Midori Snyder's Blog, page 24

August 10, 2017

Mountain Daughter and Wild Flower Children

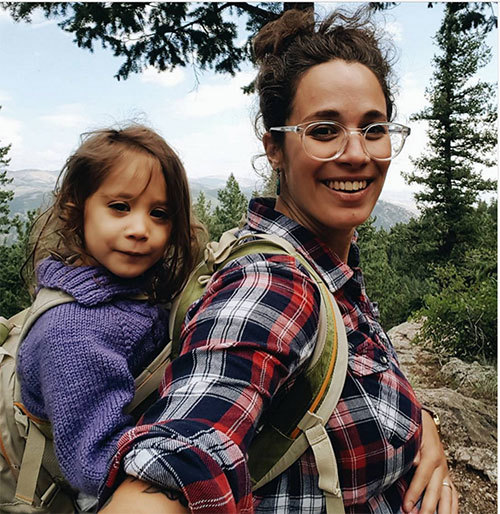

Congratulations to my mountain-daughter who was hiking yesterday high up in the Flat Irons of the Colorado Front Range, her two year old on her back and at 39 weeks pregnant. She came home, went into labor and delivered a beautiful baby boy, Luciano. All are healthy and happy. And I am a grandmother twice over now. So full of joy and love right now.

August 9, 2017

Bordertown Excerpt from WIP: Charon

���How much do you want for it?��� she asked.

���What do you have to barter?��� I said, knowing full well the answer. She was a halfling, pretty enough with one green and one yellow eye, a few years younger than me maybe. She was dressed in a blue hoodie, not made here, but crafted into something local with stitched birds and flowers covering the back. She had snagged me coming out of the Ferret, and as usual it was the top hat covered in soot that marked me. Now, here we were, squatted down in the alley behind the Ferret, the thump of music pushing out of the walls, negotiating a trade over something hard and hurtful.

���I don���t have much,��� she mumbled. I could tell the hand in her pocket was closed tightly around something, the last bit of value she had to give.

���Show it,��� I said.

She pulled her fist out and tossed the contents on the ground. By the light of the Ferret���s kitchen window, I saw how little it was, but I said nothing so as not to shame her. Broken bits of jewelry, a coin so rubbed down I couldn���t tell what it was, a few beads of swirled glass, and a hump-backed shell, speckled like an egg, with a row of teeth down the middle. My hand hovered over the shell and the girl flinched. I sure could trade that up, as cowries were as precious here as they had once been in the World.

It was tempting, but I moved my hand away and heard the sigh. I couldn���t take it from her, even if it meant I���d go hungry tonight. She���d already lost too much. Instead, I chose a silver ring that was missing its stone, and when I looked up, she gave me a weak smile.

���Where is she?��� I asked. The smile vanished.

���The old textile warehouse, off Soho. Second floor, back room.���

���How long has she been there?��� I stood, stuffing the ring in my pocket, wanting now to leave.

���I did what I could,��� she said, scrambling to gather her stuff and rise. She put a hand on my arm. ���Really I did. But she was already gone when I got there. So I don���t how long������

���Ok, I got it from here,��� I said and moved away from her. ���What���s her name?

���Fela,��� she whispered to the ground.

���Do you want a mori?���

���I got nothing to trade for that,��� she answered.

���On the house,��� I said. ���I���ll find you when its done and bring it to you so you don���t forget her.���

I walked away quick-like so I wouldn���t have to listen the sobs I knew were coming. I was used to that. Death never seemed as real to them as when our trade was concluded. A ring without a stone for a body without a life.

"Charon" �� 2017 Midori Snyder

What Cocteau Is Teaching Me About Writing

I am the sort of writer who likes to know the end of a story first, and have a narrative road map along the writing way. But I can't do that with this Bordertown story/novel/novellas? I have no idea yet how it will come together and I feel like Belle arriving at the Beast's castle, where the way is dark and perlious -- but those human arms holding up the candelabras, cast a small pool of light, leading to another pool of light, pushing her towards...what?

Another hallway, with huge windows and curtains blowing inward, the moonlight making stepping stones on the floor.

I think I am writing a Bordertown noir though I am still not sure how these separate stories will come together: a girl who either predicts or creates the future by painting grafitti on the walls, while her twin shifts the terminus stones beneath Bordertown to move it like a cosmic tortoise until one stone goes missing, threatening stability of the city; two gangs that come together to create their own martial arts with a unique Bordertown dojokun and plan a tournament of styles; an unknown girl found deceased in a warehouse, and the undertaker, himself a teenager trying to unravel her identity and return her to the right world. What sort of beast is waiting at the end of this story?

