Robert MacLean's Blog, page 2

August 23, 2015

In Praise of Older Women

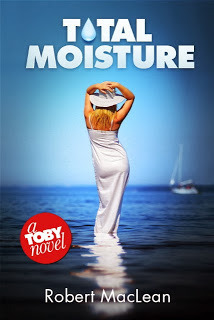

The "Toby" books:Foreign Matter at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT, Amazon ES and Smashwords; Total Moisture at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT, Amazon ES and Smashwords; The Cad at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT, Amazon ES and Smashwords;Will You Please Fuck Off? at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT, Amazon ES and Smashwords;and the un-Toby books,

Mortal Coil: A Comedy of Corpses at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT and Amazon ES;The President's Palm Reader: A Washington Comedy at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT and Amazon ES; and

Greek Island Murder at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT and Amazon ES.

Published on August 23, 2015 05:45

November 21, 2013

Gorgeousness

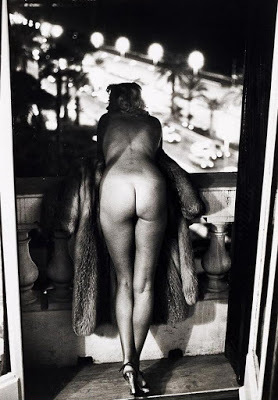

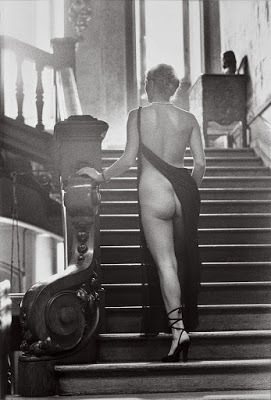

I don't want a state of grace; I want a state of gorgeousness!In an age when beauty is out of style, the work ethic dominates the Internet and there hasn't been a painting or a poem for decades, let us reflect a little on gorgeousness.

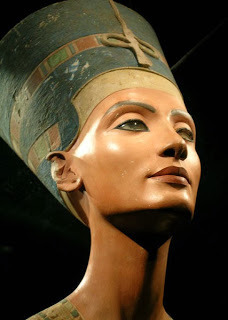

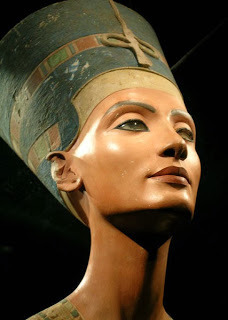

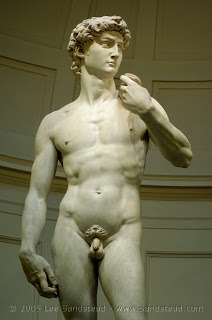

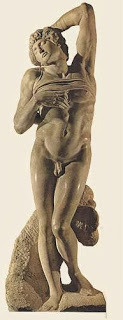

Seven Sculptures The word is from the French for throat, so let Nefertiti be its patroness. This likeness is from five hundred years before Homer—who says the Greeks invented sculpture? Beautiful women, fully alive, have declined to be in the same room with her, so as not to suffer comparison.

The word is from the French for throat, so let Nefertiti be its patroness. This likeness is from five hundred years before Homer—who says the Greeks invented sculpture? Beautiful women, fully alive, have declined to be in the same room with her, so as not to suffer comparison.

Seven SeasHomer, Scheherazade, Dante, Boccaccio, Rabelais, Montaigne, Shakespeare.

Seven FilmsTrouble in Paradise, To Be or Not to Be (the Lubitsch version), Ninotchka, La Dolce Vita, 8 ½, Satiricon, Party (de Oliveira's).

Seven Novels

Satyricon, Crime and Punishment, In Search of Lost Time, Ulysses, The Great Gatsby ("there was something gorgeous about him"), Under the Volcano, Lolita.

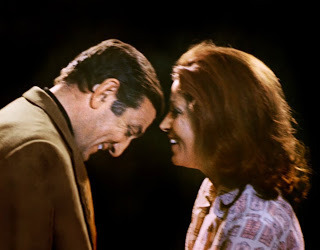

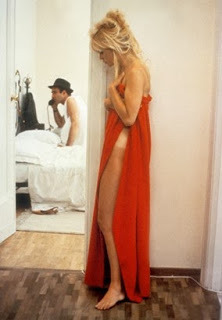

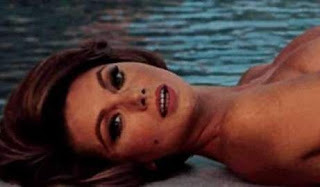

Seven BeautiesSophia; Audrey; Brigitte; Ann-Margret; Sylva; OK, Marilyn; and yes, Joan:

All of them are from the P7 sixties—the post-penicillin, pregnancy-prevention-pill, post-puberty sixties, when sex was just being invented. Polymorphous perverse sex, I mean, and these women embodied it. In The Seven Year Itch Marilyn handles a heat wave by keeping her panties in the ice box.

All of them are from the P7 sixties—the post-penicillin, pregnancy-prevention-pill, post-puberty sixties, when sex was just being invented. Polymorphous perverse sex, I mean, and these women embodied it. In The Seven Year Itch Marilyn handles a heat wave by keeping her panties in the ice box.

Then came the aphrodisiac drugs (Blake predicted "an improvement of sensual enjoyment" around that time)—and scarcely a decade later, the new diseases. Now we don't have sex any more, not with other people, especially when we're married ("If you are afraid of loneliness," said Chekhov, "do not marry"), and have taught ourselves new desires, new ambitions, rather grotesque ones in my opinion. O Hamlet, what a falling-off was there!

Then came the aphrodisiac drugs (Blake predicted "an improvement of sensual enjoyment" around that time)—and scarcely a decade later, the new diseases. Now we don't have sex any more, not with other people, especially when we're married ("If you are afraid of loneliness," said Chekhov, "do not marry"), and have taught ourselves new desires, new ambitions, rather grotesque ones in my opinion. O Hamlet, what a falling-off was there!

Seven Ungorgeous ThingsMusic by Shostakovich; paintings by Jackson Pollock; German food (except for bratwurst); British food (except for fish 'n' chips); prose by Stephen King, Bret Easton Ellis and Jay McInerney (I think they're all the same guy); California wine, unless nothing else is available—unless zero is available; milk.

Seven Ungorgeous ThingsMusic by Shostakovich; paintings by Jackson Pollock; German food (except for bratwurst); British food (except for fish 'n' chips); prose by Stephen King, Bret Easton Ellis and Jay McInerney (I think they're all the same guy); California wine, unless nothing else is available—unless zero is available; milk.

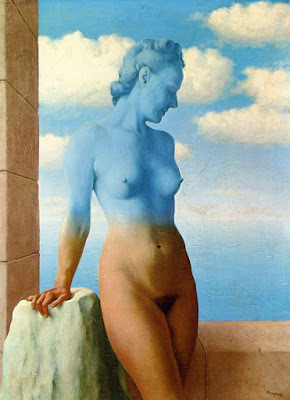

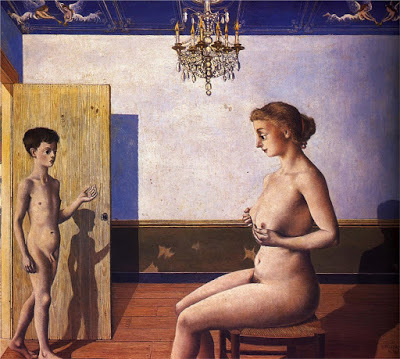

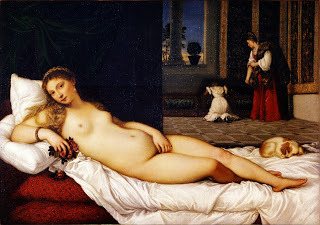

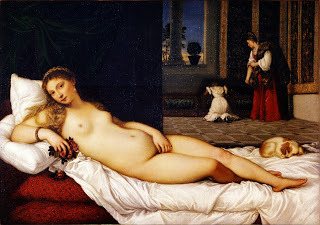

Seven Paintings Catholicism and Hinduism are gorgeous. Judaism, Islam, Protestantism—well. It seems you have to be polytheistic to be gorgeous. Being Catholic is a matter of infinite complications; being Protestant, of stark simplicities. The problem the Germans (pity them!) are having with the Greeks right now is one of infinite complications.

Catholicism and Hinduism are gorgeous. Judaism, Islam, Protestantism—well. It seems you have to be polytheistic to be gorgeous. Being Catholic is a matter of infinite complications; being Protestant, of stark simplicities. The problem the Germans (pity them!) are having with the Greeks right now is one of infinite complications.

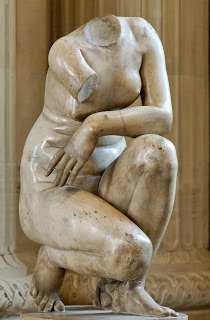

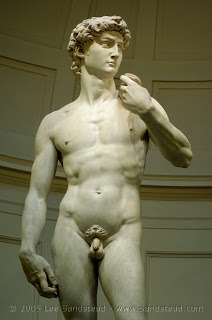

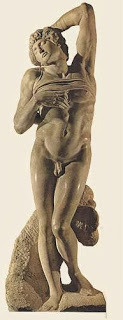

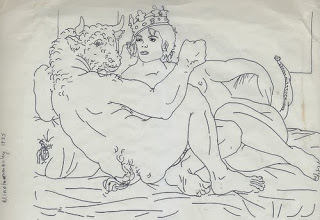

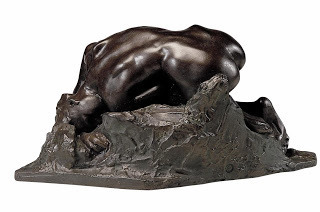

We've been surrounded by puritan imagery for two hundred years, Wordsworth's God brooding in solitude over the abyss. Homer's gods "dwell in bliss," and though that sterilizer Plato hates the idea, heaven may well be an orgy. Look at the company Michelangelo's God keeps:

We've been surrounded by puritan imagery for two hundred years, Wordsworth's God brooding in solitude over the abyss. Homer's gods "dwell in bliss," and though that sterilizer Plato hates the idea, heaven may well be an orgy. Look at the company Michelangelo's God keeps:

Seven Movie Lines"They call me Moose on accounta I'm large."—Murder, My Sweet

"Insult her. If she's a tramp, she'll get angry; if she's a lady, she'll smile."—Vivre sa vie

"Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don't know."—Camus's L’étranger, Visconti's film

"Desire is always stronger than any virtue. Satan, ora pro nobis."—The Convent

"Trying to guess her weight?"—Baby catching Bogie with a woman in his arms in To Have and Have Not

Dean: “Where’s my drink?” Frank: “In your hand.” Dean: “Is that my hand?”—some Rat Pack movie

"And waiter, do you see that moon? I want to see that moon in the champagne."—Trouble in Paradise

Seven MusicalsThe Smiling Lieutenant, 42nd Street, The Merry Widow, Gold Diggers of 1935, Pal Joey, Black Orpheus, My Fair Lady. Any musical choreographed by Busby Berkeley is bound to be rich in the subtlest and the most obscene pleasures. My own sense of tragedy, such as it is, comes from his Lullaby of Broadway. Like Mozart he is proof that the refined and the vulgar hold hands.

