Anna Beer's Blog, page 2

October 4, 2015

piano, piano

A few months ago I realised I was running on empty, emotionally (having been thrust into the unlikely and ill-fitting role of carer through the winter and into the spring) and intellectually, being fresh out of words and ideas, since they had all been poured into the manuscript of my book. Time has passed, and now the patient is recovering well, and the manuscript is in the capable hands of my publishers, the alchemists who will transform a computer file into a living, breathing book.

So, with a slight sense that I was going all ‘Eat, Pray, Love’-ish, I decided that, in addition to food (which has ever and always been my salvation, so no change there); prayer (which does have its moments, even for those of us without faith, if viewed in George Herbert’s inimitable words as ‘something understood’); and love (oops, it will now become clear that I have not actually read Eat, Pray, Love and so I am not sure whether this is an American euphemism for sex, which would mean this post veering into unchartered waters) but fortunately this sentence is now so long that even the most careful reader will have lost the will to follow it to its logical conclusion, allowing me, in a rhetorical sleight of hand, to return to the main clause: I decided that I wanted to learn.

So it is that I am writing this in Otranto, an ancient city port poised on the easternmost point of the heel of Italy (next stop Albania), and feeling extremely anxious about tomorrow morning. I am starting un corso gruppo at a local language school, the first step, I hope, towards taking the Italian government’s CILS exam (level to be decided) towards the end of November. Domani, sono una studentessa! (Is that right? Please tell me it’s right! And I’ve not even started…this is not going well.)

I chose Otranto somewhat blindly, seduced by the thought of the Italian south (particularly once we get to November) and thinking it would somehow be more authentic, not to mention cheaper, than, say, the more obvious Rome, Florence or Venice. I didn’t take into account just how difficult it is to get here. For once, I took my beloved trains with good reason and for much of the journey it felt like the wise decision. I sped to Paris, passed a relatively uneventful night on the train to Milan, and snoozed and read my way through a smooth and inexpensive express ride to Lecce. At which point, it all went a bit wrong. Despite or because of the copious advice from most of the inhabitants of Lecce, I spent nearly three hours covering the 25 miles or so to Otranto, as night and my spirits fell. Welcome to the South.

Otranto, on almost two days’ acquaintance, is pleasant, but – so far – it is hardly the kind of dirty, beautiful city that makes this woman’s heart beat faster. (Then again, there is only one Palermo…). It is very small, with a highly-touristed centre, all cobbled streets and no cars. The sea truly is turquoise, the castle is imposing, the cathedral striking, the gift shops full of expensive tat. As ever, my priorities have been to find bread, coffee and wine. There will be time enough for sight-seeing. At the bakers this morning, the woman recognised me, and we are already chatting, bonding over my crap Italian. (For the record, she thought I was German.). The contrast with Palermo is stark. There I spent fourteen weeks descending into Hades each morning – aka La Vucciria market. I never wore sandals, always watched each footstep, because the range of detritus from the previous night presented various threats to health. I knew it was a lottery as to whether the bakers would be open at eight thirty in the morning, and that it was a certainty that the young man serving (and I use the term loosely) would thrust the bread at me, mutter something incomprehensible, refuse to make eye contact, take my money and – sometimes – give me change. But the bread – oh the bread – warm, yielding, sprinkled with sesame seeds. Bread of heaven.

But back to Otranto. Franco, at the wine shop, was just as friendly as the bakery woman. He was keen to help me learn English but in fact, unwittingly, introduced me to a wonderful Italian phrase: ‘piano, piano’ which, if I understood it correctly, means take it easy, slow down, it’s ok, there’s no hurry – and all without the patronising sneer of ‘calm down dear’. Franco repeated this about a dozen times during the ten minutes I was in his shop. I suspect (it being Day One in a Strange Place) I was looking and acting somewhat stressed.

