Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s Blog, page 211

March 29, 2020

CARTOON 03-29-2020

March 28, 2020

CARTOON 03-28-2020

March 27, 2020

A Treasure Hunt For The Secret

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

What if we told you that, across the United States, there are eight opportunities to find buried treasure? Oh, and we have an entire book full of clues to help you find them. We’re going to let you in on a secret. But not just any secret, The Secret. The Secret is actually a book, and inside its pages, a real-life treasure map. But this isn’t your typical, “two paces to the left and stop when you see the waterfall,” kind of map. The Secret is a true puzzle.

Burying Preiss-less Treasure

In 1982, a publisher named Byron Preiss buried 12 casques in the ground of 12 different states. And, as one might imagine, no secret box secured in the earth is going to be easy to find. Each clue in Preiss’ book contains a drawing and cryptic message, leading to where one may be able to find said buried treasure. At the time of the book’s release, the treasure hunt was simply a publicity stunt. Preiss needed a way for the book to gain attention and build traction around the mystery of its pages. In doing so, he believed that the treasures would be found fairly quickly. But to his dismay, this wasn’t quite the case. To this day, 38 years later, only three of the 12 treasures have been uncovered. The first hit the surface just one year after The Secret was published. Then, the hunt went cold for 21 years until the second box was discovered in 2004 in Cleveland, Ohio. And the third and latest box was found just a few months ago by a family and group of construction workers, in Boston, Massachusetts.

Doing Some Digging

Let’s start with casque number one, discovered by three teenagers in Chicago, Illinois. While many Chicago locals would have a hard time decoding the image, these not-so-average Joes spend their time dissecting each piece of the intricate drawing. They saw beyond the illustrated windmill veins to its base—Chicago’s Water Tower. This structure, along with an upside-down Taurus (or Chicago Bull), the art institute’s Spirit of the Lake Statue, and the Illinois state outline were all key factors to discovering the location of their treasure.

The Secret, Image 5, depicting Chicago, Illinois

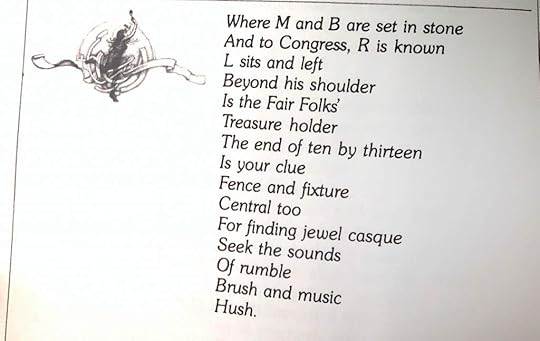

After solving the pieces of the illustrated puzzle, they began decoding the poem, attempting to make sense of the lines. With initial spring off point at the statue of Man and Beast (AKA M&B) on Congress Parkway, the boys were well on their way to buried treasure.

The Secret, Verse 12

You can only imagine how frustrating and rewarding this find must have been for these three young men, especially based on the complexity of their explanation. But it goes to show, this puzzle is solvable. The real question is, is it worth solving? Let’s talk about what all of the hard work and perseverance gets you, aside from a job very well done.

Preiss’ Prizes

Upon reaching your final destination—wherever you may believe it to be—your reward is located about two feet down in the ground. The lucky clink of your shovel is hopefully more than rock or rubble and instead resembles that of a plexiglass box. Inside this 8-by-8 encasement of plexiglass is a ceramic, closed bowl. And inside of this box, within a box, lies a key. A key to unlock a very shiny, valuable prize: Jewels! In each of the 12 illustrations, a different gemstone is hidden somewhere in the picture, alluding to what you will find buried in each city. For anyone who’s reading and thinking about the easy way out of this puzzle, we’ll stop you right there—there is no easy way. Unfortunately, Byron Preiss passed away in a car accident 15 years ago, taking the answers to our many questions with him. His daughters have provided great intellect and passed-along “fatherly” advice to hunters, but even they don’t know the treasures’ locations. The artist behind each of the 12 illustrations was a truly loyal confidant to Preiss. He burned all evidence, down to the original imagery from which he painted.

