Conrad Williams's Blog, page 9

December 4, 2015

Advent Stories #4

CRAPPY RUBSNIFF

Stanniford was waiting for them when they got back. He watched the two men enter the room and help themselves to drinks from his cabinet. They settled into a pair of leatherette armchairs on the other side of Stanniford’s desk. Soon, the only sound was that of the traffic on the main road and the ice chinking in their glasses. They seemed relaxed, but Haslam was looking anywhere but at him and Tasker couldn’t get his drink down fast enough. Stanniford left it a little longer. The drink wasn’t doing what it said on the label. Haslam started to squawk.

‘I think…’ he said. ‘I think…’

‘Charlie,’ Stanniford said. ‘That is something you manifestly do not do. I think. You listen. And act. Or you’re supposed to.’

‘I think…’ Haslam began again.

‘You think, therefore you’re a cunt,’ Stanniford said. He left him to it, slowly rolled his eyes Tasker’s way. Tasker was busy refilling his glass. His face was pinched hard and greying, as if someone had coated it with quick-drying cement. ‘What’s Descartes here trying to say, Phil?’

Tasker took a mouthful of whisky and swiped at some invisible hairs on his jacket. ‘He got away, John.’

‘You. Fucking. What?’

‘I think he did. It was hard to see. Dark. Lots of smoke. But I saw… we saw a shape coming out the back window.

‘Well now,’ Stanniford said. He caught a glimpse of himself in the waxing blackness of the window, a pallid man who had lost too much weight too quickly and resembled something ill-packed. His skin was baggy, as was the black Dior Homme wool suit, which had once looked so very sharp on him. The light was such that he was unable to see anything of his eyes beneath the heavy ledge of his brow, just a couple of wedges of shade above a hawkish nose and the humourless slit of his mouth. ‘Well now. What’s it come to? I can’t rely on my best men to do a job for me? Did you follow him?’

Haslam found his voice. ‘We followed him.’

‘But you lost him.’ Stanniford favoured the younger man with the kind of tones one might use with a child.

Tasker put down his glass and got to his feet. ‘We lost him, but there aren’t that many places he can go. We’ve shut the door on most of his people. Give us a little more time and we’ll flush him out.’

Stanniford sucked his top lip between his teeth. He had no choice, but he didn’t like conceding to an employee’s suggestions. ‘Fix me a drink,’ he said, flatly, not wanting one, but needing to lord it. ‘Vodka. Plenty of ice.’

Tasker handed him the glass but Stanniford took his time before accepting it, keeping his eyes on him, keeping the shadows there so the other man wouldn’t be able to read him.

‘You bring me Kelleher’s face in a paper bag before this time tomorrow night,’ he said, the ice chinking against the expensive crystal, ‘or I will have your arse for a fucking ink well.’

*

What had he lost? Really lost, in the grand scheme of things? A couple of secondhand paperbacks from the Scope shop down the road; a half-litre bottle of the cheapest white rum he could find; a batch of letters from Fran; his mobile phone. That was all. Losing the letters hurt most, of course, and he didn’t feel too great about grabbing the gun instead of the bundle before removing his arse from the flat. But Fran was dead and what she didn’t know couldn’t bring her back from the grave.

At least he had got one of the fuckers before they came for him. And it was good, really, that he hadn’t died. He’d have the rest of his lifetime to wish he had. They’d know how dangerous he could be. How far he was prepared to go. They’d be scared of him, a little. Maybe more.

Kelleher hadn’t stopped running for ten minutes, but now he ducked into the driveway of a house in Lordship Road to catch his breath and try to work out what to do next. The driveway was blocked, but not by anything so grand as a car. He couldn’t remember the last time he had seen a car in a driveway, certainly not in London. Driveways were for skips or rotting mattresses, or, in this case, an old GEC cooker and half a dozen swollen, ripped bin bags. He sat down with his back against the cooker, trying not to displace the spilled tin cans and beer bottles too much. It was getting on for 2 am. A change in the wind brought back to him the swoop of the sirens from Amhurst Park. His clothes — thankfully he’d fallen asleep fully dressed — smelled of smoke and part of the sole of one of his Pro Keds had melted in the heat. What had they used back there? Had they doused the whole building in petrol? The place had gone up quicker than Argentinian inflation.

Kelleher checked his gun. A virgin clip, but his last. He’d need to find fresh ammo before dawn. The gun was a battered old thing, a 9 mm Glock 17 that felt too light and plasticky to give him any real confidence, but it was all he had, stolen from the safe of a Korean restaurant he’d burgled in Manchester the previous summer. He hated guns; if you had a gun, you were much more likely to get shot, but the stakes were so high in the city now. Everyone who was a player had a piece. If you didn’t… well, you weren’t a player. Simple as that.

He found himself wondering more and more about that these days. Not being a player. Losing the gun, losing himself. Maybe get out of N16 and drive north, don’t stop till the petrol runs out. Ditch the car, get a job in a bar, find some new walls and a roof, a woman to help forget himself for a while. It sounded so easy, but he couldn’t do it, not yet, not while the sound of Fran’s breath as it gurgled out of her body still swam around in his head.

It was cold, now that he had stopped running. Stopped running. Now there was a joke. If it wasn’t for the fact that he was such a considerate neighbour, he’d have sat there hooting his Jacob’s off at the hilarity of it all. Instead, he closed his eyes and tried to think of an open door, or at least a door that was slightly ajar, offering a chink of light, some warmth. Everyone he knew in the city had been scared off, or had disappeared. And so should he, but for what had happened to Fran. He couldn’t leave until he’d sorted that out.

He caught a night bus to Lewisham, a nightmare of a journey that involved a change at Trafalgar Square where he had to wait for 20 minutes for a connection. The driver woke him up with a nudge at a little before 3.30 am; the bus was parked in the terminus. He thanked him and stepped off, depressed by the oily quality of the dark. He walked the half mile or so to Hither Green Lane and took a right, stopping by the disused St George’s hospital, which was hunkered down in black shadows, its windows boarded up, looking like anything other than a place where you could go for help. Every building, though, looked like that to Kelleher now.

He forced himself to wait for five minutes. Every window in the street opposite he checked for movement. He clocked every car that trundled by and listened hard for footsteps, sniffed the air for the smell of cigarette smoke. All clear.

