Barbara Gaskell Denvil's Blog, page 14

February 9, 2016

New Releases..The Flame Eater & Between

Having decided to self-publish rather than stay with my previous traditional publisher, I am now delighted to have the freedom to publish any number of books at any time. Whereas traditional publishers limit an author to publishing one book a year – I can be thoroughly irresponsible and publish two together!

And that is precisely what I have done. I am proud to introduce my two new publications, The Flame Eater, and Between.

These two novels are entirely different to each other. The Flame Eater is now my fourth historical novel In accordance with the others, this mystery-crime-adventure-romance is set in the late 15thcentury, the late medieval period which fascinates me and has become the period of my greatest research over the years. I may live in a small and very comfy cottage in the semi-rural beauty of Victoria, Australia. But I spend most of my time in medieval London, exploring the alleys and shadowed buildings, the winding power of the tidal Thames, and the palaces of the high clergy and the nobility. It is definitely my second home. Old London may exist purely in my head, but it is very real.

These two novels are entirely different to each other. The Flame Eater is now my fourth historical novel In accordance with the others, this mystery-crime-adventure-romance is set in the late 15thcentury, the late medieval period which fascinates me and has become the period of my greatest research over the years. I may live in a small and very comfy cottage in the semi-rural beauty of Victoria, Australia. But I spend most of my time in medieval London, exploring the alleys and shadowed buildings, the winding power of the tidal Thames, and the palaces of the high clergy and the nobility. It is definitely my second home. Old London may exist purely in my head, but it is very real.

But inspiration varies for every book, and this one was actually born through the appearance of the hero Nicholas, fully formed in my head. The creation of any fictional character is a slightly strange process. People often ask, “Who is this character based on? Do you write about your friends or neighbours, disguising them under false names? Are all your characters secretly copied from members of your family, even the villains?”

Well – no – none of that. Perhaps some writers do this sort of thing, but frankly it is rare. Fictional characters are invariably born purely from the imagination. Some tiny seed roots itself in your mind and there it glues, takes shape and grows until it is a fully formed personality, quite separate from anyone you have ever known. After all, I make great efforts to present my characters as three-dimensional, but they can never be as multi-dimensional as anyone actually alive.

My initial idea stemmed from wondering how a very strong character might cope with being treated as beneath contempt and unworthy of attention by his arrogant family. Most books present such a man as angry, rude and vengeful, someone who will fight to prove his worth and lose his temper at the injustice of his treatment. Invariably he would be shown as impatient and furious. Authors seem to think such a young man will push and shout in order to vindicate himself.

But the haughty, rude and angry personality of so many books does not correspond to how I have discovered reality. I therefore decided that a character sufficiently strong and confident in spite of his family’s stupidity, would actually use humour as his defence rather than his temper, and would simply laugh at any attempts to undermine him. Thus Nicholas was born in my head, and I fell in love with him at once. He is now one of my favourite heroes, and he is certainly unusual.

At the same time, I learned some interesting and little known historical facts concerning Henry Tudor before his invasion of England, and that enlarged my plot. Then the final inspiration – I became interested in the psychology and injustice of the old system of arranged marriages and how terrible this must have been for young women forced into marriage against their will.

I disagree with much of what I have read over the years, for noble and wealthy women of that time were well accustomed from childhood to the idea of marrying a complete stranger, and for political motives, the dowry system and the need of family alliances. . Of course there were young women pressured into marriage against their wishes – but many were only too eager to marry someone of wealth and importance, who would then facilitate their own entrance into the world and enlarge their lifestyle and title. It is also fair to point out that many young men were pushed into marriage against their will. But most accepted the inevitable since a wedding was an alliance and rarely if ever seen as a romantic attachment. It was usually designed to aid both sides. However, this convoluted range of possibilities began to form itself into an interesting storyline in my mind.

And there it was – The Flame Eater was born.

I love my characters. Nicholas and Emma carry my book to its end, and the romance between them is unusual, unconventional, but – I hope – delightful. Yet there’s more. I don’t write romantic stories without interweaving plots. So here there is medieval history wrapped up in a crime mystery – and the romance weaves through it all.

My other recently published novel Betweencould not be more different. I have never written anything quite like this before –for a start, it is basically contemporary. This is a dramatic crime-mystery – a who-dunnit – no romance this time although there are many interweaving storylines and the plot is by no means straightforward. Mystery is the main ingredient, but this is no fantasy either. In other words – a crime drama with a twist. And it’s a big twist.

My other recently published novel Betweencould not be more different. I have never written anything quite like this before –for a start, it is basically contemporary. This is a dramatic crime-mystery – a who-dunnit – no romance this time although there are many interweaving storylines and the plot is by no means straightforward. Mystery is the main ingredient, but this is no fantasy either. In other words – a crime drama with a twist. And it’s a big twist.

Warning – there’s plenty of bad language. My principal hero swears like a trooper. But this is intentional and very much an essential part of his personality. Please forgive him. My poor Primo is sad, lost and lonely, desperately trying to pretend his strength, and sullen bad behaviour is his defence against a world that does not want him. He knows no better.

My inspiration for this books was also a little unusual. I saw a fairly old film of Johnny Depp’s entitled The Brave. I was unable to sleep, and was sitting up in the early hours one chilly morning, watching late-night television. There were certain aspects of this film which moved me, and in particular the endless drag of hot dusty American roads. They seemed to symbolise a kind of hopelessness and typified the endless stretch of a fruitless life without ever arriving at a satisfying destination. The dust drifted in a hot and aimless wind towards an empty horizon. A sense of utter directionless foreboding seemed to dominate the film. The film is actually full of symbolism, and the futility of that dusty roadway haunted me. So then, since I was half asleep anyway, the plot of my new book started to materialise in my mind. It is absolutely nothing like the plot of the film – but that’s what sparked it off.

The next morning I started writing, and I couldn’t stop for months. I am much indebted to the extraordinary talents of Johnny Depp. My book is thanks to him.

This is a quirky novel. It’s not like any of my others, and it’s not like any other crime-mystery I have ever read. See what you make of it.

I am immensely proud of both books. I never publish anything unless I am proud of it – but the author cannot always be subjective. I would love to know what my readers think. If anyone cares to buy and read my novels, do please leave a review on Amazon or Goodreads, and do please let me know what you think.

An author has a burning need to communicate. My books are my way of communicating with the world. I would be so terribly happy if people cared to communicate back. I don’t want to sit here at the computer muttering to myself. I am talking to you. Please talk back. I would really love that. And I would love it if you enjoy the books I write. They are written for you.

Follow the links:http://www.amazon.com/Flame-Eater-Bar...http://www.amazon.com/Between-Barbara-Gaskell-Denvil-ebook/dp/B01B3K8U3Y/

And that is precisely what I have done. I am proud to introduce my two new publications, The Flame Eater, and Between.

These two novels are entirely different to each other. The Flame Eater is now my fourth historical novel In accordance with the others, this mystery-crime-adventure-romance is set in the late 15thcentury, the late medieval period which fascinates me and has become the period of my greatest research over the years. I may live in a small and very comfy cottage in the semi-rural beauty of Victoria, Australia. But I spend most of my time in medieval London, exploring the alleys and shadowed buildings, the winding power of the tidal Thames, and the palaces of the high clergy and the nobility. It is definitely my second home. Old London may exist purely in my head, but it is very real.