Lucky Number 4?

After discovering the gem (pun intended) that is The Secret, our team is setting out to be lucky number 4 in Preiss’ daring dozen. We’re headed to America’s oldest city—St. Augustine, Florida!

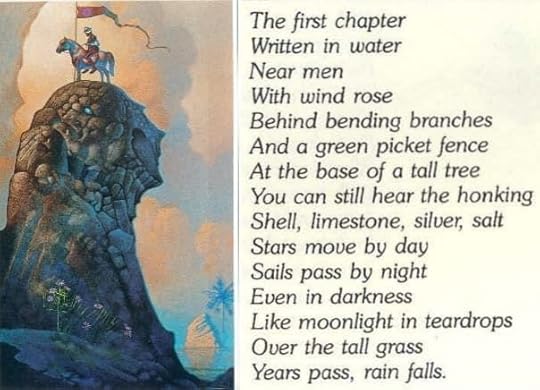

The Secret, St. Augustine verse and illustration pairing

Before traveling up the Florida coast to this historical stop, we did a bit of research on The Secret—read articles, analyzed past hunts, brushed up on St. Augustine history, and binged a few episodes of Expedition Unknown. Turns out, we’re not the first people to search for St. Augustine’s hidden Secret! Josh Gates and his crew of treasure hunters followed the clues to where they believed treasure number three might be hiding. But unfortunately, the only thing they dug up was dirt. Many treasure hunters believe that this page in the story leads them to The Fountain of Youth, but our team is convinced otherwise. Could another option be the grounds of… Ripley’s Believe It or Not!? While we are extremely hopeful that we do uncover the plexiglass square in Ripley’s backyard, it’s hard to be so sure after the many attempts and unlucky digs in St. Augustine. We need your help, Strange Things! Join our team as we hunt for buried treasure and be sure to leave your questions, theories, and ideas in the comments below.

EXPLORE THE ODD IN PERSON!

Discover hundreds of strange and unusual artifacts and get hands-on with unbelievable interactives when you visit a Ripley’s Odditorium!

Source: A Treasure Hunt For The Secret

CARTOON 03-27-2020

March 26, 2020

Debunking the Five-Second Rule

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

Have you ever dropped food on the floor? Then, rapidly lunged for it, trying to grab it before your five seconds were up? Maybe you even brushed it off for good measure before popping it in your mouth? Because limited floor time means limited exposure to bacteria, right? Wrong. You, my friend, have fallen prey to one of the oldest (and grossest) food handling rules in history.

The “Khan Rule”

How did the five-second rule get started? The first printed reference to eating morsels dropped on the ground within a proscribed length of time dates to 1995. That said, the foundation for this concept extends back into the annals of human history. In the book Did You Just Eat That? by food scientist Paul Dawson and food microbiologist Brian Sheldon, they blame the five-second rule on Genghis Khan.

The 12th-century Mongol leader enacted the “Khan Rule” at banquets. It went something like this. Food that fell on the floor was good to eat no matter how long it sat there. Why? Because any meals prepared for the Khan were good enough for his company. What happened to said victuals on the way from the kitchen to the plate proved of little consequence. (Chef Ramsey would have a field day with this…)

Portrait of Genghis Khan

Of course, it would be another six centuries or so before germ theory would start to develop in Europe and beyond. So, we need to give old Genghis a break. As far as the Mongols (and other medieval people) were concerned, dusting away visible dirt particles made food palatable once more.

Germ Theory and Potato Pancakes

In the 19th century, Louis Pasteur shocked the scientific world with his discovery of microorganisms critical to the fermentation of wine and the souring of milk. Germ theory evolved from there with the unsavory revelation that germs are everywhere.

Nonetheless, the “Khan Rule” has persisted in modern culture. A 1963 episode of Julia Child’s cooking show The French Chef, further canonized the centuries-old practice. While attempting to flip a potato pancake during one of her shows, Childs missed, and the pancake ended up on the stovetop.

