Nichole Bernier's Blog, page 2

March 28, 2018

Stepping up

While I was in Washington DC for the March for our Lives, this happened. Our foster cat had her babies. No matter that I’d spent the past week sleeping on an air mattress in her little room. This was her time, and it was going to come whether it was on my watch, or my reluctant anxious husband’s.

She delivered six healthy jet-black panther babies, a wiggling pile of midnight silkies. My husband and the older kids were the doulas, making sure each one was attended to by the mom, then weighing them and documenting their growth through the weekend.

When I came home, these new experts in feline midwifery introduced me to the kittens and schooled me in what’s best done around the protective mom.

Another reminder that when I step back they can step up, and it makes them that much more invested in the outcome.

Though it’s a lot easier to be invested in newborn bleating kittens than a load of laundry they’ve delivered from the dryer to the folded piles.

December 11, 2017

Deck the Halls and your brother

So Saturday night we had a very nearly Currier & Ives moment when after ordering in Chinese, all five went outside for an epic game of snowball hide-and-seek.

Tom & I sneaked out and launched a surprise attack from behind the grill, and all was feeling sort of kumbaya until the two who attack each other attacked each other.

There was the rubbing of faces into snow and ice and screaming and going to bed mad and oh well, Currier & Ives didn’t do take-out Chinese anyway.

October 24, 2017

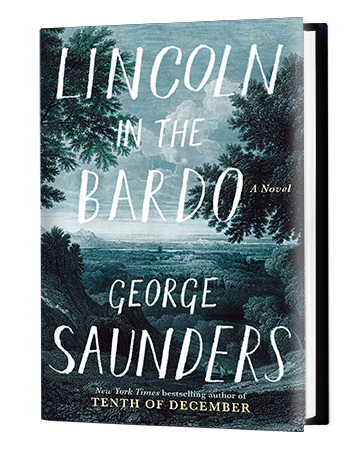

Booker-winner BARDO, odd and brilliant

I just finished the strange and un-put-downable LINCOLN IN THE BARDO, which won the Man Booker prize while I was reading it. Entirely deserving. It’s historical, biblical, Dantesque, supernatural, and just plain bizarrely unique.

It’s about the death of Lincoln’s son, a true kernel that spirals into a fable. Written like the script of a play, it’s told through a series of ghosts lamenting the lives they can’t let go, which keeps them rooted in a sort of purgatory. Lincoln suffers, and the boy is tethered to the father he loves. But it’s really about what matters most to us in life, how to live knowing it’ll end, and how to let it go. Not for the faint of heart.

October 20, 2017

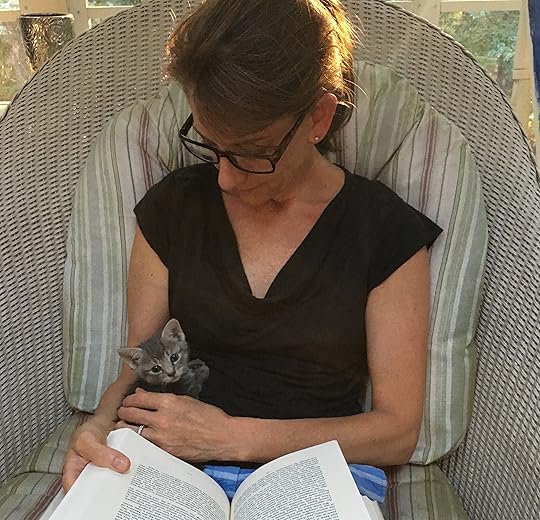

My study companion

Born at our house, going to their new families in a month. Already sad to let her go. I hope they appreciate what a literary soul she is.

Born at our house, going to their new families in a month. Already sad to let her go. I hope they appreciate what a literary soul she is.

October 3, 2017

When doing good doesn’t feel so great

In the latest litter we fostered there was a clear runt, a tiny watchful Yoda, all head and twitchy ears. She could run and jump and wrestle with the others, she just got tired more easily. After awhile she’d come back to sit on my lap while I typed, crouching on delicate paws and curling herself into a space the size of a child’s handprint.

In the latest litter we fostered there was a clear runt, a tiny watchful Yoda, all head and twitchy ears. She could run and jump and wrestle with the others, she just got tired more easily. After awhile she’d come back to sit on my lap while I typed, crouching on delicate paws and curling herself into a space the size of a child’s handprint.

