Ken Lizzi's Blog, page 48

June 6, 2021

Heroic Visions. Warning: Contents May Not Be As Advertised On Cover.

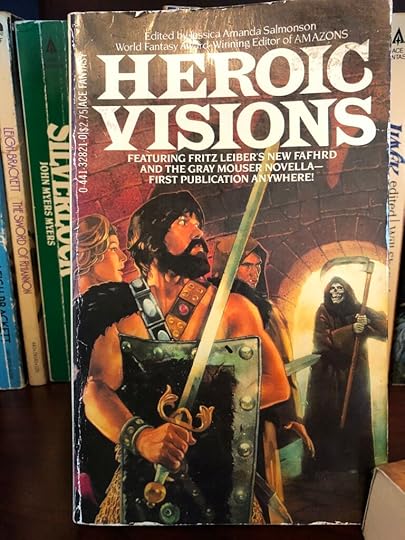

Heroic Visions. Nice title. And take a look at that cover. No, really, we’re going to come back to that. Take a good look. Okay, moving on to the Introduction: The editor, Jessica Amanda Salmonson, seems embarrassed to be doing this, as if editing an anthology of heroic fantasy was more a paycheck than a labor of love, and she wants you to know she is above such trash. In fact, she’s damn well going to do something about it, you Philistine, you knuckle-dragging S&S fan. I think I will avoid engaging with the introduction (from 1983, though rather au courant in content.) Let me merely state that I do not concur. But, to provide an example of JAS’s thinking, I’ll quote part of a paragraph.

Before I do, an aside.There are many other assertions made within the intro, to which I object, but I’m not writing these web log posts to be disagreeable. I think I’ve demonstrated that primarily I write these anthology reviews to celebrate Swords-and-Sorcery, not demean it. I’ll be up front, I’m not going to enjoy writing this post. For the most part, I have no objection to the stories printed in Heroic Visions on their own individual merits. Most are quite good. But, as we go along, take the occasional look at that cover. Consider the title, Heroic Visions. Heroic. Thus endeth the aside, and here follows the quote from the introduction. Consider it as a representative example of JAS’s tastes and opinions, and reach your own conclusion.

“Heroic fantasy, in recent decades, has seemed to be epitomized by Robert E. Howard’s Conan the Barbarian, and this is a sad state of affairs. The millennia-old heritage of magical and heroic tales does not begin or culminate in the rather simplistic fictions of the pulp era or the current, slavish imitations thereof. Howard’s work is admirable; he was surprisingly well read, and invested his stories with the hodge-podge of an amature historian or Harold Lamb fan, creating something primal, evocative, intriguing. Stylistically, he was weak.” [The damning with faint praise continues for a few more sentences.]

So, what sort of stories does JAS think are properly heroic visions, suitable for more refined tastes? Let’s find out, shall we.

The Curse of the Smalls and the Stars. Fritz Leiber. A surprisingly solid first selection. One of the grand masters himself. This story is part of the final Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser collection, The Knight and Knave of Swords. But this choice does represent a bit of a head fake. Leiber has, at this point, taken the Duo in a different direction. This is not the place to consider his reasons, that his own ruminations on age or personal mortality, etc. might have steered his interests onto a new path. Reviewing the story qua story, I can say it is a lesser — and slow paced — tale of the Twain, while still retaining enough of the Leiber touch to render the experience a leisurely pleasure rather than a trudge. Unfortunately, that glacial pace detracts from the forward driving momentum I prefer in S&S and related heroic fiction. The Twain are, in fact, generally pawns in this story, not fully in charge of their own actions. This deprivation of agency undermines the heroism of the characters at a fundamental level. Instead of a heroic visions, this is more of a mediation on maturity and decline. And, to ensure I’m addressing story issues rather than personal preferences — I must note that the motivating incident goes unresolved. The story lacks a narratively satisfying ending. I’ll have to check my copy of Knight and Knave to see if Leiber addresses this in one of the subsequent stories.

Sister Light, Sister Dark, Jane Yolen. There is the backbone of a solid S&S story here. The premise is weird and interesting — the temporarily corporeal and partially independent shadow self as battle companion — and in general the story is entertainingly told without excessive padding. But the framing devices are authorial self-indulgence, and the bald-faced gender politics therein are unnecessary and off-putting. Still, despite the drawbacks, a decent yarn.

Tales Told to a Toymaker. Phyllis Ann Karr. A fine, vintage 80s fantasy tale. PAK displays deft world-building skills and precise control of language. The device of a traveler telling an old friend anecdotes of his adventures works well enough; imagine one of your less reliable Veteran buddies spinning “No shit, there I was” tales. All that said, there is no story here, and what there is ain’t S&S. Heroic fantasy? Perhaps as a courtesy. After all, I did enjoy reading it.

Prophecy of the Dragon. Charles E. Karpuk. This is an atmospheric work, evocative of the Far East. It is a sequence of gorgeous watercolors, picking out details that tell the story while perfectly maintaining the mood and setting. An admirable piece. Alas, not an entertaining one. I do credit the two main characters with bravery. This is indeed a heroic vision, but it isn’t one that engrosses me. Shame. Perhaps in a differently themed anthology it would work better; providing the proper surrounding for the artwork seems an appropriate consideration for this particular story.

