Peter Michaelson's Blog, page 11

August 21, 2018

Why We Urgently Need Inner Truth

Is there perhaps one basic insight, one key awareness, that we humans have to learn, and learn quickly, to help us avoid catastrophe from climate change, nuclear weapons, spreading psychosis, and multispecies extinction?

Lacking inner truth, we’re compelled to be enablers of our suffering self.

I recently purchased a book titled A Gap in Nature: Discovering the World’s Extinct Animals, which has on its book jacket an artful rendering of a Dodo bird. When I was a young teenager, I spoke about this bird, this phoenix of Mauritius, at a school speaking contest. I mentioned that human interventions had wiped them out, and apparently my voice’s sorrowful mystification at that point convinced judges (did I guilt-trip them?) to award me first place.

I’m not mystified now as to why we might soon follow the dodo into the void. I understand why the human race is fated to self-destruct. The knowledge is found in depth psychology, which exposes our compulsion to recycle and replay unresolved negative emotions and to suffer the accompanying self-defeat. Are climate change and nuclear weapons just props or means we’ve created to act out this fate?

Our extinction can and must be avoided. We may be fated collectively to self-destruct, yet we’re not destined to do so. We’re destined, I’m sure, to create a world in which we become increasingly peaceful, united, and wise. When we learn, one person at a time, to see ourselves more objectively, with insight into our compulsion to act self-destructively, we acquire the knowledge and wisdom to fulfill our destiny.

The notion that our species is compulsively self-defeating and self-destructive has been explored extensively by psychoanalysts for more than 100 years. (Readers can find summaries of these discussions at Wikipedia, under repetition compulsion and death drive.) Many people desperately don’t want to believe we’re so foolish and obtuse. They can’t deal emotionally with inner truth, which is experienced as highly offensive to our ego and self-image. Even modern psychology denies the fact that hidden dynamics in our psyche make us our own worst enemy, claiming that such a contention blames the “poor” victims of emotional suffering for fostering their own misery.

Nobody is to blame. We don’t usually produce our suffering consciously. Emotional suffering and its accompanying self-defeating behaviors occur because the extensive inner conflict that simmers and often clashes in the psyche of most people operates beneath conscious awareness. Human beings are dodos when it comes to recognizing the various aspects of these inner dynamics.

When forced to acknowledge, say, the daunting mental health crisis, experts blame the problem on deviant genes, irregular brain chemistry, flawed thinking, bad parenting, poor leadership, and the stupidity or malice of others. The conflicted psyche mostly goes unmentioned. Little useful information is revealed in the media or in schools concerning how we ourselves unwittingly maintain and act out unresolved psychological dynamics that generate misery.

I couldn’t see inner conflict in myself for the longest time. Most people have more than one such conflict, and here was one of mine: Consciously, I very much wanted to feel my value, yet deep in my unconscious, at an emotional default position hidden from my awareness, I was strongly identified with myself as a person lacking in value.

Unconsciously, I looked for opportunities to feel this lack of value or respect. I didn’t understand at all my emotional attachment to this feeling. I took personally any slights from others or signs of their indifference. A sucker for suffering, I repeatedly jumped into the frying pan to simmer in the juices of unworthiness.

To cover up (defend against) my hidden willingness to endure this painful negative emotion, I would often blame others and get angry at them for supposedly disrespecting me. How clever of me to hide inner truth from myself! How self-defeating and self-damaging it was to go on deluding myself in this way! I simply didn’t have the self-knowledge that would have brought fuller intelligence to my rescue.

People don’t want to see how emotionally attached they are to various negative emotions, such as feeling unworthy, refused, deprived, helpless, criticized, rejected, abandoned, and unloved. Much of the time, we unconsciously indulge in these emotions. We cozy up to them at every opportunity. As just one example, we unconsciously engage in a psychological process called “negative peeping” whereby we look for situations in daily life that we interpret in such a way as to generate these negative emotions within us.

Parents aren’t to blame for this, though bad parenting can make things worse for us. Inner conflict originates in human nature, as an aspect of our biology, in a process that I describe in many of my books. We simply go on repeating, even when painful, what is unresolved. Sigmund Freud was right to call this dynamic the repetition compulsion. Very rarely now do psychotherapists disclose to their clients the facets of the repetition compulsion and the inner dynamics that generate negative emotions. Psychotherapists cannot help us find our inner truth until they, within themselves, have grappled with and made headway in overcoming this dark side.

It’s important now to distinguish self-sabotage from the underlying emotional attachments that are mentioned in italics two paragraphs above. Inner conflict consists of emotional attachments to those above negative emotions, while self-sabotage is the consequence of our entanglement in (and unconscious willingness to recycle) those negative emotions. Self-sabotage has, of course, a wide variety of manifestations, including anger, hatred, cynicism, greed, apathy, bitterness, regret, hopelessness, unworthiness, disconnection from self, lack of self-regulation, and impressions of being a victim.

As we study this knowledge, we can trace our self-sabotage back to its source. Our intelligence and wisdom are enhanced when we uncover within ourselves the hidden dynamics that have been supporting psychological dysfunction. We also expose the emotional-mental operating systems that have been supporting our defenses, projections, identifications, and transference, all of which have been undermining our intelligence. We manage to uncover and understand the biggest conflict of all, the daily battle between our inner passivity and our inner critic.

Learning all of this doesn’t have to be any harder than becoming adept at a new software program (providing we overlook unconscious resistance). The learning dismantles the primitive inner dynamics and empowers our intelligence. We connect with our authentic self and now have much greater capacity to flourish in life and to embody higher attributes.

We’re trying to raise our consciousness. Higher consciousness involves a growing range of understanding of what is real, true, and important. We might, for instance, understand that consciousness permeates all of life and that, as humans, we stand, in regards to our planet, at the apex of consciousness. Logically, this would make us custodians of the planet, just as we would hope that some sort of transcendent consciousness throughout and beyond our planet functions as custodian of our wellbeing and that of Earth.

Our consciousness can be elevated in a wide variety of ways. Anyone who tries with some success to live with kindness, to become wise, to honor the unity of life, and to resist the appeal of self-aggrandizement is becoming more conscious. Learning inner truth, the underlying facts concerning the operations of our personal psychology, also makes us more conscious.

When we’re inwardly conflicted, just living with kindness can be very difficult. Many well-intentioned people are unable to muster kindness and generosity. When inner conflict is not understood, negative emotions are likely to contaminate our perceptions and cast us into painful self-absorption.

Lacking deeper awareness, we’re compelled to be enablers of our suffering self. Humans have a mandate to become loving creatures, and inner truth expedites the process. Now more than ever our mind must seek inner truth because our spirit and planet are starving for more consciousness.

—

Read Peter’s latest book, Who’s Afraid of Inner Truth , at Amazon.com

.huge-it-share-buttons {

border:0px solid #0FB5D6;

border-radius:5px;

background:#3BD8FF;

text-align:left; }

#huge-it-share-buttons-top {margin-bottom:0px;}

#huge-it-share-buttons-bottom {margin-top:0px;}

.huge-it-share-buttons h3 {

font-size:25px ;

font-family:Arial,Helvetica Neue,Helvetica,sans-serif;

color:#666666;

display:block; line-height:25px ;

text-align:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul {

float:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li {

margin-left:3px;

margin-right:3px;

padding:0px;

border:0px ridge #E6354C;

border-radius:11px;

background-color:#14CC9B;

}

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li #backforunical2357 {

border-bottom: 0;

background-image:url('http://www.whywesuffer.com/wp-content...

width:30px;

height:30px;

}

.front-shares-count {

position: absolute;

text-align: center;

display: block;

}

.shares_size20 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 10px;

top: 10px;

width: 20px;

}

.shares_size30 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 11px;

top: 15px;

width: 30px;

}

.shares_size40 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 12px;

top: 21px;

width: 40px;

}

Share This:

July 25, 2018

Notes to Psychotherapists on Addressing Inner Passivity

Inner passivity and inner conflict cause a split in our sense of being.

