Robert Rodi's Blog, page 8

December 17, 2011

Home news

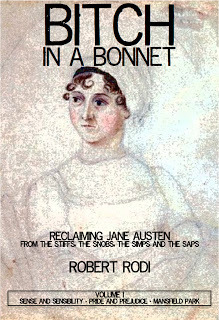

ITEM ONE: The first volume of the collected Bitch in a Bonnet (covering the first three novels in the Austen canon) is now available for Amazon's e-reader, Kindle, and Barnes & Noble's e-reader, Nook.

You might ask what would possess you to buy a copy of a text that's already available for free on this blog. Well...it's newly edited so all the typos and grammatical lapses are finessed out...it has a snazzy new cover...and—drumroll, please—it's just 99 cents.

That's right, 99 cents for three years and 300+ manuscript pages' worth of material. It's almost like getting it for free. Admit it, you've got more cash than that stuffed down behind your sofa cushions.

So tell your friends, tell your frenemies, tell everybody...the Bitch has gone commercial. And she's easy and she's cheap.

ITEM TWO: I'll be taking the holidays off and will resume blogging again in early 2012 with Emma. Merry Christmas, Happy Hanukah, Joyous Kwanzaa, and Happy New Year to you all. I'm glad we found each other and hope never to let go. (Which sounds vaguely frightening, but I mean it in the nicest way, honestly.)

ITEM THREE: I've had some complaints from readers who have been thwarted in their attempts to leave comments on the blog; so when I do return, it may be to a new blog server. But no worries, I'll be sure to notify you of the new location right here at the old one.

And while we're on the subject, should any of you have recommendations for where to take the blog, please let me know. (Or for that matter if any of you are strong advocates for keeping it right here on Blogger, speak up as well. I'm open to all advice, at this point.)

That's all for now. See you in 2012!

You might ask what would possess you to buy a copy of a text that's already available for free on this blog. Well...it's newly edited so all the typos and grammatical lapses are finessed out...it has a snazzy new cover...and—drumroll, please—it's just 99 cents.

That's right, 99 cents for three years and 300+ manuscript pages' worth of material. It's almost like getting it for free. Admit it, you've got more cash than that stuffed down behind your sofa cushions.

So tell your friends, tell your frenemies, tell everybody...the Bitch has gone commercial. And she's easy and she's cheap.

ITEM TWO: I'll be taking the holidays off and will resume blogging again in early 2012 with Emma. Merry Christmas, Happy Hanukah, Joyous Kwanzaa, and Happy New Year to you all. I'm glad we found each other and hope never to let go. (Which sounds vaguely frightening, but I mean it in the nicest way, honestly.)

ITEM THREE: I've had some complaints from readers who have been thwarted in their attempts to leave comments on the blog; so when I do return, it may be to a new blog server. But no worries, I'll be sure to notify you of the new location right here at the old one.

And while we're on the subject, should any of you have recommendations for where to take the blog, please let me know. (Or for that matter if any of you are strong advocates for keeping it right here on Blogger, speak up as well. I'm open to all advice, at this point.)

That's all for now. See you in 2012!

Published on December 17, 2011 07:58

October 27, 2011

Mansfield Park, chapters 46-48

We rejoin Fanny where we left her last time—where we appear to have left her for the last geologic age; the Price clan might have been hunting mastadons when she arrived—sitting at home, doing nothing except receiving letters. But wait…apparently she's not receiving letters. After she declined the Crawfords' offer to come and steal her away from Portsmouth, she expected to be battered with exhortations to change her mind. But nope…nothing. Until after the space of a week, something does come from Mary Crawford, so skimpy a missive that Fanny is "persuaded of its having the air of a letter of haste and business"—possibly announcing Mary's arrival, with Henry, in Portsmouth to carry her off in a shackles if need be.

But no; the letter is instead a strange, cryptic thing, urging Fanny to ignore a "most scandalous, ill-natured rumour" that's just come to Mary's ear, and assuring her that "Henry is blameless, and in spite of a moment's etouderie thinks of nobody but you."

I am sure it will all be hushed up, and nothing proved but Rushworth's folly. If they are gone, I would lay my life they are only gone to Mansfield Park, and Julia with them. But why would not you let us come for you? I wish you may not repent it.

Fanny is mystified. No scandalous, ill-natured rumour has reached her; in her little Portsmouth cocoon, it's a miracle if oxygen reaches her. "She could only perceive that it must relate to Wimpole Street and Mr. Crawford, and only conjecture that something very imprudent had just occurred in that quarter to draw the notice of the world," though why she should care whether the Rushworths then beat a hasty retreat, and where they went, and whether Julia was with them, is beyond her.

As to Mr. Crawford, she hoped it might give him a knowledge of his own disposition, convince him that he was not capable of being steadily attached to any one woman in the world, and shame him from persisting any longer in addressing herself.

Yes, that would be best. Leave Fanny to her little airless existence where the taint of inconvenient human feeling needn't disturb her inertia. Think I'm being too harsh?...Here's Fanny's own POV on the situation.

She felt that she had, indeed, been three months (in Portsmouth); and the sun's rays falling into the parlour, instead of cheering, made her still more melancholy; for sun-shine appeared to her a totally different thing in a town and in the country. Here, its power was only a glare, a stifling, sickly glare, serving to bring forward stains and dirt that might otherwise have slept. There was neither health nor gaiety in sunshine in a town. She sat in a blaze of oppressive heat, in a cloud of moving dust; and her eyes could only wander from the walls marked by her father's head, to the table cut and knotched by her brothers, where stood the tea-board never thoroughly cleaned, the cups and saucers wiped in streaks, the milk a mixture of motes floating in thin blue, and the bread and butter growing every minute more greasy than even Rebecca's hands had first produced it.

Killer bit of writing there, btw.

It's in this scene of domestic oblivion that the scandalous, ill-natured rumour finally reaches Fanny's ear, by the unlikeliest source imaginable: her boozy old man and his borrowed broadsheet. He looks up from its pages and says, "What's the name of your great cousins in town, Fan?" and when she answers Rushworth, and confirms they live on Wimpole Street, he's tickled pink.

"Then, there's the devil to pay among them, that's all. There, (holding out the paper to her)—much good may such fine relations do you. I don't know what Sir Thomas may think of such matters; he may be too much of the courtier and fine gentleman to like his daughter the less. But by G— if she belonged to me, I'd give her the rope's end as long as I could stand over her."

Which might not be too long, given that standing unassisted isn't exactly one of Mr. Price's superpowers. Still, the point is made: one of Sir Thomas's daughters has been extra-special naughty. Fanny takes up the paper and reads a report of "a matrimonial fracas in the family of Mr. R. of Wimpole Street," whose beautiful young bride (whose name "had not long been enrolled in the lists of hymen"—love that turn of phrase) has "quitted her husband's roof in the company of the well known and captivating Mr. C. …and it was not known, even to the editor of the newspaper, whither they were gone." Why the editor of the newspaper should be expected to know above anyone else, I'm not quite sure. Possibly he's a Regency Perry White or something.

Fanny insists that this is all a terrible mistake, even though she knows it's not. (Scarcely the first instance of Fanny deliberate obscuring the facts.) She speaks "from the instinctive wish of delaying shame," but she might have spared herself the trouble, because her father doesn't really give a good goddamn; now that he's scored a cheap point off her, he's fine just letting the whole thing drop. As for Fanny's mother, her reaction is hilariously typical.

"Indeed, I hope it is not true," said Mrs. Price plaintively; "it would be so very shocking!—If I have spoke once to Rebecca about that carpet, I am sure I have spoke at least a dozen times; have I not, Betsey?—And it would not be ten minutes work."

Fanny meanwhile retreats to do what Fanny does best, which is languish and brood. She torments herself by going over everything again and again and again, like someone stuck in a time loop, and coming to the same inevitable (and, I'm betting, secretly satisfying) conclusions, especially with regard to Mary Crawford.

Her eager defense of her brother, her hope of its being hushed up, her evident agitation, were all of a piece with something very bad; and if there was a woman of character in existence, who could treat as a trifle this sin of the first magnitude, who could try to gloss it over, and desire to have it unpunished, she could believe Miss Crawford to be the woman!

