Mariann S. Regan's Blog, page 2

January 27, 2013

Leaving Ireland to Grow Rice with Slaves. Part 1 of 2.

As I trolled for hints on Ancestry.com, I found this line about my 9 x g grandfather, Jonas Lynch (1650-1691):

“Imigrated [sic] Developed Rice Cultivation, Ireland.”

I had unlikely visions of some mad experimenting ancestor, with seeds and homemade sunlight deflectors, obsessing about rice 300+ years ago in the Emerald Isle.

“I’m about to Google rice cultivation in Ireland,” I told my husband, who is used to hearing the crazy twists of genealogical research.

He looked up at me. “If you do that,” he predicted, “they’ll reply, How stupid do you think we are here at Google?”

Well, I did find a cute website that patiently explained to me: Rice is not a potato, and rice is not grown in Ireland.

Never mind. When Jonas Lynch arrived in South Carolina from Ireland in the 1670s, he and others did plan to cultivate rice there.

I wish I could make visible onscreen, at a glance, the long family tree branch leading from me back to Jonas Lynch. Andy Kubrin in his thoughtful blog (check it out) discusses presenting a readable family tree onscreen, in some detail. I like that idea. Diagrams of others’ family trees would help me to read their blogs.

So why did Jonas leave Ireland? He and other Galway Lynches were expelled from Ireland because they had been defeated in the Irish wars between Jacobites and Williamites. Jacobites supported Catholic James II of England and Williamites supported Protestant William of Orange. The wars of that decade—involving the Dutch, French, English, Scots, and Irish—are complex enough to baffle anyone. Eventually, though, William III took the English throne in the Glorious Revolution of 1688. He and his wife Mary II ruled as joint monarchs.

Charles Towne Landing from http://indigoblue.sc

Jonas Lynch arrived on the South Carolina coast near Charles Towne “before Apr 30, 1677.” He is listed as a Gentleman, Esquire, and a Justice of the Peace. The record appears to quote his statement about his destination: “of Wattesaw als the blessing.” (1) These words made no sense to me until I found this entry in a local history:

BLESSING, THE – This former RICE plantation on the east shore of the Cooper River’s EAST BRANCH was first granted to colonist Jonah LYNCH in 1682, at a“place called Wattesaw also the Blessing.” WATTESAW was the Native American word for the area, meaning unknown. . . . It is presumed that the name “Blessing” came from the ship of the same name that brought Jonah Lynch to the colonies in 1671. (2)

When Jonah arrived, “The Blessing” meant simply the property he had been granted, 780 acres. Today there is a plantation house there on the Cooper River, called The Blessing:

Blessing Plantation House. South Carolina Department of Archives and History

A blessing for some was a curse for others. The land of opportunity for a few white families in South Carolina became the land of enslavement for multitudes from Africa.

Those European settlers were serious about their rice cultivation plans. There was even an experimenter with seeds, though it wasn’t my ancestor:

The first recorded effort at rice cultivation was conducted by Dr. Henry Woodward. . . . in 1685. Dr. Woodward obtained the rice seed from Captain John Thurber, who had sailed his ship to Charleston from the island of Madagascar. . . . [website]

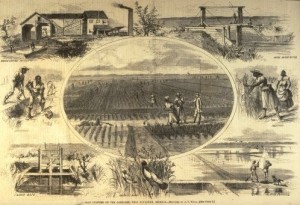

Yet the white planters of Charles Towne, Jonas Lynch among them, realized how little they knew about growing rice. They needed African slaves to teach them, and it took them years—past Jonas’s lifetime—to get rice cultivation up to speed.

The planters’] early experiments . . . were mostly failures. They soon recognized the advantage of importing slaves from the traditional rice-growing region of West Africa. . . . [They] were willing to pay higher prices for slaves from the “Rice Coast,” the “Windward Coast,” the “Gambia” and “Sierra-Leon”; and slave traders in Africa soon learned that South Carolina was an especially profitable market for slaves from those areas. . . . [They] ultimately adopted a system of rice cultivation that drew heavily on the labor patterns and technical knowledge of their African slaves. (3)

Under the duress of chattel slavery, these slaves contributed the knowledge and labor that made Carolina rich. Barbados had already demonstrated to the world, since the 1640s, that slave labor enforced by violence could bring great wealth.

Rice Cultivation in the South. cocinadeglo.blogspot.com

As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master. – Abraham Lincoln

Coverage of President Obama’s Second Inaugural Address, a few days ago, has often included this passage from Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, addressed to the crowd in 1963:

[M]any of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny and their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone.

The “destiny” part of this statement has been ironically true since the 1600s, when chattel slaves in South Carolina began teaching white planters how to grow rice. But what about the reciprocal and interwoven “freedom” between races? As a country, we’re still trying to figure that one out.

Next week: Jonah’s son, Thomas Lynch. Rice plantations flourish, and slaves increase in number.

Notes:

(1) Agnes Leland Baldwin, First Settlers of South Carolina, 1670-1680. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1969.

(2) Suzannah Smith Miles, East Cooper Gazetteer: History of Mount Pleasant, Sullivan’s Island, and Isle of Palms. History Press: May 2005. 26-27.

(3) Joseph A. Opala, The Gullah: Rice, Slavery, and the Sierra Leone-American Connection.