Seven Operas

"The three finest things God ever made are Hamlet, Don Giovanni and the sea."—Gustave FlaubertThe Barber of Seville, The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte, The Magic Flute, La Traviata (by Cotrubas and Domingo, I beg you), Gianni Schicchi. OK, the Verdi and the Puccini suffer from post-Dickensian scmaltz. I've seen/read/heard the story of Camille so often that it seems safe; Don Giovanni is dangerous, as is Hamlet, as is the sea. Nevertheless, the music of Verdi and Puccini is undeniably gorgeous.

All thought aspires to the condition of aria. Imagine allowing your soul to sing—to sing your sins to your confessor, your worries to your psychiatrist, your passion to your lover, your despair—the greatest of human pleasures—to whoever. But no, despair is denied us; there are always other tables to bet at; the universe, as Tennessee Williams said, is a great big gambling casino.

All thought aspires to the condition of aria. Imagine allowing your soul to sing—to sing your sins to your confessor, your worries to your psychiatrist, your passion to your lover, your despair—the greatest of human pleasures—to whoever. But no, despair is denied us; there are always other tables to bet at; the universe, as Tennessee Williams said, is a great big gambling casino.

Opera is the Catholic art, the art of confession. "Do not speak to the driver," says a sign on an Italian bus, "he has to keep his hands on the wheel." What, I have wondered elsewhere, would Protestant opera sound like? It would sound like Wagner, the end of melody, the end of pleasure.

Opera is the Catholic art, the art of confession. "Do not speak to the driver," says a sign on an Italian bus, "he has to keep his hands on the wheel." What, I have wondered elsewhere, would Protestant opera sound like? It would sound like Wagner, the end of melody, the end of pleasure.

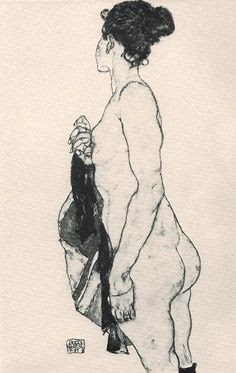

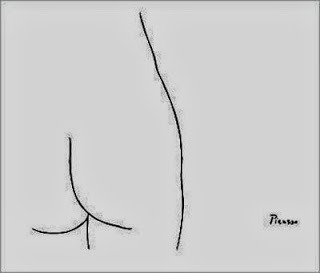

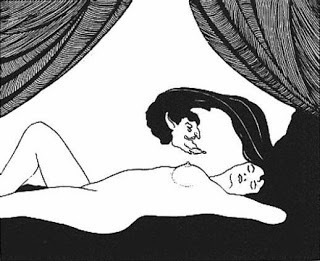

Seven Drawings Opera is not amoral, it is quite deliberately immoral, in the Christian sense: it is pagan. The Bonn-born Beethoven was shocked when he first heard Così fan tutte ("You can live without love, but not without lovers"), and wrote the unsingable and, for those with my pain threshold, the unhearable Fidelio.

Opera is not amoral, it is quite deliberately immoral, in the Christian sense: it is pagan. The Bonn-born Beethoven was shocked when he first heard Così fan tutte ("You can live without love, but not without lovers"), and wrote the unsingable and, for those with my pain threshold, the unhearable Fidelio.

The nordic Protestant Richard Wagner killed opera dead. Moralism, sentimantality (the two are the same: Wagner wrote Here Comes the Bride), Christianity, gnosticism, all kinds of puritanism, and to go with them, atonal music. Verdi the sentimentalist fell in love with Wagner the moralist, and that finished it. Check Philip Glass for the current state of the art. In The President's Palm Reader a hostess asks Word what he thinks of the New Music: "It's great!" he says; "You can hum a tune while you're listening to it!"

The nordic Protestant Richard Wagner killed opera dead. Moralism, sentimantality (the two are the same: Wagner wrote Here Comes the Bride), Christianity, gnosticism, all kinds of puritanism, and to go with them, atonal music. Verdi the sentimentalist fell in love with Wagner the moralist, and that finished it. Check Philip Glass for the current state of the art. In The President's Palm Reader a hostess asks Word what he thinks of the New Music: "It's great!" he says; "You can hum a tune while you're listening to it!"

The Magnificent SevenLouis, Cole, Django, Stéphane, Henry, Nino, Miles. After Wagner flushed melody it was up to Louis and Cole to fish it out and get it dancing again. Louis Armstrong is gorgeousness, the gorgeousest of all musicians, a poet with three voices—his composer's voice, his unmistakable flat-out in-your-face trumpet, and his voice voice which, with Domingo's, is the best male one we have. He taught Ella; he taught Frank; he created American music. Emerson put Shakespeare down because he was a mere entertainer, but entertainment is everything.

Miles Davis, after departing the Kind of Blue mode ("I have no feel for it anymore—it's more like warmed-over turkey") was Wagner's grandchild. Bitches Brew doesn't resolve musically, so it doesn't live in your memory; you recall only a phantasmagorical present. It's the closest thing there is to illegal music. But as with Beethoven and Nabokov, I feel with Davis that I'm in the presence of a bully—and yet not with Hemingway!

Miles Davis, after departing the Kind of Blue mode ("I have no feel for it anymore—it's more like warmed-over turkey") was Wagner's grandchild. Bitches Brew doesn't resolve musically, so it doesn't live in your memory; you recall only a phantasmagorical present. It's the closest thing there is to illegal music. But as with Beethoven and Nabokov, I feel with Davis that I'm in the presence of a bully—and yet not with Hemingway!

Seven WesternsI hate Westerns! Except sometimes: Stagecoach, Shane, The Professionals, The Good the Bad and the Ugly, The Wild Bunch, The Ballad of Cable Hogue, The Outlaw Josey Wales. Ford's hypnotic framing is always wasted on the most pedestrian subjects. The Professionals is the best of them all: "You bastard!" "Yes, sir, by an accident of birth. But you, you're a self-made man."

The Wild Bunch owes it everything, but one must admire those god-men who so bestride the world. Of course I have no interest in machismo—I can barely get the plug out of the hot-water bottle—and when Peckinpah eases up on it, as in The Ballad of Cable Hogue, he makes real poetry. Eastwood I contemplated in the Lubitsch piece.

Leone is the most shamelessly intellectual of them. He must have been shocked at the popularity of that work of semiotics and film criticism, A Fistful of Dollars. It founded an entire genre. His title The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is a gloss on Wittgenstein's "Ethics and aesthetics are one," but the meat is a historical analysis of the industrial revolution and the Western's time in history: the cowboy and the gunfighter thrive between the Civil War and the arrival of the steam engine, and that train is always being built in his movies. Witness the scene where Eli Wallach assembles his pistol out of interchangeable parts. Heavy stuff, and off-putting if you're not hip to his mid-century out-Godard-Godard sensibility.

Leone is the most shamelessly intellectual of them. He must have been shocked at the popularity of that work of semiotics and film criticism, A Fistful of Dollars. It founded an entire genre. His title The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is a gloss on Wittgenstein's "Ethics and aesthetics are one," but the meat is a historical analysis of the industrial revolution and the Western's time in history: the cowboy and the gunfighter thrive between the Civil War and the arrival of the steam engine, and that train is always being built in his movies. Witness the scene where Eli Wallach assembles his pistol out of interchangeable parts. Heavy stuff, and off-putting if you're not hip to his mid-century out-Godard-Godard sensibility.

Which reminds me:

Which reminds me:

Seven More MoviesPickup on South Street, The Seven Samurai, Contempt, Death in Venice, Happy New Year, The Night Porter, The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover. In the sixties Lelouch's A Man and a Woman was the movie of romance; now it's embarrassing to watch. His gem is Happy New Year, a beautifully controlled romantic heist, worth it alone for the pre-Steadicam hand-held one-shot scene in which Lino Ventura, fresh out of jail, cases his mistress's place and slips out when her new boyfriend arrives.

Seven Desperadoes"The beautiful is that which fills us with despair."—Paul Valéry

"All our final decisions are made in a state of mind that is not going to last."—Marcel Proust

"It’s not true that a woman can change a man. I don't want to tell another lie."—8½

"It would be better if nothing existed."—Mephistopheles in Goethe's Faust

"Even damnation is poisoned with rainbows."—Leonard Cohen

We sink in the sweet quicksand of Shakespeare. Perhaps the secret of his haunting voice is the despair in it, the dying fall, the tragic joy. One must look hard to find a triumphant character in him; perhaps only Rosalind sweeps the board. (Do yourself a favor and see the Elizabeth Bergner version.) He teaches us how to be no one.

"Devotion is a kind of despair, and only in despair can we find happiness, which is why I will not deprive myself of my abandonment by the man I love."—Agustina Bessa-Luís, Party

"Devotion is a kind of despair, and only in despair can we find happiness, which is why I will not deprive myself of my abandonment by the man I love."—Agustina Bessa-Luís, Party

Tragic, comic, who cares; what matters is gorgeousness. I said that there have been no poems recently, but Portuguese Agustina Bessa-Luís, who scripted the best de Oliveira's films, Party and The Convent, does the real thing. Alas, I am unable to find translations of her books and am confined to subtitles in her movies, which are of an aristocratic gorgeousness alien to what one of her characters calls "the democracies."

