S.B. Stewart-Laing's Blog, page 6

May 7, 2014

Performing Acceptable Breaks From Reality, Part II

'Of course, it depends how realistic you're actually trying to be.'

--Stu

Fiction, by its nature, does its job by stepping away from reality as we know it. Sometimes, it simply presents a more distilled version of life as we know it, with the key conflicts and meaningful moments of a fictional life plucked out and highlighted for the reader. Other genres go radically further, and imagine worlds where time and space play differently, where magic is mundane, or where humans have never existed.

No matter how fantastic or how ordinary the setting, however, it needs to maintain a level of internal consistency to be real to the reader. Once we've established the rules of the world, they must be adhered to throughout the narrative, or we'll lose the illusion. Of course, this typically means we'll happily accept fictional events that defy the known laws of physics if we know it's normal for that world.

To actually pull this off, we need to be fully aware of the rules of the game in our created setting. Realise that these will constrain your characters at some point-- if a fall from a helicopter into the ocean pulverises the bad guy's internal organs, there had better be a solid explanation why the hero doesn't meet the same fate. (Ideally, the groundwork for any such lucky escapes will be laid in advance; alternately, consider the possibility of your hero being wrong, getting seriously injured, or even dying in the course of the narrative).

The key is to use the genre-acceptable break from reality consciously, rather than slapping it in because everybody else is doing it. Also, working in a fantastic or exaggeration-filled genre doesn't require you to use all over-the-top tropes all the time. A little realism can be refreshing or add some extra tension to the storyline.

--Stu

Fiction, by its nature, does its job by stepping away from reality as we know it. Sometimes, it simply presents a more distilled version of life as we know it, with the key conflicts and meaningful moments of a fictional life plucked out and highlighted for the reader. Other genres go radically further, and imagine worlds where time and space play differently, where magic is mundane, or where humans have never existed.

No matter how fantastic or how ordinary the setting, however, it needs to maintain a level of internal consistency to be real to the reader. Once we've established the rules of the world, they must be adhered to throughout the narrative, or we'll lose the illusion. Of course, this typically means we'll happily accept fictional events that defy the known laws of physics if we know it's normal for that world.

To actually pull this off, we need to be fully aware of the rules of the game in our created setting. Realise that these will constrain your characters at some point-- if a fall from a helicopter into the ocean pulverises the bad guy's internal organs, there had better be a solid explanation why the hero doesn't meet the same fate. (Ideally, the groundwork for any such lucky escapes will be laid in advance; alternately, consider the possibility of your hero being wrong, getting seriously injured, or even dying in the course of the narrative).

The key is to use the genre-acceptable break from reality consciously, rather than slapping it in because everybody else is doing it. Also, working in a fantastic or exaggeration-filled genre doesn't require you to use all over-the-top tropes all the time. A little realism can be refreshing or add some extra tension to the storyline.

Published on May 07, 2014 02:24

May 5, 2014

Performing Acceptable Breaks From Reality, Part I

In response to my post on the difference between fictional glass (easily broken by the hero jumping from a window) and real glass (hard and sharp), I received the following comment:

There's a lot to be said for good escapist entertainment. Stories may be the way we as a species reinforce our social norms and defining narratives, but they're also a way for us to escape to a landscape that is more thrilling, more emotionally intense, and most importantly, less messy and painful and complicated than our everyday existence (when fiction is messy and emotionally grueling, we can shut off the movie or close the book).We gain satisfaction from seeing Bond bring down the bad guys, and we feel that satisfaction on a visceral, biological level.

So why do we see heroism as entwined with over-the-top action? I think this stems from the place of the 'Hero' in our storytelling culture. Joseph Campbell highlighted the fact that all cultures share a Hero's Journey arc in their mythology; the Hero stands for all of us, and is a vessel for our values and aspirations. We need this character to accomplish larger-than-life feats because that is their job-- to show us how to overcome the seemingly impossible.

At the same time, we don't necessarily need action to make our hero extraordinary. They can be extraordinary smart, or brave, or empathetic, or talented in their particular area. Decorating their journey with enjoyably over-the-top action tropes doesn't make them a hero in and of itself. It's their resourcefulness and resilience in pursuit of a worthy goal.