January 22, 2013

Ancestors, Land, the British Empire, and Slaves. Part 2.

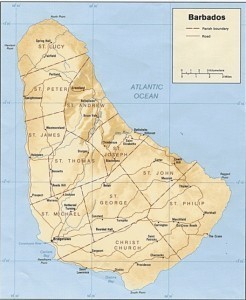

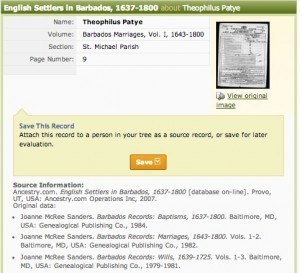

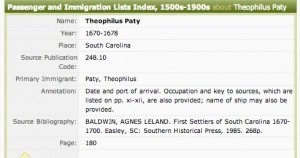

English settlers arrived at the eastern Caribbean island of Barbados in the 1620s, as early settlers of the infant British Empire. In 1656, my 9 x great grandmother and grandfather, Elizabeth Baker and Theophilus Patey, were married there. He was about 23, she about 20.

The colonists in Barbados were also virtually “in” England—politically.

In fact, the brief civil war in Barbados, in 1650-51, echoed the English civil war of 1649-60. What was the fighting about? Slavery (in metaphor), freedom, and the rights of Englishmen.

The Parliament Building in Barbados. Photo credit: Wikipedia

Let’s make a long story short here. A fierce debate about government was playing out in England, with bloody outcomes. Here’s an easy outline:

James I (1603-1625)

Charles I (1625-1649)

Rump Parliament, Oliver then Richard Cromwell as Lord Protector (1649-1659)

Charles II (1660-1685)

James II (1685-1688)

Notice: Two kings, then a no-king period from 1649 to 1660, then two more kings.

Parliament debated extensively, for years, about whether Charles I was acting too much like a tyrant. In 1649 a Rump Parliament led a High Court of Justice to convict Charles I of “treason.” Charles was beheaded on a scaffold in Whitehall, and the office of King was formally abolished.

England had killed its king. A dreaded taboo had been broken (as in Shakespeare plays like Hamlet, Macbeth, and Lear). Oliver Cromwell, a staunch Puritan with an Army, now ruled England. He finally dissolved Parliament and set himself up as Lord Protector. When he died in 1658, his son Richard couldn’t sustain the Protectorate.

So Charles II (son of Charles I) restored the office of King in1660 when he returned from exile and took the throne. Oliver Cromwell’s body was exhumed from its place in Westminster Abbey, decapitated, and buried in a common pit.

These events sharply polarized Englishmen. The Royalists (Cavaliers) believed in monarchy. The Parliamentarians (Roundheads) believed in Parliament and Cromwell, more or less. These divisions could have bloody consequences.

And this polarization crossed the Atlantic.

The white planters in Barbados knew their political differences as Royalists vs. Parliamentarians. Yet they agreed to suspend all disputes, because as a group they were busy growing rich by cultivating sugar with slave labor.

This political calm lasted until King Charles I was beheaded in 1649. Then the Royalists in Barbados grew angry. Soon, three more events stoked the flame.

In 1650 Charles II-to-be, from exile, sent Lord Willoughby, the Earl of Carlisle, overseas to govern Barbados. It was a Royalist “strike.”

Right away, Parliament struck back. It forbade Barbados to trade with Dutch ships (the ones that supplied African slaves). Royalists in Barbados could now convince their Parliamentarian fellow planters that Cromwell was out to destroy their sugar trade.

Finally, the Commonwealth of England in 1651, under Cromwell, sent an invasion force to Barbados—a fleet and an army, to force all English planters to knuckle under to the current government.

Well, nobody expected the Royal Navy. Not even the Barbadians.

Lord Nelson (1758-1805), consummate hero of The Royal Navy, in National Heroes Square in Barbados. photo credit: Wikipedia

While waiting for the invasion force, the white planters in Barbados met with their Royalist Governor (sent by the exiled Charles II). They were fired up to “defend themselves against the slavery that is intended to be imposed on them.” [my italics]

Theophilus would have been 18, old enough to bear arms, and Elizabeth a few years younger. They would both have been able to recognize the vast difference between the slavery of Africans on the sugar plantations and the “slavery” their own class feared from Cromwell’s tyranny. I imagine they carried this lesson with them to Charles Town in Carolina in the 1670s.

The planters issued a proclamation to the English Parliament on 18 Feb 1651, embracing to the death their principles of freedom and courage.(1) Its purpose was:

To announce to the inhabitants of Barbados that they “would be brought into contempt and slavery, if the same (Cromwell’s invasion) be not timely prevented,” and

To resolve that Barbadians will not “prostitute our freedom and privileges to which we are borne, to the will and opinion of any one; neither do we thinke our number so contemptible, nor our resolution so weake, to be forced or persuaded to so ignoble a submission, and we cannot think that there are those amongst us, who are soe simple, and so unworthily minded, that they would not rather chuse a noble death, then forsake their ould liberties and privileges.”

The rhetorical bedrock here is the language of liberty vs. slavery. In this way, the planters resemble the writers of our Declaration of Independence. Neither group focuses on the enslavement of Africans.