Before the Seas Came. F.M. Busby. Another tale with a Far East setting. A promising beginning, trailing off into disappointment. This is partly due, I think to the detachment necessary to the third-person omniscient, stylized “story teller” voice Busby employs. Partly also due to forcing an agenda onto the story. Sometimes doing so weakens the willing suspension of disbelief. I think a more straightforward tale — sans gender politics and absent fluttering virtue flags — would have worked better. But, this is the story he wanted to tell, and I don’t want to be too critical of an artist expressing himself. The story is — fine. It had its highlights near the end; heroic enough. This is one of those stories told in synopses, sections reading like chapter outlines for a larger work. I think this might have worked better as a novel.

Thunder Mother. Alan Dean Foster. Leave it to an old pro like Foster to deliver the goods. I’ve never considered him a practitioner of S&S, but this quasi-historical heroic fantasy compares well to some of the examples found in 60s and 70s anthologies. How did a throwback like this slip through JAS’s filter? The ‘weird tale’ ancestry shines through in this story of Incas, Conquistadors, and ancient magic. Short and sweet.

Dancers in the Time-Flux. Robert Sliverberg. Silverberg contributes a scintillating, novel science fiction story. I suppose JAS figured that if Robert Silverberg writes a story for you, you just accept it, even if he’d mailed it to the wrong editor and sent the one intended for a heroic fantasy collection to, say Asimov’s. This tale is, indeed, a vision. And there are suggestions of heroism of a sort about it. In some respects, this is the most entertaining piece in the book. As to why it is in the book, I remain uncertain.

Sword Blades and Poppy Seed. Joanna Russ. I’m sure this mannered paean to women writers of the nineteenth century is brilliant. But what is it doing in an anthology with this cover? (Go ahead, take another gander at that barbarian warrior, cowled thief, and Death waiting menacingly in the background.) I’ve long since realized that I’ve been conned by the old bait-and-switch, but really now. There are limits.

The Nun and the Demon. Grania Davis. I wanted to like this more than I ultimately did. The payoff of combat against a supernatural foe and the quasi-ironic tragic/horror story ending wasn’t quite worth the slog to get there. Trimming the lengthy first act would have helped. Adding in a Hong Kong style martial arts training scene might have livened it up and added a touch of verisimilitude (if verisimilitude is the appropriate word in this context) to the fight of a slender, untrained girl against a powerful demon. Still, by the standards set by most stories in this book, this is a reasonably heroic vision. Sorry, I really don’t want to be this negative.

Vovko. Gordon Derevanchuk. How did this get in here? Action/adventure S&S riffing on Slavic legend. Skin changers, water demons, a monstrous child, magic, a descent into the underworld. And, did I mention action? Finally, a story that seems to belong beneath the cover of this book. A bit late, if you ask me. Only one story left.

The Monkey’s Bride. Michael Bishop. And, we’re back, after that brief hiccup of a genuine piece of heroic fiction. Just to remind you what JAS thinks of the field, here’s an excerpt from her intro to Michael Bishop: “In a field — a genre if you will — more and more dominated by writers whose styles are more suited to comic book scripting or exploitation film screenplays, MIchael Bishop is a rarity indeed.” I’ll leave that right there for you to digest. Moving on The Monkey’s Bride: A well written, moderately humorous piece of fantasy/magical realism, with a deliberately ambiguous — though suggestive ending. Fittingly, there is nary a hint of heroic fantasy about the ultimate story. Got a few chuckles out of it, so there’s that.

Summing up: I’m okay with things not being for me. But please, be up front about the nature of the work. Don’t provide a suggestive title such as “Heroic Visions” and slap a colorful S&S cover promising action and supernatural antagonists onto a book whose very mission is to thumb its nose at those of us who enjoy such material. I want to reiterate that I genuinely enjoyed most of the stories in this anthology. But, and this is important, CONTEXT MATTERS. I don’t like to be duped. I spent money on a book I wouldn’t otherwise have purchased. So, good job Ace’s marketing department, I guess.

Now I’m too grumpy to promote my own work. Grrr. See you next week.

May 30, 2021

The Swordbearer. Elric? Turin? Not Quite.

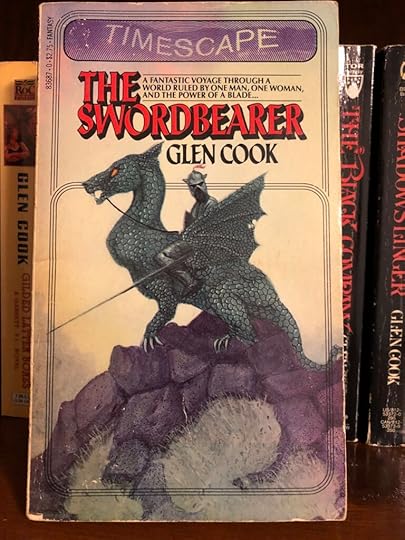

Glen Cook’s bibliography indicates he’s been publishing fiction since the early 1970s. So 1982’s The Swordbearer shows the work of a writer with a good decade of craft under his belt. Ten years isn’t really that long in the scribbling biz, but even at this early stage in his career, some of the stylistic quirks of Cook are apparent: the naming conventions, the fast pace, the glossing over of detail, and the complex interlocking of backstabbers that makes figuring out who shot Nice Guy Eddie seem child’s play.

Anyway, Swordbearer is relatively early Cook, but nonetheless solid. How to pigeonhole the genre? Tough. A synopsis would suggest that there are enough quests, continent spanning wars, battles, and deep time backstory to easily qualify Swordbearer as epic fantasy. But the book isn’t even 240 pages long. It is told with Cook’s typical economy, sometimes reading more like Sword and Sorcery, even though the opening chapters suggest more of a YA, coming of age tale.