These two novels are entirely different to each other. The Flame Eater is now my fourth historical novel In accordance with the others, this mystery-crime-adventure-romance is set in the late 15thcentury, the late medieval period which fascinates me and has become the period of my greatest research over the years. I may live in a small and very comfy cottage in the semi-rural beauty of Victoria, Australia. But I spend most of my time in medieval London, exploring the alleys and shadowed buildings, the winding power of the tidal Thames, and the palaces of the high clergy and the nobility. It is definitely my second home. Old London may exist purely in my head, but it is very real.But inspiration varies for every book, and this one was actually born through the appearance of the hero Nicholas, fully formed in my head. The creation of any fictional character is a slightly strange process. People often ask, “Who is this character based on? Do you write about your friends or neighbours, disguising them under false names? Are all your characters secretly copied from members of your family, even the villains?”

Well – no – none of that. Perhaps some writers do this sort of thing, but frankly it is rare. Fictional characters are invariably born purely from the imagination. Some tiny seed roots itself in your mind and there it glues, takes shape and grows until it is a fully formed personality, quite separate from anyone you have ever known. After all, I make great efforts to present my characters as three-dimensional, but they can never be as multi-dimensional as anyone actually alive.

My initial idea stemmed from wondering how a very strong character might cope with being treated as beneath contempt and unworthy of attention by his arrogant family. Most books present such a man as angry, rude and vengeful, someone who will fight to prove his worth and lose his temper at the injustice of his treatment. Invariably he would be shown as impatient and furious. Authors seem to think such a young man will push and shout in order to vindicate himself.

But the haughty, rude and angry personality of so many books does not correspond to how I have discovered reality. I therefore decided that a character sufficiently strong and confident in spite of his family’s stupidity, would actually use humour as his defence rather than his temper, and would simply laugh at any attempts to undermine him. Thus Nicholas was born in my head, and I fell in love with him at once. He is now one of my favourite heroes, and he is certainly unusual.

At the same time, I learned some interesting and little known historical facts concerning Henry Tudor before his invasion of England, and that enlarged my plot. Then the final inspiration – I became interested in the psychology and injustice of the old system of arranged marriages and how terrible this must have been for young women forced into marriage against their will.

I disagree with much of what I have read over the years, for noble and wealthy women of that time were well accustomed from childhood to the idea of marrying a complete stranger, and for political motives, the dowry system and the need of family alliances. . Of course there were young women pressured into marriage against their wishes – but many were only too eager to marry someone of wealth and importance, who would then facilitate their own entrance into the world and enlarge their lifestyle and title. It is also fair to point out that many young men were pushed into marriage against their will. But most accepted the inevitable since a wedding was an alliance and rarely if ever seen as a romantic attachment. It was usually designed to aid both sides. However, this convoluted range of possibilities began to form itself into an interesting storyline in my mind.

And there it was – The Flame Eater was born.

I love my characters. Nicholas and Emma carry my book to its end, and the romance between them is unusual, unconventional, but – I hope – delightful. Yet there’s more. I don’t write romantic stories without interweaving plots. So here there is medieval history wrapped up in a crime mystery – and the romance weaves through it all.

My other recently published novel Betweencould not be more different. I have never written anything quite like this before –for a start, it is basically contemporary. This is a dramatic crime-mystery – a who-dunnit – no romance this time although there are many interweaving storylines and the plot is by no means straightforward. Mystery is the main ingredient, but this is no fantasy either. In other words – a crime drama with a twist. And it’s a big twist.

My other recently published novel Betweencould not be more different. I have never written anything quite like this before –for a start, it is basically contemporary. This is a dramatic crime-mystery – a who-dunnit – no romance this time although there are many interweaving storylines and the plot is by no means straightforward. Mystery is the main ingredient, but this is no fantasy either. In other words – a crime drama with a twist. And it’s a big twist.Warning – there’s plenty of bad language. My principal hero swears like a trooper. But this is intentional and very much an essential part of his personality. Please forgive him. My poor Primo is sad, lost and lonely, desperately trying to pretend his strength, and sullen bad behaviour is his defence against a world that does not want him. He knows no better.

My inspiration for this books was also a little unusual. I saw a fairly old film of Johnny Depp’s entitled The Brave. I was unable to sleep, and was sitting up in the early hours one chilly morning, watching late-night television. There were certain aspects of this film which moved me, and in particular the endless drag of hot dusty American roads. They seemed to symbolise a kind of hopelessness and typified the endless stretch of a fruitless life without ever arriving at a satisfying destination. The dust drifted in a hot and aimless wind towards an empty horizon. A sense of utter directionless foreboding seemed to dominate the film. The film is actually full of symbolism, and the futility of that dusty roadway haunted me. So then, since I was half asleep anyway, the plot of my new book started to materialise in my mind. It is absolutely nothing like the plot of the film – but that’s what sparked it off.

The next morning I started writing, and I couldn’t stop for months. I am much indebted to the extraordinary talents of Johnny Depp. My book is thanks to him.

This is a quirky novel. It’s not like any of my others, and it’s not like any other crime-mystery I have ever read. See what you make of it.

I am immensely proud of both books. I never publish anything unless I am proud of it – but the author cannot always be subjective. I would love to know what my readers think. If anyone cares to buy and read my novels, do please leave a review on Amazon or Goodreads, and do please let me know what you think.

An author has a burning need to communicate. My books are my way of communicating with the world. I would be so terribly happy if people cared to communicate back. I don’t want to sit here at the computer muttering to myself. I am talking to you. Please talk back. I would really love that. And I would love it if you enjoy the books I write. They are written for you.

Follow the links:http://www.amazon.com/Flame-Eater-Bar...http://www.amazon.com/Between-Barbara-Gaskell-Denvil-ebook/dp/B01B3K8U3Y/

Published on February 09, 2016 13:14

January 11, 2016

STAR WARS is back - Incase you hadn't heard!

In a cinema not so far, far away, I recently saw the new Star Wars film for the second time. And I honestly think I enjoyed it even more than I did the first time. It is pure, unassuming unchallenging and unadorned entertainment – especially for those who saw and enjoyed the original three way back a couple of centuries ago! Or thereabouts. And it seems there are plenty of us.

I was in a hospital waiting room yesterday when two doctors walked past, chatting to each other. One said, “So she’s his sister?” And the other said, “No, I think she must be his cousin.”

I was in a hospital waiting room yesterday when two doctors walked past, chatting to each other. One said, “So she’s his sister?” And the other said, “No, I think she must be his cousin.”

I knew exactly what they were talking about. Total strangers, doctors in white coats, in a hospital – and no names mentioned. But I still knew what their conversation was all about.

And by the way – no, she’s his cousin.

But it’s the business of villains, the black and white of good and evil, and the age old battle of light against the dark side that interests me here. It is not immediately obvious why we are so absorbed with villainous evil, when this is something that very few of us will ever actually experience in our own lives. And it is certainly not that we wish to. We hope beyond all else that the vile slaughter of a world war or terrorist hatred, the appalling sickness of a catastrophe such as the Nazi onslaught or the horror of the Rwanda genocide will never, ever touch us. So is it actually cathartic to keep such terrible deeds to the once-removed innocence of fictional theatre, cinema and novels?

We love a fictional villain. He (or she) is also a great deal more interesting to write about. Darth Vader will remain a favourite as do Sauron and Voldemort. - I must confess that I find Voldemort far more interesting than the adolescent Harry. In fantasy, extremes of evil are more acceptable – whereas in a contemporary novel it seems unnecessarily exaggerated to write about a villain of immeasurable wickedness. Yet in historical terms we are fascinated by those least attractive characters such as William the Conqueror, Henry VIII – and poor old Richard III, who was never a villain at all, but who continues to carry the glossy appeal of a terrible reputation.

Making villains believable is quite a challenge to the author – but having someone to hate, a character threatening the heroine, and working against our hero, is essential.