Earlier this month I received an email from a young psychotherapist, in practice for just a few years, who was struggling to understand how, despite his best efforts, a client of his had committed suicide. He wrote, in part:

I recently experienced a therapist’s worst nightmare and lost a client to suicide. I’ve struggled to make sense of it as he exhibited almost none of the traditional warning signs. One thing I do remember about him is that he was very inwardly passive. Your writings have given me the clearest picture of his internal world, one of a harsh critic and a passive recipient. Nothing in my training even remotely addresses the passivity that I now think was a big part of his suffering. I look forward to reading more of your work and using it to help more people in the future.

Since this therapist is interested in applying this psychological knowledge in his practice, I can offer a few points to assist him and other therapists. My regular readers, meanwhile, can benefit from understanding more about inner passivity and the therapeutic relationship from the therapist’s point of view.

The individual in danger of committing suicide is likely to be inwardly weak and disconnected from self, unable to support himself or herself emotionally. (See an earlier post on the subject.) This weakness is a symptom of inner passivity, which I describe in my books and articles. Inner passivity operates as an enabler of our inner critic, and it’s a major factor in many kinds of dysfunction, including depression, anxiety, and addictions.

As my clients start seeing and understanding their inner passivity, they’re able to recognize it as a clinical condition and a universal peculiarity of human nature. With growing insight, they begin to see and feel the powerful influence of the passive side as they also shift away from their unconscious identification with it. As a benefit of this recognition, they start to detach emotionally from false impressions of themselves (such as impressions of being unworthy or a hopeless failure) that their symptoms have misled them into believing. In this process, their best self emerges from under the weight of painful and self-defeating symptoms.

Of course, psychotherapy that addresses inner passivity is not guaranteed to prevent suicide. Even the best psychotherapy won’t necessarily result in growth and healing with highly dysfunctional clients who usually need psychiatric interventions.

People seeking psychotherapy are typically healthy enough to benefit from it. Benefits of working deeply in the psyche are soon felt by clients as they acquire important self-knowledge, yet their unpleasant or painful symptoms usually persist, though to a gradually lessening degree. Effective therapy can take many months and sometimes years before clients heal their inner conflict and acquire inner peace. Nonetheless, these people are undergoing a major acceleration in self-development when compared to the many who, declining all psychological help, make little or no progress throughout their lifetime.

Many of the clients of a skilled therapist stay in the therapeutic relationship because they can feel and observe the progress they’re making and because they know the value of what’s being offered. Still, some people can’t or won’t do this deep therapy; they run away from this knowledge. The considerable resistance of these clients induces them to flee to another therapist or to quit therapy. Clients who are more dysfunctional or neurotic have more resistance and typically make slower progress. A therapist can be misled into the feeling of failing such a client, while all along the therapist’s effort might have helped the client to avoid increasing misery and self-sabotage.

A therapist gives every client the opportunity to overcome inner passivity and its accompanying inner conflict. The therapist does this by consistently and patiently presenting clients with evidence, as observed in the trials of their daily life and through dreams and memories, of their inner passivity and inner conflict. The therapist helps clients understand how their painful, self-defeating symptoms arise from inner passivity and inner conflict. In a manner that is largely mysterious, the assimilation of this deep knowledge, along with the effort that clients make in applying the knowledge to their daily life, become the antidote. Growing self-realization empowers clients’ intelligence, enabling them to navigate more astutely going forward as they connect with their best self and establish inner harmony.

Clients sometimes becomes defensive when their inner passivity is identified. Often, they feel as if they’re being judged or criticized when the therapist points out their inner passivity. As a form of resistance, they often tend at this point to deny that they’re passive, and they’ll verbalize as evidence the times when they have been assertive or aggressive (the examples they give are often of reactive and inappropriate aggression).

They react with this defensiveness because, inwardly, they experience defensiveness, usually unconsciously, when their inner critic scolds and mocks them for their inner passivity (and for their emotional attachment to it and identification with it). Therapists have to help clients understand the difference between the therapist identifying the influence of inner passivity in the client’s daily experiences and the inner critic berating an individual’s weakness in its role as inner tormenter and agent of inner conflict. Therapists sometimes have to reassure clients that their intention is not at all to be critical but only to probe for the influence of inner passivity so it can be made conscious and thereby overcome.

It’s the case that inner passivity is difficult to conceptualize. Therapists have to recognize it in themselves in order to convey the reality of it to others. Therapists can get a sense of it by detecting their own inner defensiveness, which is an inner reactivity based on their passive relationship with their inner critic or superego.

The therapist who teaches clients about inner passivity and shows evidence of it is also protecting himself from counter-transference, meaning in this case the therapist’s unconscious temptation (always present to some degree) to resonate with the clients’ sense of helplessness, failure, and unworthiness (again, all symptoms of inner passivity). Clients often try unconsciously to pull the therapist into the pain of their helplessness and failure and thereby have the therapist identify with them as victims. The therapist who does so validates their clients’ passivity rather than exposing it.

When therapists don’t see these deeper dynamics, they’re prone to professional burnout and weariness from the challenges of being a therapist. This reaction is especially likely when providing services to more passive or dysfunctional clients.

A client’s resistance is not a vexing annoyance for therapists once they have cleared out their own inner passivity. This inner freedom enables the therapist to be professionally detached, while operating with patience, compassion, and the courage needed to keep clients attuned to how their psyche’s inner dynamics generate suffering and self-defeat. It’s vitally important for the therapist to know how clients use unconscious defenses to cover up their collusion in the recycling and replaying of inner passivity and unresolved negative emotions. The therapist has to expose these defenses, often to the clients’ chagrin. As mentioned, clients typically have a love-hate relationship with inner truth. (Read, Get to Know Your Psychological Defenses.)

In my opinion, superficial approaches such as cognitive-behavioral therapy have risen to prominence in part because therapists trying to practice depth psychology were so frustrated by their clients’ unconscious resistance. The deeper we work in the psyche, the more resistance our clients are likely to produce within themselves. Cognitive-behavioral therapy is able to avoid triggering the resistance of clients because it doesn’t threaten to expose their deep attachments to unresolved negative emotions and their deep identification with inner passivity. Clients can be taught about resistance, and they can learn to observe it in order to prevent it from defeating their best intentions.

Unfortunately, the existence in our psyche of inner passivity is not being taught in our universities. To teach inner passivity or even acknowledge it, teachers have to be convinced of the truth of its existence. To know that truth, therapists have to access their own inner truth, and depth psychology can help us do this. Inner passivity usually only makes sense when we can see and understand its effects and dynamics within ourselves. Academic psychologists have been especially mentally oriented and, in championing superficial therapies such as behavioral and cognitive, they have inadvertently strengthened their ego rather than allowing themselves to be humbled by recognition of deeper knowledge and the extent of humanity’s blind spots.

This might all sound a bit complicated. But therapists can come into an easy understanding of these deeper dynamics, and acquire the ability to teach them, once they are working through, within themselves, their inner conflicts and their emotional attachments to the passive side. Therapists are, ideally, individuals who also have worked through their attachments to unresolved negative emotions such as refusal, helplessness, control, criticism, abandonment, and rejection. Typically, a therapist can only lead clients to the level of self-development that the therapist has personally attained.

I hope that the young therapist who inspired this post is at peace with himself concerning his client who committed suicide. I don’t believe he needs to think of this person as someone he “lost” to suicide. If at this point he’s burdened by a sense of failure, he might be allowing his inner critic, which can’t be trusted at all to be objective, to continue holding him accountable. It seems that he’s an earnest person devoted to becoming an excellent therapist. He can give value to the life of his former client in his caring, learning, and growing.