He paused again outside the flat on Lullingstone Lane and had one more check of the area around him: the residential parking bays and the high wooden fence on to the dead hospital’s grounds. The windows visible in St George’s were either boarded over, punched out or milky with smears. It seemed to suck the silence into itself, becoming ever more still and dark with each passing second. He knew, if he didn’t act, that he would become the same before long. Already he could feel vast corridors of emptiness reaching out inside him, offering him miles of darkness to walk alone.

He knocked on the door.

*

‘You fucking prick,’ Tasker said again. He regarded his partner, who was looking out through the passenger window, his elbow up against the door, busy with whatever feeble thoughts buzzed around that colossal head of his. Haslam wasn’t rising to his bait.

Not for the first time, Tasker wished that Nicky Preece had been able to last the pace. It would be good to have Nicky around now, inasmuch as any endgame could be described as being good. But he’d feel more confident with Preece, instead of this hair-trigger arsehole. Where the hell had Stanniford picked him up from? Tasker squeezed the steering wheel tight for a few seconds, until his knuckles whitened under the sodium lights streaming past the car as they nosed through Holborn. Nicky Preece was on a ventilator now at the Royal Free. Half of his chest had been blown away, and a leg too, one morning two weeks ago when he started his Mazda up outside his gaff in King’s Cross and found out, too late, that the engine had been souped up with something extra special. The day after, Tasker had rented a lock-up for his own motor. The day after that, Stanniford introduced him to Haslam.

He thought back to that evening. They’d met in the World’s End in Finsbury Park, a large pub with a purpose built stage for gigs and karaoke. Stanniford and Haslam were there waiting for them. Two pints of Stella sweating hard on the table. Nothing for Stanniford if the pub didn’t serve Finlandia. Tasker didn’t like the look of the other guy from the off. His muscles were gym muscles. He wore a goatee, one of those jobs that looked like he’d dribbled treacle from his bottom lip to his chin. And he looked around him nervously, fiddled with the buttons of his Paul Smith suit, licked and re-licked his mouth as if it was a fucking lollipop.

Stanniford, Mr Economy: ‘This is your new partner. No buts.’ And he was gone, leaving them to their pints like two desperates on a blind date.

Since then, their hunting of Kelleher had not gone as well as Tasker would have liked. This was partly down to Kelleher’s savvy, and refusal to stay in one place for longer than a night, but it was also because Haslam was making his shit hang sideways. Tasker couldn’t focus. Every time he felt he was drawing a bead on the situation, Haslam would say something to knock him out of whack. He was getting sick of it. If Stanniford refused to notice that Haslam was an issue, a fucking liability, then they could both piss off and play house together. There were other places he could work. At his age, he didn’t need the aggro.

‘What’s left?’ he asked now.

Haslam looked at him as if he’d just suggested they have sex with a couple of rats. He sat up in his seat and looked out as they swung on to Waterloo Bridge. It was raining.

‘Left is St Paul’s, the Barbican, Canary Wharf and — ’

‘Fucking hilarious,’ Tasker spat. ‘Answer the fucking question or you’ll be left too. Left on the fucking bridge. As fucking roadkill.’

He chewed his teeth while Haslam took his time opening the A-Z. Haslam said, ‘Swearing indicates a limited vocabulary, you know.’

‘Answering back to me indicates a limited intelligence,’ Tasker said. ‘Especially in this fucking car.’ Just push it, he thought, just fucking push it a little more and I’ll air some fucking grievances. And then I’ll air you, you scum-sucking piece of shit.

‘We’ve got a shit-pit off the Old Kent Road and that’s it. If he isn’t there, then he’s scooted. We’ll never find him.’

‘You lose this cocksure attitude in front of Stanniford, don’t you? You piss yourself.’

‘I don’t piss myself,’ Haslam said, his voice hard and flat. ‘I play Stanniford like a fish. He wants to see people intimidated in front of him. I tell you something. He’s more comfortable with me than he is with you. He isn’t sure about you.’

‘I’ve known John Stanniford twelve years,’ Tasker said, slowly, making sure he took it in.

‘Counts for nothing,’ Haslam said breezily. ‘He thinks you’re after his crown.’

Tasker’s fingernails had found the soft area at the base of his palms and were digging. He reined it all in and eased back in his seat. Brought the needle down from 45 to 35. There would be time, at the end of all this, to let his steam escape. And then —

He pulled up around the corner from the Dun Cow Surgery and got out without waiting to see what Haslam might say. His back to the main street he dipped his head into the flaps of his greatcoat and checked the chamber of his customised Brocock, then motioned for Haslam to follow. It had been Haslam’s idea to torch Kelleher’s flat and it was the first and last time he went with any of the smaller man’s dumbfuck ideas.

‘You stand in my shadow for this one,’ he warned Haslam as they moved into the target street.

‘Stanniford has us equals in this job.’

‘Yeah, well I’m not Stanniford and I’m telling you to fuck off. Watch our backs. You can cry your heart out to Stanniford later.’ He could feel Haslam tightening up behind him like the coil in an overwound watch. Once they reached the stairwell of the block of flats, however, he pushed Haslam out of his mind. As long as he did his job properly, he wouldn’t have to think of him again until they got back on the street.

But it didn’t work out like that. On the target corridor, Haslam was pumped up so much that he started kicking doors in. He’d done for three when Tasker decked him with a punch to his stomach. He swung around as babies’ screams and yells of consternation came from the adjoining flats.

He waited until the testosterone was coming at him from the doorways and then he showed them his gun. ‘Go back inside,’ he said, and they did, all good boys.

A little further along, Tasker rang a doorbell and a woman answered. He pushed her back into her flat, ignoring the strident demands as to who he was, and pressed the muzzle of the gun against her sternum. He smelled piss, very strong, as her bladder gave way. ‘You should drink more water,’ he said. Her mouth was doing the beached fish. She had nice eyes, but her skin was very tired, her hair so used to colour from a bottle that it was the consistency of straw. ‘I won’t harm you,’ he whispered, conscious of the clock ticking. ‘But if Kelleher is here, if you’re hiding him, give him to me now.’