The colonists of Barbados put up a stiff resistance, and a hundred of them died in the first battle. It wasn’t long before the invasion leader turned the allegiance of the island’s Parliamentarians against its Royalists. The 1652 Charter of Barbados set mild conditions of surrender, with all rebellion forgiven and all lands restored.

The Charter allowed “that all trade be free with all nations that do trade and are in amity with England.” This suggests to me that the Triangle Trade was restored to Barbados, despite the Anglo-Dutch war (1652-1654).

Soon, Barbados was stable enough that young Theophilus Patey and Elizabeth Baker could be married at St. Michael’s Parish in 1656 and start a family on the island.

Barbados. St. Michaels in the southwest of the Island.

By 1660, the white planters of Barbados were back in business with as much trade, and as many slaves, as they had ever had. Or more.

Notes:

(1) Dr. Karl Watson writes, “It is interesting to note that in almost every warning or advisory issued by the Barbadians, slavery was used as a metaphor for the political control which England wished to establish over the island. It is more than ironic that the political directorate of an island, whose economy depended on slavery and the majority of whose population were slaves, should have used this institution as a rallying call for freedom for themselves.”

January 16, 2013

Ancestors, Land, the British Empire, and Slaves. Part 1.

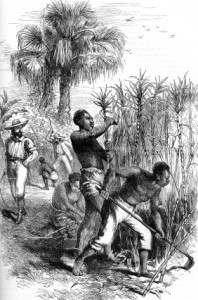

Hello to my 9 x great grandfather, Theophilus Patey. In 1656, he was getting married to my 9 x great grandmother Elizabeth Baker. They were on the small (21 x 14 miles) eastern Caribbean island of Barbados, in St. Michael’s Parish.

Marriage in an Anglican Church

He was probably 23, and she was about 20. Both had recently come from England.

Elizabeth Baker is Christened

They soon had eight children. Yet with the high disease and mortality rate on the island, five of their children died very young. Three other children survived. Finally, in the 1670s, the family moved to Charles Town, in the province of Carolina. Their most long-lived daughter, Elizabeth Patey, married Major John Boone, who founded Boone Hall Plantation on the 470 South Carolina acres given him by Theophilus Patey. (See my post of January 8, 2013).

Theophilus and Elizabeth were probably among those “good families” and “well-to-do Royalists” who were given land in the new colony of Barbados. Glancing at their ancestors, I’ve found one “Sir” and one “Lady.” Early English settlers like these, with “good financial backgrounds and social connections in England,” embody the British Empire beginning to take shape.

In those early years, the island of Barbados was free for the taking. King James claimed it in 1625, and the first settlers arrive in 1627. There were 80 settlers on that first ship, including 10 slaves. These slaves may have been “kidnapped or runaway English or Irish youth,” or they may have been African slaves. The Barbados settlement was financed by a London merchant who held the title to this island and two others, with the blessing of the Crown.

The Barbados economy, along with its slave population, rocketed upwards in the 1640s. That’s when the Sephardic Jews in Dutch Brazil taught Barbados planters how to cultivate sugar cane, and the Dutch slave traders began to sell them both equipment and African slaves. These slaves often died from bad conditions, overwork, and a climate of disease in Barbados. Yet Dutch ships could always replenish the slave supply. Later, whites from Britain and Ireland were also transported to Barbados, as indentured servants or prisoners, for heavy labor.

Slaves on a Sugar Plantation, with Overseer

So Barbados struck it rich, and that London merchant shared in the profits. With no labor shortage, and with a Triangle Trade that guaranteed them slaves and a market for their sugar, Barbados had more trade by 1660 than all other English colonies combined.

Yet a few dominant white planters began to consolidate all that wealth. And gradually, other whites, depressed by their declining income and fearful of slave uprisings (three uprisings failed in the 1600s), began to leave the island. Slaves from Africa kept coming, though. In 1644 Barbados had about 22,000 whites and 800 Africans. By 1700 there were about 15,000 whites and 50,000 Africans. My ancestors Theophilus and Elizabeth took part in this exodus, leaving between 1670 and 1678.

Theophilus Patey arrives in South Carolina

Whites moved from Barbados to Virginia, Georgia, the Carolinas, and the entire east coast of North America in the 1600s and 1700s, so that many people can trace their ancestors to Barbados.

Part 2 Next Week: Civil War in England comes to Barbados.

January 9, 2013

Two Surprises, and Nominations Paid Forward

Cheers for the Community of Geneabloggers! Cheers all round!

This afternoon, Wednesday, January 9th, I received two wonderful surprises.

First, Jana Last of Jana’s Genealogy and Family History Blog nominated my blog for the Wonderful Team Member Readership Award. Here is the award logo:

Those who created this award wrote, “As bloggers, we are also readers. That is a part of blogging as listening is a part of speaking.”

Jana, thank you. I feel privileged and grateful to receive this nomination. Your blog about your ancestors’ travels in America, with its stories and detailed work with photos, is always a delight to read.

Those bloggers nominated for awards are expected to “pay the honor forward.” So I will. Here are the rules we’re all supposed to follow:

(i) Don’t forget to thank the nominator and link back to their site as well;

(ii) Display the award logo on your blog;

(iii) Nominate no more than fourteen readers of your blog you appreciate and leave a comment on their blogs to let them know about the award;

(iv) Finish this sentence: “A great reader is…”

A great reader is someone who generously shares her/his own feelings, thoughts, and life experiences in response to what the blogger has written.

