Clancy Tucker's Blog, page 188

May 11, 2017

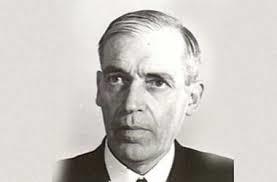

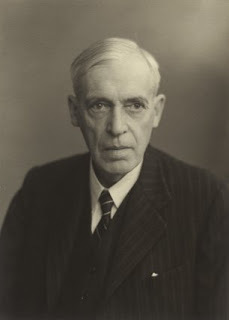

12 May 2017 - SIR OWEN DIXON

SIR OWEN DIXON

G'day folks,

Welcome to some background on an outstanding Australian. Sir Owen Dixon OM GCMG QC was an Australian judge and diplomat who served as the sixth Chief Justice of Australia.

Sir Owen Dixon (1886-1972), judge, was born on 28 April 1886 at Hawthorn, Melbourne, only son of Joseph William Dixon, barrister, and his wife Edith Annie, née Owen, both from Yorkshire, England. Because of deafness Joseph left the Bar and formed a partnership as a solicitor with one of his brothers. Owen was later to say that it 'was not easy' being brought up in a deaf man's house. He was, nevertheless, fond of his father and as a young barrister would discuss cases with him, standing face to face, his arms around his father's shoulders, his legs slightly apart and his mouth close to his father's ear, both men rocking from side to side as they talked.

The family had little money to spare, largely as a result of Joseph's ill health and some unsuccessful investments. Educated principally at Hawthorn College, Owen won a number of prizes and did well in his matriculation examinations. While the other boys admired him for his academic attainments, he was not popular as games-players were; his main sporting achievement was in rifle-shooting.

Dixon attended the University of Melbourne (B.A., 1906; LL.B., 1908; M.A., 1909) where he did not distinguish himself as a scholar, perhaps because he was interested in learning for learning's sake rather than for passing exams. He was influenced by professors (Sir) Harrison Moore and Thomas George Tucker:he obtained from Moore 'a complete grasp of legal principle . . . and a lively interest in constitutional and legal development'; from Tucker he acquired 'a love of classical literature and a sympathy with classical thought that affected the cast of his mind'.

It was due to Dixon's schooling in the classics that his 'passion for exactness in thought and expression was accompanied by a consciousness of fallibility'. These studies constituted the grounding of his later style of writing which displayed elegance and a mastery of the English language and the law. Of Dixon in his university days, a contemporary said that 'he possessed a soundness of judgement that was surprising . . . My own recollection of him is one of laughing indolence, which did not preclude an almost uncanny exactness of knowledge. I believe that what he once read he never forgot'.

Admitted to the Bar on 1 March 1910, Dixon took rooms in Selborne Chambers. He was unable to read with anyone because of his family's poor financial circumstances. In his early years he was one of the barristers commissioned by (Sir) Leo Cussen to work on the consolidation of Victorian statutes. While a junior, Dixon took three pupils—(Sir) Robert Menzies, (Sir) Henry Baker and (Sir) James Tait.

On 8 January 1920 at St Paul's Anglican Cathedral, Melbourne, Dixon married Alice Crossland Brooksbank (d.1971). He was greatly attached to his wife and kept in constant contact with her when they were apart. They had four children: Franklin Owen ('Bruv'), born in 1922, who suffered from conical cornea; Edward Owen ('Ted'), Elizabeth Brooksbank Owen ('Bett') and Anne Helen Owen, born in 1934. Dixon led a relatively simple life. He enjoyed horse-riding and—especially with his family—cycling and walking; he was a member of the Wallaby Club (president 1936). He also read avidly and widely. In keeping with his style of life, he disapproved of divorce, and was a teetotaller which stemmed from a promise he had made to his mother because of his father's heavy drinking.

Appointed K.C. in 1922, Dixon came to exercise 'absolute dominance' over the Bar. He was its 'acknowledged leader', 'its outstanding lawyer and its greatest advocate'. A tall, loose-jointed figure with somewhat stooped shoulders, he had a reputation for advocacy of 'calculated flippancy'. He was immensely effective, particularly in the High Court of Australia where he frequently appeared in both constitutional and non-constitutional matters; he 'set one judge against another', skilfully isolating a minority opposed to his point of view and 'persuading a majority to decide in his favour'. Before a jury, however, he was 'too intellectual' and did not shine at cross-examination.

Dixon worked prodigiously hard at the Bar, but enjoyed it enormously. He appeared on a number of occasions before the Privy Council. Sir John (Viscount) Simon, K.C., was so impressed with him that he 'suggested that he should take chambers in London and practise at the English Bar'. In 1928 Dixon was one of three barristers appointed by the committee of counsel for Victoria to present its submissions to the royal commission on the Constitution.

In July-December 1926 he had served as an acting-judge of the Supreme Court of Victoria. He refused to take a permanent post, possibly due to his opposition to hanging, a punishment which he regarded as barbaric. That year the Federal attorney-general (Sir) John Latham offered him the position of chief judge on the Commonwealth Court of Conciliation and Arbitration, but he declined. On 4 February 1929 Dixon was appointed to the High Court. At 42, he was the youngest member of the bench. He later said that he had accepted the post 'because I was told I ought'.

Throughout his career on the bench Dixon was to maintain that he disliked judicial work, saying that no one could get any pleasure out of it, and that it was hard and unrewarding. Part of his unhappiness arose from relationships between members of the High Court which were initially far from harmonious. Antagonism was eased in 1950 with the appointments of (Sir) Frank Kitto and (Sir) Wilfred Fullagar. Dixon liked both of them and particularly respected Fullagar. The court became a more congenial place in which to work.