There's a lot of anguished reflection on how horrible, horrible, horrible it all is, to the point at which you begin to feel uncomfortable, like you're witnessing a sadomasochist wallowing in the sheer pleasure of acute agony. She spends an almost pornographic amount of time speculating on who will be most injured by the scandal, and decides Sir Thomas wins that particular prize, with Edmund the silver medalist, and in minutely considering their emotional devastation she works herself into a kind of melodramatic fit.

Sir Thomas's parental solicitude, and high sense of honour and decorum, Edmund's upright principles, unsuspicious temper, and genuine strength of feeling, made her think it scarcely possible for them to support life and reason under such a disgrace; and it appeared to her, that as far as this world alone was concerned, the greatest blessing to every one of kindred with Mrs. Rushworth would be instant annihilation.

Sweet creeping jebus.

We've come to expect morbidity from Fanny, but this really jumps the shark. The kind of mind that can't accommodate a family scandal without wishing for "instant annihilation" is of the febrile, unhealthy kind that is about the last thing I'd associate with an Austen heroine. And of course the risky thing about leaping immediately to the extremity of hyperbole when things go bad, is that it leaves you nothing to reach for when things get worse. Which they now do.

Another letter arrives. (Don't worry, it's the last. I wish we could have a celebratory bonfire of all the missives Fanny has received over the past few chapters, but if the blaze got out of hand it would wipe out half of Portsmouth.) It's from Edmund, confirming that Maria and Henry have indeed run off to nobody-yet-knows-where, and adding: "You may not have heard of the last blow—Julia's elopement; she is gone to Scotland with Yates. She left London a few hours before we entered it. At any other time, this would have been felt dreadfully. Now it seems nothing, yet it is an heavy aggravation." Poor Julia, always second best, even as a black sheep.

And then—the silver lining to this double-dose of awful: Fanny is summoned home. Even better, Edmund is coming personally to fetch her. And—even more extra-super-duper—Susan is invited as well. (I guess the Bertrams figure, they're two females down, better re-stock.) Fanny is now genuinely torn, between the nihilist attractions of wishing her nearest and dearest all wiped from the face of the Earth, and the giddy excitement of knowing she is at long last escaping the grease pit she grew up in. She has to keep reminding herself that life as she knew it is now over and all who love her are forever doomed, even as she packs up her luggage with squeals of delight. Susan feels this conflict as well, though less strongly because she doesn't personally know the disgraced principals; "if she could help rejoicing from beginning to end, it was as much as ought to be expected from human virtue at fourteen."

Then the happy day arrives, and Edmund with it; and if you thought Fanny was melodramatic, get a load of this guy. He appears at the house with suffering etched into his face, and presses Fanny to his breast with the words, "My Fanny—my only sister—my only comfort now." All right, fine, it's a tad purple but arguably excusable under the circumstances; what's not excusable is that he appears to pay no compliments of any kind to the Prices. It's as though the Enormity Of His Suffering places him on a higher plane where he isn't required to engage in such bothersome niceties as Hello you must be my Aunt Price, what a pleasure to know you, and could this little pumpkin be my cousin Betsey? No, no, slumming with the Prices is good enough for a slick charmer like Henry Crawford, but not for the lofty Edmund Bertram. When he finds to his annoyance that Fanny and Susan haven't breakfasted yet, he goes off by himself till they're ready, "glad to get away even from Fanny," and spends an hour walking the ramparts, looking soulfully tormented and romantically windblown in case anyone is secretly filming him.

He returns in time to "spend a few minutes with the family, and be a witness—but that he saw nothing—of the tranquil manner in which the daughters were parted with." Then they pile into the carriage and set off. The journey is, as you can imagine, a silent one.

Edmund's deep sighs often reached Fanny. Had he been alone with her, his heart might have opened in spite of every resolution; but Susan's presence drove him quite into himself, and his attempts to talk on indifferent subjects could never be long supported.

Eventually Edmund takes actual notice of Fanny—probably when he's grown bored of staring at the scenery, or his navel—and notices how haggard she is. Having been completely in a fog during his seventy-three seconds in the Price household, he has no idea that the stress of living in such a pressure-cooker has contributed to her withered looks, and he presumes, with all the egocentric arrogance of those who account theirs the only significant suffering in all of human history, that she's just feeling a reflection of his own titanic torment:

…(He) took her hand, and said in a low, but very expressive tone, "No wonder—you must feel it—you must suffer. How a man who had once loved, could desert you! But your's—your regard was new compared with—Fanny, think of me!"

I have a standard response for people who give me this "How do you think I feel?" line. I say, "I don't have to think. You always tell me." (I wish I could report that this actually shuts them up. But anyone that self-involved is usually completely immune to subtlety.)

When they reach the environs of Mansfield, Fanny can't help her spirits rising; here again are all those hedges she so much likes to heap with hosannas. And in fact she goes on for a paragraph delightedly noting all the changes in color and volume and clapping her hands and whistling and barking out the window. Unfortunately her two companions can't share in her enjoyment; Susan is suddenly fretting about how she'll manage to keep from betraying her vulgarity, and "was meditating much on silver forks, napkins, and finger glasses," while Edmund is still sunk into profound contemplation on the tragedy of being Edmund, "with eyes closed as if the view of cheerfulness oppressed him"; oh yeah, Edmund the contented clergyman is bit of a dullard, but Edmund the self-pitying martyr could bore the paint right off the walls.

Everyone is utterly morose, and we know that once we get to Mansfield neither Sir Thomas, Lady Bertram, or Tom will be any livelier, so our only hope of relief is in Aunt Norris. But once we arrive at the house and the cast is reassembled, we can see that in many ways she's the worst off of the bunch. Maria was her particular favorite, and the match with Mr. Rushworth was one she personally arranged for her, so Maria's disgrace is her own, and she's feeling it big time. Her "active powers had been all benumbed" and she found herself "unable to direct or dictate, or even fancy herself useful." The only spark of the old Aunt Norris is the extreme vexation she feels at "the sight of the person whom, in the blindness of her anger, she could have charged as the demon of the piece. Had Fanny accepted Mr. Crawford, this could not have happened." She also works up "a few repulsive looks" for Susan, and we have hopes for more, but alas, nothing comes of it.

As for the other aunt in the house, "(t)o talk over the dreadful business with Fanny, talk and lament, was all Lady Bertram's consolation." And while she is "no very methodical narrator," it's through her that Fanny begins to piece together what exactly the hell has happened, anyway.

It seems Mr. Rushworth had gone to Twickehnham for the Eastter holidays, leaving Maria with a family of "lively, agreeable manners, and probably of morals and discretion to suit"—you know, urbanities—and "to their house Mr. Crawford had constant access at all times." Julia wasn't around to provide even the featherweight of balance she might have offered, because she'd gone off to be somebody else's houseguest. Frolics and romps apparently ensued, because eventually a friend of Sir Thomas's wrote to urge him to come to town and use "influence with his daughter, to put an end to an intimacy which was already exposing her to unpleasant remarks," without providing exactly what the unpleasant remarks were, which seems unfair to those of us who would really, really like to know.

Before Sir Thomas can load his valise onto the carriage, however, another letter arrives from the same friend—express, so you know it's some baaad nastiness—with the news that Maria has absconded with Mr. Crawford. Sir Thomas lights out for London and hunkers down, no doubt ducking his head beneath the volleys of pernicious gossip flying across town (principally lobbed by Maria's mother-in-law's servant, who really seems to deserve a spin-off of her own), and persists "in the hope of discovering, and snatching her from farther vice, though all was lost on the side of character." Hey, we're talking about Maria, here. All was lost on the side of character before she had permanent teeth.

And then, and only then, does he learn Julia has eloped with Mr. Yates.

Fanny can't but pity poor Sir Thomas, with three children now burdening him with worry (since Tom has had a setback on hearing all the bad news). He also has to endure pity for his youngest son (who would insist on being pitied, if there were any doubt) in having been so brutally disappointed by the woman of his dreams, who it now seems will never be the wee little wifey of his country parsonage.