These bloggers have regularly commented on my blog with intelligence and kindness:

Liv Taylor-Harris at Claiming Kin

Shelley Bishop at A Sense of Family

Cheri Hudson Passey at Carolina Girl Genealogy

Jacqi Stevens at A Family Tapestry

Cindy Freed of Genealogy Circle

Those responders not nominated (on this round)—have also been extremely thoughtful in comments on my blog. I read all your comments carefully, and I reply with appreciation. In turn, I enjoy your blogs. Like Jana Last, I feel anguish because I so much regret leaving out any of you—that’s the anxious side of nominations.

A few hours after Jana’s nomination, I received a second surprise. Jen Baldwin at Ancestral Breezes nominated my blog for the Blog of the Year 2012 award, which has this website and this logo: It is humbling to be chosen by Jen Baldwin. Through her blog, she is a model of careful research priorities, initiative, unceasing diligence, and passion for genealogical work. I admire her greatly.

It is humbling to be chosen by Jen Baldwin. Through her blog, she is a model of careful research priorities, initiative, unceasing diligence, and passion for genealogical work. I admire her greatly.

Now I will “pay the honor forward” according to the rules for this award:

1 Select the blog(s) you think deserve the ‘Blog of the Year 2012’ Award

2 Write a blog post and tell us about the blog(s) you have chosen – there’s no minimum or maximum number of blogs required – and ‘present’ them with their award.

3 Please include a link back to this page ‘Blog of the Year 2012’ Award –http://thethoughtpalette.co.uk/our-awards/blog-of-the-year-2012-award/ and include these ‘rules’ in your post (please don’t alter the rules or the badges!)

4 Let the blog(s) you have chosen know that you have given them this award and share the ‘rules’ with them

5 You can now also join our Facebook group – click ‘like’ on this page ‘Blog of the Year 2012’ Award Facebook group and then you can share your blog with an even wider audience

6 As a winner of the award – please add a link back to the blog that presented you with the award – and then proudly display the award on your blog and sidebar … and start collecting stars…

With so many deserving blogs out there in the community of geneabloggers, it is painful to choose. But remembering that there will be other rounds of prizes, I will choose these for now, as blogs that are often moving, amusing, or teeming with research and advice:

Laura Lorenzana at The Last Leaf on This Branch

Stephanie Pitcher Fishman at Corn and Cotton Genealogy

Heather Wilkinson Rojo at Nutfield Genealogy

Angela Walton-Raji at

Kathleen Brandt at a3Genealogy

Caroline Pointer at 4 Your Family Story

Lynn Palermo at The Armchair Genealogist

Many thanks and kudos to everyone in the community of geneabloggers! In the months I’ve been among you, I have found a large group of smart, witty, friendly people. It is a splendid “family” group to belong to. There is so much kindness here, and so much dedication to family history research.

January 7, 2013

Berries and Thorns. Plantations and Slavery.

This is Boone Hall Plantation in 1940. Two rows of live oak trees shade the long entrance drive, and the main house and slave cabins are visible in the distance. Today Boone Hall stands as a prosperous and lively tourist attraction near Mount Pleasant, South Carolina.

Boone Hall Quarters, Library of Congress, photographer C. O. Greene, HABSHAER collection, April 8, 1940

Boone Hall is listed in the National Register of Historic Places and in the African American Historic Places in South Carolina. The website calls it “America’s Most Photographed Plantation.” You may have noticed Boone Hall in TV or film (The Notebook, for example).

Today it is still a working plantation, growing crops for sale and sponsoring annual events like the Lowcountry Strawberry Festival. The plantation’s Black History in America exhibit, open year-round, impressed Joseph McGill last November when he spent two nights in an original slave cabin at Boone Hall during his admirable Slave Dwelling Project . McGill’s full and nuanced account is here.

Boone Hall Plantation seems to be our country’s icon of the Southern plantation ideal. People love to visit it, take the tours, buy photographs, and even get married there.

Last week, I was astonished to discover Boone Hall Plantation in my own family history.

I was working my way up my matrilineal family tree, through Thomas Boone IV to Thomas Boone I (1696-1749), when I came upon Major John Boone (1632?-1711). The Major appears to have been my 7 x great grandfather. He was the founder of Boone Hall. His son Thomas Boone I, my 6 x great grandfather, planted those live oak trees that shade the three-quarter mile entrance drive.

What splendid, gracious beauty shines from Boone Hall. Like luscious berries.

What a vexed and painful history underlies the institution of American slavery, which gave birth to plantations like this one. A history lacerated with thorns.

My research tells me, so far, that Major John Boone may have been a rough customer. He seems to have been neither intimidated by regulations nor alarmed by the inhumane practices of the British slave trade. He was busy making money.

One source writes of Boone: “He was an Indian trader, slave dealer and fence for pirates sailing off the coast of South Carolina. He was commissioned by the Lords Proprietors to settle disputes with the Indians. John was elected to the Grand Council during the 1680’s but was removed twice because he illegally dealt in Indian slaves, associated with pirates and concealed stolen goods. He was later reelected by Parliament” (1).