Our job was to fatten her up like her three siblings. They’d all be adoptable in a month, as long as they reached two pounds. All four were eating canned food watered down to a gruel, and I’d been supplementing the littlest one’s diet with syringes of feline milk.

But it wasn’t enough. Yesterday morning she was lying on her side, immobile. I sped her to the vet wrapped in a blanket, but brought her home an hour later in a small box. When the kids came back from school I walked them to the tiny grave circled with stones. I explained “fading kitten syndrome,” the catch-all term used for the ones not robust enough to digest food well and fight germs.

The folks at the shelter where I foster say there’s one in every group; for each litter of, say, five kittens, about 3.5 make it to eight weeks old. But the statistics are lost on my younger boys. They had helped raise more than 10 litters and we’d never lost one. Standing under the tree looking down at the stone circle, that achievement seemed to wilt.

Why do it? I wondered, after we went back into the house to feed the remaining three. Really, why do it to ourselves? It’s nice to play a role in helping strays born in the bushes or pulled from horder homes become welll-socialized pets. And it’s certainly no hardship being able to play with these furry ping-pong balls for a few weeks. I’ve often felt like we had a secret; sshh, don’t tell anyone where they came from, or everyone would do it and there wouldn’t be enough for us. But even when it ends well, it ends sadly. I always have trouble saying goodbye.

Why do it? I wondered, after we went back into the house to feed the remaining three. Really, why do it to ourselves? It’s nice to play a role in helping strays born in the bushes or pulled from horder homes become welll-socialized pets. And it’s certainly no hardship being able to play with these furry ping-pong balls for a few weeks. I’ve often felt like we had a secret; sshh, don’t tell anyone where they came from, or everyone would do it and there wouldn’t be enough for us. But even when it ends well, it ends sadly. I always have trouble saying goodbye.

Then there are the times it isn’t going well — are they eating enough, do they have a respiratory infection, is the pinkeye getting better? And the inevitable math: For every one that’s rescued, there are probably two that aren’t. Which can make fostering feel like a zero-sum game. Holding a plush undersized creature taking its last breaths can make a person wonder whether they really want to be a part of it. The Humane Society estimates that tens of thousands of families foster pets every year; if I decided it was too raw for us, the shelter surely had other foster families who’d fill the gap.

That same morning, the news broke that a shooter in Las Vegas had killed 58 people and wounded 500 overnight. Mourning a kitten felt a little obscene against that backdrop of loss. Not to mention Puerto Rico, where 84 percent of the people still didn’t have power following Hurricane Maria, and 37 percent didn’t have clean water. It’s easy to let that zero-sum feeling leak through your firewalls and dampen your attitude, easy to feel ineffectual when a wave of bad news pummels one day, and then again the next. It erodes your sense that small things are worth doing, even if the small things are the only measure of difference in a zero-sum game.

and wounded 500 overnight. Mourning a kitten felt a little obscene against that backdrop of loss. Not to mention Puerto Rico, where 84 percent of the people still didn’t have power following Hurricane Maria, and 37 percent didn’t have clean water. It’s easy to let that zero-sum feeling leak through your firewalls and dampen your attitude, easy to feel ineffectual when a wave of bad news pummels one day, and then again the next. It erodes your sense that small things are worth doing, even if the small things are the only measure of difference in a zero-sum game.

And yet. Yesterday afternoon an email came from the new owner of Clyde and Flynn, two of the kittens from a litter born at our house in May. The boys are six months old and behave like drunken teens at a house party, and their new owner loves it.

One day I heard a strange creaking sound coming from the hallway, the woman who’d adopted them wrote in an email. There was a wooden clothes-drying rack and he’d climbed up and was and swinging from his front paws like a kid on a jungle gym. I’ve attached the video or you wouldn’t believe me. They are thriving, Nichole, and they just love people. I’m so fortunate that they had you and yours as their foster family.

October 2, 2017

Why do it

In the latest litter we fostered there was a clear runt, a tiny watchful Yoda old soul, all head and twitchy ears. Even though she was considerably smaller she could run and jump and wrestle with the others. She just got tired more easily. After awhile she’d come back to sit on my lap while I worked on my laptop, crouching on delicate paws and curling herself into a space the size of a child’s handprint.

