Hannah Fielding's Blog, page 92

December 19, 2014

A Christmas Feast by Katie Fforde

Christmas is a wonderful time of year, of course, but a busy one, and if you’re an avid reader like me, you can end up feeling a little bereft come the New Year: what happened to the time to yourself you dreamt of when you would curl up and get lost in a romance novel? This short-story collection is the perfect answer – offering quick-grab romance stories on a Christmas theme.

The author suggests in her foreword:

‘[T]he point of A Christmas Feast is that it’s full of little treats – stories you might have time to read while you’re waiting for the mince pies to brown or for the bath to run.’

Of course, I’ve devoured this ‘feast’ pre-Christmas, but I do think the book would lend itself well to offering a little escape here and there over the holiday season. The style is easy to read, and the stories easy to dip in and out of. Some are longer; some are like a magazine story.

I really like the feel of the writing: it’s not frivolous and silly, but warm and witty with the odd touch of poignancy. The stories just the right picks for the season. I especially enjoyed one that is centred on two strangers getting snowed in together in the wilds of Scotland. There’s quite a cast of characters through the collection, but I liked them all. I was intrigued by the professions the author incorporates – the publisher’s PR girl trying to handle a difficult author; the charity-shop worker dealing with what on first glance seems to be a very grumpy man; the newspaper reporter working undercover in a hotel kitchen. My absolute favourite story involves a rather uptight woman learning from a passionate Italian man how one should really eat – cue mouth-watering descriptions!

For me, the most wonderful part of the book is the theming. The stories have been pulled together to offer a Christmas feast to the reader, and so they are organised as courses:

Champagne and canapés

Starter

Main course

Dessert

Coffee and chocolate truffles

That alone feels delightfully indulgent.

A lovely book to pick up as a gift for a female friend or relative this Christmas – or, better yet, a gift to yourself. Think of it as your sanity saver for the holidays!

A Christmas Feast is available now from Amazon; click on the book cover below to visit the store.

December 17, 2014

The Great British post box, as beloved by Charles Dickens

I have finally finished writing my Christmas cards; each year it seems to take a little longer. I very much enjoy the whole process: selecting cards, handwriting messages, stuffing and addressing envelopes, attaching stamps. But the best part is walking to the village post box, a long-standing cherry-red pillar, and posting in each card. I love the satisfying noise each makes as it falls onto the pile within!

I have finally finished writing my Christmas cards; each year it seems to take a little longer. I very much enjoy the whole process: selecting cards, handwriting messages, stuffing and addressing envelopes, attaching stamps. But the best part is walking to the village post box, a long-standing cherry-red pillar, and posting in each card. I love the satisfying noise each makes as it falls onto the pile within!

The British post box has become, in its one-hundred-and-sixty-year history, an iconic symbol of Britain. It all began with a writer: Anthony Trollope. Back in the 1850s he worked for the Post Office and wrote a report recommending fixed pillar boxes be trialled in the Channel Islands. The trial was a success, and a year later London got its first boxes – and from there, they slowly sprang up around the country. They were painted green initially, so as not to be eyesores but blend with the landscape, but in the 1870s it was decided that they needed to be more visible, and a programme of painting began. So many post boxes existed by than that it took ten years to paint them all red.

Various designs have been employed over the years, from green to red, hexagonal to cylindrical, but most have in common that they are for public use. But how about having your own personal post box to fill with correspondence? Kent-based writer Charles Dickens managed to secure just that for himself.

It is a well-known fact that Dickens was a prolific writer. As well as editing a weekly journal and lecturing and performing around the country, he wrote fifteen novels, five novellas and hundreds of articles and short stories. But what of letters, the chief means of communication in the days before the telephone and digital technology? According to Marion, Dickens’s great-great-granddaughter, he wrote more than 14,000 letters. That necessitates a great many trips to the post box – but from his home, Gad’s Hill Place, it was a mile’s walk to the nearest box in the village of Higham. What was a man to do? Petition for a new post box outside his home, of course! He wrote in a letter on 29 March 1859:

I think that no one seeing the place can well doubt that my house at Gad’s Hill is the place for the letter-box. The wall is accessible by all sorts and conditions of men, on the bold high road, and the house altogether is the great landmark of the whole neighbourhood.