As usual with Cook, the characters are almost all morally complex. If Cook were a digital photographer, he’d be baffled by the chromatic spectrum, working only in grayscale. Even the big bad emperor assaulting the West is, ultimately, a sympathetic character. Some of the foul, murderous, nigh-immortal beings are portrayed as possibly redeemable, their actions understandable. But don’t trust any of the characters in Swordbearer. Keep spinning in a tight circle, because if you ever come to a stop, you’ll find a knife between your shoulderblades.

Sounds a bit like The Black Company, doesn’t it?

The hero of the tale is a likeable kid, forced to grow up fast, and selected/compelled to take up a cursed sword. A sword that has an evil will of its own. Swordbearer is fundamentally a tragedy, going over ground you’re already familiar with if you’ve read the doings of Elric and Stormblade and/or Túrin Turambar and Gurthang. But for fans of S&S, familiar ground isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

If I had to summarize Swordbearer, I’d call it preliminary concept work for The Black Company, combined with Michael Moorcock’s Stormbringer and Mournblade, along with a special guest appearance from Tolkien’s Nazgul. I’m an admitted fan of Cook, so take this recommendation for what it’s worth: pick up a copy of The Swordbearer, crack open a beer, enjoy.

If you’re looking for something newer, how about my Falchion’s Company Series? Book one, book two, book three.

May 23, 2021

Mamelukes. A Conclusion?

It almost feels as if a gap in my life has been filled. The saga of Rick Galloway and his mercenaries, whisked away by a flying saucer from a hilltop in Africa just before being overrun by Cubans, is complete at last. Maybe, anyways.

I’ve been reading the Janissaries books since I was a teen. Unfortunately, after publication of the third book, Storms of Victory, in 1987 (the year I graduated highschool), the series appeared defunct, ending on, if not a cliffhanger, at least with uncertainty. Once nigh instantaneous access to information came along, some years later, I began to check every now and then for rumors of another volume. When I learned that Jerry Pournelle was working on it, I was happy. I seem to recall even reading a few pages at his website of the work in progress. But, alas, years continued to pass. And then, tragically, he went the way of all flesh. I thought that was it.

I was very pleased to learn that David Weber, and Jerry Pournelle’s son, had completed the book. Having waited so long, I was willing to stick it out longer for the paperback, so it would fit better with the first three books. (OCD? Maybe.)

Perhaps I could have dragged out the reading of it, savoring the experience longer, but I tore through it nearly as fast as I would have as a younger man with fewer responsibilities. Now I’ve finished, and I have a few thoughts.

I liked it. It can serve as a conclusion to the series. The plot is far from wrapped up, but the book ended with an indication of how the surviving characters might proceed. I’d like more, of course. Ideally I’d be able to read how Pournelle intended to resolve the issues involving galactic politics. I’d learn if Rick ever managed a quiet retirement with Tylara. Who ends up running the show on Tran. What happens to Gwen and Les. Etc., etc. But, we learned enough that I can make some guesses. All at the end of a massive battle that occupied about the last two hundred pages.

Bringing me to another point. The hand of David Weber is clear. None of the first three books exceeded 383 pages (and those were illustrated.) Mamelukes weighs in at 822 pages. Lengthy battle planning sessions and exacting descriptions of the mechanics of sailing suggest the influence of Weber’s exhaustive style. I’m fine with it. All interesting stuff, and well done. Never dull. But I couldn’t help but wish for an alternate future in which Pournelle had been able to take those 800+ pages and produce two books, carrying the story farther.

We meet new characters. In the book chronology, at the commencement of events, it has been thirteen years since Galloway left earth. So it is interesting to introduce characters who experienced the eighties and early nineties. What are laptops? We are introduced to a highschool professor, an ex-soldier, and an ex-SF policewoman. (The policewoman is one of the plot threads left dangling at the end. Was she plotting something? Was she an agent of an alien faction?) And we meet the leaders of a British Gurkha unit, bringing along a welcome complement of 60 deadly Gurkhas.

I noted in an earlier post on Janissaries, that I believed Rick’s mercs were armed with H&K battle rifles. In the later books I raised an eyebrow on reading mention of M-16s. Mamelukes clears it up by mentioning that they were primarily armed with H&Ks, along with a few M-16s. Good enough. The Ghurkas bring the British variant of the FN FAL. They also bring along one of the bits of news that seems to shock Galloway’s men as much as word of the fall of the Soviet Union: that the US Army adopted the 9mm Beretta in place of the .45. I chuckled at that.

Will there be more? Messrs. Pournelle and Webber leave the door open for continuing the series. If they do, I’ll certainly check out the first. If not, I’m content. My imagination has been provided enough information to devise a satisfactory fate for Rick Gallowy, et al.

Ave, Galloway.

May 16, 2021

Six-Guns, Blasters, and Broadswords: The Western and Speculative Fiction

Reading a collection of Louis L’Amour stories has got me thinking about the Western. The Western genre has generated a solid collection of tropes and narrative expectations. It also, it seems, has exercised an influence on science fiction and fantasy; that is, certain speculative fiction stories traffic in the same tropes. All to the good, in my opinion.

I suppose I ought to dip a toe into what makes up a Western, before I proceed. This is a mere surface grazing. Attempting a precise definition of the Western is limiting. Why try to corral a genre with vast possibilities?

