Jack Tunney's Blog, page 26

May 30, 2014

ROBERT E. HOWARD’S CORNER MEN

ROBERT E. HOWARD’S CORNER MEN

MARK FINN

The minute I stepped ashore from the Sea Girl, merchantman, I had a hunch that there would be trouble. This hunch was caused by seeing some of the crew of the Dauntless. The men on the Dauntless have disliked the Sea Girl’s crew ever since our skipper took their captain to a cleaning on the wharfs of Zanzibar – them being narrow-minded that way. They claimed that the old man had a knuckle-duster on his right, which is ridiculous and a dirty lie. He had it on his left. ~ Robert E. Howard, The Pit of the Serpent

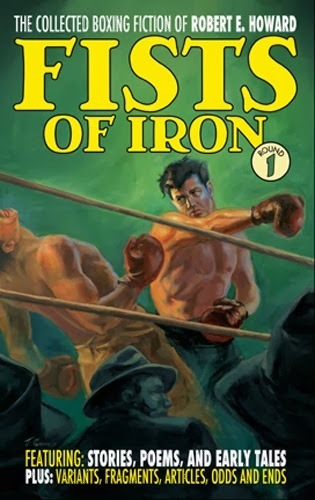

Robert E. Howard is best-known for (some would say “forever saddled with”) the creation of Conan the Cimmerian, the invention of sword and sorcery, and also the weird western. These are laudable and important things, to be sure, but what very few people know is that Howard made a good living writing and selling boxing stories in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Primarily humorous in nature, Howard’s boxing stories featuring Sailor Steve Costigan were popular and in-demand by the publishers of Fight Stories, Action Stories, Sport Story, Jack Dempsey’s Fight Magazine, and others.They were critical to Howard’s development as a writer, both creatively and financially. And now, at long last, all of Howard’s boxing fiction has been collected into a massive, four-volume set of books published by the Robert E. Howard Foundation Press.

Iron Fists: The Collected Boxing Stories of Robert E. Howard, has been a labor of love for myself and fellow editors Chris Gruber and Patrice Louinet. We have been long time champions and defenders of these stories, for a number of reasons. First and foremost, they are about boxing – and I mean, deeply mired in the language and lore of the squared circle. Howard was an amateur boxer and an enthusiastic fan of the sport, and you can tell from the second you read one of his riveting prize-fight scenes. He really knew his stuff.

Second, these stories are funny. And I don’t mean a little bit, either. I have described Sailor Steve Costigan, the champion of the merchant marine Sea Girl, as having a heart of gold, fists of steel, and a head full of rocks. Costigan is a classic unreliable narrator, and these stories are all written in first person unreliable. The malapropisms and near-swear invective, not to mention that Costigan is just not smart enough to do anything other than punch his way clear of trouble, makes these stories a joy to read.

Not all of the boxing stories are funny, though. Howard did write a number of more serious pieces exploring various aspects of what he considered made for a great boxer. One story, Iron Man, is a veritable saga that has only recently been restored to its original intended length.

So, if these stories are so great, how come you’re just hearing about them now? Great question. All I can tell you is, blame Conan. Most people are unaware of Howard’s massive output of humorous writing – over a hundred stories, including the funny boxing and his later funny western stories. Mostly because prior editors and stewards of Howard’s legacy felt it would be better to focus on Conan and the brooding young man who wrote those tales. Reading Howard’s humorous fiction casts a different light on the brooding loner who wrote of imaginary lands and strange monsters.

Over the past ten years, we’ve done what we could. I produced a series of old time radio plays featuring Sailor Steve Costigan. I wrote the introduction to Waterfront Fists, from Wildside Press. Chris Gruber edited and introduced Boxing Stories from the University of Nebraska Press. We pressured our friend Rusty Burke until he felt obliged (he insists it was convinced) to include boxing stories in the two volume Best of Robert E. Howard books from Del Rey.

All of those results brought more folks around to the boxing stories. We had new fans left and right. Sailor Steve Costigan began appearing in everyone’s list of Howard’s heroes when they were name checked. These were nice efforts, but it wasn’t enough, because there was so much boxing material that no one had ever

seen, and it was languishing. Until now.