Because it turns out the final meeting between Edmund and Mary Crawford was about as final as it could possibly be, barring one of them actually shooting the other dead. He divulges to Fanny that he had gone to see her at Lady Stornaway's house, eager to commiserate with her and "investing her with all the feelings of shame and wretchedness which Crawford's sister ought to have known," only to have her bring up the subject in a breezy, mock-exasperated manner: "Let us talk over this sad business," she says. "What can equal the folly of our two relations?" When Edmund's face registers unmistakable shock—possibly his jaw drops sixteen inches and his eyeballs sproing out of his head like in a Tex Avery cartoon—she backpedals, noting gravely, 'I do not mean to defend Henry at your sister's expence."

"So she began—but how she went on, Fanny, is not fit—is hardly to be repeated to you. I cannot recall all her words. I would not dwell upon them if I could. Their substance was great anger at the folly of each…Guess what I must have felt. To hear the woman whom—no harsher name than folly given!—So voluntarily, so freely, so coolly to canvass it!—No reluctance, no horror, no feminine—shall I say it? no modest loathings!—This is what the world does."

By which he means, "This is what the city does."

I'm not sure what Edmund wants here. Mary is putting the best face possible on things; she's stiffening her spine and striving to keep a cool head, and to patch up the mess as tidily as possible (she wants Edmund's aid in forcing Henry and Maria to marry). Her manner is practical, rational, unsentimental…English. Whereas Henry seems to want her to fall shrieking to the carpet, at which the two of them can wail and flail and pull their hair out at the roots like hysterical continentals.

Mary goes on to shock Edmund further, by laying some of the blame at Fanny's door.

"Why, would not she have him? It is all her fault. Simple girl!—I shall never forgive her. Had she accepted him as she ought, they might now have been on the point of marriage, and Henry would have been too happy and too busy to want any other object. He would have taken no pains to be on terms with Mrs. Rushworth again. It would have all ended in a regular standing flirtation, in yearly meetings at Southerton and Everingham."

This kind of sophistication just about gives Edmund renal failure. Never mind that she's absolutely right. Maybe that even makes it worse. But to us, the lightness with which Mary attempts to deal with the scandal is entirely natural; she's 250 years ahead of her time. (I've said it before, but it bears repeating: she's a Noël Coward heroine in a Jane Austen novel.) To our eyes, the great affronted show Edmund makes of being shocked, shocked by everything she says, comes across as stuffy and excessive. "I do not consider her as meaning to wound my feelings," he says. "The evil lies yet deeper; in her total ignorance, unsuspiciousness of there being such feelings, in a perversion of mind which made it natural to her to treat the subject as she did." To treat it, he means, as a problem to be solved rather than the fall of western civilization. "Her's are faults of principle, Fanny, of blunted delicacy and a corrupted, vitiated mind…Gladly would I submit to all the increased pain of losing her, rather than have to think of her as I do. I told her so." Yeah, I just bet you did.

Mary's idea is that, once married to Henry, "and properly supported by her own family, people of respectability as they are, (Maria) may recover her footing in society to a certain degree."

"In some circles, we know, she would never be admitted, but with good dinners, and large parties, there will always be those who will be glad of her acquaintance; and there is, undoubtedly, more liberality and candour on those points than formerly. What I advise is, that your father be quiet. Do not let him injure his own cause by interference…Let Sir Thomas trust to his honour and compassion, and it may all end well; but if he get his daughter away, if will be destroying the chief hold."

Honor and compassion…forgiveness and a chance at redemption…we're meant to find this despicable? Edmund says, emphatically, yes. In his view, Mary proposes nothing less than "a compromise, an acquiescence, in the continuance of the sin, on the chance of a marriage which, thinking as I now thought of her brother, should rather be prevented than sought"—and at about this moment you might want to stop and say, Fine, buddy, what's your suggested plan for the lovers, then? Because it seems to be something along the lines of stoning them to death, then driving stakes through their hearts and stuffing their mouths with garlic.

Edmund delivers a thundering denunciation that leaves Mary "exceedingly astonished—more than astonished" and reduces to sarcasm as he walks out on her; which we of course recognize as the last angry recourse of wounded pride.

"It was a sort of laugh, as she answered, 'A pretty good lecture, upon my word. Was it part of your last sermon? At this rate, you will soon reform every body at Mansfield and Thornton Lacey; and when I hear of you it may be as a celebrated preacher in some great society of Methodists, or as a missionary into foreign parts.' She tried to speak carelessly; but she was not so careless as she wanted to appear."

As Edmund heads out the door, she calls out to him; he turns around and she smiles—a "saucy playful smile"—and he keeps on going.

All right, let's not dwell on it. This is the nadir; the place Jane Austen really jumps the rails and sends the whole train careening into the jagged canyon below. But it's the only time in her entire body of work she does so—and that includes her juvenilia and unfinished novels—so we can forgive her this momentary dementia.

Mention of the juvenilia prompts an interesting thought, which is that Mansfield Park represents a more or less thorough betrayal of the young writer who produced all those wacky, anarchic, calamity-choked mini-masterpieces; her spirit of wild invention, cheeky wit and subversive hooliganism is the kind that's actively punished in the present novel. Maybe Austen exorcised her Puritan demons in the process; if so, we can only be thankful. Anyway, onward.

Now that Edmund has confessed his newfound horror of the woman he once loved, Fanny feels "at liberty to speak" and "more than justified in adding to his knowledge of her real character, by some hint of what share his brother's state of health might be supposed to have in her wish for a complete reconciliation." In other words, it's pile-on-Mary time. And it ain't pretty, believe me.

Then Austen clears the slate, proclaiming "Let other pens dwell on guilt and misery. I quit such odious subjects as soon as I can, impatient to restore every body, not greatly in fault themselves, to tolerable comfort, and to have done with all the rest." By this time we're ready to rassle her some over her definition of "greatly at fault," but it's the last bloody chapter, so we let it go in the interest of just finishing the thing.

"My Fanny," she goes on (and yes, thanks, you can have her), "I have the satisfaction of knowing, must have been happy in spite of every thing," and here she enumerates every reason in favor of that happiness, though if anyone could sniff out a square inch of misery in an acre of paradise, it's Fanny. And given that Austen repeatedly uses the conditional tense (she "must have been" happy), I'm guessing even she isn't a hundred percent convinced of it.

But if Fanny is happy, those around her certainly aren't; Edmund has taken his consumptive-Lord-Byron act to heights undreamed of in Portsmouth, and Sir Thomas is mired in regret and self-reproach for having raised up under his own roof a pair of man-devouring succubi. But news eventually arrives that somewhat redeems Julia; it seems her elopement with Mr. Yates was prompted less by selfish lust than by a strong streak of self-preservation. After Maria ran off with Henry Crawford, she realized her family's reputation was about to seriously tank, so she'd better grab whatever suitor was closest at hand and marry him now, or she'd end up on the shelf for the rest of her life. Mr. Yates just happened to be the man within reach. Sir Thomas eventually reconciles with his daughter, who is "humble and wishing to be forgiven," and reconciles himself to his new son-in-law, who while "not very solid" is at least earnest and willing to be guided.

And then Tom's health improves, which further lessens the weight of Sir Thomas's woes, and indeed Tom is so chastened by his cha-cha-cha with death, and by his culpability in l'affaire Crawford ("he felt himself accessory by all the dangerous intimacy of his unjustifiable theatre") that he becomes "what he ought to be, useful to his father, steady and quiet, and not living merely for himself." Well, fine. Everyone has to grow up. Just tell me he could still crack his tongue like a whip, and that his dinner guests were always left gasping for breath by the cheese course.

Maria, however, remains intractable; Sir Thomas won't ever find a lessening of torment on her account.

She was not to be prevailed on to leave Mr. Crawford. She hoped to marry him, and they continued together till she was obliged to be convinced that such hope was vain, and till the disappointment and wretchedness arising from the conviction, rendered her temper so bad, and her feelings for him so like hatred, as to make them for a while each other's punishment, and then induce a voluntary separation.

She had lived with him to be reproached as the ruin of all his happiness in Fanny, and carried away no better consolation in leaving him, than that she had divided them. What can exceed the misery of such a mind in such a situation?

I'm pretty sure Maria's misery is exceeded when she learns that Fanny has married her brother on the rebound. But alas, Austen doesn't confirm this.