A common Western plot is A Stranger Comes to Town. This stranger will uncover a mystery, right a wrong, then move on. The wrongs involved are often a corrupt powerbase in the (usually small) town; an attempt by a powerful landowner to illicitly acquire the land of a less powerful landowner (a cattle ranch, a farm, a plot by a future rail lane, a mine claim, etc.); a powerful man attempting to steal away a woman from a less powerful man. There are often considerations of the decadent east encountering the rough virtues of the primal but pure west. The march of progress pushing back a savage frontier. There might be elements involving the danger of expanding into new territory or merely the difficulties involved in travel (weather, distance from resources, hostile natives — previous inhabitants disgruntled at being forced off.)

Why might any of these be attractive to the writer of speculative fiction? Well, consider the Stranger Comes to Town. The stranger is your POV character. He knows nothing of local conditions and must learn them. This sort of doling out of necessary plot information avoids the As You Know, Bob exposition problem. The writer of fantasy and science fiction must ladle out background that isn’t common currency to the reader, explaining the secondary world, the magic, or aliens, or new technology. The Western also offers a familiar template for a short story, the drifter is going to come to town, then leave town: there is a built in limitation that keeps a story from feeling artificially truncated; the reader isn’t necessarily left wondering what else is occurring in this new world since the expectation of the end is baked in.

Of course it isn’t exactly cut and paste. There is more involved than simply taking the plot of a Western and replacing the six shooters with broadwords or blasters, exchanging the Iron Horse for a spaceship or passenger dragons. But the model is solid.

Consider C.L. Moore’s Northwest Smith stories. Moore’s Mars and Venus are the Frontier. NW is the drifter (though not always a lone drifter; his Venusian partner in crime, Yarol, is a frequent sidekick.) Ancient, weary Martians and Venusians can stand in for Apaches and Sioux.

What about Conan? A Texan like Robert E. Howard, who also wrote Westerns, might be expected to use the same model for his Sword and Sorcery. Well, Beyond the Black River springs immediately to mind. But that is really more a Frontier story; James Fennimore Cooper rather than Max Brand. Shadow in Zamboula might be a better example: Conan comes to town, deals with a mystery (a sinister innkeeper), savages, and is instrumental in a power struggle between two powerful factions, before drifting on.

The Western can also work in longer form fiction. Joe Abercrombie’s Red Country might as well have slapped a Louis L’Amour cover on. It is an unapologetic Western, checking all the boxes, from native tribes (red-heads, I seem to recall), the impending drive of progress (steam engines), rival powers in a frontier town (right out of A Fistfull of Dollars), and more. Mike Resnick’s Santiago: A Myth of the Far Future serves as a similar example in science fiction.

So, next time you are reading through — for example — a collection of Sword and Sorcery tales, you might take a moment to consider what the story would be like if set in Dry Gulch or Tombstone. There are other genres that mesh well with speculative fiction: the detective story, for one. I’ve done that, as well as blending the crime and fantasy genres. Why not give them a read, let me know what you think.

In any case, happy trails, partner.

May 9, 2021

Mother’s Day 2021

Stand and doff your caps to mothers. They deserve it. Good, bad, or indifferent, they gave us life, and that’s an unpayable debt. So don’t feel guilty about merely sending a card; there’s nothing expensive enough you could give to recompense your mother for your existence, unless you value yourself lightly. (Don’t do that.)

In honor of Mother’s Day, let’s consider a few fictional mothers.

How about Conan’s mother? Giving birth on a battlefield is hardcore. One has to assume that at least some of Conan’s toughness, grit, and determination came from the distaff side.

Tarzan, also, seemed to have inherited admirable qualities from his mother, Alice Clayton. It would, perhaps, be too much to ask for her to have withstood the ape attack on top of all the rest of the calamities she’d endured. So, while his mental toughness likely came from John, at least a measure of his bravery and loyalty can be attributed to his mother.

What about Lady Jessica, Paul Atreides’ mother? I wonder if there is a more influential mother of a main character in speculative fiction. Think about it: she violated a direct order from the Bene Gesserit to conceive a daughter. And that’s just the first of her influences.

The truth is, we don’t get much — or any — information on the mothers of most fictional characters in the sort of adventure-driven fiction I like to read. That’s perfectly understandable, we want to get on with the story. As writers, many of us — in Elmore Leonard’s words — leave out the parts people tend to skip. Detailed backstory is generally one of those things excised or never written in the first place. So note those mothers who do get mentioned. Those mothers probably had some influence in the development of the characters, and it can be interesting to spot it.

While on the subject of Mother’s Day, if your mom likes to read genre fiction, perhaps you might send her something of mine.

May 2, 2021

Fantasy’s Big Three

Science Fiction has its big three. Most often these are listed as Asimov, Heinlein, and Clarke. The line up varies, of course. It can’t be objectively determined and prominence waxes and wanes with time. Weird Tales had its own holy trinity: Lovecraft, Howard, and Smith. Three seems to be a magic number. Who, I wonder, would be Fantasy’s big three?

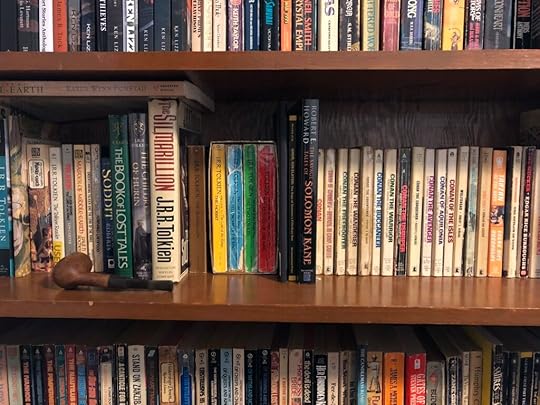

The question at first seems readily answerable, since the first name springs instantly to mind: J.R.R. Tolkein. It isn’t merely that The Lord of the Rings is influential (that’s undeniable.) It is that Tolkein sells consistently. LOTR occupies valuable real estate in every book store. It never goes out of print and new editions spring up frequently.