The project took a year to do, and it’s the first publication to make full use of the Glenn Lord archive. Multiple drafts were consulted, and extra pieces and parts were discovered. Now Iron Fists will contain literally every scrap of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry that Howard wrote about boxing in his lifetime. Patrice Louinet has painstakingly consulted every page of text to determine the order in which these stories were all

written. His findings are published in a four part afterword. Gruber and I traded off on the introductions to the books. He got volumes 1 and 3. I got volumes 2 and 4. That way, we each get to talk about Steve Costigan, our favorite Howard hero. A few of the stories are now more complete, thanks to Patrice’s text corrections with the drafts that were discovered in the Glenn Lord archive. For completists, it’s your dream come true.

We couldn’t be more excited or proud.But Gruber and I aren’t stopping there. We have another project, related to the boxing stories, that I can’t tell you about right now. But suffice to say, it’ll be a unique and very relevant item that die-hard boxing fans won’t want to miss out on.

The foundation is currently offering the books as limited edition hardcovers. Depending on how fast they sell out, we may see trade paperbacks after that. For more information about the books, as well as a table of contents, you can visit the Foundation’s website here: http://www.rehfoundation.org/

SAILOR TOM SHARKEY ~ A LITERARY HISTORY

SAILOR TOM SHARKEY ~ A LITERARY HISTORY

MARK FINN

There are perhaps two dozen well-known boxing stories of substance, ranging from Jack London’s A Piece of Steak, and Fifty Grand by Ernest Hemingway, to more popular fare, such as sports writer Damon Runyan’s Bred for Battle and P.G. Wodehouse’s The Debut of Battling Billson. More recent stories by Rick Bass’ The Legend of Pig-Eye and Thom Jones’ Sonny Liston Was a Friend of Mine would surely be included, as well. Anyone wishing to expand the list to include novels would have some classic fare to choose from: Harold Robbins’ A Stone for Danny Fisher instantly springs to mind, along with the excellent book, The Bruiser by actual boxer-turned-author Jim Tully. There are a lot of boxing stories out there, along with boxing fans who are writers of one stripe or another; from Alexandre Dumas to Arthur Conan Doyle, from Norman Mailer to Joyce Carol Oates, it’s easy to find books waxing rhapsodic about the Sweet Science as literature, as metaphor, or as simply a cracking good read.

And yet, there is one name always missing from the Table of Contents pages of the Best Boxing Stories of Forever and All Time (Until We Make Another Book Just Like This One) and that’s Robert E. Howard. Most people know him, if at all, as the creator of Conan the Barbarian. They may know that he was a Texan, who wrote a bunch of pulp fiction stories in Cross Plains, Texas in the 1920s and 1930s for magazines like the legendary Weird Tales. If they know anything else, it’s that he died young, at the age of 30, by his own hand.

They almost never know he wrote over sixty boxing stories from 1926 to 1936, including some poetry, which were his bread and butter during his early writing career. Most of the stories centered on Sailor Steve Costigan, a ham and egg fighter sailing on the merchant marine Sea Girl. He – and some of his other, later fictional brothers – spent their days in the ports of call in the Asiatic Seas. They scrapped to survive, for the honor of a beautiful girl, or for a fellow sailor in trouble. Full of humor, incredible boxing sequences, and double and triple crosses, all told from the point of view of Sailor Steve himself, one of the most unreliable narrators to ever grace the page. Howard also wrote some serious boxing stories, such as the novella The Iron Man, but his meat and potatoes were found in these bawdy burlesque boxing stories.

Howard was a lifelong boxing enthusiast. He read about it, he wrote about it – hell, he nearly lived it. Himself an amateur boxer, Howard participated in a number of both gloved and bare-knuckle matches with the local roughnecks in his home town of Cross Plains. He wrote about these fights, and traveled far and wide to see local and regional matches and exhibitions. Howard even wrote a number of unfinished essays to gather his thoughts on boxing into one place. These thoughts, these ideas of Howard, while unfinished and unpublished in his lifetime, ended up elsewhere, hidden deep in his fiction as a primary motivating influence.

When I first encountered Howard’s boxing stories, I knew none of this. I was just a fan of the Texas author’s work. I’d read Conan, of course, and his other hero-kings, Bran Mak Morn, and King Kull. I was familiar with some of his other heroic writings, but I’d never seen any of his boxing stories before. The book was The Incredible Adventures of Dennis Dorgan. On the cover was a stereotypical evil oriental – a Fu Manchu villain straight from Central Casting. This was modern-day fare by way of the 1920’s. Intrigued, I bought the book and took it home.