.huge-it-share-buttons {

border:0px solid #0FB5D6;

border-radius:5px;

background:#3BD8FF;

text-align:left; }

#huge-it-share-buttons-top {margin-bottom:0px;}

#huge-it-share-buttons-bottom {margin-top:0px;}

.huge-it-share-buttons h3 {

font-size:25px ;

font-family:Arial,Helvetica Neue,Helvetica,sans-serif;

color:#666666;

display:block; line-height:25px ;

text-align:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul {

float:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li {

margin-left:3px;

margin-right:3px;

padding:0px;

border:0px ridge #E6354C;

border-radius:11px;

background-color:#14CC9B;

}

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li #backforunical2353 {

border-bottom: 0;

background-image:url('http://www.whywesuffer.com/wp-content...

width:30px;

height:30px;

}

.front-shares-count {

position: absolute;

text-align: center;

display: block;

}

.shares_size20 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 10px;

top: 10px;

width: 20px;

}

.shares_size30 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 11px;

top: 15px;

width: 30px;

}

.shares_size40 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 12px;

top: 21px;

width: 40px;

}

Share This:

June 22, 2018

Are You Living Your True Story?

Everyone needs a story, as the saying goes. The best kind of story provides us with meaning and purpose, and it reflects values and beliefs to which we subscribe. Ideally, it tells us right from wrong, explains our suffering, and guides us going forward. Such stories, which go back in history to ancient creation myths, are cornerstones of our humanity.

The best kind of story provides us with meaning and purpose.

Many of us, in order to flourish, need to change our story. Some stories that people adopt (or are unconsciously burdened with) do their existence and intelligence a great disservice. “I am a worthless nobody and a loser” is a story that many people follow. Some people believe, as another common story, that they are the helpless victims of what is (or what they subjectively perceive to be) injustice and malice. Such stories develop out of our inner conflict, and invariably they produce self-defeat and self-sabotage.

Keep in mind that terrorists and criminals, along with greedy and self-aggrandizing people, operate according to stories that feel real and true to them. Sometimes the stories most fervently subscribed to are rationalizations for being cold-hearted and close-minded. We obviously don’t want to be acting out a story that incorporates a lack of belief or trust in oneself, is borrowed from others, or has been contaminated by unresolved emotional issues.

We can have more than one story at a time, a personal story, for instance, as well as a story that frames our worldview. It’s normal that our story would borrow heavily from parents and culture, even as we’re struggling to forge a unique, personal story.

History, science, politics, literature, and religion provide us with stories, as do the deeds and inspiration of friends, leaders, mentors, and teachers. A lot of influences bear down upon us as we construct a story that resonates with our time, place, and sense of self.

A good or true story, one that keeps faith with our potential, is obviously the best kind. How can we acquire or develop a story that we trust to be good and true? A personal story, if it’s to do justice to our humanity, usually needs to be aligned with inner truth. A test for the integrity and truth of one’s story is measured by how, as it unfolds, a person is liberated from inner conflict and negative emotions, thereby becoming more at peace with himself and others. What else could we trust to be true but a growing wisdom that is successfully lifting us out of misery and self-defeat?

Self-knowledge enables people to change their stories for the better. As an example of how this works, let’s look at a person who, deep within, resonates with feeling unworthy and unimportant. This individual, let’s call him Larry, is intelligent and holds a good job. Yet he’s anxious and distressed much of the time, and he’s aware of being highly sensitive to how he’s seen and regarded by others. Larry is thrilled to receive praise or even flattery, yet frequently he feels overlooked and unappreciated, which quickly brings up angry or critical feelings toward others. He is also chronically unhappy, plagued by a brooding sense of not living up to his potential.

Larry is living a false story. It doesn’t reflect the truth that, in his essence, he’s as worthy as any other person. It’s also a story his father lived, and it goes back generations.

Driven by this unhappiness, Larry seeks out psychological understanding of his predicament. He learns that he’s entangled in emotional conflict. While consciously he wants to be appreciated and to value himself, unconsciously he’s prepared to feel and know himself through negative emotions associated with feeling unworthy, weak, and unimportant. He’s also conflicted in another way: His unconscious identification with himself as being unworthy means that, in his psyche, he doesn’t possess the inner power to ward off his inner critic that assails him on a daily basis for his self-doubt and lack of confidence.

Larry learns that his anger at those who apparently treat him with indifference or disrespect covers up his emotional resonance with feeling himself to be unworthy or unimportant. This cover-up, the psychological defense, reads: “I’m not looking to feel unworthy or unimportant—Look at how angry (or critical) I get at those people who treat me that way.” (It’s very important to understand how we try to cover up, through psychological defenses, an awareness of our unconscious willingness to experience ourselves in negative ways.) As Larry sees his inner conflict more clearly, he begins to realize the underlying issue has little to do with others and instead is centered on his own tendency and even readiness to plunge into feeling unworthy or unimportant. He sees how he has been making a choice, albeit an unconscious one, to play up or embellish within himself these feelings of being unworthy. Now, with this growing insight, he begins to take ownership of (or take responsibility for) this dynamic in his psyche that has been inducing him to identify with being a lesser person.

This insight empowers his intelligence. Now, when triggered emotionally, he’s able to recognize his own participation in stirring up feelings of unworthiness. Larry realizes he has been choosing unconsciously to interpret various events and situations through feelings of being unworthy and unimportant, as if such negative emotions truly revealed his essence. His emotional identification with this irrationality had been overriding his common sense. He now realizes his anger at (or criticism of) those who allegedly see him in this negative light has been covering up his readiness to feel this way about himself. With this awareness, he begins to clear out his emotional attachment to feeling unworthy and unimportant. Soon, Larry is able to connect with his goodness and value, a connection that protects him from taking personally the real or perceived insensitivity or indifference of others.

A True Story for Us All

While individually we want to be in possession of a true story, we also need, as a human family, a true story that guides us all collectively. Such a story could originate from new insight—an epiphany concerning human nature—that awakens us to deeper self-realization. The knowledge is available and has been extracted here, at this website, from psychoanalytic literature. It reveals a critically important common denominator among the people of all races and nations. This knowledge, for starters, shatters the common story to which so many subscribe, that “I’m in too much pain and suffering, and infused with too much self-doubt, to do much good in the world.”

This knowledge about human nature can help to heal social and political dissension. The knowledge enables us to see the source of such dissension—along with anger, addictions, depression, and violence—in ourselves. Our new story now incorporates an awareness of the unconscious forces that have induced us to operate unwisely, incompetently, and foolishly—even to be our own worst enemy.

As the details of this unconscious functioning come into focus, we see precisely how we have been failing to connect with our better self. We now can begin to see, as we acquire this self-knowledge, how psychological dynamics have actively alienated us from our better self and from each other.

I write about this knowledge in my books and here on my website. In brief, human nature, as it manifests in our psyche, is inflicted with considerable conflict. The clearer each of us sees the specific dynamics of this conflict as it pertains to our personal life, the more quickly we are liberated from misery and suffering. The main aspects of this inner conflict are described here.

Another level of functioning in our psyche concerns our unconscious compulsion to act out (replay or recycle) the hurt of several unresolved negative emotions (other than feeling unworthy). Much of the time, we operate as if addicted to certain negative emotions. That process of emotional recycling, described here, produces a long list of painful symptoms (such as indecision, procrastination, worry, anger, bitterness, shame, guilt, loneliness, failure, addictions, and compulsions.)

With this knowledge, we realize we have been compulsively making unconscious choices to indulge in negative emotions and even to seek out or create situations in which we can experience and recycle these emotions. In recognizing this, we fortify our intelligence and strengthen inner resolve to avoid making self-defeating choices.