Once the post box was duly erected, it seemed the service was very personal indeed – Dickens would leave the poor postman waiting while he finished his latest piece of mail. ‘The postman is waiting at the gate to tramp through the snow to Rochester and is unlawfully drinking a glass of gin while I write this,’he wrote to his friend Charles Kent.

Dickens’s post box remained in place until the 1990s, when it was decommissioned, but this month it was officially reopened. I read in the newspaper that any cards or letters posted in the box before Christmas will be franked by Royal Mail with a special ‘CD’ postmark, like the seal Dickens used on his letters. I rather wish now that I had known about that before posting my cards. But then it is a long way from my home near Deal in Kent to Gad’s Hill, and based on this story I doubt Dickens would have approved of my travelling more than a very short walk to post my mail.

December 15, 2014

Lost love letters: the next 50 Shades?

What’s hot in publishing right now? A book called The Passion of Mademoiselle S. The rights to the book have been snapped up by major publishers in the UK, the US, Australia, New Zealand, France, Italy, Holland and Brazil. Mademoiselle Simone, author and protagonist of the non-fiction work,must be delighted, you may think, at all this excitement and literary glory to come. Perhaps she is, someplace – but not on this earth.

What’s hot in publishing right now? A book called The Passion of Mademoiselle S. The rights to the book have been snapped up by major publishers in the UK, the US, Australia, New Zealand, France, Italy, Holland and Brazil. Mademoiselle Simone, author and protagonist of the non-fiction work,must be delighted, you may think, at all this excitement and literary glory to come. Perhaps she is, someplace – but not on this earth.

The truth is, nobody knows who exactly Mademoiselle Simone was; past tense, because the letters she wrote that comprise the book spanned the period of 1928 to 1930. But the work is being heralded as ‘an epistolary erotic treasure: a chronicle of the extreme passion of a well to do young lady in 1920s Paris’.

The agent for the work describes it thus:

While helping a friend clean out an old apartment, French ambassador Jean-Yves Berthault discovers a hidden leather pouch filled with handwritten letters. Upon reading the first one, he realizes that an extraordinary adventure lies at his fingertips.

Penned by the mysterious Simone in the 1920s, the letters tell the story of her passion for a younger married man, Charles. The reader is immediately drawn into this riveting tale of sexual awakening as Simone finds herself immersed in a world of physical pleasure hitherto unknown to her. Gradually, Simone loses touch with reality and becomes obsessed with Charles. Yet the more desperately she wants him, the less he returns her affection.

As her hunger for Charles grows, Simone forces him beyond his sexual boundaries, ultimately reversing their roles. Simone wants Charles to taste unsuspecting pleasures and she turns him into her “mistress.” With each taboo they break, he gives himself further to her—until their last fateful sexual encounter.

The Passion of Mademoiselle S. forms an erotic tour de force in its unbridled lust, intimacy, and abandonment. In language that is by turns elegant, moving, and crude, Simone’s striking love letters reveal an all-encompassing appetite for a man who evades her. A journey of sexual and psychological exploration, The Passion of Mademoiselle S. shows the life of a woman in the 1920s who, though bound by her class and gender, is able to transcend that confinement and embrace her true self.

A powerful synopsis indeed that would sit well on any work of fiction, let alone a collection of actual letters. The UK editor who bought the book for William Heinemann told The Bookseller that it ‘is a time capsule of a book’ and ‘the fact that it was such a deeply buried secret for all these years makes it particularly special’. I understand the interest in something long-buried; the knowledge and feel of the past it creates. It’s an important work, from that angle.

But I can’t help wondering about the ‘deeply buried secret’ element. The love letters were discovered in a cellar, where ‘they appeared to be deliberately hidden under several crates of empty jars’ (source). Deeply buried. Deliberate. Did Simone, whoever she was, wish them to remain thus?