The first story I read wasn’t the first story in the book. Instead, I skipped right over to The Destiny Gorilla, a title I maintain to this day is technically perfect for so many reasons. As soon as I started reading the story, I knew I was in uncharted waters. Gone was the florid, compact language of Howard’s dark fantasy stories. This was light, wide-open, riddled with dialect and malapropisms, and really funny dialogue. I started laughing, and I laughed all the way through the story.

I was still laughing when my roommate and fellow Howard fan came home. He put up with me for about fifteen minutes, and then demanded to know what I was doing. I gave him the book, and within two pages, he was laughing, too. We spent the rest of the evening wondering out loud why we’d never seen any of this before now. That night, we both became lifelong fans of Howard’s boxing stories. And we weren’t even reading the best of his boxing work.

Years later, when I starting looking seriously at studying and writing about Robert E. Howard, I joined what was then ground zero for such folks, REHUPA – an amateur press association that stands for the Robert E. Howard United Press Association.

When I joined, I expected to be the only person interested in the boxing stories. I was wrong. There were two others: Leo Grin and Chris Gruber. Both had come to the boxing material, just as I had, and come to the same conclusion as me – why didn’t more people know about this? In fact, we all joined with the idea of cracking open the boxing stories and showing these other Howard fans what was what.

We banded together, and right from the start, we began elevating each other’s work. There were conversations, revelations, shared information…it was heady stuff. We were the outcasts among the outcasts, writing with something to prove. We knew this stuff was great. We just had to show other people.

One of the areas of interest we shared was in sifting through Howard’s work to find his influences. His unpublished essays and stories were invaluable in this area. Chris Gruber’s essay, Atavists, All?, was a lightning rod pointing to Howard’s utilization of the kind of throw-back boxer he admired, first mentioned in the unpublished essay Men of Iron, was the model for every single Howard character in his heroic fiction canon.

Boom!

While pouring through the names of boxers in Men of Iron, Leo wrote a huge essay about Joe Grimm, who was prominently mentioned in essay. I became enamored with another real-life golden age boxer listed alongside of Grimm – Sailor Tom Sharkey. I don’t know what it was about the name, or maybe it was the story Howard included in the essay about Sharkey being knocked out of the ring on his head, and getting up to finish the fight, that intrigued me, but something took hold, and I began to research Tom Sharkey in earnest.

There was very little online about Sharkey, the most substantial piece being a biographical sketch by boxing expert Tracey Callis, alongside of his ring record. I had some boxing reference books in my personal library already, including a great encyclopedia from The Ring, the Bible of boxing, and a magazine Howard read regularly in his day. Inside was an amazing picture of Tom Sharkey, after a fight, standing straight and tall, like he was having a mug shot taken. He was battered, crunched, and bruised, but everything I could see in his curiously shaped head and face and thick-as-a-bull neck made me proclaim, “Tom Sharkey, hell, that’s Sailor Steve Costigan!”

And thus began my quest. I chased down every scrap of information I could find about Sharkey. He was one of the most feared and respected boxers in the Golden Age of the sport – just after the reign of John L. Sullivan.

Sharkey trod the squared circle with the likes of Gentleman Jim Corbett, Bob Fitzsimmons, and – perhaps his greatest nemesis – Jim Jeffries. These were some of the biggest, hardest hitting fighters of all time. And they all said Sailor Tom Sharkey gave them their toughest fights.

Standing only 5’8” or 5’9” depending on who you ask, Sharkey had a 46” chest and thick, muscled arms he honed from his years at sea in the merchant marine, and later, the U.S. Navy. Born in Dundalk, Ireland, in 1874, he ran away at the age of 12, and managed to make it all the way to America as a sailor by the time he was 17. He traded briefly as a blacksmith before signing on to a hitch in the Navy. When he arrived in San Francisco, two years later, he was ready to begin his fighting career in earnest.

Because of his size, and his Irish accent, no one took him very seriously at first. Even then, there was a frequently debunked myth that all sailors were decent brawlers, but against an actual student of boxing, stood little chance. Sharkey wasn’t the best public speaker, and he looked like a dub – his chest, for example, was festooned with a tattoo of a four-masted schooner and the motto, Never Give Up the Ship. He was Popeye twenty years before E.C. Segar created Thimble Theater.