Which reminds me—

A Further Seven Films

The Pink Panther (the original), Charade, How to Steal a Million (such exuberance!), Some Like It Hot, Toby Dammit, La jetée, The Convent. I've seen The Convent two dozen times—but don't go in there expecting a movie movie. These people don't give a damn about what we expect. Ah, to be financed like that!

Pop Music?No. Too gospel-derived. Repent! Atone! The day of judgment is nigh! "And one of these days, baby, and it won't be long, you gonna come back crawlin on yo knees, and you gone be sayin, I still love you! Always thinkin of you! I still love, love, love—" Get lost. It gives rise to the uneasy spectacle of Presbyterians dancing. Gorgeousness is not a judgement, it's an appetite.

Elvis, yes—no brains, but a genius, and a gorgeous one. Johnny Cash, OK, I can't say no to the lyric poet of the American South. "When I was just a baby, my mama told me, Son, Always be a good boy, don't ever play with guns. I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die. When I hear that whistle blowing, I hang my head and cry." If shooting a man to watch him die doesn't do it to you, what that sight has to do with the sound of a train whistle—Pow. Wham. Gotcha.

Seven FoolsChaplin, Keaton, Laurel, Hardy, Alberto Sordi, Lucy, Jackie Gleason. If I were listing actors Gleason would be at the top, with Mickey Rooney, James Mason—I can't think who else now. Michel Piccoli.

A fool is without dignity. A fool sees through dignity. A fool has no use for dignity, except to puncture it. Especially his own.

If you make a fool of yourself deliberately, it’s a triumph. If you make a fool of yourself and it’s not deliberate, it’s humiliating. If it’s deliberate but people think it’s not deliberate, it’s still humiliating—so important is the opinion of others—to me, anyway, but then I’m a fool. The great fools brave this double edge and go all the way into being fools. They live without approval. Not easy.

It's like being ugly. It is being ugly. At the end of City Lights the blind flower girl, her sight restored, looks up at the hero who has done this for her and sees—Charlie. Ooh, bad moment.

Do I see myself as a fool? Only of the undeliberate kind. To be a fool is a holy calling.

Seven DessertsCrêpe Suzette, zabaglione, mousse au chocolat, strawberry cheesecake, bananas in white wine, fudge cake, Tia Maria on vanilla ice cream. Each of these is in its own way a dehumanizing experience, like good sex, and should be preceded by foie gras with Sauternes, and then lobster and champagne (champagne goes with any sea food, I find), followed by a Bûcheron chèvre with Pouilly-Fumé. Or substitute for the lobster a filet de bœuf served raw and in pieces to be grilled on your own heated iron—I love it when they give you those—with a red Bordeaux. And try to control yourself.

Toby's Seven Favorite PleasuresMy alter-ego, lazy worthless Toby Tucker, hero of my comic novels, has, for preference, these:

I lay there, nudged by the lightest possible stirrings of current, waving like seaweed. Here, I congratulated myself, I could combine two of the pleasures afforded by the mortal coil: sleep and immersion in a liquid. Ingestion, elimination, gossiping, shopping for shoes, driving around listening to The Doors and making uh-uh would, for the moment, just have to wait.

Which is eight, actually, not seven. But that's Toby.

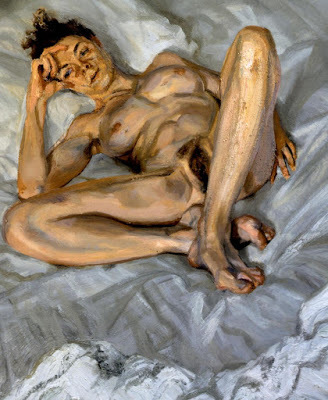

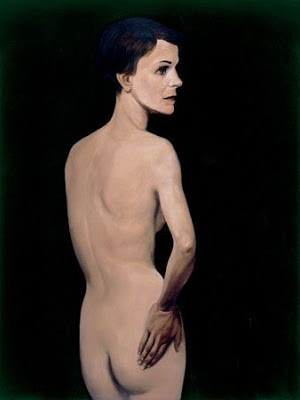

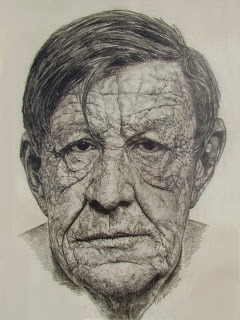

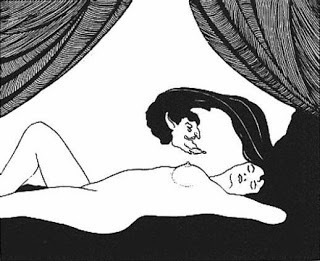

PS: Roman Tsivkin, a man of deeper culture than my own, was gracious enough to praise this piece, even while correcting me on Shostakovich, whose work I list among things ungorgeous. ‘If anything,’ says Roman, ‘his music should have the designation "ugly beauty"’ [pretty much what I feel about the above Rouault painting of the prostitute]. He sent me to hear Shostakovich's Cello Concerto No. 1, which has all the Russian passion you could ask for (there’s nice camera work in the film on YouTube), his 7th Symphony and his jazz waltzes. And I have learned a new pleasure, for which I’m grateful.

Toby books:

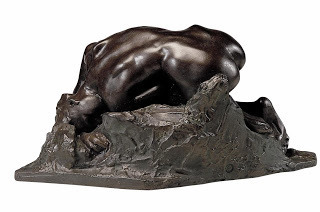

Seven Sculptures

The word is from the French for throat, so let Nefertiti be its patroness. This likeness is from five hundred years before Homer—who says the Greeks invented sculpture? Beautiful women, fully alive, have declined to be in the same room with her, so as not to suffer comparison.

The word is from the French for throat, so let Nefertiti be its patroness. This likeness is from five hundred years before Homer—who says the Greeks invented sculpture? Beautiful women, fully alive, have declined to be in the same room with her, so as not to suffer comparison.

Seven SeasHomer, Scheherazade, Dante, Boccaccio, Rabelais, Montaigne, Shakespeare.

Seven FilmsTrouble in Paradise, To Be or Not to Be (the Lubitsch version), Ninotchka, La Dolce Vita, 8 ½, Satiricon, Party (de Oliveira's).

Seven Novels

Satyricon, Crime and Punishment, In Search of Lost Time, Ulysses, The Great Gatsby ("there was something gorgeous about him"), Under the Volcano, Lolita.

Seven BeautiesSophia; Audrey; Brigitte; Ann-Margret; Sylva; OK, Marilyn; and yes, Joan:

All of them are from the P7 sixties—the post-penicillin, pregnancy-prevention-pill, post-puberty sixties, when sex was just being invented. Polymorphous perverse sex, I mean, and these women embodied it. In The Seven Year Itch Marilyn handles a heat wave by keeping her panties in the ice box.

All of them are from the P7 sixties—the post-penicillin, pregnancy-prevention-pill, post-puberty sixties, when sex was just being invented. Polymorphous perverse sex, I mean, and these women embodied it. In The Seven Year Itch Marilyn handles a heat wave by keeping her panties in the ice box.

Then came the aphrodisiac drugs (Blake predicted "an improvement of sensual enjoyment" around that time)—and scarcely a decade later, the new diseases. Now we don't have sex any more, not with other people, especially when we're married ("If you are afraid of loneliness," said Chekhov, "do not marry"), and have taught ourselves new desires, new ambitions, rather grotesque ones in my opinion. O Hamlet, what a falling-off was there!

Then came the aphrodisiac drugs (Blake predicted "an improvement of sensual enjoyment" around that time)—and scarcely a decade later, the new diseases. Now we don't have sex any more, not with other people, especially when we're married ("If you are afraid of loneliness," said Chekhov, "do not marry"), and have taught ourselves new desires, new ambitions, rather grotesque ones in my opinion. O Hamlet, what a falling-off was there!

Seven Ungorgeous ThingsMusic by Shostakovich; paintings by Jackson Pollock; German food (except for bratwurst); British food (except for fish 'n' chips); prose by Stephen King, Bret Easton Ellis and Jay McInerney (I think they're all the same guy); California wine, unless nothing else is available—unless zero is available; milk.

Seven Ungorgeous ThingsMusic by Shostakovich; paintings by Jackson Pollock; German food (except for bratwurst); British food (except for fish 'n' chips); prose by Stephen King, Bret Easton Ellis and Jay McInerney (I think they're all the same guy); California wine, unless nothing else is available—unless zero is available; milk.Seven Paintings

Catholicism and Hinduism are gorgeous. Judaism, Islam, Protestantism—well. It seems you have to be polytheistic to be gorgeous. Being Catholic is a matter of infinite complications; being Protestant, of stark simplicities. The problem the Germans (pity them!) are having with the Greeks right now is one of infinite complications.

Catholicism and Hinduism are gorgeous. Judaism, Islam, Protestantism—well. It seems you have to be polytheistic to be gorgeous. Being Catholic is a matter of infinite complications; being Protestant, of stark simplicities. The problem the Germans (pity them!) are having with the Greeks right now is one of infinite complications.

We've been surrounded by puritan imagery for two hundred years, Wordsworth's God brooding in solitude over the abyss. Homer's gods "dwell in bliss," and though that sterilizer Plato hates the idea, heaven may well be an orgy. Look at the company Michelangelo's God keeps:

We've been surrounded by puritan imagery for two hundred years, Wordsworth's God brooding in solitude over the abyss. Homer's gods "dwell in bliss," and though that sterilizer Plato hates the idea, heaven may well be an orgy. Look at the company Michelangelo's God keeps:

Seven Movie Lines"They call me Moose on accounta I'm large."—Murder, My Sweet

"Insult her. If she's a tramp, she'll get angry; if she's a lady, she'll smile."—Vivre sa vie

"Mother died today. Or maybe yesterday, I don't know."—Camus's L’étranger, Visconti's film

"Desire is always stronger than any virtue. Satan, ora pro nobis."—The Convent

"Trying to guess her weight?"—Baby catching Bogie with a woman in his arms in To Have and Have Not

Dean: “Where’s my drink?” Frank: “In your hand.” Dean: “Is that my hand?”—some Rat Pack movie

"And waiter, do you see that moon? I want to see that moon in the champagne."—Trouble in Paradise

Seven MusicalsThe Smiling Lieutenant, 42nd Street, The Merry Widow, Gold Diggers of 1935, Pal Joey, Black Orpheus, My Fair Lady. Any musical choreographed by Busby Berkeley is bound to be rich in the subtlest and the most obscene pleasures. My own sense of tragedy, such as it is, comes from his Lullaby of Broadway. Like Mozart he is proof that the refined and the vulgar hold hands.