There, the pancake sat for approximately four seconds before Childs tossed it back into the pan. Although further exposure to heat would help kill bacteria transferred to the surface of the pancake during the fall, people latched onto the idea of rapidly picking up food to “save it.” Even when re-heating proved out of the question.

Science Debunks the Five-Second Rule

In 2016, Professor Donald W. Schaffner, a food microbiologist at Rutgers University in New Jersey, announced the results of a two-year study into the sensationalized five-second rule. The conclusion? No matter how fast you rescue food that’s fallen on the floor, bacteria will contaminate it. The transfer of bacteria to a surface can happen almost instantaneously. No wonder the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) cite surface cross-contamination as the sixth most common contributing factor to outbreaks of food-borne illness!

Salmonella bacteria growing in a petri dish

That said, a few factors determine the amount of bacteria transferred from the floor to a food item. These include the consistency of the food, the texture of the surface, and the length of time the food remains on the ground. Schaffer, along with master’s thesis student, Robyn C. Miranda, used buttered bread, unbuttered bread, strawberry candy gum, and watermelon pieces for the experiment. They dropped each substance from a height of five inches onto surfaces containing bacteria similar to salmonella. The flooring types included stainless steel, wood, carpet, and ceramic tile.

After dropping food items onto each surface, they tested four contact times: one, five, 30, and 300 seconds. Each drop was replicated 20 times, resulting in 2,560 different measurements. The result? While there was some validity to the idea that food retrieved more rapidly from the floor contains less bacteria, no fallen food escaped contamination.

Dropping the Truth

The surface the food fell onto had an impact on overall bacterial levels. Surprisingly, carpet had the lowest transmission rate of bacteria compared to the other surfaces. Its raised topography diminishes the surface area for exposure.

The food’s consistency also played a significant role. After all, microorganisms don’t have legs. Instead of hoofing it onto a new surface, they need moisture to help them transfer. So, watermelon, by far, proved the greatest germ magnet. It’s worth reiterating that all of the food substances tested were contaminated during their falls. And, honestly, do you want to play around with any exposure to foodborne illnesses such as salmonella, E. coli, or listeria? We don’t think so.

The moral of the story? Just because germs are out of sight and out of mind, doesn’t mean you should pick up that dropped M&M (or anything else) and nosh on it. Instead, quit the mental countdown and find a trash can.

By Engrid Barnett, contributor for Ripleys.com

EXPLORE THE ODD IN PERSON!

Discover hundreds of strange and unusual artifacts and get hands-on with unbelievable interactives when you visit a Ripley’s Odditorium!

Source: Debunking the Five-Second Rule

CARTOON 03-26-2020

March 25, 2020

The Most Famous Horned Toad in Texas

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

In 1928, 31 years after a courthouse was built in Eastland, Texas, officials found a horned lizard in the cornerstone of the structure—still living! The critter had reportedly been buried there since 1897, alongside a bible and several official town documents.

According to local legend, the horned lizard was dropped inside the cornerstone “time capsule” just before it was closed for over three decades. A four-year-old boy named Will Wood purportedly captured a toad named Blinky and buried him in the marble block. He placed it there to test his father’s theory that horned toads have the ability to hibernate for 100 years.

The Travelling Toad

In the late 1920s when the town decided to build a new, larger courthouse, officials dug out the cornerstone with hundreds of people in attendance. That’s when they discovered the lizard, who was covered in dust. At first, he looked dead, but then he started moving.

Even today, locals insist that the story is true.

No one stopped to think that it was impossible for a creature to survive for over 30 years without food, water, or air. While horned lizards do hibernate during the winter, they only have a life expectancy of five to eight years.

The lizard, also known as a horny toad, was named Old Rip in honor of Rip Van Winkle, a character from a Washington Irving story who fell asleep and didn’t wake up for 20 years.

News of Old Rip’s resurrection spread rapidly, and the toad became so famous that Wood, the little boy who put Old Rip in the cornerstone, took the lizard on a tour of the United States. He lived in a goldfish bowl and subsisted on a diet of red ants.