Ok...I think I am being waay too dramatic! I write moments, just let them happen, and then all day, they steep and somewhere in the middle of washing dishes, driving to the store, walking along the desert washes, or in these early pre-dawn mornings I keep, another candelabra lights up and I move in that direction. Good or bad, I have to trust that somewhere in my brain (or maybe my heart) that I already know the whole story.

August 8, 2017

Last Lines and Cool Captains

Near the end of the novel, The Pirates of the Levant by Arturo Perez-Reverte, Captain Alatriste finds himself the highest ranking survivor of one of three ships that are battling for their lives against the Turks, who out-gun, out-canon, and just sheer out number the Spaniards. There is a hasty meeting of the remaining "commanders" from the three ships, to determine whether they should surrender, or fight to an honorable death. One of the comanders is an aristocrat, and he wants surrender -- mostly because he knows he will be well treated and held for a high ransom. The rest -- will be slaughtered or suffer life as a chained galley slave. But the decision must be unanimous. Captain Alatriste, knows full well the horrors that would await them if they surrender, makes the only decision a seasoned soldier could make: fight to the end with honor. So we get this brief, sardonic moment:

"He was from the same caste of Spanish aristocrats, although this highly inelegant situation had tempered his arrogance--it's always best to talk to noblemen, Alatriste thought, when they've just been punched in the face..."

August 7, 2017

In Memory of My Mother: Tibetan A Ice Lhamo: The World Beneath the Tents by Jeanette Snyder

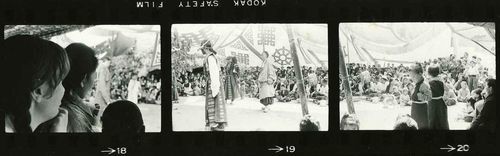

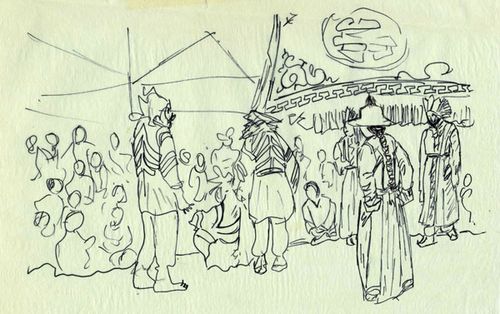

In 1964 my mother, Jeanette Snyder, then a graduate student in Tibetan Studies at the University of Washington, received a Fulbright Grant to study Tibetan theater in India, Nepal, and Sikkim, countries that had welcomed the flow of Tibetan exiles after the 1959 uprising. As a child, awaiting her return in the States, I loved her letters so full of fabulous descriptions of India and heroic, non���motherly sorts of adventures. During one of her visits, I asked her if she would recount for the blog her early experiences seeing Lha mo, the Tibetan opera she had come to study. What a pleasure it was to venture together into the basement, unpack the boxes of notes, field drawings, and photographs and listen to her recall her exhilaration at that first performance. While she took quite a few photographs, all I have of her at that event is this undeveloped image of at the far left, her turned away face, chin resting in her hand, and the sweep of her braid. I can tell she is smiling. So here is the article she wrote for Journal of Mythic Arts in 2005. ��� Midori Snyder

I sat in Glenary's Tea Room, dawn just breaking, wolfing down my substantial English breakfast in preparation for the day long event to come. Outside the window the trickle of Tibetans dressed in their best, carrying aluminum teapots filled with chang (beer), packets of snacks and lunch, cushions, umbrellas, babies on their back, toddlers in hand, and the occasional little dog tucked into the chest fold of a robe, had increased to a steady flow moving up along the high street beneath my window. I gulped down the last of my tea and grabbed my camera and tape recorder, eager to join the excited throng headed in the direction of the Darjeeling Tibetan School grounds.

The Himalayan Range was bright in the distance and the day promised to be fair. It was spring 1964 in Darjeeling, India, and I was on my way to experience my first live performance of A lce Lha mo or lha mo. The name lha mo is most commonly explained by Tibetans to have originated from the portrayal by actors of the many female roles of goddesses or "lhamo" that are found in the plays. A lce means "elder sister."....Read More > > >

**And here are two more posts with Jeanette's field drawings and notes.: Bittersweet Afternoon Under the Tent and More Field Drawings

August 6, 2017

Russian Collusion: "Charley's Away" in the Russian Translation of The Greenman Anthology

How wonderful is this -- and frankly, a wee bit strange to see my name in the Russian Cyrillic alphabet. This is the Russian translation of The Greenman Anthology, and I had to count the stories based on the US edition in the ToC inborder to be certain which one was mine! And what a lovely cover this is!