A Boone family web page, studded with historical and parish records, claims that John Boone is the son of a butcher and barber in Devonshire. He emigrated initially as “a servant . . . an ambitious man” who “became a successful merchant (if by some unsavory businesses) and married into another monied Carolina family.”

Other sources suggest that as a First Fleet settler of South Carolina, arriving perhaps from Devon, Somerset around 1670 (2), John Boone got a series of land grants from the state’s Lords Proprietors. With one of these grants he founded Boone Hall on 470 acres given him by Theophilus Patey (3), who would become his father-in-law.

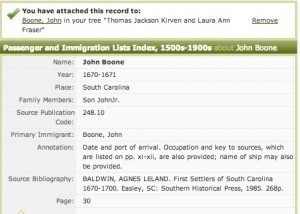

John Boone arrives in South Carolina?

John Boone obviously prospered. He was apparently accepted into the church, the army, and the government by his fellow colonial settlers. He was a Major in the colonial militia. He was chosen as one of seven vestrymen for Christ Church Parish, whose ministers were expected to convert infidels, Indians, and slaves (4). He was elected to the Grand Council, then removed, but reelected by Parliament. It seems that in these times and circumstances (as perhaps in most), rough customers could get ahead, despite illegal acts.

I’ve ordered books and articles from Interlibrary Loan, to continue my initial research about Major John Boone and his father-in-law Theophilus Patey. I want to get the facts straight.

Yet facts aren’t everything. Several recent posts on Twitter have questioned the power of facts (however reliable) to express the lived experience of our ancestors and families—their feelings, ideas, hopes, failures, family relationships, conflicts, dreams.

While I was discovering Major John Boone on the one hand, and on the other hand the surpassing beauty of Boone Hall Plantation, I was also reading (on the third hand, no doubt) “Soul Murder and Slavery: Toward a Fully Loaded Cost Accounting,” a 1995 essay by Nell Irvin Painter, which was given me by a friend.

Slave-dealing, religion, ambition, wealth, government, land, plantations, and families—all so important to Major John Boone—are the stuff of Painter’s essay. She asks penetrating questions about these elements of society.

Among Painter’s central points are these four:

Chattel slavery must include violence. “Societies whose economic basis rested on slave production were built on violence.” This violence, as physical beatings or sexual abuse, can inflict “soul murder” on its victims – a kind of degradation and depression and anger potentially fatal to self or others.

The violence of slavery can permeate an entire society, for blacks and whites, both within families and without. “The calculus of slavery configured society as a whole.” Slavery makes family life and social institutions less democratic and more tyrannical, for the slave masters as well.

In the Lowcountry South, the violence of slavery meshed with patriarchal attitudes in white society. At risk of abusive violence were black children, white children, black women, black men, and white women—everyone but the powerful white men themselves. Black children were beaten by their masters and their parents. Lawmakers and church leaders in the antebellum South routinely urged (white) female victims of wife abuse or incest to bear the abuse in a spirit of submission.

Today’s historians who want to understand slave society should let “the scales . . . fall from their eyes” in order to “look beneath the gorgeous surface that cultured slave owners presented to the world, and pursue the hidden truths of slavery, including soul murder and patriarchy.”

So I think of of Boone Hall and its gorgeous surface. I consider John Boone as plantation owner and ambitious slave trader. I ponder Soul Murder and Slavery. I see both beauty and terror here. I see the menace and lasting damage of a slave society, and I see the serene attraction of the monument that is Boone Hall Plantation.

Neither cancels out the other. Both are very real, and both are pinned to my spiritual bulletin board. Thorns and berries growing together, cultivated by the nature of human beings.

The Lowcountry Strawberry Festival will probably be on the schedule next year at Boone Hall Plantation.

Meanwhile, the familiar and painful echoes from slavery times are still heard in our national and private conversations.

Notes:

1. Schwab, William T. The Crofts of South Carolina. Mount Pleasant, SC: BookSurge Publishing, 2004. 19-20.

2. Baldwin, Agnes Leland. First Settlers of South Carolina: 1670-1700. Easly, South Carolina: Southern Historical Press, 1985. 30.

3. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boone_Hall. January 6, 2013.

4. Letters from the Clergy of the Anglican Church in South Carolina c. 1696-1775, ed. by George W. Williams. http://speccoll.cofc.edu/pdf/SPGSerie.... January 6, 2013.

January 1, 2013

Taming the Briar Patch

Here’s My Simple New Year’s Resolution: Focus.

This is a book blog for Into the Briar Patch: A Family Memoir. By focusing on my own Southern ancestors, the book explores some blockbuster questions. The purpose of this blog is to continue digging into these questions. Here are two of them:

What are the psychological origins of racism for whites in this country?

How can racism and the trauma of slavery be further healed, with compassion and respect for blacks and whites alike?

These two questions have an “action” component for me:

Last year, with research and great help from Twitter friends, I found several living Kirven (maternal-paternal) relatives who are biracial. Some of my (white) cousins and I are waiting for their further responses to my letters and phone inquiries. Would our biracial second cousins like to meet us? I hope so. But I’m not going to pester them or rush them.

This coming year, maybe I will find living Fraser (maternal-maternal) relatives who are biracial. If so, I’ll write more letters. I’ll hope again for a meeting.