Mr. Rushworth has no trouble getting a quickie divorce, and Austen cautions us not to pity him: his wife "had despised him, and loved another—and he had been very much aware that it was so. The indignities of stupidity, and the disappointments of selfish passion, can excite little pity." This is harsh. Austen really is in Savonarola mode in this novel. Unfortunately, she was insufficiently able to restrict her own gifts, as to prevent herself from giving us that one moment in which Rushworth showed us his humanity—displayed a flicker of self-awareness and of suffering at Maria's open favoring of Crawford over him—so that I haven't been able to laugh at him as easily since, or to dismiss him so callously now. With a flick of her wrist she dressed him in flesh and blood, and I'm not entirely sure she even knew she did it.

The problem is, then, what to do with Maria. Aunt Norris, "whose attachment seemed to augment with the demerits of her niece," wants her to be received back home and resume her place as queen bitch of Mansfield, but Sir Thomas is basically over-my-dead-body. Which makes Aunt Norris glare daggers at Fanny, flitting around the very house Maria is now denied, and you can tell she wants to ask, What about her dead body, but doesn't dare to.

No, Sir Thomas has a pretty clear idea of what to do with Maria, which is basically, lock her up somewhere far away, protected by him and "secured in every comfort," but basically under house arrest. If the technology existed, he'd put her in an ankle monitor. And as a companion, she'll have Mrs. Norris, which is a bit of an eyebrow-raiser, because so far from being a chaperon, Aunt Norris has proven herself many times over to be Maria's biggest cheerleading enabler in every self-destructive thing she's ever done. But "shut up together, with little society, on one side no affection, on the other, no judgment, it may be reasonably supposed that their tempers became their mutual punishment."

And Sir Thomas is more than ready to boot Aunt Norris's knobby white ass out the door anyway.

His opinion of her had been sinking from the day of his return from Antigua; in every transaction together from that period, in their daily intercourse, in business, or in chat, she had been regularly losing ground in his esteem…To be relieved from her, therefore, was so great a felicity, that had she not left bitter remembrances behind her, there might have been danger of his learning almost to approve the evil which produced such a good.

And what of Henry Crawford?...He has to live with his very real regrets of Fanny. Had he only been able to win her, "there would have been every probability of success and felicity for him. His affection had already done something. Her influence over him had already given him some influence over her." In a number of places Austen confirms, or at least hints, that both Henry and Mary would have been reformed by unions with Fanny and Edmund. That we've had to witness two charming favorites shunted so brusquely aside, redemption denied them, is a pretty rum business. What is Henry Crawford's real sin, anyway?...Being human; being complex; being young.

…(B)y animated perseverance he had soon re-established the sort of familiar intercourse—of gallantry—of flirtation (with Maria) which bounded his views, but in triumphing over the discretion, which, though beginning in anger, might have saved them both, he had put himself in the power of feelings on her side, more strong than he had supposed.—She loved him; there was no withdrawing attentions, avowedly dear to her. He was entangled by his own vanity, with as little excuse of love as possible, and without the smallest inconstancy of mind towards her cousin.

This is not a cad. Austen seems to be using him as the protagonist in a cautionary tale, dooming him to "vexation that must rise sometimes to self-reproach, and regret to wretchedness—in having so requited hospitality, so injured family peace, so forfeited his best, most estimable, and endeared acquaintance, and so lost the woman whom he had rationally, as well as passionately, loved." No starched-collared Victorian could have sentenced him with more scowling prejudice.

Mary too must go on blithely twittering through life, regretting of, and pining for, Edmund; and the Grants—remember them?—have to be hustled offstage (to a new living for the rector) because their continued presence in Mansfield is now too awkward to be convenient to the story. There's a whole lot of suffering going on here and if these are the peeps Austen considers "greatly at fault" then you have to wonder what happened to her. I mean, this is the woman who basically let Lydia Bennet and George Wickham get away with metaphorical murder. And Lucy Steele and Robert Ferrars, too. Part of Austen's appeal to me has always been her serene indifference to the success of her grinning predators. As long as her heroine (and hero) ended up happy, she seemed content to leave everyone else alone—on the principle, I suppose, that the worst imaginable punishment would be allowing them to continue being themselves. (Certainly true of Lydia and Wickham.) Here, she's chosen instead to channel some Old Testament prophet, and smite the sinners with an iron fist.

I don't want cautionary tales from Austen; if she reforms the human race at all, it will be through relentless mockery of its pretensions, hypocrisies, and delusions, not through moral fables about virtues ingenues. She's strayed from her true path here, and we're left following her, stepping entirely too trustingly into stinging nettles and poison oak.

In one respect, however, she happily hasn't changed; she remains as indifferent as ever to what we moderns understand as "romance." The passage in which Edmund turns his mind from Mary to Fanny is almost plangently matter-of-fact, with him wondering whether, it being "impossible that he should ever meet with another such woman…a very different type of woman might do just as well—or a great deal better." He might be contemplating a change from planting radishes to beets. And then there's this:

I purposely abstain from dates on this occasion, that every one may be at liberty to fix their own, aware that the cure of unconquerable passions, and the transfer of unchanging attachments, must vary much as to time in different people.—I only intreat every body to believe that exactly at the time when it was quite natural that it should be so, and not a week earlier, Edmund did cease to care about Miss Crawford, and became as anxious to marry Fanny, as Fanny herself could desire.

You feel the earth move?...Me neither.

The novel ends on several pages of self-congratulation, but it tastes a bit stale on the tongue. Especially since our author has admitted that both Henry and Mary Crawford would have benefited from their respective matches with Fanny and Edmund; their appetites curbed, their excesses restrained, their characters inclined more to responsibility. And Fanny and Edmund would have had to learn to accommodate, forgive, and even appreciate human fallibility; to love someone else for his or her faults, not in spite of them. All that is sundered on a single youthful folly; and Mary's practical approach to limiting the damage is viewed as evidence of a damaged character—while Edmund's refusal to do anything but wallow in the wretchedness of it all, like an especially highly strung Italian peasant, is apparently the height of moral perfection. I just don't get this. I don't get why we're meant to celebrate four people missing out on the unions that would have redefined and improved them; why we're meant instead to go all gooey over Edmund finding perfect peace and contentment with Fanny, who's been his lap dog since they were juveniles—a marriage that promises no friction, no compromises, no self-sacrifice, no soul-searching…it's static; a placid pool, with nothing to disturb its smooth surface except, inevitably, the swift spread of algae. Mary and Henry are left unmoored and heartbroken…Edmund and Fanny are left retreating into the womb of their childhood…what? I'm supposed to rejoice?

Another point I must at least touch on: I've noted repeatedly how immune I remain to the Fanny-Edmund pairing. There's never, for me, even the slightest evidence of the kind of chemistry we saw between Lizzy and Darcy, or even Elinor and Edward Ferrars. I'm at least willing to admit that part of the reason—albeit a small part—is a cultural resistance to the idea of first cousins as lovers. I know things were different back in Austen's era; in a smaller population with clearly defined class boundaries, the dating pool was naturally more limited than it is for us today. But the distaste for such a pairing in our own culture isn't something we can easily set aside, and I find myself reading of Fanny and Edmund's coming together with a grimace of sexual distaste on my face that I can't seem to wipe away. Couple that with the whole undercurrent of the Antiguan slave trade, and you've got a novel with some serious handicaps all the way through. Clone a dozen Aunt Norrises and set them running through its pages like a herd of wildebeest, and you still couldn't fix it.

But the primary and ultimately decisive problem is still the empty dress at the center of it all. When she began her next novel, Austen wrote to her sister, "I am going to take a heroine whom no one but myself will much like." But she was wrong; Emma Woodhouse is almost universally adored. It's Fanny Price who has borne the brunt of readers' dislike and disdain over the centuries. Inert, joyless, and judgmental, she stands to one side for the entirety of Mansfield Park while its other characters strive, battle, and fall, and in the end her strategy of doing nothing wins her everything she's ever wanted. Fanny, who never takes a risk, never tells a joke, is never silly or unwise or exultant or—frankly—human, triumphs over her enemies and her rivals by virtue of her sheer indomitable passivity.