Star Wars has it right. Bring in a little sympathy – a little understanding – and definitely some mystery. But make that villain pitch black and the dark side as dark as possible. Shakespeare was a master. His villains may be wildly exaggerated (why do some people actually believe that his monstrous deformed demon is a historically accurate portrait of Richard III?) but they create the dramatic suspense and excitement that is needed in fiction and theatre. Importantly, even in their impossibly over-villainous portrayals, they manage to pull in our sympathy at the same time as we loathe them. In fact, I can be reading a book or watching a film which fails to impress me – it can even be rather poor – but if we have already been presented with the injustice perpetrated by the villain – then I will feel the need to read (and watch) on simply to see that evil creature receives his justified comeuppance!

In many ways the villain can be more important than the hero and heroine. But in most good books we can be absorbed, engrossed and bewitched by a joyous triangle of hero, heroine and villain – and thus we are cheerfully glued to the pages, awaiting the outcome.

So, who is your favourite villain?

And why?

I’d love to know.

I was in a hospital waiting room yesterday when two doctors walked past, chatting to each other. One said, “So she’s his sister?” And the other said, “No, I think she must be his cousin.”

I was in a hospital waiting room yesterday when two doctors walked past, chatting to each other. One said, “So she’s his sister?” And the other said, “No, I think she must be his cousin.”I knew exactly what they were talking about. Total strangers, doctors in white coats, in a hospital – and no names mentioned. But I still knew what their conversation was all about.

And by the way – no, she’s his cousin.

But it’s the business of villains, the black and white of good and evil, and the age old battle of light against the dark side that interests me here. It is not immediately obvious why we are so absorbed with villainous evil, when this is something that very few of us will ever actually experience in our own lives. And it is certainly not that we wish to. We hope beyond all else that the vile slaughter of a world war or terrorist hatred, the appalling sickness of a catastrophe such as the Nazi onslaught or the horror of the Rwanda genocide will never, ever touch us. So is it actually cathartic to keep such terrible deeds to the once-removed innocence of fictional theatre, cinema and novels?

We love a fictional villain. He (or she) is also a great deal more interesting to write about. Darth Vader will remain a favourite as do Sauron and Voldemort. - I must confess that I find Voldemort far more interesting than the adolescent Harry. In fantasy, extremes of evil are more acceptable – whereas in a contemporary novel it seems unnecessarily exaggerated to write about a villain of immeasurable wickedness. Yet in historical terms we are fascinated by those least attractive characters such as William the Conqueror, Henry VIII – and poor old Richard III, who was never a villain at all, but who continues to carry the glossy appeal of a terrible reputation.

Making villains believable is quite a challenge to the author – but having someone to hate, a character threatening the heroine, and working against our hero, is essential.

Star Wars has it right. Bring in a little sympathy – a little understanding – and definitely some mystery. But make that villain pitch black and the dark side as dark as possible. Shakespeare was a master. His villains may be wildly exaggerated (why do some people actually believe that his monstrous deformed demon is a historically accurate portrait of Richard III?) but they create the dramatic suspense and excitement that is needed in fiction and theatre. Importantly, even in their impossibly over-villainous portrayals, they manage to pull in our sympathy at the same time as we loathe them. In fact, I can be reading a book or watching a film which fails to impress me – it can even be rather poor – but if we have already been presented with the injustice perpetrated by the villain – then I will feel the need to read (and watch) on simply to see that evil creature receives his justified comeuppance!

In many ways the villain can be more important than the hero and heroine. But in most good books we can be absorbed, engrossed and bewitched by a joyous triangle of hero, heroine and villain – and thus we are cheerfully glued to the pages, awaiting the outcome.

So, who is your favourite villain?

And why?

I’d love to know.

Published on January 11, 2016 11:53

December 15, 2015

Christmas Curiositie's

In the northern hemisphere, winter can be long, dark and bleak. In ancient times this could mean starvation. The land froze and any remaining crops, edible roots and herbs disappeared under the snow. Farm animals were brought under cover, or killed and their meat preserved by smoke. Chickens stopped laying. Wild animals were harder to hunt, as they either migrated south or slunk deeper into the thicker parts of the forest. Sometimes hungry wolves crept from undercover and attacked vulnerable folk living in outlying huts. In those past centuries, poverty increased in winter, the sun barely rose, and older folk died of hypothermia. It was a season to fear.

In the northern hemisphere, winter can be long, dark and bleak. In ancient times this could mean starvation. The land froze and any remaining crops, edible roots and herbs disappeared under the snow. Farm animals were brought under cover, or killed and their meat preserved by smoke. Chickens stopped laying. Wild animals were harder to hunt, as they either migrated south or slunk deeper into the thicker parts of the forest. Sometimes hungry wolves crept from undercover and attacked vulnerable folk living in outlying huts. In those past centuries, poverty increased in winter, the sun barely rose, and older folk died of hypothermia. It was a season to fear.And so, the human spirit being what it is, from the earliest times it became the custom, then tradition, and finally the accepted religious practise, to congregate and celebrate during mid-winter, so lifting the hearts of an otherwise suffering people. A mid-winter feast could help save lives as well as encourage hope until spring came again.

In early Nordic and Celtic civilisations, this celebration was known as Yule, and it is surprising how many of the customs which originated then, have been carried forward even to today. The ancient worship of the tree, and in particular the evergreen which still carried its greenery amongst other trees which stood bare and stark – although finally brought to England as a Christmas festivity by Queen Victoria’s husband Prince Arthur – has its origins in Nordic times. Other Christmas customs date to the same period and pagan religion – decorations of ivy, holly and mistletoes for instance.

Christianity took the hint. It was easier to convert the pagans to the new religion if some of the most popular old practices were brought along with it. Besides, no date of birth for the infant Jesus is offered in the Bible, and therefore adopting Yule as Christ’s birth came as a sensible adaptation.

The Christian church brought new power to the seasonal festivities. Feasting and drinking continued of course, including the wassail cup – another pagan custom brought over into the Christmas tradition. This drink, taken from a huge wooden bowl and shared amongst all present, became a medieval delight. It can still be made today and the recipe is simple enough. Cider, or a combination of cider and ale, should be well spiced with nutmeg, cinnamon, ginger, cloves, juice and zest of a lemon or two, and some spoonful’s of honey. Chopped apples are sometimes added. This is simmered for some time and served very warm. Medieval recipes were never exact so adaptations are freely permitted, but few would still wish to share the same drinking bowl amongst the entire party.

Although there are now conflicting opinions worldwide concerning Christmas, most of us set out to enjoy the season in our own way. Some of us are more religiously inclined – others less. However, its origins are now accepted as specifically Christian and many complain that we are now too materialistic and concentrate our celebrations around eating, drinking and gift-giving instead of the nativity. But drunken self-indulgence was actually the original basis of the period, still occasionally known as ‘Yuletide’.

Christianity has of course, refined and brought glorious additions and although medieval celebrations were firmly based around the mid-winter traditions of feast and pleasure, the church was central and Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve was a great event. The season started on December 6th and continued officially until January 6th. Present giving – which at first took place on 12th Night, known as Epiphany, symbolised the arrival of the three kings and the precious gifts they brought to the infant Jesus. Travelling actors set up in town squares and re-enacted the story of the Nativity. Carols and songs of praise were a great part of these plays, and were carried over into the homes of the people who heard them. Mummings, religious and comedy plays were also very much the practise during the medieval Christmas, and all theatre blossomed as a result.

Food, of course, played a major part, and the principal meal on Christmas Day itself was traditionally, although only for those who could afford it or were permitted to hunt it, wild boar roasted on the spit and served whole with or without the proverbial lemon in its mouth. Mince pies were made with real meat which had been minced (hence the name, surprise, surprise!) and cakes, puddings and a hundred other delicacies were indulged on this most lavish day of the year. The medieval royal court gathered and celebrated in extraordinary style, courtesy of the king, but the ordinary folk gathered as well, meeting with friends and neighbours, and even the poor, the priests, nuns, and the beggars of Bedlam were expected to eat and drink and be merry.