At one point, the lizard met President Calvin Coolidge in Washington, D.C. Old Rip was so popular, gas stations gave their customers free toads in his honor.

Believe It or Not!, Old Rip even made his mark on television. The toad was purportedly the inspiration behind the cartoon character Michigan J. Frog, created by Chuck Jones. The singing and dancing frog used to be a Warner Bros. mascot.

Outlandish Hoax or Gospel Truth?

Old Rip died, from pneumonia, according to newspaper reports, less than a year after he incredibly sprung back to life on February 18, 1928. In lieu of burying the toad, officials embalmed him and put the critter in an open coffin with a velvet interior. He was then displayed in the lobby inside the courthouse.

Old Rip in coffin || Photo by QuesterMark via Flickr

Old Rip remained largely unharmed until 1962 when a Texas gubernatorial candidate held him up by a hind leg for a photo opportunity, and it snapped off.

Then in 1973, a toad-napper stole Old Rip, leaving a letter in his place. The note claimed that the entire incident was a hoax, and the kidnapper demanded that people come forward to tell the truth. But no one did, and another letter later arrived, pinpointing the location of Old Rip’s body in the country fairgrounds. The toad made its way back to the courthouse, but not everyone was convinced that he was the original Old Rip because he appeared more mummified.

As for horned lizards in general, they all but disappeared from Texas several decades ago.

Old Rip, either the original or the imposter toad, is still on display today, and he is Eastland’s most celebrated resident. The town hosts the Ripfest festival each year, and school children annually visit the courthouse and take an oath, swearing that the seemingly tall tale is 100-percent true.

By Noelle Talmon, contributor for Ripleys.com

CARTOON 03-25-2020

March 24, 2020

The Sideshow Corpse Hidden In A Fun House

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

We’ve all heard some form of this ubiquitous urban legend: an eerily lifelike (deathlike?) mannequin of a dead body hangs suspended from the ceiling of an amusement park haunt.

But, upon closer inspection, this particular prop that drew screams and snickers from scores of children turned out to be a little too real; for what they were dealing with was no average piece of horror decor. More than just a dead ringer, it was the genuine article—a long-dead, leathery corpse.

Stranger than Fiction

Apologies in advance for the nightmare fuel, but this macabre myth is 100% true. The body in question was discovered by an unsuspecting television crew and its violent and uncanny past was revealed after unearthing the bizarre contents found inside the dead man’s mouth.

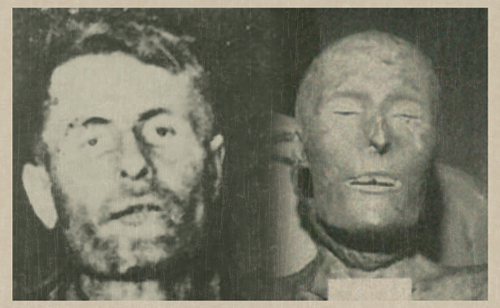

A wannabe Wild West gunslinger, Elmer McCurdy spent the last year of his life as an outlaw. His short-lived career ended after being killed in a drunken shootout with a sheriff’s posse. An unconventional life followed by an unremarkable death. But it was his afterlife that was truly bizarre. The well-traveled, mummified mountebank crisscrossed the country for decades while in the midst of decomposition. And people paid to see it.

The corpse of Elmer McCurdy in his coffin.

Unraveling the Truth

It was two weeks before Christmas of ‘76 and the cast and crew of The Six Million Dollar Man—an iconic television series of the seventies about an everyday astronaut-turned-crime-fighting-android—were filming on-location in Queen’s Park, Long Beach, California.

While producing an episode for its fourth season, Carnival of Spies, the crew were filming a scene with an evil German spy at odds with the bionic superhero inside of an existing funhouse. Scattered throughout were assorted automatic set-pieces triggered to deliver pop-up scares.