Still on my list of crucial things to do is to hire a bike. I had severe bike envy this morning, en route back from the bakers, and seeing the local cyclists gathering outside a café. It made me miss my own Oxford bike café, Zappi’s, but even more it made me want to get on to the roads of the Salento. I have also not yet found a bar in which to have my aperitivo. These things take time, and in the mean time I’ll just have to make do with the roof terrace here. As I write this, I am surrounded on all sides (my apartment straddles a narrow building, looking out over one street on one side, another street on the other) by the sounds of families enjoying a Sunday in Otranto. I like the buzz of noise, I like the breeze which blows through the rooms, I like knowing that a few steps will take me to the sea. It all helps counter my nerves about tomorrow morning’s opening class, but perhaps a couple of months in the Salento will teach me not only Italian but to take life piano, piano.

August 26, 2015

Jessie McCabe – this girl did

It took me decades of music making, after years of music education, to reach what I’ve called elsewhere – on Four Thought – my Morecambe and Wise moment (the moment when you ask yourself ‘Why are Eric and Ernie sharing a bed?’ and life is never the same again, there’s no way back to the days of innocence). I suddenly, and belatedly, realised that I had never played, sung or studied a single piece of classical music by a woman, and that I could count on the fingers of one hand the performances I had heard. Actually, one finger of one hand.

And now, here’s Jessie McCabe, aged seventeen, who, with the clarity (and effortless command of social media) of youth, is telling truth to power – specifically calling out the EdExcel exam board on their male-only syllabus.

Suddenly people (or rather people in the media) are talking about the issue, all thanks to Jessie McCabe. Do have a look at this piece by Caroline Criado-Perez in The Independent. She not only asked intelligent questions when she interviewed me, but listened to my answers. And just this morning, I cycled in the pouring rain up to Radio Oxford to do a live interview on the Today programme. You’ll find me and James Naughtie sandwiched between Greg Rutherford and the nine o’ clock news, so it’s all a bit rushed, but for a girl like me who was brought up without television and still doesn’t watch much of it (apart from the cycling), this is nearly as good as it gets. Nearly, because I can still dream of Private Passions on Radio 3…Michael Berkeley, hear my prayer.

As ever, as I cycled back down the Banbury Road, and as I slowly stopped shaking, I thought of all the things I should have said, or said more clearly. I regretted not speaking more about creativity against the odds, or about the hunger out there for women’s music (surely it’s not a coincidence that when Radio 3 listeners were asked which composer should feature in a listeners’ choice special edition of Composer of the Week, they chose Louise Farrenc?) or about how we can change the way we talk about women composers, which happened to be the subject of my most recent post. But most of all, I feel guilty and foolish at having singled out Fanny Hensel as the forgotten composer with most to offer us – but I hope the ghosts of Caccini and Strozzi, of Jacquet de la Guerre and Martines, of Boulanger and Maconchy will forgive me. (Clara Schumann can look after herself…)

This mini media frenzy – I should also mention that this very blog has been featured by WordPress – has slightly overshadowed the more mundane, but nevertheless, to me, thrilling moment when my book moved off my desk and into production. It now has definite publication dates (7 April 2016 in the UK, 12 May in the USA – careful readers will note that 1 April did indeed turn out to be a joke), a beautiful cover, more of which next time, and you can even now pre-order it on amazon. If you use amazon.

But the last word, today at least, should go to Fanny Hensel because, lying behind my appreciation of her exceptional talent as a composer is an appreciation of just how hard-won a victory it was for her to get her music published in the final years of her life, and how short-lived that victory would be.

The happiness that exudes from Hensel in 1846, four years after this portrait was commissioned by her family (who ensured that it contained absolutely no indication of her musical ability, whether as performer or composer) is infectious and inspiring. Here’s how I write about it, which includes, more importantly, what she has to say about finally moving out from the private to the public world.

The happiness that exudes from Hensel in 1846, four years after this portrait was commissioned by her family (who ensured that it contained absolutely no indication of her musical ability, whether as performer or composer) is infectious and inspiring. Here’s how I write about it, which includes, more importantly, what she has to say about finally moving out from the private to the public world.

when asked by publishers, Hensel compiled a list of her compositions which were still ‘floating around the world concealed.’ Three more collections headed for the presses. The year ended with the writing of a piano trio, conceived (as so many previous works had been) as a birthday present for a family member, in this case, her sister Rebecka. The Trio’s first movement begins in suppressed tension, and builds to a powerful close. The second movement runs seamlessly into the third, which is marked Lied, linking it clearly with Hensel’s earlier ‘Songs for piano.’ The writing for the piano is fascinating, giving great freedom to the performer whose part, in the final movement is marked ad libitum. As an album note puts it, the music ‘drives to a grand climax as the strings, once again set two octaves apart, soar high above the tremolandi piano, and the trio powers its way to a resounding close in D major.’ In her diary, in May 1846, Fanny Hensel wrote ‘I feel as if newly born.’