Dixon had been on board a ship, returning from an overseas visit to seek treatment for Franklin's eyes, when war was declared in September 1939. On arriving in Australia, he told Prime Minister Menzies that he was 'anxious to do anything [he] could for the war', although he was to say in retrospect that he was not sure it was appropriate for a judge to do other work while holding office. Dixon chaired the Central Wool Committee (1940-42), the Shipping Control Board (1941-42), the Commonwealth Marine War Risks Insurance Board (1941-42), the Salvage Board (1942) and the Allied Consultative Shipping Council (1942). He displayed marked skill as an administrator and, after he had resigned from these bodies, was still consulted informally about their work. While engaged in this extrajudicial activity, he continued to sit on the bench, though he did less court work than previously. He had been appointed K.C.M.G. in 1941.

In April 1942 Sir Owen was chosen to succeed Richard Gavin (Baron) Casey as Australian minister in Washington. Dixon accepted the position only after pressure was exerted by Prime Minister John Curtin who argued that he could thereby make a more significant contribution to winning the war. As minister, Dixon was required to carry out the normal duties of the head of a diplomatic mission, but his major task was to ensure that the United States of America did not lose sight of the war in the Pacific and that Australia's interests were not neglected. He also represented Australia on the Pacific War Council and, later, on the council of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration.

Although Dixon was somewhat Anglophile and disliked many things American, he was able slowly to increase his influence in the U.S.A. and to earn respect. He came to admire individual Americans, such as General George C. Marshall, the army chief of staff, Dean Acheson, the assistant-secretary of state, and Justice Felix Frankfurter. On Dixon's departure from Washington, Marshall and Acheson were to speak warmly of him. Acheson described him as a person who would 'adorn' the Supreme Court of the United States 'if it were possible to appoint him to it'. He added that Dixon 'would be greatly missed in Washington where he had made himself ''beloved"'.

Dixon's job in Washington was made much harder by the minister for external affairs Bert Evatt who had sat with him on the High Court. Dixon disliked Evatt whom he regarded as politically motivated and a poor judge; he had no wish to work again with him. For his part, Evatt had not supported Dixon's appointment to Washington. Accordingly, Dixon had made it a condition of his accepting the post that he would be responsible not to Evatt but directly to the prime minister. Dixon confirmed the arrangement with Curtin on a visit to Australia in 1943. At his own request Dixon was relieved of his post in September 1944. The ostensible reason given was that victory for the Allies was certain and it was therefore proper for him to resume his judicial duties. In fact, the main cause of his wanting to return to Australia was the frustration he felt at Evatt's persistent interference and general conduct.

In 1950 Dixon was nominated as United Nations representative to mediate in the dispute between India and Pakistan over the State of Jammu and Kashmir. Later, he said that he had agreed to the appointment on the misunderstanding that it was to be a Commonwealth, rather than a U.N., operation. He considered the U.N. to be at best of no use, and at worst a danger, to British interests.

Reaching New Delhi in May 1950, Dixon travelled through the disputed territory to collect information, and on 20 July met jointly with prime ministers Jawaharlal Nehru of India and Liaqat Ali Khan of Pakistan. Dixon believed that the problem could only be solved by partitioning the region, but he was hampered by a U.N. Security Council decision to adhere to a plebiscite as the solution. At a series of meetings he advanced proposals to resolve the conflict, the last of which was that a plebiscite should be held in a limited area including the Kashmir Valley and that the rest of the State should be partitioned. India would not agree to take the preliminary steps necessary to ensure that the plebiscite would be a free and fair one. Dixon blamed Nehru for the impasse, observing that his 'strained arguments . . . are characteristic of a man instinctively aware that he is taking up an untenable position and not very proud of it'. None the less, in his report to the Security Council on 15 September Dixon reproached both sides for not reaching agreement.

Despite the failure of his mission, Dixon earned praise from the parties for his efforts. It was said that the qualities he brought to his role as mediator were 'his superb intellectual penetration and his capacity, strengthened over the years at the Bar and on the Bench, to seize on the heart of a complicated issue. Combined with that was his judicious spirit (some of his critics thought too judicious)'. By October he was back on the High Court bench.

Dixon employed the common law method in his judgements with rare skill and with faith in the capacity of its reasoning processes to reach just and correct solutions to legal problems. He took the view that there was 'no other safe guide to judicial decisions in great conflicts than a strict and complete legalism'. It is legalism, in the sense of the 'strict logic and high technique' of the common law, which permeates his judgements. In particular, he considered it essential that the common law method should be applied to the construction of the Commonwealth Constitution in order to maintain public confidence in the court's judgements as apolitical.

Consistent with his endorsement of the common law method, Dixon believed that the doctrine of precedent was of paramount importance. He remained committed to the principle that in general judges should proceed upon the basis that they inherit and develop the corpus juris, but do not make it afresh. He deplored 'the conscious judicial innovator' who 'is bound under the doctrine of precedents by no authority except the error he committed yesterday'. His adherence to precedent is to be seen most clearly in the transport cases decided under section 92 of the Constitution over a period of some twenty years. In the course of this line of cases he bowed to the view of the majority from which he had initially dissented. He was subsequently able to dissent again in McCarter v. Brodie (1950) on the basis of the Privy Council's decision in the Banking case (1949), but followed the majority in McCarter v. Brodie when he passed judgement on Hughes & Vale Pty Ltd v. State of New South Wales (1953). On appeal, the Privy Council adopted the reasons Dixon had given in dissent, principally in McCarter v. Brodie, and expressed much of its judgement in Dixon's own language.

