Charles Martin's Blog, page 22

February 2, 2015

This is not an article about American Sniper

I haven’t seen America’s latest patriotic Rorschach test. However, its success has helped bring attention to a Hollywood organization comprised of veterans and industry insiders called Got Your 6. Got Your 6’s aim is to certify (a nebulous, Orwellian term if my cynical eyes ever saw one) films about veterans as authentic. They want to discourage stereotypes—especially that of the broken, embittered, trauma-ridden veteran—and encourage more positive, “realistic” portrayals of our warriors.

Even the First Lady put her support behind the organization—a move that is sure to be less controversial than, say, encouraging children to eat more vegetables. At a recent press conference, she expressed her hope that programs like Got Your 6’s will help integrate veterans back into civilian communities by changing public perceptions about them. Got Your 6’s website states that the organization hopes “to normalize depictions of veterans on film and television to dispel common myths about the veteran population.”

When I came home from war, I wasn’t violent—but I was kind of a piece of shit. I treated people poorly, isolated myself, and drank too much. My first nine months or so back did not consist of the sterling veteran example that Got Your 6 may want to encourage. Certainly, my time since then—continuing my education, furthering my writing career, getting married, starting a small business—is more inspirational and positive than staying up late taking amphetamines, pounding cheap beer, and playing videogames every weeknight. But the successes in my life—and the turnarounds—are made all the more profound by the struggles that I experienced, and, in some cases, put myself through. Would my story, especially its darker parts, get the seal of approval from Got Your 6 if I didn’t tack on the positive stuff?

By what metrics will Got Your 6 certify a work as accurate or appropriate? When does a lingering problem in the veteran community, like alcoholism, depression, or suicide become a “myth”? I tried to watch the Operation Got Your 6 video to find out how they would be evaluating films and shows—but the condescending Madagascar Penguins sketch brought up too many bad memories of childish AFN commercials encouraging me to wear my reflective belt while doing morning PT. (For extra irony, picture watching these commercials the morning after a mortar attack.)

While I’m happy to see that there’s a push against stereotyping veterans—Got Your 6 probably wouldn’t give its stamp of approval to movies like Harsh Times or Brothers—would it approve more nuanced (and sometimes negative) but realistic films or shows? I have no doubt Band of Brothers would get a thumbs up—but would The Pacific or Generation Kill earn that certification, considering both were criticized for depicting American war crimes and for questioning how much good those marines were actually doing? What about Platoon, a film that many soldiers love despite its worst-case-scenario depiction of the Vietnam War? I assume The Hurt Locker, the feel-good comedy of 2008 would get the seal of approval because of its critical and commercial success, despite the fact that it’s essentially a Hollywood producer’s secondhand notion about what the Iraq War was like.

Conversely, what are the consequences for getting this group’s thumbs down? What if a film, show—or maybe a book—by a veteran gets panned by this organization? Does that mean it’s less true or authentic? What are the consequences of such a rejection? Will Got Your 6 take to social media to encourage people not to see it? In my experience, the “real” war was always the one you were fighting—guys in other fire teams, squads, platoons, companies, battalions—they didn’t get it. Now Hollywood producers and a handful of vets I’ve never met get to say whether someone else’s story is the real deal?

My fear is that, while well-intentioned, Got Your 6 will simply be a pressure group demanding that all veteran stories have a happy ending, or that the positive depictions outweigh the negative in a given work. That’s not a good way to evaluate art. That’s not a good way to tell the truth, either.

War’s impact goes well beyond the battlefield. It ruins nations, and it ruins people. It can also make those who went through it stronger—but to pretend that every story has a happy ending, or that everyone who comes out of war is better for the experience—is authoritarian myth-making.

It’s propaganda, especially in light of recent scandals at the VA, wherein government bureaucrats are directly responsible for the death of many veterans. I’m more bothered by that more than what some stupid movie says. But not a lot of my fellow Americans seem to care about secret death panels. Remember how we all laughed at Sarah Palin for using that phrase?

Turns out the joke’s on us. Or rather, it’s on the old guys who went off and did our dirty work in some Hell-on-earth half a world away. But, to quote World War II veteran Kurt Vonnegut—so it goes.