Food, of course, played a major part, and the principal meal on Christmas Day itself was traditionally, although only for those who could afford it or were permitted to hunt it, wild boar roasted on the spit and served whole with or without the proverbial lemon in its mouth. Mince pies were made with real meat which had been minced (hence the name, surprise, surprise!) and cakes, puddings and a hundred other delicacies were indulged on this most lavish day of the year. The medieval royal court gathered and celebrated in extraordinary style, courtesy of the king, but the ordinary folk gathered as well, meeting with friends and neighbours, and even the poor, the priests, nuns, and the beggars of Bedlam were expected to eat and drink and be merry.The first day of the official Christian season of Christmas was St. Nicholas’ Day (December 6th). St. Nicholas was traditionally the saint who brought rewards to those who deserved them (although something quite different to the undeserving!). Father Christmas, based on the original saint, is a principally American adaptation – but also just another example of how nothing related to Christmas is new.

So whether the festivities marked the worship of the tree and nature, the need to break the bleak subsistence of mid-winter, or celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ – it has been Christmas time we have celebrated since the earliest times.

Published on December 15, 2015 12:35

November 21, 2015

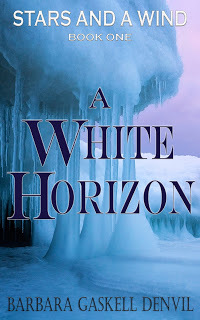

FANTASY BEYOND HORIZONS

A WHITE HORIZON leads us over the Arctic Circle and into unknown ice-lands where the endless wilderness is snow bound, and what lies beneath is hidden. The great white polar bear wanders, master of the sea-ice, and beyond the icebergs, the whales, seals and walrus claim their own dominions. Above soars the sea-eagle, hovering on the low wind. But is there some creature greater than any of these? And does that creature conform to human limitations – or does it transcend conformity?

Humanity has revised its beliefs many times over hundreds of years. As an example, once we thought the Neanderthals were little more than ignorant, brutal and almost mindless beasts. Now we know they were a race of intelligent beings who possibly inter-bred and certainly interacted with homo-sapiens at the time when both lived in fairly close proximity. We may carry Neanderthal genes. Over the centuries we have also discovered many new species of animals, first thought magical or fabricated, until they were gradually accepted as part of the natural fauna of our world.

Humanity has revised its beliefs many times over hundreds of years. As an example, once we thought the Neanderthals were little more than ignorant, brutal and almost mindless beasts. Now we know they were a race of intelligent beings who possibly inter-bred and certainly interacted with homo-sapiens at the time when both lived in fairly close proximity. We may carry Neanderthal genes. Over the centuries we have also discovered many new species of animals, first thought magical or fabricated, until they were gradually accepted as part of the natural fauna of our world.So what have we missed? What other creations existed in distant eras? What mysteries have still escaped our scientists? What may we still discover?

This book answers these questions and takes you roaming where few have dared go before.

Imagine yourself surrounded, isolated, and half buried in the greatest freeze any land can support. The wind whistles, slashing against you with the force of an ice-army. And yet this is no hurricane. As the long day continues, the wind will strengthen and the gale will take your breath away, pounding you down to the snow. The land is white and everything is frosted. Yet the sky is black, star studded, and cloudless, for this is the endless night of the arctic winter. The bitter cold trickles down the back of your neck, freezing you inside and out. And there is absolutely no escape.Set against the Nor’Way of the 9thcentury, as men hunt the white bear for its magnificent pelt, and sail the northern seas to plunder, trade and settle in the land of the Anglo-Saxons, this book explores both history and fantasy. The first of a trilogy entitled STARS AND A WIND, this novel A WHITE HORIZON travels deep within the mysteries of love and hatred, and follows Skarga and her young friend Egil as they face dangers which they could never have imagined before.

A WHITE HORIZON is available http://www.amazon.com/dp/B0184ZQFK6 andhttp://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B0184ZQFK6Kindle and Paperback editions available., the audio book to follow.

Published on November 21, 2015 23:45

October 30, 2015

Loving History

We owe so much to all the long struggle of those who lived, suffered and battled in the past, who strived to achieve their best, and finally died within their own developing lands and the considerable limitations and restrictions of their society. Whatever level of civilisation we can now claim, is all thanks to those long gone.

I have enormous sympathy for those who endured torture and execution in times when such things were considered right and just. I will not denigrate their pain and courage by pretending that the whip, the rack and the axe were not as fearsome as I know they were. And so in my books I do not spare the explanations and the descriptions. Thousands of men and women deserve the honour of their stories told without pretence or a softening disguises. In those past centuries there were times, in particular under certain dynasties, when torture was common enough. There were also centuries devastated by the plague. Two English kings and thousands of their subjects died of dysentery, in all its agonies and misunderstood horror. The small pox was a terrible scourge, and later it was the equally misunderstood syphilis which was the most terrifying disease. But the actions of kings, lords and ordinary folk could be just as fearsome. I do not believe in turning away or refusing to acknowledge the misery, astonishing perseverance and bravery of our ancestors. I believe it right to tell their stories in honest truth, and not belittle their suffering by being too squeamish to describe what they endured.

But it was not all terrible and there has always been love, loyalty, friendship, kindness and determination to survive and improve the conditions of those who needed help. Long before the age of the Welfare System, the poor, the widowed and the sick were helped by their lords and their neighbours, out of loving kindness. And my books also include this care and happiness, and in particular the love – that humanity has always found indispensable to life.

I write historical fiction, and although most of my plots and characters are fictional, I set these stories against genuine backgrounds with genuine historical characters who take their place alongside those I have invented. I am fiercely devoted to the truth and keep my facts accurate. So where some real event of the past occurs on my pages, then I am quite sure I have told it correctly, at least within the limitations of those details still available to us now. But I equally feel obliged to present the fiction as accurately as the fact. We owe a great deal to the past and should honour it with accuracy. Remember, those who lived in the distant years have made us what we are today.

We now strive to live as comfortably as we may, principally because we have learned from the past. Or have we? The Christian Church was once as tyrannical and intolerant as those inspiring terrorism today. Great wars were fought to prove that God was on one side – or the other. Torture was used to convince heretics of their mistakes, and then they were burned alive to ‘cleanse’ their souls. More horror was commuted in God’s name than in the name of human greed and ambition. Although – of course – in many cases the greed and ambition of the old church itself was the direct cause. Over the centuries most countries and religions have developed through trial and error, suffering and grief, pain and experience. It has been our worst behaviour that has gradually taught us better.

In a similar vein, it is the diseases of past centuries which enabled us to develop the understanding of germs and hygiene, to discover medicines, and the humane desire to cure everyone we can. So it is through the ignorance and vice long-gone that we now understand how we must attempt to improve the world and the lives of those who share it with us. Hundreds of years ago we held justice in trembling hands and expected little equality. Medieval status, ambition, avarice and acquisitiveness were considered admirable qualities. A little later, to torture in order to produce confessions was considered logical and necessary – to invade and fight a battle that killed thousands was considered a valid method for proving strength, enacting revenge or acquiring a throne. A woman was necessary for breeding, and could be obtained through negotiation with her parents, while wives, children and servants could all be legally whipped if their ‘master’ believed they deserved punishment. .