In between scenes, the art director attempted to stage an emaciated-looking dummy, spray-painted with glow-in-the-dark orange and adorned with a hangman’s noose. For four years, the antique had been hanging from the gallows, relegated to a back corner. The rush of rickety passenger carts sent it swinging back-and-forth through the otherwise still air. As it moved, there was a dry snap.

They didn’t have the technology to rebuild him, so the dummy’s brittle wax arm was separated from its ancient wax body.

Except the wax arm wasn’t made of wax. The hapless crewmember discovered this when they noticed that in the center of the accidentally-amputated appendage, was a human bone surrounded by muscle tissue. It was with dawning horror they realized that the oversized piece of beef jerky they were handling was actually the desiccated remains of a human being.

Dead Man’s Mouth

Production ground to a halt. Police and firefighters were called, who, in turn, contacted paramedics to report a severe case of dehydration.

The paramedics arrived and, upon seeing just how severe this case of “dehydration” was, burst out in uproarious laughter after discovering the corpse.

The petrified body was taken to a Los Angeles County coroner’s office, where it was determined that the cause of death was from a turn-of-the-century bullet jacket lodged in its chest. At one point an able-bodied man, the mummy had withered away to nearly a skeleton, shriveled down to a height of 5’3” and a paltry fifty pounds.

The body had sustained significant wear-and-tear, including wind damage resulting in the loss of several fingers, toes, and most of both ears, though it still maintained some wisps of hair—talk about dead ends. To accommodate the noose, a hole had been drilled through its neck, which seeped an unseemly yellow goo.

Initially, their only set of clues, to figuring out the life of this far-deceased man, were recovered from inside the body’s mouth—tickets to the Museum of Crime alongside a penny dated 1924. And with that, the secret behind this mummy’s mysterious saga, his antemortem career, and his postmortem life finally began to unravel.

Portrait of a Man

More pictures survive of Elmer McCurdy in death than those captured while living. The only existing photograph taken during his natural life is a grainy mugshot that depicts his front and side-profile with unkempt hair and beady eyes.

Born on New Year’s Day, 1880, McCurdy experienced a turbulent childhood—one that the likes of only Maury or Dr. Phil are equipped to handle. With all family either estranged or dead, turn-of-the-century economic downturn directed him westward. A drifter, looking to manifest his own destiny on the hinterlands, he undertook a revolving door of odd jobs that had a habit of getting botched due to chronic alcoholism.

McCurdy served in the U.S. Army for four years before settling in the Midwest. He gained a rudimentary understanding of nitroglycerin—the explosive element of dynamite—and rapidly proved that a little bit of knowledge is, in fact, a dangerous thing. Incapable of earning an honest living, McCurdy joined a cabal of crooks and committed a string of poorly executed bank and railroad robberies across the Great Plains.

Failed Frontiersmen

Literally every single one of his recorded safe-cracking endeavors ended in abject buffoonery. Tales of his legendary exploits include:

An arrest for public intoxication and possession of burglary implements, the latter of which he was able to get off by claiming the tools were needed to invent a “foot-operated machine.”

During a train heist, he overestimated how much nitroglycerin he should use, destroying a safe he believed to be holding $4,000. Instead, he made off with only $450 in melted silver.

Unable to ignite the fuse to open a bank’s vault, he scrambled to collect $150 in bags of coins.

After hiding in a farmer’s hayshed, he resurfaced to commit the heist of the century: robbing a train purported to be carrying $400,000. McCurdy robbed the wrong train. He made off with $46, two jugs of whiskey, and a handful of personal items he stole on the way.

McCurdy’s newfound frontier identity just wasn’t working out for him. While hiding out after the last railway foray, a $2,000 bounty had been put on his head. To make matters worse, his ability as a gunman was comparable to his prowess as a thief. On October 7, 1911, abandoned by his banditti with stolen whiskey in hand, McCurdy was tracked to a hayshed by three sheriffs and a pack of bloodhounds. He opened fire and an hour-long gunfight ensued. When the smoke cleared, McCurdy was down in the dirt and dead as a doornail.