And what of those enemies and rivals? They aren't as quite numerous as in Austen's previous works, though quality nearly makes up for scarcity. There's the fatuous Mr. Rushworth; battering Aunt Norris; gabbling Mr. Yates; and the wonderfully hyena-like Price clan. But then, alas, we come to the main focuses of our intended ire: Mary Crawford and her brother Henry. They're witty, charming, incautious, unthinking…emotional and headlong and sensual and indiscreet. To our modern sensibilities, they're romantic heroes, complete with tragic flaws. Edmund, our nominal hero, is a good man, true, but he's parched soil, gasping for want of laughter and energy and magic; for the blessing of uncertainty; for life. Instead he winds up with Fanny; their union is a guarantee of spiritual and emotional barrenness. In so frictionless a pairing, nothing can alter, nothing ever change, nothing ever grow.

I've conjectured long and hard about why Austen wrote Mansfield Park; but whatever the reason, the good news is, she learned from the endeavor…and she shows as much in her next novel, which is basically Mansfield Park turned on its head. Its heroine, Emma Woodhouse, is a revisited Mary Crawford—a sly, feline charmer who's quick to judgment and carelessly glib, and is made to pay for it; but this time, crucially, she's forgiven. Her rival, Jane Fairfax, is a new incarnation of Fanny Price—chilly, impenetrable, aloof; and like Fanny, her imperturbable stillness wins her her man in the end. But in this case it's exactly the right man for her: Frank Churchill, whose wily roguishness will force her to enlarge her own capacity for understanding; as her quiet determination will galvanize his. Because of this ingenious inversion, Emma scintillates where Mansfield Park stalls out; Emma delights where Mansfield Park frustrates; and Emma is beloved, where Mansfield Park, despite its many brilliant facets and enduring moments, seems fated to remain only tolerated.

But no; the letter is instead a strange, cryptic thing, urging Fanny to ignore a "most scandalous, ill-natured rumour" that's just come to Mary's ear, and assuring her that "Henry is blameless, and in spite of a moment's etouderie thinks of nobody but you."

I am sure it will all be hushed up, and nothing proved but Rushworth's folly. If they are gone, I would lay my life they are only gone to Mansfield Park, and Julia with them. But why would not you let us come for you? I wish you may not repent it.

Fanny is mystified. No scandalous, ill-natured rumour has reached her; in her little Portsmouth cocoon, it's a miracle if oxygen reaches her. "She could only perceive that it must relate to Wimpole Street and Mr. Crawford, and only conjecture that something very imprudent had just occurred in that quarter to draw the notice of the world," though why she should care whether the Rushworths then beat a hasty retreat, and where they went, and whether Julia was with them, is beyond her.

As to Mr. Crawford, she hoped it might give him a knowledge of his own disposition, convince him that he was not capable of being steadily attached to any one woman in the world, and shame him from persisting any longer in addressing herself.

Yes, that would be best. Leave Fanny to her little airless existence where the taint of inconvenient human feeling needn't disturb her inertia. Think I'm being too harsh?...Here's Fanny's own POV on the situation.

She felt that she had, indeed, been three months (in Portsmouth); and the sun's rays falling into the parlour, instead of cheering, made her still more melancholy; for sun-shine appeared to her a totally different thing in a town and in the country. Here, its power was only a glare, a stifling, sickly glare, serving to bring forward stains and dirt that might otherwise have slept. There was neither health nor gaiety in sunshine in a town. She sat in a blaze of oppressive heat, in a cloud of moving dust; and her eyes could only wander from the walls marked by her father's head, to the table cut and knotched by her brothers, where stood the tea-board never thoroughly cleaned, the cups and saucers wiped in streaks, the milk a mixture of motes floating in thin blue, and the bread and butter growing every minute more greasy than even Rebecca's hands had first produced it.

Killer bit of writing there, btw.

It's in this scene of domestic oblivion that the scandalous, ill-natured rumour finally reaches Fanny's ear, by the unlikeliest source imaginable: her boozy old man and his borrowed broadsheet. He looks up from its pages and says, "What's the name of your great cousins in town, Fan?" and when she answers Rushworth, and confirms they live on Wimpole Street, he's tickled pink.

"Then, there's the devil to pay among them, that's all. There, (holding out the paper to her)—much good may such fine relations do you. I don't know what Sir Thomas may think of such matters; he may be too much of the courtier and fine gentleman to like his daughter the less. But by G— if she belonged to me, I'd give her the rope's end as long as I could stand over her."

Which might not be too long, given that standing unassisted isn't exactly one of Mr. Price's superpowers. Still, the point is made: one of Sir Thomas's daughters has been extra-special naughty. Fanny takes up the paper and reads a report of "a matrimonial fracas in the family of Mr. R. of Wimpole Street," whose beautiful young bride (whose name "had not long been enrolled in the lists of hymen"—love that turn of phrase) has "quitted her husband's roof in the company of the well known and captivating Mr. C. …and it was not known, even to the editor of the newspaper, whither they were gone." Why the editor of the newspaper should be expected to know above anyone else, I'm not quite sure. Possibly he's a Regency Perry White or something.

Fanny insists that this is all a terrible mistake, even though she knows it's not. (Scarcely the first instance of Fanny deliberate obscuring the facts.) She speaks "from the instinctive wish of delaying shame," but she might have spared herself the trouble, because her father doesn't really give a good goddamn; now that he's scored a cheap point off her, he's fine just letting the whole thing drop. As for Fanny's mother, her reaction is hilariously typical.

"Indeed, I hope it is not true," said Mrs. Price plaintively; "it would be so very shocking!—If I have spoke once to Rebecca about that carpet, I am sure I have spoke at least a dozen times; have I not, Betsey?—And it would not be ten minutes work."

Fanny meanwhile retreats to do what Fanny does best, which is languish and brood. She torments herself by going over everything again and again and again, like someone stuck in a time loop, and coming to the same inevitable (and, I'm betting, secretly satisfying) conclusions, especially with regard to Mary Crawford.

Her eager defense of her brother, her hope of its being hushed up, her evident agitation, were all of a piece with something very bad; and if there was a woman of character in existence, who could treat as a trifle this sin of the first magnitude, who could try to gloss it over, and desire to have it unpunished, she could believe Miss Crawford to be the woman!

There's a lot of anguished reflection on how horrible, horrible, horrible it all is, to the point at which you begin to feel uncomfortable, like you're witnessing a sadomasochist wallowing in the sheer pleasure of acute agony. She spends an almost pornographic amount of time speculating on who will be most injured by the scandal, and decides Sir Thomas wins that particular prize, with Edmund the silver medalist, and in minutely considering their emotional devastation she works herself into a kind of melodramatic fit.

Sir Thomas's parental solicitude, and high sense of honour and decorum, Edmund's upright principles, unsuspicious temper, and genuine strength of feeling, made her think it scarcely possible for them to support life and reason under such a disgrace; and it appeared to her, that as far as this world alone was concerned, the greatest blessing to every one of kindred with Mrs. Rushworth would be instant annihilation.

Sweet creeping jebus.

We've come to expect morbidity from Fanny, but this really jumps the shark. The kind of mind that can't accommodate a family scandal without wishing for "instant annihilation" is of the febrile, unhealthy kind that is about the last thing I'd associate with an Austen heroine. And of course the risky thing about leaping immediately to the extremity of hyperbole when things go bad, is that it leaves you nothing to reach for when things get worse. Which they now do.

Another letter arrives. (Don't worry, it's the last. I wish we could have a celebratory bonfire of all the missives Fanny has received over the past few chapters, but if the blaze got out of hand it would wipe out half of Portsmouth.) It's from Edmund, confirming that Maria and Henry have indeed run off to nobody-yet-knows-where, and adding: "You may not have heard of the last blow—Julia's elopement; she is gone to Scotland with Yates. She left London a few hours before we entered it. At any other time, this would have been felt dreadfully. Now it seems nothing, yet it is an heavy aggravation." Poor Julia, always second best, even as a black sheep.

And then—the silver lining to this double-dose of awful: Fanny is summoned home. Even better, Edmund is coming personally to fetch her. And—even more extra-super-duper—Susan is invited as well. (I guess the Bertrams figure, they're two females down, better re-stock.) Fanny is now genuinely torn, between the nihilist attractions of wishing her nearest and dearest all wiped from the face of the Earth, and the giddy excitement of knowing she is at long last escaping the grease pit she grew up in. She has to keep reminding herself that life as she knew it is now over and all who love her are forever doomed, even as she packs up her luggage with squeals of delight. Susan feels this conflict as well, though less strongly because she doesn't personally know the disgraced principals; "if she could help rejoicing from beginning to end, it was as much as ought to be expected from human virtue at fourteen."