Sharkey’s initial matches were literally intended to be good sport for better boxers and nothing else. But Sharkey surprised them all when he charged the local champions and kept them on the run for eight straight rounds. He could absorb massive amounts of punishment, and his punch was devastating. Early opponents learned this the hard way after waking up on the canvas, wondering what hit them. Sharkey quickly rose through the ranks to become a contender in San Francisco. He had his eye set on the heavyweight championship.

His professional career was as controversial as it was colorful and storied. Sharkey wasn’t so much a fighter as he was a force of nature. His preferred method of boxing was to come out swinging and not stop until his opponent was down. He didn’t mind taking a few punches in order to get in close with those tree trunk arms and that fireplug torso and whale away on the other guy’s ribcage – and if a couple of kidney punches landed, too, well, no hard feelings, eh?

Not quite. Fouls, low blows, and other controversies dogged Sharkey and made other opponents wary of stepping into the ring with the Irish scrapper. His reputation notwithstanding, Sharkey tried several times to wrest the belt from champions, only to end in bitter defeat. One of his most bizarre fights was against lanky Bob Fitzsimmons, another blacksmith-turned-boxer whose punch was legendary, despite his unassuming appearance.

The match, refereed by none other than Wild West lawman Wyatt Earp, was awarded to Fitzsimmons because of a low blow thrown by Sharkey that Earp observed. The incident actually ended up on court, with Sharkey alleging Fitzsimmons faked the injury because he knew Sharkey would beat him. The judge abided by the decision, and Sharkey never got a rematch with Fitz.

But the most storied battles of Sharkey’s career were his two brutal fights with Jim Jeffries. The second fight, in particular, is the stuff of legend. It was the first boxing match filmed and shown in movie theaters. The Klieg lights used to illuminate the ring were so bright and intense that it singed both men’s scalps. Sharkey fought Jeffries to a standstill in 25 grueling rounds that nearly did both boxers in. Sharkey fought the last four rounds with three broken ribs. He was certain he’d beat Jeffries, but the referee didn’t agree. Afterwards, even on the mend, Sharkey threatened to throw the ref into the Atlantic Ocean if he ever caught up with him.

Sharkey’s post boxing career was just as colorful, and involved him opening clubs, getting embroiled in Tammany Hall politics in New York City, betting large sums of money on the horses, getting married twice, widowed once, and divorced once, and later, in his fifties, going on the Vaudeville Circuit with former nemesis Jim Jeffries and recounting their famous fights for the crowds.

Sharkey loved to spin yarns, and some of those he told people over the years were colorful and, um, hard to prove, such as the notion he was shipwrecked four times in the Merchant Marine. Over the years, sports writers, reporters, and fellow boxers had amusing Tom Sharkey stories to tell. Most are affectionate in their good humor. Some are just downright funny.

These anecdotes and snippets were all published during the time Robert E. Howard was reading about boxing. I was certain I’d found the framework upon which he built Sailor Steve Costigan. These findings and essays made their way into various books, introductions, and lectures.

By this time, I’d corresponded with most of the people who had written anything about Tom Sharkey, including the author of the first real biography of the man, I Fought Them All: the Life and Ring Battles of Prizefighting Legend Tom Sharkey, Greg Lewis. To a person, they were all happy to share in their research and enthusiasm for this colorful fighter.

At this point, I’d been engaged in this pursuit, on and off, for five or six years. As my file on Tom Sharkey grew ever larger, and my parallel study of Howard’s boxing went ever deeper, I felt an urge to write some funny boxing stories of my own start to take hold in my brain.

This was folly, of course, and I’ll tell you why. It has been scientifically proven over the years that one cannot copy the writing style of Robert E. Howard. It just can’t be done, and we know this, because it was tried…a lot…with terrible, terrible results.

Howard’s writing style was literary lighting in a bottle. It was alchemy. Mercurial. It can be imitated, to some degree, but it can never be duplicated. The reason for this is simple – no one writes from the head space from which Howard wrote. His work was very personal, and unless you have the exact same set of interests, pressures, and irritants, you’ll never make pearls the way Howard made them.

Add to that the fact that doing a Sailor Steve Costigan story involved writing funny, and you’ll see the task is nigh-impossible. Writing in someone else’s humor style is even harder than writing in someone else’s literary style, and if you tried to do a Sailor Steve Costigan story, you’d have to do both. I’m no fool. Whatever marginal cache I had as a Howardist would be shattered if I tried to write something in the style of Robert E. Howard, a practice I’d publically pooh-poohed many times.

