Hannah Fielding's Blog, page 156

May 31, 2012

Port des Issambres – a view for writers

What do you think of the view? This is a beautiful port near my home in France. I sometimes take a thermos of coffee and a baguette of ham and cheese and spend the day writing there.

Excitingly, this is my first blog hop. The hop is hosted here: http://omnificpublishing.blogspot.co.uk/. Enjoy!

Port des Issambres

A beautiful port near my home in France. I sometimes take a thermos of coffee and a baguette of ham and cheese and spend the day writing there.

May 29, 2012

The creatures of African legends

When I was a teenager my family had a friend called Mr Chiumbo Wangai who was from Kenya. He would tell us all about his homeland – the landscapes, the people, the cultures. But my favourite tales were those he related based on African legends. And when I came to research my novel Burning Embers, it was wonderful to revisit those allegorical stories.

Running through Burning Embers is an undercurrent of folklore and native culture – embodied particularly in Coral’s old nanny, Aluna, who is superstitious and continually talks in riddles and proverbs. Rafe is similarly aware of the local stories, and he relates the legend of the curious monkey to Coral to explain why she should let sleeping dogs lie.

In all the books I read about African legends, it was clear that animals are the symbols for the lessons imparted – and there are such fun and inventive ways to explain the way the world works! Here are a few common legends in brief:

Why dogs chase: The monkey awoke the sleeping dog, and enraged it so much that it was then destined to chase any creature that looked at it. The lesson: let sleeping dogs lie.

How the zebra got his stripes, and the baboon a bare behind: The baboon and the zebra fought over who would drink from a watering hole. The zebra kicked the baboon up among the rocks, and he landed with a smack that tore off the fur on his behind. The zebra staggered through the baboon’s fire, scorching black stripes on his white fur. The lesson: don’t fight!

How the leopard got his spots: The hyena played a prank on the tortoise and put him high up in a tree. The leopard saw him there and carried him down. In gratitude, the tortoise asked the leopard to let him make the big cat beautiful. He agreed, and so the tortoise painted on his spots. The lesson: friends do nice things for each other.

Why hippos don’t each fish: The hippopotamus first grazed in forests and plains. But he was greedy, and he grew fatter and fatter. The fatter he got, the more the heat bothered him. He would go to the river to drink and look at the fishes swimming there, wishing he could live like them in the water. But his god, N’gai, forbade it because he did not want the hippo to eat all the fish. So the hippo offered N’gai a deal: he would lie in the cool water by day, and forage on the land for food by night. The lesson: there is always a compromise.

Why ostriches have long necks: The ostrich’s wife was flighty, and while he minded the nest, the ostrich would stretch his neck out and peer out to see his wife flirting with the other birds. He did it so often, his neck remained stretched. The lesson: you pay a price for being nosy.

Perhaps someday I shall rewrite the essence of Burning Embers as a children’s story, using anthropomorphism to convey the lessons learnt by the characters. Rafe would be the lion; Coral the gazelle (shades of Twilight’s ‘and so the lion fell in love with the lamb’). Morgana, a leopard, perhaps; and Cybil, a hyena. Then Dale, a lumbering elephant I think. And Aluna, a nosy ostrich. What do you think?

May 28, 2012

Chasing waterfalls

There is something so romantic about a waterfall. The roaring of the water in your ears; the rainbow of colours reflected in the downpour; the shock of the plummet from the horizontal river; the sense of nature’s might.

Little wonder, then, that those who dream up love stories are drawn to waterfalls to provide the backdrop for passionate, tumultuous, powerful scenes between lovers. I’m thinking, of course, of films like Cocktail and Breaking Dawn (with Darcy’s emergence from the lake shimmering at the end of my imagination) and all manner of romance novels.

In Burning Embers, I could not resist taking Coral and Rafe to a waterfall – to their own private clearing in the wild lands around Narok, Kenya.

There, in the middle of the depression, entirely enclosed by flowering shrubs, lay a phosphorescent expanse of water, shimmering like a sheet of silk in the rays of the midday sun. High above, a solid mass of white foam thundered from a narrow gulley; it leaped down, rolling over part of a sheer wall of mountain that stood like an impassive sentinel, its head in the clouds.

Rafe suggests a swim in the pond, but Coral is shy. Later, though, the lovers will meet here once more, and the beautiful surroundings will create the ambiance required for them to shed their inhibitions.

With waterfalls on my mind, I recalled a poem I love by Thomas Hardy – usually a rather depressing writer, I find, but in this case he encapsulates wonderfully the romance of the waterfall.

