain that even we don’t have access to ourselves. But, whether you’re a believer in science and the subconscious or the spirits and spells, one thing holds true—the Ouija world is truly unexplainable.

Source: Tapping Into Our Second Intelligence With The Ouija Board

Did The Pilgrims Really Wear Black, White, And Buckles?

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word “Pilgrim”? Perhaps, dour-looking early Americans sporting black-and-white clothes accessorized with buckled hats and shoes? This image of the first colonists to New England—popularized in the 19th-century—is based on a 1651 portrait of Edward Winslow, third governor of the Plymouth colony. But is it based on historical accuracy?

Not so much.

Pilgrims loved their colors as much as we do today. They wore everything from green to red and orange, only limiting their choices based on the natural dyes available to them. Read on to find out how the color-craving ladies and gents aboard the Mayflower actually dressed.

Color Me Fabulous

While we tend to think of the Pilgrims as the kind of folks that Johnny Cash, “the man in black,” could’ve swapped shirts and pants with, color was a surprisingly common element of even the most devout Pilgrim’s clothes chest. Both women and men enjoyed a broad palette of colors, from browns to russets, greens to yellows. Scarlets and lavenders also proved popular colors for various items, from caps to petticoats.

How do we know this? From examining the Pilgrims’ detailed probate records. For example, one Plymouth colonist, Mary Ring, died in 1633 leaving behind some of the following garments:

White stockings

Blue stockings

A red petticoat

A violet petticoat

Three blue aprons

Two violet waistcoats

A “mingled-color” waistcoat

Ring also owned blue and red cloth at the time of her death, presumably to make more colorful clothes. And she was no lone rainbow-colored rebel. When William Brewster, one of Plymouth’s church elders, died in 1644, he left behind green pants, a violet coat, a blue suit, and a red cap. Like Ring, Brewster was no one-color wonder.

William Bradford, who served five non-consecutive times as Governor of Plymouth colony, listed among his possessions:

An old violet cloak

A light-colored cloak

An old green gown

A light-colored coat

A red waistcoat

Two hats, a black one and a colored one

A lead-colored cloth suit with silver buttons

If these estate lists are providing you with a new picture of what the first Thanksgiving looked like, that’s a good thing. The Pilgrims would’ve worn a wide assortment of clothes colored with dyes made from berries, leaves, and roots.

That Whole Somber Business of Black

The black-and-white palette that we see in so many Victorian-era depictions of Britain’s early New World residents says more about the Victorians than the Pilgrims. It speaks to their intense desire to romanticize the past and create an idealized esthetic around the Pilgrim’s spiritual belief in the daily struggle between the forces of good and evil.

What’s more, fashionable Victorians were obsessed with black and white. Paintings such as Edgar Degas’s Self-Portrait (1855) and Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street, Rainy Day (1877) illustrate this point. So, they dressed the Pilgrims in ways they found respectable.

The issue of what Pilgrims once wore has been further confounded by the tendency of later people to confuse Pilgrims and Puritans. In all fairness, it’s easy to see why so many people have made this mistake over the years. Yet, while both represented groups of religious reformers who landed in modern-day Massachusetts, they came to the New World at different times, motivated by different reasons, and defined by different social classes.

Pilgrims Versus Puritans

Pilgrims, or Separatists, lived apart from British society, driven out over religious conflict. As a result, no matter how educated they were, they subsisted at the bottom of the economic spectrum.

They never used the term “Pilgrims,” either. In fact, the association didn’t exist before 1800. Instead, the people who landed at Plymouth would have referred to themselves as “forefathers” or “first-comers.” Roughly 50 percent of them died within the first year of making landfall in North America. Without the help of the neighboring Wampanoag people, who taught them how to fish and farm, the colony might have collapsed altogether. Of course, this cooperation resulted in a feast attended by natives and new arrivals in 1621 that we still celebrate today while stuffing our faces around the Thanksgiving table.

Unlike the “first-comers,” Puritans never separated from the larger Church of England. As a result, they enjoyed high economic status. They displayed their wealth in a variety of ways, including melancholy black get-up that would make Severus Snape envious. While about 200 “first-comers” landed at Plymouth with more following in subsequent years, Puritans came in droves. When they founded Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1630, they brought along 17 ships carrying 1,000 passengers. They quickly swallowed up the 2,600 Pilgrims in the area, engulfing their colorful attire in an inky sea of buckled shoes and hats.