She was only too well aware how long this moment had taken to arrive: ‘I cannot deny that the joy in publishing my music has also elevated my positive mood. So far, touch wood, I have not had unpleasant experiences, and it is truly stimulating to experience this type of success first at an age by which it has usually ended for women, if indeed they ever experience it.’

The wonder is heightened by a sense of the time that has passed: ‘To be sure, when I consider that 10 years ago I thought it too late and now is the latest possible time, the situation seems rather ridiculous, as does my long-standing outrage at the idea of starting opus 1 in my old age.’ Fanny is, of course, being ironic about her ‘old age.’ She was only forty, and feeling good on it, noting in August 1846 that ‘the indescribable feeling of well-being, which I have had this entire summer, still continues.’

July 28, 2015

We need to talk about Fanny (Hensel)

I just downloaded another recording of Hensel’s solitary String Quartet (which remained in manuscript until the 1980s). It’s an exhilarating performance by the Quatuor Ebène, almost raw in its intensity compared to the one, by the Asasello Quartet, with which I’m more familiar.

I wanted to find out more about the Ebène quartet and their brave (yes, it is still brave to record women’s music, it still needs a defence, so we are reassured that the quartet is ‘worth hearing’ – phew, what a relief, I haven’t wasted nearly twenty minutes of my life on something worthless) decision to play Hensel. I wanted to know why a young, all-male quartet with quite an edgy image

chose to play this woman’s work.

And so began a miserable encounter with the language we continue to use when talking about female composers, language that patronises, dismisses, misrepresents, ignores, and always and ever ends up comparing a composer to her male counterparts. The composer becomes, implicitly, a (failed) contestant in a race that they were never invited to join in the first place. It’s all the more miserable because I can’t seem to crush my optimism, can’t quite stop myself from feeling thrilled when I find that the Ebène quartet won a BBC Music Magazine award for their interpretation of Hensel’s quartet – wow! mainstream! – that they were praised and rewarded as advocates of her music – wow! progress!

But then it all goes horribly wrong. This is from a website promoting the CD.

“Felix’s quartets speak with intimacy, but are not devoid of violent, stormy emotion,” says Ebène cellist Raphaël Merlin. Although Fanny’s sole contribution to the genre is lesser known and undoubtedly less accomplished than her brother’s, the group simply “fell in love with her string quartet” and with sublime, spirited playing made a compelling case for the rarely recorded work.

No, no, no. What does ‘undoubtedly less accomplished’ actually mean? No matter: whoever wrote this sees it as a given, and doesn’t need to justify it with any rational, let alone musically-based argument. Yes, the quartet is less well-known. Would it not be interesting to ask why that is? How that happened? But instead, we are simply encouraged to make the lazy causal jump from ‘less accomplished’ to ‘lesser known’.

I pressed on regardless, wanting to find out why the musicians ‘fell in love’ with Hensel’s Quartet. Gramophone Magazine spiced up the quest by praising, in April 2013, the Ebène for their ‘ full-on playing and lively engagement with the music’, noting that with every disc that they record ‘there’s the unmistakable sense that they have something to say and an urgent need to say it’.

So what did they want to say about Fanny Hensel’s quartet? I watched over thirteen minutes of video footage, which promotes the CD. It was fascinating to hear the four musicians talk about their art. But (oh, again, my idiotic optimism) not a word about Hensel. One player said ‘you have to respect the person who created the music’, but the video referred exclusively to ‘Mendelssohn’ (ie Felix). In a final kick in the teeth, the only female voice that is heard is off camera at the start of the film, and she is the recipient of what I am forced to call banter, including a final joke about the male players’ preventing her having an orgasm. It’s all here at no fanny hensel.