Yet, Dixon's regard for the doctrine of precedent did not prevent him from refining, confining or extending the law in accordance with the common law method. While he accepted the decision of the court in the Engineers' case (1920), his dissatisfaction with the theoretical basis of that decision was shown in the way in which he applied the case more narrowly than others. He admitted that the Engineers' case 'is one that I have always applied with restraint'.

Further, Dixon held that the High Court, as a court of final resort, had a duty to expound the law correctly. The court was not compelled to follow decisions of the House of Lords or of itself where they were manifestly incorrect.

Moreover, he never shirked a decision which reason or principle required, as is demonstrated by the Communist Party case (1951) which involved the validity of the Communist Party Dissolution Act (1950). Dixon was strongly anti-communist and devoted a great deal of time to considering the case, 'much of it . . . in vain attempts to construct arguments in favour of [the] validity [of the Act] which would hold water'. For all that, he decided with the majority that the Act was invalid. Latham dissented and showed Dixon a draft of his judgement; Dixon wrote '[i]t sickened me with its abnegation of the function of the Court and I said so'.

Appointed chief justice on 18 April 1952, Dixon was sworn in three days later. He was 66 and was to hold office for twelve years. His appointment was universally acclaimed. Many thought that he was the greatest judicial lawyer in the English-speaking world; others regarded him as the most distinguished living exponent of the common law. His judgements carried persuasive effect wherever the common law was applied. An English judge, Baron Wilberforce, wrote: 'There is no such thing as substandard Dixon, but from time to time there is Dixon at his superb best'. Dixon's pre-eminence had been recognized by his appointment to the Privy Council in 1951 (although he chose not to sit on it) and by his numerous honours and awards. He was elevated to G.C.M.G.

in 1954 and was appointed to the Order of Merit in 1963. Honorary degrees were conferred upon him by the universities of Oxford (D.C.L., 1958), Harvard (LL.D., 1958), Melbourne (LL.D., 1959) and the Australian National University (LL.D., 1964). In 1955 Yale University had awarded him the Harry E. Howland memorial prize 'for services to mankind' and in 1970 he became a corresponding fellow of the British Academy. The degrees from Oxford and Harvard gave him particular pleasure.

Dixon was a witty and engaging conversationalist. He tended to speak unconsciously in epigrams and his descriptions of his contemporaries could be telling. Renowned for his sense of humour, he could handle the most serious matters with an extraordinarily light touch. Working with him was likely to be punctuated by his peals of laughter, often provoked by the revelation of some human foible that delighted him. In court his sense of humour was restrained, but in conversation he took pleasure in the intellectual joke; he found in the law and lawyers an inexhaustible source of enjoyment. Dixon did have faults. He was rather vain, although he did not wear his vanity openly. In addition, he could be a little pretentious, parading his learning in languages before others who were not so knowledgeable. On the other hand, it has been said of him that he had the 'knowledge and urbanity to be able to talk without any thought of showing off and the grace to assume that others would naturally converse in the same way'. He liked gossip, but in relating the failings of others he showed amusement, not malice.

As chief justice, Dixon defended the integrity and independence of the High Court with vigour. He staunchly opposed suggestions that it should move to Canberra. Indeed, he opposed the court having a permanent seat anywhere because he thought it should not be removed from the people, the judges or the legal profession; he considered that it should be 'an all-Australian Court, going to the people rather than requiring the people to come to it'.

In the early 1960s Dixon's health deteriorated and there was a reduction in both the number of judgements that he wrote and the number of cases on which he sat. On 13 April 1964 he retired. He said that he was doing so 'because I believe I ought', and went on to observe: 'I am not one of those who subscribe to the view that the older you get the better you get . . . I believe in young everything. I thought that I had got too old and was deeply conscious of the fact that I was not doing my work adequately'. Following his retirement he took no part in public life. Asked whether he would allow himself to be nominated for the office of governor-general, he refused, and Casey was appointed. S. H. Z. Woinarski's collection of Dixon's papers and addresses, Jesting Pilate(Sydney), was published in 1965.

Dixon's poor health persisted and he was confined for most of his remaining life to his home at Hawthorn, for some considerable part of that time to his chair. As Sir Owen's eyesight failed, his son Franklin read aloud to him. Survived by his children, Dixon died on 7 July 1972 at his home and was buried in Boroondara cemetery. His portrait by Archibald Colquhoun is in the High Court, Canberra.

Clancy's comment: A sharp man with an even sharper career.

I'm ...

Published on May 11, 2017 15:04

May 10, 2017

11 May 2017 - TRICKY WORDS TO MASTER

TRICKY WORDS TO MASTER

G'day folks,

Welcome to some more words that seem to cause us grief. English vocabulary is full of pitfalls that you might not be aware of. Don't let them trip you up.

INVARIABLY

If something happens invariably, it always happens. To be invariable is to never vary. The word is sometimes used to mean frequently, which has more leeway.

COMPRISE/COMPOSE

A whole comprises its parts. The alphabet comprises 26 letters. The U.S. comprises 50 states. But people tend to say is comprised of when they mean comprise. If your instinct is to use the is … of version, then substitute composed. The whole is composed of its parts.

