Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s Blog, page 204

May 3, 2020

CARTOON 05-03-2020

May 2, 2020

CARTOON 05-02-2020

May 1, 2020

Why Did 17th Century Plague Doctors Dress Like Birds?

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

During the 17th century, Europe lay in the grip of a living nightmare. For three centuries, intermittent bouts of the Black Death (Yersinia pestis) swept across the Old World. Each surge further contributed to a death toll in the hundreds of millions. A seemingly unstoppable pandemic, victims faced excruciating symptoms. These symptoms included blackened skin, grotesquely swollen lymph nodes, and bleeding from the mouth and nose.

Attending doctors proved poorly equipped to deal with this pandemic. The disease re-visited the population generation after generation, indiscriminately killing. Without an understanding of germ theory and bacteria, physicians couldn’t effectively fight the disease. Instead, they relied on an admixture of superstition and anecdotal evidence to treat patients and avoid infection. In the process, they crafted the disturbing plague doctor costume.

Find out more about the origins of the 17th-century plague doctor’s uniform, shaped by medieval understandings of disease.

A Thankless Job

Among the many horrible occupations of the 17th century, plague doctors ranked near the top. These traveling physicians wandered from place to place. They treated plague epidemics as they arose in various cities and towns across Europe. Without the knowledge of microorganisms or antibiotics, their patient survival rates were dismal. They also faced the constant risk of infection and death.

Besides looking in on the dying, plague doctors sometimes took part in autopsies. They also testified and witnessed wills and other essential documents for plague victims. In other words, their duties were more actuarial than medical. They spent far more time counting bodies and fortunes than curing the sick. They recorded plague casualty figures in their logbooks.

Sure, plague doctors were more respected than other “dirty job” holders like leech collectors, gong farmers, and sin-eaters. Nonetheless, they lived in permanent quarantine, social outcasts only called upon when families were in desperate need. And these physicians died in droves despite the theatrical trappings of their occupational costume.

Generations of Plague

By the 17th century, the plague doctor’s costume represented a potent symbol of the Black Death, a cataclysmic pandemic that raged across Asia, the Middle East, and Europe from 1346 to 1353. This pandemic resulted in the deaths of 30 to 60 percent of Europe’s population. It didn’t end there, though. Each generation saw its return until the end of the 19th century. Despite the costume’s association with the Great Plague, however, it came on the scene much later. Attributed to French physician Charles de l’Orme (1584-1678), he lived nearly 300 years after the initial 14th-century catastrophe.

De l’Orme catered to the needs of many European royals. His patients included Gaston d’Orléans (son of Marie de Medici) and King Louis XIII. As a result, he was in the unenviable position of attending to aristocratic plague victims. Unable to refuse these affluent patients, he carefully crafted a uniform to act as a shield against the deadly disease.

A Terrifying Outfit

The costume included an outer canvas garment covered in suet or scented wax. Beneath this, doctors wore a shirt tucked into leather pants. The leather pants were attached to leather boots. They also wore gloves and a hat.

Over their heads, plague doctors wore a mask and dark leather hood held in place with leather bands and gathered at the neck to keep “bad air” out. Eye holes were cut into the leather and fitted with glass domes. A grotesque curved bird-like beak protruded from the hood, covering the doctor’s face. Last but not least, plague doctors carried wooden sticks. They used these sticks to examine infected patients, avoiding close proximity and skin-to-skin contact. These sticks were also sometimes used by doctors to defend against desperate patients.

The resulting outfit looked like something out of a horror movie or Heavy Metal music video. But de l’Orme designed it with real medical intent. Maybe he and his fellow physicians knew nothing about bacteria, but one thing remained obvious. The disease spread at a frightening pace.

Protecting Against Miasma

To account for the rapid and pervasive spread, doctors believed miasma, noxious “bad air,” was the culprit. To protect against this poisonous air, plague doctors filled the beaks of their costumes with theriac. This concoction of more than 55 herbs included cinnamon, myrrh, viper flesh powder, and honey. Some French plague doctors even set the herbs on fire, producing a protective smoke within the beak. They hoped this smoke would repel ill-humors transmitted in the air.

An early textual description from the Encyclopedia of Infection Diseases: Modern Methodologies explains:

The nose [is] half a foot long, shaped like a beak, filled with perfume with only two holes, one on each side near the nostrils, but that can suffice to breathe and carry along with the air one breathes the impression of the [herbs] enclosed further along in the beak.