August 4, 2017

What Has Blogging Become in the Age of a "Like Button" and 140 Character Messaging?

I have been blogging at this location for the last ten years and it is with pleasure that I continue to so -- but perhaps with a much changed mission. When authors I know first started blogging, it was a way of communicating with people. I look back at the posts from five -six years ago, and I am surprised to see how many comments there are, sometimes a rich on-going discussion inspired by something in my post, or sometimes an exchange of very useful information. But such community is rare now on a blog. We have switched our allegiance to Facebook, where an announcement of a post does not actually mean someone will follow the link and read it, but they will express approval for the general idea by clicking the "like" button. And then we move even farther out, to a mere 140 characters in a tweet, to announce our blog post and receive a few "hearts" and maybe a re-tweet -- but still rare responses on the blog itself. Those kinds of conversations are pretty much over. And when I went down my list of bloggers, I was surprised to discover how many had packed it in for the nimble, quick-release variants of Facebook and twitter. And then there is Instagram, where the totality of an idea must be summed up in perfectly constructed images and hashtags.

Don't get me wrong -- I am not really complaining, just observing the transition and what it means for dinosaurs like me who still love to blog, even if it is for an audience of one. When I started blogging, I did so as a co-creator along with Terri Windling for the Journal of Mythic Arts and the Endicott Studio. We wanted to be a resource of myth, art, and folklore goodness. We wanted to share the wonderful work done by so many talented people. So the posts were always aimed outward. When we archived JoMA and the Endicott Studio, blogging finally shifted to the personal. I set up my own blog, In the Labyrinth in 2007 and shortly thereafter, Terri did the same.

And that was a profound shift -- from promoting others to promoting ourselves and our work -- and it took a while to figure that out. How much personal information to share, family photos, events, favorite meals -- all the early posts that now seem so much better suited for Facebook. And somewhere along the way, I also wanted to review books I loved, write short critical essays on literary culture, folklore, my own writing, and what inspired me. I am pretty eclectic, I know that -- a magpie who is happy to post on the intellectual roots of Garcia Lorca's "Duende" to theatrical work with trance-inducing masks, to Medieval bad-boy poets who wrote pornographic poetry, deconstructing a brilliant sentence from Conrad, Balzac's treaties on Coffee drinking (which bordered on the hallucinogenic), Russian artists, Medieval Manuscripts and Irish poets, and The Voynich Manuscript. I do try and promote my work by sharing my research notes and excerpts, my struggles sometimes with getting a story right, and the ever important announcement of a new title.

I understand that I am writing a journal, and that actually pleases me. I am less concerned with how far a post of mine travels, but rather that I can call up the evolution of my ideas over time -- a long time -- and revisit past ideas. A body of my own thought. But...in the interest of not feeling quite so lonely, I go every day now to other people's blogs that I find interesting and I make a point of responding to the post, to asking questions, sharing my own thoughts on the subject where appropriate. And I am planning once a week to share (on facebook of course!) the best of the blog posts for the week that I found, and encourage you if interested to visit them and respond.

Art credits: The inestimable Edward Hopper.

August 3, 2017

The Martial Life: Honor and Loyalty in Arturo P��rez-Reverte's The Pirates of the Levant.

There is a passage in Arturo P��rez-Reverte's The Pirates of the Levant that struck me as true. We are a military family and for over ten years it has been my pleasure (mingled with a mother's worry and sometimes grief at the violent deaths) of being in the company of remarkable men who have served or are still serving. I have met them at my local bar on occasion when they arrive in groups to attend jump school to sharpen their parachuting skills. And, with the slight cache of being a mother to one of them (even if he's not there), I am treated with affection and respect. They drink ��� lord how they drink ��� and gathered together in that small bar, they are both aware and oblivious of their alpha status, that other men not of their company stare at them with a mixture of resentment and awe. So, I was struck by the way P��rez-Reverte has captured so much of the uniqueness of a soldier's life in his novels; Captain Alatriste, with his cool green eyes, his slow to anger and quick to kill if challenged; his rules of honor that maintain a semblance of order and control in a world that is constantly engaged in war in the service of a conflicted royalty. Never paid what they are worth, these elite soldiers are yet keenly aware of their own self worth, their loyalty to each other, and their finely honed skills on which they survive.