FREE REIN

The words rein and reign are commonly confused. Reign is a period of power or authority—kings and queens reign—and a good way to remember it is to note that the g relates it to royal words like regent and regal. A rein is a strap used to control a horse. The confusion comes in when the control of a horse is used as a metaphor for limits on power or authority. Free rein comes from such a metaphor. If you have free rein you can do what you want because no one is tightening the reins.

JUST DESERTS

There is only one s in the desert of just deserts. It is not the dessert of after-dinner treats nor the dry and sandy desert. It comes from an old noun form of the verb deserve. A desert is a thing which is deserved.

TORTUOUS/TORTUROUS

Tortuous is not the same as torturous. Something that is tortuous has many twists and turns, like a winding road or a complicated argument. It’s just a description. It makes no judgment on what the experience of following that road or argument is like. Torturous, on the other hand, is a harsh judgment—“It was torture!”

EFFECT/AFFECT

When you want to talk about the influence of one thing on another, effect is the noun and affect is the verb. Weather affects crop yields. Weather has an effect on crop yields. Basically, if you can put a the or anin front of it, use effect.

EXCEPT/ACCEPT

People rarely use accept when they mean except, but often put exceptwhere they shouldn’t. To accept something is to receive, admit, or take on. To except is to exclude or leave out—“I’ll take all the flavors except orange.” The x in except is a good clue to whether you’ve got it right. Are you xing something out with the word? No? Then consider changing it.

DISCREET/DISCRETE

Discreet means hush-hush or private. Discretemeans separate, divided, or distinct. In discreet, the two Es are huddled together, telling secrets. In discrete, they are separated and distinguished from each other by the intervening t.

I.E./E.G.

When you add information to a sentence with parentheses, you’re more likely to need e.g., which means “for example,” than i.e., which means “in other words” or “which is to say ...” An easy way to remember them is that e.g. is eg-zample and i.e. is “in effect.”

DISINTERESTED/UNINTERESTED

People sometimes use disinterested when they really mean uninterested. To be uninterested is to be bored or indifferent to something; this is the sense most everyday matters call for. Disinterested means impartial or having no personal stake in the matter. You want a judge or referee to be disinterested, but not necessarily uninterested.

Clancy's comment: Another bunch to print off and stick on your wall ... Just in case.

I'm ...

Published on May 10, 2017 16:55

May 9, 2017

10 May 2017 - TOP QUOTES TO READ

TOP QUOTES TO READ

G'day folks,

Time for some interesting quotes that might be worth reading.

Clancy's comment: Yep, at the end of the day it's your choice.

I'm ...

Published on May 09, 2017 14:06

May 8, 2017

9 May 2017 - MOVING PICTURES

MOVING PICTURES

G'day folks,

Welcome to another set of rolling photos.

Clancy's comment: I love the moving eyes and corgi best.

I'm ...

Published on May 08, 2017 14:42

May 7, 2017

8 May 2017 - MALCOLM X

MALCOLM X

G'day folks,

African-American leader and prominent figure in the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X articulated concepts of race pride and black nationalism in the 1950s and '60s.

Synopsis

Born on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska, Malcolm X was a prominent black nationalist leader who served as a spokesman for the Nation of Islam during the 1950s and '60s. Due largely to his efforts, the Nation of Islam grew from a mere 400 members at the time he was released from prison in 1952 to 40,000 members by 1960. Articulate, passionate and a naturally gifted and inspirational orator, Malcolm X exhorted blacks to cast off the shackles of racism "by any means necessary," including violence. The fiery civil rights leader broke with the group shortly before his assassination on February 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom in Manhattan, where he had been preparing to deliver a speech.

Early Life Malcolm X was born Malcolm Little on May 19, 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska. Malcolm was the fourth of eight children born to Louise, a homemaker, and Earl Little, a preacher who was also an active member of the local chapter of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and avid supporter of black nationalist leader Marcus Garvey. Due to Earl Little's civil rights activism, the family was subjected to frequent harassment from white supremacist groups including the Ku Klux Klan and one of its splinter factions, the Black Legion. In fact, Malcolm X had his first encounter with racism before he was even born.

"When my mother was pregnant with me, she told me later, 'a party of hooded Ku Klux Klan riders galloped up to our home,'" Malcolm later remembered. "Brandishing their shotguns and rifles, they shouted for my father to come out." The harassment continued when Malcolm X was four years old, and local Klan members smashed all of the family's windows. To protect his family, Earl Little moved them from Omaha to Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1926 and then to Lansing, Michigan in 1928.

However, the racism the family encountered in Lansing proved even greater than in Omaha. Shortly after the Littles moved in, in 1929, a racist mob set their house on fire, and the town's all-white emergency responders refused to do anything. "The white police and firemen came and stood around watching as the house burned to the ground," Malcolm X later remembered. Earl Little moved the family to East Lansing where he built a news home.

Two years later, in 1931, Earl Little's dead body was discovered lying across the municipal streetcar tracks. Although Malcolm X's family believed his father was murdered by white supremacists from whom he had received frequent death threats, the police officially ruled Earl Little's death a a streetcar accident, thereby voiding the large life insurance policy he had purchased in order to provide for his family in the event of his death. Malcolm X's mother never recovered from the shock and grief over her husband's death. In 1937, she was committed to a mental institution where she remained for the next 26 years. Malcolm and his siblings were separated and placed in foster homes.