I won’t continue. Some men were always kinder than others, and not all women were abused – nor were they all averse to abusing others. But these things were accepted back then – whereas now in the Western World, they are not. Even though they still occur, they are condemned. And that is precisely because we have learned from the past. We are hardly perfect, but it is the effort, failures and successes of our ancestors which have gradually taught us not to fall into the faults they could not escape themselves.

So my books of historical fiction are as accurate as I can make them, and do not quake at the presentation of the truth in all its loving kindness and sacrifice, caring and, yearning, pain, disease, blood and injustice. I will not insult those who suffered by pretending that their agonies were no more than a sneeze or a hiccup. I respect and I salute the past. But it is not only my desire for accuracy that drives my writing. I also adore the challenges of the past, and so both my plots and my characters inspire me. My characters in particular soon become as real to me as the genuine historical figures that appear in my books.

I should love to share my enthusiasm with you. So may I introduce my three historical novels – now available worldwide on Amazon both as ebooks and in print -

BLESSOP’S WIFE

1483 and Edward IV wears England’s crown, but no king rules unchallenged. Often it is those closest to him who are the unexpected danger. When the king dies suddenly, rumour replaces fact – and Andrew Cobham is already working behind the scenes.

Tyballis was forced into marriage and when she escapes, she meets Andrew and an uneasy alliance forms. Their friendship will take them in unusual directions as Tyballis becomes not only embroiled in Andrew’s work but also in the danger which surrounds him.

A motley gathering of thieves, informers, prostitutes and children eventually joins the game, helping to uncover the underlying mystery and treason, as the country is brought to the brink of war.

SATIN CINNABAR

Bosworth was not the bloodiest battle in history, but it changed the future of England forever. The king is dead. Long live the king. Recovering consciousness on the battlefield, Alex, seeing the devastation around him, knows the threat to his life is by no means over. But when the great lords of the land make war, everyone is at risk. The local population, the besieged villagers, the respectable wives and their daughters threatened with rape, the ravaged farmlands and the looted properties are considered simply collateral damage. So Kate, frightened but defiant, dresses as a boy to escape the attentions of wandering soldiers, deserters and drunken victors.

Henry Tudor claims victory and the throne. Alex fought on the wrong side and does not expect favour, but what he never expected was to discover the murdered corpse of his favourite cousin. And nor – once discovered – to become the principal suspect.

Kate and Alex meet in unusual circumstances but romance must wait as Alex narrowly avoids execution. First there is as murderer to uncover and a myriad of investigations to instigate into what has happened, a new regime to accept, disguises to adopt and discard, and finally a very different life to understand.

SUMERFORD’S AUTUMN

With three older brothers, Ludovic expects no inheritance, no sympathy and no surprises. He has taken to a life of secret smuggling as his solitary source of income. But he is not the only one in the family with secrets and Sumerford Castle is a home of of brooding unease. Yet amid the conflict, Ludovic finds love, unexpected and passionate. Alysson does not at first appear to be his match, but he is determined to find a way to keep her.

These are dark years in England’s history and with the first of the Tudor dynasty on the throne, the fledgling rule is under threat from other claimants to the crown. One of the Sumerford brothers supports the 'pretender' Perkin Warbeck and gradually draws Ludovic into the conspiracy. Treason, if discovered, means certain death but when escaping from one danger, the twists of mystery and subterfuge can lead to others.

Following arrest, imprisonment and torture in the Tower, Ludovic seems likely to lose his very minor fortune, his barely awakening romance, and possibly his worthless life. But once again, not everything is as predictable as it would seem.

Sumerford's Autumn on Amazon

Satin Cinnabar on Amazon

Blessop's Wife on Amazon

My Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/B.GaskellDenvil

I have enormous sympathy for those who endured torture and execution in times when such things were considered right and just. I will not denigrate their pain and courage by pretending that the whip, the rack and the axe were not as fearsome as I know they were. And so in my books I do not spare the explanations and the descriptions. Thousands of men and women deserve the honour of their stories told without pretence or a softening disguises. In those past centuries there were times, in particular under certain dynasties, when torture was common enough. There were also centuries devastated by the plague. Two English kings and thousands of their subjects died of dysentery, in all its agonies and misunderstood horror. The small pox was a terrible scourge, and later it was the equally misunderstood syphilis which was the most terrifying disease. But the actions of kings, lords and ordinary folk could be just as fearsome. I do not believe in turning away or refusing to acknowledge the misery, astonishing perseverance and bravery of our ancestors. I believe it right to tell their stories in honest truth, and not belittle their suffering by being too squeamish to describe what they endured.

But it was not all terrible and there has always been love, loyalty, friendship, kindness and determination to survive and improve the conditions of those who needed help. Long before the age of the Welfare System, the poor, the widowed and the sick were helped by their lords and their neighbours, out of loving kindness. And my books also include this care and happiness, and in particular the love – that humanity has always found indispensable to life.

I write historical fiction, and although most of my plots and characters are fictional, I set these stories against genuine backgrounds with genuine historical characters who take their place alongside those I have invented. I am fiercely devoted to the truth and keep my facts accurate. So where some real event of the past occurs on my pages, then I am quite sure I have told it correctly, at least within the limitations of those details still available to us now. But I equally feel obliged to present the fiction as accurately as the fact. We owe a great deal to the past and should honour it with accuracy. Remember, those who lived in the distant years have made us what we are today.

We now strive to live as comfortably as we may, principally because we have learned from the past. Or have we? The Christian Church was once as tyrannical and intolerant as those inspiring terrorism today. Great wars were fought to prove that God was on one side – or the other. Torture was used to convince heretics of their mistakes, and then they were burned alive to ‘cleanse’ their souls. More horror was commuted in God’s name than in the name of human greed and ambition. Although – of course – in many cases the greed and ambition of the old church itself was the direct cause. Over the centuries most countries and religions have developed through trial and error, suffering and grief, pain and experience. It has been our worst behaviour that has gradually taught us better.

In a similar vein, it is the diseases of past centuries which enabled us to develop the understanding of germs and hygiene, to discover medicines, and the humane desire to cure everyone we can. So it is through the ignorance and vice long-gone that we now understand how we must attempt to improve the world and the lives of those who share it with us. Hundreds of years ago we held justice in trembling hands and expected little equality. Medieval status, ambition, avarice and acquisitiveness were considered admirable qualities. A little later, to torture in order to produce confessions was considered logical and necessary – to invade and fight a battle that killed thousands was considered a valid method for proving strength, enacting revenge or acquiring a throne. A woman was necessary for breeding, and could be obtained through negotiation with her parents, while wives, children and servants could all be legally whipped if their ‘master’ believed they deserved punishment. .

I won’t continue. Some men were always kinder than others, and not all women were abused – nor were they all averse to abusing others. But these things were accepted back then – whereas now in the Western World, they are not. Even though they still occur, they are condemned. And that is precisely because we have learned from the past. We are hardly perfect, but it is the effort, failures and successes of our ancestors which have gradually taught us not to fall into the faults they could not escape themselves.

So my books of historical fiction are as accurate as I can make them, and do not quake at the presentation of the truth in all its loving kindness and sacrifice, caring and, yearning, pain, disease, blood and injustice. I will not insult those who suffered by pretending that their agonies were no more than a sneeze or a hiccup. I respect and I salute the past. But it is not only my desire for accuracy that drives my writing. I also adore the challenges of the past, and so both my plots and my characters inspire me. My characters in particular soon become as real to me as the genuine historical figures that appear in my books.

I should love to share my enthusiasm with you. So may I introduce my three historical novels – now available worldwide on Amazon both as ebooks and in print -

BLESSOP’S WIFE

1483 and Edward IV wears England’s crown, but no king rules unchallenged. Often it is those closest to him who are the unexpected danger. When the king dies suddenly, rumour replaces fact – and Andrew Cobham is already working behind the scenes.