Under the Waterfall

‘Whenever I plunge my arm, like this,

In a basin of water, I never miss

The sweet sharp sense of a fugitive day

Fetched back from its thickening shroud of gray.

Hence the only prime

And real love-rhyme

That I know by heart,

And that leaves no smart,

Is the purl of a little valley fall

About three spans wide and two spans tall

Over a table of solid rock,

And into a scoop of the self-same block;

The purl of a runlet that never ceases

In stir of kingdoms, in wars, in peaces;

With a hollow boiling voice it speaks

And has spoken since hills were turfless peaks.’

‘And why gives this the only prime

Idea to you of a real love-rhyme?

And why does plunging your arm in a bowl

Full of spring water, bring throbs to your soul?’

‘Well, under the fall, in a crease of the stone,

Though precisely where none ever has known,

Jammed darkly, nothing to show how prized,

And by now with its smoothness opalized,

Is a grinking glass:

For, down that pass

My lover and I

Walked under a sky

Of blue with a leaf-wove awning of green,

In the burn of August, to paint the scene,

And we placed our basket of fruit and wine

By the runlet’s rim, where we sat to dine;

And when we had drunk from the glass together,

Arched by the oak-copse from the weather,

I held the vessel to rinse in the fall,

Where it slipped, and it sank, and was past recall,

Though we stooped and plumbed the little abyss

With long bared arms. There the glass still is.

And, as said, if I thrust my arm below

Cold water in a basin or bowl, a throe

From the past awakens a sense of that time,

And the glass we used, and the cascade’s rhyme.

The basin seems the pool, and its edge

The hard smooth face of the brook-side ledge,

And the leafy pattern of china-ware

The hanging plants that were bathing there.

‘By night, by day, when it shines or lours,

There lies intact that chalice of ours,

And its presence adds to the rhyme of love

Persistently sung by the fall above.

No lip has touched it since his and mine

In turns therefrom sipped lovers’ wine.’

May 25, 2012

Recipe: Bouillabaisse

Have you tried bouillabaisse? It’s one of my favourite dishes because it’s a specialty of the region where I live in France, and because it calls to mind my childhood. Growing up, my parents would throw big parties for relatives and friends at our home, and my father would cook for the occasion his best dish: bouillabaisse. How I looked forward to dinner time, for my father’s recipe was out of this world – all these years later, as I write I can almost taste it. I made a game of it once I was an adult, choosing bouillabaisse on the menu in restaurants and seeing how effectively it cast me back to childhood. No dish yet has quite lived up to that memory, not even my own, although a restaurant near my home in France has come close.

Bouillabaisse originates from Marseilles, and it is essentially a stew comprising five or six types of fish, vegetables like leeks, onions, tomatoes, celery and potatoes, and Provençal herbs and spices. Each chef – even the best in France – has a different take on the dish, which I think accounts for its popularity. Some use potatoes; some do not. Some add the fish to the broth; some serve them on the side. Most serve the dish with a rouille, which is a kind of mayonnaise with garlic, saffron and cayenne pepper, spread on grilled slices of local bread which may be served on the side, or dropped into the stew.

The types of fish added to the bouillabaisse vary depending on those available to the chef, and the chef’s personal choice. You may find scorpionfish, conger, beam, monkfish, turbot, octopus, mussels and crabs. Having grown up living by the Mediterranean, I have always loved fish – and this dish incorporates so many types that I find the blend of flavours quite delicious.

With so many ingredients, making bouillabaisse at home is a lengthy and involved process. I’ve developed a simple cheats’ recipe you can try to get a simple flavour of the dish. I do hope you enjoy it.

Ingredients

2 tablespoons olive oil

2 cloves garlic, crushed

1 large onion, peeled and sliced

1 leek, thinly sliced

1 can plum tomatoes

2 teaspoons of herbs de Provence

6 cups fish stock (fresh or made up)

Your preferred fish – most supermarkets do a ‘fish pie’ mix, or choose three types of fish like cod, halibut or snapper and some prawns and mussels

1. Fry the garlic, onion and celery in the oil until brown.

2. Add the tomatoes, herbs and stock and bring to the boil.

3. Simmer until the liquid reduces (about 15 minutes).

4. Reduce the heat and add the fish. Cook for 2 minutes.

5. Add any mussels and prawns and simmer until the shells open and the fish is flakey (about 5 minutes).

Serve with crusty bread. If you want to add in a simply rouille, simply stir crushed garlic and a dash of cayenne pepper into mayonnaise.