In 1938, Malcolm X was kicked out of school and sent to a juvenile detention home in Mason, Michigan. The white couple who ran the home treated him well, but he wrote in his autobiography that he was treated more like a "pink poodle" or a "pet canary" than a human being. He attended Mason High School where he was one of only a few black students. He excelled academically and was well liked by his classmates, who elected him class president.

A turning point in Malcolm X's childhood came in 1939, when his English teacher asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up and he answered that he wanted to be a lawyer. His teacher responded, "One of life's first needs is for us to be realistic. . .you need to think of something you can be. . .why don't you plan on carpentry?" Having thus been told in no uncertain terms that there was no point in a black child pursuing education, Malcolm X dropped out of school the following year, at the age of 15.

After quitting school, Malcolm X moved to Boston to live with his older half-sister, Ella, about whom he later recalled, "She was the first really proud black woman I had ever seen in my life. She was plainly proud of her very dark skin. This was unheard of among Negroes in those days." Ella landed Malcolm a job shining shoes at the Roseland Ballroom. However, out on his own on the streets of Boston, Malcolm X became acquainted with the city's criminal underground, soon turning to selling drugs.

He got another job as kitchen help on the Yankee Clipper train between New York and Boston and fell further into a life of drugs and crime. Sporting flamboyant pinstriped zoot suits, he frequented nightclubs and dance halls and turned more fully to crime to finance his lavish lifestyle. This phase of Malcolm X's life came to a screeching halt in 1946, when he was arrested on charges of larceny and sentenced to ten years in jail.

To pass the time during his incarceration, Malcolm X read constantly, devouring books from the prison library in an attempt make up for the years of education he had missed by dropping out of high school. Also while in prison, he was visited by several siblings who had joined to the Nation of Islam, a small sect of black Muslims who embraced the ideology of black nationalism—the idea that in order to secure freedom, justice and equality, black Americans needed to establish their own state entirely separate from white Americans. Malcolm X converted to the Nation of Islam while in prison, and upon his release in 1952 he abandoned his surname "Little," which he considered a relic of slavery, in favor of the surname "X"—a tribute to the unknown name of his African ancestors.

Nation of Islam Now a free man, Malcolm X traveled to Detroit, Michigan, where he worked with the leader of the Nation of Islam, Elijah Muhammad, to expand the movement's following among black Americans nationwide. Malcolm X became the minister of Temple No. 7 in Harlem and Temple No. 11 in Boston, while also founding new temples in Harford and Philadelphia. In 1960, he established a national newspaper, Muhammad Speaks, in order to further promote the message of the Nation of Islam.

Articulate, passionate and a naturally gifted and inspirational orator, Malcolm X exhorted blacks to cast off the shackles of racism "by any means necessary," including violence. "You don't have a peaceful revolution," he said. "You don't have a turn-the-cheek revolution. There's no such thing as a nonviolent revolution." Such militant proposals—a violent revolution to establish an independent black nation—won Malcolm X large numbers of followers as well as many fierce critics. Due primarily to the efforts of Malcolm X, the Nation of Islam grew from a mere 400 members at the time he was released from prison in 1952, to 40,000 members by 1960.

By the early 1960s, Malcolm X had emerged as a leading voice of a radicalized wing of the Civil Rights Movement, presenting an alternative to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s vision of a racially integrated society achieved by peaceful means. Dr. King was highly critical of what he viewed as Malcolm X's destructive demagoguery. "I feel that Malcolm has done himself and our people a great disservice," King once said.

Philosophical differences with King were one thing; a rupture with Elijah Muhammad proved much more traumatic. In 1963, Malcolm X became deeply disillusioned when he learned that his hero and mentor had violated many of his own teachings, most flagrantly by carrying on many extramarital affairs; Muhammad had, in fact, fathered several children out of wedlock. Malcolm's feelings of betrayal, combined with Muhammad's anger over Malcolm's insensitive comments regarding the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, led Malcolm X to leave the Nation of Islam in 1964.

That same year, Malcolm X embarked on an extended trip through North Africa and the Middle East. The journey proved to be both a political and spiritual turning point in his life. He learned to place the American Civil Rights Movement within the context of a global anti-colonial struggle, embracing socialism and pan-Africanism. Malcolm X also made the Hajj, the traditional Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, during which he converted to traditional Islam and again changed his name, this time to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

After his epiphany at Mecca, Malcolm X returned to the United States less angry and more optimistic about the prospects for peaceful resolution to America's race problems. "The true brotherhood I had seen had influenced me to recognize that anger can blind human vision," he said. "America is the first country ... that can actually have a bloodless revolution." Tragically, just as Malcolm X appeared to be embarking on an ideological transformation with the potential to dramatically alter the course of the Civil Rights Movement, he was assassinated.

Death and Legacy On the evening of February 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom in Manhattan, where Malcolm X was about to deliver a speech, three gunmen rushed the stage and shot him 15 times at point blank range. Malcolm X was pronounced dead on arrival at Columbia Presbyterian Hospital shortly thereafter. He was 39 years old. The three men convicted of the assassination of Malcolm X were all members of the Nation of Islam: Talmadge Hayer, Norman 3X Butler and Thomas 15X Johnson.

In the immediate aftermath of Malcolm X's death, commentators largely ignored his recent spiritual and political transformation and criticized him as a violent rabble-rouser. However, Malcolm X's legacy as a civil rights hero was cemented by the posthumous publication in 1965 of The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley. At once a harrowing chronicle of American racism, an unsparing self-criticism and an inspiring spiritual journey, the book, transcribed by the acclaimed author of Roots, instantly recast Malcolm X as one of the great political and spiritual leaders of modern times. Named by TIMEmagazine one of 10 "required reading" non-fiction books of all-time, The Autobiography of Malcolm X has truly enshrined Malcolm X as a hero to subsequent generations of radicals and activists.