Tyballis was forced into marriage and when she escapes, she meets Andrew and an uneasy alliance forms. Their friendship will take them in unusual directions as Tyballis becomes not only embroiled in Andrew’s work but also in the danger which surrounds him.

A motley gathering of thieves, informers, prostitutes and children eventually joins the game, helping to uncover the underlying mystery and treason, as the country is brought to the brink of war.

SATIN CINNABAR

Bosworth was not the bloodiest battle in history, but it changed the future of England forever. The king is dead. Long live the king. Recovering consciousness on the battlefield, Alex, seeing the devastation around him, knows the threat to his life is by no means over. But when the great lords of the land make war, everyone is at risk. The local population, the besieged villagers, the respectable wives and their daughters threatened with rape, the ravaged farmlands and the looted properties are considered simply collateral damage. So Kate, frightened but defiant, dresses as a boy to escape the attentions of wandering soldiers, deserters and drunken victors.

Henry Tudor claims victory and the throne. Alex fought on the wrong side and does not expect favour, but what he never expected was to discover the murdered corpse of his favourite cousin. And nor – once discovered – to become the principal suspect.

Kate and Alex meet in unusual circumstances but romance must wait as Alex narrowly avoids execution. First there is as murderer to uncover and a myriad of investigations to instigate into what has happened, a new regime to accept, disguises to adopt and discard, and finally a very different life to understand.

SUMERFORD’S AUTUMN

With three older brothers, Ludovic expects no inheritance, no sympathy and no surprises. He has taken to a life of secret smuggling as his solitary source of income. But he is not the only one in the family with secrets and Sumerford Castle is a home of of brooding unease. Yet amid the conflict, Ludovic finds love, unexpected and passionate. Alysson does not at first appear to be his match, but he is determined to find a way to keep her.

These are dark years in England’s history and with the first of the Tudor dynasty on the throne, the fledgling rule is under threat from other claimants to the crown. One of the Sumerford brothers supports the 'pretender' Perkin Warbeck and gradually draws Ludovic into the conspiracy. Treason, if discovered, means certain death but when escaping from one danger, the twists of mystery and subterfuge can lead to others.

Following arrest, imprisonment and torture in the Tower, Ludovic seems likely to lose his very minor fortune, his barely awakening romance, and possibly his worthless life. But once again, not everything is as predictable as it would seem.

Sumerford's Autumn on Amazon

Satin Cinnabar on Amazon

Blessop's Wife on Amazon

My Facebook Page: https://www.facebook.com/B.GaskellDenvil

Published on October 30, 2015 15:37

September 6, 2015

The Dastardly Death Of William, Lord Hastings

Arms of Sir Wm. HastingsIt appears that the traditional assumptions surrounding the execution of William, Lord Hastings in June of 1483, generally incline towards the idea that the Lord Protector, Richard Duke of Gloucester, simply lost his temper and so, without lawful trial or consultation, ordered the immediate beheading of his previous friend, virtually on the spur of the moment.

Arms of Sir Wm. HastingsIt appears that the traditional assumptions surrounding the execution of William, Lord Hastings in June of 1483, generally incline towards the idea that the Lord Protector, Richard Duke of Gloucester, simply lost his temper and so, without lawful trial or consultation, ordered the immediate beheading of his previous friend, virtually on the spur of the moment.This assumption is derived from depictions in Tudor literature claiming that the Duke of Gloucester was infuriated by Hastings’ rigid support of the uncrowned Edward V, contrary to the wishes of the wicked duke who was eager to usurp the throne in the prince’s stead. This account of these events was written down after many preceding decades of indoctrination, when the Tudor-era orthodoxy of the usurping, murdering king had become imprinted on popular consciousness.

The writer who invested the confrontation with its best-known dramatic scenario, later adopted by Shakespeare, was Sir Thomas More, whose various attempts at a ‘history of Richard III’ are loathed by some, beloved of many, and seriously analysed by all too few. Since there exists no official contemporary documentation of exactly what happened, More’s chatty details attract those searching for explanations. It is often further assumed that, although More’s various elaborate accounts concern a time when he was a child and certainly not present, on the occasion of Hastings’ death, John Morton, Bishop of Ely, was certainly present and must therefore have witnessed exactly what happened. More, it is said, would thus have been told the truth by Morton some years afterwards when the young Thomas later lived as a page in Morton’s household.

However, regardless of assumptions, Thomas More himself reveals no source of information for his dramatic construction concerning the Duke of Gloucester’s peremptory execution of Hastings pursuant to a hissy fit. It is unsupported by any contemporary source, although the execution itself was condemned by some contemporary chroniclers. Sadly, very few later commentators appear to have bothered to take into account the bias of those contemporary accounts, or the probable circumstances (leaving dramatics aside) that actually led to Hastings making an attempt on Gloucester’s life.

Let us take one point at a time:1) The incident occurred in the context of two events which are generally agreed to have preceded it, i.e. the disclosure that there was an impediment to Edward IV’s marriage with Elizabeth Woodville which rendered their offspring potentially illegitimate, and the discovery by Gloucester of threats to his life which prompted him to call for protection in the shape of forces from the North, combining in an atmosphere of heightened tension and insecurity.

2) Contemporary accounts report that Hastings was officially accused of treason. The simultaneous arrests of several others support the existence of a treasonous conspiracy. Any assumption that this accusation of treason was untrue is unsupported by any existing evidence. The crime of treason at that time was the most serious in the land, and could not be slung at just anyone, in particular someone as powerful as Lord Hastings, without any substantiation. In days leading up to the arrest and execution, Hastings is reported to have been seen visiting the houses of Morton and others who were caught up in the arrests. Morton and Hastings were most unlikely companions and this report – if true – raises considerable suspicion.

3) Some people mistakenly suppose that the crime of treason related only and exclusively to violent actions against the ruling monarch’s person. This is untrue and there are many sources which indicate that treason took many and varied forms. The further assumption that Hastings was simply attempting to support the true king (the young uncrowned Edward V) against the actions of the Protector, and therefore his attack on the Protector was not treason but loyalty to the crown, is an even further exaggerated train of suppositions without support, evidence, or even logic.

4) Others accused of having been involved in the same treason were arrested at the same time:- three present in the council chamber, and several others across London – their arrests carefully timed to coincide. This points to the uncovering of a treasonous conspiracy and the planning of a lawful reaction which would stop that treason before it became any more dangerous.

5) There is an account of a public proclamation made immediately after the execution, regarding the treason and the culprits’ arrest. There was neither secrecy nor lack of explanation given to the public concerning the situation. The accusation of treason and its consequences remained undisputed by any legal challenge or recorded public outcry at the time.

6) More’s account, written so many years later, denies the legality of the Protector’s actions. But More had no possible way of knowing the details he recounted. The mighty and extremely busy John Morton (by then Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord Chancellor) chatting at length with his insignificant page and telling him stories of what happened many years previously, is not only highly unlikely but somewhat ingenuous. Indeed, Morton would rarely even have been at home let alone conducting cosy discussions with one of his pages. However, if such an improbable little scene did take place, the fact that Morton himself was one of those arrested and accused of treason, would certainly place a huge doubt on the veracity of any tale he told.

7) Richard of Gloucester’s proven record of rationality, of intelligent administration and commitment to the rule of law, would make this supposed hissy fit exceedingly out of character.

8) The arrests and following events took place in a council meeting at the Tower, in front of members of the Royal Council – the most powerful and influential lords of the land, together with their attendant officers. It is both naive and absurd to suppose that Richard could behave in some highly improper and illegal manner in such company without consequences to himself including a virtual battle in the council chamber.