I kept looking. I found that the quote about falling in love with Hensel’s quartet was originally followed by the comment that she composed ‘with surprising freedom’. Great – but wouldn’t it be interesting to think about why you find it surprising? Alternatively, wouldn’t it be a sign of ‘respect’ for the composer to try to understand why certain kinds of ‘freedom’ were utterly denied to Hensel, as a composer, as a woman?

But, the bottom line is, I am grateful to the Ebène quartet for making this music live, and in awe of their ability to do so.

My real despair centres not on these screamingly obvious examples of sexist banter or patronizing dismissiveness. They are easy to spot, easy to call out. What is more insidious is well-meaning phrases like these, from Presto Classical’s review of the disk: Fanny ‘being a woman, was never in a position to build a career in the way that her brother had’. Her quartet ‘contains themes, ideas and moments every bit as good as anything from Felix’.

I know I should be grateful for this justification of the quality of Hensel’s music (she’s just as good as her brother), and for at least the acknowledgement that her chromosomes determined whether she could build a career. But there’s such passivity in the words. Fanny Hensel was ‘never in a position to build a career in the way that her brother had’ because time and time again, and in subtly powerful ways, over decades, she was stopped from doing so – by others. That she did at last – gloriously, courageously – ‘build a career’ in the final months of her life is, for me, one of the most moving struggles I have written about. Critics who do take Hensel’s music seriously cannot resist bringing Felix into the equation. They appreciate the ‘darker soundworld of Fanny Mendelssohn’s’ quartet’ (ie darker than Felix’s) or celebrate her work as ‘formally and harmonically, more daring than Felix’s’. Add to the mix the fact that Fanny is invariably known by her maiden name. Is this about reassuring people of her pedigree? Is it an attempt to trick naïve buyers into consuming women’s music, sweetening the bitter pill? Surely the composer deserves to be judged in her own right, rather than always placed in a sentence along with her brother, the same brother who – for reasons that made absolute sense to him, and much of the Mendelssohn family, together with much of elite Berlin society – worked tirelessly to ensure that she would have no ‘career’.

I need cheering up. You probably do too. So, in a narrative leap that makes complete sense to me, and might just make sense to you, here (thanks to ITV 4) is Marianne Vos, the greatest female cyclist of our era, responding to Anna van der Breggen’s victory in La Course. (For those of you who do not follow cycling, La Course is a step forward in women’s cycling. The women are allowed a couple of hours of racing before the men on the final day of three week Tour de France. It’s a start.)

http://www.itv.com/tourdefrance/2015-la-course-mariane-vos

Enjoy!

July 17, 2015

No more nuns with guns

With deep regret I have to report that Nuns with Guns 2 didn’t make the cut. I can’t think why a serious non-fiction publisher with a track record for thoughtful books about philosophy, religion and culture would walk away from it, but hey, what do I know? Then again, they also rejected Shadow of the Courtesan (not a bad title…you’re reading this, aren’t you?); La Musica (foreign language therefore bad); and Notes from the Silence (too clever by half).

Instead, my book about powerful, determined women creating great music against the odds is going to be called…

Sounds and Sweet Airs: the Forgotten Women of Classical Music

‘Sounds and sweet airs’ is a quote from Shakespeare’s last play, The Tempest, and it’s Caliban (offspring of a witch and the devil) who says the words. There’s a certain irony in a book about canon-busting creative women being given a title from The King of the Canon himself. There’s even more irony in the fact that it’s Caliban’s line: Caliban who is servant and slave, tamed and silenced – destroyed? – by his master Prospero; Caliban who is the child of ‘blue-eyed hag’ Sycorax, the powerful witch whose island Prospero has usurped.

For me, Sycorax represents precisely the image of powerful black-magic fueled creative womanhood that every single one of the female composers I write about had to fight against, in their world, in their own minds. She’s all the more toxic because we don’t see her on stage: she is an idea. Shakespeare’s Sycorax was first vilified on the London stage on 1 November 1611. Thirteen years and three months later, in the hills above Florence, Francesca Caccini offered her audience two witches, live and on stage: the attractive, sexy (but bad) Alcina and the equally attractive, bi-gender (and good) Melissa. Interesting, eh? (By the way, I’m extremely excited at the news that Caccini’s La Liberazione di Ruggiero, complete with witches and ‘sweet airs’, is going to be performed at the Brighton Early Music Festival in November: see http://www.bremf.org.uk/ which has the ominous phrase ‘subject to funding’ but I’m hopeful. In the meantime, you can see Christina Knackstedt as Alcina in Cornish Opera Theater’s 2011 production in Seattle here: La Liberazione.)

