Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s Blog, page 197

June 19, 2020

CARTOON 06-19-2020

June 18, 2020

Americans Invented The Automobile, Right?

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

Like the Great American road trip, the history of the automobile represents a long and winding journey. Attempting to pinpoint the origins of the concept proves tricky. Maybe that’s why so many have gotten confused about this technology’s birthplace.

While countless folks take for granted that American engineers created the first cars, nothing could be further from the truth. And if you think the idea for self-propelled vehicles dates to the 19th century, you’re in for even more surprises.

Get ready for a wild ride that would leave Mr. Toad queasy as we celebrate the anything-but-straight path to the invention of the automobile.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Foray into Self-Propelled Vehicles

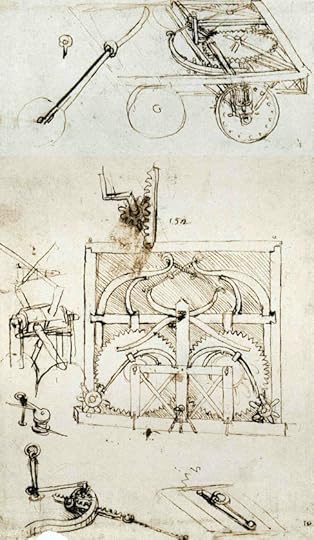

Like so many other inventions that would come to define Western Civilization, Leonardo da Vinci dabbled in the concept for the “automobile” in the early 15th century. He did so in the form of a series of sketches showing a mechanized cart. Again, like most of his designs, the idea remained conceptual.

Da Vinci never attempted to bring the mechanism to life. However, some researchers estimate that the gadget would’ve been capable of moving up to 130 feet (40 meters) before requiring recoiling. They base their speculation on the instructions provided by da Vinci, including the spring diameters.

The original design of the self-propelled cart.

Far from a car in the modern sense of the word, it still proved a well-designed, self-propelled machine. A team from The Institute and Museum of the History of Science in Florence set out to recreate the invention, following da Vinci’s specs to a tee. They spent three months designing the three-dimensional representation, crafting its many components from five different types of wood (as stipulated by the Italian master himself.) In 2004, they finished the model and tested it.

The result? The self-propelling cart’s coils and wooden mechanics did, indeed, move it forward. Even more impressive, da Vinci’s invention included a steering column and a rank and pinion gear system, both essential to steering assemblies today. Although the “car” design had no seats and limited endurance, da Vinci’s horseless carriage remains downright steampunk.

Sailing Chariots and Steam Engine Carts

When it came to prototypes for the automobile, da Vinci proved among the first to hazard a mechanized, self-propelled vehicle. He had predecessors when it came to making horses redundant, however. The Chinese had sailing carriages for transportation as early as the 6th century AD. The Taoist scholar and crown prince, Xiao Yi, described them in the Book of the Golden Hall Master. Yi noted that Gaocang Wushu invented a “wind-driven carriage” that could carry 30 people at a time. In 610 AD, the Emperor Yang of Sui (r. 604-617) commissioned one according to the Continuation of the New Discourses on the Talk of the Times.

Westerners who visited China in the 16th century, like Gonzales de Mendoza, were amazed by these contraptions. They transported the concept back to Europe, where fantastical experiments soon followed. According to Jacques de Gheyn II, Simon Stevin (a.k.a. Stephinus or Stevinus) of Holland constructed a wind yacht. In 1600, he took Prince Maurice of Orange and 26 guests on a trip from Scheveningen to Petten, passing horses along the way.

Yet, the concept of the self-propelled vehicle evaded Europeans for another century and a half. In 1769, Nicholas-Joseph Cugnot of France constructed a self-propelled vehicle using a steam engine. Designed to move artillery pieces on the battlefield, it operated at two mph (3.2 km/h), stopping every 20 minutes to build more steam.