One could argue that if she never wanted those letters to be read by others, she’d have destroyed them – burnt them as have countless writers in history. But perhaps she could not bear to; they were her heart and soul laid out on paper. Perhaps she left the letters there and intended to come back for them someday, but was unable to. Perhaps the idea of seeing them in print would have been terrible for her. Or perhaps, after all, she’d have been honoured and thrilled. We cannot know.

The publication raises interesting questions. When you create something within the sphere of the arts, when does that creation shift from being personal to public property? Upon your death? When no immediate relatives remain to be affected by the publication? What about profit? Should this book be the next big thing in the erotic genre, who will make the fortune? Should the ‘characters’ in the book be identified, and their relatives awarded royalties?

One lesson from the story is clear: if you create something – a poem, a painting, a wonky vase – that you never want to see the light of day, you must either destroy it or bury it very, very deep indeed.

December 13, 2014

Head to the cinema for the ultimate Christmas film: It’s a Wonderful Life

If you only watch one movie this Christmas, make it this one. That’s what respondents of a recent poll of more than 2,000 British people think: they heralded It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) as the best Christmas film ever made. I can see why – if there’s ever a film to restore your faith in humanity, this is it.

If you only watch one movie this Christmas, make it this one. That’s what respondents of a recent poll of more than 2,000 British people think: they heralded It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) as the best Christmas film ever made. I can see why – if there’s ever a film to restore your faith in humanity, this is it.

In case you’re not familiar with the story, here’s a summary:

The film stars James Stewart as George Bailey, a man who has given up his dreams in order to help others and whose imminent suicide on Christmas Eve brings about the intervention of his guardian angel, Clarence Odbody (Henry Travers). Clarence shows George all the lives he has touched and how different life in his community of Bedford Falls would be had he never been born.[Source]

A movie about a man thinking of suicide may sound depressing, but in fact it’s anything but. Here are seven reasons to watch the movie:

1. It was directed by Frank Capra, the acclaimed director, producer and writer who worked his way up from the ghetto to Hollywood, becoming one of the most influential directors in Hollywood in the 1930s. His approach of improvising rather than scripting scenes carefully has left a legacy of powerful cinema.

2. It’s one of the most critically acclaimed films in history, and is commonly high in ‘Best Ever Movie’ lists, including those of the American and British Film Institutes.

3. The cast is headed up by screen legend James Stewart – handsome, charismatic and indisputably believable in all his roles.

4. The film has taken on a life of its own, capturing the public imagination so that it went from box-office flop to essential viewing at Christmas over a period of thirty years. Capra told the told the Wall Street Journal: ‘I’m like a parent whose kid grows up to be president. I’m proud… but it’s the kid who did the work.’

5. Christmas is all about nostalgia, and this black-and-white classic beautifully stirs such a mood. Colorised versions of the film have been released, but nothing can beat the beauty of the original tones.

6. It has such warm, witty dialogue as this:

George Bailey: Mary Hatch, why in the world did you ever marry a guy like me?

Mary: To keep from being an old maid!

George Bailey: You could have married Sam Wainright, or anybody else in town…

Mary: I didn’t want to marry anybody else in town. I want my baby to look like you.

George Bailey: You didn’t even have a honeymoon. I promised you…

[stops]

George Bailey: Your what?

Mary: My baby!

George Bailey: [stuttering] Your, your, your, ba- Mary, you on the nest?

Mary: George Baily Lassos Stork!

George Bailey: [still stuttering] Lassos a stork?

[Mary nods]

George Bailey: What’re’ya… You mean you’re… What is it, a boy or a girl?

Mary: [nods enthusiasticly] Mmmm-hmmm!

7. As expressed by David Wilson in the Guardian: ‘I watch It’s A Wonderful Life every year because [its] message needs to be repeated – time after time – and certainly just as often as Come All Ye Faithful, for it is that message that reminds us to do what we can to make this world a better place.’

No doubt the film will be on the television schedule this year, but as with all films the emotional impact is heightened by watching on the big screen. To markIt’s A Wonderful Lifeas the ultimate Christmas film, Odeon Cinemas are holding screenings at 80 of their UK cinemas on 15 December. The perfect outing to get you in the holiday spirit!