In the latest litter we fostered there was a clear runt, a tiny watchful Yoda old soul, all head and twitchy ears. Even though she was considerably smaller she could run and jump and wrestle with the others. She just got tired more easily. After awhile she’d come back to sit on my lap while I worked on my laptop, crouching on delicate paws and curling herself into a space the size of a child’s handprint.

Our job was to fatten her up like her three siblings. They’d be adoptable in a month, as long as they reached two pounds. All four were eating canned food watered down to a gruel, but I’d been supplementing her diet with syringes of feline milk. “Yay, Peanut,” my eight-year-old would say when I worked the stream between her teeth and she got most down.

I’d been supplementing her diet with syringes of feline milk. “Yay, Peanut,” my eight-year-old would say when I worked the stream between her teeth and she got most down.

But it wasn’t enough. Yesterday morning she was unable to get up. I sped her to the vet wrapped in a blanket, but brought her home an hour later in a small box. When the kids came home from school I walked them to the tiny grave circled with stones. I explained “fading kitten syndrome,” the catch-all term used for the ones not robust enough to digest food well and fight germs.

For each litter of, say, five kittens, about 3.5 make it to eight weeks old. The folks at the shelter where I foster shake their heads, “there’s one in every group.” But the statistic was lost on my younger boys. They had helped raise more than 10 litters and we’d never lost one, not even the other runts. Standing under the tree looking down at the stone circle, that achievement seemed to wilt.

Why do it? I wondered, after we trudged back to the house and fed the remaining three. Really, why do it to ourselves? Set aside for a minute the altruistic pleasure of helping tiny kittens born under some bush, and raising them to be good companions. There is responsibility and worry — are they eating enough, do they have a respiratory infection, is the eye getting better? Even when it ends well, it ends sadly. I always have trouble saying goodbye.

People say you are so good, etc etc, but it doesn’t feel like anything noble. Honestly, we feel lucky to play with these furry ping-pong balls for a few weeks, watch them bounce around our rec room and collapse in a sleepy heap on our laps. I often felt like we had a secret; sshh, don’t tell anyone where they came from, or everyone would do it. The Humane Society estimates that tens of thousands of families foster pets every year. If we stopped fostering, if I decided it was too raw for us, the shelter surely had plenty of other foster families who’d fill the gap.

People say you are so good, etc etc, but it doesn’t feel like anything noble. Honestly, we feel lucky to play with these furry ping-pong balls for a few weeks, watch them bounce around our rec room and collapse in a sleepy heap on our laps. I often felt like we had a secret; sshh, don’t tell anyone where they came from, or everyone would do it. The Humane Society estimates that tens of thousands of families foster pets every year. If we stopped fostering, if I decided it was too raw for us, the shelter surely had plenty of other foster families who’d fill the gap.

And if they didn’t, what difference did it make, really? There are so many castoff animals in this overpopulated world of strays and storms and hoarder homes. For every one that’s rescued, there are two that aren’t, and another two pulled from a bad place but not getting adopted. Sometimes fostering cam feel like a zero-sum game. And yesterday morning, holding a plush undersized creature taking its last breaths, can make a person wonder whether they really want to be a part of it.

That same morning, Boston woke to the news that a shooter in Las Vegas killed 58 people and wounded 500, and mourning a kitten felt a little obscene. In Puerto Rico, 84 percent of the people still didn’t have power following Hurricane Maria, and 37 percent didn’t have clean water. It’s easy to feel ineffectual when a wave of bad news pummels one day, and then again the next. It erodes your sense that small things are worth doing, even if the small things are the only measure of difference in a zero-sum game.

and wounded 500, and mourning a kitten felt a little obscene. In Puerto Rico, 84 percent of the people still didn’t have power following Hurricane Maria, and 37 percent didn’t have clean water. It’s easy to feel ineffectual when a wave of bad news pummels one day, and then again the next. It erodes your sense that small things are worth doing, even if the small things are the only measure of difference in a zero-sum game.

Yesterday afternoon an email came from the new owner of Clyde and Flynn, two of the kittens from a litter in May. The boys are six months old and behave like drunken teens at a house party, and their new owner loves it.