Internal Combustion Engines

Of course, internal combustion engines distinguish automobiles from their sailing chariots and steam-powered cart ancestors. While you might think of them as a recent invention, guess again. Their history dates to the 17th century.

In 1680, Christiaan Huygens, the famed astronomer, designed an internal combustion engine powered by gunpowder. A dangerous proposition, Huygens was likely wise to leave this concept in his sketchbook.

A century and a half later, in 1826, Samuel Brown of England altered a steam engine to burn gasoline. He attached it to a carriage creating the prototype of a car with an internal combustion engine. His concept never gained widespread interest, though.

Refining the Internal Combustion Engine

By 1858, Jean Joseph-Etienne Lenoir patented another combustion engine fueled by coal gas. His double-acting, electric spark-ignition internal combustion engine proved both a mouthful and a smashing success. After altering the engine to run on petroleum and improving its performance, he attached it to a three-wheeled wagon. It traveled 50 miles.

By 1873, an American finally entered the inventing frenzy. George Brayton designed a two-stroke kerosene engine less likely to blow up in your face. Literally. Three years later, Nikolas August Otto patented the four-stroke engine in Germany, and by 1885, Gottlieb Daimler invented the prototype of the gasoline version we know today.

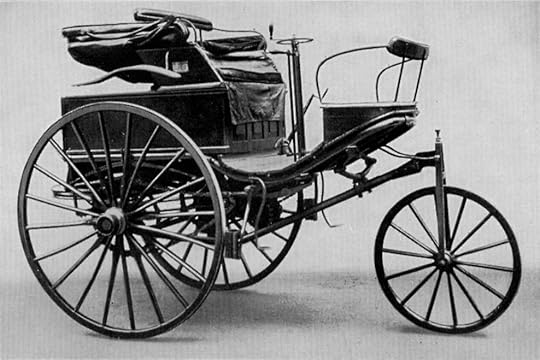

But the man who entered history books as the father of the modern car is none other than Karl Benz of Germany. In 1886, he patented the three-wheeled Motor Car or “Motorwagen.” Fully equipped with everything from spark plugs to a throttle system, gear shifters to a carburetor, Benz’s invention smacks of an honest-to-goodness ride.

The Benz Patent-Motorwagen Number 3 of 1888, used by Bertha Benz for the first long-distance journey by automobile (more than 106 km or sixty miles).

Early Electric Vehicles

A handful of electric vehicles also made their mark on early automotive history. By 1881, the French chemist Camille Faure improved the lead-acid battery design by Plante, rendering it a viable choice for drivers. In 1891, the American designer William Morrison successfully built the first electric vehicle. And in 1899, the Belgian race car driver, Camille Jénatzy, set a new land speed record of 62 mph (100 km/h) in his hand-crafted electric race car.

German automotive engineer Ferdinand Porsche designed the first hybrid vehicle in 1900. Even Thomas Edison got in on the action in 1907, developing a nickel-alkaline battery that proved more durable and less hazardous than lead-acid batteries. His invention never caught on because of its high initial cost, though.

Nonetheless, electric cars continued to gain attention and recognition. The first automobile race on American soil was a 52-mile dash between Chicago and Waukegan, Illinois, held in 1895. Two of the six entrants in the competition drove electric automobiles. By 1900, one-third of all cars on the road were electric, and the New York City taxi service boasted a fleet of 60.

How Automobiles “Became” American and Gas-Powered

In 1908, everything changed, however. That’s when Henry Ford introduced his inexpensive Model T to the American public. The high-quality, gas-powered vehicle quickly gained in popularity. In turn, it signaled the demise of electric and hybrid cars and the advent of America’s car culture. Over time, cars have become so synonymous with the United States, that many have come to assume Americans invented them. In reality, this couldn’t be further from the truth.

A 1924-1925 Ford Model T Roadster in Gedee Car Museum, Coimbatore, India || CC: SnapMeUp

The history of the automobile is surprisingly colorful and circuitous. Stretching back to the 6th century AD in China, people have remained fascinated by the idea of horseless travel. Many great thinkers, from da Vinci to Benz, have contributed along the way. What Americans such as Ford did do, however, is transform them from fun inventions into essential parts of daily life.