The most important psychological conflict is perhaps the one between the inner critic and inner passivity. The nature of this conflict is described here. This conflict is a main cause of anxiety, indecision, fear, low self-esteem, addictions, depression, and suicide. It is largely responsible not just for the cruelty and violence we act out against one another, but for cruel self-abuse such as chronic self-criticism, self-rejection, self-alienation, and self-hatred. With self-knowledge, we root out the negativity and self-doubt that inner conflict has been generating. When we clear up inner conflict, we discover our goodness and value. Our personal story, in all its richness, is now based on inner truth.

This knowledge from depth psychology is the story of human nature. It discloses our common humanity, while it exposes the lack of evolvement involved in being egotistical. We’re humbled and empowered as we come into acceptance of inner truth. With this knowledge, our map of the psyche is now more accurately outlined and our intelligence is greatly enhanced. For each of us, our personal story is more likely to be good and true when we access inner truth.

.huge-it-share-buttons {

border:0px solid #0FB5D6;

border-radius:5px;

background:#3BD8FF;

text-align:left; }

#huge-it-share-buttons-top {margin-bottom:0px;}

#huge-it-share-buttons-bottom {margin-top:0px;}

.huge-it-share-buttons h3 {

font-size:25px ;

font-family:Arial,Helvetica Neue,Helvetica,sans-serif;

color:#666666;

display:block; line-height:25px ;

text-align:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul {

float:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li {

margin-left:3px;

margin-right:3px;

padding:0px;

border:0px ridge #E6354C;

border-radius:11px;

background-color:#14CC9B;

}

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li #backforunical2343 {

border-bottom: 0;

background-image:url('http://www.whywesuffer.com/wp-content...

width:30px;

height:30px;

}

.front-shares-count {

position: absolute;

text-align: center;

display: block;

}

.shares_size20 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 10px;

top: 10px;

width: 20px;

}

.shares_size30 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 11px;

top: 15px;

width: 30px;

}

.shares_size40 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 12px;

top: 21px;

width: 40px;

}

Share This:

May 28, 2018

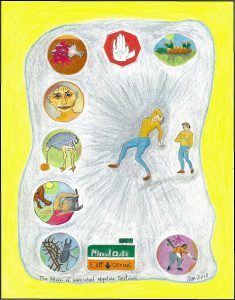

Another Visual Portrayal of Our Psyche’s Dynamics

Our body, mind, and psyche are fundamentals of our existence. Our body is visible to us and our mind is at our disposal. But our psyche tends to hide in the mist of our unconscious, like the hint of a person lurking in the background of a dream.

This image depicts our unconscious tendency to gravitate toward unresolved negative emotions.

When we don’t know basic facts about our psyche, we find it harder to connect with our deeper, better self. We’re then at the mercy of inner turmoil when our psyche is conflicted, as it is to some degree in just about everyone.

The psyche is the repository of forces, dynamics, and conflicts—largely unconscious—that influence and even determine our personality, behaviors, thought processes, and prospects for success and happiness. Misery and self-defeat arise from any dysfunction occurring in our psyche. Knowing more about our psyche is obviously important.

Our psyche becomes apparent and accessible to us—not visually but as a new awakening of our intelligence—when we learn and see how the principles of depth psychology apply to us personally.

Learning about the psyche is challenging because we can’t put it under a microscope and study all its aspects. What exactly is it anyway? We can’t even say whether our psyche is an entity within us, an energy field swirling around us, or some other mysterious configuration.

In this post, I’m presenting an illustration that depicts a major operating system of our psyche. This illustration (drawn and colored by me in my folksy style) depicts our unconscious tendency to become entangled in unresolved negative emotions. (Click to enlarge image.) I recently published another visual portrayal of the psyche (in a post titled, Illustrating the Characters Who Mess with Our Mind), along with a written explanation of what is portrayed. My latest artwork, published here with this post, provides another overview of how our psyche works. Over the years I’ve written extensively about all of these dynamics, and I’m hoping that this visual portrayal and the one published earlier will help readers make sense of depth psychology.

This latest “map” is titled, “The Allure of Unresolved Negative Emotions.” It portrays at its center a female figure, representing humankind, in anguish over her compulsion to experience (and to suffer with) various negative emotions that are unresolved in her psyche. The young person coming up behind her informs us, in all her innocence, that these negative emotions and our attachment to them emerge from our past, from human nature itself, and that no one is to blame for what is, above all, a testament to humanity’s unfinished state of evolvement.

The turtle flailing helplessly on its back in the upper-right corner represents the negative emotion of helplessness, as well as our unconscious attachment to that emotional state. This negative emotion is one of the primary symptoms of inner passivity and it contributes to a wide range of self-defeating behaviors. (Read more about helplessness and inner passivity here and here.)

Moving counter-clockwise, the stop sign symbolizes the negative emotion of refusal. From an early age, children can be very sensitive, as parents know, to feeling refused. A child wailing in a toy store or in the candy aisle at the supermarket is vigorously protesting against the feeling of being refused. As adults, we can still resonate with feeling refused, even in situations where refusal is not an actual intention or even a reality. When we resonate emotionally with an old association such as refusal, we’re likely to get triggered and thereby be in emotional and behavioral jeopardy. (This post deals with the emotional attachment to refusal.)

To the left is an image of a broken wine bottle, symbolizing our psyche’s readiness to seize emotionally upon the feeling of loss. All of us have occasions to feel loss, but our psyche is often prepared, when we’re not inwardly observant and informed, to embellish the feeling of loss and to compel us to indulge emotionally in that feeling. Doing this is obviously unpleasant if not painful. (Read more here about how our psyche embellishes feelings of loss.)

Next, the rendition of Gollum from “The Lord of the Rings” symbolizes the negative emotion of powerlessness. This negative emotion is somewhat similar to that of helplessness, as depicted in the turtle image. One difference is that the individual attached to powerlessness is more likely to constantly crave power and to seek to control others, while the person entangled in helplessness, while sometimes craving power and pursuing it inappropriately, is more likely to act out by being chronically weak and helpless in various situations. Gollum frantically pursues the ring of power as a reaction to (and compensation for) his emotional entanglement in feelings of powerlessness. (More here.)

The next image, of an ostrich with its head buried in the sand, signifies abandonment. Our psyche is instinctively sensitive to the feeling of abandonment. The inner passivity lodged from childhood in our psyche contributes to this feeling. The prospect of abandonment is horrifying to little children, and these emotional associations linger in adults. The ostrich has its head in the sand because abandonment, as an emotional issue for adults, is most commonly experienced as self-abandonment. This is felt, for instance, when we’re not present to support ourselves emotionally through difficult times. Knowing ourselves through self-doubt, self-alienation, and a painful disconnect is a common default identity. (Read about it here and here.)

In the next image, a woodsman is fending off a ravenous wolf. The wolf signifies rejection and the image itself symbolizes self-rejection. Though consciously we want to respect and love ourselves, we unconsciously become entangled in old emotional associations having to do with feeling rejected. People can be overly sensitive to feeling rejected, and they can create that painful impression in relationships even when rejection is not actually intended or occurring. The problem largely stems from self-rejection, experienced primarily by way of the inner critic that is often harsh, cruel, and demeaning. (More here.)

The beetle in the thorn bush, in the next image, represents self-criticism. The originator of self-criticism is, of course, the inner critic. Our inner passivity also contributes to the problem in allowing our inner critic to get away with its unwarranted intrusions into our emotional and mental life. Just as we can be rejecting of ourselves, we can also be critical of ourselves. The scale of negativity intensifies as follows: self-criticism, self-rejection, self-condemnation, self-hatred. Someone who is attached emotionally to feeling self-criticism will, at the same time, be inclined to be compulsively critical of others. (More here and here.)