*

It was difficult to lock down the precise moment that his London life had begun to fall apart. Fran’s death codified it, made it all super-real, but the spark that lit the kindling? If he wanted to be extra anal, he could go all the way back to the day he joined the gym, in his mid-teens, and started making all the connections his parents begged him not to make. But the stuff that was happening now could really only be measured from the date of the cricket match, two summers back, at a nice little ground in Herne Hill. A casual game set up by some friends of his, an excuse to get the barbecue out and order half a dozen cases of lager. Invite plenty of ladies along and hope the sun was strong enough to get them dressing in bikini tops and quim skimmers. It was an in for him. He met a few men who were intelligent enough to know that muscle was no good unless there was a brain on top of it all. One guy had impressed him more than the rest. It helped that they struck up a partnership with the bat out at the crease. Kelleher reached 74, the other man 88 — they’d put on 62 since the previous wicket had fallen — before Kelleher was caught, slashing at a ball on the off side. As he trooped off the pitch, the other man had shook his hand and invited him for a drink later. Yes, he had impressed Kelleher, but his mistress had impressed him more.

— I’m Frances, she had said when the game had been won. Stanny’s not stopped talking about you.

— I’m Frances, she had said when the game had been won. Stanny’s not stopped talking about you.

— Who’s Stanny? he asked, thinking I could care less, and wondering how much curve a man could take before he went raving mad.

— My man. Your partner out there. John Stanniford.

He’d turned up then, fresh from the shower, his gaunt face coloured in by the jets, his suit fitting him so well it looked as if it was something to be shed, rather than taken off.

— Great knock, Stanniford said, offering his hand again. Again, Kelleher took it.

— Great century. You carried your bat like a pro.

— Thanks, Stanniford said. Let me get you a drink.

Frances arched her eyebrows as Stanniford went over to the cooler chests and picked out three bottles of beer. — He never gets his own drinks, she got off, before he was back within earshot.

— You here with anyone I know? Stanniford asked him.

— Not really, just those clowns over there, the guys set the match up.

— Nice blokes. You work with them?

— No, Kelleher had said, pointedly, fixing Stanniford with a look, with a come on.

— You looking for work?

— Yes.

— Well, Stanniford said, knocking back the rest of his bottle and looking at his watch, best of luck. Hope you get some.

Then he was moving away and Frances was going with him, but not before looking back over her shoulder and tipping him a slow wink that he knew he’d carry into his dreams that night. He watched the silver Porsche Boxster swoop out of the car park and rebuffed all other parties, for the rest of the afternoon, evening and night, knowing that something was going to happen there.

And Christ, did it ever.

*

Stanniford suggested Marylebone Library because of its proximity to Paddington Police Station and because it had a security guard, which would make the punters more relaxed and unsuspecting. As an added bonus it was within spitting distance of the Westway, a quick out of the Smoke. And because, who’d have thought it? A fucking library.

It was all news that calmed their nerves. They said, we like it. We like it a lot.

The exchange: a hundred DVDs, no packaging, no labelling, zipped up in a Case Logic disc holder — teen-porn, smuggled in from the Hook of Holland that very morning — in return for a dozen handguns skimmed off the amnesty stockpile, courtesy of their PC Bentboy.

Stanniford was in a suite at the Landmark Hotel across the road, watching it all play out with a pair of Zeiss in one hand and a Finlandia with a fistful of cracked ice in the other. Frances lying on the sheets behind him, naked, smelling good, waiting for him to finish his drink.

The kicker: an hour before swapsies, the security guard had been taken out by Kelleher who was now sitting in the booth in a white shirt and clip-on tie, reading a copy of GQ and stroking the baseball bat at his side. Waiting to do some good work for his new boss.

Stanniford’s men came in a two minutes to eleven. Kelleher nodded at them: Tasker and Preece, good men. He watched them, Tasker carrying the disc holder, as they moved through the swing doors, past the reception desk and over to the travel section, back left of the library.

Five minutes later, and three minutes late, two more men entered the library, both of them uglier than something dreamed up by Grimm. One of them had a green North Face rucksack slung over his arm. Kelleher avoided eye contact. It was better that way.

He watched them move towards the music section back right of the library, where the CD shelves stood. He was distracted by someone knocking insistently on the booth window, but only for a second, till he realised it was his heart beating. Beating like it had the first time he and Frances fucked against the wall in Stanniford’s garage, a wild two-minute thrash in the middle of an evening’s entertaining at Stanniford’s pile out in Egham.

Keep those visuals, he thought, as he lifted the bat and edged out of the booth. Five past, now. A quick peek. The swap made. No trouble. Two men disappearing out through the swing doors at the back of the library, heading for the fire exit. Two men coming his way, making for the main doors.

Fran sucking hard on his ear as he went for it, sliding her hand up his back, her breasts scooped out over her Wonderbra, jiggling against his chest. The warmth of her, the unbelievable heat. He felt her heartbeat, an insistent code of need drumming through to him.

— Morning, ladies, he said, as the doors swung open. He clipped Preece across the jaw, which broke immediately, and he went down in a squealing heap, trying to keep his mouth where it was meant to be. Tasker he felled with a sharp swipe to a kneecap. The sound as it popped made him feel ill. Tasker too, by the look of his face: it filled with grey, the eyes rolling back in their sockets as if he was auditioning for something by George Romero. Kelleher gave Tasker another to the side of the head, to keep him down, and kicked Preece in the balls when it looked as if he was trying to get his hand in his pocket. Then he dropped the bat, picked up the rucksack and left, eyeballing nobody till he was in the Merc with the ugly sisters and screeching away along Upper Montagu Street.

In the back, he punched Fran’s number into his mobile.

— Kelleher. You fucking cunt.

He was about to hit the call end button but Stanniford wasn’t finished. Kelleher didn’t like this. Stanniford never picked up Fran’s calls. Not in the month since they’d been seeing each other, anway.

— This is how you treat someone who was never anything but polite with you?

Kelleher forced himself to remain civil. — I could have been good for you, he said. I was willing to be loyal. A good worker.

— I don’t need any more men, Stanniford said. And those that I’ve got are top professionals, worth any number of you.

— Yeah, well, you might want to come down to the entrance hall and help your top professionals to pick their teeth up off the fucking floor.’

— I’ m impressed, Stanniford said, in a voice that was anything but. Incidentally, I’ve put a stop to your covert shafting, what you thought was your covert shafting, of my bird. It’s all over. The end. She’s here on my hotel bed, room 27 at the Landmark, looking mighty fine, waiting for me to give her some attention. But I’m not in the mood now. I’ve already given her more than enough attention to last however many seconds are left of her lifetime.

Stanniford killed the link then, and Kelleher felt his mouth turn to dust.

— Go back, he said to Blondell, the ugliest driver in the world.

— Are you fucking nuts? asked Gearing, the ugliest passenger.