By Engrid Barnett, contributor for Ripleys.com

EXPLORE THE ODD IN PERSON!

Discover hundreds of strange and unusual artifacts and get hands-on with unbelievable interactives when you visit a Ripley’s Odditorium!

CARTOON 06-18-2020

June 17, 2020

The Tomb Of Tutankhamen And The “Curse Of The Pharaohs”

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

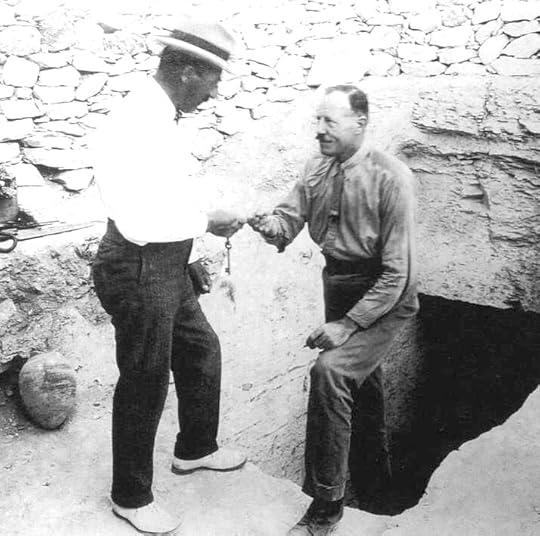

On November 22nd, 1922, Howard Carter and a team of archaeologists uncovered steps hidden in debris near the entrance of a tomb in Thebes, Egypt. The steps led to another tomb’s entrance inscribed with the name Tutankhamen, the famed boy king of Egypt. When Carter and his crew entered its interior chambers four days later, more than 3,000 years of repose came to a sudden halt.

Some believe a vicious curse of death and destruction got unleashed with the tomb’s unsealing. Did the young pharaoh’s final resting place really contain a vindictive spell meant to deter grave robbers? Here’s what we know about the most famous curse in Egyptology, and the lives it’s thought to have cut short.

The Curse of Egypt’s Kings

“Curse be those that disturb the rest of Pharaoh. They that shall break the seal of this tomb shall meet death by a disease which no doctor can diagnose.” (Inscription attributed to an Egyptian royal tomb)

The opening of King Tutankhamen’s tomb on November 26th caused a media sensation.

Unlike other burial chambers excavated in Egypt, Tutankhamen’s final resting place remained intact despite several apparent grave robberies. Carter and his British financier, Lord Carnarvon, reveled in the exploration of the treasure-filled rooms. The men, along with their crew, painstakingly documented the grave goods within each of the tomb’s chambers.

Lord Carnavon on the steps to the tomb Tutankhamun and Howard Carter (left)

On February 16th, 1923, Carter opened the door to the last chamber. Inside, archaeologists found a sarcophagus with three coffins nested inside it. The innermost coffin was made of solid gold and contained Tut’s mummified body. The tomb also revealed priceless artifacts, from jewelry to statues, golden shrines to a chariot, weapons, and clothing. The most valuable object of all? The fully intact mummy itself.

The Western Fascination with Ancient Egypt

Although fascination with Egyptian culture first captured the Western European imagination in the 17th and 18th centuries, it gained serious traction in the 19th century. That’s when Jean-François Champollion first used the Rosetta Stone to decipher ancient hieroglyphics. Champollion’s contributions to Egyptology permitted the world a taste of the vast wealth of knowledge contained in ancient Egyptian texts. It also inspired the imaginations of authors.

By 1869, Louisa May Alcott’s short story “Lost in a Pyramid; or, The Mummy’s Curse” (1869) made the first mention of a full-fledged curse. By the late 19th-century, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes mysteries, established Egypt as a source of maleficence with stories like “Lot No. 249” and “The Ring of Thoth.”