'Heroism demands such scenes and I think they are acceptable by the audience and readers also.'

--Cifar Shayar

There's a lot to be said for good escapist entertainment. Stories may be the way we as a species reinforce our social norms and defining narratives, but they're also a way for us to escape to a landscape that is more thrilling, more emotionally intense, and most importantly, less messy and painful and complicated than our everyday existence (when fiction is messy and emotionally grueling, we can shut off the movie or close the book).We gain satisfaction from seeing Bond bring down the bad guys, and we feel that satisfaction on a visceral, biological level.

So why do we see heroism as entwined with over-the-top action? I think this stems from the place of the 'Hero' in our storytelling culture. Joseph Campbell highlighted the fact that all cultures share a Hero's Journey arc in their mythology; the Hero stands for all of us, and is a vessel for our values and aspirations. We need this character to accomplish larger-than-life feats because that is their job-- to show us how to overcome the seemingly impossible.

At the same time, we don't necessarily need action to make our hero extraordinary. They can be extraordinary smart, or brave, or empathetic, or talented in their particular area. Decorating their journey with enjoyably over-the-top action tropes doesn't make them a hero in and of itself. It's their resourcefulness and resilience in pursuit of a worthy goal.

Published on May 05, 2014 02:16

May 2, 2014

End of A to Z Challenge

Thank you to all you lovely readers who stopped by during the A to Z challenge! You made the month fun and thought-provoking. The comments you left showed that you all have creative, inquiring minds, and hopefully we've started some fruitful discussions. I know a lot of the comments got me thinking.

In fact, over the next few weeks, I'll be writing posts inspired by comments left during A to Z challenge. Stay tuned to see if yours is one of them. In the meantime, enjoy this video of a mouse-deer:

In fact, over the next few weeks, I'll be writing posts inspired by comments left during A to Z challenge. Stay tuned to see if yours is one of them. In the meantime, enjoy this video of a mouse-deer:

Published on May 02, 2014 01:35

April 30, 2014

Z is for Zero Gravity, Zero Problems

In most space-faring sci-fi, we accept a number of high-tech innovations must exist in-universe to make the story possible. Faster-than-light travel is a must if your characters are going to check out other planets. So is artificial gravity.

In spite of the perception that zero gravity means cool floating objects and not much else, there are actually a number of major problems facing humans in space. The human body is adapted to Earth's gravity, and sustained weightlessness causes all kinds of physiological problems, from osteoporosis to anemia. We have not currently figured out how to create an artificial gravity field, but when we do, it will surely be technologically complex and energetically expensive to run.

There are all kinds of cool plot possibilities here, whether you place your characters in a contemporary space environment (like Gravity ) or whether you have futuristic characters grappling with zero-gravity issues during their travels across the galaxy. If you want ideas, check out the Video From Space YouTube channel, and enjoy some very cool videos (like the one below) of the trivial tasks of everyday life made challenging by the lack of gravity.

In spite of the perception that zero gravity means cool floating objects and not much else, there are actually a number of major problems facing humans in space. The human body is adapted to Earth's gravity, and sustained weightlessness causes all kinds of physiological problems, from osteoporosis to anemia. We have not currently figured out how to create an artificial gravity field, but when we do, it will surely be technologically complex and energetically expensive to run.

There are all kinds of cool plot possibilities here, whether you place your characters in a contemporary space environment (like Gravity ) or whether you have futuristic characters grappling with zero-gravity issues during their travels across the galaxy. If you want ideas, check out the Video From Space YouTube channel, and enjoy some very cool videos (like the one below) of the trivial tasks of everyday life made challenging by the lack of gravity.

Published on April 30, 2014 02:28

April 29, 2014

Y is for Young Adult Attitude

The human brain is an astonishingly complicated organ. While most of our body is complete by the time we're in our late teens, the brain isn't finished developing until we're 25. Because of this, adolescence isn't just about social norms, but a phase of neurological development. Teenagers everywhere have always been more emotional and more impulsive than adults because of human biology, so the idea that in the distant past youngsters were collectively devoid of typical 'teen' impulses is nonsense.