Kelleher opened the back door, the Merc doing 50 south along Baker Street.

Blondell, then: — Okay, okay, Jee-sus.

At the Landmark, Kelleher barged through the protests in reception and was about to shoulder down the door to room 27 when he saw that he didn’t need to. It was ajar. Seeing that crushed him. If the door had been locked, maybe he could have at least felt that he might have a chance to save her. But a door that was swinging on its hinges was the saddest sign in the world. He opened it anyway. The message Stanniford had left for him had been daubed on the wall in the stuff that had turned hot for him, been pushed around her body by the sweet tempo of her heart. You’d have thought he’d have the decency to spell his fucking name right.

*

Stanniford alone in the rooms above the cab firms, bookmakers and newsagents and endless, streaming traffic. Blackstock Road was doing an impression of a car production line at down tools. The Seven Sisters Road too was nose-to-tail, filling the air with exhaust fumes, impatient horns, blasphemy.

It was only 6 pm, but already the sky was midnight black. North London seemed at its happiest in the dark, as if it were in league with this colour, and revealed its best side. Stanniford watched the army of Arsenal supporters as they downed pints outside the The Twelve Pins or bought burgers and hot dogs from the portable listeria vans parked around Station Place. Some big game at the Emirates, some European night. A clash of the titans, no doubt. They don’t get much bigger than this.

The gun in the drawer was still there when he went to check it for the fourth or fifth time since daylight faded. He had loaded it himself that afternoon but couldn’t decide whether to keep the drawer closed or open. Maybe he should keep the piece in his pocket, but that would only spoil the lines of his suit, and a sharply-dressed man always had an edge over his opposition, even before guns came into the equation.

He poured a drink, a strong one, and took it back in one gulp. It had been such a long time since he’d been at the brink, stoked up to take a life. That was what his men were for, that was what being at this level was about. He didn’t have to do it anymore. He had paid his dues and passed the tests. He’d put the hours in over the years. Blood and fear were a young man’s game. Now he pulled strings and sent men to swap bullets or blades in order to gain ascendency and improve his territorial claims. Pity this this team of men were the most incapable bunch he’d assembled in his puff. He’d lost the nous that had served him so well in recent years when it came to judging character, it seemed. He should have brought in Kelleher at the start, despite his swagger, because of his swagger. Despite his transparent hots for Frances. What did it matter if he was boning her behind his back? He was only doing what he did himself every now and then. Did respect come into it? Was he really so up his own arse as to think that respect meant shit in this day and age? As long as he did the work, what did anything matter?

Well now it was too late. He knew that Tasker and Haslam would fail to hunt down Kelleher. Tasker was too full of resentment to be truly effective anymore and Haslam wasn’t so much the loaded gun he’d hoped for but a loose cannon. They’d had long enough. He knew too, and in this sense his hunches had not deserted him, that Kelleher would not fail to track him down. He was that kind of man, the kind that bears a grudge.

Stanniford stopped himself from reaching for the bottle again. And looking out of the window was the only way to prevent him from imagining the colour of his own death splashed all over the walls.

*

‘I don’t want you here,’ he said again. It seemed as though he had said nothing but in the half hour since Kelleher muscled by him into the living room.

‘It’s okay, it’s safe,’ Kelleher assured him. ‘I wouldn’t come here if I was drawing any heat, would I?’

‘How do I know that?’ he said. ‘How do you know that?’

‘I was careful.’

‘You? You’ve never been careful.’

Kelleher sat down finally, in the hope it might relax the older man. ‘I’ve learned how,’ he said. ‘I’ve been practising. Now Paul, please, relax. Got anything to drink?’

Paul spent longer in the kitchen than retrieving a couple of cans of Stella might have warranted, but Kelleher let it go. When he came back, and passed him his beer, Kelleher noticed the dilation of his pupils, and the dusting of white on his lips, but it was worth it to have Paul tucked up into a cosy manageability. Paul mouthed his can and asked if he had any cigarettes.

‘I don’t smoke,’ said Kelleher. ‘You know that.’

‘I’ve heard nothing but bad things about you, Rory,’ Paul said. ‘You’ve got some fucking nerve coming out here. I don’t want to get a caning for putting a roof over your head.’

‘They don’t know about you,’ Kelleher assured him. ‘You and Ally separated five years ago, for God’s sake. I haven’t talked to you for six. You might as well be some door I knocked on at random, hoping to find a good Samaritan open up.’

‘How come I get so much news about you then? How come?’

‘You haven’t heard any news,’ Kelleher said. ‘You’re playing safe with all that talk. But fair play, all that talk is still the right talk.’

‘See? You’re still fucking about. Still trying to play Goodfellas. You’ll get yourself killed. And me while you’re at it.’

‘Nobody knows about you,’ Kelleher said again, wishing he’d never had the idea to come down this way. But where else? Ally, his sister, was now overseas, living in Tuscany with friends she’d met at University. There was nobody else. Apart from Lucy, his aunt in SE15, but she wasn’t answering her phone. By choice, he hoped.

‘I didn’t want to come here,’ Kelleher said. ‘You think I want to come to the place where my sister took some beatings? The only time I thought I’d ever come here is to give you a fucking going over.’

‘So why are you here then?’ Whatever Paul had snorted was beginning to wear off already. A tiny thread of blood was creeping out of his left nostril. The rest of the flat was pale in comparison to this gentling of hard colour. Ally was still here, in many ways. Kelleher wasn’t certain that he could smell her perfume, but in the decor and the organised chaos her presence was acutely felt, to the extent that he thought she might roll in from the kitchen before too long, a joint smouldering between her fingers, to ask him if he wanted a plate of chips, or one of her fearsome Bloody Marys.

‘Some guys are trying to kill me.’

The line, like something cribbed from a Hollywood film, hung limply in the south London flat, like a deflated birthday balloon sellotaped to the ceiling that nobody can be bothered to retrieve. Paul didn’t even dignify it with a response for the time being. He sank the remains of his beer and went off for a couple more. When he came back the blood on his mouth had been smeared away, turned into an angry comma on his towelling bathrobe.

‘You can stay here tonight,’ he said, as if Kelleher had any intention of leaving if he deigned it. ‘But tomorrow you fuck off. I don’t want my life knackered because of you.’

As he left the room, Kelleher couldn’t resist it: ‘Words you’ve heard before, I’ll bet,’ he said. The door might have paused a fraction, in its shutting, but Paul didn’t come back.