The Captain Alatriste novels are a combination of storytelling and memoir; the first person narrator, I��igo Balboa recounts his life when, after the death of his father, he became the ward of Captain Alatriste, and later his education as a young boy into soldier, trying to emulate the life of his fallen father and earn the respect of his mentor and benefactor. At the same time I��igo recalls his life with Alatriste, he creates a second narrative in third person of the Captain's life, his adventures, the women who loved him and he they, and those of his fellow soldiers and enemies. It is a wonderful conceit for the reader gets a dual narrative ��� even though it's hard to know if we should entirely trust I��igo's version of Alatriste's life, colored as it is by his love and admiration for the Captain, whom he considers the epitome of a consummate and honorable solider.

So, here is the passage that rang in my head ��� having heard such a sentiment expressed among all those young men I know in that life now. Reflecting on the fates of his own father and other elderly soldiers, broken by old wounds and poverty, Ingio still believed at 17 years of age and having already served in two wars, that this is the only life for him.

"I was old enough and intelligent enough to recognize the ghost of my father in that remnant of a man, and sooner or later, in that of Captain Alatriste, Copons, and myself. None of this changed my intentions. I still wanted to be a soldier, but the fact that, after Oran, I wondered if it would not be wiser to think of military life as a means rather than as an end, as a useful way of confronting ��� sustained by the rigor of a discipline, a rule ��� a hostile world I did not yet know well, but which I sensed would require everything that the exercise of arms or its results could teach me. And by Christ, I was right. When it came to facing the hard times that came later, both for poor, unfortunate Spain, and for me, as regards to loves, absences, losses, and griefs, I was glad to be able to draw on it all of that experience. And even now, on this side of the frontier of time and life, having been certain things and ceased to be many more, I am proud to sum up my existence, and those of the loyal and valiant men I knew, in the word "solider." Even though, in time, I came to command a company and made my fortune and was appointed lieutenant and later captain of the King's guard ��� not a bad career, by God, for a Basque orphan from Onate ��� I nevertheless always signed any papers with the words Ensign Balboa ��� my humble rank on the nineteenth of May in sixteen hundred and forty-three, when, on the plains of the Rocroi, along with Captain Alatriste and what remained of the last company of Spanish infantry, I held aloft our old and tattered flag. "

All the photos are from the Spanish film "Captain Alatriste" with, yes, Viggo Mortenson as the Captain, giving his performance in Spanish. You can see quite a few clips on Youtube ��� including the harrowing final battle at the plains of Rocroi.

August 2, 2017

The Art of the Long Sentence: Arturo P��rez-Reverte

In the midst of reading The King's Gold, Arturo P��rez-Reverte's fourth volume in his swashbuckling series "The Adventures of Captain Alatriste," I came across one of those brilliant, long, elegant, artfully constructed sentences that takes up almost the entire paragraph. I've read it over several times and just can't get over how gorgeous it is. My editors would kill me if I attempted so ambitious a sentence -- mostly because I am completely comma dysfunctional, though I try very hard. The novel, set in 1626 Cadiz, Spain opens to the return of soldiers who have fought and survived the bloody seige of Breda, in Holland. It is a bustling port scene, with disembarked soldiers doing what they love best when finding themselves home and alive:

In the midst of reading The King's Gold, Arturo P��rez-Reverte's fourth volume in his swashbuckling series "The Adventures of Captain Alatriste," I came across one of those brilliant, long, elegant, artfully constructed sentences that takes up almost the entire paragraph. I've read it over several times and just can't get over how gorgeous it is. My editors would kill me if I attempted so ambitious a sentence -- mostly because I am completely comma dysfunctional, though I try very hard. The novel, set in 1626 Cadiz, Spain opens to the return of soldiers who have fought and survived the bloody seige of Breda, in Holland. It is a bustling port scene, with disembarked soldiers doing what they love best when finding themselves home and alive:

"When we said our goodbyes, Curro Garrote was already back on dry land, crouched beside a gaming table that guaranteed more tricks and surprises than spring itself, and playing cards as if his life depended on it, his doublet open and his one good hand resting, just in case, on the pommel of his dagger, while his other hand traveled back and forth between his mug of wine and his cards, which came and went accompanied by curses, oaths, and blasphemies, as he saw half the contents of his purse disappearing into someone else's."