May 24, 2012

Favourite ballet: The Sleeping Beauty

Have you noticed the recent renaissance of the fairytale? At the cinema one can see two versions of Snow White, while on television Once Upon a Time is building a solid fan base. In a recent episode I enjoyed the classic scene of Prince Charming awakening Snow White with a kiss, and it reminded me of the ballet I have loved since childhood: The Sleeping Beauty.

Composed by Tchaikovsky in 1889, the second of his three ballets (with Swan Lake and The Nutcracker), the story of the ballet is based on the classic fairytale of Sleeping Beauty. But from where did that fairytale originate?

Like many stories that have resonated through history, this was originally a folk tale that was then taken up by a writer and moulded into a fairytale. French writer Charles Perrault (1628–1703) is commonly regarded as the pioneer of the fairytale genre. He wrote and published several stories based on commonly told folk stories, including Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, Puss in Boots and the story we now know as The Sleeping Beauty, which he entitled La belle au bois dormant (The beauty sleeping in the wood).

Then, in 1812, the brothers Grimm published a collection of fairytales, and in it they included the story of Sleeping Beauty, whom they called Little Briar Rose. Various other versions exist, but it is the Grimm one that has been most dominant in popular culture.

Tchaikovsky based his ballet on the Grimm version, but he was keen to also tip his hat to the earlier Perrault story. So he included other Perrault characters in the ballet, such as Puss in Boots, Little Red Riding Hood and Cinderella. The result is a ballet that lasts four hours, which has sadly resulted in most productions cutting down Tchaikovsky’s original.

The ballet was first performed in 1890, and to this day it remains a popular choice for the world’s greatest ballet companies. Have a look on YouTube if you’d like to get a feel for the ballet – there are some wonderful recordings available there. I particularly like the Bolshoi Ballet clips, because I remember seeing this company perform when I was a girl and the experience was simply breathtaking. As a young girl I took ballet classes with my friends Colette and Miguèle for many years, and we would put on shows together – I would dream of playing Princess Aurora in the ballet, to be awoken by a kiss from Prince Florimund.

May 22, 2012

A quiet French garden for writing and dreaming

View from municipal garden near my home in France where I go to write my love scenes . Steps lead down to a deserted rocky beach where I can sunbathe.

May 21, 2012

Favourite poem: ‘The Howlers’

I love all forms of literature, from prose to poem – and one of my favourite poets is the 19th-century writer Leconte De Lisle. His poems are evocative and descriptive, which marries with my own writing style, and because he wrote about exotic locations like Africa, his verses were a great inspiration to me in writing Burning Embers.

Leconte De Lisle is not a well-known poet in the English-speaking world, and thus it is not easy to find his works translated from French. My good friend John Harding kindly agreed to translate some of De Lisle’s poem for me, and today I’m sharing with you one that really brings home the wildness and danger of deepest, darkest Africa.

‘Les Hurleurs’ is a dark poem in many respects, depicting the stark contrast of arid, burning, feverish, hungry Africa with the surge of the black, flooding sea and the empty, starless sky above. I had it in mind when I wrote of foreboding in Burning Embers, the chilling pulse of the African tom-tom drums, the terrifying might of the electrical storm. I think the poem encapsulates both the beauty of the land and its creatures together with the sense of desperation of the animals fighting to survive there – which was very much the case in 1970, when Burning Embers is set, with the tension between those who advocated and practised hunting, and those, like Rafe and Coral, who had empathy and respect for the African wildlife.

The Howlers

The sun had drowned its flames in the floods,

The town was falling asleep at the feet of the misty mountains.

Upon great rocks washed by a cloud of foam

The dark snarling sea spilt its tall billows.

The night redoubled that drawn-out wailing.

No heavenly body shone in the bare expanse;

Only the pallid moon, cleaving the cloud-bank,

Flickered forlornly like a dull lamp.

A silent world, stamped with a mark of wrath,

The shattered remnants of a dead globe randomly scattered,

It cast down from its icy sphere

A deathly reflection on the polar ocean.

Boundless, lying to the north, under the stifling skies,

Africa, sheltering under thick shadow and haze,

Let its lions hunger in the smoking sand,

And lodged its herds of elephants beside the lakes.

But on the arid beach, with its noxious odours,

Amidst the remains of bulls and horses,

Lean dogs, spread about, stretching out their muzzles,

Bewailed their lot, dolefully howling.

With their tails curled under their pulsing bellies,

Their eyes wide, trembling on their feverish legs,

Squatting here and there, all were howling, fixed in place,

And twitching momentarily with quick shudders.