December 10, 2014

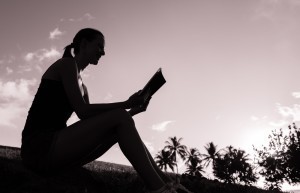

Writing for your target reader: yourself

Here is a golden rule of writing: Always write with the reader in mind. It means you should know exactly who your target reader is, and write for them.

Here is a golden rule of writing: Always write with the reader in mind. It means you should know exactly who your target reader is, and write for them.

Rebecca Woodhead made a superb case for this in her article ‘Social Studies’ in the January edition of Writing Magazine (I’ve never quite understood why on the first of each month one receives magazines dated with the following month!). She suggests that you picture your ideal reader in vivid detail – what they look like, how they respond to your book, what makes them tick. Most importantly, she advocates connecting emotionally with that target reader (she uses the term ‘avatar’). So you imagine that your writing moves this person, empowers them, inspires them. Then, you ‘serve them’. She explains: ‘You are no longer the most important person in your vision; your readers are.’

Rebecca writes chiefly about author marketing, and this is a very insightful look at how an author may connect better with readers. I very much like the idea of not ‘selling’ to readers, but serving them. Nothing makes my day brighter than reading a review of one of my books in which it’s apparent that my writing has touched the reader. I’ve facilitated escapism; I’ve enabled a rosy glow – I’ve helped someone to dream a little.

I decided to sit down, as suggested in the article, and get to know my ideal reader by creating her as a character. I wrote lots of notes; among them:

Likes to travel and have new experiences

Appreciates good company

Enjoys the arts, especially those related to storytelling

Is deeply affected by emotion

Defines herself as a romantic

Is a daydreamer

Believes in fate and true love

I spent a very enjoyable hour fleshing out the character as I do for those in my books, thinking about how she feels and thinks and acts. Then I made a coffee and looked over my notes. The first thought that struck me when I looked at the big picture was, ‘I think this reader and I would get along well.’ The second thought, ‘Oh. I am this reader!’

I had essentially created a character sketch of myself. In some ways, that’s because I’m the quintessential romance novel reader. But beyond that, I think the sketch tells a fundamental truth: I write for myself. I have always believed in writing the kind of book I’d like to read, rather than trying to chase a trend in romance fiction or writing a book that’s formulaic. A book can only impassion a reader, as I want my novels to do, when the writer was impassioned while writing – and that is possible only when you write for yourself. Allen Ginsberg said, ‘To gain your own voice, you have to forget about having it heard.’ That is guidance I took to heart in the years I wrote without seeking publication – an audience for my works. I spent many years learning about the craft and finding my own voice, so that now the words flow without obstruction.

Perhaps, then, marketing should be refocused with, at its core, the truth that the ideal reader of any book is the author him- or herself. Then, sharing the story becomes a journey in connecting to likeminded people in the world. That, for many writers, may be a journey indeed; a recent Mslexia survey (Dec/Jan/Feb issue) revealed that the notion of the writer as a hermit is not without basis. But for me, discovering readers who enjoy my writing is a wonderful part of the process. I am happiest, it is true, when writing alone beneath a tree in my garden or at my desk by the log fire, lost in a world of passion; but I am veryhappy when I connect to a reader who appreciates my take on the world. Writer William Nicholson says it best: ‘We read to know we’re not alone.’ And we write for the same reason.

December 8, 2014

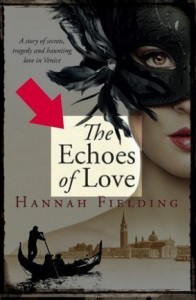

The thinking behind book titles

The cover of a book must be beautiful, the blurb must be compelling, the first page must pull the reader in and make him or her want more – but above all, the title must be perfect. In no more than a few words the author must:

The cover of a book must be beautiful, the blurb must be compelling, the first page must pull the reader in and make him or her want more – but above all, the title must be perfect. In no more than a few words the author must:

Showcase his or her writing style.