Could our society benefit from more positive portrayals of veterans in TV and film? Absolutely. And I’ll support the artists trying to make that happen—as long as they don’t lose sight of the nuance and hard truths of our stories. Not everyone’s war is over when the credits roll and the somber-but-hopeful music plays as you file out of the theater.

To think otherwise does a true disservice to our veterans.

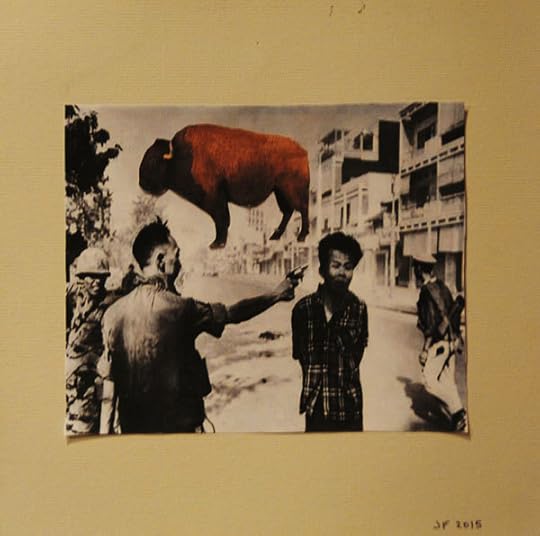

Nguyen Ngoc Loan w/ Bison

January 30, 2015

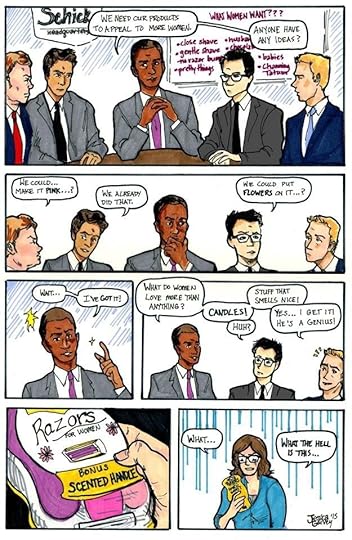

For Women

January 22, 2015

Women Knights

January 21, 2015

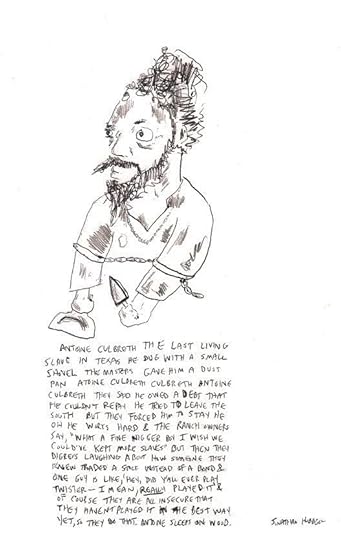

Antoine Culbreath

January 20, 2015

Jesus the Executioner, or How to Create a Home for Your Own Personal Jesus

The world is composed of words, and the words possess a multiplicity of meanings, leading to a multiplicity of worlds. Living in Oklahoma is its own special reward and punishment, and the week that just passed offered much of what it means to live in a different world than your neighbor. The execution of a child murderer in the state this week gave Oklahomans an opportunity to choose which world they inhabited, and many sided against their own god. But first, the opening statement deserves some parsing.

My experience of the world is shaped by the words offered me as I grow up in whatever corner of the world is my home.[1]This is not as axiomatic as you would think. People honestly believe they are growing up in a world that is shaped by an objective understanding of truth, largely because their parents, the first humans to offer them vocabulary, believe the same thing. One example should suffice.

If I grew up in Augusta, Ga., and my parents sent me off to church camp as a child or teen, the preparation for the event would already have occurred at the level of language. Likely I would have been raised in church, but even if I hadn’t, the preparation would have taken place. Religious experience for a young, white, middle class kid in the South would involve words like Jesus, church, sin, salvation, heaven, and hell. (I realize the world is changing, but the way we explain experience via words is lagging behind our experience of the world.)