Having thrown my toys out of the pram, I’m now getting to like the title. Its choice sent me back to The Tempest, where I looked at the quotation in context. It comes in a scene in which uncivilised Caliban first encounters civilised European music – Stephano’s drunken singing – and in which the shipwrecked sailors are then terrified by the sound of Ariel’s magical music. It is Caliban, the monster, who reassures the men with words of beauty and power and sadness. (Shakespeare does this: gives lines like these to his monsters, Jews and Moors – before they are destroyed.)

Be not afeard; the isle is full of noises,

Sounds and sweet airs, that give delight and hurt not.

Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments

Will hum about mine ears, and sometime voices

That, if I then had waked after long sleep,

Will make me sleep again: and then, in dreaming,

The clouds methought would open and show riches

Ready to drop upon me that, when I waked,

I cried to dream again.

As ever with Shakespeare, ideas about music and dreams circle and encircle each other here, and one could spend a happy lifetime exploring Caliban’s words. But, for me, right now, and thinking specifically of my book, the idea of delight and hurt seem the most important. When I talk to people about what I’m doing, I sometimes hear the argument that, by paying belated attention to the music of female composers, I’m somehow diminishing men. (This is, of course, a familiar anti-feminist argument in many, many other contexts.) For every Caccini song played on the radio we lose a Mozart symphony. No: Caccini does not displace Mozart. She adds to our cultural riches. I want a world of Caccini and Mozart, Hensel and Beethoven, Maconchy and Shostakovich – delighting in the achievements of creative women does not, will not, hurt men.

July 7, 2015

Look closer. Look back.

The landscape you see here is that of the hills and mountains to the south of Sarajevo. Last month, I walked with a handful of young people, drawn to this beauty from faraway places like Brazil and Singapore. Benjamin, our guide, drove us to a village called Lukomir (Harbour of Peace), from where we walked, drinking in the clear air, to the edge of a precipitous gorge. Climbing back up to the village, we were fed delicious cheese pies and yogurt, looked at the centuries-old Muslim gravestones, filled our bottles from one of the many natural springs, before bumping back along an unmade road towards Sarajevo, down past the Olympic village of Bjelasnica. It was a very special day out. Despite the occasional passing comment from Benjamin (“that’s where the UN safe haven was, but how could people get to it?” “only one house was shelled in Lukomir – it was just too out of the way to matter”), and despite returning to still war-scarred Sarajevo with posters advertising, if that is the right word, a Srebrenica exhibition, posters that made me look away every time, it was almost impossible to imagine this idyllic, pastoral landscape desecrated by civil war, neighbour killing neighbour, these hills as launching points for mortar attacks. My daughters were born to the soundtrack of the Balkan wars. I would turn off the radio because I couldn’t bear to hear any more, as I held their new lives in my arms. God – or possibly a good therapist – knows why I am drawn to the region, but I am.

The landscape you see here is that of the hills and mountains to the south of Sarajevo. Last month, I walked with a handful of young people, drawn to this beauty from faraway places like Brazil and Singapore. Benjamin, our guide, drove us to a village called Lukomir (Harbour of Peace), from where we walked, drinking in the clear air, to the edge of a precipitous gorge. Climbing back up to the village, we were fed delicious cheese pies and yogurt, looked at the centuries-old Muslim gravestones, filled our bottles from one of the many natural springs, before bumping back along an unmade road towards Sarajevo, down past the Olympic village of Bjelasnica. It was a very special day out. Despite the occasional passing comment from Benjamin (“that’s where the UN safe haven was, but how could people get to it?” “only one house was shelled in Lukomir – it was just too out of the way to matter”), and despite returning to still war-scarred Sarajevo with posters advertising, if that is the right word, a Srebrenica exhibition, posters that made me look away every time, it was almost impossible to imagine this idyllic, pastoral landscape desecrated by civil war, neighbour killing neighbour, these hills as launching points for mortar attacks. My daughters were born to the soundtrack of the Balkan wars. I would turn off the radio because I couldn’t bear to hear any more, as I held their new lives in my arms. God – or possibly a good therapist – knows why I am drawn to the region, but I am.