Encapsulate the mood of the book.

Convey the main theme of the story.

For some authors the title is the hardest thing to write, taking longer to shape than an entire chapter; for others the ideas come thick and fast. Often a manuscript has a working title, but it changes several times before publication. Other authors start out with a title in mind, and stay loyal to that throughout. (Unless the publisher insists on changing it, which is fairly common.)

The reason for all the difficulty is that different styles for titles exist, and determining which to use for a book is not always straightforward. So far in my novels I’ve used three different approaches for the title.

The title that ties into a scene

Inspiration for my debut novelcame from many sources. Much of the story was in my mind: I daydreamed and researched and plotted and planned, and finally I was ready to write. All that was missing to pull the threads together was a title. Then, one evening, my family and I were sitting around a campfire in the garden, and I was gazing at the incandescent embers. The fire was smouldering quietly, giving out a strong glow, just like the passions locked within Coral and Rafe. Embers that could ignite into fire, but also, if untended, die out. The title Burning Embers was born.

Inspiration for my debut novelcame from many sources. Much of the story was in my mind: I daydreamed and researched and plotted and planned, and finally I was ready to write. All that was missing to pull the threads together was a title. Then, one evening, my family and I were sitting around a campfire in the garden, and I was gazing at the incandescent embers. The fire was smouldering quietly, giving out a strong glow, just like the passions locked within Coral and Rafe. Embers that could ignite into fire, but also, if untended, die out. The title Burning Embers was born.

Heat permeates the novel, through the backdrop of Kenya and the attraction between the protagonists, so that the notion of burning embers resonates throughout. But I decided to write the phrase into the book as well, because I wanted to really tie together the burning embers to Coral and Rafe:

Though the afternoon sunshine was beginning to fade, the air was still hot and heavy. Coral was struck by the awesome silence that surrounded them. Not a bird in sight, no shuffle in the undergrowth, even the insects were elusive. They climbed a little way up the escarpment over the plateau and found a spot that dominated the view of the whole glade. Rafe spread out the blanket under an acacia tree. … They chatted casually, like old friends, about unimportant mundane things, as though they were both trying to ward off the real issue, to stifle the burning embers that were smoldering dangerously in both their minds and their bodies.

The title that draws on a literary quotation

Quoting from literature is a long-standing tradition for authors. Here are some examples:

Quoting from literature is a long-standing tradition for authors. Here are some examples:

A Passage to India: a quote from Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman

As I Lay Dying: a quote from The Odyssey by Homer

For Whom the Bell Tolls: a quote from Meditation XVII by John Donne

From Here to Eternity: a quote from Gentlemen-Rankers by Rudyard Kipling

His Dark Materials: a quote from Paradise Lost by John Milton

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings: a quote from Sympathy by Paul Laurence Dunbar

No Country for Old Men: a quote from Sailing to Byzantium by William Butler Yeats

Of Mice and Men: a quote fromTo a Mouse by Robert Burns

Tender Is the Night: a quote from Ode to a Nightingale by John Keats

Vanity Fair: a quote from The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan

Where Angels Fear to Tread: a quote from Essay on Criticism by Alexander Pope

Regular readers of my blog will know I love quotations, and so it is natural for me to take inspiration from my readings of literature. For The Echoes of Love, I drew on two quotes that were in my mind as I wrote the book:

‘Footfalls echo in our memory/Down the passage which we did not take…’T.S. Eliot

‘Multitudinous echoes awoke and died in the distance . . . And, when the echoes had ceased, like a sense of pain was the silence.’ – Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

These quotes form the epigraph to the book, to further cement the meaning of the title.

The single-word title

There’s a powerful simplicity in selecting only one word to stand as a title. It’s brave, it’s bold –it says, ‘Here’s what this book is all about.’

Some one-word titles push forth the central character, like Emma and Carrie. Others convey the theme, like Persuasion and Atonement. There are those carefully chosen to intrigue, like It and Holes and Room. And those that don’t have a great deal to do with the plot of the book but create a mood, like Twilight.