Then the happy day arrives, and Edmund with it; and if you thought Fanny was melodramatic, get a load of this guy. He appears at the house with suffering etched into his face, and presses Fanny to his breast with the words, "My Fanny—my only sister—my only comfort now." All right, fine, it's a tad purple but arguably excusable under the circumstances; what's not excusable is that he appears to pay no compliments of any kind to the Prices. It's as though the Enormity Of His Suffering places him on a higher plane where he isn't required to engage in such bothersome niceties as Hello you must be my Aunt Price, what a pleasure to know you, and could this little pumpkin be my cousin Betsey? No, no, slumming with the Prices is good enough for a slick charmer like Henry Crawford, but not for the lofty Edmund Bertram. When he finds to his annoyance that Fanny and Susan haven't breakfasted yet, he goes off by himself till they're ready, "glad to get away even from Fanny," and spends an hour walking the ramparts, looking soulfully tormented and romantically windblown in case anyone is secretly filming him.

He returns in time to "spend a few minutes with the family, and be a witness—but that he saw nothing—of the tranquil manner in which the daughters were parted with." Then they pile into the carriage and set off. The journey is, as you can imagine, a silent one.

Edmund's deep sighs often reached Fanny. Had he been alone with her, his heart might have opened in spite of every resolution; but Susan's presence drove him quite into himself, and his attempts to talk on indifferent subjects could never be long supported.

Eventually Edmund takes actual notice of Fanny—probably when he's grown bored of staring at the scenery, or his navel—and notices how haggard she is. Having been completely in a fog during his seventy-three seconds in the Price household, he has no idea that the stress of living in such a pressure-cooker has contributed to her withered looks, and he presumes, with all the egocentric arrogance of those who account theirs the only significant suffering in all of human history, that she's just feeling a reflection of his own titanic torment:

…(He) took her hand, and said in a low, but very expressive tone, "No wonder—you must feel it—you must suffer. How a man who had once loved, could desert you! But your's—your regard was new compared with—Fanny, think of me!"

I have a standard response for people who give me this "How do you think I feel?" line. I say, "I don't have to think. You always tell me." (I wish I could report that this actually shuts them up. But anyone that self-involved is usually completely immune to subtlety.)

When they reach the environs of Mansfield, Fanny can't help her spirits rising; here again are all those hedges she so much likes to heap with hosannas. And in fact she goes on for a paragraph delightedly noting all the changes in color and volume and clapping her hands and whistling and barking out the window. Unfortunately her two companions can't share in her enjoyment; Susan is suddenly fretting about how she'll manage to keep from betraying her vulgarity, and "was meditating much on silver forks, napkins, and finger glasses," while Edmund is still sunk into profound contemplation on the tragedy of being Edmund, "with eyes closed as if the view of cheerfulness oppressed him"; oh yeah, Edmund the contented clergyman is bit of a dullard, but Edmund the self-pitying martyr could bore the paint right off the walls.

Everyone is utterly morose, and we know that once we get to Mansfield neither Sir Thomas, Lady Bertram, or Tom will be any livelier, so our only hope of relief is in Aunt Norris. But once we arrive at the house and the cast is reassembled, we can see that in many ways she's the worst off of the bunch. Maria was her particular favorite, and the match with Mr. Rushworth was one she personally arranged for her, so Maria's disgrace is her own, and she's feeling it big time. Her "active powers had been all benumbed" and she found herself "unable to direct or dictate, or even fancy herself useful." The only spark of the old Aunt Norris is the extreme vexation she feels at "the sight of the person whom, in the blindness of her anger, she could have charged as the demon of the piece. Had Fanny accepted Mr. Crawford, this could not have happened." She also works up "a few repulsive looks" for Susan, and we have hopes for more, but alas, nothing comes of it.

As for the other aunt in the house, "(t)o talk over the dreadful business with Fanny, talk and lament, was all Lady Bertram's consolation." And while she is "no very methodical narrator," it's through her that Fanny begins to piece together what exactly the hell has happened, anyway.

It seems Mr. Rushworth had gone to Twickehnham for the Eastter holidays, leaving Maria with a family of "lively, agreeable manners, and probably of morals and discretion to suit"—you know, urbanities—and "to their house Mr. Crawford had constant access at all times." Julia wasn't around to provide even the featherweight of balance she might have offered, because she'd gone off to be somebody else's houseguest. Frolics and romps apparently ensued, because eventually a friend of Sir Thomas's wrote to urge him to come to town and use "influence with his daughter, to put an end to an intimacy which was already exposing her to unpleasant remarks," without providing exactly what the unpleasant remarks were, which seems unfair to those of us who would really, really like to know.

Before Sir Thomas can load his valise onto the carriage, however, another letter arrives from the same friend—express, so you know it's some baaad nastiness—with the news that Maria has absconded with Mr. Crawford. Sir Thomas lights out for London and hunkers down, no doubt ducking his head beneath the volleys of pernicious gossip flying across town (principally lobbed by Maria's mother-in-law's servant, who really seems to deserve a spin-off of her own), and persists "in the hope of discovering, and snatching her from farther vice, though all was lost on the side of character." Hey, we're talking about Maria, here. All was lost on the side of character before she had permanent teeth.

And then, and only then, does he learn Julia has eloped with Mr. Yates.

Fanny can't but pity poor Sir Thomas, with three children now burdening him with worry (since Tom has had a setback on hearing all the bad news). He also has to endure pity for his youngest son (who would insist on being pitied, if there were any doubt) in having been so brutally disappointed by the woman of his dreams, who it now seems will never be the wee little wifey of his country parsonage.

Because it turns out the final meeting between Edmund and Mary Crawford was about as final as it could possibly be, barring one of them actually shooting the other dead. He divulges to Fanny that he had gone to see her at Lady Stornaway's house, eager to commiserate with her and "investing her with all the feelings of shame and wretchedness which Crawford's sister ought to have known," only to have her bring up the subject in a breezy, mock-exasperated manner: "Let us talk over this sad business," she says. "What can equal the folly of our two relations?" When Edmund's face registers unmistakable shock—possibly his jaw drops sixteen inches and his eyeballs sproing out of his head like in a Tex Avery cartoon—she backpedals, noting gravely, 'I do not mean to defend Henry at your sister's expence."

"So she began—but how she went on, Fanny, is not fit—is hardly to be repeated to you. I cannot recall all her words. I would not dwell upon them if I could. Their substance was great anger at the folly of each…Guess what I must have felt. To hear the woman whom—no harsher name than folly given!—So voluntarily, so freely, so coolly to canvass it!—No reluctance, no horror, no feminine—shall I say it? no modest loathings!—This is what the world does."

By which he means, "This is what the city does."

I'm not sure what Edmund wants here. Mary is putting the best face possible on things; she's stiffening her spine and striving to keep a cool head, and to patch up the mess as tidily as possible (she wants Edmund's aid in forcing Henry and Maria to marry). Her manner is practical, rational, unsentimental…English. Whereas Henry seems to want her to fall shrieking to the carpet, at which the two of them can wail and flail and pull their hair out at the roots like hysterical continentals.

Mary goes on to shock Edmund further, by laying some of the blame at Fanny's door.

"Why, would not she have him? It is all her fault. Simple girl!—I shall never forgive her. Had she accepted him as she ought, they might now have been on the point of marriage, and Henry would have been too happy and too busy to want any other object. He would have taken no pains to be on terms with Mrs. Rushworth again. It would have all ended in a regular standing flirtation, in yearly meetings at Southerton and Everingham."

This kind of sophistication just about gives Edmund renal failure. Never mind that she's absolutely right. Maybe that even makes it worse. But to us, the lightness with which Mary attempts to deal with the scandal is entirely natural; she's 250 years ahead of her time. (I've said it before, but it bears repeating: she's a Noël Coward heroine in a Jane Austen novel.) To our eyes, the great affronted show Edmund makes of being shocked, shocked by everything she says, comes across as stuffy and excessive. "I do not consider her as meaning to wound my feelings," he says. "The evil lies yet deeper; in her total ignorance, unsuspiciousness of there being such feelings, in a perversion of mind which made it natural to her to treat the subject as she did." To treat it, he means, as a problem to be solved rather than the fall of western civilization. "Her's are faults of principle, Fanny, of blunted delicacy and a corrupted, vitiated mind…Gladly would I submit to all the increased pain of losing her, rather than have to think of her as I do. I told her so." Yeah, I just bet you did.