This was going to be a post about women composers and war (and peace) – and that post will be written, because there is an important story to be told, some fascinating patterns to be revealed – but right now, Bosnia is still with me, perhaps because last night one of the disconcertingly talented Oxford Creative Writing students (Dunja Janjic, twenty years ago a child in exile from Sarajevo, like my guide Benjamin) brought me to tears – and laughter – with a story about her toddler self. You can find out more about the adult Dunja, and indeed her fellow students, at http://www.writeoffarena.com/#!authors/c1875).

Back in the meadows below Lukomir, Pedro, from Rio, and also a child at the time of the conflict that sent Dunja and Benjamin into exile, said what many are now saying – Bosnia is a welcoming, hospitable country precisely because of the horrors. Sarajevo, with its café culture, is now a cool weekend destination: Bosnia a ‘vibrant’ addition to tired European itineraries. Sarajevo is the Jerusalem of Europe, says the Pope who arrived the week before me and prayed for peace, although there is little obviously spiritual about the shiny new banks and shopping malls, there to serve…whom? Certainly not the ordinary Bosnian, living on an average salary of just over 400 euros a month.

Sarajevo is fashionable despite, and because, of its traumatic recent history, war tourism one of its most bankable assets. I’ve always been sceptical about war tourism: it took me years before I went to visit Terezin, where my own grandmother was imprisoned (she would die in Treblinka), and I’m not sure it helped heal any wounds, although it did convince me once and for all not only of the banality of evil, but the ease at which it can be achieved. My scepticism is derived, I think, not merely from the way a certain kind of war story is foundational to the grand, high-political, male-centred narrative of history, but the way in which some forms of war tourism can turn human misery into an exhibit, make us voyeurs, and thus put the past, and the human beings who lived that past, at a safe distance, from me, from us, here and now.

Back home, a few days after my return from the Balkans, I was cycling through the Cotswolds on a quintessentially English summer’s day and, descending a winding, minor road was confronted with that most thrilling of things – a ford. I stopped to take a photograph, and spotted a notice board which informed me that this was ‘Traitor’s Ford’, so called because it was one of the back routes to the battlefields of England’s civil war: Edgehill – 23 October 1642 – was not far away, in space if not in time. I read that the local villages endured ‘groups of soldiers plundering food, goods, horses, cattle and sheep without payment’. If I hadn’t read the rather battered notice, then the only clue in this quiet country lane, as idyllic in its own way as the hills above Sarajevo, would have been the name, Traitor’s Ford. I had stumbled into war tourism in my own back yard – and it was just as hard to imagine the horrors of war here as it had been in the highland meadows of Bosnia.

Back home, a few days after my return from the Balkans, I was cycling through the Cotswolds on a quintessentially English summer’s day and, descending a winding, minor road was confronted with that most thrilling of things – a ford. I stopped to take a photograph, and spotted a notice board which informed me that this was ‘Traitor’s Ford’, so called because it was one of the back routes to the battlefields of England’s civil war: Edgehill – 23 October 1642 – was not far away, in space if not in time. I read that the local villages endured ‘groups of soldiers plundering food, goods, horses, cattle and sheep without payment’. If I hadn’t read the rather battered notice, then the only clue in this quiet country lane, as idyllic in its own way as the hills above Sarajevo, would have been the name, Traitor’s Ford. I had stumbled into war tourism in my own back yard – and it was just as hard to imagine the horrors of war here as it had been in the highland meadows of Bosnia.