Next is a highway exit sign, with “Missing Out” as a term to denote our psyche’s readiness to experience deprivation. This negative emotion—the painful impression that one is missing out on some goal, reward, or benefit—is very common. Even prosperous people get entangled in its painful clutches. When we’re disconnected from our authentic self and frantically pursuing material benefits and overvaluing non-essentials, we’re bound to feel we’re missing out on something important. This negative feeling haunts us as our psyche clings to it, and we become increasingly unhappy. (Read more here.)

The final image shows a man stabbed in the back, with a shadowy figure lurking above him. The image represents betrayal as well as self-betrayal. An individual can easily feel betrayed through the behavior of others—again, even when betrayal is not intended. Our psyche can eagerly embellish a sense of betrayal when inner conflict, in the form of unconsciously expecting and looking for betrayal, prevails. More profound and even more painful, though, is self-betrayal, which opens a whole field of consideration involving self-defeat and self-sabotage. (Read more here.)

I have not discussed anywhere in this illustration and post the negative emotions of anger, hatred, bitterness, jealousy, envy, cynicism, loneliness, hopelessness, apathy, boredom, and depression. That’s because these negative emotions, along with various behavioral problems, are simply symptoms of the primary negative emotions that are discussed above. It’s important to understand that anger, as one example, is a symptom of one’s unconscious willingness to indulge emotionally in helplessness (or refusal, loss, powerlessness, self-abandonment, rejection, criticism, deprivation, and betrayal.) The anger is a cover-up, a defense. The unconscious defense proclaims: “I don’t want to feel helpless (or whatever). Look at how angry I am at those people who want to restrict me, hold me down, or oppress me.” Or, ”Look at how angry I am at myself for helplessly procrastinating and being indecisive.” (Read about how our defenses work here.)

The dynamics outlined by this portrayal of the psyche, along with its accompanying text, operate like a software program that runs our emotional life. Obviously, the program needs to be updated, which our intelligence is quite capable of doing. To help make sense of how the two illustrations (this one and the first one published earlier) relate to one another, the first can be regarded, metaphorically, as depicting the hardware of the psyche, while the second, in this post, portrays not the hardware but the software running the emotional life of our psyche. The hardware-software analogy is not entirely accurate because the aspects or characters depicted in the first illustration are not hard-wired or inalterably embedded. They do themselves become modified for the better as our self-development progresses. Still, I believe the analogy provides a helpful perspective for understanding how the two illustrations can be viewed as a whole.

Finally, a person struggling with emotional or behavioral problems will typically be attached to three or four of these primary negative emotions depicted in the latest illustration. When we identify these emotions in ourselves, we’re able to observe going forward our readiness, willingness, and even unwitting eagerness to experience them. We can now take responsibility for what had previous been operating compulsively at an unconscious level. Our intelligence is empowered, as well as our will to flourish as we start to see clearly the unconscious “mischief” that was getting us in trouble.

.huge-it-share-buttons {

border:0px solid #0FB5D6;

border-radius:5px;

background:#3BD8FF;

text-align:left; }

#huge-it-share-buttons-top {margin-bottom:0px;}

#huge-it-share-buttons-bottom {margin-top:0px;}

.huge-it-share-buttons h3 {

font-size:25px ;

font-family:Arial,Helvetica Neue,Helvetica,sans-serif;

color:#666666;

display:block; line-height:25px ;

text-align:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul {

float:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li {

margin-left:3px;

margin-right:3px;

padding:0px;

border:0px ridge #E6354C;

border-radius:11px;

background-color:#14CC9B;

}

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li #backforunical2338 {

border-bottom: 0;

background-image:url('http://www.whywesuffer.com/wp-content...

width:30px;

height:30px;

}

.front-shares-count {

position: absolute;

text-align: center;

display: block;

}

.shares_size20 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 10px;

top: 10px;

width: 20px;

}

.shares_size30 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 11px;

top: 15px;

width: 30px;

}

.shares_size40 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 12px;

top: 21px;

width: 40px;

}

Share This:

April 25, 2018

Get to Know Your Psyche’s Operating Systems

People tend unconsciously to falsify reality. We’re usually not aware of how and why our sense of reality is distorted, which is an impediment to our intelligence.

Separate operating systems in our psyche can distort our objectivity.

What’s causing this distortion of reality? At play in our psyche, with distinct and separate “operating systems,” are the inner critic, ego, id, psychological defenses, inner passivity, and resistance. Not only do these systems tend to operate outside our awareness, they’re also at odds with one another as they churn up inner conflict, negative emotions, and self-defeating behaviors. I have illustrated and described them here as aspects or “characters” of our psyche.

As we grow psychologically, a dominant and healthy inner operating system arises from our solid connection to (and embrace of) our authentic self.

For this article, I focus on the operating system known as inner passivity. It’s the least well-known and perhaps the most problematic of these inner systems. This passivity, which affects almost everyone, is a mental-emotional state of mind through which we stumble into suffering and self-defeat. Humankind has not yet begun to appreciate this aspect of our human nature.

We are in the throes of this passivity when we interpret situations and challenges through feelings of being overwhelmed, helpless, indecisive, trapped, constrained, restricted, controlled, held accountable, required to submit, and otherwise victimized.

Inner passivity also causes us to succumb weakly to cravings; to be cynical or bitter concerning defeats and failures; to fail to represent ourselves effectively in social situations or in fulfilling our aspirations; to be riddled with self-doubt; to chronically feel unsupported and unappreciated; to feel at the mercy of fate; and to allow our inner critic to disparage and belittle us. The list goes on.

People are obviously not as passive as sheep. Even the most passive among us have, of course, much more consciousness and brain power. But just as sheep are unaware of their passive nature, we humans are likewise unaware of how passively we experience ourselves and much of what transpires around us.

People are usually not even aware of the existence in their psyche of inner passivity, though it profoundly contaminates our thinking and limits our ability to act in our best interests. Once we grasp a mental understanding of it, we still have to become aware on an experiential level of the degree to which we are under its influence.

One client said in a note to me: “I continue to find it difficult to feel and identify when I’m experiencing inner passivity. I know, on an intellectual level, that I experience it. The patterns of my adult life clearly attest to its existence: ongoing feelings of indecision about what to do or where to go; constant procrastination with important projects; a chronic pattern of starting projects (and wishing to use my full potential) and yet never following through.”

Yes, even as we start to consider and study inner passivity, our intelligence still struggles to bring its existence into focus as an entity with its own operating system. We have trouble, for one thing, separating our sense of self from the symptoms (as listed at the beginning of this article) that this passivity generates. The symptoms give our inner critic fuel to disparage and condemn us, and we become passive to our inner critic, blindly entangled in the conflict between our aggressive critic and our defensive passivity.

Our defenses (another inner operating system) adamantly cover up this passivity. The common unconscious defense is to claim: “I’m not passive—if anything, I’m aggressive.” This reactive aggression, however, is often inappropriate and self-defeating. An individual might also defend by saying: “I’m not passive: Look at how angry I get when someone tries to control me.” This angry reaction is often negative and self-defeating.

We’re fooled by these defenses, and inner passivity is shrouded over. As we proceed under its influence, we’re likely to feel we’re just being who we are, as if everything is either normal or what we’re fated to experience, in the way it’s normal for sheep to be passive.

As it is for sheep, our passivity is largely biologically rooted. Yet we have knowledge and consciousness on our side, if we can overcome our resistance to accessing it. Human passivity might have been acceptable before we became capable technologically of destroying the world, but now this flaw in human nature has become very problematic. As a blind spot in dealing with reality, it makes us dangerously dysfunctional, likely to be overwhelmed by the cultural, political, and social upheavals being produced by accelerating technology and climate change.