He didn’t sleep. His confidence that he had not been followed was minutely chiselled away by the dark until every creak became the footstep of a man intent on snuffing him out. He wanted to get up and look through Ally’s things. He wanted to spit in Paul’s face and beat the shit out of him. He wanted Stanniford. He wanted to do to Stanniford what he had leisurely done to Fran, while Kelleher was sitting on his arse leafing through pre-pubescent magazines, getting a hard-on about how he was going to make the old cunt rue the fact that Kelleher had been rejected.

Uninvited memories of Fran kissing him hungrily, removing her knickers in the back of his car, he quelled by summoning thoughts of Ally. He had not spoken to Ally for almost as long as he had blanked Paul. She had been Paul’s apologist, even when her husband broke her collarbone, and Kelleher had given up hope of drumming sense into her dope-addled mind. When the only words you speak to your sister are warnings and those words are being ignored, it doesn’t come as a shock to you to find that you no longer communicate, when of course, it should do.

Kelleher rolled over on the sofa and closed his eyes. He and Ally sitting on a slight incline in Finsbury Park, right in the bullseye of summer, aged what — ten, eleven? — and he’s trying to nick what’s left of her ice cream after finishing hers. ‘Fossip!’ she yells at him.

‘What the bloody hell?’ he says. Around them, people are strewn in the grass like human litter, smoking weed, drinking cider from bottles, listening to cricket on the radio.

‘Fossip,’ she says again, more casually, licking at her 99. ‘Collip. Dipoots collip.’

He’s looking at her blankly, more, in an almost panicked way. It’s as if his speech has suddenly become redundant, as if everyone else has graduated to a new level of communication but forgotten to tell him what the new frequency is.

‘Ally, what — ?’

She rolls her eyes and groans. ‘Say it backwards, you tit. God, you are so thick.’

Sudden delight. A new game. They play it all summer, infuriating their parents with the simple code.

‘Cuff the ecilop,’ he says to his dad, trying to pencil in his choice for the 3.15 at Kempton Park.

‘What’s that, a new band?’

‘Sick my bon,’ he says to his mum, as she puts away the shopping.

‘That’s nice, dear.’

He and Ally, crying with laughter, close to suffocation sometimes with the pointless hilarity of it all. Had they laughed so much in the years since? Had they laughed at all? They had ruled Finsbury Park back then; he had never had anything but good memories of the place, an age before Stanniford’s stain crept all over his thoughts.

Somehow he did sleep, his edges softened by memories of childhood. When he wakened, an hour before the sun was due to rise, he was shivering, having shrugged off his leather jacket. He got up, washed quickly in the kitchen sink, and stole an apple for his breakfast from Paul’s fridge. He was at the front door, about to let himself out, when he paused. He could hear his erstwhile brother-in-law’s laboured breathing from the bedroom. Part of him wanted to sneak a glimpse of it to see how much of Ally remained in there. Quite a bit, he suspected, given Paul’s apparent inability to sweep away the cobwebs and start afresh.

He unzipped his jeans and pissed into Paul’s coat pocket. Then he went out, and slammed the door behind him as hard as he could.

*

Haslam was asleep. Tasker watched the other man slowly drool across the dashboard of his car. His face was too fucking big for his features; Tasker hated that. He also hated the fact that Haslam wore one of those stupid pins that went through the collars of his shirt with a fine chain attached that rested on the front of his knotted tie. He hadn’t seen those since he was at school. He hated Haslam’s thick bottom lip and thin upper one. He constantly looked like a camel chewing a bit of toffee. The twat.

‘Twat,’ he said.

‘Hey?’ Haslam came out of sleep and regarded Tasker with red-rimmed eyes.

‘Wake up, Sparky,’ Tasker said. ‘No bonus for you if you sleep on the job.’

‘I wasn’t sleeping. I was resting my eyes.’

‘Rest your fucking lip,’ Tasker said. He could feel himself getting fired up inside, the way he felt whenever he day-dreamed about violence. He wanted Haslam to slap him, so he could retaliate with an excuse, really go to work on him without worrying about how Stanniford would react.

He craned his neck and looked up at Stanniford’s office. He suspected the light there had burned all night, certainly for as long as they’d been there, which was about two and a half hours now, since Stanniford called them in on the mobile. ‘You guard that fucking entrance during the night from now on,’ he’d said, in a strangled voice. Soft old fucker. Shitting himself in his little room. Sucking on the voddie bottle like it was a nipple.

‘Nothing will get past,’ Tasker had said. His jaw still twinged occasionally where Kelleher had tapped him with the bat. Sometimes he lay awake in bed, trembling with the need to pay him back, with interest.

‘I want some coffee. Is the rag-head’s shop open yet? You want some coffee?’

‘Stay in the fucking car.’

Seven Sisters Road was gearing tself up for the morning’s rush. Buses carrying the first wave of commuters — the zombified 6 am shifts — rattled by, breathing diesel fumes all over Tasker’s Beemer, parked illegally on the pavement by the bowling alley on Stroud Green Road. Tasker caught sight of Stanniford at the window, a man whose face seemed to be made entirely of shadow, his body beneath the immaculate suit of stuff barely more tangible. He saw Stanniford rub his mouth and loosen his tie. Then the light went off.

Difficult for a man to do, even Stanniford, when you were twenty feet away from the light switch.

‘Shit,’ Tasker said. He got out of the car and that was what saved his life. He was into the road, Haslam mimicking him with a falsetto voice: Stay in the fucking car, stay in the fucking car, when it went up like a rigged vehicle in a James Bond film. The blast helped Tasker to cross the street faster than he would otherwise have managed, and he hit the doorway of a hairdressers hard, thinking as he went down how grateful he was that the door was made of wood and not glass.

Haslam tried to follow him, the poor, game fuck. But he was never going to get too far with both his legs gone at the knees and fire fucking him over every square inch of his body.

Tasker was on his feet and moving to the entrance to Stanniford’s gaff before the other man had given up and turned instead to the small matter of his own death.

*

The sky was putting on some blusher, but it was still too dark in the room to see what had gone down. Tasker toed the threshold, looking in, wetting and re-wetting his lips, his eyes as wide as he could get them, sucking in every possible crumb of light, trying to put some meaning to the shapes in front of him.

‘John?’ he said. His voice hit the wall and dropped, much as he had done only a minute or so before. There were no other sounds. ‘Kelleher?’