Although de l’Orme lived to the ripe old age of 96, his costume did little to quell the plague. As for the level of protection it provided so-called “beak doctors”? That remains up for debate. But he did create a highly recognizable costume that has become an iconic part of European culture still seen regularly in Italian commedia dell’arte theater productions and at Carnival in Venice.

By Engrid Barnett, contributor for Ripleys.com

Source: Why Did 17th Century Plague Doctors Dress Like Birds?

Fries With A Side Of Fries

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

This Week

[April 26th-May 3rd, 2020] Doubling our potato intake, swimming dinosaurs, a Tupac mix up, and the rest of the week’s weird news from Ripley’s Believe It or Not!

Would You Like Fries With Your Fries?

If you’re looking for a small golden lining to your local restaurant or bar being closed until further notice, we may have just the pick-me-up you need. Belgium’s Potato Association is now encouraging consumers to double the amount of potatoes they eat each week! Because of the shutdown of restaurants, Belgium is currently holding a surplus of over 750,000 tons of potatoes! Instead of eating a small side of fries each week, an association of these potato producers is encouraging Belgians to double their intake to help make a dent in the surpluss. Finally—a judgment-free zone when it comes to asking for extra fries!

The Michael Phelpasaurus

Okay, so that’s not the name they went with. But, scientists have just discovered a new fossil in Morocco that reveals a fearsome, toothy creature known as the aegyptiacus—the first known dinosaur to have lived in water! This newly-found tail remain is the first hard evidence that dinos were also kings of the sea! Nearly the same size as the more-popular Tyrannosaurus rex, there’s still much to learn about this carnivorous creature.

TwoPacs Are Better Than One

It seems the name of Tupac Shakur has been labeled as one of the “bad apples” in this global pandemic. During a news conference on Monday, Kentucky Governor, Andy Beshear, labeled Tupac as one of the prank claimers using a fake name to file for unemployment. But, little did he know, this claim was not made for the 90s rap legend. It was filed by a true Lexington resident also named Tupac Shakur. Beshear has since extended his apologies to the [very much alive] restaurant employee.

Beers, Brews, and Antibacterials!

10th Street Distillery is home to single malt whiskeys, spirits, brews, and now, hand sanitizers! Since this San Jose shop temporarily closed its doors as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, they’ve been looking for ways to better evolve their business to meet the needs of their consumers. What better way to help out the community than by turning whiskey into freshly brewed hand-sanitizer?!

Give This Guy A Hand

Every good performance ends with a roaring round of applause. But what if your performance is a round of applause? YouTuber, Jack Peagam of London, decided to challenge himself to a round of applause that would last a full 24 hours. As a child, the Neonatal Unit at St George’s saved Peagam’s life when he was born prematurely at just 32 weeks. Inspired by the weekly Clap for our Carers initiative, he set out to raise £5,000 for the NHS. Surpassing his set goal, Peagam was able to collect £8,075 ($10,168 USD) for a cause very near and dear to his heart.

Source: Fries With A Side Of Fries

CARTOON 05-01-2020

April 30, 2020

Did Charles Lindbergh Make the First Transatlantic Trip in an Airplane?

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

On May 21, 1927, Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974) touched down at Le Bourget Field in Paris, completing the first solo, nonstop transatlantic flight. Just 33 and a half hours before, his single-engine monoplane, the Spirit of St Louis, had taken off from Roosevelt Field, traveling an ambitious 3,600-miles (5,800-kilometers).

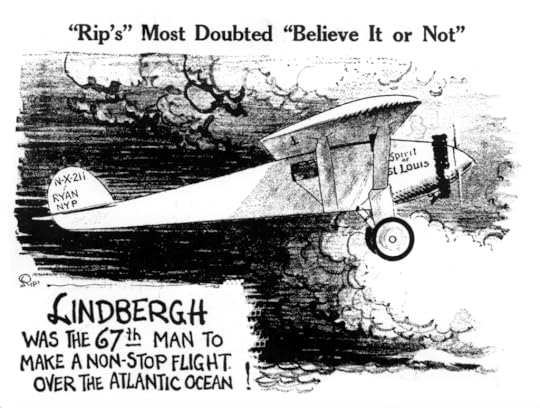

Touted as the most astounding achievement of its day, Robert Ripley featured Lindbergh in Believe It or Not!, his popular syndicated New York Evening Post cartoon, a few months later. Instead of celebrating the flier, however, Ripley pointed out that Lindbergh, far from being the first person to make the crossing, was the 67th!