There is so much happening here, and like the eye of a camera in an opening scene, it visually moves the reader from moment to moment in such a smooth, unbreakable line, so that we see both the details and the entire scene all together.

And again, this time in The Pirates of the Levant, the latest novel of Captain Alatriste, P��rez-Reverte's narrator provides an observation on the harsh life aboard a galley sailing to battle that mid-way draws the reader in with the switch in viewpoint -- from the "sailors" to "you" so that the reader must share personally in the discomfort.

And again, this time in The Pirates of the Levant, the latest novel of Captain Alatriste, P��rez-Reverte's narrator provides an observation on the harsh life aboard a galley sailing to battle that mid-way draws the reader in with the switch in viewpoint -- from the "sailors" to "you" so that the reader must share personally in the discomfort.

"Years before, he had found it difficult to adjust to the harsh galley life: the lack of space and privacy, the worm-and-mouse-eaten, hard-as-iron ship's biscuits, the muddy brackish water, the cries of the sailors and the smell of the galley men, the itch and discomfort of clothes washed in salt water, the restles sleep on a hard board with a shield as pillow, your body always exposed to the sun, the heat, the rain, and the damp, cold nights at sea, which could leave you either with congestion or deafness."

P��rez-Reverte also marries such remarkable descriptive and gritty sentences with small inserts of poetry -- written by some of the most famous poets of the age, viseral commentators on the excesses of their age, especially the seemingly never-ending wars. At the end of this detailed descriptive passage on military galleys, we are to be reminded by the 17th century poet Francisco de Quevedo of those who have it worst on the ships, the galley slaves who live chained to their oars.

"I'm a scholar in a sardine school,

And good for nothing but to row;

From prison I did graduate,

That university most low."

*Kudos should also got to Margret Jull Costa, the translator, who has enabled us to smoothly read such densely-packed sentences.

August 1, 2017

Reposting My Reviews of the Captain Alatriste Series by Arturo Perez-Reverte

**As I have been reading the last two novels in the Captain Alatriste Series by Arturo P��rez-Reverte, and really want to write more about them -- I thought it worth while to revisit two earlier posts (one from 2008 -- almost ten years ago! ) that provide both reviews of the earlier books and details on why I admire them so much. Here is the first:

It seems right on Veterans Day to review the swashbuckling and harrowing novels of the 17th century Spanish swordsman, veteran of the Thirty Years War, and sometime royal assassin, Captain Alatriste written by Arturo P��rez-Reverte. P��rez-Reverte deftly combines the heroic tale of a charismatic swordsman, a wry social history of a corrupt Spanish Empire, and a coming of age story for the novel's narrator, I��gio Balboa, the orphaned son of a fallen soldier now apprentice to Alatriste as a page.

And what a figure Captain Alatriste cuts throughout these novels: tall and slim, wrapped in his cape, with a sword and long dagger at his side, his face shadowed by the broad brim of a felt hat, an aquiline nose, huge mustache, and blazing eyes. "He was not the most honest or pious of men, but he was courageous...It was one of Diego Alatriste's virtues that he could make friends in Hell," I��gio tells us in the introduction. His title of Captain, more complimentary than official, was bestowed on him by the men who fought at his side one winter in Holland. His legendary skills with the sword have attracted the attention of the king, his scheming advisers, the Inquisition, and an Italian assassin with a score to settle.

And what a figure Captain Alatriste cuts throughout these novels: tall and slim, wrapped in his cape, with a sword and long dagger at his side, his face shadowed by the broad brim of a felt hat, an aquiline nose, huge mustache, and blazing eyes. "He was not the most honest or pious of men, but he was courageous...It was one of Diego Alatriste's virtues that he could make friends in Hell," I��gio tells us in the introduction. His title of Captain, more complimentary than official, was bestowed on him by the men who fought at his side one winter in Holland. His legendary skills with the sword have attracted the attention of the king, his scheming advisers, the Inquisition, and an Italian assassin with a score to settle.

Each novel centers on a different facet of Spain's history, offering in broad brush strokes a glimpse into the contradictions of the Glorious Empire. Captain Alatriste introduces us to the world of court intrigues, plots and counter plots, disguised kings, and the ability of a swordsman to make powerful enemies for following his own code of honor. Purity of Blood pits Alatriste and I��gio against the combined forces of the Inquisition and the royal advisers seeking to acquire the wealth and lands of prominent families.