A voice. Little more than a whisper. What was it saying? Oh, God, something like that.

‘John? John. Are you all right?’

He edged into the room. It looked as if Kelleher had been and gone, but too fast, perhaps, to make sure of a kill. A shape in the window was too dark to be a cloud, now he was certain that it was blood. And Stanniford’s desk looked as though it had a heap of clothing on it. The light was improving all the time. He could discern the soft gleam of Stanniford’s expensive suit, sprawled over the blotter and the phone. He saw a foot twitch. Tasker entered the room and switched on the light, but the bulb had been removed.

Fuck.

‘It’s okay, John,’ he said, edging closer. He thought he could smell the smoke from the burning car coming up the stairs after him. It wouldn’t be long before the filth turned up. He switched the Brocock to his other hand and fished out his Nokia.

He was dialling for an ambulance when Stanniford shifted on the desk, rolled over slightly. Something wasn’t quite right.

‘Oh, Dod…Oh, Dod.’

There was too much bulk for the man to be Stanniford. Then maybe Stanniford had got his shot in first and put his man down. In which case, where was his boss?

‘Oh, Dod.’

‘What the fuck — ’ Tasker said. His last words as Stanniford moved, fast, much too fast for a man turned stale after years of sitting behind a desk drinking neat vodka.

Kelleher, in a jacket much too tight for him, grinned up at Tasker and showed him the muzzle of his Glock. ‘Oh, Dod,’ he said again. ‘And you’re as dead as.’

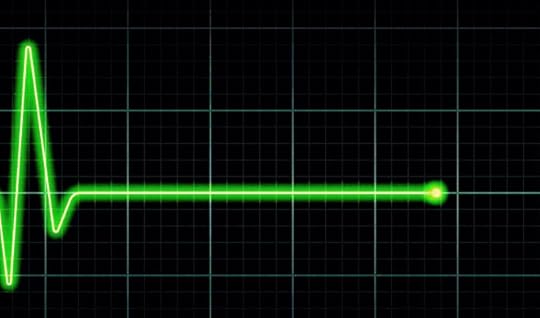

One shot.

*

He took off Stanniford’s jacket and ruined it by covering Tasker’s body. Then he went over to the bar and pulled Stanniford out from behind it by the hair and the plastic ties that bound his wrists and feet. The older man’s face was red with effort. Perhaps he was choking on the gag. Maybe he was having a heart attack. Get in quick then.

Sirens were approaching, still half a mile away, perhaps. With any luck they’d be preoccupied by the burning car in Fonthill Road.

‘Bye, John,’ he said. ‘I hope you’ve got Fran’s sweet face in your thoughts right now.’

Kelleher never wanted Stanniford’s face in his thoughts again so he shot him in it six times. He reloaded the Glock, and shot him again until the trigger was clicking on the spent clip. Another six ought to do it, he thought. He needed a lot of blood, more perhaps than Stanniford was carrying, for the message, the fucking letter, he wanted to write on his walls.

December 3, 2015

Advent Stories #3

FAILURE

Patrick stepped from the bus into a Cologne morning filled with pigeons and rain. The Rhein moped away to his left, flat and grey, listless as he himself had felt this past month or so. Sigi had grown impatient with his lethargy and bombarded him with insults when she returned from the museum to find him staring out at the lowering sky or lounging in the bath, his skin pruning like that of an old man. ‘I can’t carry the both of us,’ she’d say, fretting waspishly at a cigarette. ‘You must find work. Your studies don’t eat up that much time that you couldn’t wait on tables a few hours each week. You must find work.’

Come midnight, when they were shivering beneath blankets in her bed, she would parry his advances and sometimes weep into her pillow. Patrick’s argument that his research would suffer should he have to find employment no longer made an impact on Sigi. ‘What if we were to split up? What then? You would have no choice.’

She was right, of course. Patrick had proved something of a parasite these past few months as what had begun as a very casual relationship turned into something more intimate without any discussion or analysis forthcoming from either party. An irony existed in that he had had a job before he met Sigi; basic administrative duties in an accountancy firm just off Konrad Adenauer Ufer. Dull, but it paid for the essentials. And then Sigi, followed by infatuation, love and a complete loss of responsibility. Instead of turning up to work he would spend hours grazing the dips and swells of her body. They would sneak off to walk the banks of the river for hours on end, feed each other apfel strudel driving a borrowed car on the autobahn with the windows down and Nirvana’s About a Girl slinking from the speakers. And then Sigi finished college and landed a job at the Arts and Crafts Museum just as Herr Schellenberg reached the end of his tether and told Patrick his absenteeism was unacceptable and it would be for the best if he found a job elsewhere.

But it was so much easier to vegetate in Sigi’s flat.

Until now of course. ‘There are no opportunities, Sigi,’ he appealed, a few nights ago. ‘For every job there are three people available.’ And her riposte: ‘You make your opportunities!’ It was a tiff that had escalated at frightening speed, culminating in Sigi’s threat to either kill him or herself. Though he guessed the warning to be hollow, the sheer fury and frustration in her voice had finally shocked him into accepting that measures needed to be taken. He had called Josef as soon as he had a moment alone.

Last night they had made love for the first time in weeks. It had been a cold, textbook affair. Head resting on his chest she’d said: ‘Patrick, I’m at my wits’ end. There is talk at the museum of laying off some of the staff. The recession is picking people off one by one. If I lose my job, we lose this.’ Her gesture took in what their life meant to them at the moment, all of it within arm’s reach: a few books, a suitcase of clothes, a photograph album. The flat itself. He made her breakfast and kissed her goodbye, watching the way she moved down the steps to the street, pony tail bobbing.

He followed Josef’s directions, angling down a cobbled road beneath an archway off Pfälzerstrasse where blouses and towels hung out to dry whipped about like strange birds trapped in netting. He seated himself outside the café beneath a birch tree filled with copper chimes and let their music relax him, knowing that Josef would doubtless be ten or fifteen minutes late for their meeting.

Patrick had met Sigi at a party thrown by an ex-girlfriend who lived in Koblenz. Patrick guessed he’d been invited just so Heidi could rub his nose in the success she was enjoying these days: she was like that. He went along just for the sour victory of proving this prediction and he was not disappointed; Heidi was swift to show him her new boyfriend (a tanned, flat-stomached astro-physics graduate called Wolf); her new flat; her car; on and on and on. He bumped into Sigi in front of the open fire where surreptitiously they tossed Heidi’s business card to the flames at the same time and howled over the coincidence of such an act.