Here are two more questions raised by Into the Briar Patch:

To what degree are people’s moral compasses shaped by historical contexts? Does everyone have a certain “core sense” of good and bad, or not?

Why do good people end up committing harmful acts, while still believing in the “goodness” or justifiability of these acts?

These two questions verge upon a classic problem, the origin of evil in human beings. At the end of Voltaire’s Candide, the bedraggled surviving characters lament to a wise philosopher: “But surely . . . there is a dreadful amount of evil in the world.” Why? They ask him. The philosopher tells them to shut up and slams the door in their faces.

Right. The best response is laughter. But the mystery of evil is still out there.

The briar patch of human nature has some mighty dark places. Yet we all start as babies, by our very nature good. Go figure.

Light and Shadow

These four questions make up focus of my blog, then. I’ll be attentive to healing action, the unexpected, humor, mystery, and the good/evil paradox of human nature. I’ll look for these themes as I keep searching for my living biracial second cousins, and as I contemplate the moral views expressed or acted-on by my Kirven and Fraser ancestors in the South.

So much to research and write about, I realize. I’ll be grateful if I can tame only my small section of the briar patch of human history.

We can pick only one berry at a time. And only when it ripens.

I’ll try to post weekly, whenever I come across a new living relative, an unexpected moral insight, a curious find, a mystery, or a story that brings a smile or a tear.

AND …

Happy New Year to my readers! I’m always glad to see your comments, thoughts, and questions!

December 13, 2012

Blog Caroling: “In the Bleak Midwinter,” with lyrics by Christina Rossetti

When I think of Christmas and winter, the first song I remember is “In the Bleak Midwinter,” with its haunting and persistent tune.

This carol is based on a poem written by a woman, the English poet Christina Rossetti, in the late 1800s. The composer is Gustav Holst. It became a Christmas carol in the early 1900s.

My husband and I first heard this carol when we joined the Westport Madrigal Singers in Connecticut, in the 1970s. We were impressed by its stark, simple, balanced kind of beauty.

Here is a version from youtube by the male trio “The Priests,” whose blended sound reminds me a little of our small singing group. It is less than four minutes, and you can follow the lyrics below:

In the bleak midwinter, frosty wind made moan,

Earth stood hard as iron, water like a stone;

Snow had fallen, snow on snow, snow on snow,

In the bleak midwinter, long ago.

Our God, heaven cannot hold Him, nor earth sustain;

Heaven and earth shall flee away when He comes to reign.

In the bleak midwinter a stable place sufficed

The Lord God Almighty, Jesus Christ.

Enough for Him, Whom cherubim, worship night and day,

Breastful of milk, and a mangerful of hay;

Enough for Him, Whom angels fall before,

The ox and ass and camel which adore.

Angels and archangels may have gathered there,

Cherubim and seraphim thronged the air;

But His mother only, in her maiden bliss,

Worshipped the beloved with a kiss.

What can I give Him, poor as I am?

If I were a shepherd, I would bring a lamb;

If I were a Wise Man, I would do my part;

Yet what I can I give Him: give my heart

December 7, 2012

Twelve Gifts of TIME, Please!

Just for fun, I’ll explain what I really want for the holidays, and as a matter of fact every day: TIME. Time to do genealogy and still have a life.

You, dear readers, are probably much better at getting your genealogy tasks done every day. I never finish my to-do lists. I dwell in an infinite sea of tasks, trying to stay afloat. No one else feels like that, right?

The best song I know about over-the-top gifts is The Twelve Days of Christmas, so I thought I’d start there. Except that I want all twelve gifts of Enough Time on the SAME day—the Perfect Genealogical Accomplishment Day.

And then I want that day to happen over and over, pretty please. Thank you, Santa.

So here goes my request for 12 gifts of Enough Time (in one repeated day), prompted by the “12 Days of Chrismas” carol:

“Twelve drummers drumming”:

Twelve cross-checked sources. Drumroll! These will add up eventually to the well-known Reasonably Exhaustive Search. Drumroll again!

“Eleven pipers piping”:

Eleven tweeters tweeting to me, and then I tweet back. We have extended meaningful conversations with links and pics and warm-hearted retweets.

“Ten lords a-leaping”:

Ten blogs a-posting, and leaping out to my reader’s eye. They each deserve a thoughtful comment. Well, I can do that now with my gift of Enough Time.

“Nine ladies dancing”:

Nine photo-scanning successes. Snap! That means each photo scanned with Flip-Pal, imported to laptop/iPad with caption and date, edited, sorted to folder. Boo-tee-ful.

“Eight maids a-milking”:

Milking is tough work. So here I need time for eight robust efforts to demolish a brick wall with newspapers, military records, library searches, tombstones, vital records through the mail, and what have you. Maybe the milk comes out, maybe it doesn’t.

“Seven swans a-swimming”:

Here I apply my caveat that I still want a life. So, seven units a-exercising. My current unit is 5 minutes—this means a half-hour walk. Won’t make me as slender as a swan, but will keep the blood running through my veins.

“Six geese a-laying”:

So many family letters a-laying around to be archived! For starters, to be put into acid-free folders and archive boxes. So, six letters. Or why not six whole packs of letters, since my gift will be Enough Time. Preserve those golden eggs for future generations!