You see, black was among the most expensive dyes of the day, and buckles represented another audacious sign of wealth. The average Pilgrim proved too poor to wear either of these. But Puritans loved to show off in shades of ebony with prominent buckles.

Sure, portraits of Plymouth governors depict them in severe black suits. But it was commonplace to dress in your absolute best for a portrait sitting, the Baroque equivalent of prom pictures today. Of course, just as tuxes and evening gowns are inaccurate representations of how we dress, the austere black garments pictured in portraits offer little insight to Pilgrims’ daily wear. The same goes for the extravagant buckled accessories.

Over time, Puritans and Pilgrims became blurred in American history because they shared a similar back story. But while lavender cloaks and red petticoats would’ve been all the rage among the impoverished “first-comers,” the Puritans made black the esthetic standard. What’s more, Pilgrims forged a fascinating relationship with the Wampanoags, one that included fighting in battle together against the Wampanoag’s enemies. But the Puritans neither believed in religious tolerance nor cooperating with native peoples, which make them the antithesis of everything Thanksgiving should stand for.

By Engrid Barnett, contributor for Ripleys.com

Source: Did The Pilgrims Really Wear Black, White, And Buckles?

CARTOON 11-22-2019

November 21, 2019

Double Take! These Animals Have Two Faces

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

They say two heads are better than one, but what about two faces?

Craniofacial duplication, or diprosopus, is a rare condition that causes an animal to have a second face. It’s often fatal at or around birth, but some animals, like Frank and Louie, live out full lives. Other animals, including pigs, cattle, chickens, and even people have been born with double faces.

Such a deformity certainly results in quite a few head turns—but what causes it?

Scientists aren’t 100% certain of the exact mechanisms that cause diprosopus. Unlike conjoined twinning, craniofacial duplication isn’t the result of two fetuses merging in the womb. It’s more like one animal developing twice as much face as it was supposed to.

The Sonic Hedgehog Genetics

There is a protein called Sonic Hedgehog Homolog (SHH) that corresponds with a gene of the same . Experiments have shown that the SHH gene is extremely important in body development, including in the face and brain.

In an experiment published in the journal Development, researchers gathered fertilized chicken eggs and edited the embryos inside so that they had either not enough, or too much, SHH. The ones that didn’t have enough SHH generally had narrow faces, and sometimes they would even have just one, single eye in the middle of their face.

The embryos that had too much SHH had wider faces, and, in extreme cases even had parts duplicated. In chickens, that means extra eyes and beaks. People have seen this condition in pigs, cattle, cats, and people.

Life with Two Faces

An animal with two entirely separate heads has two brains, and, therefore, is two animals sharing one body. However, an animal with two faces and one skull is one individual—one brain controlling both faces. Generally, both sides move in unison, as they accept the same commands from the brain.

Being born with a second face is quite uncommon but, given the sheer volume of everyday births across the world, it’s bound to happen on the rarest of occasions. And, to no surprise, survival among the two-faced is even rarer. Many two-faced farm animals are stillborn, and farmers will sometimes quietly bury them without documenting their existence. Others will live a little longer, like Ditto the pig—Ditto is rumored to have died after eating with one mouth and inhaling with the other. Frank and Louie is the longest-lived two-faced cat, and he died at the ripe age of 15.

In nature, things don’t always go to plan. In the case of two-faced animals, sometimes we get a little more than what we bargained for.

By Kristin Hugo, contributor for Ripleys.com

Kristin Hugo is a science journalist with writing in National Geographic, Newsweek, and PBS Newshour. She’s especially experienced in covering animals, bones, and anything weird or gross. When not writing, Kristin is spray painting and cleaning bones in her New York City yard. Find her on Twitter at @KristinHugo , Tumblr at @StrangeBiology , and Instagram at @thestrangebiology .

CARTOON 11-21-2019

November 20, 2019

To The Land Down Under, In More Ways Than One

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

Up to nine feet of earthworm is a lot to wrap your head around, and Australia’s giant Gippsland earthworm—you might know it as Megascolides australis—is one of the world’s lengthiest wiggly worms. In fact, it even has its own dedicated parade.