One night, in the middle of an altar call at this youth camp, I might respond to the throbbing guilt the speaker has created in my conscience. I move to the front where a “counselor” or volunteer is waiting for me. After a brief chat, I say the words I have been instructed to say: “Dear Jesus, I’m a sinner. Please forgive me of my sins. I want you to come live in my heart and be my Lord and Savior. Amen.” Some variation of that, which evangelicals and fundamentalists call the Sinner’s Prayer, would be the recommended response to the existential angst I am feeling. I would be declared “saved” at that moment, and if the counselor is conscientious, I’ll be told what to expect in the coming weeks.

Imagine that scenario playing out in India or Saudi Arabia or Tel Aviv or Bangkok. The words, the gods, the experience, the expectations—all would be different. My experience of the world would be shaped, not by a literal Jesus showing up to forgive my sins, but by an interpretation of what I’m feeling offered by people who believe they understand the world, both at the level of language and at the level of objective reality. This is, of course, a fiction; it’s merely a construct based on a preference or a tradition to which the participants subscribe.

Place those understandings and lexicons side by side, and we arrive at the current state of our world: a multiplicity of worlds existing contiguously. Is there a “real” world that we are attempting to understand and that we can possibly come to experience? Science offers us some insight into that “real” world, but science, as poet Stephen Dunn reminds us, makes for a poor story at times: “You can’t say, ‘Evolution loves you,’ to your child.”[2] This is not to deny that science can be a remarkable story, but myth shapes us far more than science. Make of that whatever you wish: praise or lament.

So we arrive at the week past in Oklahoma. For the first time since the state botched an execution badly, an execution was scheduled. A very divided Supreme Court refused to halt the execution, and so it went forward. The Associated Press reported that Charles Warner said, “My body is on fire,” after the first of three drugs was administered. We should be clear. Warner raped and murdered an 11-month old child. An act that heinous defies our ability to imagine much worse, unless the crime was multiplied to include other children. By any standard of human behavior, Warner failed to even measure up to a minimal definition of human. I’ll side with Pico della Mirandola here, and say that our behavior has the potential to make us less than human. His frame of reference was the Great Chain of Being—an absurd idea—but his conclusion is solid. Warner was a beast in that choice, or worse than a beast, in fact. His actions are indefensible, and it is difficult to feel pity for him, even if his body did feel like it was on fire.

Still, the responses have been illustrative of the multiple worlds we inhabit. I watched with fascination as a friend attempted to be reasonable on Facebook as he called on the officials in our state to give up capital punishment. He referred to the circumstances surrounding the execution as shameful. No one, after all, should have to die in torment. One lovely woman offered that it would be a shame not to execute such a person, and, she continued, she hoped he was raped while in prison. This is such a common refrain in ethics class, I brace myself each semester for it. Good Christian students advocating proxy rape.

How does the crucified savior worshiped by Christians lead to Christians advocating execution and proxy rape? What world do they inhabit? Surely it isn’t the same as Jesus. He offered salvation to all, if the story is to be believed, so what causes people who allegedly believe the story to abandon hope for redemption and demand execution? If their understanding of the world is shaped by words like forgiveness, restoration, and redemption, how do they become cheerleaders for a system of execution? Should they not lobby for life in prison, hoping and praying that the offender comes to receive grace?

It seems their world has been compartmentalized into areas of salvation and politics. The former is guaranteed them by virtue of their confession of being a sinner via the Sinner’s Prayer, but it is clearly not available to all, at least not pragmatically speaking. While heaven is open to all, according to the mythology, there seems to be a grammar of preference into who actually makes the cut. Salvation, it seems, is not free to all who ask. The political narrative is constructed to order their world according to their preference. Of course Jesus hates baby killers. He didn’t die for everyone, only the ones who sin within a comfortable set of parameters. The great irony is that they view outsiders as an enemy of the truth, but it is they who have reduced their Lord to one who can only save the practitioners of pedestrian sins.

1 This is an idea that I’m pretty sure I got from reading Ludwig Wittgenstein, one of my philosophy heroes, but it’s possible I only inferred it from conversations in classes about Wittgenstein in grad school. Whatever the case, I’m convinced it describes our experience accurately.

2 At the Smithville Methodist Church, Stephen Dunn. New and Selected Poems (1974-1994) W.W. Norton