Seven Operas

"The three finest things God ever made are Hamlet, Don Giovanni and the sea."—Gustave FlaubertThe Barber of Seville, The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte, The Magic Flute, La Traviata (by Cotrubas and Domingo, I beg you), Gianni Schicchi. OK, the Verdi and the Puccini suffer from post-Dickensian scmaltz. I've seen/read/heard the story of Camille so often that it seems safe; Don Giovanni is dangerous, as is Hamlet, as is the sea. Nevertheless, the music of Verdi and Puccini is undeniably gorgeous.

All thought aspires to the condition of aria. Imagine allowing your soul to sing—to sing your sins to your confessor, your worries to your psychiatrist, your passion to your lover, your despair—the greatest of human pleasures—to whoever. But no, despair is denied us; there are always other tables to bet at; the universe, as Tennessee Williams said, is a great big gambling casino.

All thought aspires to the condition of aria. Imagine allowing your soul to sing—to sing your sins to your confessor, your worries to your psychiatrist, your passion to your lover, your despair—the greatest of human pleasures—to whoever. But no, despair is denied us; there are always other tables to bet at; the universe, as Tennessee Williams said, is a great big gambling casino.

Opera is the Catholic art, the art of confession. "Do not speak to the driver," says a sign on an Italian bus, "he has to keep his hands on the wheel." What, I have wondered elsewhere, would Protestant opera sound like? It would sound like Wagner, the end of melody, the end of pleasure.

Opera is the Catholic art, the art of confession. "Do not speak to the driver," says a sign on an Italian bus, "he has to keep his hands on the wheel." What, I have wondered elsewhere, would Protestant opera sound like? It would sound like Wagner, the end of melody, the end of pleasure. Seven Drawings

Opera is not amoral, it is quite deliberately immoral, in the Christian sense: it is pagan. The Bonn-born Beethoven was shocked when he first heard Così fan tutte ("You can live without love, but not without lovers"), and wrote the unsingable and, for those with my pain threshold, the unhearable Fidelio.

Opera is not amoral, it is quite deliberately immoral, in the Christian sense: it is pagan. The Bonn-born Beethoven was shocked when he first heard Così fan tutte ("You can live without love, but not without lovers"), and wrote the unsingable and, for those with my pain threshold, the unhearable Fidelio.

The nordic Protestant Richard Wagner killed opera dead. Moralism, sentimantality (the two are the same: Wagner wrote Here Comes the Bride), Christianity, gnosticism, all kinds of puritanism, and to go with them, atonal music. Verdi the sentimentalist fell in love with Wagner the moralist, and that finished it. Check Philip Glass for the current state of the art. In The President's Palm Reader a hostess asks Word what he thinks of the New Music: "It's great!" he says; "You can hum a tune while you're listening to it!"

The nordic Protestant Richard Wagner killed opera dead. Moralism, sentimantality (the two are the same: Wagner wrote Here Comes the Bride), Christianity, gnosticism, all kinds of puritanism, and to go with them, atonal music. Verdi the sentimentalist fell in love with Wagner the moralist, and that finished it. Check Philip Glass for the current state of the art. In The President's Palm Reader a hostess asks Word what he thinks of the New Music: "It's great!" he says; "You can hum a tune while you're listening to it!"

The Magnificent SevenLouis, Cole, Django, Stéphane, Henry, Nino, Miles. After Wagner flushed melody it was up to Louis and Cole to fish it out and get it dancing again. Louis Armstrong is gorgeousness, the gorgeousest of all musicians, a poet with three voices—his composer's voice, his unmistakable flat-out in-your-face trumpet, and his voice voice which, with Domingo's, is the best male one we have. He taught Ella; he taught Frank; he created American music. Emerson put Shakespeare down because he was a mere entertainer, but entertainment is everything.

Miles Davis, after departing the Kind of Blue mode ("I have no feel for it anymore—it's more like warmed-over turkey") was Wagner's grandchild. Bitches Brew doesn't resolve musically, so it doesn't live in your memory; you recall only a phantasmagorical present. It's the closest thing there is to illegal music. But as with Beethoven and Nabokov, I feel with Davis that I'm in the presence of a bully—and yet not with Hemingway!

Miles Davis, after departing the Kind of Blue mode ("I have no feel for it anymore—it's more like warmed-over turkey") was Wagner's grandchild. Bitches Brew doesn't resolve musically, so it doesn't live in your memory; you recall only a phantasmagorical present. It's the closest thing there is to illegal music. But as with Beethoven and Nabokov, I feel with Davis that I'm in the presence of a bully—and yet not with Hemingway!

Seven WesternsI hate Westerns! Except sometimes: Stagecoach, Shane, The Professionals, The Good the Bad and the Ugly, The Wild Bunch, The Ballad of Cable Hogue, The Outlaw Josey Wales. Ford's hypnotic framing is always wasted on the most pedestrian subjects. The Professionals is the best of them all: "You bastard!" "Yes, sir, by an accident of birth. But you, you're a self-made man."

The Wild Bunch owes it everything, but one must admire those god-men who so bestride the world. Of course I have no interest in machismo—I can barely get the plug out of the hot-water bottle—and when Peckinpah eases up on it, as in The Ballad of Cable Hogue, he makes real poetry. Eastwood I contemplated in the Lubitsch piece.

Leone is the most shamelessly intellectual of them. He must have been shocked at the popularity of that work of semiotics and film criticism, A Fistful of Dollars. It founded an entire genre. His title The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is a gloss on Wittgenstein's "Ethics and aesthetics are one," but the meat is a historical analysis of the industrial revolution and the Western's time in history: the cowboy and the gunfighter thrive between the Civil War and the arrival of the steam engine, and that train is always being built in his movies. Witness the scene where Eli Wallach assembles his pistol out of interchangeable parts. Heavy stuff, and off-putting if you're not hip to his mid-century out-Godard-Godard sensibility.

Leone is the most shamelessly intellectual of them. He must have been shocked at the popularity of that work of semiotics and film criticism, A Fistful of Dollars. It founded an entire genre. His title The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is a gloss on Wittgenstein's "Ethics and aesthetics are one," but the meat is a historical analysis of the industrial revolution and the Western's time in history: the cowboy and the gunfighter thrive between the Civil War and the arrival of the steam engine, and that train is always being built in his movies. Witness the scene where Eli Wallach assembles his pistol out of interchangeable parts. Heavy stuff, and off-putting if you're not hip to his mid-century out-Godard-Godard sensibility. Which reminds me:

Which reminds me:Seven More MoviesPickup on South Street, The Seven Samurai, Contempt, Death in Venice, Happy New Year, The Night Porter, The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover. In the sixties Lelouch's A Man and a Woman was the movie of romance; now it's embarrassing to watch. His gem is Happy New Year, a beautifully controlled romantic heist, worth it alone for the pre-Steadicam hand-held one-shot scene in which Lino Ventura, fresh out of jail, cases his mistress's place and slips out when her new boyfriend arrives.

Seven Desperadoes"The beautiful is that which fills us with despair."—Paul Valéry

"All our final decisions are made in a state of mind that is not going to last."—Marcel Proust

"It’s not true that a woman can change a man. I don't want to tell another lie."—8½

"It would be better if nothing existed."—Mephistopheles in Goethe's Faust

"Even damnation is poisoned with rainbows."—Leonard Cohen

We sink in the sweet quicksand of Shakespeare. Perhaps the secret of his haunting voice is the despair in it, the dying fall, the tragic joy. One must look hard to find a triumphant character in him; perhaps only Rosalind sweeps the board. (Do yourself a favor and see the Elizabeth Bergner version.) He teaches us how to be no one.

"Devotion is a kind of despair, and only in despair can we find happiness, which is why I will not deprive myself of my abandonment by the man I love."—Agustina Bessa-Luís, Party

"Devotion is a kind of despair, and only in despair can we find happiness, which is why I will not deprive myself of my abandonment by the man I love."—Agustina Bessa-Luís, PartyTragic, comic, who cares; what matters is gorgeousness. I said that there have been no poems recently, but Portuguese Agustina Bessa-Luís, who scripted the best de Oliveira's films, Party and The Convent, does the real thing. Alas, I am unable to find translations of her books and am confined to subtitles in her movies, which are of an aristocratic gorgeousness alien to what one of her characters calls "the democracies."

Which reminds me—

A Further Seven Films

The Pink Panther (the original), Charade, How to Steal a Million (such exuberance!), Some Like It Hot, Toby Dammit, La jetée, The Convent. I've seen The Convent two dozen times—but don't go in there expecting a movie movie. These people don't give a damn about what we expect. Ah, to be financed like that!

Pop Music?No. Too gospel-derived. Repent! Atone! The day of judgment is nigh! "And one of these days, baby, and it won't be long, you gonna come back crawlin on yo knees, and you gone be sayin, I still love you! Always thinkin of you! I still love, love, love—" Get lost. It gives rise to the uneasy spectacle of Presbyterians dancing. Gorgeousness is not a judgement, it's an appetite.

Elvis, yes—no brains, but a genius, and a gorgeous one. Johnny Cash, OK, I can't say no to the lyric poet of the American South. "When I was just a baby, my mama told me, Son, Always be a good boy, don't ever play with guns. I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die. When I hear that whistle blowing, I hang my head and cry." If shooting a man to watch him die doesn't do it to you, what that sight has to do with the sound of a train whistle—Pow. Wham. Gotcha.