So, easy, right? One down. How hard could it be to pick two more?

Yeah.

This isn’t a question of who was/is influential. This is a question of popularity, longevity, and book spines cracked in the Fantasy genre writ large, no drilling down to subgenres. I could look to an easy way out, conjuring by the name of J.K. Rowling. Talk about sales, there’s your gal. But Harry Potter is children’s fiction. So, sadly for my lazy ass, I have to disqualify the series. Same goes for C.S. Lewis, an Inkling with a solid track record. Ursula Le Guin deserves some consideration. But I re-read the Earthsea Cycle a couple of years ago, and I have to consider it to fall in the same category as Harry Potter and The Chronicles of Narnia. Besides, Le Guin is better known for her Science Fiction.

I keep coming back to Robert E. Howard. Conan, since his renaissance, has enjoyed Tolkein level sales, name recognition, and shelf space. Plus, Howard spun tales of numerous other well-known characters and they all take up room in multiple collections. Gradually becoming part of the public domain has done nothing to slow the popularity of Howard’s fiction; quite the reverse.

So, that’s two. Excellent. Almost done. I can do this.

What have we got? Glen Cook is considered by some the progenitor of Grimdark. He is influential among other writers in the field. But, that isn’t quite what I’m considering here, is it? I’m more concerned with the larger reading public than we scribblers of fiction. (Yes, I’m including myself. And yes, I fully realize what an almost microscopically small fish I am in this pond.) So, despite providing some impetus to Erikson, Abercrombie, Morgan, et al, and despite my personal appreciation for his output, Cook is not the third leg of the stool.

What about Edgar Rice Burroughs? I can’t quite bring myself to classify Tarzan as Fantasy, though I am certainly sympathetic to the argument and wouldn’t expend much effort disputing you if you disagree. John Carter is Sword and Planet. Now, I’m willing to consider that a branch of Sword and Sorcery, and thus Fantasy. But I’m not sold on Barsoom books fighting in the same weight category as LOTR and Conan. Besides, if we are including Sword and Planet, I’d want to consider Anne Mcaffrey and her Dragonriders of Pern books. I don’t have any statistics immediately at hand, but my memory suggests that those books occupied more square footage in the bookstores than John Carter of Virginia. (I could be wrong. There’s nothing of the scientific method involved in this post.)

It may be that the third member of the triumvirate is the scribe of one of the massive door-stopper series. Robert Jordan, say, of the seemingly interminable Wheel of Time. Or G.R.R. Martin of the perhaps actually interminable A Song of Ice and Fire. Both men had prior success. Both, whether from sheer mass, popularity, or both, continue to move product. This, I think, remains open. Will either series achieve the long term success of Tolkein’s or Howard’s output?

The same question applies to some of the more recent successes, like Jim Butcher or Larry Correia. Will future generations continue to care about Butcher’s Harry Dresden or Correia’s monster killers? To be seen.

I’d like to say Zelazny. Shoot, I’d like to say Vance. Talk about influential. There are several that I’d be happy to say carry the same stature with the general Fantasy reading public as Tolkien and Howard: Lord Dunsany, Saberhagen, De Camp, Pratt, Leiber, etc. I have a long list. Moorcock ought to be given consideration. Elric is the great granddaddy of any number of brooding, emo swordslingers. But I fear he might be a trifle niche to make the cut.

I suppose the answer I come up with is that there isn’t a Fantasy big three. Instead, Fantasy boasts a duo. But I’m open to persuasion. What do you think? Am I missing someone obvious? Should Terry Pratchett get the nod? Tell me what you come up with.

To help grease your mental gears, how about some reading?

April 25, 2021

The Once and Future King. Now and Forever a Classic.

There is a certain freedom attendant to writing about The Once and Future King with the knowledge that I cannot possibly do it justice. I can write without the pressure to reach an unattainable goal. Now, if young Wart — Arthur — had commenced with such foreknowledge of inevitable failure, he’d never have bothered tugging the sword from the stone.

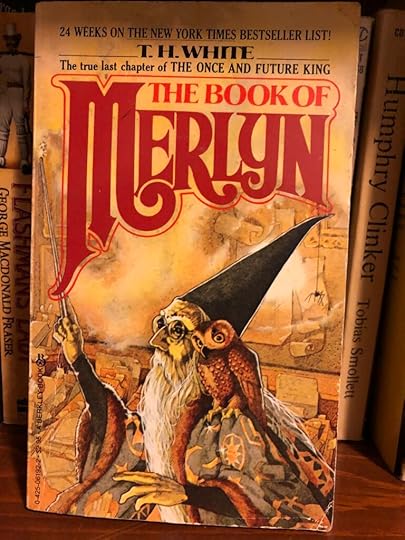

It has taken me longer than you might expect to finish reading this book. Sure, it is hefty enough, but I’ve zipped through longer works in fractions of the time I spent on this. Why so slowly, then? I read this with deliberate lack of haste, savoring each section, not wanting to get to the end. The story and the quality of the writing, the subtleties and careful choice of words are just that good. And, anyway, why would I want to reach the well-known tragic conclusion? It’s tragic. I’m eager to move on to The Book of Merlyn now, White’s follow up.

T.H. White’s masterpiece is one of the three great humane fantasies, along with Watership Down and the Lord of the Rings. Watership Down is (perhaps oddly, considering it is a novel about rabbits) itself the most humane of the three. The Lord of the Rings is the most transcendent. But Once and Future is the most human.