Mary's idea is that, once married to Henry, "and properly supported by her own family, people of respectability as they are, (Maria) may recover her footing in society to a certain degree."

"In some circles, we know, she would never be admitted, but with good dinners, and large parties, there will always be those who will be glad of her acquaintance; and there is, undoubtedly, more liberality and candour on those points than formerly. What I advise is, that your father be quiet. Do not let him injure his own cause by interference…Let Sir Thomas trust to his honour and compassion, and it may all end well; but if he get his daughter away, if will be destroying the chief hold."

Honor and compassion…forgiveness and a chance at redemption…we're meant to find this despicable? Edmund says, emphatically, yes. In his view, Mary proposes nothing less than "a compromise, an acquiescence, in the continuance of the sin, on the chance of a marriage which, thinking as I now thought of her brother, should rather be prevented than sought"—and at about this moment you might want to stop and say, Fine, buddy, what's your suggested plan for the lovers, then? Because it seems to be something along the lines of stoning them to death, then driving stakes through their hearts and stuffing their mouths with garlic.

Edmund delivers a thundering denunciation that leaves Mary "exceedingly astonished—more than astonished" and reduces to sarcasm as he walks out on her; which we of course recognize as the last angry recourse of wounded pride.

"It was a sort of laugh, as she answered, 'A pretty good lecture, upon my word. Was it part of your last sermon? At this rate, you will soon reform every body at Mansfield and Thornton Lacey; and when I hear of you it may be as a celebrated preacher in some great society of Methodists, or as a missionary into foreign parts.' She tried to speak carelessly; but she was not so careless as she wanted to appear."

As Edmund heads out the door, she calls out to him; he turns around and she smiles—a "saucy playful smile"—and he keeps on going.

All right, let's not dwell on it. This is the nadir; the place Jane Austen really jumps the rails and sends the whole train careening into the jagged canyon below. But it's the only time in her entire body of work she does so—and that includes her juvenilia and unfinished novels—so we can forgive her this momentary dementia.

Mention of the juvenilia prompts an interesting thought, which is that Mansfield Park represents a more or less thorough betrayal of the young writer who produced all those wacky, anarchic, calamity-choked mini-masterpieces; her spirit of wild invention, cheeky wit and subversive hooliganism is the kind that's actively punished in the present novel. Maybe Austen exorcised her Puritan demons in the process; if so, we can only be thankful. Anyway, onward.

Now that Edmund has confessed his newfound horror of the woman he once loved, Fanny feels "at liberty to speak" and "more than justified in adding to his knowledge of her real character, by some hint of what share his brother's state of health might be supposed to have in her wish for a complete reconciliation." In other words, it's pile-on-Mary time. And it ain't pretty, believe me.

Then Austen clears the slate, proclaiming "Let other pens dwell on guilt and misery. I quit such odious subjects as soon as I can, impatient to restore every body, not greatly in fault themselves, to tolerable comfort, and to have done with all the rest." By this time we're ready to rassle her some over her definition of "greatly at fault," but it's the last bloody chapter, so we let it go in the interest of just finishing the thing.

"My Fanny," she goes on (and yes, thanks, you can have her), "I have the satisfaction of knowing, must have been happy in spite of every thing," and here she enumerates every reason in favor of that happiness, though if anyone could sniff out a square inch of misery in an acre of paradise, it's Fanny. And given that Austen repeatedly uses the conditional tense (she "must have been" happy), I'm guessing even she isn't a hundred percent convinced of it.

But if Fanny is happy, those around her certainly aren't; Edmund has taken his consumptive-Lord-Byron act to heights undreamed of in Portsmouth, and Sir Thomas is mired in regret and self-reproach for having raised up under his own roof a pair of man-devouring succubi. But news eventually arrives that somewhat redeems Julia; it seems her elopement with Mr. Yates was prompted less by selfish lust than by a strong streak of self-preservation. After Maria ran off with Henry Crawford, she realized her family's reputation was about to seriously tank, so she'd better grab whatever suitor was closest at hand and marry him now, or she'd end up on the shelf for the rest of her life. Mr. Yates just happened to be the man within reach. Sir Thomas eventually reconciles with his daughter, who is "humble and wishing to be forgiven," and reconciles himself to his new son-in-law, who while "not very solid" is at least earnest and willing to be guided.

And then Tom's health improves, which further lessens the weight of Sir Thomas's woes, and indeed Tom is so chastened by his cha-cha-cha with death, and by his culpability in l'affaire Crawford ("he felt himself accessory by all the dangerous intimacy of his unjustifiable theatre") that he becomes "what he ought to be, useful to his father, steady and quiet, and not living merely for himself." Well, fine. Everyone has to grow up. Just tell me he could still crack his tongue like a whip, and that his dinner guests were always left gasping for breath by the cheese course.

Maria, however, remains intractable; Sir Thomas won't ever find a lessening of torment on her account.

She was not to be prevailed on to leave Mr. Crawford. She hoped to marry him, and they continued together till she was obliged to be convinced that such hope was vain, and till the disappointment and wretchedness arising from the conviction, rendered her temper so bad, and her feelings for him so like hatred, as to make them for a while each other's punishment, and then induce a voluntary separation.

She had lived with him to be reproached as the ruin of all his happiness in Fanny, and carried away no better consolation in leaving him, than that she had divided them. What can exceed the misery of such a mind in such a situation?

I'm pretty sure Maria's misery is exceeded when she learns that Fanny has married her brother on the rebound. But alas, Austen doesn't confirm this.

Mr. Rushworth has no trouble getting a quickie divorce, and Austen cautions us not to pity him: his wife "had despised him, and loved another—and he had been very much aware that it was so. The indignities of stupidity, and the disappointments of selfish passion, can excite little pity." This is harsh. Austen really is in Savonarola mode in this novel. Unfortunately, she was insufficiently able to restrict her own gifts, as to prevent herself from giving us that one moment in which Rushworth showed us his humanity—displayed a flicker of self-awareness and of suffering at Maria's open favoring of Crawford over him—so that I haven't been able to laugh at him as easily since, or to dismiss him so callously now. With a flick of her wrist she dressed him in flesh and blood, and I'm not entirely sure she even knew she did it.

The problem is, then, what to do with Maria. Aunt Norris, "whose attachment seemed to augment with the demerits of her niece," wants her to be received back home and resume her place as queen bitch of Mansfield, but Sir Thomas is basically over-my-dead-body. Which makes Aunt Norris glare daggers at Fanny, flitting around the very house Maria is now denied, and you can tell she wants to ask, What about her dead body, but doesn't dare to.

No, Sir Thomas has a pretty clear idea of what to do with Maria, which is basically, lock her up somewhere far away, protected by him and "secured in every comfort," but basically under house arrest. If the technology existed, he'd put her in an ankle monitor. And as a companion, she'll have Mrs. Norris, which is a bit of an eyebrow-raiser, because so far from being a chaperon, Aunt Norris has proven herself many times over to be Maria's biggest cheerleading enabler in every self-destructive thing she's ever done. But "shut up together, with little society, on one side no affection, on the other, no judgment, it may be reasonably supposed that their tempers became their mutual punishment."

And Sir Thomas is more than ready to boot Aunt Norris's knobby white ass out the door anyway.

His opinion of her had been sinking from the day of his return from Antigua; in every transaction together from that period, in their daily intercourse, in business, or in chat, she had been regularly losing ground in his esteem…To be relieved from her, therefore, was so great a felicity, that had she not left bitter remembrances behind her, there might have been danger of his learning almost to approve the evil which produced such a good.

And what of Henry Crawford?...He has to live with his very real regrets of Fanny. Had he only been able to win her, "there would have been every probability of success and felicity for him. His affection had already done something. Her influence over him had already given him some influence over her." In a number of places Austen confirms, or at least hints, that both Henry and Mary would have been reformed by unions with Fanny and Edmund. That we've had to witness two charming favorites shunted so brusquely aside, redemption denied them, is a pretty rum business. What is Henry Crawford's real sin, anyway?...Being human; being complex; being young.