Perhaps Malcolm X's greatest contribution to society was underscoring the value of a truly free populace by demonstrating the great lengths to which human beings will go to secure their freedom. "Power in defense of freedom is greater than power in behalf of tyranny and oppression," he stated. "Because power, real power, comes from our conviction which produces action, uncompromising action."

In 1958, Malcolm X married Betty Sanders, a fellow member of the Nation of Islam. The couple had six children together, all daughters: Attallah (b. 1958), Qubilah (b. 1960), Ilyasah (b. 1963), Gamilah (b. 1964) and twins Malaak and Malikah (b. 1965). Sanders later became known as Betty Shabazz, and she became a prominent civil rights and human rights activist in her own right in the aftermath of her husband's death.

In May 2013, Malcolm X's grandson, Malcolm Shabazz—son of the civil rights leader's second daughter with wife Betty Shabazz, Qubilah Shabazz—was beaten to death in Mexico City, near the Plaza Garibaldi. He was 28 years old. According to a report by the Los Angeles Times, police believe Malcolm Shabazz's death was the result of a "robbery gone wrong."

Clancy's comment: Another interesting and influential man in history who died early.

I'm ...

Published on May 07, 2017 14:44

May 6, 2017

7 May 2017 - BABY BIG CATS

BABY BIG CATS

G'day folks,

Welcome to some cute pictures of baby big cats, courtesy of National Geographic. Check out the paws, teeth and eyes.

Clancy's comment: Mm ... Brilliant photography, eh?

I'm ...

Published on May 06, 2017 15:41

May 5, 2017

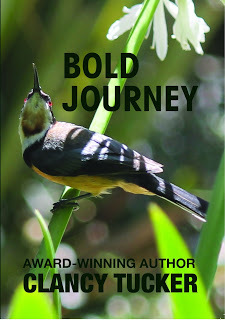

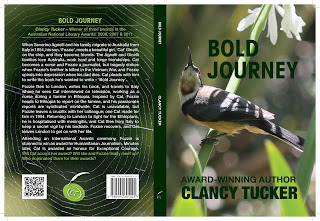

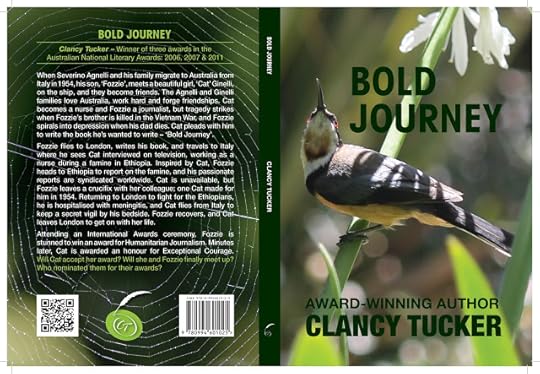

6 May 2017 - GREAT REVIEW FOR 'BOLD JOURNEY'

GREAT REVIEW FOR'BOLD JOURNEY'

G'day folks,I am pleased to present a top review of my latest book - Bold Journey; just released on Buzzwords Magazine. The review has been written by one of Australia's best book reviewers, Anastasia Gonis.

WHAT IS BUZZ WORDS:

Buzz Words is for writers and illustrators of children's and YA books, as well as librarians, teachers, editors and publicists. Buzz Words is a fortnightly e-zine with valuable information on markets, opportunities competitions, courses, conferences and book reviews for those writing for children. It also features writing tips and interviews. And it's delivered straight into your in-box!

Now, for the review ...

Bold Journey by Clancy Tucker (Clancy Tucker Publishing)

PB RRP $15.00 plus $3.00 for postage Australia

ISBN 9780994601025

Reviewed by Anastasia Gonis

The story begins in 1954, when the Agnelli family set out for Australia on an Assisted Migrant Scheme. The positives and negatives of their decision are cleverly woven into a delicate and moving story of migration, with themes of friendship, family, bullying, and the huge impact the kindness and generosity of strangers can have on people’s lives.

Cat Ginelli and ‘Fozzie’ Agnelli have been friends since childhood after meeting on the ship. Their years of friendship, togetherness, learning, discovery, and shared grief, is slowly transformed into something powerful, but unspoken. While life leads them along different and distant paths as they grow, the emotional ties between them remain unbroken.

Will they finally come together at the official function put on by Amnesty International, or will the story of their life together end due to those words unspoken?

The struggles and challenges the Agnelli family face are the struggles of every migrant family of the post-war years. The courage and determination of they have to adapt and succeed reflect the characteristics of migrants of that era, and many of those of today.

Through his work, Clancy again seizes the opportunity to bring into focus, issues that he is passionate about. He addresses the humanitarian need of countries ravaged by war and poverty, with the intention that it will ‘stir the conscience’ of his readers, and the world in general. He makes reference to the Vietnam and Korean wars and their futility in a significant way.

This is an interesting and well-constructed novel which is historically valuable, in that it reflects on the how and why, Europeans left their homelands for a better life, what they found, and what they did with what they had.

Clancy Tucker has created lovable characters and moving scenes. He has presented a wide view of migrant life. All this is folded into a story of love, hope and sacrifice. Suited for ages 8-80, it also shows the multi-faceted lives of post-war Australians through dialogue, varying voices and points of view.