Ripley soon faced a public outcry, receiving angry telegrams and letters from irate readers who called him a liar. Yet, Ripley knew his facts. Keep reading to learn more about the real first transatlantic crossing by Captain Alcock and Lieutenant Brown as well as the subsequent trips that preceded Lindbergh.

A Groundbreaking Aviation Duo

Today, few people remember the groundbreaking flight of Captain John Alcock (1892-1919) of England and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten Brown (1886-1948) of Scotland in 1919. Yet, these men achieved a milestone in aviation that some experts list on a par with the 1969 moon landing.

Both men honed their flying skills during World War I. Alcock became a prisoner of war after his aircraft’s engine failed over the Gulf of Xeros in Turkey. Brown got shot down and captured over Germany. Yet, despite these war-related aviation traumas, they enthusiastically took on the challenge of completing the first nonstop transatlantic flight.

Alcock and Brown carrying mail on the flight, making it the first transatlantic airmail flight.

The London newspaper the Daily Mail had initially offered a £10,000 prize (more than $1.1 million today) to the “aviator who shall cross the Atlantic in an aeroplane in flight” back in 1913. But World War I intervened in 1914, suspending the competition until 1918.

The Race to the First Nonstop Transatlantic Flight

This delay worked out for the best. It took WWI to develop the type of equipment necessary for such a crossing. What’s more, the timeframe suited Alcock and Brown. Both found themselves unemployed and ready for something new at the end of the Great War. Of course, the competition meant that they were also in a race against time.

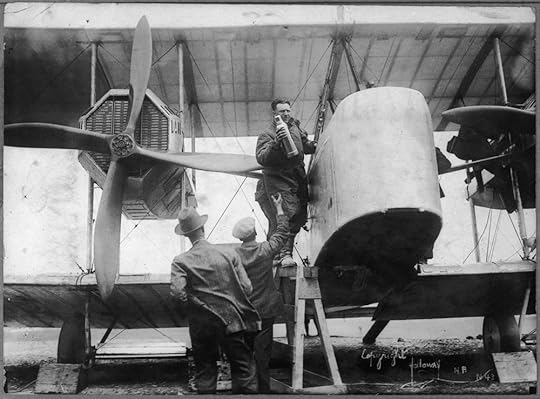

On June 14th, 1919, at 1:45 pm, they began their bold journey across the ocean in a modified Vickers Vimy twin-engine biplane. They departed St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada, where several other teams were also preparing to take up the challenge. While the rest assembled their planes and ran tests, Alcock and Brown hastily set out, barely clearing the trees standing near the end of the runway. To bring them luck, each man carried a toy cat mascot. Alcock called his “Lucky Jim,” and Brown named his “Twinkletoes.”

1919: The First Transatlantic Flight

During a 16-hour-long flight fraught with nearly unnavigable weather, failing equipment, and countless mishaps, the British duo flew nonstop to Ireland. The flight itself proved a disaster from start to finish.

Following the treacherous and bumpy takeoff from St. John’s, their radio failed. Fog soon inundated the pilots. At this early stage in aviation, the men relied on a sextant, an instrument that measured celestial objects in relation to the horizon, for navigation.

Captain John Alcock stowing provisions aboard Vickers Vimy aircraft before trans-Atlantic flight 14 Jun 1919.

But clouds and fog obscured their view of the stars and moon for hours at a time, rendering the sextant useless. To overcome this hurdle, they climbed above the cloud cover to get a good glimpse of the sky, yet this solution brought new obstacles.

Just When It Couldn’t Get Worse

Higher elevations meant freezing temperatures, which covered the plane in ice and snow. The men had to frequently stand up and clear the white stuff from the plane’s instrument sensors outside the cockpit. At one point, ice covered the air intake of one engine, spelling disaster. Alcock had to turn it off so that it wouldn’t backfire and cause damage.

They survived on coffee, whiskey, and sandwiches and passed the time by singing. They also conversed anxiously about the weather and if it would damage their fuel tanks.

At one point, they faced a near-fatal stall. The overloaded aircraft’s exhaust pipe blew, making communication above the roar impossible. Then, the plane’s wind-driven generator failed, leaving the two without heat. Alcock and Brown froze in their open cockpit. Just when it seemed nothing else could go wrong, they descended to 500 feet in an attempt to give the aircraft a chance to thaw. The engine restarted, they broke into clear skies, and a patch of emerald land lay before them.

