Midori Snyder's Blog, page 34

June 17, 2016

Encounters with the Fantastic in the Art and Animation of Camille Andre

First, watch this stunning animated short film "Nebula" by a young French artist, Camille Andr��, whose work, while being so original also carries the echoes of a Remedios Varo mixed with a Miyazaki sort of feel. Nature is luminous and enveloping, but with a gentle touch. The figures are constantly in motion, even in the stills, they flow. "Nebula" was Andre's graduation piece -- and I for one cannot wait to see more of her beautiful work in the future.

June 4, 2016

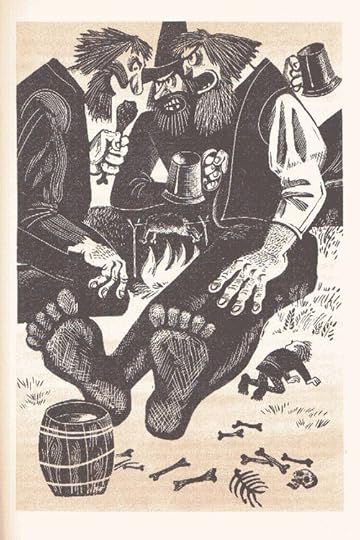

The 1976 Soviet Illustrated Edition of The Hobbit.

Mashable has a wonderful post on the surprising 1976 Soviet edition of Tolkien's The Hobbit. The illustrations are so charming, more intended for young adult audience, and certainly as far from the usual Soviet Social Realism of the era. These images hark back more to the fairy tale tradition of robust and evocative illustrations, with so much personality and life to them, from Bilbo's furry feet, the quarreling trolls, and the salamander-looking Golem. I also love the smaller chapter headings and end pieces -- delightful small portraits of the dwarves.

June 2, 2016

A Froud-ian Moment.

And on another Sunday afternoon up in the mountains, hiking through the pines, this creature showed up on the underside of an uprooted tree. Somewhere between Owl and one of Brian Froud's woodland creatures.

And this beautiful Serpentine Tree, lifting out of the ground.

June 1, 2016

Inscribing the Body with Bio Compatible Silk

This is a astonishing project by poet Jen Bervin, who travels to different countries to learn about the traditional methods of silk cultivation, from the trees to the spinning worms in their silky-sticky cocoons -- and then home again to see the remarkable cutting-edge technologies made with silk. Discovered to be bio-compatible with the human body, silk has incredible possibilities for medical use. As a poet, Bervin sees unique and breath-taking applications of silk combined with poetry.

May 30, 2016

Orality and The Singer of Tales.

I am continuing with my notes on reading Walter Ong's Orality and Literacy, with some sidesteps to look at authors, whose work Ong references: Milman Parry and Albert Lord whose Singer of Tales is a fascinating study not only of the structure of Homer's Illiad and The Odyssey, but also the important use of mnemonic devices in works that are orally performed and transmitted. So here are the key interesting ideas for me:

Milman Parry analysing Homer's Illiad and The Odyssey discover that every distinctive feature of Homer's poetry is due to the economy enforced on it by oral methods of composition. These were never performed exactly the same, as poets in an oral culture normally do not "memorize" the text, but "stitched together prefabricated parts." They recognized a collection of epithets (so many versions of "the wine-red sea") that had different metre lengths and could be used anywhere in the text as the poetry required. This certainly makes sense to me where both epics and tales were highly patterned -- usually the only consistent feature of different collected variants of the same epic or story. According to Harold Scheub's observations, even a child of five can be a reasonable good story teller because she will have learned the patterning of the narrative, having it heard it repeated with every telling.

Ong argues: "Homeric Greeks valued cliches because not only poets but the entire oral noetic world or thought world relied upon the formulaic constitution of thought. In an oral culture, knowledge once acquired, had to be constantly repeated or would be lost. But I would add, that the repetition itself, needed to be evocative and interesting, gathering a certain set of emotions out of the listener in order to engage them. This becomes art, rather than a list of items to be recalled. Ong expresses David Bynum's ideas, (The Daemon in the Wood (1978) that "the clusters constitute the organizing principles of the formulas, so that the essential idea is not subject to clear straightforward formulation but is rather a kind of fictional complex held together largely in the unconscious." And so strong is the idea of the formulaic portions of story telling that "they ride deep in the conscious and unconscious" and don't vanish the moment literacy is introduced, but often are reproduced even in early written form by those from the oral culture who have learned to write --mimicking at times the oral performance. (Amos Tutuola's brillant The Palm Wine Drunkard is a great example of this -- although in Nigeria he received criticism, particularly from educated Nigerians because of what was perceived as low-class, uneducated English.)