No, if I was going to do a humorous boxing story, it would have to be original. My own thing. I knew I could write about the fights, and I was pretty sure I could make it funny in my particular way, but I was floundering as to what this boxer would look like, and how he’d actually be different from Sailor Steve.

The inspiration came to me during a writer’s retreat in 2007. My former writing group and publishing consortium, Clockwork Storybook, got together at Naulakha, Rudyard Kipling’s house in Dummerston, Vermont, and we spent a week in seclusion, writing and critiquing, just like the old days.

Literally three days before we were set to meet up, it occurred to me there was no better unreliable narrator than Tom Sharkey himself. He went around the world, did all of these amazing things, and like any old campaigner worth his salt, wasn’t going to let the truth get in the way of a good story.

There were a lot of “blank spaces” on Tom Sharkey’s map – periods of time no one can account for, including the years he spent with a traveling carnival, recreating (and sometimes rehashing, at the age of fifty, no less) his fights with Jim Jeffries.

I wrote the first Tom Sharkey story – what would become Sailor Tom Sharkey and the Introduction Window (the original title was An Excerpt from the Unexpurgated Adventures of Sailor Tom Sharkey) – right before I left for Vermont.

I planned to read it for the guys, and get their notes. During the retreat, I wrote another story based on a writing challenge we all set for ourselves. This one, The Final Adventure of Sailor Tom Sharkey, has since been renamed Sailor Tom Sharkey and the Real McCoy. It has also been edited and rewritten somewhat to strip out most of the challenge conditions of the exercise. I kept the cow skull, though, which worked out quite well.

When I read the group my first Tom Sharkey story, it was with very little preamble. I just told them this was something I’d been working up to for a while. To my complete surprise and pleasure, they loved it. Most of the comments were along the lines of, “I can’t tell if this is good writing from you or not, because it sounds just like you.” The second story, written a few days into the retreat, met with similar notes and a caution to be careful not to have them all sound alike. “I mean, how often can you write about a big dumb sailor who doesn’t ever get what’s going on around him?” one of them quipped. Oh, ye of little faith.

Other Tom Sharkey stories began to suggest themselves, and I dutifully noted them down when inspiration struck. The hardest part of writing Tom Sharkey is avoiding “Costigan Creep,” when certain key phrases and things find their way, in quantity, into the stories. Do it once and it’s a nice little Easter egg nod to fans in the know. Do it twice, or thrice, and then it becomes second-rate Robert E. Howard. More than once I’ve had to pull myself back, all in service to the story.

I should also mention that over the span of several years and several stories, my fictitious Sailor Tom Sharkey has taken on a life of his own, one that is suggested by the real fighter, but has in the retelling become someone else altogether.

I’ve based many of these stories on real events in Sharkey’s life, but these are in no way intended to represent real people or real events, and none of the stories in this collection are intended to supplant the real Tom Sharkey’s biography in any way. If you want the details of the man behind the legends, see Greg Lewis’ book, mentioned above.

In between writing other things, I’d occasionally let one fly, and when finished, I sent each one far and wide, looking for a home. They were, not surprisingly, hard to place. There is not, nor has there ever been, a sub-genre of the literature section labeled “humorous historical weird boxing stories.” An oversight, no doubt.

My submissions, to editors of big and little stature, all came back rejected. Those that added any commentary frequently told me they liked the story, but had no idea what to do with it. I wasn’t surprised. These have been a hard sell.

And yet, every time I write a new Tom Sharkey story, and read it at conventions or other personal appearances, I get laughs and interest. “When are you going to collect these?” “Where can I read more?”

Thank heaven for Fight Card. Now, at last, you can.

I’m grateful to Paul Bishop for giving me the chance to publish this collection under the aegis of what has become a respected line of quality fight fiction, and ground zero for fans of this kind of literature. If you are such a fan (and why wouldn’t you be?) and you have not read Robert E. Howard’s boxing stories, you really need to. You’re missing out on one of the most memorable and critically underrated achievements from one of the world’s greatest pulp fiction writers. If you’re already one of us, then I hope you’ll enjoy these stories in the spirit in which I wrote them.