A Historic Landing

On June 15th, 1919, at 8:40 am, their aircraft touched down in an Irish bog near Clifden, County Galway. They had mistaken a relatively flat swathe of green for marshland and severely damaged their plane in the aftermath. While the landing proved unceremonious, Alcock and Brown had achieved the impossible.

Vimy arrival in Ireland

Up to this point, the only way to cross the Atlantic was by ship. The crossing took between 116 and 137 hours or 4.8 to 5.7 days. In comparison, a 16-hour flight was an exciting development. A century later, millions of people fly across the Atlantic every year thanks to commercial aviation. Yet, such advancements would have been inconceivable were it not for Alcock and Brown’s historic flight.

National Recognition

To celebrate their monumental achievement, the Secretary of State for Air, Winston Churchill, presented Alcock and Brown with the Daily Mail prize for their nonstop crossing in less than 72 consecutive hours. A week later, the aviation duo received the honor of Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (KBE) by King George V at Windsor Castle.

Unfortunately, their triumph proved short-lived. On December 18th, 1919, Alcock died in a crash over France on his way to the Paris Airshow.

His sudden and tragic end proved a reminder of just how dangerous aviation was in its infancy. Brown survived to the ripe old age of 62, a miracle considering his daredevil lifestyle. He died on October 4th, 1948.

History’s Poor Memory

Many people mistakenly associate Charles Lindbergh with the first nonstop transatlantic crossing by plane, but Alcock and Brown hold the record. Lindbergh did, however, make the first solo crossing. But what about the 64 other people that Ripley claimed came before Lindbergh?

In 1919, following Alcock and Brown’s successful transatlantic crossing, a dirigible carrying 31 men crossed from Scotland to the United States. Then, five years later, a second dirigible traveled from Germany to Lakehurst, New Jersey, with 33 passengers on board. The official tally comes to 66 individuals who made the nonstop trip before Lindbergh.

The Customer Is Never Right

It was this type of shocking, yet truthful, storytelling that endeared audiences to Ripley in the first place. From stories of a chicken who lived 17 days after its head was cut off to tales of a German strong woman who juggled cannonballs, Ripley’s cartoons always proved true. No matter how improbable they appeared on the page.

By 1936, fans had forgotten their outrage about Lindbergh, and Ripley was one of the most famous men in the United States. He ranked as more popular than President Roosevelt, Jack Dempsey, James Cagney, and even Charles Lindbergh. As Ripley sagely noted, “I think mine is the only business in which the customer is never right.”

By Engrid Barnett, contributor for Ripleys.com

EXPLORE THE ODD IN PERSON!

Discover hundreds of strange and unusual artifacts and get hands-on with unbelievable interactives when you visit a Ripley’s Odditorium!

Source: Did Charles Lindbergh Make the First Transatlantic Trip in an Airplane?

CARTOON 04-30-2020

April 29, 2020

The Circus Is On Call: Request A Circ-A-Gram

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

Smiling faces, visits from friends and family, light-hearted entertainment—all are essential in keeping people, especially children, comforted and calm. Amidst COVID-19, social distancing has restricted these interactions, and places like hospitals—that need the smiles the most—have limited these uplifting measures. Emergency Circus has come to the rescue with Circ-a-Grams.

Based in New Orleans, Louisiana, Emergency Circus founder Clay Mazing has taken to the streets to deliver Circ-a-Grams around the Big Easy. Atop his “Shzambulance,” Clay dazzles audiences from afar with knife juggling, bullwhip stunts, and the message that we all have “superpowers” like his well-trained circus skills—they’re just waiting to be unlocked through dedication and confidence.

New Orleans is not just Clay Mazing’s home base, but also a pandemic epicenter—another reason why he is offering his support locally.

“[It’s an] inspirational show about believing in yourself and your abilities to become a superhuman,” said Clay Mazing. “Circ-A-Grams [are] for kids and adults who need a little extra excitement to blast away the mental health issues that come with boredom and uncertainty.”

The mental health impacts of COVID-19 are not to be overlooked. Physical, financial, occupational, and social stresses are taking a toll on people globally. This is even evident in new sleep patterns, as “can’t sleep” has been trending since stay at home orders have been mandated.