9) Kindly old Hastings, simply standing loyally by the rights of his old friend’s son, is a total illusion. Hastings was a massively ambitious man. His many years of fighting bitterly against Thomas Grey, Marquess of Dorset, the queen’s elder son and Lord Rivers, her brother, (largely regarding disputed land borders) show him to have been ruthless and capable of cruelty. He had recently quarrelled with Edward IV and been deprived of some of his power, but this was – after warnings given – returned to him just before the king’s death. Hastings was certainly no cosy daddy-figure.

10) As for the allegedly illegal execution – and this is the most important ingredient in the murky soup of supposition – the accepted legal powers of the High Constable, (one of Richard of Gloucester’s long-held and most powerful offices) empowered him to hold an immediate trial of Hastings for treason in that place and at that time, and to pass sentence without leave of appeal. The other members of the council present would have stood witness, thus there was no outcry against the following execution. Since no documentation survives (and indeed the Court operated under the Law of Arms and was not required to keep records), it is impossible to say if any such trial took place. There is no specific evidence that it happened. Nor is there any specific evidence that it did not. However – since Richard of Gloucester was most certainly empowered to hold such a trial, it is logical and natural from what is known of his concern for the justice system, that he would have used the legal powers at his disposal. What is now doubted and frowned upon by modern judges with little or no comprehension of the medieval mind, would have seemed utterly right in those days – and in fact utterly necessary according to the situation. Summary courts with powers of life and limb, such as that of the High Constable, were important elements in the exercise of authority during the Middle Ages, and in fact Hastings himself presided over just such a summary court at Calais.

For this knowledge I am entirely indebted to Annette Carson and her recently published book RICHARD DUKE OF GLOUCESTER, AS LORD PROTECTOR AND HIGH CONSTABLE OF ENGLAND http://www.annettecarson.co.uk/357052369 which outlines with considerable clarity and detail, based on existing documentation and clear historical precedent, the official powers the Duke of Gloucester held in 1483. This book does not set out to prove the rights and/or wrongs of the situation regarding Hastings’s execution, nor does it prove that any trial took place. It does indicate, however, that a trial could immediately have been called, and that if the proceedings found him guilty of treason Hastings would have been justly and legally executed.

In the first months of 1483 after King Edward’s death, the country was in a perilous position, and it was the duty of the Lord Protector and Defender of the Realm to keep the land and its people safe. There had already been an attempt to raise an army and civil war might have ensued (certainly the queen’s family continued organising uprisings, which came to fruition in the autumn months). It was Richard’s principal responsibility to be aware of all dangers and put a stop to them before the risk might escalate. Such an attitude must have been paramount when faced with whatever treason was discovered. That his actions are now seen as suspicious is a function of the villainy later attributed to his actions, and appears to ignore the pressures and demands involved in his personal responsibility for national security.

Today, amongst those interested (whether or not they have researched the era or the life of Richard III at all) there is a somewhat irritating attitude by which if you argue and judge Richard III guilty of something, then you are being open minded and unbiased. Whereas if you argue and judge him innocent, then clearly you are prejudiced and are making an attempt to exonerate and justify him and treat him as a saint.

But most of those who exhibit the former attitude appear to think the powerful lords of the late fifteenth century must have been weaklings and brainless puppets, too stupid or frightened to stand up for themselves. They sat meekly, it seems, while the wicked Duke of Gloucester got away with anything and everything. It is unwise to so vastly underestimate the over-riding power of the lords and the church, the three estates of parliament and the Royal Council during this period. Had they so meekly acquiesced to apparent villainy, they would, in fact, have been complicit to it. Instead no single man ever held absolute total power, not even the king.

See Annette Carson’s book RICHARD III; THE MALIGNED KING http://www.amazon.com/Richard-III-Maligned-Annette-Carson/dp/0752452088/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1436415497&sr=1-1&keywords=annette+carson which remains a reliable source for the arrest and execution of Lord Hastings and the other important events of 1483 following the death of King Edward IV.

Published on September 06, 2015 14:43

June 22, 2015

Minimalism In Word and Deed

Advice is not a four letter word. We all like to give it, and we are often keen to search it out and follow the advice of others when we lack confidence ourselves. But as an author I have become more and more dubious regarding advice so frequently given on the practice of writing itself.

Advice is not a four letter word. We all like to give it, and we are often keen to search it out and follow the advice of others when we lack confidence ourselves. But as an author I have become more and more dubious regarding advice so frequently given on the practice of writing itself.There is plenty of such advice to writers out there, and a good deal of it refers to strict minimalism, cutting out all detail, and never using 10 words when you could use two.

So which is preferable? "He went," or "He ambled, enjoying the warm sunshine on his back."

There have always been brilliant authors who followed the belief in brevity and kept to the Hemmingway style. Indeed, many years previously John Ruskin told us - "It is excellent discipline for an author to feel that he must say all that he has to say in the fewest possible words, or his reader is sure to skip them." But then Ruskin got a lot of things famously wrong and I feel it is somewhat patronising to assume your reader is an impatient and somewhat shallow soul of limited focus and lacking in concentration.

“Murder your darlings,” advised Kipling. But there are a good many differing ideas about what constitutes a ‘darling’ – and Kipling does not seem to be talking about cutting out everything, although this is what some people assume he meant.

The darlings we write and sadly want to hang on to are often those over-precious phrases of cleverly worded irrelevance. We, as authors, may feel very proud of a precocious little joke, or a suddenly poetic description. Purple prose, for instance. These are what is meant by our ‘darlings’. So yes, cut them out, even though we are lovingly proud of them. They look out of place and we need to crop ruthlessly with such over-indulgent violate passages.

But this does not mean cut – cut – cut. Some critics seem to think we should end up with a book 6 pages long. Or perhaps we should cut them too?

Some types of books call for brevity. The Regency romance can be a delicious frolic of no more than 100,000 words. Such a book speeds along without need of heavy plotting, considerable action or even depth of characterisation. A modern crime drama can also sizzle in 120,000 words or less. A fashionable contemporary novel of mental anguish about a woman who lives an even more boring life than we do ourselves, can be self-consciously arty in less than 80,000 words. Indeed – the shorter the better!

But what about Dickens? What about Hardy? Tolstoy (although no, I haven’t read War and Peace lately either – once was enough) In fact, Shakespeare’s plays were considerably longer than the average theatrical performance today. And coming up to date, there’s Tolkien. Dorothy Dunnett. Even Harry Potter. So many of the greats and so many of the best sellers are massive meaty stories, and their authors are not minimalistic at all. Alright, none of us pretend to be at the standard of these masters. But they had to start somewhere too.

Some of the classics are very thin books, but not so many. The great novels of the past were rarely scant or flimsy. And they are still adored and admired. If you are setting out to write a complicated story with a large cast of characters and a many layered plot, then I believe that characterisation and detailed episodes which promote storyline – suspense – anticipation and atmospheric description, should be used to the utmost effect. No we don’t need to know what every character is wearing at every moment or have to wade through pointless dialogue discussing the weather – but that is more to do with the quality of writing rather than simply being told to cut and cut again.

In this age of publishing desperation, with traditional publishers slow to catch up with modern trends, and either going bankrupt or having to merge into fewer and larger companies, it is commercially helpful to keep your book short. Some literary agents will not even consider a novel longer than 150,000 words. Some won’t even open a manuscript over the 120,000 mark. I understand. Commercial profits rely on low printing costs. This is another reason why self-publishing can be attractive.

But my point goes beyond this. I am strictly interested in what actually constitutes a good book – and I utterly refute the idea that cutting out all description and layering while keeping word count to the absolute minimum, automatically means good writing.

I would rephrase John Ruskin’s advice and say, “The number of words you use is less important than the quality of plot, characterisation and style you use. Your reader will not skip as long as your writing keeps them utterly absorbed.”