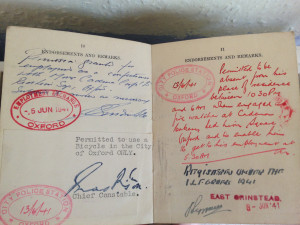

Sometimes – and I suppose this is one of the things that keeps me going as a biographer – it is the little things that reveal a life and a time, that provide the connection between the living and the dead, between now and then. A few days ago, I found some documents connected with my father’s arrival in this country. It was 1939 and he, like Dunja and Benjamin, was a refugee from war and ethnic cleansing. Unlike them, he was almost a man – seventeen years old – but, unlike them, he would never, could never, return to the country of his birth, Czechoslovakia. Amongst the fragile papers was a robust booklet, his Certificate of Registration as an Alien. Each month he reported to the police, who duly tracked his movements across the south of England. On 5 June 1941, almost two years after his arrival, my father – who would have just turned nineteen – was granted permission to be employed as a ‘confectioner’ at the Cadena Café, Red Lion Square, Oxford. Eight days later, in a rare type-written entry, he was granted permission ‘to use a Bicycle in the City of Oxford ONLY.’

My father would remain in Oxford for just a few months. By mid-July 1941 he was in East Sussex at a school called Fonthill Lodge, where his fortunes would change dramatically. This little book reeks of wartime, of a life under constant surveillance, of moving relentlessly from one precarious lodging to another, of nights spent fire watching, of exile, of being an ‘alien’ – a life I have never known, and that i can barely imagine – but it also connects me powerfully with my Dad, who cycled through the streets of Oxford, just as I do now.

March 26, 2014

West is best

I am rereading Rebecca West's Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: a Journey through Yugoslavia. Despite being only up to Macedonia and page 688 (of 1150), I do not want it to end. West may be absolutely of her time (the book was published in 1942, and is a desperate cry for liberal, humanist values at a time when those values were being annihilated), and Black Lamb may be an unashamed love song to the Slav peoples, and in particular the Serbs, but West and her writing are never trapped in the past, never merely partisan.

I must admit that I am sometimes appalled by West's assumptions (about homosexuality, for example), or her apparently simplistic judgements on whole nations or religions: Germans are bad, Serbs are good; Roman Catholicism is bad, the Orthodox Church is good. Yet although I do not share her view of men and women's essential natures (compare Martians and Venusians for a more recent, and much more crass, formulation of the idea), I have rarely read a more elegant dissection of family life as West's observation of an Orthodox religious rite:

Crying shame: the books that make me weep

God bless us, one and all! The Muppets' take on Tiny Tim and Bob Cratchit. Photograph: Kobal

One of the many reasons that I would not last long in a reading group is that I get far too emotionally involved in the books I read. In fact, I am prone to cry at the slightest provocation. I am not just talking about the kind of tears most people would shed on reading, say, King Lear or Toni Morrison's Beloved.

I have sobbed my way through Mrs Dalloway (and not just the Septimus bits), Bleak House (Jo saying the Lord's Prayer...sentimental, yes, but give me another tissue) and The Handmaid's Tale. I cry at Anne Tyler, Carol Shields, and even Walter Moseley. And on holiday in 2005 I sobbed through Joanne Harris's Blackberry, which does not make me proud.

Be a book borrower - but beware a lender being

Watch out who gets their hands on your library

Mr Heber, a Victorian chap, claimed that a gentleman needs at least three copies of each book: a show copy for one's country house, a copy for one's own use and reference, and a third "at the service of his friends". I am not a gentleman, I don't have a country house, and I don't have triplicate copies of every book I own, but Mr Heber has a point.

When characters breathe their last

I have been thoroughly enjoying this site's discussion of great opening lines. Thinking about first lines made me think about great closing lines - and then about the great "last words" of fictional characters.

Which got me thinking about tragedy, and reminded me why I left the execrable Stratford production of King Lear at the interval. I don't usually walk out on plays, and I have nothing against Sir Ian McKellen taking his clothes off, but I was dismayed by a couple of hours of theatre where potentially moving and profoundly serious moments were, lazily, played for Carry On laughs

Blackadder was only half right about Ralegh

A hero with a dark side ... the statue of Sir Walter Ralegh outside the UK's Ministry of Defence. Photograph: Martin Godwin

On Radio 4 this summer, Andrew Marr has been keen to elucidate Englishness by looking at individually famous English people. One week it was Miss Marple, the next it was Sir Walter Ralegh (which, by the way, is the spelling of his surname he eventually plumped for after trying out a range of variations - though he never spelled it as 'Raleigh')... Having spent the best part of my adult life slavishly devoted to the latter, I turned on the wireless with great interest.