Often inner passivity is influencing us in ways that are quite subtle, so seeing it requires insight. That insight is more than just a mental connection—it’s also an intuitive realization, a synergy of memories and experiences, a jolt of consciousness. At some point, to see this passivity is to marvel at the fact that we were previously so oblivious of it.

Some examples follow that can guide readers in tracking their own passivity. One reader, noting her growing awareness of her passive side, asked me, “Do you think it’s possible to completely heal and break free from inner passivity? I’m dealing with this in therapy right now, and it seems almost as if I have to eliminate inner demons associated with codependency to awaken my authentic self. I know inner passivity is easy to fall back on, but I’m wondering if it’s possible to 100 percent break free and not turn back?”

I wrote a note back to her, saying: “You asked if it’s possible to 100 percent break free of inner passivity and not turn back? You want to consider why you’re asking this question in the first place. The question itself arises from a passive place inside you.

“It is likely,” I wrote, “that you’re asking this question because to ponder it enables you to indulge in, or flirt with, the helpless feeling that you might never be able to free yourself from inner passivity. Otherwise, why ask the question? Who knows whether you’ll achieve 100 percent elimination of it. That’s not important. What’s important is that you get started doing your best to recognize and address it.”

I added: “Understanding that your question arises out of inner passivity is an important insight for you: You can now see one of the ways in which you experience yourself and life through inner passivity. You see how you frame things in a passive way, a way that leads you to doubt yourself and distrust the future. Seeing and exposing inner passivity in all its subtle variations is an act of power and determination that leads you toward inner freedom. Keep reading about it. Be vigilant every day to observe how it creeps into your thoughts and feelings.”

Another visitor to my website commented: “Since I can remember I was creatively active in writing, painting or sculpting. I have a wide range of interests I researched and spent time reading up on. A few years ago, I started to feel like none of my artistic endeavors have any use or meaning anymore. I do have the energy and inspiration, but as soon as I start to act upon it, I am overcome by a sense of meaninglessness. It feels useless and without any contribution to society, it feels selfish.”

He added: “I am aware this is some form of excuse, but I can’t shake the feeling and enter the creative flow as I used to. Even if I am brimming with creative inspiration or curiosity to research my interests, I am holding myself back and literally just hope the day finishes up quickly so I don’t have any time to engage with these activities. I hope there are some things that I can become aware of, in order to find a way out of this conflict.”

In reply, I told him: “It is common, as an aspect of human nature, for people to experience themselves in a passive way. Even when we’re skilled and talented, or have great potential, we can find ourselves, as you described it, unable to connect with a capacity to turn this potential into action and achievement.

“What you want to do at such moments is take the focus off the actual objective (in your case, artistic fulfillment and achievement) and instead focus your attention and growing understanding on the underlying passive feeling. You would likely have this same passive feeling if you were striving for some other goal, other than being an artist.”

I added: “This feeling of helplessness and weakness operates like an emotional addiction. It’s called inner passivity, and it contaminates, in varying degrees, the human psyche. It’s a default position within you, a leftover emotional association from the long years you spent during childhood in relative states of helplessness and dependency. You have to outgrow, through psychological knowledge, what is basically an impairment caused by human biology. A sheep can’t overcome the passivity of its biology, but we humans, to a considerable extent, can do so.

“To see the passivity within you, and to feel it and understand it when you’re in the throes of feeling stuck or unmotivated, is an act of power. It means that you’re expressing determination in that moment to overcome it. Otherwise, you would be in denial—you would not want to see, with such clinical awareness, the nature of this passivity. When you strive for self-understanding and make every effort to see the passivity as a clinical problem that you can remedy, you’re declining to go on suffering needlessly. You’re saying NO to the temptation to be pulled into this weakness, self-doubt, and disconnect from self.”

In another situation, a client was telling me his thoughts about rekindling his relationship with an ex-girlfriend. But he hedged as he spoke, going back and forth for several minutes about whether he would or he wouldn’t start seeing her again.

“Do you see what’s likely happening right now,” I said. “You’re probably looking for me to push you in one direction or another. As we know from your past, you’ve been passive to people who try to exert influence over you. You’re flirting emotionally right now with the passive feeling of having me influence you one way or the other.

“Then you can feel passive to my influence. Were I to take the bait and tell you what I thought you should do, you might passively accede to what I say or you might passively-aggressively resist what I recommended. Either way, your unconscious game is to feel passive to my influence. Realizing this helps you to understand how inner passivity, as an unconscious operating system within you, permeates your way of thinking and feeling.

“If I were to give you advice, pushing you in one direction or the other, it would not address your underlying passivity. I don’t give advice. Instead I help you acquire self-knowledge and insight, so you can make your own wise decisions about how best to live your life. That capacity arises within as you overcome the influence of inner passivity.”

Some people feel that the effort involved in self-development is overwhelmingly monumental. They feel they just don’t have what it takes to succeed. This negative feeling is, of course, just another way to experience inner passivity. Do you see how that passive feeling sneaks in wherever it can? With clinical knowledge of inner passivity, we become a detective in our own psyche, an observer of what had previously been shrouded in unconscious darkness. Our consciousness is enhanced. Now we proceed with a sense of purpose and direction, accompanied by feelings that we’re doing our best—all much more pleasant than being passive.

—

Peter Michaelson is the author of The Phantom of the Psyche: Freeing Ourself from Inner Passivity.

.huge-it-share-buttons {

border:0px solid #0FB5D6;

border-radius:5px;

background:#3BD8FF;

text-align:left; }

#huge-it-share-buttons-top {margin-bottom:0px;}

#huge-it-share-buttons-bottom {margin-top:0px;}

.huge-it-share-buttons h3 {

font-size:25px ;

font-family:Arial,Helvetica Neue,Helvetica,sans-serif;

color:#666666;

display:block; line-height:25px ;

text-align:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul {

float:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li {

margin-left:3px;

margin-right:3px;

padding:0px;

border:0px ridge #E6354C;

border-radius:11px;

background-color:#14CC9B;

}

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li #backforunical2323 {

border-bottom: 0;

background-image:url('http://www.whywesuffer.com/wp-content...

width:30px;

height:30px;

}

.front-shares-count {

position: absolute;

text-align: center;

display: block;

}

.shares_size20 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 10px;

top: 10px;

width: 20px;

}

.shares_size30 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 11px;

top: 15px;

width: 30px;

}

.shares_size40 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 12px;

top: 21px;

width: 40px;

}

Share This:

March 27, 2018

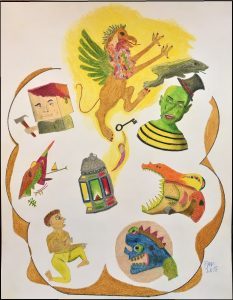

Illustrating the Characters Who Mess With Our Mind

A visual image can help us recognize the main players in our psyche.

I’ve been slowing down my writing production over the past year, as my mind and psyche shift away from the mental side into more intuitive and contemplative states. For many years I’ve been “drawing” portraits of the psyche in the language of depth psychology—with words, phrases, theory, examples, and explanations.

As I write, I try to express my words artfully, but here I’ve also added artwork that illustrates some of the dynamics of inner conflict and human dysfunction. (The illustration I’ve done here is a bit washed out–the original looks better.)

This artwork still needs text to explain what is portrayed, and this post provides that information. The image (click to enlarge) has eleven characters and symbols. It is missing a background: my artistic ability is awaiting further development.

Seven of these images represent troublesome parts of our psyche. For whimsy’s sake, call them the Seven Dworks. They’re like renegade operating systems, totally out of harmony with one another and with our better self. The four other depictions represent what is good, creative, and great about us. I’ll say a tiny bit about each of these—and save the best for last.