…(B)y animated perseverance he had soon re-established the sort of familiar intercourse—of gallantry—of flirtation (with Maria) which bounded his views, but in triumphing over the discretion, which, though beginning in anger, might have saved them both, he had put himself in the power of feelings on her side, more strong than he had supposed.—She loved him; there was no withdrawing attentions, avowedly dear to her. He was entangled by his own vanity, with as little excuse of love as possible, and without the smallest inconstancy of mind towards her cousin.

This is not a cad. Austen seems to be using him as the protagonist in a cautionary tale, dooming him to "vexation that must rise sometimes to self-reproach, and regret to wretchedness—in having so requited hospitality, so injured family peace, so forfeited his best, most estimable, and endeared acquaintance, and so lost the woman whom he had rationally, as well as passionately, loved." No starched-collared Victorian could have sentenced him with more scowling prejudice.

Mary too must go on blithely twittering through life, regretting of, and pining for, Edmund; and the Grants—remember them?—have to be hustled offstage (to a new living for the rector) because their continued presence in Mansfield is now too awkward to be convenient to the story. There's a whole lot of suffering going on here and if these are the peeps Austen considers "greatly at fault" then you have to wonder what happened to her. I mean, this is the woman who basically let Lydia Bennet and George Wickham get away with metaphorical murder. And Lucy Steele and Robert Ferrars, too. Part of Austen's appeal to me has always been her serene indifference to the success of her grinning predators. As long as her heroine (and hero) ended up happy, she seemed content to leave everyone else alone—on the principle, I suppose, that the worst imaginable punishment would be allowing them to continue being themselves. (Certainly true of Lydia and Wickham.) Here, she's chosen instead to channel some Old Testament prophet, and smite the sinners with an iron fist.

I don't want cautionary tales from Austen; if she reforms the human race at all, it will be through relentless mockery of its pretensions, hypocrisies, and delusions, not through moral fables about virtues ingenues. She's strayed from her true path here, and we're left following her, stepping entirely too trustingly into stinging nettles and poison oak.

In one respect, however, she happily hasn't changed; she remains as indifferent as ever to what we moderns understand as "romance." The passage in which Edmund turns his mind from Mary to Fanny is almost plangently matter-of-fact, with him wondering whether, it being "impossible that he should ever meet with another such woman…a very different type of woman might do just as well—or a great deal better." He might be contemplating a change from planting radishes to beets. And then there's this:

I purposely abstain from dates on this occasion, that every one may be at liberty to fix their own, aware that the cure of unconquerable passions, and the transfer of unchanging attachments, must vary much as to time in different people.—I only intreat every body to believe that exactly at the time when it was quite natural that it should be so, and not a week earlier, Edmund did cease to care about Miss Crawford, and became as anxious to marry Fanny, as Fanny herself could desire.

You feel the earth move?...Me neither.

The novel ends on several pages of self-congratulation, but it tastes a bit stale on the tongue. Especially since our author has admitted that both Henry and Mary Crawford would have benefited from their respective matches with Fanny and Edmund; their appetites curbed, their excesses restrained, their characters inclined more to responsibility. And Fanny and Edmund would have had to learn to accommodate, forgive, and even appreciate human fallibility; to love someone else for his or her faults, not in spite of them. All that is sundered on a single youthful folly; and Mary's practical approach to limiting the damage is viewed as evidence of a damaged character—while Edmund's refusal to do anything but wallow in the wretchedness of it all, like an especially highly strung Italian peasant, is apparently the height of moral perfection. I just don't get this. I don't get why we're meant to celebrate four people missing out on the unions that would have redefined and improved them; why we're meant instead to go all gooey over Edmund finding perfect peace and contentment with Fanny, who's been his lap dog since they were juveniles—a marriage that promises no friction, no compromises, no self-sacrifice, no soul-searching…it's static; a placid pool, with nothing to disturb its smooth surface except, inevitably, the swift spread of algae. Mary and Henry are left unmoored and heartbroken…Edmund and Fanny are left retreating into the womb of their childhood…what? I'm supposed to rejoice?

Another point I must at least touch on: I've noted repeatedly how immune I remain to the Fanny-Edmund pairing. There's never, for me, even the slightest evidence of the kind of chemistry we saw between Lizzy and Darcy, or even Elinor and Edward Ferrars. I'm at least willing to admit that part of the reason—albeit a small part—is a cultural resistance to the idea of first cousins as lovers. I know things were different back in Austen's era; in a smaller population with clearly defined class boundaries, the dating pool was naturally more limited than it is for us today. But the distaste for such a pairing in our own culture isn't something we can easily set aside, and I find myself reading of Fanny and Edmund's coming together with a grimace of sexual distaste on my face that I can't seem to wipe away. Couple that with the whole undercurrent of the Antiguan slave trade, and you've got a novel with some serious handicaps all the way through. Clone a dozen Aunt Norrises and set them running through its pages like a herd of wildebeest, and you still couldn't fix it.

But the primary and ultimately decisive problem is still the empty dress at the center of it all. When she began her next novel, Austen wrote to her sister, "I am going to take a heroine whom no one but myself will much like." But she was wrong; Emma Woodhouse is almost universally adored. It's Fanny Price who has borne the brunt of readers' dislike and disdain over the centuries. Inert, joyless, and judgmental, she stands to one side for the entirety of Mansfield Park while its other characters strive, battle, and fall, and in the end her strategy of doing nothing wins her everything she's ever wanted. Fanny, who never takes a risk, never tells a joke, is never silly or unwise or exultant or—frankly—human, triumphs over her enemies and her rivals by virtue of her sheer indomitable passivity.

And what of those enemies and rivals? They aren't as quite numerous as in Austen's previous works, though quality nearly makes up for scarcity. There's the fatuous Mr. Rushworth; battering Aunt Norris; gabbling Mr. Yates; and the wonderfully hyena-like Price clan. But then, alas, we come to the main focuses of our intended ire: Mary Crawford and her brother Henry. They're witty, charming, incautious, unthinking…emotional and headlong and sensual and indiscreet. To our modern sensibilities, they're romantic heroes, complete with tragic flaws. Edmund, our nominal hero, is a good man, true, but he's parched soil, gasping for want of laughter and energy and magic; for the blessing of uncertainty; for life. Instead he winds up with Fanny; their union is a guarantee of spiritual and emotional barrenness. In so frictionless a pairing, nothing can alter, nothing ever change, nothing ever grow.

I've conjectured long and hard about why Austen wrote Mansfield Park; but whatever the reason, the good news is, she learned from the endeavor…and she shows as much in her next novel, which is basically Mansfield Park turned on its head. Its heroine, Emma Woodhouse, is a revisited Mary Crawford—a sly, feline charmer who's quick to judgment and carelessly glib, and is made to pay for it; but this time, crucially, she's forgiven. Her rival, Jane Fairfax, is a new incarnation of Fanny Price—chilly, impenetrable, aloof; and like Fanny, her imperturbable stillness wins her her man in the end. But in this case it's exactly the right man for her: Frank Churchill, whose wily roguishness will force her to enlarge her own capacity for understanding; as her quiet determination will galvanize his. Because of this ingenious inversion, Emma scintillates where Mansfield Park stalls out; Emma delights where Mansfield Park frustrates; and Emma is beloved, where Mansfield Park, despite its many brilliant facets and enduring moments, seems fated to remain only tolerated.

Published on October 27, 2011 14:38

October 16, 2011

Mansfield Park, chapters 43-45

Fanny Price, the supposed heroine of Mansfield Park, has spent pretty much the entirety of the novel standing off on the margins while the other characters provide all the plot action. Occasionally she's got in their way or underfoot, and they've had to talk over or around her, or to each other through her, but now that she's been removed to Portsmouth her essential irrelevance becomes harder to disguise. For the next several chapters, Fanny's role is reduced to no more than reading letters from (and about) home. In essence, she's fallen out of the novel and become one of us; Jane Austen, that Regency postmodernist, has gone meta. We read Mansfield Park, in which Fanny Price reads about Mansfield Park. Her text is our text; we peer at it over her shoulder.