“Five golden rings”:

Read five pages from my favorite classical genealogy text. Elizabeth Shown Mills, Val Greenwood, Marsha Rising . . . Hey, why not five chapters! I have Enough Time now.

“Four calling birds”:

Four new cousins calling. Surprise! Each one has a big new cache of well-documented family trees, wills, land deeds, and daily journals from the 1700s that are even now being mailed to me to be organized. Well, that’s all right, I have Enough Time now.

“Three French hens”:

Three contacts with genealogists, each contact as deliciously substantial as a French hen. I get to choose from webinars, conferences, podcasts, Blog Talk Radio….How lucky that I have Enough Time now so that I can do three in one day.

“Two turtle doves”:

Two techie updates. Sweet as turtle doves. I’m including only two, because I’m a bit slow reading those App instructions, even with my gift of Infinite Time. Yesterday, I downloaded some kind of photo app manual . . . 136 pages.

“And a partridge in a pear tree!”

Yes. One Fantastic Genealogical Find. I deserve it. We all deserve it.

Or. And? Writing One Informative and Loveable Blog.

Or maybe . . . Making a Mind-Blowing Supper. Use Instagram. Tweet it.

Now, I ask you. This isn’t much to want during one entire gi-normous day, is it? This is only what we all need. Fair is fair.

November 30, 2012

First Names of Slaves: Can You Locate Your Ancestors By Using My Ancestor’s Will?

African-Americans looking for enslaved ancestors often meet brick walls. There is no comprehensive index of African-American slave names—either their first names during enslavement or their first-and-last names when freedom finally came.

Some of the best clues to this information are in the documents of slaveholding families. An uncounted number of slaveholder wills do identify the first names of slaves who are being bequeathed as “property.” Because popular first names can pass down through a family, it becomes crucial to know the first names of one’s enslaved ancestors—in case they re-appear on the landmark 1870 census.

Slave ancestors may also have chosen to take the surname of their owner, or a variant of that surname, when they were freed. Having a plausible theory of both first name and surname of an enslaved ancestor can help bring about revelations from the 1870 or 1880 censuses.

In my opinion, there should be a complete database of slaveholder wills online, full of first names of slaves, and well indexed. Descendants of slaveholders could join to make this happen. It would be only fair.

Until that time, we soldier on individually.

Right now I can share 55 first names of slaves from the 1820 will of my 3 x great grandfather, John Baxter Fraser (1767-1820). I discovered his will last week.

Some background: John Baxter Fraser had a plantation in the Sumter District of South Carolina. He began working the fields in the 1790s, farming inferior land and living under frontier conditions, with 2 or 3 slaves. Through settlements of his white relatives’ estates, he owned 20 slaves by 1801. He lived in a 28 x 20 foot log house, and his slaves built log houses for their families. By 1820, his wife Mary and two children had died, but he had 9 remaining children, ages 11 to 30, to whom he bequeathed his farm supplies, his land, and his (by then) 55 slaves. In his will he kept together all of the slave families whom he owned.

Here are further ideas for anyone searching for enslaved Fraser ancestors. John Baxter Fraser also bequeathed his slaves’ “future increase” (children) to his own children, and instructed them to bequeath these slave families and their “increase” to their own children—or if they had none, to their surviving white siblings.

Therefore, until the end of the Civil War, the families of these 55 enslaved people would probably have lived with some white family surnamed Fraser (Frasier, Frazier, Frazer) either in the Sumter District of South Carolina, or wherever that family moved. Here I give the BD dates of each of the 9 Fraser children, and the probable married names of the Fraser daughters, to aid genealogical searches. I also include possible places to which each Fraser sibling may have relocated. (These relocation suggestions are from those infamously unverified public family trees, but surely every hint is welcome in a caring search.)

As it happens, one of John Baxter Fraser’s sons is my 2 x great grandfather, Ladson Lawrence Fraser (1804-1889):

Ladson Lawrence Fraser (1804-1889). Photo owned by author.

He and his wife Hannah Boone owned a Boone-Fraser plantation, Booneland:

Booneland. Photo owned by the author.

First Names of Slaves in the 1820 will of John Baxter Fraser, as willed to his children:

To Samuel Fraser (1790-1843): Ben, Diana her child Xury and her future increase, and the negro girl Delia my negro slaves Toney & Affy Samuel may have been buried at Pawleys Island, Georgetown, South Carolina.

To Mary Fraser (1792 – ): Cyrus, Milly and her children to wit Amoutta, Satira, and July and my waiting Boy Primus, Lucy and her two children Labinia and Abeline Mary may have been married to Sinclaire Deschamps.

To William Hickman Fraser (1793-1864): Caesar & his wife Dorcas, George, Liddy and her two children Lembrick and Dorcas William may have died in Darlington, South Carolina.

To Jane Baxter Fraser (1794-1840): George & his wife Brunette, Lucy & her two children To wit Peggy & Nelson, and my negro girl Charlotte Jane may have married Thomas Boone in 1827.

To John Glasgow Fraser (1796-1860): Tome and his wife Dince & her child Heriott

To Thomas Fraser (1798-1863): Judith, Frank, Prince, Silla & her two children. Viz. Sylva and Abigail Thomas may have moved to Alachua, Florida, and had many children.