As Dipsikha Thakur notes, “[Doyle] was one of the Victorian occultist voices that gave rise to the curse of the mummy—today a well-known Orientalizing trope in film and fiction.” Now, you’d be hard-pressed to find a popular work of fiction or film dealing with mummies that doesn’t rely on the curse plot device to some degree.

A Worldwide Sensation

Of course, Carter’s team remained undeterred by such fictional representations, working meticulously to catalog and describe the trove they uncovered. These treasures would end up a part of the iconic traveling exhibition called the “Treasures of Tutankhamen.” Today, the exhibition is permanently housed at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Nevertheless, the discovery of Tut’s tomb created a worldwide press sensation fueled by sinister hints of an ancient curse. The New York World and the Times London published a warning from best-selling novelist, Marie Corelli, “The most dire punishment follows any rash intruder into a sealed tomb.” Some claim Carter even promoted the curse to keep looters away from the site. When people associated with the discovery started dying violently, however, the media coverage became frenzied.

Photo from The Times – The New York Times photo archive, via their online store

The first strange event occurred on the day of the tomb’s opening. Carter returned home to find his canary’s head in the mouth of a cobra. A potent symbol of the Egyptian monarchy, the cobra metaphor was not lost on Carter. Several months later, Lord Carnarvon died at the age of 56 in Cairo from an infection related to a mosquito bite. Following his death, a citywide blackout overtook Cairo. Wild journalistic speculation followed, and papers flew off newsstands.

Speculation Followed by Death

British journalist, Arthur Weigall, claimed to have predicted Carnarvon’s death months prior, saying Carter’s benefactor had laughed and acted disrespectfully at the tomb. Weigall recalled that he’d given the Lord “six weeks to live.” Sir Arthur Conan Doyle got in on the action, too. He speculated to American journalists that “an evil elemental” spirit conjured by ancient Egyptian priests had killed Lord Carnarvon.

The sensational journalism surrounding Tutankhamen’s tomb and the “curse of the pharaohs” contributed to a widespread belief that all Egyptian tombs contained curses. Today, we know this is far from true, though. While they do exist, examples of ancient Egyptian tomb curses prove rare. The few that survive are almost legalistic in structure. They proscribe specific punishments for various transgressions. Like most Egyptian tombs, Tut’s contained no mention of curses.

The Unwritten Curse Claims More Victims

Despite the lack of a written curse, death appeared to stalk Carter and his former team members. Or, at least that’s what journalists wanted the public to believe. A little imagination and a lot of sensational journalism soon convinced the world that the “curse of the pharaohs was real.” Evil supernatural powers appeared to be at work from beyond the grave.

Victims included Prince Ali Kamel Fahmy Bey of Egypt, shot dead by his wife in 1923. Members of the original excavation team soon followed. In 1924, Sir Lee Stack was murdered. In 1928, Arthur Mace died of arsenic poisoning. Richard Bethell suffocated to death in 1929, and his father committed suicide in 1930. When Howard Carter died of Hodgkin’s Disease in 1939, the story sparked to life once more.

A Beneficial Curse?

While some asserted that the string of deaths associated with Tutankhamen’s tomb proved the “curse of the pharaohs” was real, others attributed it to bad luck. Investigator James Randi decided to dig deeper. After exploring the “casualties” associated with Tut’s tomb, he came to some fascinating conclusions.

The average life expectancy after exposure to the “curse” was 23 years. Some people associated with the excavation lived much longer. Carnarvon’s daughter, who was involved in the discovery, died in 1980. Richard Adamson, who guarded the tomb for seven consecutive years, lived until 1982. Randi’s research showed that members of the “cursed” Tut group died at an average age of 73 years old, slightly longer than the life expectancy for individuals of their social class and time period. If anything, Tut’s curse proved beneficial.