Let’s start with the gruesome figure at bottom right. It represents our nasty, primitive inner critic, the seat of self-aggression. It (it’s certainly not a he or she) is wearing a crown because it assumes to be our rightful voice of authority, although its power is irrational, illegitimate, and downright abusive.

To the left of it is a deformed human figure that depicts inner passivity. This weak aspect of ourselves is a defensive, anxious enabler of the inner critic. In its conflicted dynamic with our inner critic, inner passivity represents our best interests very badly. Recognizing our inner passivity is so important in overcoming our suffering. We have to bring more consciousness to the ways this particular influence affects how we experience ourselves and the world. (I could also have drawn this character as a phantom, as per my book, The Phantom of the Psyche: Freeing Ourself From Inner Passivity.)

Directly above inner passivity, floating around in our inner space, is an image representing the ego. Many people, to some degree or other, identify with their ego. Though it’s just an illusion of our real self, many spend their lifetime fiercely feeding it flimsy validations and anxiously safeguarding it.

Above the ego, the character with the cubic head stands for our unconscious resistance. This stubborn blockhead refuses to accept or integrate the knowledge that leads to self-development. The hammer represents inner resistance’s willingness to endure self-sabotage in preference to considering liberating knowledge. (In future depictions, I might give it a raised left fist of obstinate defiance, once I become a better drawer of hands.)

Over on the other side of this artwork, directly above the inner critic, is the id, the psyche’s ravenous brute. The id manifests most strongly in people who are grasping, self-aggrandizing, filled with desire, and tortured by what they feel they’re not getting. Rambunctious capitalism that assails Mother Nature is a derivative of the frenzied id.

Above, with its hat askew, is the trickster, representing our psychological defenses. In fact, our defenses mostly arise out of inner passivity (lower left). However, inner passivity represents much more than our defensiveness, so I thought it would be helpful for the purposes of this portrayal of the psyche to have a special character, a trickster, serving as the symbol for how we inwardly fool ourselves and cover up inner truth through our defense system.

Knocking the trickster’s hat askew and fleeing the scene is the rogue rat of the psyche, the negativity that arises from inner conflict and contaminates our emotional life. As we’re doing inner work, this negativity diminishes. As we’re reaching our potential, negativity is banished from our inner life, no longer able to poison our daily experiences with anger, shame, guilt, moodiness, depression, indecision, cynicism, loneliness, cravings, and so on.

We don’t want to regard these seven characters from our psyche as horrible or wicked. We don’t want to start a fight with any of these parts. We just want to expose them, keep an eye on them, realize their primitive nature, and understand their underlying agendas and conflict. As we achieve inner progress, they’ll be integrated and sublimated. Under cover of our ignorance, however, these aspects all want to be experienced. They’re eager to flare up, and they’ll seize any opportunity, any situation or event from our daily life, to make their presence felt.

Let’s now look at the more favorable aspects of the psyche. At the center of the drawing is a lamp, with a small flame burning inside. The lamp and the flame represent our latent self. We all have the flame of potential self-actualization burning inside of us.

As the flame begins to flare more brightly, a small figure, our emerging self—inspired perhaps by courage, honesty, and kindness—arises from the lamp. This fledgling self is reaching for a key, a symbol for the deeper knowledge that reveals the nature of our psyche and how it operates. The key is vitally important. If the dynamics of our psyche operate in secret beyond our awareness, we’ll find it more difficult to emerge from suffering. The knowledge of depth psychology, symbolized by this key, can be found in the posts on this website and in my books.

The final figure, rising above the key, is a griffin. This creature of fable is symbolic of the sun. Among the Greeks, it symbolized strength and vigilance. It’s also a symbol of resurrection and divine human nature. The griffin represents our actualized self, and here it’s heralding the establishment and flourishing of our best nature and the victory of self-realization.

Knowledge is power, and self-knowledge, our awareness of inner dynamics, is empowerment of the self. Specific knowledge concerning each of the characters I’ve portrayed here is described in detail in my writings (except that I don’t specifically mention a trickster in my discussions of the defense system).

If you have any thoughts, questions, or suggestions, let me know. I might be able to incorporate what you have to say in future illustrations.

.huge-it-share-buttons {

border:0px solid #0FB5D6;

border-radius:5px;

background:#3BD8FF;

text-align:left; }

#huge-it-share-buttons-top {margin-bottom:0px;}

#huge-it-share-buttons-bottom {margin-top:0px;}

.huge-it-share-buttons h3 {

font-size:25px ;

font-family:Arial,Helvetica Neue,Helvetica,sans-serif;

color:#666666;

display:block; line-height:25px ;

text-align:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul {

float:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li {

margin-left:3px;

margin-right:3px;

padding:0px;

border:0px ridge #E6354C;

border-radius:11px;

background-color:#14CC9B;

}

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li #backforunical2310 {

border-bottom: 0;

background-image:url('http://www.whywesuffer.com/wp-content...

width:30px;

height:30px;

}

.front-shares-count {

position: absolute;

text-align: center;

display: block;

}

.shares_size20 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 10px;

top: 10px;

width: 20px;

}

.shares_size30 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 11px;

top: 15px;

width: 30px;

}

.shares_size40 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 12px;

top: 21px;

width: 40px;

}

Share This:

February 21, 2018

How to Love Yourself

A lot of people struggle with the challenge of trying not only to feel good about themselves but, more urgently, trying to avoid feeling bad or really bad about themselves.

Being a loving person is our birthright. But we still have to make it happen.

When individuals understand the primary psychological dynamics that produce self-doubt, self-criticism, self-rejection, and even self-hatred, they can escape from these negative feelings and begin to appreciate themselves in an accepting and loving way.

Being a loving person is our birthright. This ability comes naturally when we clean house, meaning when we identify and resolve the inner conflicts that produce negative emotions.

You can get to love by looking at the inner dynamics that cause you to dislike yourself. Feeling bad about oneself usually arises from an inner conflict involving feelings of being unworthy, unimportant, and deserving of disrespect. What exactly is the conflict? Consciously, we want to feel good about ourselves but many of us still resonate emotionally with (or identify with) the feeling that being disrespected and unworthy is somehow true to the essence of who we are.

Why is this? When we’re feeling bad about ourselves on a daily basis, the most likely culprit producing these bad feelings is self-aggression. This self-aggression is a byproduct of the natural biologically endowed aggression that human beings have required in order to survive. Our ancient ancestors were very aggressive as hunters and defenders of their territory. This aggression has been modified and tempered by civilization. Religious principles have at times helped to contain this aggression, as have legal systems, educational achievement, social and cultural norms, and the threat of punishment and imprisonment. Yet our innate aggression still exists as part of our biology, and we can obviously see evidence for it in the extent of domestic and international dissension and strife.

Keep in mind that healthy aggression can produce much pleasure, as in competitive sports, in striving to excel, and in expressing our voice effectively in the world. But a flaw in our emotional nature causes some of this aggression to be directed against us personally. Inwardly, we unwittingly absorb accusations of alleged unworthiness and weakness from our inner critic (also known as the superego). These accusations are irrational and often cruel and abusive. Because we don’t see these inner dynamics clearly enough, we fail to protect ourselves from the intrusions and abuse instigated by our inner critic.

We become our inner critic to ourself, meaning it feels as if our frequent belittling and devaluing thoughts and feelings originate in our mind as a legitimate self-evaluation. One key insight: Our inner critic has no business butting into our life and holding us accountable for what we’re doing or thinking. (The inner critic is not our conscience, the natural authority that tries to guide us wisely.) Because we lack vital self-knowledge, our inner critic gets away with being abusive and demeaning.