For my forthcoming novel, my publisher encouraged me to consider a one-word title, and I was keen to give this a try, because I think the style will tally well with the fiery spirit in the book. After some brainstorming I settled on…

… well, watch this space for the cover reveal for my new novel, coming very soon!

December 5, 2014

The Prince Who Loved Me by Karen Hawkins

From the blurb:

Prince Alexsey Romanovin enjoys his carefree life, flirting—and more—with every lovely lady who crosses his path. But when the interfering Duchess Natasha decides it’s time for her grandson to wed, Alexsey finds himself in Scotland, determined to foil her plans. Brainy, bookish, and bespectacled, Bronwyn Murdoch seems the perfect answer—she isn’t at all to the Duchess’s taste.

Living at the beck and call of her ambitious stepmother and social butterfly stepsisters, Bronwyn has little time for a handsome flirt—no matter how intoxicating his kisses are. After all, no spoiled, arrogant prince would be seriously interested in a firm-minded female like herself. So…wouldn’t it be fun to turn his “game” upside down and prove that an ordinary woman can bring a prince to his knees…

An absolute delight to read – this book gave me a week’s worth of bedtime reading that left me falling asleep with a smile on my face.

The storyline draws from the Cinderella trope in a fun way, but isn’t weighed down by an attempt to faithfully retell the classic fairytale. For a standalone novel, the book has just the right amount of story, I think – plenty of action, but not so much that the author does not make space for great character development.

Alexsey makes for a wonderful prince. I love his self-confidence, his belief that he can just get what he wants when it comes to power and women, and also his humour and affection for his family and friends (and, ultimately, Bronwyn) which soften his character. Bronwyn is a brilliant heroine: smart, independent and strong, the kind of woman who’s undeterred by being locked in a room and simply climbs out of a window and down a tree. The secondary characters are also colourful and likeable; I especially enjoyed a second love story interwoven in the plot, and the machinations of Bronwyn’s prickly-but-not evil stepmother and Alexsey’s gypsy grandmother, Natasha.

The writing style is wonderful: witty and warm, and so easy to read. My favourite element of the book is the author’s incorporation of quotes from another (fictional) book, The Black Duke – a melodramatic romance novel that Bronwyn is reading. Cleverly, the author juxtaposes the story of The Black Dukewith that of The Prince Who Loved Me, which makes for a sometimes funny, sometimes poignant comparison. In doing so she helps the reader who is reading this romance novel to connect to Bronwyn, who is also reading a romance novel. The layering of the stories is fun, original and clever, and made this book really stand out to me as a treasure in the genre.

I eagerly await the next book in the Oxenburg Princes series.

The Prince Who Love Me is available now from Amazon; click on the book cover below to visit the store.

December 3, 2014

The hunger for the untold story

Type ‘untold story’ into an Amazon and the search engine returns more than 8,000 results. The phrase is frequently coupled with a title to create a marketing hook: ‘Read this book and you’ll get another angle on the story.’ Marketers know that the ‘untold story’ subtitle sells books, and so they apply them to books.With true stories, the results are mixed: sometimes you get an important new slant on affairs; sometimes the untold story is merely gossip and exploitation. But occasionally, an author explores an untold story in fiction – and that can result in an exceptional story indeed.

To consider how we, as the audience, engage with the untold story, consider two very innovative retellings of popular stories: Wicked and Pan.

Wicked

In Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West (1995) author Gregory Maguire used the classic L. Frank Baum novel of 1900, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, and its sequels, to explore political, social and ethical facets of the nature of good and evil. The book sparked imagination of lyricist and composer Stephen Lawrence Schwartz, who brought the story to the musical theatre stage, and since them millions of people worldwide have experienced an entirely different take on the well-known story. Through the retelling, you see the witches of Oz in an entirely new light. Two unlikely friends, Elphaba and Glinda, fall in love with the same man. The rivalry that ensues and their differing take on the Wizard’s corruption see their friendship disintegrate and the two stand at polar opposites: Glinda as ‘the Good’ and Elphaba as ‘the Wicked Witch of the West’. But as the story shows, Glinda isn’t as good as her name suggests, and as for Elphaba – well, there are powerful, moving reasons for all she does. The context of the story makes it impossible to ever watch the original film or read the original books again and interpret her as you once did – as purely, one-dimensionally wicked.