“Juggling knives in a superhero outfit on top of a Shzambulance is the only thing keeping me sane these days,” said Clay Mazing—a relatable sentiment as we all go a little stir crazy.

Need some sanity—or circus insanity—yourself? Simply call 1-(NOW)-CIRCUS-1 and leave a message to request a performance. Let Clay Mazing know if you are local to New Orleans or if you require a virtual visit. Circ-a-Grams are free, as many in need can’t always afford entertainment, but donations via PayPal help support these 15-minute circus spectacles.

With the motto “bringing joy to the under-circused,” the Emergency Circus was established in 2012. This selfless troupe has spread circus joy all over the world, from Syrian refugee camps in Jordan to hurricane disaster zones in Puerto Rico. Pre COVID-19, Emergency Circus expected to be in Iraq this month.

This non-profit brings laughs and love where health and happiness struggle. Through performance and the power of the human spirit, a Circ-a-Gram can replace your stresses with smiles during this unprecedented time.

In the wise words of Clay Mazing, “Sometimes to break the spell of monotony all you need is a guy with a megaphone in blue striped tights juggling knives to Bonnie Tyler’s “holding out for a hero” on top of a circus tent painted ambulance.”

Call 1-(NOW)-CIRCUS-1 to request a performance or donate to the cause on PayPal, made possible through the Emergency Circus website.

CARTOON 04-29-2020

April 28, 2020

Blood In The Water: The Real-Life Shark Attacks That Inspired Jaws

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

During the summer of 1916, a series of violent deaths shattered the peace of New Jersey’s coastal areas. For 14 days in July, people entered the water at their own risk as five swimmers found out firsthand. Rumors of shark attacks soon circulated.

Nonetheless, the public proved skeptical. Early 20th-century wisdom held that sharks were harmless, and humans ranked at the top of the food chain. Once a finned culprit with human remains in its stomach turned up, though, people started to reformulate their opinions.

Today, movies like Jaws, The Shallows, In the Deep, and Sharknado show just how far our perspectives have shifted when it comes to the ocean’s apex predator. Let’s take a look at where America’s shark fears and fascination originated, sunny Beach Haven.

Sliding Back Down the Food Chain

Located 16 miles (by water) from Atlantic City, the ocean near Beach Haven teemed with swimmers and sunbathers loaded the beach on July 1st, 1916. Suddenly, a bloodcurdling scream pierced the paradisiacal atmosphere.

Local lifeguard, Alexander Ott, and Sheridan Taylor, a bystander, rushed into the water, pulling 25-year-old Penn State graduate, Charles Vansant, from the sea. A shark pursued them back to shore. Vansant bled to death on the manager’s desk at the Engleside Hotel. Yet, scientists initially saw no cause for alarm. They declared his death a freak accident, unlikely to happen again.

Until it did…

Just five days later and 45 miles to the north, the creature struck again near the Essex & Sussex Hotel located in Spring Lake. Swimming about 100 yards from shore, Charles Bruder, a Swiss bell captain, began thrashing in the water. Onlookers thought Bruder struggled with a capsized, red-bottomed boat. Yet, when lifeguards paddled their craft out to assist him, they made a shocking discovery. The red in the water was blood.

Grabbing onto Bruder, they pulled his legless torso into the boat. Bruder’s last words sounded incredulous, “A shark bit me! Bit my legs off!” He died of blood loss before reaching land.

Some now began to articulate the unimaginable. A shark was hunting beach-goers off the Jersey Shore.

Resorts installed mesh barriers in the water near popular beaches, but it was too late to salvage tourist season. Panic took hold. Nobody wanted to get back in the water. Then, the unthinkable happened.

Terror at the Creek

In the small town of Matawan, 30 miles north of Spring Lake, residents read about the two shark attacks in the local paper. They felt reassured by their 16-mile distance from the shore. Instead of ocean swimming, most residents preferred the local creek, a narrow tidal waterway sheltered from open water. Although the creek eventually wound its way to the Atlantic, the distance put people at ease. Swimmers regularly filled its waters.

The idea of a shark attack sounded preposterous to everyone, including retired sea captain Thomas Cottrell. Cottrell changed his mind, however, on July 12th. While crossing a trolley bridge over the Matawan Creek, he spotted the silhouette of a massive shark making its way inland. He ran into town, immediately notifying the police. Yet, they chalked up his observations to heatstroke. That afternoon, Cottrell’s suspicions were confirmed.