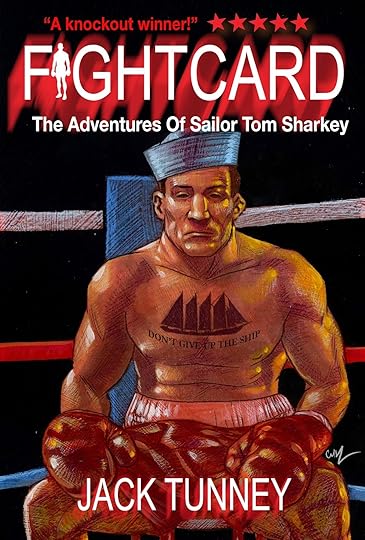

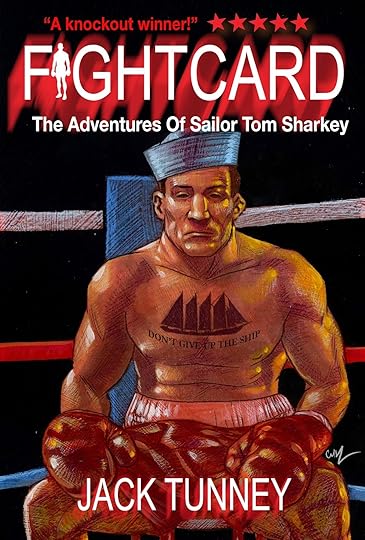

COMING SOON ~ FIGHT CARD: THE ADVENTURES OF SAILOR TOM SHARKEY!

COMING IN JUNE 2014

THE ADVENTURES OF SAILOR TOM SHARKEY

MARK FINN WRITING AS JACK TUNNEY

COVER BY CARL YONDER

7 HARD-PUNCHING TALES

THE BEST WEIRD, HISTORICAL, HUMOROUS,

BOXING STORIES

YOU’LL EVER READ!

He was one of the greatest heavyweight boxers to enter the legendary squared circle during the Golden Age of Boxing. Standing a mere 5’ 8”, Sailor Tom Sharkey was one of boxing’s most feared opponents…Gentleman Jim Corbett, Bob Fitzsimmons, Kid McCoy, and Jim Jeffries all agreed he was their fiercest opponent and gave them their toughest fights. A colorful boxer both in the ring and out, he retired in 1904 after several legendary and controversial failed attempts to win the championship belt.

That’s the story you know – But it’s not the end of Sharkey’s story – not by a long shot…In the tradition of Robert E. Howard’s humorous Sailor Steve Costigan boxing tales, this action-packed collection of rowdy, bawdy, burlesque, tall Texas tall feature Sailor Tom Sharkey’s adventures after he hung up his professional gloves.

Thrill to Sharkey’s brush with Hollywood’s “It” Girl, Clara Bow…Get chills as Sharkey and Kid McCoy faces down a maniacal bandit…Feel the heat as Sharkey rides the rails with Jim Jeffries and the Vaudeville Carnival into a clashes with a mad scientists and mummified menaces…Watch as Sharkey plays Santa Claus to a bunch of Tammany Hall orphans and end up with a tiger by the tail – literally – and much more!

These are the Untold Tales of the Wildest Tale-Teller of Boxing’s Golden Age!

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Mark Finn is an author, actor, essayist, and playwright. He is over forty and has no tattoos. With his long-suffering wife, far too many books, and an affable American bull terrier named Sonya, he lives in North Texas atop an old movie theater.