The sea foam stuck to their spines

Long fur, making their backbones stand out;

And when the floods came in bounds to smite them,

Their white teeth champed under their red lips.

Before the gaze of the wandering moon with its ghastly brightness,

What unknown anguish, at the black waves’ edge,

Made a soul in your foul shapes weep?

Why did you groan, terror-stricken apparitions?

I do not know; but, O dogs that howled on the beaches,

After so many suns that will never return,

I can still hear, in the depth of my confused past,

The hopeless cry of your savage pains!

Les Hurleurs

Le soleil dans les flots avait noyé ses flammes,

La ville s’endormait aux pieds des monts brumeux.

Sur de grands rocs lavés d’un nuage écumeux

La mer sombre en grondant versait ses hautes lames.

La nuit multipliait ce long gémissement.

Nul astre ne luisait dans l’immensité nue;

Seule, la lune pâle, en écartant la nue,

Comme une morne lampe oscillait tristement.

Monde muet, marqué d’un signe de colère,

Débris d’un globe mort au hasard dispersé,

Elle laissait tomber de son orbe glacé

Un reflet sépulcral sur l’océan polaire.

Sans borne, assise au Nord, sous les cieux étouffants,

L’Afrique, s’abritant d’ombre épaisse et de brume,

Affamait ses lions dans le sable qui fume,

Et couchait près des lacs ses troupeaux d’éléphants.

Mais sur la plage aride, aux odeurs insalubres,

Parmi les ossements de boeufs et de chevaux,

De maigres chiens, épars, allongeant leurs museaux,

Se lamentaient, poussant des hurlements lugubres.

La queue en cercle sous leurs ventres palpitants,

L’oeil dilaté, tremblant sur leurs pattes fébriles,

Accroupis çà et là, tous hurlaient, immobiles,

Et d’un frisson rapide agités par instants.

L’écume de la mer collait sur leurs échines

De longs poils qui laissaient les vertèbres saillir;

Et, quand les flots par bonds les venaient assaillir,

Leurs dents blanches claquaient sous leurs rouges babines.

Devant la lune errante aux livides clartés,

Quelle angoisse inconnue, au bord des noires ondes,

Faisait pleurer une âme en vos formes immondes?

Pourquoi gémissiez-vous, spectres épouvantés?

Je ne sais; mais, ô chiens qui hurliez sur les plages,

Après tant de soleils qui ne reviendront plus,

J’entends toujours, du fond de mon passé confus,

Le cri désespéré de vos douleurs sauvages!

May 18, 2012

A Burning Embers dinner party

I was fascinated to read an article in the Huffington Post books section this week about a company called Literary Dinners, which creates ‘a pop-up restaurant for a night, specifically located for the author in question, a lavish spread and a reading (or two) from the author hosting’. What a marvellous idea!

As a keen cook and someone who enjoys fine dining, I’m always appreciative of new ways to experience food and dining with friends and family. And to bring books to the table as well… formidable! What an atmosphere that must produce, and what a unique and memorable way to get a feel for a story.

Imagine eating stew and bread in a rickety stone cottage on the Yorkshire moors, listening to Heathcliff and Cathy argue while the wind howls mournfully outside. Or savouring Georgia Peach Trifle from the Gone with the Wind Cook Book (Abbeville Press, 1991) in the grand dining room of a Southern mansion while Scarlett fights to save Tara.

How I would love to host a literary dinner myself for readers of my novel Burning Embers. We would all travel to Kenya, where we would sit on the veranda of a beautiful plantation house gazing out across the myriad colours of the land. We would dress in evening gowns and tuxedos, and put Simon and Garfunkel on the record player. We would dine to the same menu that Rafe cooks up for Coral on their first date in the book (see below). And then we would visit a local nightclub on the coast to watch authentic African dancing and drink champagne. Heaven!

May 17, 2012

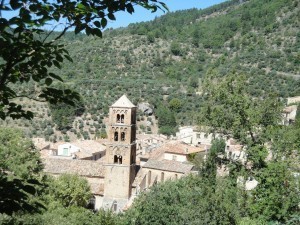

At home in France: Moustier

Moustier. While my husband and I were exploring on a sunny weekend, we discovered the most wonderful restaurant, La Bastide de Moustier. All their food is either fresh from their potager (vegetable garden) or from the local market. Their ‘Du potager à l’assiette’ (from the vegetable garden to the plate) changes every day according to what is on offer in their vegetable garden. See http://www.bastide-moustiers.com/-UN-RESTAURANT-?lang=fr.