I am biased, of course. I love long books. I want a novel – of whatever genre – to carry me into its world, transport me into its exciting and vibrant life – and to immerse me in its emotional diversity. I want to lose myself in the pages and that means a big feast of a book where I can swim and climb, savouring the beauty of its words and cherishing every tasty morsel.

I write long books too. And the same delight applies. I disappear each morning into a new world of dark mystery and adventure. And words are my roads, my map, my milestones, and my rumbling, rattling coach, lined with velvet and pulled by magic.

And of course, I do not denigrate short books in general, they can be delightful, frivolous and fun. There are sometimes advantages in a quick snack or a romantic dalliance. But it’s those magnificent heavyweights that usually end up being my favorites.

Oh – and one more thing. If we, as authors, must take the advice of others, let me suggest the delicious and utterly convincing advice of Somerset Maugham, who said – "There are three rules for writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are."

Published on June 22, 2015 10:30

May 2, 2015

The Same Door

I am standing alone. Except for the shadows, the room is empty: Dark and sinister, they billow around me like heavy curtains in a silent wind. I am lost, the emptiness both within and without. But I cling to hope.

My hope is a doorway which stands before me, the only escape from this place of dark depression. The way out glows brilliantly and is utterly enticing, offering me everything I need and desire. But even as I rejoice in its promise, the door is closing in my face.

I stand bewildered as my hope dies. The door closes remorselessly until the magical light beyond is no more than a sliver. For a moment the light still shines – but then it is taken from me and I stand in complete darkness.

But in some part of me a small fact registers: there was no click as the door shut, no sound at all. I feel abandoned. But there has been no material confirmation of finality. I cling to hope … yet I can see nothing and what else can I trust but my own eyes? The light of hope is quite gone.

Or not? Have I misunderstood?

Because although the door has shut in my face, a crack as slim as an echo is once more shimmering with that same wonderful light. Only the barest suggestion, but I see it.

And the light grows and I realise that the door is swinging right through; it is opening onto

the other side now and the way through is widening.

Of course, it’s a swing door! It never actually shuts at all! Or should I say that even as it was closing, it was also opening again. What I thought was the end of the light was the swing from one room to

another. Not the end at all but a beginning. Now opening wider still, it promises so much. Soon I will be able to walk through, out of the dark and into that light.

another. Not the end at all but a beginning. Now opening wider still, it promises so much. Soon I will be able to walk through, out of the dark and into that light.Taking my first step towards this new disclosure, I hear a voice in my head say, very distinctly, IT IS THE SAME DOOR.

And now I know that there is nothing that closes forever. Success and failure are the same door. The same thing. It depends which side of the door you are looking from.

We authors are so vulnerable to the self-perception of failure. We are not helped by the inevitability of our careers involving a good deal of solitude. Alone and concentrated on our imaginations, we can fall too easily into believing in our own defeat. And not only authors. Our society is fixated on achievement – winners or losers – whether in wealth or simple satisfaction. And, in despair, who remembers that failure is the necessary first step towards success? There are few more essential building blocks for happiness and success than those initial experiences of failure.

And it’s no use trying to squeeze past while the door is closing on you. You’d simply be squashed and achieve nothing. You have to wait until the door has swung right through and is opening once more, just for you. Timing is everything. While the door is shutting, don’t despair. Don’t collapse in a puddle amongst those dank dark shadows, feeling miserably sorry for yourself.

Just remember, IT’S THE SAME DOOR.

And it is your precious self standing in front of it. Rather than valuing ourselves on some external scale of success, judged through the eyes of others, we would better value ourselves for the truth of our own inner self.

You are the only person in the world who can represent your true self. Nobody else brings to the world exactly what you do; you are unique and therefore precious just as you are – this is your value. Once – in spite of inevitable failures – we recognise our own intrinsic value and love it for what it is, then the door can swing through and open into that brighter future.

You are the only person in the world who can represent your true self. Nobody else brings to the world exactly what you do; you are unique and therefore precious just as you are – this is your value. Once – in spite of inevitable failures – we recognise our own intrinsic value and love it for what it is, then the door can swing through and open into that brighter future. Because, whether that brightness is yet visible or not, IT’S THE SAME DOOR.

That initial sense of failure is a transitory affair – the door CAN’T open onto the other side until it has first closed in our face.

The door that closes in your face and the door that opens to opportunity – are – quite simply – the same door.

Published on May 02, 2015 07:38

February 20, 2015

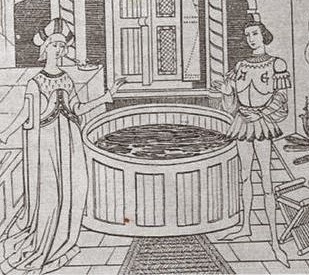

Pollution And Privies: Medieval Delights

The question of hygiene in past eras is a fascinating one. It is a subject which seems to invite a feast of different assumptions – and I have heard everything from “They were filthy – never washed because the church said it was sinful – and stank the place out,” through to: “No, they were regular bathers, washed their clothes frequently and smelled no worse than we do today.” The truth is probably somewhere in the middle, but during the period that interests me which is the late 15th century, I veer more towards a belief in cleanliness rather than the opposite. However – nothing is ever quite that simple.

We have it on record, for instance, that in one large noble household all linen, including the intimate apparel of the nobility themselves, was thoroughly washed every three days. We are given to assume

from this that bedding was changed often, also shifts and sweaty shirts, whilst the gentlemen changed their braies (underpants) that frequently. But of course this information, although fascinating, is as deceptive as most of the rest.

Since wealthy gentlemen would certainly have owned more than one pair of braies, it is perfectly possible that they put on a clean pair every morning rather than waiting for wash-day, and the three day wash cycle would therefore be irrelevant in that respect. On the other hand, some men might have refused to keep such hygienic habits. Washing whatever was passed to the laundry girls every three days does not prove everyone discarded their dirty underwear that often. Nor can we be sure that other establishments carried out laundry duties with the same regularity. Some may have been even more diligent. Others may have been far more lax.

I also imagine that having been jousting for most of the day, or after having spent several days in the saddle, (not an unusual practise) the clothes would be sweaty and grimy, however often they were usually washed at home. So cleanliness was considered advisable up to a point – but what probably did not happen was the sort of shocked disgust at dirt and smells which we now experience. They would all have been far more accustomed to grime. So his grubby knickers might not be the worst of your problems when your gallant knight came riding home.

Bed and table linen was regularly washed and then spread out on the hedges to dry in the sun. However, the nobility’s outer clothes were rarely washed. The great sweeping velvets and heavy brocades with their golden laces, fur trimmings and satin ribbons were kept clean by extensive brushing and wiping, and with the use of steam and Fuller’s Earth. More personal hygiene was considered equally important. Teeth were cleaned with specially cut birch twigs, and soap came in various different qualities from the cheap brown liquid available for the poor, up to the expense of solid white Spanish soap.

On the other hand, human waste was an accepted part of the everyday experience and was used as part of normal manure spread as fertilizer on country crops. Urine was considered a useful ‘crop’ in itself and was used in the process of tanning hides and in dying fabrics amongst others. Animal blood and brains were generally allowed to disappear into the shallow central gutters around the butchers’ quarters in any township, the animals that roamed most streets (dogs, goats, pigs and others) would add their own contributions, and most mornings the average housewife would empty the family chamber pots into the gutters as well. Much of this muck would remain until washed away by the rain, although large towns employed ‘raykers’ to clear the gutters on a regular basis, while diligent shopkeepers cleaned the gutters directly outside their own premises – sweeping the filth down to the next shop along!