May 9, 2014

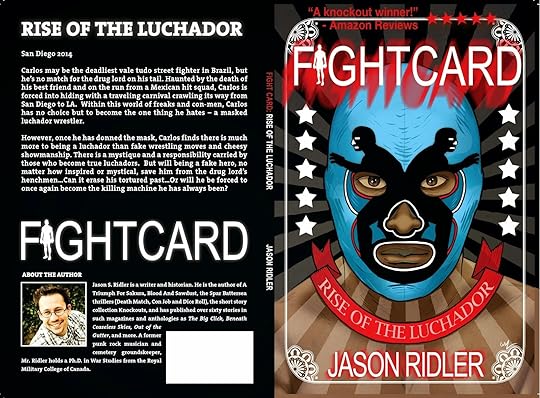

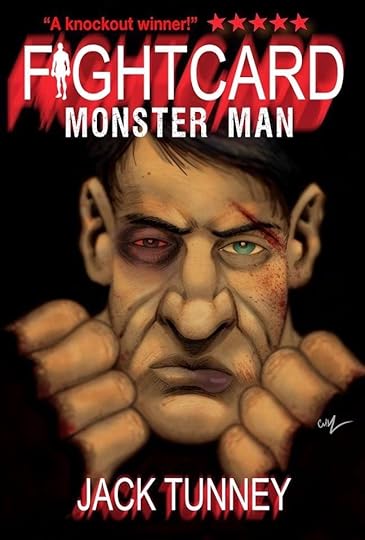

AVAILABLE NOW ~ FIGHT CARD: MONSTER MAN

AVAILABLE NOW ~ FIGHT CARD: MONSTER MAN

JASON CHIREVAS

WRITING AS

JACK TUNNEY

Albuquerque, 1947

A fighter on the rise despite a growing illness, Ben Harman is on track for a heavyweight title shot until one disastrous night in New Mexico ends his chance at glory, and his pro career, in one overhand right.

Mamaroneck, 1953

Along with Pete – his manager and fellow refugee from Chicago’s St. Vincent’s Asylum for Boys – Ben lands north of New York City in the harbor town of Mamaroneck. This will be the latest underground boxing hot spot to fall victim to Pete and Ben’s scam. The scam is simple – it keeps Pete and Ben ahead of what happened in Albuquerque and, hopefully, ahead of the acromegaly twisting and weakening Ben’s body by the punch. Move and scam, move and scam, has always been their plan.

Then Ben meets Vicky, a fallen Hollywood day player able to see past Ben’s monstrous exterior to the man inside. As their romance grows, Ben and Vicky threaten to derail the perfect meal ticket Pete’s concocted, and Vicky’s connection to the man running Mamaroneck’s illegal fights – and the secret they share – puts everyone in danger.

Time is running out. With only so many punches left in his distorting hands, Ben Harman will have to decide how to use them – as a monster or as a man.

May 4, 2014

THE MONSTER INSIDE US

THE MONSTER INSIDE US

JASON CHIREVAS ON WRITING

FIGHT CARD: MONSTER MAN

I’ve always found losers more interesting than winners. Let’s start there.

Fight Card: Monster Man is a story about losers. Losers of varying degree, but losers nonetheless. The only character in the book who may be doing what he wants to do, who has achieved what he set out to achieve, is the villain of the piece. That’s should tell you what to expect in this story.

But then, that’s noir, isn’t it?

And noir is one of the things that drew me to Fight Card.

Pulp and noir – two terms thrown together a lot, but which don’t really have much in common – collide head-on in the traditional Fight Card books. When I pitched Monster Man, I knew three things – I wanted it be noir; I wanted it to evoke pulpy Hollywood B pictures of the 40’s and 50’s; and I wanted it to be about losers.

Another thing I’ve always found interesting is the good guy trapped in a hulking body. It’s easy to write and envision a big, muscle-bound, guy as a thug or a villain – but what if Goliath is the good guy? That paradigm shift was what I wanted to explore in Monster Man. It was also the biggest challenge – how to take a big, hulking, boxer and not only make him the hero, but also make him a loser?

Enter Rondo Hatton.

Rondo Hatton was an actor in several second and third-rate horror movies in the 1940s. Hatton had a disease called acromegaly – essentially a form of gigantism – which gave him a menacing, distorted appearance. Hollywood exploited this feature, casting Hatton as some variation of a monstrous character called The Creeper in most of his movies with little more than lighting needed to make him look like something underworldly. Hatton’s success, if that’s what it was, was short-lived as he died of an acromegaly-releated heart attack in 1946 at the age of 51.

A big, hulking, boxer with acromegaly. The idea fascinated me. But, as Fight Card guru Paul Bishop asked, was it possible for such a person to actually box?

My answer – Primo Carnera was the heavyweight champion of the world from 1933 to 1934. He was 6’ 7” tall. He also had acromegaly.

Now, if you choose to read up on Primo, you will find his rise to the title may have had some influence from the mob, but the real reality was Primo Carnera was a huge guy, with acromegaly, who got in the ring and banged it out with guys like Jack Sharkey and Max Baer.

Plus, mob influence – how noir is that?

So, with a real-world precedent in place, Ben Monster Harman was born. Ben is a big, hulking guy who learned the disciplines of fitness and boxing from Father Tim at St. Vincent’s Asylum for Boys in Chicago. Like a lot of Father’s Tim’s boys you’ve read about, Ben looks to the pro ranks for his salvation when he’s old enough to leave the asylum. However, World War II and then the illness – which he comes to call Hatton’s disease – puts an expiration date on Ben’s time as a boxer.