Keep Calm and Embalm

Elmer McCurdy was a lousy crook. Which begs the question, how did this putz achieve enough notoriety to make the history books? By virtue of the incredibly bizarre Old West fad of putting dead bodies up for show.

Dating back to the Civil War, enterprising embalmers put unclaimed bodies on display at their mortuaries to not only help with identification but as an advertisement for their services. When nobody claimed McCurdy’s body in Pawhuska, Oklahoma, funeral director Joseph L. Johnson was horrifically determined to be compensated for his work.

The remnants of Elmer McCurdy were embalmed with an arsenic-laced ultra-preservative that would allow the body to last in a strikingly lifelike condition indefinitely. This was the norm at the time for the unclaimed dead, which left the preserved body waiting for its next of kin. Johnson decided that the most reasonable of all available options was to repurpose McCurdy as scenery for his funeral parlor, where he stiffly stood with a gun by his side, propped-up like a ficus for five years. He was posthumously billed as “The Bandit Who Wouldn’t Give Up.”

Johnson charged visitors five cents to see the dead man up close. Even worse, visitors paid their fare by inserting coins into McCurdy’s mouth. Though hardly the first funerary practice that saw objects placed in the mouth of the deceased, feeding McCurdy change like a coin-op arcade was certainly the tackiest. But this was not the only escapade his body was involved with during his residency at the Johnson Funeral Home. One alleged incident saw the undertaker’s children living it up Weekend at Bernie’s style, putting roller skates on McCurdy and rolling him throughout the house. Dead man walking rolling!

Carnival Con

Zany hijinks aside, McCurdy was proving to be quite the sensation. Word traveled fast of Johnson being in possession of an attraction that was drawing huge crowds at the box office. Carnival promoters from all over the country made offers to purchase McCurdy, but as far as Johnson was concerned his human taxidermy was not for sale.

After five years, a pair of men visited the mortician claiming to be Elmer McCurdy’s long-lost brothers there to give their kin a proper burial. They took Elmer to his homeland and he was finally laid to rest.

Just kidding. Elmer’s “brothers” were Charles and James Patterson, a pair of carnies who feigned bereavement to capture McCurdy’s carcass and take the sideshow on the road for the next six decades.

Hitting the Carnival Circuit

Elmer’s mass appeal should come as no surprise. Morbid curiosity about the effects of decomposition is naturally understandable, and, unless a given vocation called for it, people did not often have the opportunity to know what a dead body looked like before the days of the internet.

Cheaply-made dime novel melodramas—the precursor to pulp fiction magazines—were sensationalizing the myth of the American West. The heroes and villains of these tall tales were the stereotypical “silent, noble frontiersmen,” cowboys who doggedly pursued the “lawbreaking, mustache-twiddling, tie-a-damsel-on-the-railroad-tracks,” scoundrels in the name of frontier justice.

To take advantage of that, given an entertainment venture that immersed itself in all-things-lurid, what would be a better top-billing than a bona fide cowboy corpse? Or, at least, a cowboy-clad cadaver!

McCurdy found himself suddenly thrust into a sea of tents, fried food, cotton candy, rigged games, and screaming children on clunky rides. “The Bandit Who Wouldn’t Give Up” had more stage names than a luchador, variably coined as “The Outlaw Who Would Never Be Captured Alive,” “The Embalmed Bandit,” “The Famous Oklahoma Outlaw,” “The Mystery Man of Many Aliases,” and, finally, “The Thousand-Year-Old Man.”

Demand grew as McCurdy was swept across the country, further harmonizing his status as a drifter in both life and death. After he was done headlining at one of the traveling troupes of the Great Patterson Carnival Shows, alongside characters like the Strong Man, Alligator Girl, and the Torture King, McCurdy became part of a traveling Museum of Crime in 1922. Later, he joined the sideshow that accompanied the 1928 Trans-American Footrace.

Show poster for the Gentry Brothers Circus, who purchased the Great Patterson Show Circus in 1923.

Lost Memories and Hollywood Exploitation

Over the years, McCurdy would be pawned off from gig to gig; each time, both the body and memory of who he was further decayed. So, too, did the sideshow scene. Growing increasingly less lucrative as an exhibit, Elmer McCurdy answered the inevitable call of Hollywood.