Flynn likes to jump so I need to keep my eyes on him, wrote the new owner Nancy, who’d lost her longtime cat a few months before. His recent discovery is jumping on the dining room table and standing up to hit the chandelier and make it sway. One day I heard a strange creaking sound coming from the hallway. There was a wooden clothes-drying rack and he’d climbed up and was and swinging from his front paws like a kid on a jungle gym. I’ve attached the video or you wouldn’t believe me… They are thriving, Nichole, and they just love people. I’m so fortunate that they had you and yours as their foster family.

August 18, 2017

Locker room talk when you’re 7, 9, and 11

Overheard from the hall outside the younger boys’ bedroom after lights-out:

Overheard from the hall outside the younger boys’ bedroom after lights-out:

“Did you know that every 20 minutes a new batch of boogers grows in your nose? True story.”

July 30, 2017

There be monsters and other wishlist travel

Over summer vacation my kids were addicted to RIVER MONSTERS, the extreme fishing adventure series on Animal Planet. Jeremy Wade’s silky British accent was the soundtrack of our rental house. Mysterious fish were killing kayakers on the Amazon, spearfishermen disappearing in Malaysia. Wade spoke of the murderous creatures with awe, almost affection. Early mornings before the beach and evenings while we fired up the grill, there was Wade, with his white hair and weather-beaten face, like a distant uncle who’d dropped in on our family vacation.

Early one morning before the rest of the family was up, I sat on the couch with my 8- and 9-year-olds.

“I’m in Argentina…. A 12-year-old girl was playing close to her village on one of the remote islands set in this huge river. She had entered the water countless times before, but this time it would be different. This time there was something waiting in the shallows.”

It’s easy to see why my boys were transfixed. The patterns of the rollout was irresistible. The thrill of the predatory unknown. The cliffhanger commercial breaks with a thrash and swoosh of bloodied water. And then finally the creatures themselves, all jaws and teeth, menacing and otherworldly as bulky-headed aliens.

predatory unknown. The cliffhanger commercial breaks with a thrash and swoosh of bloodied water. And then finally the creatures themselves, all jaws and teeth, menacing and otherworldly as bulky-headed aliens.

It was especially potent for my 9yo, old enough not to be terrified, and young enough to see the expedition life as something entirely possible. Earlier in the summer he’d built himself a boat out of empty Poland Springs bottles and hockey tape. No matter that the Malaysian spearfish would slash it into BPA confetti. For propulsion, he would use a leaf blower. If he needed a turbo surge, he’d attach shaken-up cans of seltzer.

It was potent for me, too, but for different reasons — the cinematography, the exotic locales, the wide expanses of ocean and ice. The freedom to pursue a curiosity, get up and follow it across the planet. In the morning he’d take me to Greenland in a dogsled, and by dinnertime, a volcano in Iceland. Episode after episode was a parade of places I’d never been, but in my parallel life might have gone.

When I was in my mid-20s I worked at a glossy travel magazine. I had more journalistic assignments than exotic features, but there was travel—places like Prague and Nevis, Phoenix and Whistler. There was one dicey experience skiing in Taos, and a risky but fascinating investigation of Caribbean islands following a hurricane. After I left New York (married, baby), I stayed on as a contributing editor and an occasional tv commentator. Which is how I found myself as a mother of a toddler with the unlikeliest opportunity: to host a travel documentary. The magazine was doing a series, and the editor asked if I would narrate the story behind the stories.

Looking back now it seems like a fever dream. The details weren’t fully fleshed out, but it would entail being on location somewhere for about a week each month. I don’t remember determining with my husband how this would make sense with our one-year-old, though he says we did. Shortly after I said I’d do it, I found out I was pregnant with our second child, and the fever broke.

Travel is simpler these days. Weddings and family reunions, college tours and summers around New  England. But Airbnb.com is my late-night Netflix, and when I get itchy for new experiences, I curate wish lists of different kinds of adventures in the future: A lighthouse stay with my husband. A converted silo with a few of the kids, or farm stays with all of them. The writing getaways — an airstream in Montana, a treehouse in Bali, a whitewashed cave house on the Santorini cliffs. There’s a through-the-looking-glass quality to my life on AirBnB. Also, of a kid with her nose to the candy store window.

England. But Airbnb.com is my late-night Netflix, and when I get itchy for new experiences, I curate wish lists of different kinds of adventures in the future: A lighthouse stay with my husband. A converted silo with a few of the kids, or farm stays with all of them. The writing getaways — an airstream in Montana, a treehouse in Bali, a whitewashed cave house on the Santorini cliffs. There’s a through-the-looking-glass quality to my life on AirBnB. Also, of a kid with her nose to the candy store window.