At approximately 2:00 pm, 11-year-old Lester Stillwell splashed in the Matawan Creek with his friends near the Wyckoff dock. Suddenly, something pulled Lester beneath the water. Screams filled the air as his head bobbed up and down on the surface. To the horror of his friends, the water turned scarlet.

Another Attack

The boys emerged from the creek in a panic, sprinting into town. Covered in mud and terror, they ran through the streets, screaming for help. A group of townspeople assembled, heading for the creek. Since Lester had epilepsy, they assumed he suffered a seizure.

Among the group was Watson Stanley Fisher, a 24-year-old businessman. He dove into the water, searching for the boy but found a shark instead. The beast clamped onto Fisher’s leg, ripping half the flesh from his thigh. Although he managed to escape and swim ashore, he succumbed to his injuries at Monmouth Hospital in Long Branch that evening.

The Philadelphia Inquirer reported the capture of a “man-eating” shark off the Jersey Shore after the attacks.

The reign of terror by New Jersey’s “Jaws” was not over, though. Less than one mile from Fisher’s attack, and about 30 minutes later, the shark found a new victim. The toothy predator clamped into the leg of 14-year-old Joseph Dunn. Joseph was at the creek with Michael, his brother, and a handful of friends.

Just 10 feet from the shore, Michael and another boy, Jacob Lefferts, grabbed hold of Joseph, locked in a tug-of-war with the monster. Luckily, the boys won. Although shark teeth had sheered much of the flesh from Joseph’s leg, his bones and major arteries remained intact. He required amputation, becoming the lone survivor of the shark’s killing spree.

Catching the Matawan Man-Eater

Despite the mounting evidence, many Americans refused to believe that a shark was capable of such attacks. After examining Charles Bruder’s body, John Treadwell Nichols of the American Museum of Natural History ruled the cause of death attack by a killer whale. Others suggested a massive sea turtle (or school of sea turtles) killed Vansant and Bruder. Scientists had a poor grasp of marine wildlife, let alone shark behavior, at the time. Ocean swimming also remained a new recreational activity in 1916, which meant few encounters between sharks and people had been recorded.

Views began to shift, however, when Michael Schleisser, Harlem taxidermist and Barnum and Bailey lion tamer, hauled in a 7.5-foot-long, 325-pound shark near the mouth of the Matawan Creek on July 14th. The shark attacked and nearly sank Schleisser’s boat before he managed to kill it with the only weapon at his disposal, a broken oar.

Michael Schleisser and a great white shark captured in Raritan Bay, suspected to be the culprit of the Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916.

Scientists who examined the body declared it a great white shark. They also found approximately 15 pounds of human bones and flesh in the predator’s stomach. The Matawan Man-Eater had been caught.

Blaming the Germans

Although the identity of the creature behind the attacks could no longer be denied, hypotheses still circulated about what inspired a shark to prey on people in the first place. Some even blamed the taste for human flesh on World War I and the maneuvers of German U-boats near America’s east coast.

A letter to The New Times dated July 15, 2016, argued, “These sharks may have devoured human bodies in the waters of the German war zone and followed liners to this coast, or even followed the Deutschland herself, expecting the usual toll of drowning men, women, and children…. This would account for their boldness and their craving for human flesh.”

The Jersey “Jaws”

Today, our views on sharks have evolved dramatically. Yet, what drove the behavior of the Jersey “Jaws” remains a mystery. Having one individual implicated in multiple incidents is very rare. Only a handful of similar examples exist in history, like the 2010 attacks near Sharm el-Sheikh, a Red Sea resort in Egypt.

Some scientists also question the species of the Matawan Man-Eater. Although identified as a great white shark, the monster’s behavior sounds akin to that of a bull shark, a species known for aggressive attacks and affinity for brackish and freshwater. Some scientists also hypothesize that more than one shark may have been involved in the attacks. Nonetheless, George Burgess, director of the Florida Program for Shark Research, has concluded that the evidence to date still supports the narrative of one great white as the perpetrator.

By Engrid Barnett, contributor for Ripleys.com

EXPLORE THE ODD IN PERSON!

Discover hundreds of strange and unusual artifacts and get hands-on with unbelievable interactives when you visit a Ripley’s Odditorium!

Source: Blood In The Water: The Real-Life Shark Attacks That Inspired Jaws

Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s Blog

- Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s profile

- 52 followers