I find this particularly interesting because when a fairy tale is transformed from its oral version (which ironically we can only read in transcribed texts) into a literary tale, it runs the risk of losing its profound evocative nature. Repetition and patterning into forms organizes the details of the story, creating tension when the human and the fantastic interact -- emphasizing not just the surface movement of of the tale, but all the complicated feelings such arrangements of images bring forth to the listener. In some ways, it is closer to music (or indeed, singing the tale) -- we are aware of the patterning, the phrases, the way they move from introduction, to increasing complicated arrangements and then return -- a coda-- which feels like the beginning but isn't because of the experience of the journey to get to the end. There is for the analyst, the social message -- what is the story trying to tell us? But I think it's more a case of how is the story making us experience, feel through its techniques our life as lived in that moment of the telling. And perhaps, since that is always changing, we can listen even to the same tale over and over, finding in it something new.

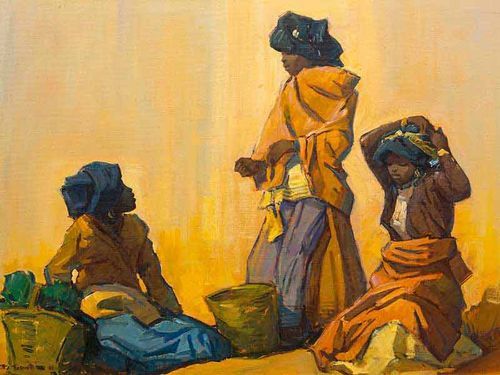

Photo: "Griot" �� Emile Snyder, 1963, Tittia Frasciotti, Galekea Women, 1988.

May 22, 2016

Up in the Mountains

We went on Sunday to the top of Mt. Lemmon in the Catalina Mountain range that borders one side of Tucson. Up at about 9,000 feet, the air is so cool and the pines scented with spring. We took the Meadow hike that wanders through fields of pine, low shrubs, ferns (most of which were newly unfurled) and wild flowers starting to bring out their blossoms for show.

There are sections up here (and I say that because you can't quite escape the vertigo of altitude) when walking close to the edge of the mountain path, and display an ocean of low hills, distant mountain ranges. There had been a terrible fire up there about eight years ago and the area is still recovering. There are stark, leafless trees burned grey by the fires, but many have now been cut and left to lie on a greening forest floor to compost and serve as home to insects and smaller creatures. Beneath the shade of the standing trees the grass is so green. I took photos of the place -- the very large and the very small details of the forest returning to itself.

In the photo above, I found a wonderful shelf mushroom, that usually grows parallel to the ground from where it attaches to the tree trunk. But in the cutting and clearing of burned trees, this lovely ear-shaped mushroom landed by itself on the ground. I could resist holding it up to my own ear, hoping to the forest, the way one hopes for the sea in the hollow of a shell. The first photo below looked like a mountain dragon -- his small eye and fierce red grin, with scaled ears.

May 17, 2016

The Perfect Passage

I so enjoy reading John Le Carre whose masterful writing offers a lesson in how to write with precision, creating layers of meaning in finely honed phrases. Here is the opening passage from The Perfect Spy, a seemingly straightforward account of a man, Marcus Pym, striding across a square on a rainy evening, headed toward a rooming house where he is a regular visitor when in town. Here is how Le Carre tells us so much about the man without actually describing who and more importantly, what he is:

I so enjoy reading John Le Carre whose masterful writing offers a lesson in how to write with precision, creating layers of meaning in finely honed phrases. Here is the opening passage from The Perfect Spy, a seemingly straightforward account of a man, Marcus Pym, striding across a square on a rainy evening, headed toward a rooming house where he is a regular visitor when in town. Here is how Le Carre tells us so much about the man without actually describing who and more importantly, what he is:

"Reaching the porch of a house marked "No Vacancies" he pressed the bell and waited, first for the outside light to go on, then for the chains to be unfastened from inside. While he waited a church clock began striking five. As if in answer to its summons Pym turned on his heel and stared back at the square. At the graceless tower of the Baptist church posturing against the racing clouds. At the writhing monkey-puzzle trees, pride of the ornamental gardens. At the empty bandstand. At the bus shelter. At the dark patches of the side streets. At the doorways one by one. "

Pym is a man who notices everything -- and prioritizes the observations of his surroundings. He moves from the most visible to the least, from the largest most obvious spaces, to the smallest and darkest corners -- the tension increasing with each repetition of the short phrases beginning with "At the..." And it is chilling to follow that gaze as the space and locations become more secretive and hidden. It is Le Carre's focus -- not on the man, but the objects of Pym's gaze that reveal the habits of a spy, and establish the character well before he has spoken a word.

The door to the rooming house is opened by an elderly woman, who pulls him into the front hall, complaining about his dripping coat and wet shoes, and the late hour. But they know each other, and he is comfortable in her grumbling. Le Carre dscribes her: "Like many tyrants Miss Dubber was small." -- which as the shortest alpha in our house, made me laugh out loud.

May 10, 2016

Orality and Literacy: The Sound of Language.

As part of preparing for my talk at Mythcon -- which will be focusing on the re-interpretation of myths in modern literature, especially as this is the anniversary of C. S. Lewis' brilliant novel Till We Have Faces, based on the myth of Cupid and Psyche -- I have been reading widely in the histories and structures of myth and oral narratives as a foundation. As an undergrad getting a degree in history, I was drawn to oral history, and later in graduate school, studied African oral narratives (under the very knowledgeable Harold Scheub). And then there is my own work as a writer -- and in doing academic reading again, I have been realizing how much my fiction has been shaped by oral narrative traditions.

True, I read the transcriptions of folktales in text (and often, translation) but was really moved when I combined the narratives with their cousins in songs and ballads -- which only come truly alive when sung. Whenever I have been in a gestational phase of writing, I am always singing to myself, to the dishes, to the knitting in my hands, to the folding of laundry...and without fail, some detail or image from singing and hearing the song, winds up in my work. It is an intimate conversation between the words, the tune, the past and whatever emotion fills my responding heart. It is such an odd, transcendent feeling -- the words on the page can not convey the same intensity of the words sung. And maybe it is just that -- the ephemeral nature of the utterance that makes us hang on it, that the emotional experience is in the moment of singing, not the contemplation of what it means afterward.

So I am reading Walter Ong -- whose insightful work Orality and Literacy has stood up very well over the last thirty years since its publication. In a style that is accessible, sharp, and witty, Ong examines the relationship between two camps -- traditional oral expression and the impact of literacy and the written word. Here are a few of the notes from the first chapter that I find most interesting:

1.The basic orality of language is permanent. Even in writing, words are made up of phonemes --functional sound units rather than letters. We reproduce the sound of the word (often in our head, especially if writing in a coffee shop) when it's read or written. So because of this connection of sound to text, writing can never dispense with orality. Writing is dependent upon a prior system of spoken language, but the oral expression can and has existed fully without any writing at all.

2. Written words are the residue (we can see and touch in texts) of oral speech transferred into grapholects, for in an oral society, when a story is not being told, all that exists is the potential in certain people to tell it. Writing gives rise to the ability to study, but in the oral tradition where texts do not exist, there is apprenticeship to actively transfer knowledge.

3. The term "oral literature" is an oxymoron arising out of an academic need to harness oral art to the more familiar act of writing. Yet, the word "literature" means "writing" in Latin, derived from "litera" -- or letter of the alphabet. ( Scheub argued this often, that the oral arts needed to be understood on their own terms, not as red-headed step-children to the written text.) Ong sums up the academic misdirection thus: "Thinking of oral tradition or a heritage of oral perfomance, genres, and styles as "oral literature" is rather like thinking of horses as automobiles without wheels."