The novel concerns itself with the individual in all aspects of life, from childhood to old age and does so with humor, compassion, and unflinching reflection. It also grapples rather grimly with larger questions of society. War, justice, love, friendship, family, the nature of man. Perfectible? Unalterably flawed by original sin? A mechanistic creature evolved to instinctively respond to certain stimuli in certain ways?

Once and Future takes the familiar story of King Arthur, one that underpins much of English literature, and treats it, initially, as a comedy, before gradually sliding into tragedy with liberal lubrication of black humor. It is, in many ways, a despondent work, though it ends with a glimmer of hope as summed up in the final two words: “The Beginning.” Of course that glimmer is right there in the title.

This isn’t the sort of gung-ho adventure novel of the kind that makes up the plurality of my reading. But I want you to note the following passage, which suggest to me that White had the chops to take the story in an entirely different direction, had he so chosen:

“…and a single knight in full armour blundered through the gap…Lancelot slammed the door behind him, shot the bar, took the figure’s sword by the pommel in his padded left hand, jerked him forward, tripped him up, bashed him on the head with the stool as he was falling, and was sitting on his chest in a trice — as limber as he had ever been. All was done with what seemed to be ease and leisure, as if it were the armed man who was powerless. The great turret of a fellow, who had entered in the height and breadth of armour…he seemed to have come in, and to have handed his sword to Lancelot, and to have thrown himself upon the ground. Now the iron hulk lay…while the bare-legged man pressed its own swordpoint through the ventail of the visor. It made a few protesting shudders, as he pressed down with both hands on the pommel of the sword.”

See what I mean? You could almost replace “Lancelot” with “Conan.”

It surprises me that it wasn’t until after I rounded fifty and began my steady pace toward the century mark (and beyond? Fingers crossed.) that I finally got around to Once and Future. But perhaps that was for the best. I might not have gleaned as much from it as a younger man.

Recommended. Now, if you’re in the mood for something more along the lines of a gung-ho adventure novel, why not this one?

April 18, 2021

The To Be Read Pile: A Love-Hate Relationship. (Mostly Love.)

We all have one, constantly growing or shrinking. A heap of books; the to-be-read pile. (What did you think I was writing about?)

Mine expanded a bit in Florida. We stopped at a thrift store on the way to the airport. I wanted something to read while waiting for the plane. I grabbed three paperbacks to get the three for two dollars deal. I’m nearly done with a J.G. Ballard collection, Passport to Eternity. But waiting to be read are the other two, contributing to the TBR pile.

One is Bowdrie, from Louis L’Amour. You can never go wrong with L’Amour. If you’re in a hurry, uncertain what to buy, just grab one of his westerns. You’ll be entertained. The second is Pale Gray for Guilt. John D. MacDonald was an absolute master craftsman. I’ve read a few of the Travis McGee novels. But I’ve never truly warmed to them, and so I don’t go out of my way to track them down. MacDonald’s mouthpiece McGee has a way of preaching to the audience that I find off putting. All the great ones did it to some extent: Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, even Archie Goodwin. But their authors were more restrained. McGee’s bad mouthing the United States of America (to borrow a phrase) can stick in my craw and undermine my appreciation of the story. And that’s a shame, because MacDonald can damn well tell a story. Fingers crossed on this one. Maybe he was in a better mood when he wrote Pale Gray.

I am nearly done with T.H. White’s The Once and Future King. Which means I can finally get to a book I’ve had sitting on a bookshelf for I don’t know how many years. I haven’t read The Book of Merlyn because it is supposed to be a sequel to Once and Future, and I’d never read it. I’m looking forward to it.

Continuing the renewed King Arthur kick I seem to be experiencing, why not add Steinbeck?

I have little familiarity with David Gemmell. I read Legend years ago, a sort of Alamo meets Minas Tirith novel and liked it, despite what I considered a few weak spots. I believe that was his first novel. I’m curious to see if Dark Moon is more polished, while still retaining that adventurous heart.

Glen Cook’s output dominates most of one shelf in bookcases. I re-read the Black Company series what, last year? Only the extent of the TBR pile is preventing me from wallowing about in the Garrett Files series again. (I’m tempted to do it anyway. Garrett is the closest thing I have to a fictional hero. And Cook almost unerringly nails the detective literature mashup and seamlessly integrates his portmanteau investigator into a fantasy milieu. It is a world I love to revisit.) How could I resist picking up The Swordbearer?

What is on your TBR pile? Has it taken over a substantial portion of your domicile? If not, why not add to it?

April 11, 2021

The Year’s Best Fantasy 1975. The Question Mark is Presumed.

I picked up a collection of what composed the pinnacle of fantasy short stories in 1975, the unapologetically titled The Year’s Best Fantasy. A bold claim. True or not, these pieces are, at any rate, what the editor of the anthology considered the best. The editor? Lin Carter, whose objectivity and disinterested, selfless focus on the fulfillment of his task we’ll come to appreciate in this post.

I’d like to start by sincerely noting a classy act of Carter’s right out of the gate. The book is dedicated to Hans Stefan Santesson, who had recently passed on to whatever mead hall sword-and-sorcery editors ascend to. I covered one of his books, The Mighty Swordsmen, in a previous post.