Pan

There have been several movie based on the classic book PeterPan. An early 1990s one, Hook, had fun playing with the archetypal roles of Peter and Hook. But a new film, Pan, set to release in 2015, is delving deeper to tell the untold story of the two characters, and how they came to be sworn enemies. Judging by the trailer, like Glinda and Elphaba, there was once more than enmity between this pair.

The draw

So what is it that entices us to engage with a retelling? I think it’s several factors:

We love to solve puzzles. Authors leave plenty of unanswered questions in their books – because that’s good fiction! You follow the golden rule of writing to include only that information that is essential for developing the story and the main characters. So many little facts are unwritten; especially about minor characters.

We love to be surprised by clever twists. When I first saw Wicked, I clapped heartily at the curtain call – not just for the cast and the orchestra, but for the writers. How clever! I kept thinking. The twists delighted me.

We love to find the good in the evil.It’s natural to want to find the best in people, and caricatures of pure evil like Captain Hook and the Wicked Witch of the West are unsettling. The untold story helps you separate the act from the person – a character may do evil things, but the reason for his or her action is what’s really important. The extra dimension humanises the demon. In reading or watching the untold story, we find realism in the fiction.

The untold story fascinates me, especially when I’m writing my own fiction. There are always characters that I wish I could explore more. Morgana, the exotic dancer in Burning Embers, is a good example – she’s ‘the other woman’, but I know she’s so much more than that!

What do you think? Do you enjoy new versions of stories? New perspectives and angles? To see a character subverted?

December 1, 2014

Annotating the first edition

Have you heard about the ‘First Editions: Redrawn’ auction? It will take place at Sotheby’s in December and will raise funds for the charity House of Illustration, which runs an educational and heritage centre in London. What’s very special about this auction is the lots: 38 editions of classic children’s book, each re-illustrated and annotated. As House of Illustration explains: ‘Thirty-four acclaimed illustrators – and some authors – have returned to one of their classic books, adding extra illustrations, comments on existing drawings and personal insights about the motivation behind characters.’

Have you heard about the ‘First Editions: Redrawn’ auction? It will take place at Sotheby’s in December and will raise funds for the charity House of Illustration, which runs an educational and heritage centre in London. What’s very special about this auction is the lots: 38 editions of classic children’s book, each re-illustrated and annotated. As House of Illustration explains: ‘Thirty-four acclaimed illustrators – and some authors – have returned to one of their classic books, adding extra illustrations, comments on existing drawings and personal insights about the motivation behind characters.’

The books up for auction include:

Lost and Found, in which Oliver Jeffers notes that his book was inspired by the true story of a little boy who stole a penguin from Belfast Zoo.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, in which Quentin Blake draws a brand-new sketch of Charlie eating a chunk of vanilla fudge.

The Snowman, in which Raymond Briggs confesses he was never too happy with the rendering of the melted snowman.

Paddington, in which Michael Bond explains the inspiration for the story, dating back to memories of evacuees during the war.

The chance to get a peek into the mind of the artist is rare – and wonderful. Take The Snowman, for example, a classic of children’s literature first published in 1978. But how does the creator feel it sits in the modern era? He writes in his annotated edition:‘Blue and white striped pyjamas! Pre-historic, I’m told. For me, pyjamas have to be blue and white stripes otherwise they are not pyjamas.’ And: ‘Dressing gown! Pre-historic again? Youngsters now wear ONESIES, whatever they are.’

The concept is a wonderful one, don’t you think? A little like the extra you find on a DVD movie these days that offers a cut of the film with commentary from the cast and director. I wonder: should this be the norm, rather than a rarity? Should an author create a special print copy of his or her book, and then jot notes in the margin?