Each novel centers on a different facet of Spain's history, offering in broad brush strokes a glimpse into the contradictions of the Glorious Empire. Captain Alatriste introduces us to the world of court intrigues, plots and counter plots, disguised kings, and the ability of a swordsman to make powerful enemies for following his own code of honor. Purity of Blood pits Alatriste and I��gio against the combined forces of the Inquisition and the royal advisers seeking to acquire the wealth and lands of prominent families.

The Sun Over Breda finds Alatriste and I��gio returned to the battlefields of Holland, where they survive the brutal seige at Breda and I��gio comes of age in the bloody fields of Holland. It is the most military of the three novels -- and certainly, the bloodiest. But it also reveals why the Spanish soldiers were the most feared across Europe -- even when they were half starved and abandoned by a King who took them for granted. The King's Gold returns them to Spain, veterans without work. Captain Alatriste is called upon to secretly steal a shipment of gold for the King that is being smuggled into the Spain by corrupt officials to the Crown. Perhaps one of the most interesting scenes of this novel takes place in Seville's prison -- where Alatriste spends a night celebrating the life of an infamous ruffian on the eve of his execution.

The novels also ground their stories in Spain's rich literary and artistic culture -- famous dueling poets of the time such as Don Francisco de Quevedo drink and fight alongside Alatriste, composing poems even as they are fighting. (An appendix at the end of the novels provides us with more poems from these well known authors of the time.) I��gio is reading Cervantes' Don Quixote as he is marching through the battlefields of Holland and later, he will try to give advice to the court painter Diego Vel��zquez, whose enormous painting "The Surrender at Breda" depicts more myth than fact.

The novels also ground their stories in Spain's rich literary and artistic culture -- famous dueling poets of the time such as Don Francisco de Quevedo drink and fight alongside Alatriste, composing poems even as they are fighting. (An appendix at the end of the novels provides us with more poems from these well known authors of the time.) I��gio is reading Cervantes' Don Quixote as he is marching through the battlefields of Holland and later, he will try to give advice to the court painter Diego Vel��zquez, whose enormous painting "The Surrender at Breda" depicts more myth than fact.

I��gio Balboa, the narrator, is a terrific voice in the novels. An old man, he is recounting his youth and apprenticeship with Alatriste, seasoned with witty, sardonic, and poignant observations of the decline of his once powerful nation. When he relates the battles of Breda he does so as a soldier in visceral, vivid language that is at once robust, filled with pride but tinged with melancholy at the enormity of the sacrifice: "And nine years later, in Madrid, standing before Diego Vel��zquez's panorama, it seemed I could hear again the drum and that I was watching, amid the forts and smoking trenches in the distance, near Breda, the slow advance of the old, implacable squads, the pikes and standards of what was the last and best infantry in the world: despised, cruel, arrogant Spaniards discipline only when under fire, who suffered everything in any assault but would allow no man to raise his voice to them."

I��gio Balboa, the narrator, is a terrific voice in the novels. An old man, he is recounting his youth and apprenticeship with Alatriste, seasoned with witty, sardonic, and poignant observations of the decline of his once powerful nation. When he relates the battles of Breda he does so as a soldier in visceral, vivid language that is at once robust, filled with pride but tinged with melancholy at the enormity of the sacrifice: "And nine years later, in Madrid, standing before Diego Vel��zquez's panorama, it seemed I could hear again the drum and that I was watching, amid the forts and smoking trenches in the distance, near Breda, the slow advance of the old, implacable squads, the pikes and standards of what was the last and best infantry in the world: despised, cruel, arrogant Spaniards discipline only when under fire, who suffered everything in any assault but would allow no man to raise his voice to them."

**A side note. In the original post, I was asked in the comments why I called the painting of "The Surrender at Breda" a myth -- so here is my answer:

It's actually the way it is presented in the novel -- the narrator as an eye witness to the Surrender at Breda is there to advise Velazquez on the veracity of his painting. But the artist at a certain point takes artistic license to create a dramatic image regardless of the truth (according to the narrator) of the event. Thus it's one of those moments in the novel where Perez Reverte is commenting on the distance between those in the battle and those who memorialize it as more romantic event. Most of that novel leading up to the battle is anything but romantic -- so at then end we have this odd flourish of art as the brutality of the event is contained with the painting. And because the painting becomes the last word for the public so to speak -- it creates a mythic image of the event.

Midori Snyder's Blog

- Midori Snyder's profile

- 87 followers