4. There is a tension between the literate who can't imagine a world without the written word, the ability to store information (exactly as I am doing now), to look up words in a lexicon versus those of a truly oral society (though fewer now exist who have not been exposed to the dominance of literacy). It's true also, that oral languages have developed a high degree of grammatical complexity and elaborations without any help of written or visual translations of oral sounds.

5.There is a sadness in recognizing the diminishment of oral languages -- and with them the cultural legacies embodied in the oral performances. For members of an oral society to survive in the future, they must become literate -- and it then becomes even more important for literacy to restore memory and "to reconstruct for ourselves the pristine human consciousness which was not literate at all --at least to reconstruct this consciousness pretty well, though not perfectly... and bring a better understanding of what literacy has meant in shaping man's consciousness toward and in high-technological cultures."

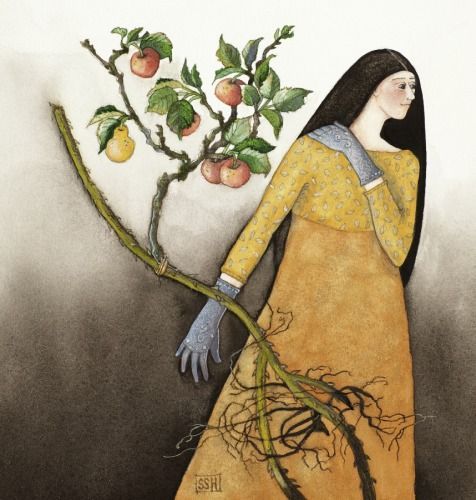

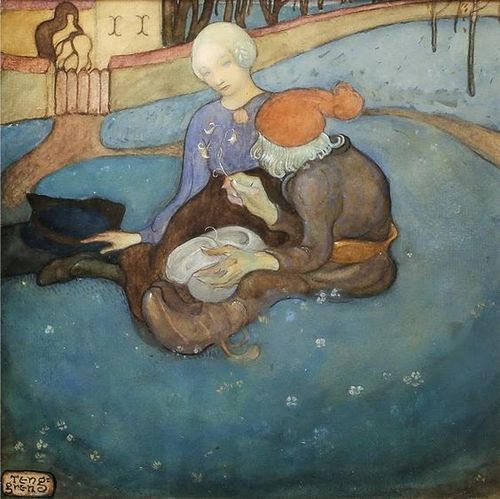

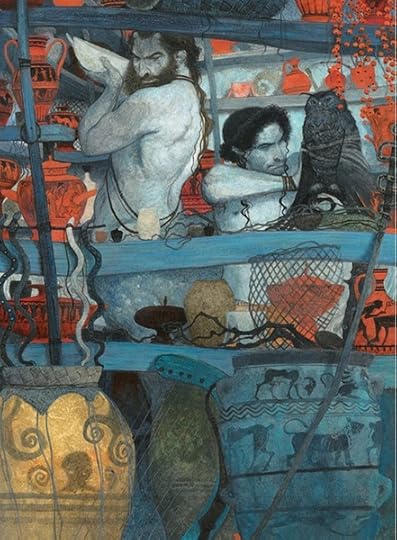

Orality and Literacy, The Technologizing of the Word, Walter Ong, Routledge Press, 2002, Art: Ida Rentoul Outhwaite (1888-1960), Susan Sorrell Hill, "Girl with Silver Hands," Gustaf Tenggren 1959, Svetlin Vassilev, Greek Myths.

Orality and Literacy

As part of preparing for my talk at Mythcon -- which will be focusing on the re-interpretation of myths in modern literature, especially as this is the anniversary of C. S. Lewis' brilliant novel Till We Have Faces, based on the myth of Cupid and Psyche. My own intellectual journey is more old school -- even as an undergrad I was drawn to oral history, and later, I studied African oral narratives in graduate school (under the very knowledgeable Harold Scheub.) And then there is my own work as a writer -- and in doing academic reading again, realizing how much my fiction has been shaped by oral narrative traditions.