Seven FoolsChaplin, Keaton, Laurel, Hardy, Alberto Sordi, Lucy, Jackie Gleason. If I were listing actors Gleason would be at the top, with Mickey Rooney, James Mason—I can't think who else now. Michel Piccoli.

A fool is without dignity. A fool sees through dignity. A fool has no use for dignity, except to puncture it. Especially his own.

If you make a fool of yourself deliberately, it’s a triumph. If you make a fool of yourself and it’s not deliberate, it’s humiliating. If it’s deliberate but people think it’s not deliberate, it’s still humiliating—so important is the opinion of others—to me, anyway, but then I’m a fool. The great fools brave this double edge and go all the way into being fools. They live without approval. Not easy.

It's like being ugly. It is being ugly. At the end of City Lights the blind flower girl, her sight restored, looks up at the hero who has done this for her and sees—Charlie. Ooh, bad moment.

Do I see myself as a fool? Only of the undeliberate kind. To be a fool is a holy calling.

Seven DessertsCrêpe Suzette, zabaglione, mousse au chocolat, strawberry cheesecake, bananas in white wine, fudge cake, Tia Maria on vanilla ice cream. Each of these is in its own way a dehumanizing experience, like good sex, and should be preceded by foie gras with Sauternes, and then lobster and champagne (champagne goes with any sea food, I find), followed by a Bûcheron chèvre with Pouilly-Fumé. Or substitute for the lobster a filet de bœuf served raw and in pieces to be grilled on your own heated iron—I love it when they give you those—with a red Bordeaux. And try to control yourself.

Toby's Seven Favorite PleasuresMy alter-ego, lazy worthless Toby Tucker, hero of my comic novels, has, for preference, these:

I lay there, nudged by the lightest possible stirrings of current, waving like seaweed. Here, I congratulated myself, I could combine two of the pleasures afforded by the mortal coil: sleep and immersion in a liquid. Ingestion, elimination, gossiping, shopping for shoes, driving around listening to The Doors and making uh-uh would, for the moment, just have to wait.

Which is eight, actually, not seven. But that's Toby.

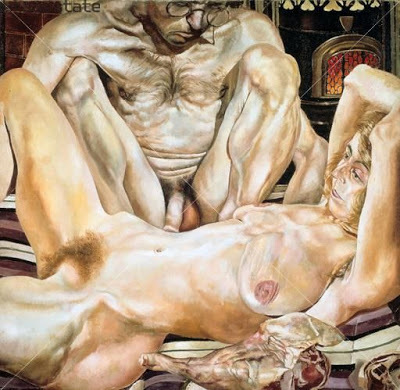

PS: Roman Tsivkin, a man of deeper culture than my own, was gracious enough to praise this piece, even while correcting me on Shostakovich, whose work I list among things ungorgeous. ‘If anything,’ says Roman, ‘his music should have the designation "ugly beauty"’ [pretty much what I feel about the above Rouault painting of the prostitute]. He sent me to hear Shostakovich's Cello Concerto No. 1, which has all the Russian passion you could ask for (there’s nice camera work in the film on YouTube), his 7th Symphony and his jazz waltzes. And I have learned a new pleasure, for which I’m grateful.

Toby books:

Published on November 21, 2013 08:11

June 27, 2013

Hitch and Cary: A Study in Charm

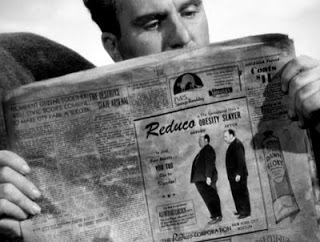

"Even Cary Grant isn’t Cary Grant."—Cary GrantGrant and Hitchcock—not exactly identical twins, but the same kind of guy, really. They had charm. "Thin people," Jackie Gleason said, "are beautiful, but fat people are adorable." Hitchcock seems to have agreed. "In England," he said when he got to Hollywood, "everybody looks like this." He does his de rigueur cameo in Lifeboat, with its confined setting, in a weight-reducing ad. He's the one on the left. Neither of these blubber-bellies ever got serious about dieting.

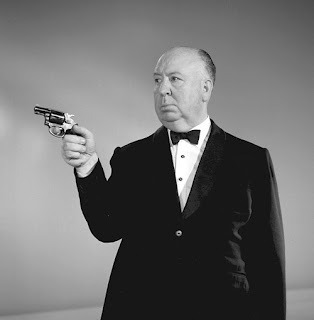

"Even Cary Grant isn’t Cary Grant."—Cary GrantGrant and Hitchcock—not exactly identical twins, but the same kind of guy, really. They had charm. "Thin people," Jackie Gleason said, "are beautiful, but fat people are adorable." Hitchcock seems to have agreed. "In England," he said when he got to Hollywood, "everybody looks like this." He does his de rigueur cameo in Lifeboat, with its confined setting, in a weight-reducing ad. He's the one on the left. Neither of these blubber-bellies ever got serious about dieting.  As the television host of Alfred Hitchcock Presents he came into our living rooms every Sunday night with perfect British aplomb, the merry mock-lugubrious image of sophistication. "Good evening," he always began.

As the television host of Alfred Hitchcock Presents he came into our living rooms every Sunday night with perfect British aplomb, the merry mock-lugubrious image of sophistication. "Good evening," he always began.

"Television has brought murder back into the home," he said, "where it belongs." Like Grant he was a symbol, in America, of debonair elegance. Not your average food-on-the-teeth Brit.

"Television has brought murder back into the home," he said, "where it belongs." Like Grant he was a symbol, in America, of debonair elegance. Not your average food-on-the-teeth Brit.

Back home, though, he was lower-class. When he worked in England, even as late as Stage Fright in 1950, his actors complained that they couldn’t understand him through his Cockney accent. And notice, when he goes into the houses of the rich, how the camera always stays downstairs looking up at a world into which it dare not intrude. Strangers on a Train and Marnie fly to mind; here's Rebecca:

Back home, though, he was lower-class. When he worked in England, even as late as Stage Fright in 1950, his actors complained that they couldn’t understand him through his Cockney accent. And notice, when he goes into the houses of the rich, how the camera always stays downstairs looking up at a world into which it dare not intrude. Strangers on a Train and Marnie fly to mind; here's Rebecca: And Grant, real name Archie Leach, was, class-wise, Hitchcock's Bristol equivalent. He worried all his life that he lacked the background for what he was supposed to be.

And Grant, real name Archie Leach, was, class-wise, Hitchcock's Bristol equivalent. He worried all his life that he lacked the background for what he was supposed to be.  Both, despite their enormous success, were always slightly out of place in the US. Hitchcock's American films, though his obsession with detail is inspiring, never seem to me to be quite American: the people are too mild, too mannerly—too British. Even his salesclerks are polite—chatty without being intrusive. There is never the undercurrent of physical threat that haunts American movies, and indeed American life. Murder and psychopathology are there all right but they're disguised, as they are in Agatha Christie, not, as in the United States, a matter of style.

Both, despite their enormous success, were always slightly out of place in the US. Hitchcock's American films, though his obsession with detail is inspiring, never seem to me to be quite American: the people are too mild, too mannerly—too British. Even his salesclerks are polite—chatty without being intrusive. There is never the undercurrent of physical threat that haunts American movies, and indeed American life. Murder and psychopathology are there all right but they're disguised, as they are in Agatha Christie, not, as in the United States, a matter of style.

Same goes for Grant: he was never all the way American. Imagine him getting angry. Impossible. Anger is the opposite of charm. Anger says things aren't going your way. Everything went his way, except when it didn't, in which case he ran like hell. Scarcely an American hero.

Same goes for Grant: he was never all the way American. Imagine him getting angry. Impossible. Anger is the opposite of charm. Anger says things aren't going your way. Everything went his way, except when it didn't, in which case he ran like hell. Scarcely an American hero.

Part fool, part coward, is what he was, and here I am at one with him. Punch somebody? No no no. When it comes to a fight, as in Charade, he allows the George-Kennedy giant to defeat himself, then lectures him on loving thy neighbor—though that wasn't entirely his policy. Fuck you, I'm Cary Grant, is more like it.

Part fool, part coward, is what he was, and here I am at one with him. Punch somebody? No no no. When it comes to a fight, as in Charade, he allows the George-Kennedy giant to defeat himself, then lectures him on loving thy neighbor—though that wasn't entirely his policy. Fuck you, I'm Cary Grant, is more like it.

A recent article in The Atlantic, "The Rise and Fall of Charm in American Men," centers of course on Grant, but then shifts the focus to Orson Welles and James Garner—well, all right—but leaves Fred Astaire out entirely! And in predictable Puritan fashion it pronounces a negative judgement on charm: it is "amoral," unAmerican and to be watched out for. Thank God it's gone. Grant may have been gay.

A recent article in The Atlantic, "The Rise and Fall of Charm in American Men," centers of course on Grant, but then shifts the focus to Orson Welles and James Garner—well, all right—but leaves Fred Astaire out entirely! And in predictable Puritan fashion it pronounces a negative judgement on charm: it is "amoral," unAmerican and to be watched out for. Thank God it's gone. Grant may have been gay.And indeed, what would he do in a film by Crapola or Scorsleazy, advertisements, both, that America has run out of decency. It seems clear what he would not do, but what would he do? (For more on this see Italian-American Filmmakers.)

Which brings us to the question of the psychopath. Hitchcock had dealt with psychopaths in his British films, so I don’t know whether it was by insight or by predilection that he so consistently exploited this theme in Hollywood. As a Frenchman in one of my scripts says, "The psychopath is an American tradition since Captain Ahab and poor Mr. Poe. One daren’t make a film without one. Such people are the norm here—corporate conventioneers, fast food waiters, religious fanatics—even the hotel clerks glow with sinister joy. Observe yourselves in television audiences. You are all quite mad!"

A header in yesterday's New York Times: "Once I got pregnant I had to abandon the drugs that made me stable enough to want to be become a mother in the first place." Everybody's a psychopath. When Martin McDonagh came to make an American film he wrote for himself Seven Psychopaths, which, as a strategy, couldn't miss.