‘Oh but wait,’ she’d said, stifling her laughter, ‘it wouldn’t surprise me if this fire was being fuelled with Heidi’s precious business cards. Isn’t she just insufferable?’

She didn’t apologise when Patrick told her she was a former girlfriend, a matter that impressed him. Within the hour they’d traded telephone numbers and lingered over a goodbye that had left Patrick dry-mouthed and palpitating, remarkable for the fact that their proximity had only encompassed a handshake and eye contact. It pained him to think of her, six months on, her eyes less vibrant, her posture collapsing in on itself. He wondered if she had any ambition left; certainly the fiery creature he’d once seen her to be had grown sullen and maudlin. It wasn’t all his fault, surely?

‘We’ll take a drink, I suggest. To celebrate our meeting again. It’s been a while, no?’ Josef towered above him – he was almost a foot taller – and clapped a huge hand on his shoulder.

Inside the café they ordered bottles of Pils and spent a while splitting open pistachio nuts, watching the video screens.

‘Thank you for coming Josef. I know how busy you are.’

‘Remember summer? Three years ago? The last time we spoke.’ Josef chewed slowly, fingernails worrying at the hasp of his Filofax. His suit rippled and shone so readily it might have been made from water.

‘Of course I do. You know I do.’

‘It was not an enjoyable time. For you, that is. Especially for you.’

Patrick shook his head. ‘I know. But I’d be interested in something like that again. It would be worth the fear.’

‘Things are that bad?’

‘Worse. I think Sigi will leave me if I don’t find some money soon. I’ve been such a shit to her.’

Patrick felt the weight of Josef’s gaze, and the thickness of the silence that spread between them. Then Josef leant close enough for Patrick to smell the sweetness of his breath, his lavish perfume.

‘I have excellent contacts these days. In this city there works a man who can make you rich, if you have the stomach for what he would do with you.’

‘This is how you make your money?’

‘Christ no! I’m not desperate. I… supply him with his raw materials. He pays me well, but then, so do many of my business associates.’

‘I don’t like that. Raw materials? This is how you see me?’ Patrick took a long swig of his beer. Around them, the bar drew in towards them, as though air were being sucked out of the building, pulling everyone closer together. Patrick could smell aftershaves clashing; a hot volley of cooked sausages; even the tacky, sugary teats depending from the liquor optics. A barmaid wearing luridly coloured hair extensions pulled the hem of her tee-shirt down till the cotton creaked. Patrick watched a single gem of sweat stroke a line from the back of her ear to a gold choker where it sizzled brightly.

Josef, for the first time, was betraying his impatience with a long suck on his teeth and a crinkling in the soft folds at the corner of his eyes. ‘Why are you here? In Köln? Do you remember your reasons for coming here?’

‘Of course I do,’ said Patrick flatly. ‘To broaden the scope of my research.’ The words aired as dispassionately as those of a child regurgitating rote-learned multiplication.

‘This is untrue. You came here to make money. You came here for the butchers, you said. Medical experiments were limited in Britain; their wages weren’t enough to pay for the drugs you needed in order to put your belly right after filling them with chemicals week after week. You said.’ Josef stressed the last words with a poke of his finger into the limp shield of Patrick’s shoulder blade.

‘So what if my feelings are different now?’ Patrick argued, all the while thinking: He’s right, the bastard’s right. There’d been that time when the 8th and 15th of each month meant a trek to and from Leeds so that he could swallow half a pint of an untested lemon and lime flavoured drink called FYBOGEL which was being hailed for its potential cholesterol reducing properties. Was it worth £1000, travel included? Hardly. There’d been the 3Cs too; Common Cold Centres he haunted during the late 80s till research funds became so piddling that they closed down. It had felt like he was being made redundant – only without the severance pay. He’d talked to a few friends about the dismal situation, one of which had suggested getting in touch with Josef. Josef with his Technicolor labcoat promises of injections and induced muscle spasm and sleep trials and mild Electro Convulsive Therapy. All designed to line his ruptured pockets with marks and pfennigs. He’d come across the water, helpless as a Bisto kid, floating on the anaesthesia which poured from Josef’s lips. In the foetus crease of sleep he’d danced with molecules that whispered their drowsy names into the very gristle between his ears: thiopentane, helothane, enflurane. He spent soporific breakfasts popping ‘jellies’, his body gradually becoming conversant with the torpid heat of temazepam and omnopon. In the University library where he was to land his doomed job, amputated chunks of sunlight scattering the dust and people, scalpels grinned at him from the pages of the British Journal of Surgery.

‘Who is it you know? What can he offer me?’

Josef’s presence seemed to diminish, a salesman who has hooked into a big fish and can finally relax. As he softened, he slid into the chair next to Patrick and blinked for what must have been the first time. Now he was at eye level with Patrick, his clout retreating, Patrick could only wonder at the chameleon nature of his character, the way he had piled on so much unspoken pressure, his bullyboy charm.

‘You can make £12,000.’

Patrick scoffed and turned to look into his friend’s concave face, at the wide spaced eyes that seem almost to be turned in towards each other. A smile played in there, like a candle in a bowl, tinting the edges of his face with light. Fuck, Patrick thought, he really means it.

‘Yeah,’ he humoured, ‘and what would I have to do for twelve grand?’

Josef’s smile faded. He wore the countenance of one searching a set of features for steel, for inner grit.

‘Die a little,’ he said.

*

Sigi was asleep under the yucca, headphones on. The only light in the room came from the dancing equaliser on their stereo and the violet neon from the snooker hall across the street. He left it that way.

She came to bed hours later and he watched her undress from the half mask of their blanket. Sigi rubbed her neck where the cold had stiffened it and applied a little night cream to her cheekbones and forehead. She brushed her hair. She lalled a fragment from whatever song was looping in her mind; something that sounded like I got so high, I scratched till I bled before killing the light and smothering his chest with her heartbeat. Her mouth and cunt made gummy demands on his skin but it was too much like being dabbed with open wounds. He pushed her away and felt her dampness on his thigh tighten and dry. When her hand scooted under his leg to gently mash his balls, peel the skin back from a reluctant hard-on, he tried to relax. Her thumb capped his tip, smeared a tear of fluid over his glans and: ‘Fuck me, Pat. Come on.’