Acquired as promotional material for the 1933 drugsploitation film, Narcotic, McCurdy was displayed in the lobby of movie theatres as an attention-grabber and a warning. Now mummified and beginning to shrink, his physical condition was credited as the result of being a morally bankrupt dope fiend.

McCurdy was periodically lent out, including to a traveling sideshow near Mount Rushmore where he sustained extensive wind damage, presumably from being transported on top of a truck like a Christmas tree. He was also a prop in the 1967 schlocky, carnival-themed horror film, She Freak. The following year he was sold in bulk to the Hollywood Wax Museum, who elected not to exhibit him due to the grotesque, rapidly deteriorating condition of his body.

It was around this time that McCurdy, having seen far better days, was forgotten to have ever been a person at all. Now, he was simply an artifact. Within a few years, he made his way to the Queen’s Park Laff in the Dark funhouse, waiting for a television crew to find him.

Last Rites

Elmer McCurdy’s biography is compiled with a bottomless pit of quirky contradictions that build upon the natural tension between life and death.

An admittedly enthralling story for all its peculiarity, it is easy to lose sight of the fact that McCurdy was more than a profitable sideshow exhibit or historical oddity. This prop was the vessel of a troubled soul who, like all of us, once had hopes, dreams, and the capacity to love and be loved. Sometimes it takes the spectacle of a traveling, rotten shell of a corpse to remind us of our own capacity for a disquieting lack of humanity.

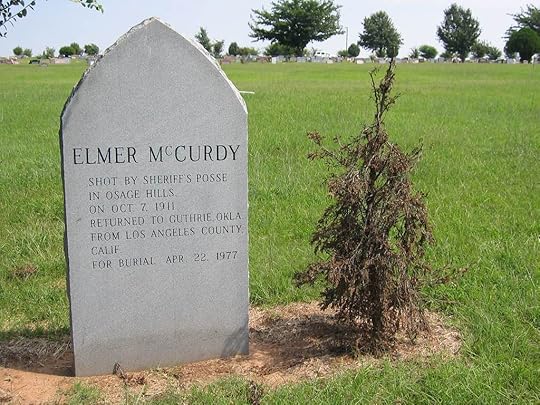

After his discovery and subsequent identification, the lawbreaker was finally laid to rest in the spring of 1977. Interred in Guthrie, Oklahoma, his requiem was attended by over three hundred spectators. There, laid next to actual Wild West outlaw Bill Doolin, whose body had once been exhibited alongside McCurdy’s, his grave was covered with several feet of concrete to prevent any further unauthorized exhumations or desecration.

There he remains, enjoying a well-earned rest. Presumably, at least. Now retired from show-business, his tale ends where it always belonged: the crypt.

Courtesy of Allison Meier via Flickr

By Kris Levin, contributor for Ripleys.com

Kris Levin is a traveling storyteller, professional wrestling referee, and Locker Room Detective. He can be seen internationally as television wrestling’s most junior official, #KidRef, and on social media at @RefKrisLevin

EXPLORE THE ODD IN PERSON!

Discover hundreds of strange and unusual artifacts and get hands-on with unbelievable interactives when you visit a Ripley’s Odditorium!

The Nazi Scientists Who Built America’s Space Rockets

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

After the War in Europe ended with the fall of Berlin, allied nations began using any means necessary to bring on Nazi scientists to enhance their own military technology.

This week on the Notcast, we explore Operation Paperclip, a covert project to bring former Nazi scientists that could have been tried for war crimes to the U.S. in order to build America’s space powers.

For more weird news and strange stories, visit our homepage, and be sure to rate and share this episode of the Notcast!

EXPLORE THE ODD IN PERSON!

Discover hundreds of strange and unusual artifacts and get hands-on with unbelievable interactives when you visit a Ripley’s Odditorium!

Source: The Nazi Scientists Who Built America’s Space Rockets

Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s Blog

- Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s profile

- 52 followers