A header in yesterday's New York Times: "Once I got pregnant I had to abandon the drugs that made me stable enough to want to be become a mother in the first place." Everybody's a psychopath. When Martin McDonagh came to make an American film he wrote for himself Seven Psychopaths, which, as a strategy, couldn't miss.In Suspicion Grant plays the psychopath, and Hitchcock complained to Francois Truffaut (a man of extraordinary dullness) that he couldn’t end the film the way he wanted to because you can’t make Cary Grant a murderer.

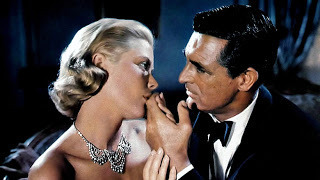

He also told Truffaut that, although he had only made one overt comedy, all of his films were more or less comic. Perhaps this explains why my favorite Hitchcock films are the Cary Grant ones—especially To Catch a Thief and North by Northwest, which to me are romantic comedies—so much so that I’m inclined to regard Grant as their real auteur.

He also told Truffaut that, although he had only made one overt comedy, all of his films were more or less comic. Perhaps this explains why my favorite Hitchcock films are the Cary Grant ones—especially To Catch a Thief and North by Northwest, which to me are romantic comedies—so much so that I’m inclined to regard Grant as their real auteur. Now, please, Hitchcock is a master, for many people the master of cinema, an inventor not just of images—the chase among the umbrellas in Foreign Correspondent, the tennis-game in Strangers on a Train, all faces going back and forth with the ball except the psychopath’s—but of sounds: he was the first to experiment with electronic synthesis in The Birds. (And let's mention casting—George Sanders as a used-car salesman in Rebecca: inspired!)

Now, please, Hitchcock is a master, for many people the master of cinema, an inventor not just of images—the chase among the umbrellas in Foreign Correspondent, the tennis-game in Strangers on a Train, all faces going back and forth with the ball except the psychopath’s—but of sounds: he was the first to experiment with electronic synthesis in The Birds. (And let's mention casting—George Sanders as a used-car salesman in Rebecca: inspired!)

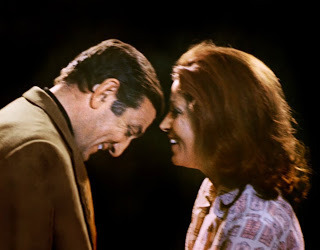

But more than that he could give you the feel of a relationship. James Agee remarked of Notorious that Hichcock was "as good at domestic psychology as at thrillers, and many times he makes a moment in a party, or a lovers' quarrel, or a mere interior shrewdly exciting in ways that few people in films seem to know."

But more than that he could give you the feel of a relationship. James Agee remarked of Notorious that Hichcock was "as good at domestic psychology as at thrillers, and many times he makes a moment in a party, or a lovers' quarrel, or a mere interior shrewdly exciting in ways that few people in films seem to know." One thinks of his silent The Lodger, in which the lovers are endeared to us by their habit of hovering in a restaurant until they can pounce on their favorite table; and of Marnie (where the psychopath, for the first time since Rebecca, is a woman), when Sean Connery’s character tells her that, although marriages are said to succeed or fail in bed, they’re really about control of the bathroom.

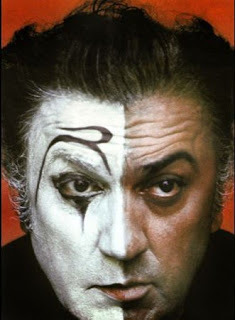

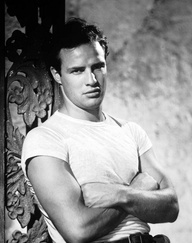

And—this I love—Hitchcock was impatient with Method acting and the Actors Studio, which made Brando the punk and De Niro the lunk high priests of seriousness. ("When you hear the phrase a good acting job," says Toby in one of my books, "it usually means a depressing movie.") As a filmmaker in Europe I always forget what I’m going to confront when I work with an American actor—back story, motivation and cetera, the whole spiritual exercise. (See The "Character Arc", where I really get my rocks off on this.)

And—this I love—Hitchcock was impatient with Method acting and the Actors Studio, which made Brando the punk and De Niro the lunk high priests of seriousness. ("When you hear the phrase a good acting job," says Toby in one of my books, "it usually means a depressing movie.") As a filmmaker in Europe I always forget what I’m going to confront when I work with an American actor—back story, motivation and cetera, the whole spiritual exercise. (See The "Character Arc", where I really get my rocks off on this.) "When an actor comes to me and wants to discuss his character," said Hitchcock, "I say, It's in the script. If he says, But what's my motivation? I say, Your salary." All he wanted Paul Newman to do was hold still for the camera, but no, he was too involved in the part. ("Never do eating scenes with Method actors," said Bogart, "they spit all over you.") "I don't feel like that, I don't think I can give you that kind of emotion," Ingrid Bergman told him. "Ingrid," said Hitch, "fake it."

When an actress asked him which of her profiles was better he said, "My dear, you're sitting on your best profile."His attitude to character is clearest in Psycho: if you kill the heroine in the first act you'd better replace her—and yes, here comes her look-alike sister, thrown so together with the hero that she's set up to be his new squeeze. It's the kind of mix 'n' match you get in A Midsummer Night's Dream and Così fan tutte—whichever partner the dance gives you. But the Puritan must think one self, one love, one moral quest, and God help you if you enjoy it. I'm not a Christian but I did like the way the new Pope ended his first speech: "Have a good lunch."

When an actress asked him which of her profiles was better he said, "My dear, you're sitting on your best profile."His attitude to character is clearest in Psycho: if you kill the heroine in the first act you'd better replace her—and yes, here comes her look-alike sister, thrown so together with the hero that she's set up to be his new squeeze. It's the kind of mix 'n' match you get in A Midsummer Night's Dream and Così fan tutte—whichever partner the dance gives you. But the Puritan must think one self, one love, one moral quest, and God help you if you enjoy it. I'm not a Christian but I did like the way the new Pope ended his first speech: "Have a good lunch." Nor does Hitch care much about connections. Plot, yes, his plots are tight, but he moves us from scene to scene with a beautiful arrogance. In To Catch a Thief policemen stalk Grant's character through a market (where, in Cannes? Nice? Monte Carlo? Hitchcock, usually so careful about place, uses all of them to compose a Riviera town) at an ever faster pace until he upsets a flower stall and the owner snags him by the sweater and won't let him go. "Madame! S'il vous plaît, Madame!" What happens—do the cops arrest him? Do they take him to the station? Do they question him? Hitchcock doesn't care, and neither do we: cut to lunch on the terrace overlooking the village on the sea, with not even the mention of a resolution of the previous scene.

Nor does Hitch care much about connections. Plot, yes, his plots are tight, but he moves us from scene to scene with a beautiful arrogance. In To Catch a Thief policemen stalk Grant's character through a market (where, in Cannes? Nice? Monte Carlo? Hitchcock, usually so careful about place, uses all of them to compose a Riviera town) at an ever faster pace until he upsets a flower stall and the owner snags him by the sweater and won't let him go. "Madame! S'il vous plaît, Madame!" What happens—do the cops arrest him? Do they take him to the station? Do they question him? Hitchcock doesn't care, and neither do we: cut to lunch on the terrace overlooking the village on the sea, with not even the mention of a resolution of the previous scene. Or did he care? Did he, as most filmmakers would, agonize in the editing room over some dull takes he didn't dare slow the film down with? Did he perhaps realize that, like Fellini but in his unique way, he was a master of gorgeousness? We are accustomed to thinking of his art as severe but in that film, as in many others, spectacle was all that interested him.

On the other hand there’s a lot of b.s. about Hitchcock, to some of which he contributed himself. He said things like "If it's a good movie, the sound could go off and the audience would still have a perfectly clear idea of what was going on," and "When the screenplay has been written and the dialogue has been added, we're ready to shoot." Balls. Nobody has committed more bla-bla than Hitchcock. Psycho has three exciting, nay, emotionally scarring scenes, and an hour and a half of yack-yack.

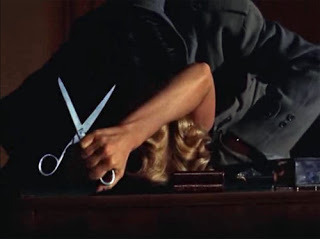

A curious thing happened to this draftsman-cum-storyboarder: long about 1949 (though it might have come as early as Lifeboat) he fell in love with the theatre, and started directing movies as if they were plays. Rope, Stage Fright, Rear Window, The Trouble with Harry—these could all be performed on the stage, and that’s the way he shot them. Dial M for Murder has one exciting visual scene, the scissors in the back; otherwise it’s all dialogue in rooms. And Under Capricorn—oh, God! "Always make the audience suffer as much as possible," he said. Uh-huh.

A curious thing happened to this draftsman-cum-storyboarder: long about 1949 (though it might have come as early as Lifeboat) he fell in love with the theatre, and started directing movies as if they were plays. Rope, Stage Fright, Rear Window, The Trouble with Harry—these could all be performed on the stage, and that’s the way he shot them. Dial M for Murder has one exciting visual scene, the scissors in the back; otherwise it’s all dialogue in rooms. And Under Capricorn—oh, God! "Always make the audience suffer as much as possible," he said. Uh-huh.

In the Grant films the problem disappears—perhaps not so much with Notorious, which, as he told Peter Bogdanovich, "Hitch threw to Ingrid." But in To Catch a Thief and North by Northwest we’re in the world of Cary Grant comedies and buoyed by the Grant charm, which never requires excessive dialogue.

In the Grant films the problem disappears—perhaps not so much with Notorious, which, as he told Peter Bogdanovich, "Hitch threw to Ingrid." But in To Catch a Thief and North by Northwest we’re in the world of Cary Grant comedies and buoyed by the Grant charm, which never requires excessive dialogue.

He's not my favorite actor, I’m not saying that. I prefer the Boyer-Irene Dunne version of An Affair to Remember. (I prefer the Irene Dunne version of anything.) And, here’s an irony, Grant wasn’t as famous as Hitchcock. To quote the above Frenchman, "The very first rank of fame is to be known by your nickname, like Liz and Bogie and Di and Satchmo. The second is to be known by your initials—mainly for American presidents, but Brigitte was BB, which means in French baby, and Marilyn in the headlines became MMM. Then come the first names, Sophia, Marcello, Frank, and fourth are the last names, Garbo and Gable. And fifth…." Well, Cary Grant. Hitch’s nickname was a company-town secret until it got out, but it got out.