I'd highly recommend any authors check out Buzz Words Magazine. Here is the link:

BUZZ WORDS MAGAZINE

Clancy's comment: Many thanks to Anastasia Gonis and Buzz Words for supporting authors. Love ya work! So, folks, if you are keen to read this book, just head up to the right-hand side of this page where you can purchase a signed paperback or e-Book.

I'm ...

Published on May 05, 2017 15:24

May 4, 2017

5 May 2017 - DESERTS

DESERTS

G'day folks,

Australia is supposedly the driest continent on earth, but what is a desert? A desert is a barren area of land where little precipitation occurs and consequently living conditions are hostile for plant and animal life. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to the processes of denudation. Here are some more detailed facts.

Basic Facts About Deserts

Deserts are found across our planet along two fringes parallel to the equator at 25–35° latitude in both the northern and southern hemispheres. Deserts are arid or dry regions and receive less than 10 inches of rain per year.

Biologically, they contain plants and animals adapted for survival in arid environments. Physically they are large areas with a lot of bare soil and low vegetation cover. The world’s deserts occupy almost one-quarter of the earth’s land surface, which is approximately 20.9 million square miles.

The Mojave Desert is so diverse that it is subdivided into five regions: northern, south-western, central, south-central, and eastern. Elevations range from below sea level at Death Valley National Park to 2.26 miles on Mt. Charleston in the Spring Range of Nevada.

Deserts receive little rainfall, however, when rain does fall, the desert experiences a short period of great abundance. Plants and animals have developed very specific adaptations to make use of these infrequent short periods of great abundance.

Desert Formation

Deserts landscapes are more diverse than many expect. Some are found on a flat shield of ancient crystalline rocks hardened over many millions of years, yielding flat deserts of rock and sand such as the Sahara. Others are the folded product of more recent tectonic movements, and have evolved into crumpled landscapes of rocky mountains emerging from lowland sedimentary plains, as in Central Asia or North America .

Hot and dry deserts

Hot and dry desertsThe hottest type of desert, with parched terrain and rapid evaporation. In the hot and dry desert soils are course-textured, shallow, rocky or gravely with good drainage and have no subsurface water. They are coarse because there is less chemical weathering. The finer dust and sand particles are blown elsewhere, leaving heavier pieces behind.

Cool coastal deserts

These deserts are located within the same latitudes as subtropical deserts, yet the average temperature is much cooler because of frigid offshore ocean current. In the coastal desert the soil is fine-textured with a moderate salt content. It is fairly porous with good drainage.

Semi arid deserts

Polar regions are also considered to be deserts because nearly all moisture in these areas is locked up in the form of ice.

Desert PlantsMost desert species have found remarkable ways to survive by evading drought. Desert succulents, such as cacti or rock plants (Lithops) for example, survive dry spells by accumulating moisture in their fleshy tissues. They have an extensive system of shallow roots to capture soil water only a few hours after it has rained. Additionally, many cacti and other stem-succulent plants of hot deserts present columnar growth, with leafless, vertically-erect, green trunks that maximize light interception during the early and late hours of the day, but avoid the midday sun, when excessive heat may damage plant tissues.

One of the most effective drought-survival adaptations for many species is the evolution of an ephemeral life-cycle. An ephemeral life cycle is characterized by a short life and the capacity to leave behind very hardy forms of propagation. This ability is found not only in plants but also in many invertebrates. Desert ephemerals are amazingly rapid growers capable of reproducing at a remarkably high rate during good seasons.

Animals

Birds and large mammals can escape critical dry spells by migrating along the desert plains or up into the mountains. Smaller animals cannot migrate but regulate their environment by seeking out cool or shady places. In addition to flying to other habitats during the dry season, birds can reduce heat by soaring. Many rodents, invertebrates, and snakes avoid heat by spending the day in caves and burrows searching out food during the night. Animals active in the day reduce their activities by resting in the shade during the hotter hours.

Clancy's comment: It amazes me how animals and plants survive in such places. Certainly not a place to be lost.

I'm ...

Published on May 04, 2017 14:55

May 3, 2017

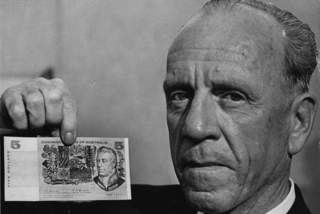

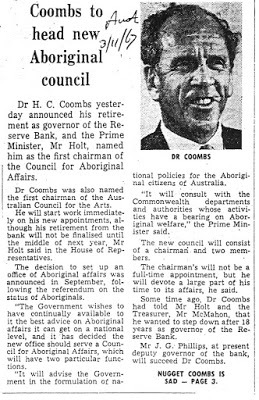

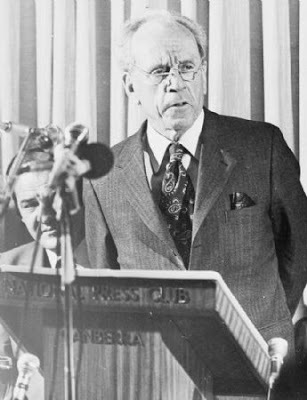

4 May 2017 - Herbert Cole Coombs (Nugget) (1906–1997)

Herbert Cole Coombs (Nugget) (1906–1997)

G'day folks,

Welcome to some background on another exceptional Australian.