Lin Carer’s introduction notes the passing of J.R.R. Tolkein. It is an interesting snapshot of the Professor’s import and reputation in the early 1970s. Carter’s paragraph on Conan reads as rather disingenuously self-serving (take note) and his paragraph on Ballantine’s retirement of the Adult Fantasy Series carries the whiff of sour grapes. But who can blame him? I don’t. Watership Down gets Carter’s passive aggressive dismissal, for which I might blame him if I hadn’t come to the realization at some point in my first half-century that tastes differ. The estranged, herky jerky career of Weird Tales gets an update. The introduction is interesting primarily for two aspects:one, the comparative paucity (compared to today, that is) of fantasy offerings in the market; and two, the impressive number of plugs for his own disparately published work Carter manages to worm into his intro for his new editorial gig. (I’m sensing a trend.)

The Jewel of Arwen. Marion Zimmer Bradley. We start off with fanfic. Hardly promising. Carter could not have known — or so I presume — that Bradley’s offering would be a ticklish proposition here in the first quarter of the 21st Century. That is, one cannot, in 2021, write about Marion Zimmer Bradley without addressing the MZB stench in the room. I have read some MZB. Not much though. I recall reading The Mists of Avalon when I was 12. To me it seemed an odd exercise, writing an Arthurian mythos novel while excising all the exciting parts. But I was stubborn, even then, and powered through. Two or three years later I submitted one of my earliest attempts at fiction to Marion Zimmer Bradley’s Fantasy Magazine, receiving a nice rejection letter that mentioned something about humor being subjective. (I’ve since lost that letter, probably during one of my many moves.) I’ve read the odd story or novel of hers here and there over the years, none of which left a strong impression. The point is, while her work has never really been to my taste, the connotations her name held for me were not entirely negative. But now…well, while I’m generally of a mind to separate art from artist, MZB makes that a challenge. I’ll give it the old college try, however. The Jewel of Arwen is LOTR fan fiction. MZB is a competent mimic. The prose is…adequate. It evokes, but can’t truly match, JRR’s magisterial tone. And it feels empty. It purports to trace the prior ownership of the white gem Arwen gives to Frodo. That it does, and that’s about it. Any depth in the piece is, to my mind, illusory. So I wouldn’t say it is a poor story, but I don’t see a point to it. If this was one of the best stories of the year, then the crop must have been poor.

The Sword of Drynwyn. Lloyd Alexander. Alexander pens a Pyrdain tale. (I don’t have to explain Prrdain to this readership, do I?) There is something of the Greek tragedy about this. It is the sort of plot Shakespeare might have cribbed for one of his plays. It tells of villainy and cowardice snowballing from a single failure to recall making a promise, leading to the downfall of an otherwise honorable — perhaps — king. Good. Compact. Appropriately stylized. I recommend it. Certainly a step up.

The Temple of Abomination. Robert E. Howard (as completed by Richard L. Tierney.) A Cormac Mac Art story, one adverting to Arthurian myths. (King Arthur is a recurrent the in my reading this year. It’s like the guy is following me, it’s creepy.) Temple is a short dungeon crawl, told with Howard’s characteristic verve and gift for mayhem. Slight, but entertaining. Tierney (chronicler of Simon of Gitta) rather seamlessly brings this vignette, this seeming chapter of a larger work, to a proper semblance of an ending. REH always classes up a party.

The Double Tower. Clark Ashton Smith (with an assist from Lin Carter.) The second of two old partial works considered eligible due to later revision/completion. This is a short short, a fragment or outline fleshed out and completed by Carter. Carter again proves himself an able literary impressionist. As you might expect from CAS, this is a tale of a hubristic mage hoisting himself ironically by his own petard. Carter provides a convincing facsimile of Smith’s gorgeous, baroque style. I liked it. REH followed by CAS. Things are looking up.

Trapped in the Shadowlands. Fritz Leiber. Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser. Enough said, but if you require more, I briefly reviewed this one here.

Black Hawk of Valharth. Lin Carter. Well, I suppose if you’re tasked to select the best stories of the year, there’s no law against tapping one of your own for the honor. Still, there is an attendant odor to the practice. That aside, is it any good? Verdict: It is…competent. Thongor’s original story, somewhat stereotypically premised upon vengeance for his slain clan. There is little originality, and not much of the color and imagination that power the better Thongor tales. And I do have questions about certain aspects of the narrative, but asking them would be overthinking a story I don’t believe Carter gave a great deal of thought to himself. Enough. I don’t care to be harsh. Even Homer nods.

Jewel Quest. Hannes Bok. Bok tries his hand at the libretto for a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta. This reads as a burlesque of the Oriental Tale. It is slight, the jokes rather weak and dependent on rather childish mockery of eastern languages. It wouldn’t stand a prayer of publication today. But, Philistine that I am, I found it moderately amusting. Another tale of well-deserved comeuppance.

The Emperor’s Fan. L. Sprague de Camp. Another fantasy of the Far East. But, as one might expect from de Camp, this one is a clear step above Bok’s trifle, as if de Camp said, “Hold my beer, Bok. This is how you do it.” De Camp brings his characteristic drollery and borderline misanthropy — or, at least jaded view of humanity and skepticism concerning inherent virtue. Also, as usual, his tendency to dwell on the nuts and bolts of his invented magical machinery is evident. He gave it careful thought and he wants you to see his work. Still, as it plays a role in the plot (multiple comeuppances) it hardly detracts from the fun.

Falcon’s Mate. Pat McIntosh. One of those titles with double meanings, if you care to garner them from the story. I rewrote this commentary, since my first one was unduly harsh. Who, after all, am I to be overly critical? This is a first person account of a member of a selective order of women warriors escorting an unwilling bride to her marriage, and some sort of shapeshifting magician, all of it mediated through an ill-defined, chess-like game and set in a lightly sketched out fantasy world. Maybe this is a story for you. It didn’t work for me. Still, setting aside personal preferences, was it truly one of the best of the year? I suppose Carter thought so. What do you think, reader?