He's not my favorite actor, I’m not saying that. I prefer the Boyer-Irene Dunne version of An Affair to Remember. (I prefer the Irene Dunne version of anything.) And, here’s an irony, Grant wasn’t as famous as Hitchcock. To quote the above Frenchman, "The very first rank of fame is to be known by your nickname, like Liz and Bogie and Di and Satchmo. The second is to be known by your initials—mainly for American presidents, but Brigitte was BB, which means in French baby, and Marilyn in the headlines became MMM. Then come the first names, Sophia, Marcello, Frank, and fourth are the last names, Garbo and Gable. And fifth…." Well, Cary Grant. Hitch’s nickname was a company-town secret until it got out, but it got out.

Let's tie this up with Charade, the best film Hitchcock never made. Stanley Donen, he of Singin’ in the Rain and Two for the Road, made it instead. It’s got Grant (hoarse at fifty-nine—why do actors seem to age so quickly?); it’s got the darling Audrey, clearly crazy about him and at her breathiest ("I’m not hungry at all any more, isn’t it marvelous!"); it’s got a score by Henry Mancini, one of the Magnificent Seven (Louis, Cole, Django, Stéphane, Henry, Nino and Miles); it's got Paris, and some nice digs at the French; it's got charm from every possible direction; and it’s got warmth, which you’ll look hard for in Hitchcock.

Let's tie this up with Charade, the best film Hitchcock never made. Stanley Donen, he of Singin’ in the Rain and Two for the Road, made it instead. It’s got Grant (hoarse at fifty-nine—why do actors seem to age so quickly?); it’s got the darling Audrey, clearly crazy about him and at her breathiest ("I’m not hungry at all any more, isn’t it marvelous!"); it’s got a score by Henry Mancini, one of the Magnificent Seven (Louis, Cole, Django, Stéphane, Henry, Nino and Miles); it's got Paris, and some nice digs at the French; it's got charm from every possible direction; and it’s got warmth, which you’ll look hard for in Hitchcock.

But it couldn't have happened without him.

But it couldn't have happened without him. Also by Robert MacLean, the "Toby" books,Will You Please Fuck Off? at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT, Amazon ES and Smashwords;Foreign Matter at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT, Amazon ES and Smashwords; Total Moisture at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT, Amazon ES and Smashwords; The Cad at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT, Amazon ES and Smashwords;and these, too,

Mortal Coil: A Comedy of Corpses at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT and Amazon ES;The President's Palm Reader: A Washington Comedy at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT and Amazon ES; and

Greek Island Murder at Amazon US, Amazon UK, Amazon FR, Amazon DE, Amazon IT and Amazon ES.

Published on June 27, 2013 08:24

December 2, 2012

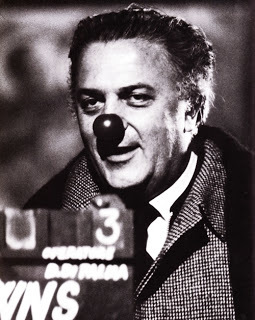

Fellini

“Aesthetic emotion puts man in a state favorable to the reception of erotic emotion. Art is the accomplice of love. Take love away and there is no longer art.”—Remy de Gourmont Theoretically, the perfect movie would combine Ford's framing, Ophuls' staging, Fellini's pacing, Visconti's production values and Lubitsch's wit. But who lines up to see theories?

“Aesthetic emotion puts man in a state favorable to the reception of erotic emotion. Art is the accomplice of love. Take love away and there is no longer art.”—Remy de Gourmont Theoretically, the perfect movie would combine Ford's framing, Ophuls' staging, Fellini's pacing, Visconti's production values and Lubitsch's wit. But who lines up to see theories? We don’t have to ask what the best thing is in any art— everybody knows. What’s the greatest painting if not the Sistine ceiling? The greatest sculpture? The greatest play? The greatest film? Many people who bother to consider such things would say 8 ½; and indeed who is the axiomatic director but Fellini?

So let us stand the greatest play and the greatest film side by side: the melancholy Dane and the melancholy Guido. Eternal high-school kid that I am, I’m always looking for a key to Hamlet. Maybe this is it!

So let us stand the greatest play and the greatest film side by side: the melancholy Dane and the melancholy Guido. Eternal high-school kid that I am, I’m always looking for a key to Hamlet. Maybe this is it!Like Hamlet, Guido is a new kind of man. Hamlet Senior is modeled on Achilles, as heroes had been for millennia, and still are. “Strength and honor” is the salute in Gladiator—the values associated with the heroic, and with pop culture. If you’re not interested in tough guys most cinema is meaningless to you.

The ghost walks in armor, and he expects his son to do the heroic thing, because revenge is the epic motive. Check your TV Guide. But Hamlet just isn’t Achilles. He can’t bring himself to kill Claudius—not that he lacks the murderous impulse. In neighboring Norway Fortinbras, which means “Strong-arm,” is a replica of Fortinbras Senior. Hamlet catches sight of Junior marching his army through Denmark to attack the Poles, and is full of admiration; but like all the masks Hamlet tries on, it just ain’t him. No mask fits Hamlet ("I have that within which passeth show") but he can't represent himself without one. Who can? He is, as Harold Bloom says, something new.

Same goes for Guido, and for all of Fellini’s men. When, in La Dolce Vita, Lex Barker punches Marcello for being out all night with Anita, Paparazzo says, “You’re not going to fight back?” Marcello shakes his head. No machismo for him.

Hamlet and 8 ½ both persuade us that the inner life can be portrayed on the stage, on the screen. We had had to project that innerness onto the gestures and speeches of the actors; these works put it in our face.

Hamlet and 8 ½ both persuade us that the inner life can be portrayed on the stage, on the screen. We had had to project that innerness onto the gestures and speeches of the actors; these works put it in our face. Like Hamlet Guido makes a film within a film, if I may so put it.

Like Hamlet, he lifts his inner torment above the others, and resorts to irony when he deals with them, and indeed with himself. Each of them is understood, in his respective world, by no one.

Like Hamlet Guido is haunted by his father, who climbs out of the grave and complains about the accommodations. “How’s my son doing?” he asks Guido’s producer, but the producer just shakes his head.

Like Hamlet he has an ambiguously erotic relationship with his mother.

Like Hamlet's, Guido's dream girl turns out to be "a little bore," as he calls Claudia.

Like Hamlet (indeed like Shakespeare), his reality is shattered and lies there in pieces. He has no synthetic power but in the vibrancy of each piece. This seems to me a thread in the velvet of Shakespeare's "voice," so to call it, a note of surrender, a dying fall.

Like Hamlet Guido thinks a hundred thoughts, and none of them are really him.

Like Hamlet he’s a comedian, a monologuist, a clown and, like most clowns, a sad one. The pair of them are self-pitying smart-asses.

Hamlet is a refined man. He's been played infinitely differently, and several times by women, as Poldy remarks in Ulysses, but as many ways as we can imagine him, we can't think of him as vulgar. Why not? He is crass, dishonest, rash, cruel, murderous—there's hardly a disgrace he doesn't commit. Ah, but that wit of his. "So is it, if thou knew'st our purposes." "I see a cherub that sees them."

Hamlet is a refined man. He's been played infinitely differently, and several times by women, as Poldy remarks in Ulysses, but as many ways as we can imagine him, we can't think of him as vulgar. Why not? He is crass, dishonest, rash, cruel, murderous—there's hardly a disgrace he doesn't commit. Ah, but that wit of his. "So is it, if thou knew'st our purposes." "I see a cherub that sees them."Same for Guido, who never commits the vulgarity of action; it's all in his mind. Fellini wasn’t happy with Marcello as his alter-ego, and made him have his chest waxed to be more refined. I think he’d have preferred an Alain Delon or an Oskar Werner. “Oh, Maestro, Marcello again?” say the spirits, mocking him (as when do they not?) in City of Women.

Like Hamlet Guido lives in a world of spirits—in his case Italy, where ancient presences from the pagan panoply that underlies Catholicism roam the earth, and know his thoughts. "There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy."

Like Hamlet he's blocked by his contradictions. “And in my heart there was a kind of fighting.” Guido answers yes and no to every possible question. “Do you have children?” says the Cardinal. “Yes, I mean no.” This too is post-heroic. The hero is always yes or no, zero or one: only one man comes back from a gunfight. “Decide, Guido!” his producer shouts as they view the screen tests; “Choose!” Guido can’t. He is not the decider.

At the station he throws away his collaborator’s ruthless critique of his script, then picks it up and reads it again. This is a scene he stole from Buster Keaton (Leone used it too, at the beginning of Once upon a Time in the West): the train leaves, his mistress hasn’t arrived, he’s relieved and gets up to go, but as it pulls out there she is in white fur trimming. “Yoohoo!” He looks around; does anybody see?

Then he takes her back to his room and has her perform his sexual fantasies. For once he’s a director who knows what he wants.

Like Hamlet, Guido knows the self is not socially acceptable. They free us from Christianity—that won’t work for either of them. Hamlet, murderer of men, torturer of women, frees us from sin, negates sin. It no longer matters. Yet we have no doubt of his metaphysical validity. (I don’t want to say “salvation”—Christianity doesn’t work for me either.) The redeemer as smart-ass.

Like Hamlet, Guido knows the self is not socially acceptable. They free us from Christianity—that won’t work for either of them. Hamlet, murderer of men, torturer of women, frees us from sin, negates sin. It no longer matters. Yet we have no doubt of his metaphysical validity. (I don’t want to say “salvation”—Christianity doesn’t work for me either.) The redeemer as smart-ass. And what is Guido if not an impotent god? Both of these men are open-topped. They communicate directly with—what?

Happiness, Guido says, is being able to tell the truth without hurting anybody. His sensuality is all that interests him. He's not a Christian, saints be praised, but he’s Catholic, and confession is part of his style. The screen tests in 8 ½ are confessions to his wife. Everything he does is a confession. When he goes down into the Dante-esque steam room to interview the Cardinal all he can do is confess. “Father, I am not happy.” “You’re not here to be happy,” says the Cardinal with some justice, but then he quotes Origen, the Church Father who castrated himself: “There is no salvation outside the Church.” And there is Guido, outside the Church.