So, that’s Ben. But he’s not the only desperate noir loser trying to fight his way through Fight Card: Monster Man.

The person just past his or her prime is another concept of fascination for me. In Monster Man, we also meet Victoria – a never-quite-wise movie actress who settles uncomfortably in the harbor village of Mamaroneck, New York.

Sparks fly when Victoria meets Ben, who is in town to perpetuate an underground boxing scam with Pete – who is Ben’s manager and also a fellow refugee from St. Vincent’s.

The idea of two losers – both fallen from different walks of life, which might have granted them some celebrity – trying to use whatever they have left to get ahead, really interested me. It made me care about the characters and what would become of them as they make choices that put them on a slippery path to disaster.

At their best, I think B movies and the kind of fiction Fight Card represents are great for two reasons, both arising from their brevity. First, the short running times and page counts force writers to power the plot along at lean, stripped-down pace. Second, events move so quickly, and circumstances are usually so dire, it forces the characters to expose their raw, base selves. Crisis is when you learn who someone really is and humans in crisis is what Fight Card is all about. We put our fighters – and the people who love them – through hell, turning and turn the story on its head before you, or they, have time to react.

Monster Man was a fun book to write and I hope some measure of that enjoyment will carry over when you read it. I’m proud to be part of Fight Card. It’s exactly the kind of fiction I always wanted to write and I’m happy to see I wasn’t alone.

Keep punching, Ben. You and Vicky may find a way to win yet.

COMING SOON IN PAPERBACK

April 18, 2014

COMING IN MAY ~ FIGHT CARD: MONSTER MAN

April 16, 2014

COMING SOON IN PAPERBACK!

April 1, 2014

COMING SOON ~ FIGHT CARD: AUDIO!

APRIL FIGHT CARD UPDATE

APRIL FIGHT CARD UPDATE

Our latest release Fight Card: Copper Mountain Champ by Brian Drake (writing as Jack Tunney) has just hit the virtual shelves. Brian is another of the top breakthrough writers to become part of our Fight Card team.

FIGHT CARD: COPPER MOUNTAIN CHAMP

Butte, Montana. 1951…Back from the horror of World War II, Alex Slayton started working the copper mines of his hometown, but it’s hardly the life he intends for himself…or his girlfriend, Liz. However, when long festering problems at the mine force a union strike, Alex finds himself up against the mining company’s notoriously tight-fisted owner – a man who believes in violence as a first resort.

Based on his raw fighting talent, Alex learned the sweet science from his mentor and fellow miner, Pete Kovich – hoping boxing would get him out from underground and on to a sunny future. Now, caught in a web of town intrigue, violence, and sudden death, Alex is forced to face the mine owner’s son, a top boxing prospect, in the ring. Alex knows he’s not ready, but the only way out is to fight – not just for himself, but for the whole town…

Any exposure is appreciated. Please use the appropriate sharing buttons at the bottom of each page at www.fightcardbooks.com to spread the word via Facebook and Twitter.

Coming up next month (May) will be Fight Card: Monster Man from Jason Chirevas with a distinctive storyline, which takes the Fight Card formula in a very different direction.

June will see Fight Card making a big splash at the Howard Day’s convention in Cross Plains, Texas, with the debut of Fight Card: The Adventures of Sailor Tom Sharkey by Howard scholar Mark Finn. The Fight Card tales owe a big debt to Robert E. Howard’s early creation of Sailor Steve Corrigan. Finn’s Sharkey tales pay tribute to the world and style of Corrigan, but with a distinct voice all their own. I’m personally very excited about this collection, which sports an amazing painted cover from Carl Yonder.

Also coming up later in 2014, Fight Card: Guns of November by returning Fight Card author (Fight Card: The Last Round of Archie Mannis) Joseph Grant – in which Fight Card enters the murky waters of the JFK assassination – Fight Card: Bridgetown Brawler from rising pulp star David White, and Fight Card: Fight River from pulp guru Tommy Hancock.

This summer, Fight Card will be the focus of an intensive five week college marketing workshop known as The Space. Jeremy L.C. Jones and I will be working with these top marketing students to come up with new ways to promote our Fight Card brand and generate more book sales for all of us.

Till next month … Keep Punching!