However, a lot of stories-- particularly in the fantasy genre-- seem to make the opposite assumption: that teenagers act like spoiled, ignorant brats*, regardless of their environment. This is an assumption that carries over into general attitudes towards teenagers, no matter what the relevant circumstances.

Setting aside variations in personality and developmental speed, environment (physical, socioeconomic, cultural) plays a big role in shaping how a young adult responds to the world. Sure, they may have more dramatic emotional reactions, but what they do with those reactions is very much a product of the opportunities around them. Someone whose day is regimented by intensive schooling and cultural expectations of intense study, or by dawn-to-dusk labour on a farm or in a factory, won't have the time or energy to 'act out';someone with a lot of free time and access to supplies might create art; someone with few resources but frustration might eschew angsty poetry for picking fights and breaking windows. And although the teenage brain is programmed to some degree to see its owner as the centre of the universe, someone raised in a collectivist culture, or in deprivation, may be less inclined to develop this into a full-blown entitlement attitude.

Besides being aware of the individual personality of the teenager you're writing, it's worth thinking about their culture and how that will interplay with their adolescent brain.

*I count characters who behave this way and are not called out by the narrative in my sample.

However, a lot of stories-- particularly in the fantasy genre-- seem to make the opposite assumption: that teenagers act like spoiled, ignorant brats*, regardless of their environment. This is an assumption that carries over into general attitudes towards teenagers, no matter what the relevant circumstances.

Setting aside variations in personality and developmental speed, environment (physical, socioeconomic, cultural) plays a big role in shaping how a young adult responds to the world. Sure, they may have more dramatic emotional reactions, but what they do with those reactions is very much a product of the opportunities around them. Someone whose day is regimented by intensive schooling and cultural expectations of intense study, or by dawn-to-dusk labour on a farm or in a factory, won't have the time or energy to 'act out';someone with a lot of free time and access to supplies might create art; someone with few resources but frustration might eschew angsty poetry for picking fights and breaking windows. And although the teenage brain is programmed to some degree to see its owner as the centre of the universe, someone raised in a collectivist culture, or in deprivation, may be less inclined to develop this into a full-blown entitlement attitude.

Besides being aware of the individual personality of the teenager you're writing, it's worth thinking about their culture and how that will interplay with their adolescent brain.

*I count characters who behave this way and are not called out by the narrative in my sample.

Published on April 29, 2014 02:18

April 28, 2014

X is for X Marks the Spot

It's one of those iconic images of a pirate stories: the map with a big X marking the buried treasure. And after almost a full month of bursting bubbles and naysaying everyone's favourite action-adventure tropes, I'm here to tell you that there's real pirate treasure out there for the finding.

It's one of those iconic images of a pirate stories: the map with a big X marking the buried treasure. And after almost a full month of bursting bubbles and naysaying everyone's favourite action-adventure tropes, I'm here to tell you that there's real pirate treasure out there for the finding.Piracy has been around since the first traders took to the ocean, but the hayday of high-seas bucaneering was between [years]. As sailing ships carried good across the Atlantic and Pacific by the thousands, the opportunities to make a quick fortune as a pirate or privateer (a pirate operating under the auspices of a sponsor government) became an increasing temptation. The life of a 17th century pirate was high-risk, which meant that quite a bit of hidden treasure never got retrieved, was washed overboard in storms, or sank with a ship. Add to that the high number of legitimate merchants whose vessels went down, and you have a significant amount of buried or sunken treasure waiting to be discovered.

Worried that the long-sunk booty actually belongs to someone else? As it turns out, international maritime salvage laws are on your side (what good is a Maritime Law class if you can't use your newfound knowledge to go treasure-hunting?), providing you have the time, money, and energy to go looking. For the rest of us, Treasure Island is available as a free ebook from Project Gutenberg, so you can do your treasure-hunting vicariously.

Published on April 28, 2014 01:18

April 26, 2014

W is for 'We Have to Get the Bullet Out!'

'The doctors killed [President] Garfield, I just shot him.'