True, I read the transcriptions of folktales in text (and often, translation) but was really moved when I combined the narratives with their cousins in songs and ballads -- which only come truly alive when sung. Whenever I have been in a gestational phase of writing, I am always singing to myself, to the dishes, to the knitting in my hands, to the folding of laundry...and without fail, some detail or image from singing and hearing the song, winds up in my work. It is an intimate conversation between the words, the tune, the past and whatever emotion my responding heart. It is such an odd, transcendent feeling -- the words on the page can not convey the same intensity of the words sung. And maybe it is just that -- the ephemeral nature of the utterance that makes us hang on it, that the emotional experience is in the moment of singing, not the contemplation of what it means afterward.

So I am reading Walter Ong -- whose insightful work Orality and Literacy has stood up very well over the last thirty years since its publication. In a style that is accessible, sharp, and witty, Ong examines the relationship between two camps -- traditional oral expression and the impact of literacy and the written word. Here are a few of the notes from the first chapter that I find most interesting:

1.The basic orality of language is permanent. Even in writing, words are made up of phonemes --functional sound units rather than letters. We reproduce the sound of the word (often in our head, especially if writing in a coffe shop) when it's read or written. So because of this connection of sound to text, writing can never dispense with orality. Writing is dependent upon a prior system of spoken language, but the oral expression can and has existed fully without any writing at all.

2. Written words are the residue (we can see and touch in texts) of oral speech transferred into grapholects, for in an oral society, when a story is not being told, all that exists is the potential in certain people to tell it. Writing gives rise to the ability to study, but in the oral tradition where texts do not exists, there is apprenticeship to actively transfer knowledge.

3. The term "oral literature" is an oxymoron arising out of an academic need to harness oral art to the more familiar act of writing. Yet, the word "literature" means "writing" in Latin, derived from "litera" -- or letter of the alphabet. ( Scheub argued this often, that the oral arts needed to be understood on their own terms, not as red-headed step-children to the written text.) Ong's sums up the academic misdirection thus: "Thinking of oral tradition or a heritage of oral perfomance, genres, and styles as "oral literature" is rather like thinking of horses as automobiles without wheels."

4. There is a tension between the literate who can't image a world without the written word, the ability to store information (as I am even doing now), to look up words in a lexicon and those of a truly oral society (though fewer now exist who have not been exposed to the dominance of literacy). It's true also, that oral languages have developed a high degree of grammatical complexity and elaborations without any help of written or visual translations of oral sounds.

5.There is also a sadness in recoginizing the diminishment of oral languages -- and with them the cultural legacies embodied in the oral performances. For members of an oral society to survive in the future, they must become literate -- and it then becomes even more important for literacy to restore memory and "to reconstruct for ourselves the pristine human consciousness which was not literate at all --at least to reconstruct this consciousness pretty well, though not perfectly... and bring a better understanding of what literacy has meant in shaping man's consciousness toward and in high-technological cultures."

Orality and Literacy, The Technologizing of the Word, Walter Ong, Routledge Press, 2002, Art: Ida

April 24, 2016

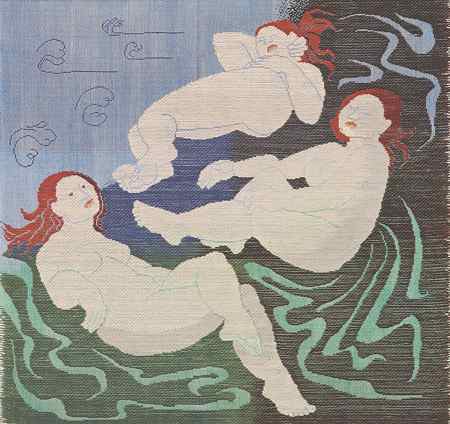

Slow Threads: The Beauty of Ethel Stein's Textile Art

Here is an inspiring short film on master weaver and artist Ethel Stein -- still working and creating textile art in her 90s. It is so inspiring to watch her moving slowly but with precision through the work of designing, warping, and planning out the complex pieces she creates. I also admire it because weaving takes time -- it is a slow, thoughtful process and one handles every thread -- multiple times -- before a work is even set up and ready to weave. I find myself more and more attracted to the idea of slowing the pace. I have finished, pretty much refurbishing my own loom (nothing so large as Stein's beauty) and I am just hoping to find some studio space this year to do some slow work myself.

Art: "Three Graces," Ethel Stein; Film Credits: Mark Chamberlain.

Midori Snyder's Blog

- Midori Snyder's profile

- 87 followers