During a RIVER MONSTERS commercial break my son said, “I’m going to do this. This is going to be my job. ” And why not? He likes nature documentaries, loves fishing. I Googled Jeremy Wade’s background. He studied zoology. He was a teacher. “You could totally do this,” I agreed.

Clicking around a bit more, I found out the episode we were watching was actually the final one of the entire series. After nine seasons, it had just gone off the air. Goodbye Wade, goodbye zodiacs flitting among the ice floes.

My son was disappointed, and I was, too. I don’t watch much TV, but this was different than the shows I remembered. Wade spoke to the audience like colleagues, partners in his discovery. The plot unfurled slowly with intelligent suspense, a puzzle wrapped in an expedition. He met the local people and experienced their cultures, and invited the viewer in along the way. In the end, it was more about the journey than the big reveal.

My son wanted to know if he was going to do another series. I searched a bit but didn’t see anything concrete. Plans for more television work, but Wade also hoped to pursue writing. Most of the interviews were vague, but in one, Wade expressed curiosity about the more psychological aspect of travel and distant cultures, something about the passage of time, nature and aging. I envisioned something like Ann Patchett’s novel State of Wonder, if it were reimagined by the Discovery Channel. Oh, my.

But my son, he was lost at psychological. All he heard was blah blah blah, no monsters. “Oh well,” he said, and drifted off to the kitchen.

But I went back to Google and set an alert to mentions of Jeremy Wade. I want to keep an eye on what he might do next, this television traveler with his compass set to my kind of shores.

July 2, 2017

Locker room talk when you’re 7, 9, and 11

Overheard from the hall outside the younger boys’ bedroom tonight after lights-out:

“Did you know that every 20 minutes a new batch of boogers grows in your nose? True story.”

June 16, 2017

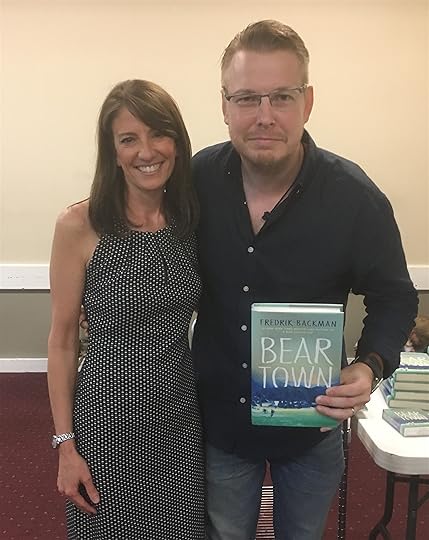

Interviewing Fredrik Backman

I love when the local bookstore asks me to interview a visiting author, to turn it into a Q&A style event. I like those kind of events when I’m doing readings myself, too; there can be more of a spark in a conversation than in a monologue. I think that’s why the questions at the end of a reading — unscripted, candid — is often the best part.

I love when the local bookstore asks me to interview a visiting author, to turn it into a Q&A style event. I like those kind of events when I’m doing readings myself, too; there can be more of a spark in a conversation than in a monologue. I think that’s why the questions at the end of a reading — unscripted, candid — is often the best part.

Yesterday bestselling Swedish author Fredrik Backman came to town, his only stop in the Boston area. I had three months’ notice to read his latest book, BEARTOWN, plus his backlist: A MAN CALLED OVE (once and for all settling any debate that existed over the pronunciation — it’s Ooo-veh), MY GRANDMOTHER ASKED ME TO TELL YOU SHE’S SORRY, BRITT MARIE WAS HERE).

I especially enjoyed BEARTOWN, about the effect of rabid youth hockey on a small town. It was darker than his earlier books, and questions the pack mentality of a team, and the way loyalties divide the community when one member is accused of a crime.

Interestingly, the main character is the town itself; the narrative lens is like a camera suspended above it, dipping in and out of each house, observing how the residents respond to the crisis. There is hand-wringing about what’s happening to the community and how the community can do this, which sounds eerily familiar in 2017 U.S. Backman doesn’t let individual responsibility off the hook: “Community is the sum of moral decisions made by the people who live there.”