Other events related to the curse, such as the canary killed by the cobra, have also been debunked. Many now believe an Egyptian released the snake in Carter’s home to deter him from exploring the tomb. As for Carnarvon’s death? Some scientists suggest he succumbed to molds and pathogenic bacteria buried along with Tut. It remains more likely, however, that he died from the infected mosquito bite. One thing’s for sure, though. The curse helped sell plenty of newspapers!

By Engrid Barnett, contributor for Ripleys.com

EXPLORE THE ODD IN PERSON!

Discover hundreds of strange and unusual artifacts and get hands-on with unbelievable interactives when you visit a Ripley’s Odditorium!

Source: The Tomb Of Tutankhamen And The “Curse Of The Pharaohs”

CARTOON 06-17-2020

June 16, 2020

CARTOON 06-16-2020

June 15, 2020

CARTOON 06-15-2020

June 14, 2020

CARTOON 06-14-2020

June 13, 2020

CARTOON 06-13-2020

June 12, 2020

The Plague Cure-All: Toad Vomit Lozenges

Featured in Ripley's Believe It or Not!

This Week

[June 8-June 14, 2020] An astronaut reaching new depths, toad vomit treatments, the Dalai Lama’s latest album drop, and the rest of the week’s weird news from Ripley’s Believe It or Not!

From The Stars To The Sea

Thirty-six years after her debut as the first American woman to walk in space, Kathy Sullivan has made history once again. On Monday, June 9th, Sullivan became the first woman to travel to the deepest part of the ocean floor. She descended 35,810 feet (about 7 miles) to Challenger Deep—the lowest part of the Marianas Trench. “As a hybrid oceanographer and astronaut, this was an extraordinary day, a once in a lifetime day…” Sullivan said.

Astronaut Kathryn Sullivan using binoculars to view the earth during STS-41-G in 1984.

A Pandamonium At The Copenhagen Zoo

Xing Er, a giant panda at the Copenhagen Zoo, seemed to have had enough of our stay-at-home orders. The 7-year-old male panda broke out of the newly-built, $24 million pen that he shares with a female giant panda, Mao Sun. According to the zoo, Xing Er climbed up a pole covered in wires, into a garden, and out of the enclosure. Thankfully, his breakout occurred before the zoo’s normal operating hours. He was returned to his pen unharmed.

The Dalai Lama: Spiritual Leader and Chart Topper?

If you’re looking for a new quarantine vibe or inspirational playlist, look no further than the teachings of the Dalai Lama. On the spiritual leader’s 85th birthday, July 6, 2020, his album called Inner World will drop. The anticipated release will include a unique mix of mantras and teachings by the Dalai Lama himself. Set to music, each teaching “cultivates an understanding of love and empathy for ourselves and all beings,” says the Dalai Lama’s official website.

A Recipe For Toad Vomit Lozenges

Aside from the three laws of motion, Sir Isaac Newton was, apparently, dabbling in plague treatment research during his time. An unconventional idea, to say the least, Newton expressed his theory in treating the black death using toad-vomit lozenges. Detailed instructions were written on how to create this toad-vomit treatment: a process that involves suspending a dead toad by its hind legs in a chimney, collecting its vomit, and mixing the powdered remains of the toad with its hurled contents. And in Newton’s opinion, this recipe for success was truly the best around.

The Hunt Is Over

After more than 10 years of searching, one lucky treasure hunter has finally uncovered Forrest Fenn’s chest of jewels and riches buried out in the Rocky Mountains. Fenn published a memoir after burying this $1 million treasure, which included a poem of clues to where the chest was buried. The writings soon became a bestseller, and people all over the world came to the area to search for the fortune. Some doubted its existence, and at least five people gave their lives searching for it.

After all these years, the lucky hunter contacted Fenn with a photo of his newfound riches as proof, and he was able to confirm the location and the discovery. Fenn also said that the discoverer—a man from “back East”—wishes to remain anonymous.

Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s Blog

- Ripley Entertainment Inc.'s profile

- 52 followers