The City of Madness. Charles Saunders. According to the intro to this piece, this was his first published story. Impressive, if true. One of the pleasures of devouring so many fantasy anthologies recently was the opportunity to read Saunders. The Imaro tales are the real deal. It isn’t, in fact, a tremendous surprise if this was his first published Imaro story. There are a few rough spots, and I don’t think Saunders fully stuck the landing. But this is a vibrant, visceral story that hits all the right S&S notes. (REH, CAS, Leiber, de Camp, and now Saunders. Despite my kvetching, there’s some good stuff in here.)

The Seventeen Virgins. Jack Vance. I grinned with anticipation the moment I read the name Jack Vance. And it’s a Cugel the Clever story (so I presumed from the start that the number 17 was unlikely to remain accurate by the end of the story.) Cugel makes it worth the price of admission to the vaudeville show, even if the other acts stank (which they did not, despite the MC hogging much of the spotlight.) Cugel, much like Flashman, is a bad man. And, again as with Flashman) I chuckled nigh constantly at each act of villainy. (If that makes me a bad man, so be it. At least I’m happy.)

Bonus. Note the Appendix, in which Carter lists the best original fiction books of the year, in which he manages to include not merely one, but two of his own. Is there a touch of Cugel about Carter? I will suggest that Carter took full advantage of all the perquisites of his office, unconcerned by any appearance of impropriety. He’s not shy about hawking his own wares.

And so, in honor of Carter, I’ll do the same. I’m anxious to begin marketing my new series, but as the publisher is still wrangling cover art, I’ll have to bide my time. But I do have other books. Perhaps you might fancy a post-apocalyptic/sci-fi/fantasy/action adventure. Got you covered. How about a space going sci-fi tale that serves as an homage to ERB’s John Carter books? Look here. Or, looking for a crime/S&S mashup? Right here. Tired of stand-alone novels; searching for a fantasy series? Look no further than my trio about a mercenary building his own company of sellswords. Book one remains on sale. These are all Amazon links, but, with the exception of the series, all of these should be available wherever you buy books on-line. There, I feel closer to Lin Carter already.

April 4, 2021

Sellswords

I’m waiting for my paperback copy of Mamelukes to arrive, sometime in May, so I can finish reading Jerry Pournelle’s Janissaries series. I began reading these books in the 80s. I think I’ve waited about long enough. Sitting here and waiting I have mercenaries on the mind, given the premise of that series: human mercenaries sent off-planet to fight an alien conflict. (That’s not an entirely novel concept, now that I think about it.)

So, I’m thinking about mercenaries. It seems de rigueur for the barbarian hero to serve as a mercenary at various points in his vagabond, blood-soaked career. And why not? What better way for a writer to get his hero into conflict? Hero needs cash, mercenary army needs strong sword arms. A match made in Valhalla.

Evidence, Ken? Or are you just blowing smoke?

Excellent question, imaginary reader. Consider the granddaddy barbarian, Robert E. Howard’s Conan. How many times did he serve as a mercenary? That would be a fun research project, an excuse to re-read the stories again. (Probably fewer than my memory suggests.) But I wouldn’t make deadline if I did so. So, let’s throw out a single example: Beyond the Black River. Conan isn’t serving as a regular Aquilonian soldier. He’s a hired auxiliary, a sellsword, scouting for pay. And it gets him into the thick of things.

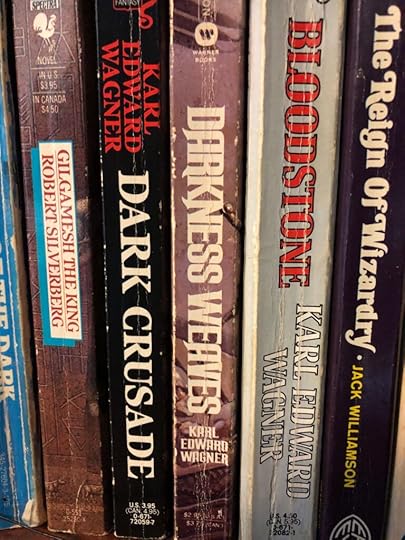

Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane finds mercenary work an excellent way to reach positions of power and manipulate circumstances to what he thinks is his advantage. He’s had plenty of time to learn on the job.

As I recall, certain of Zelazny’s Amberites spent quality time as mercenaries, as well as serving in standing armies. Moorcock’s Elric and Moonglum are often soldiers of fortune. Fletcher Pratt’s The Well of the Unicorn prominently features mercenary companies. The mercenary company is itself the focus of Glen Cook’s The Black Company. And, of course, more recently, companies of sellswords are significant players in George Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire. Ramsey Campbell’s Ryre is a mercenary, though he’s usually in between wars, fighting some supernatural horror or other.

The condottiero and the sellsword are useful narrative figures. No politics need necessarily drive the story. The mercenary isn’t fighting for a country or a cause. The conflict itself is the story, not the reasons for the conflict. There is often a presumed amorality attached to the sellsword, thus there is little need to establish right or wrong between the belligerents, and the author can get directly to the action. Time can be spent on individual qualms or internal disputes, rather than on geo-political or social issues. It’s a good setup for a writer of swords-and-sorcery. I’ve used it myself.

No doubt readers of this web log can think of many more examples. Are there some outstanding examples you can think of? There could well be one I haven’t read yet.