'The doctors killed [President] Garfield, I just shot him.'--Charles Guiteau

Once a character gets shot in Fictionland-- usually with a bullet, but sometimes with an arrow or other weapon-- it's a mad scramble by the team medic to get the offending object out of the wound. I've already covered how TV first aid has an unfortunate tendency to become an instruction manual for the clueless and well-intentioned during an emergency, so before we analyse further:

If someone has been shot, stabbed, or otherwise punctured, DO NOT attempt to extract the object.

The gunshot version of this trope actually has a reasonable origin. Before the invention of bullets, getting shot meant being punctured by a relatively large and slow-moving ball, which often tracked clothing or other debris into the wound. Getting the debris out reduced the chance of infection, and so was worth the other risks.

In modern times, however, the only circumstance in which one would want to remove an object from a wound is if the object itself is acutely toxic. Searching for an embedded bullet may cause more injuries than the original gunshot, and can also introduce bacteria or other foreign objects into the victim's insides. Similarly, removing something like an arrow or stick can cause additional damage on the way out. Plus the object in the wound is very likely acting as a cork, compressing tissues and blood vessels so that blood loss is minimised. With this plug removed, the victim will probably experience additional blood loss.

If your characters must go pulling objects out of wounds-- they're doctors, they don't know any better, they're Kryptonite bullets, or they live in the 15th century and have no 'option B'-- that's fine. I'd suggest realistic medical complications where genre-appropriate, but go to it.

However, I would once again seriously recommend first aid classes to anyone who can find the time. They are often free, held at convenient hours, and provide critical knowledge, even if you hope you never have to use it outside of writing your novel.

Published on April 26, 2014 01:57

April 25, 2014

V is for Virginity Confirmation

In a world filled with gendered double standards, one that is represented across many cultures is a fixation on female virginity. Fiction certainly showcases a wide variety of tropes on the subject, one in particular causes real-life problems for women worldwide. Namely, the assumption that virginity is synonymous with an intact hymen, and that a true virgin will always bleed the first time she has (heterosexual) intercourse.

[Note: Mildly NSFW due to reproductive biology and sex discussion. Click through for full post]A number of countries and cultures still use 'virginity tests' to determine if a woman is fit for marriage. If her hymen is not intact, she is considered soiled, which can have major social consequences. So high are the stakes that women often seek surgery (illegal in some countries, but performed anyway) to 'reconstruct' their hymens so that their lady parts will meet expectations, including inserting a packet of fake blood.

Setting aside the ethics of demanding that a woman remain a virgin until marriage, the obsession with the hymen and bleeding is absurd. Depending on the person, the hymen may be nearly absent, already broken from athletic activities, or simply supple enough to stretch instead of tearing the first time around.

This isn't so much aimed at contemporary writers as an illustration of how deeply a storytelling prop can become ingrained in social expectations.

[Note: Mildly NSFW due to reproductive biology and sex discussion. Click through for full post]A number of countries and cultures still use 'virginity tests' to determine if a woman is fit for marriage. If her hymen is not intact, she is considered soiled, which can have major social consequences. So high are the stakes that women often seek surgery (illegal in some countries, but performed anyway) to 'reconstruct' their hymens so that their lady parts will meet expectations, including inserting a packet of fake blood.

Setting aside the ethics of demanding that a woman remain a virgin until marriage, the obsession with the hymen and bleeding is absurd. Depending on the person, the hymen may be nearly absent, already broken from athletic activities, or simply supple enough to stretch instead of tearing the first time around.

This isn't so much aimed at contemporary writers as an illustration of how deeply a storytelling prop can become ingrained in social expectations.

Published on April 25, 2014 01:04

April 24, 2014

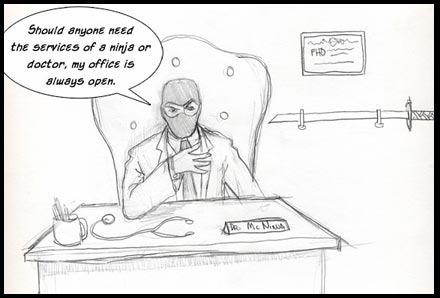

U is for Universal Scientists

Back when I was applying to my postgrad, my biggest academic anxiety was my lackluster grades in intermediate chemistry and physics. When I voiced my concerns to my prospective postgrad advisor, he was entirely unconcerned.