Ah, he’s down. But at the end, the uplift! “What is this flash of joy that’s giving me new life?” I have mentioned elsewhere that the Protestant inclines to schizophrenia, and the Catholic to manic-depression. Guido’s spirits simply lift, and we have his vision of a latter-day Communion of Saints.

But humility, charity—don’t look for them in Hamlet. Don’t look for them in Guido. “He never gives, nor lends, nor trusts,” the feminist judges say of Snaporaz. Early on Fellini worked under the yoke of Neo-Realism, which he subverted at every opportunity. Social reality interested him not even slightly, but it was the only game in town.

In Il Bidone Broderick Crawford plays a con man disguised as a priest. There’s a touching moment when he’s asked to comfort a wheelchair-bound teenager, who tells a sad story. He shrugs—at her, at the whole movement: “You don’t need me. You’re much better off than a lot of other people.” When he and Richard Basehart are milking a village Basehart smiles at an urchin, a perfect Neo-Realist poster, but “You look like a little devil,” he says. Devils are what we seem to be in Fellini. “And the bravest of the devils said ‘I’m going to get into the labyrinth!’” Giulietta tells the kids in Juliet of the Spirits.

Not that he took evil seriously. When the Fascists fill his father full of castor oil, which in fact was their practice, to humiliate him by making him shit himself, the young Fellini, and the older Fellini, think it’s a big joke. An American bombing raid forces him and his Roman hosts from their dining tables in the street into an air-raid shelter; but you can meet some good-looking women down there.

Not that he took evil seriously. When the Fascists fill his father full of castor oil, which in fact was their practice, to humiliate him by making him shit himself, the young Fellini, and the older Fellini, think it’s a big joke. An American bombing raid forces him and his Roman hosts from their dining tables in the street into an air-raid shelter; but you can meet some good-looking women down there.“There’s a divinity that shapes our ends,” Snaporaz quotes in City of Women. I don’t know how deeply the Maestro read in Hamlet—he didn’t like to be thought of as an intellectual. And Toby Dammit, the Englishman in Rome, gives us just enough of Macbeth’s “Tomorrow and tomorrow” to let us know that he’s a tragic Nordic. These schizos; if you want to get where you’re going you can’t take your head.

Most of us think Hamlet is Shakespeare’s greatest work, and 8 ½ Fellini’s. (Thank God for black and white.) (Thank who?) Everything else Fellini did is episodic—breaks into episodes that can be eliminated without affecting the story. This, as Aristotle told us, is bad for business, and relegates those films to what we currently call art-house status. Only plot sells: not beautiful language, not beautiful shots, not beautiful stars; plot. Which is to say because, not and then. The king died and then the queen died, said W.H. Auden, is a story; the king died and then the queen died of grief is a plot.

Most of us think Hamlet is Shakespeare’s greatest work, and 8 ½ Fellini’s. (Thank God for black and white.) (Thank who?) Everything else Fellini did is episodic—breaks into episodes that can be eliminated without affecting the story. This, as Aristotle told us, is bad for business, and relegates those films to what we currently call art-house status. Only plot sells: not beautiful language, not beautiful shots, not beautiful stars; plot. Which is to say because, not and then. The king died and then the queen died, said W.H. Auden, is a story; the king died and then the queen died of grief is a plot.In his first solo-directed feature The White Sheik Fellini did give us a unified plot: provincial newlyweds come to Rome to meet his family and she gets lost and winds up with a photo-roman hero she's always adored, played by the superb Alberto Sordi. (Woody Allen took this for one of the strands of To Rome with Love, and has a Sordi look-alike for the star. So fond was Allen of the piece that, though it’s only a day-long thing, he edits it in with other strands that carry us through weeks, as if they were happening simultaneously.)

Apart from that one, in Fellini’s work, only 8 ½ is all of a piece.

Apart from that one, in Fellini’s work, only 8 ½ is all of a piece.Of course Guido’s Catholic upbringing has repressed him. Enter Freud. To clog the intelligence with an idea is un-Shakespearean, so here ends the resemblance to Hamlet, which may be construed as a systematic flushing of ideas. We enjoy them as we evacuate, but this is nothing to the postpartum levity; Hamlet, like Guido, feels lighter in act five. Ideas, to change the metaphor, or perhaps not, are fireworks displays, illuminating the terrain for a moment, existing for their own glory, then vanishing. (I like the Irish-accent pun in Finnegans Wake: “when they were jung and easily freudened.”)

Hamlet renounces all precedent, but Fellini is a classicist. The art historian Kenneth Clark said that one of the aspects of classicism is smoothness of transition. Few films are as smooth as 8 ½.

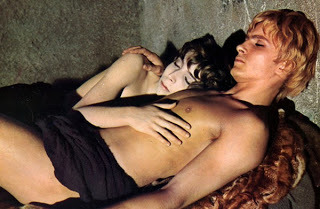

Classicism is Fellini's moral touchstone. At the end of La Dolce Vita Marcello and his cronies invade a friend’s beach house for an orgy, and when the owner returns he is amused, tolerant; but when they start breaking things he throws them out. He is a balanced man, a classical man, and we meet him again in Satyricon, the aristocrat who, now that everything is falling apart, frees his slaves, sends his children away to safety and commits suicide with his wife. Do with the house now what you want. Does Fellini approve of Marcello's orgy, of Encolpio's ambisexualism, of Casanova's exploits? Yes and no.

Dante inspires 8 ½ as Piranese, the ultimate designer of labyrinths, does City of Women, and the labyrinth is Fellini's image of human existence. In the castle maze of La Dolce Vita Marcello and Anouk Aimée make contact by voice through an acoustic whatsit and exchange words of love while she makes it with another guy. In Satyricon's Cretan-style labyrinth the murderous Minotaur turns out to be a joke. Like Icarus Guido wants to fly, Toby Dammit wants to fly, Snaporaz wants to fly.

Dante inspires 8 ½ as Piranese, the ultimate designer of labyrinths, does City of Women, and the labyrinth is Fellini's image of human existence. In the castle maze of La Dolce Vita Marcello and Anouk Aimée make contact by voice through an acoustic whatsit and exchange words of love while she makes it with another guy. In Satyricon's Cretan-style labyrinth the murderous Minotaur turns out to be a joke. Like Icarus Guido wants to fly, Toby Dammit wants to fly, Snaporaz wants to fly.People who argue that Shakespeare wasn't pornographic cannot have read “Venus and Adonis.” “Man delights not me; no, nor Woman neither; though by your smiling you seeme to say so.” Sounds like he's been there, though.

Fellini's sensuality is all-consuming, and in this he and his compagni are fixed entities. “Change!” says Snaporaz to the feminists; “Into what?” A journalist shouts to Guido, “Is pornography the most intense form of entertainment?” Sylva Koscina's performance as the sexy sister in Juliet of the Spirits removes, for the moment, doubt.

Hamlet by contrast is a master of change. The purity of total change is hypnotic in him, as long as it isn’t moral.

Hamlet by contrast is a master of change. The purity of total change is hypnotic in him, as long as it isn’t moral. What a pair of rapscallions!

Of course art is not moral. Morality is intention. In Roman Catholic sin-ology the intention makes or unmakes the sin. In art intention counts for nothing. You make a film, Jean Renoir said, to find out what it will look like. In Hollywood movies intention counts for everything.

The only other filmmaker we can compare to Fellini is Luis Bunuel, and both are Freud guys. For both it comes down to the sexual impulse. Which, sure. Both do fantasy and dream, and blur their borders with reality.

Bunuel is a great poet. In The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie a boy’s dead mother calls to him from the closet where her clothes sway. As a kid I never had such a strong sense of my mother’s presence as when I went to her closet, opened the door and smelt the perfume.

Bunuel made for me what is the ultimate horror film. Most people find The Phantom of Liberty funny. (This is the one where people sit on toilets at the dinner table, and escape to the bathroom to eat.) But he so accurately gets the entrapment of dreaming, which leads us by association from this to that in a way entirely beyond our control, that it frightens me.

Bunuel made for me what is the ultimate horror film. Most people find The Phantom of Liberty funny. (This is the one where people sit on toilets at the dinner table, and escape to the bathroom to eat.) But he so accurately gets the entrapment of dreaming, which leads us by association from this to that in a way entirely beyond our control, that it frightens me.But superb as he is, he is as cold as Velázquez. Fellini, as I don’t have to tell you, is warm warm warm. He mocks himself over his own nostalgia, but it’s no less compelling for that.

Guido is tender. Hamlet is sensitive, but he’s not tender. Falstaff is tender. Lear, at the end, is tender. Not Hamlet. (“Think yourself a baby That you have ta'en these tenders for true pay, Which are not sterling.”)

To Giulietta’s dismay Federico was active in the field of love, but he didn’t see himself as a man of action: “I am the only one I know,” he once said, “who can admit that it’s all fantasy.” The man of action he satirized in Casanova.

To his fantasies Fellini gave the classical form of goddess-worship. The labyrinth is where you don’t know what’s going on. As the Goddess tells Roberto Benigni’s holy fool in Fellini’s last film, The Voice of the Moon, he’s not supposed to know what’s going on. “You do not have to understand. Woe to him who understands,” she says, and she has the last word. I don't know if that would satisfy Hamlet, but he does, in the fifth act, seem at peace with the divinity who directs him.

To his fantasies Fellini gave the classical form of goddess-worship. The labyrinth is where you don’t know what’s going on. As the Goddess tells Roberto Benigni’s holy fool in Fellini’s last film, The Voice of the Moon, he’s not supposed to know what’s going on. “You do not have to understand. Woe to him who understands,” she says, and she has the last word. I don't know if that would satisfy Hamlet, but he does, in the fifth act, seem at peace with the divinity who directs him. The holy fool is a figure Fellini had cultivated in the Neo-Realist days, possibly because Giulietta—indomitable, wide-eyed with wonder—was so adept at playing it. Does Zampanò abuse her? All people have value, Il Matto tells her, one holy fool to another.