In my novels The Echoes of Love and Burning Embers, for example, there is so much I could share about how I feel about a plot element or a character; why I made certain choices in the writing; and of course the many inspirations for the books. I could slip in an anecdote of my times in Kenya and Italy. I could note down a recipe for a meal the characters are sharing. I could explain the background of a historical landmark, or share a legend associated with the story. I suspect, in fact, that my annotated edition would have to be printed with very wide margins to fit all I’d love to include!

What do you think of annotated editions? Do you think they enrich the reading experience? Reward the most loyal readers? Inspire, perhaps, others to write also? I would love to hear your thoughts.

The ‘First Editions: Redrawn’ auction will take place at Sotheby’s, New Bond Street, London, on 8th December at 7.30pm. You can bid in person, in advance of the auction or via the phone. For details, visit www.houseofillustration.org.uk . The full catalogue is available at www.houseofillustration.org.uk/media/_file/l14910-singlepgs.pdf.

November 28, 2014

Preserving the residences of literary greats

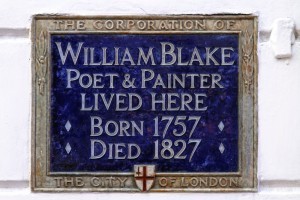

The blue plaque scheme in the UK is one of my favourite historical initiatives. It began in London, launched in 1867 by the Royal Society of Arts, as a means of connecting sites with people of historical interest. The first plaque was unveiled at 24 Holles Street, Cavendish Square, the birthplace of Lord Byron. Since then, some 900 plaques have been established in London alone – and plenty more in the wider country – to mark the places that mattered to all kinds of people: from statesmen to soldiers, architects to inventors. But the ones that have always most captured my imagination are those relating to people in the arts. To stand before a house in which an admired author wrote is moving. You realise that the person who in your mind has become legendary was once a real person, once stood right here. The connection is powerful. Inspirational.

The blue plaque scheme in the UK is one of my favourite historical initiatives. It began in London, launched in 1867 by the Royal Society of Arts, as a means of connecting sites with people of historical interest. The first plaque was unveiled at 24 Holles Street, Cavendish Square, the birthplace of Lord Byron. Since then, some 900 plaques have been established in London alone – and plenty more in the wider country – to mark the places that mattered to all kinds of people: from statesmen to soldiers, architects to inventors. But the ones that have always most captured my imagination are those relating to people in the arts. To stand before a house in which an admired author wrote is moving. You realise that the person who in your mind has become legendary was once a real person, once stood right here. The connection is powerful. Inspirational.

When it comes to literary heritage, a precedent has been set for not only marking the residences of writers but preserving them too. Many are looked after by the National Trust, and open to the public: you can visit, for example, Beatrice Potter’s 17th-century farmhouse, Hill Top, and Agatha Christie’s holiday place with a view, Greenway. Other homes have been made into museums: Jane Austen’s, for instance, and Wordsworth’s.

Now, The Blake Society is calling for donations to help it save the home of William Blake. A little cottage on the Sussex coast in Felpham, it is a place of huge historical import.It’s where the write penned the seminal poem ‘Jerusalem’, which became the lyrics for the English hymn so loved it’s a permanent and proud element of the programme at every Last Night of the Proms at the Royal Albert Hall:

The Blake Society wants to buy the cottage and preserve it as a place of inspiration for writers and ‘anyone who shares with Blake a belief that imagination is Britain’s gift and duty to the world’. But the price tag is £520,000, and the charity has to raise all that money by the end of today! In the UK, you can support the cause by texting FEET11 followed by a number from 1 to 9 (which will determine how much money is taken, from £1–9) to 70070.

What struck me most about The Blake Society’s plea for support this week were these words in a statement from Tim Heath, chair of society: ‘Blake is unusual in our culture in that he’s everywhere and nowhere – he’s had great lasting influence but has no home here.’ We have a duty, surely, to commemorate those who contributed to our modern lives, through all aspects. I’d love to see more plaques. I’d love to imagine a future in which one can walk around a town or city for an hour, looking up at buildings and learning, and feeling connected to the late and great.