To Robert Fraser (1800-1886): old Ben, old Suckey his wife, Tyler, Nero, Dandy, Maria and her child Argen Robert may have moved to Bishopville, South Carolina.

To Ladson Lawrence Fraser (1804-89): Dick, & his wife Kate, Nanny & her three children vix. Heram, Rufus, and Susanna Ladson stayed in Sumter District, South Carolina.

To Elias Lynch Fraser (1809-51): Anthony, Ambrose, Marianne, Daphan young Suckey, and Sophronia Elias may have moved to Lancaster, South Carolina, and had a number of children by his first and second wives.

Given the terrible reality that people were enslaved and then bequeathed as property, I hope this information can help some African-Americans trace their ancestors and learn more about their families.

Sources: The full source for John Baxter Fraser’s history is Cotton Culture on the South Carolina Frontier: Journal of John Baxter Fraser 1804-1807, edited by John Hebron Moore and Margaret DesChamps Moore. This book holds some more information about the 55 enslaved people and their lives with John Baxter Fraser. It is available from the South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

The entire 1820 will of John Baxter Fraser can be found here.

*** Footnote relating to my last blog: I’ve received a brief, tentative response from my letter. My relative is considering what to do and talking the matter over with her aunt. She says she’ll let me know. I am waiting hopefully.

November 13, 2012

Of Bait and Cousins

Bait. The word can have a sinister overtone. John Donne’s poem “The Bait” warns of lures and traps—seduction.

Of course, when genealogists put out “cousin bait” on blogs and message boards, their intentions are totally benign. They’re extending handfuls of information, to promote new family connections and friendships. The term “cousin bait” becomes a good-hearted joke: absolutely no harm is meant.

I’m composing a new letter today, to introduce myself to a living biracial relative, Z, whom I found behind my brick wall (previous posts). As I write, the term “cousin bait” pops into my head, bringing questions that are no joke. Will my relative read my letter with suspicion? Will she wonder whether it’s safe to answer me? Or whether my invitation to meet and talk is some kind of trap, with strings attached? Why should she trust a letter that appears in her South Carolina mailbox from some strange white woman who lives “up North”?

As I mull over her possible responses, I review the letter to A that I wrote a month ago. He, A, was the first biracial relative whom I found, and I wondered how to approach him.

At that time, I listened to Bernice Bennett’s radio show with Sharon Morgan and Thomas DeWolf, co-authors of Gather at the Table: The Healing Journey of a Daughter of Slavery and a Son of the Slave Trade. I typed in my question. Sharon advised me to be straightforward, without speeches or information overload. Like this: “Through research I’ve found we might be related. I’d really appreciate being able to talk with you.”

So this is the letter to A that I wrote last month:

Dear A,

My name is Mariann Regan, and I live in Connecticut. I am a retired teacher, white, and xx years old.

My mother’s maiden name is B. Her ancestors were from C.

Through research, I have recently discovered that you and I may be relatives. I found your address on www.peoplesmart.com.

I would really appreciate being able to talk with you by telephone, if that is all right with you. I would like to ask you the names of your grandparents and great-grandparents, on the B side. If my guess is correct, we may discover how we are related.

I would welcome an email, letter, or telephone call from you at any time. My phone number is xxx.

Good wishes and good health to you,

Mariann

Today this straightforward letter sounds to me rather abrupt. In fact, A did not answer the letter. Perhaps at 85 years old, he was too tired or ill to take on a new project. Still, maybe I can write an improved letter for Z.

Recently I read a blog post by Terri O’Connell @Tracingmyfamily, subtitled “Cold Calls or Snail Mail?” She explained that her letters to prospective relatives have genealogical information, a family tree, and a self-addressed stamped envelope. That sounded good to me.

So here is the letter I’m sending to Z tomorrow:

Dear Z,

It may seem to you that I am a stranger, but my recent research shows that you are likely to be kin to me and to my family in South Carolina.

I believe our families have been related since 1855. In those long-ago days, families may not always have been informed that they were related. Times are now changing. Prejudices of all kinds are starting to heal. More information has come to light.

I’ve found information that you may be the daughter of Y, who is the son of X, who is the son of W (born 1855), who is the son of V and U.

I am the daughter of T, who is the daughter of S, who is the son of V and R.

In other words: Your great-great grandfather V is the same person, I believe, as my great-grandfather. You and I would be second cousins once removed.

I’m xx years old and a retired English teacher, in Connecticut since 1964. I’ve recently studied family history and re-connected with my South Carolina family.

Several of our family would like to contact you and your family, while at the same time respecting your privacy. We would really appreciate being able to talk with you. We believe it can be a good thing for families who have been separated by the historical injustices of the past to get together and talk, if that is their choice today.

I would greatly welcome a letter, phone call, or email from you. I’ve enclosed a self-addressed and stamped envelope. My home phone is xx, and my cell phone is xxx. Email: yy or yyy.

With all sincere good wishes,

Mariann Regan

In this version I’m trying to be more easygoing and friendly, without using any startling words like “slavery.” Perhaps bait and outreach do overlap? I wonder what words are adequate to suggest welcoming with open arms.

This relative may know of others, also with connections to our family, who live in the same area. I hope so. This country is full of unacknowledged biracial cousins who to this day are strangers. Changing that situation would be a step forward.