The inner critic is a primitive aggression that has no sensitivity to our wellbeing. But only you or I, through inner awareness, can protect ourselves from its intrusions. We can neutralize or deflect self-aggression as we expose its irrationality and stand up on an inner level to its authoritarian, cruel, and tyrannical character.

On the other side of this inner conflict is inner passivity. Sometimes people are aware of their self-aggression, but they seldom see or understand their inner passivity. Through inner passivity, we become enablers of the self-aggression. We fail to deflect or neutralize the self-aggression because our inner passivity blocks us from awareness of our capacity to do so. Inner passivity even blocks us from seeing the inner critic as an unwarranted inner bully. Inner passivity is like a foggy area in the no-man’s-land of our psyche. To our still evolving consciousness, it’s terra incognito. But as we become aware of this inner passivity and its operating procedures, we begin to know and realize the existence of new reservoirs of inner strength.

Consciously, we certainly do want to feel good about ourselves. Unconsciously, however, we’re so used to being on the receiving end of self-aggression and its disparaging thoughts and feelings that this inner predicament feels natural to us, as if this is who we are and how things are supposed to be.

As a result, being in conflict, however painful that is, all feels natural somehow. We become the embodiment of this primitive configuration in our psyche. We have no idea how it could be different or better for us.

This all means, basically, that we’re attached emotionally to being on the receiving end of accusations and allegations of our alleged wrongdoing and inadequacy. It means that we’re attached to feeling ourselves at the mercy of this aggression. It also means that we resonate emotionally with feeling that others see us as if we are indeed unworthy and deserving of disrespect.

People refuse to see their emotional resonance with these painful feelings because of their resistance to being humbled by recognition of this stubborn perversity in human nature. Instead, they insist they want to be admired and respected. Their psychological defense goes like this: “I feel so good when I’m liked and admired by others. I love it. That proves I want to be admired, not disrespected!” This defense covers up a person’s inner truth, namely the existence of an emotional attachment to feeling disrespected and unworthy, even as we try to live so as to be admired. Also impeding inner progress is fear of change and resistance to breaking one’s identification with the inner status quo.

At this point, a person can employ another unconscious psychological defense that claims, “No, I don’t want to be disrespected or devalued! Look at how upset and angry I get at those who do it to me! That proves I’m not looking for the feeling.” Fooled by this defense, we’re going to have a hard time maintaining that loving feeling.

We can sometimes feel bad about ourself even without much intrusion from our inner critic. This can happen simply because our inner passivity, all by itself, has us stuck in indecision, procrastination, recurring failure, worry, confusion, apathy, cynicism, and helplessness. Our inner critic, though, is always eager to butt in with its bitter mockery, kicking us when we’re down.

We become more loving by becoming stronger on an inner level. This happens as we go inward to eliminate the negative thoughts and feelings that churn around in our emotional life. To some degree, everyone has unconscious attachments to certain negative emotions that were initially experienced in childhood and which remain unresolved in the adult psyche. The post, How to Be Your Own Inner Guide, will help readers understand these unpleasant and often painful emotions and learn how to overcome them.

The main inner conflict in the human psyche is between self-aggression and inner passivity. It produces the effect of wanting to feel strong while identifying with feeling weak and helpless. The conflict means we consciously want respect while unconsciously anticipating disrespect. Other variations on this main conflict include: wanting to be loved but expecting to be rejected; wanting to feel fully satisfied yet looking for the feeling of being deprived; wanting to get but prepared to feel refused; wanting to be decisive but identifying with feeling indecisive; wanting to be in control but expecting to be controlled; and wanting to feel connected to self but prepared and even determined to feel disconnected, betrayed, and abandoned.

As we see the dynamics of inner conflict, we expose our blind spots. This empowers our intelligence, strengthens our rationality, and establishes a solid inner foundation on which we can fully respect and love the creature we are.

We live in a world where truth and reality are being challenged by many forces and developments. Inner truth is the foundation of wise discernment that guides us forward. When we explore our psyche, we can heal inner conflict, establish greater harmony and integrity, and uncover the inner truth that liberates our best loving self.

.huge-it-share-buttons {

border:0px solid #0FB5D6;

border-radius:5px;

background:#3BD8FF;

text-align:left; }

#huge-it-share-buttons-top {margin-bottom:0px;}

#huge-it-share-buttons-bottom {margin-top:0px;}

.huge-it-share-buttons h3 {

font-size:25px ;

font-family:Arial,Helvetica Neue,Helvetica,sans-serif;

color:#666666;

display:block; line-height:25px ;

text-align:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul {

float:left; }

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li {

margin-left:3px;

margin-right:3px;

padding:0px;

border:0px ridge #E6354C;

border-radius:11px;

background-color:#14CC9B;

}

.huge-it-share-buttons ul li #backforunical2306 {

border-bottom: 0;

background-image:url('http://www.whywesuffer.com/wp-content...

width:30px;

height:30px;

}

.front-shares-count {

position: absolute;

text-align: center;

display: block;

}

.shares_size20 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 10px;

top: 10px;

width: 20px;

}

.shares_size30 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 11px;

top: 15px;

width: 30px;

}

.shares_size40 .front-shares-count {

font-size: 12px;

top: 21px;

width: 40px;

}

Share This:

January 19, 2018

Don’t Let Inner Passivity Undermine Democracy

Most people, including mental-health professionals, are unaware of how strongly we know ourselves and identify with ourselves through a condition of non-being known as inner passivity.

Democracy depends on your efforts to grow psychologically.

This mental and emotional identity is a widespread psychological condition that’s largely unconscious. We aren’t aware of how much it causes us to feel self-doubt, to question our value, and to disconnect from our best self. In this way, inner passivity undermines the qualities that a democracy requires of its people.

Inner passivity blocks us from accessing our integrity, dignity, courage, compassion, moral intelligence, and love. As we begin to see and understand our inner passivity, we become aware of vital knowledge concerning inner conflict and psychological dysfunction.

Our democracy needs the deeper knowledge that exposes this passivity. As we grow into a recognition of our inner passivity, we begin to understand the psychological undercurrents of ongoing conflict in our own psyche and in the dynamics of society and politics.

New York Times columnist David Brooks, perhaps the mainstream media’s deepest thinker, wrote this week about the requirements of democratic citizenship, saying “The demands of democracy are clear—the elevation and transformation of your very self. If you are not transformed, you are just skating by.”

Through inner passivity, we find ourselves unable to stand up to (or represent ourselves effectively against) our inner critic, which is a primitive, authoritarian aspect of our psyche that harasses us, puts us on the defensive, and curtails inner freedom. We’re less conscious as human beings when we haven’t exposed this inner conflict and made efforts to resolve it.

Democracy is sustained by the higher consciousness of a significant percentage of a population. When people are less conscious, they’re unwittingly content to be ruled, rather than to cherish the integrity and satisfaction of being capable of being one’s own ruler, meaning in particular the ability to self-regulate, avoid negative states of mind, and fulfill relationship and civic responsibilities.

Even more so, people who are unaware and unevolved are willing, unconsciously, to live according to an inner template, which is to resonate with oneself and know oneself through the passivity inherent in their subordinate relationship with their inner critic. Hence, being ruled politically by authoritarians, rather than being one’s own ruler, feels like the natural order.

It is natural to have deposits of inner passivity in our psyche. We grew up engulfed in passivity. As children, we were dependent on our parents or guardians and at their mercy. A child’s passive experiences include submission to rules and requirements involving toilet training and other socializations. Up to and including teenage years, a young person is held accountable, usually appropriately so, to the authority of parents and other adults. This passivity lingers in the adult psyche, and it creates a largely unconscious emotional veneer that we unwittingly apply to various daily experiences. Much of our sense of victimhood or failure, as well as our passive-aggressive tendencies, anger, and self-sabotage, are byproducts of this underlying passivity.