Back when I was applying to my postgrad, my biggest academic anxiety was my lackluster grades in intermediate chemistry and physics. When I voiced my concerns to my prospective postgrad advisor, he was entirely unconcerned.'Don't worry,' he said. 'It's not like you're going to need it again.'

Even as someone doing an interdisciplinary thesis, it turned out, I had already specialised my way out of any number of fields.

You wouldn't guess that, though, by looking at fictional scientists. Anyone behind a fictional lab coat can suture an artery, whip up a vaccine, split an atom, identify a rare species of rainforest bat, build a battery, calculate a Bayesian probability model to predict the age of the villain, and then take said villain down with a contraption made of rubber bands, frozen fish, and an antique lightbulb.

Back in the 16th and 17th centuries, it was much more feasible for a single person to know all there was to know about 'natural philosophy', since the sum total of human scientific knowledge was pretty limited. Once the rate of scientific discoveries really began to pick up, however, there was simply too much knowledge for one human to know it all. Now, when the rate of new discoveries in some fields-- particularly genetics and cellular biology-- necessitates new textbooks being printed annually, it's hard enough to keep up with the cutting edge of one field, let alone many. So while your fictional modern scientist may have a solid comprehension of fields outside their specialty, they will have tip-top skills only in their area of expertise.

Published on April 24, 2014 01:20

April 23, 2014

T is for Televisually Transmitted Disease

Foreman: First year of medical school - if you hear hoofbeats you think horses, not zebras. House: Are you in first year of medical school? No. First of all, there's nothing on the CAT scan. Second of all, if this is a horse then the kindly family doctor in Trenton makes the obvious diagnosis and it never gets near this office. --House

PSA: Since we're talking about rare diseases today, it's worth pointing out that it's Porphyria Awareness Week!

If a story is set in a hospital, a good portion of the drama comes from the patients. And the audience can bet that this won't be a parade of flu and broken bones and heart disease. In fact, the rarer a malady, the more it seem to make appearances in fictional doctors' offices. Popular choices are Congenital Insensitivity to Pain (incidence 1 in 25,000 people), various types of porphyria (incidence 1 in 40,000 people), conjoined twins (about 1 out of 100,000 live births), and intersex patients (1 in 50,000 people).

In spite of complaints that portraying rare ailments in the media prompts perfectly healthy people to panic-search symptoms on WebMD, I'd argue that showing rare diseases in the media is a positive thing. Because of the rarity of many of the conditions that get play on medical shows, patients with these diseases are often misdiagnosed or ignored unless the patient or doctor happens to recognize the symptoms for what they are. And yes, there is at least one documented case of someone seeing their symptoms on TV and rushing to the doctor just in time. If the rare illnesses are portrayed in realistic detail, these fictional presentations have the potential to raise awareness and potentially guide people to the specialist medical care they need.

PSA: Since we're talking about rare diseases today, it's worth pointing out that it's Porphyria Awareness Week!

If a story is set in a hospital, a good portion of the drama comes from the patients. And the audience can bet that this won't be a parade of flu and broken bones and heart disease. In fact, the rarer a malady, the more it seem to make appearances in fictional doctors' offices. Popular choices are Congenital Insensitivity to Pain (incidence 1 in 25,000 people), various types of porphyria (incidence 1 in 40,000 people), conjoined twins (about 1 out of 100,000 live births), and intersex patients (1 in 50,000 people).

In spite of complaints that portraying rare ailments in the media prompts perfectly healthy people to panic-search symptoms on WebMD, I'd argue that showing rare diseases in the media is a positive thing. Because of the rarity of many of the conditions that get play on medical shows, patients with these diseases are often misdiagnosed or ignored unless the patient or doctor happens to recognize the symptoms for what they are. And yes, there is at least one documented case of someone seeing their symptoms on TV and rushing to the doctor just in time. If the rare illnesses are portrayed in realistic detail, these fictional presentations have the potential to raise awareness and potentially guide people to the specialist medical care they need.

Published on April 23, 2014 01:39