“They live underground and have so many secrets,” Dr. B. D Van Praagh of the Building Capability to Manage Giant Gippsland Earthworm Habitat on Farms organization says. “It’s hard to get past their size; although often exaggerated, they are huge. While the average length is just over a meter, they easily reach two meters when relaxed.” What’s more, the giant Gippsland earthworm even makes its own unique sound. “When they move in their wet burrows, they make a gurgling sound that is very loud—it’s fascinating,” Van Praagh shares.

An extremely rare photo of the Gippsland earthworm flooded out of its burrow. The giant Gippsland earthworm is very vulnerable on the surface; it would most likely get picked off by predators or dried out from the sun over time. || Photo courtesy of Beverley Van Praagh

Van Praagh is a private consultant and specializes in threatened invertebrates, “mostly the giant Gippsland earthworm and burrowing crayfish in the South and West Gippsland region of Victoria,” she says.

Habitat of Giant Gippsland Earthworm || Photo courtesy of Beverley Van Praagh

Gippsland is located in a rural region of Victoria, Australia. There’s a human population of less than 300,000, and significantly fewer giant Gippsland earthworms; due to its small numbers and a slow reproductive cycle, the giant Gippsland earthworm is considered to be endangered.

“They live in an area of about 40,000 hectares—a hectare is equal to 10,000 square meters—but are very patchy within that area,” Van Praagh reports. So their exact population size is unknown.

As you might expect, an authority like Van Praagh has gotten the pleasure of meeting Megascolides australis up close and is thrilled to detail the experience.

“It’s a privilege to hold one, as so few people have,” she says. “They feel cold and slippery. They are very gentle and do not move around much at all when out of the ground. No squirming like other earthworms.”

Photo courtesy of Beverley Van Praagh

Curious? You’re not alone, and thankfully the town of Korumburra, about three hours away, has been known to celebrate the Giant Gippsland earthworm with pride. In fact, Korumburra has organized a number of worm-themed festivals in past years—one lucky lady would even walk home with the title “Earthworm Queen,” and there were plenty of games for the kids.

What’s more, there’s even a mascot, Karmai, with its own Facebook page. A wonder itself, the 148-foot pink Karmai took about three months to build from papier-mâché with the help of local schoolchildren. At one time, Karmai was the largest parade float of its kind in the entire world.

A fitting mascot for the giant Gippsland earthworm, we’d say.

Other Worrisome Worms

“There are other giant worms around the world,” Van Praagh points out, in “South Africa, China, Ecuador and other parts of Australia. But I think the giant Gippsland earthworm is the most well known and perhaps the best studied. (There’s) little information about other giant earthworms.” Care to guess why? “They’re difficult animals to study!” she admits.

In America, the Oregon giant earthworm, Driloleirus macelfreshi, is found in—you guessed it!—Oregon. Then, there’s the giant Palouse earthworm, Driloleirus americanus, which tends to hang out in Washington and Idaho grasslands; it was originally thought to have gone extinct in the 1980s but has been observed in the wild since. Although both the Oregon giant earthworm and giant Palouse earthworm are believed to only grow to just over three feet, that’s still plenty to marvel at.

You could say, it’s a whole lotta worm.

Check out Dr. B. D Van Praagh’s organization’s website for more on this giant earthworm.

By Bill Furbee, contributor for Ripleys.com

CARTOON 11-20-2019

November 19, 2019

Forrest Fenn’s Hidden Treasure – Ripley’s Believe It or Notcast Episode 24

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

After collecting rare artifacts for nearly 80 years, wealthy artifacts broker Forrest Fenn decided to hide a treasure in the Rocky Mountains. He released a cryptic poem, giving people clues as to where they could find it.

This week on the Notcast, we talk to two treasure hunters who have been chasing Fenn’s buried chest for years, then ask Forrest Fenn himself what motivated him to start such a prolific treasure chase.

For more weird news and strange stories, visit our homepage, and be sure to rate and share this episode of the Notcast!

Source: Forrest Fenn’s Hidden Treasure – Ripley’s Believe It or Notcast Episode 24

CARTOON 11-19-2019

November 18, 2019

CARTOON 11-18-2019

Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s Blog

- Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s profile

- 52 followers