Following his term as the Chancellor of ANU, Dr Herbert Cole Coombs concluded that a Visiting Fellowship could provide the necessary home base and stimulating intellectual environment for the next phase of his life's work. After discussions with Professor Frank Fenner, the founding Director of the newly established Centre for Resource and Environmental Studies (CRES), Dr Coombs was formally appointed a Visiting Fellow there in May, 1976.

Nugget, as he was universally and affectionately known, became a vital and valued member of the CRES community, from the time it moved into its quarters in the new Life Sciences Library (now Hancock) Building in late 1976 until late 1995 when a stroke prevented his return to Canberra for the summer.

The Institute of Advanced Studies in ANU, to which CRES belongs, has well established policies on the appointment of retired persons as Visiting Fellows.

Only in exceptional circumstances, where the appointee is engaged in academic work of particular note, may the period of appointment be extended from an initial two years, to a further two years and then a final fifth year. Then, if the Research School or Centre is satisfied that there would be continuing academic benefit of a high order in continuing the appointment for a further year, it must seek the approval of the Vice Chancellor for the extension. This was the basis for the continuing extension of Nugget's Visiting Fellowship from 1976 through to 1996.

Let me emphasise that this was never a sinecure or a reward for his previous distinguished contributions to Australian society. The long continued sequence of annual reappointments was always based on his current intellectual, cultural and social contributions to CRES and ANU.

Nugget maintained a high level of productivity right up until his disabling stroke in late 1995. Even then, plans were in place for his return to CRES after recovery. Regrettably this was not to be. Hopes were high that he would be well enough to travel from Sydney to Canberra for a combined 90th birthday celebration and presentation, by the Vice-Chancellor, of his Distinguished 50th Anniversary Fellowship Award, on the 12th March, 1996. Unfortunately these hopes were dashed when his condition failed to improve.

This is not the place to detail Nugget's academic contributions, but the flow of books, essays, keynote addresses and key reports to government continued unabated right up to the last few months of 1995. Perhaps even more important were his contributions through undocumented, behind-the-scenes advice to key figures in Australian public life, from Prime Ministers, Cabinet Ministers, captains of industry, bankers and media-barons through to leaders of his cherished cultural, indigenous people and conservation associations.

Despite his well-earned image as a controlled, low-key, sagacious servant of the people, Nugget was passionate in his concern for natural justice and the welfare of the individual. This extended beyond the aboriginal causes for which he is best known. His anger at the social impacts of ill-informed and misguided political decisions rarely, if ever, descended to personal vilification. He never spoke ill of individuals whatever the provocation. This high level of emotional self-control could be, and was, breached on occasion: a great catch in a cricket test match or the first swirl of a sensuous Margaret River red on the palate, for instance.

Nugget genuinely loved people and mixed with ease among all levels of Australian society. He travelled light — and often. During his years in CRES his advocacy of aboriginal rights took him to the remotest parts of northern and inland Australia. These travels took him often to Darwin where he availed himself of the accommodation and excellent support facilities at the Northern Australian Research Unit (NARU) — an outpost of the Research School of Asian and Pacific Studies at ANU. Towards the end of the 1980s, Nugget began to find the Canberra winters more difficult to cope with because of a bronchial condition. I urged him to organise his work year so that he could spend the winter half-year in Darwin. In 1991 the arrangement was formalised so that his Visiting Fellowship was held jointly with CRES and NARU in the RSPAS. Nugget travelled north for the winter and returned south for the summer. This ideal arrangement favoured Nugget's health and well-being and proved to be highly productive.

The most enduring memory of Nugget is his humanity. His concern for the underdog and the disadvantaged never wavered. He remained unassuming and kept a low profile whatever the occasion. CRES staff and students profited greatly from his wit and wisdom at morning and afternoon tea in the CREStaurant on the fifth floor of the Hancock building. He played squash into his early 80s and starred in CRES cricket matches well beyond that.

He loved good food and wine and was a very fine cook. On one occasion, while dining with friends in his flat in Moore Street he had tabled one of his favourite Margaret River reds. The superb meal which Nugget had prepared and cooked, fine conversation and the outstanding Gnangara Shiraz led to the inevitable query from Nugget as to whether he should open another bottle.

The ladies demurred, but Nugget, with a flourish, uncorked another Gnangara and quoted, "moderation in all things"- and with a pause and a twinkle in his eye — "especially moderation".

Published on May 03, 2017 14:36

May 2, 2017

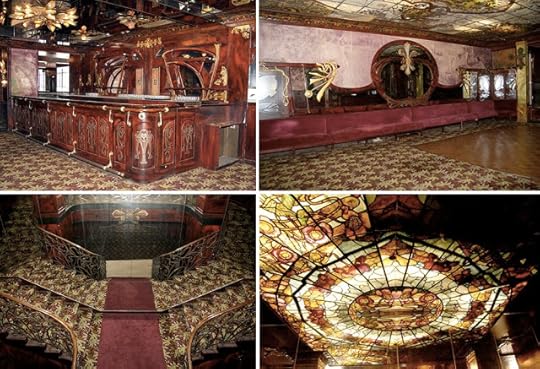

3 May 2017 - SAVED FROM DEMOLITION

SAVED FROM DEMOLITION

G'day folks,

Ever wondered what happens to the fittings inside buildings that are demolished? Well, some companies do purchase valuable items and sell them on to others. Here are some examples of things that have been saved from buildings in New York.

Clancy's comment: Most of the items depicted above were made by craftsman, and sadly, many of those skills have gone.

I'm ...

Published on May 02, 2017 14:52