The flesh across his chest tightened so swiftly he almost heard his skin tearing. In there, bloated within its cell of ribs, he convulsed and spat; a leathery knot tiring all the while. His fear travelled quick as his blood; he dwindled in her fingers.

‘What’s wrong?’ her voice was thick with sex. She sat up. He saw the spike of a nipple against the window; a curtain of hair sweep the wedge of her brow; cilia eyelashes flutter in uncertainty. He imagined the purple net of veins stutter on his retina. Ear-drums concussing with the pressure of his blood as if it wanted to be away from the body which contained it.

Again, her question, voice see-sawing on a fulcrum of confusion, not yet knowing whether to lend weight to the cynical end or its charitable opposite.

‘I’m tired.’

‘What have you got to be tired for?’ The sudden injection of outrage, for the first time, was unable to find its way through to him. He lay there, numbed as she ranted, to her credit finding new ways to express old, old things. But it didn’t matter how much she dressed the words up; they could make no impact on him any more. He wondered if that was because their content was stale or the person delivering them was no longer so vital to him. And, consequently, was that feeling merely forced by his reluctance to tell Sigi where he had been, what might be in store for him? Was he trying to hate her in order to spare her?

He listened to the music of her body when finally she slept. All of it seemed circular, reproductive: the wet mechanics of her breathing; the dull knell of her heart; occasional glottal murmurs. It all sounded too insular and stale. He knew that trawling his memories for something soothing was likely only to fret him more but he couldn’t prevent a regression; insomnia seemed to be its perfect bedfellow.

*

Meat. Sunday afternoons hanging round the kitchen with the cats waiting for Mum to finish roasting the hunk of dead stuff in the oven. Patrick liked lamb best; the fat blistering and loose on the rich, dark meat. He was never able to finish his serving, mainly because Mum always dished out too many slabs of the stuff but also because he didn’t want Gatsby and Mac to go without a few scraps from his plate. And one time, everyone was rushing around for some reason or other: Dad had a meeting to attend; his sister Mo was helping a friend with her display at an art gallery. And Mum was gearing up to go to a yoga session – she wasn’t eating till later. Only Patrick was free of obligations: he tooled around with Gatsby, a ping-pong ball and Dad’s shoe while Mum clattered her timpani orchestra on the old Belling cooker.

Tucking in while Mum stuffed a duffel bag with leggings and leotard. The first cut of Patrick’s knife brought a dribble of blood from the spongy pink cross section of meat; it spread in a watery pool to infect his mashed potato. Dad and Mo were mopping up spillages, scraping and slurping: pulpy noises at the centre of his world. He imagined blood forming a thin wash on their gums, swilling hotly in bellies packed like haggis. Then a whitening as the kitchen faded and his chair didn’t feel as though it could support him properly.

Dad leaning over him: vermilion lips peeled back. Clotted, meaty breath.

Patrick had steered clear of red meat ever since.

Hours later he slid from the sheets feeling misshapen, as though, during the night, he’d been eclipsed and gently crushed by a giant fist. He scrimped breakfast from a curl of bread in the larder, a rind of tired cheese. Coffee was in abundance but he could hardly brew up without rousing Sigi. He didn’t want her questioning him; he didn’t want to let on as to the nature of his insomnia.

Josef’s BMW was a lozenge of black assuming form out of the soupy half–light beneath the railway bridge. Inside (against the fetor of leather upholstery), was a fleeting whiff of freesias, money – a stale waft of fanned banknotes – and Doublemint. Patrick listened to the whispering engine, the chuckle of an unseen fountain. Water always made Patrick feel cold. His upper arms he pushed against the shivering shanks of his chest, hoping Josef wouldn’t notice and misinterpret the gesture as fear but his friend was busy clipping a large cigar.

‘Well?’ Patrick quailed at the pleading in his voice. He so wanted to prove his mettle, not only to Josef – and Sigi – but to himself. Since his voice broke he’d been cursed with a reedy delivery, lacking any character building inflection, any gravel or, conversely, any silkiness, like the brogues he’d known when relatives visited from Ireland years ago. People such as Josef, though no bigger in stature, could pinch out Patrick’s light with an articulation only dreamt of by the other.

Josef wouldn’t allow himself to be hurried. He bolted the cigar between his teeth and torched it with a match which seemed to have extended from hisfingers. ‘You – paff – told – piff – her – poff poff?’

‘Of course I did.’

‘The boy lies. He lies well, but not well enough.’ For the first time Josef eyeballed him. The buffer of smoke made his face appear unstable; his mouth roiled around the cigar and Patrick found it easier to follow the orange pastille of its coal than the eyes behind it.

‘Christ Josef, if I told her, do you think I’d be here? I’d be out on my arse. Better I just do it and come back with the cash. Then I’ll tell her.’

‘Because then, if she kicked you out, you’d have your own money to take care of you, instead of hers.’ He grinned: the cigar grew erect, gleaming on the narrow bridge of Josef’s brow.

‘Look, it was you. You who encouraged me to go for this. Why do you want to piss me off about it?’

‘Because I can. So easy.’ He shifted the gear out of Park and into Drive; let the car mosey over the cobbled alley till, hitting the main street, he dipped his foot and Patrick was pressed back into the bucket seat. If he looked out of the passenger window on his right, the houses and hedges – all that was solid and detailed – grew molten.

*

Sloe-eyed Sigi passing him a dry Martini. ‘See?’ she said. ‘See how you have to make sure the glass is cold? Now rinse it with vermouth and throw the excess away; you just need to coat the glass. Pour your gin from an ice cold shaker. Olive.’

The way she pronounced olive – as Oh-live – made him laugh. Her lips were wet with traces of cocktail; teeth too as she smiled, as though the reaches of her mouth were flush with a layer of cellophane. This image clogged in his mind as they took a series of lefts and rights through an area of the town he was unfamiliar with (gabled roofs and streetlamps like unfinished gallows; block buildings with pastel slivers in frameless windows). A woman in white with a gash of red silk at her throat rode by on a piebald horse. Trees encroached, first dotted between, then concealing and finally replacing the houses on the city’s limits. Patrick suddenly realised he was wearing the necklace Sigi had bought him during the summer – the last gift she had proffered before their current impasse. It was a simple claw of metal gripping a blueish enamel swirl which he wore on a leather cord. He liked its weight against his sternum; during lovemaking, it would answer the knock of his heart against his ribs with a dull call of its own. Sometimes, as she peaked, Sigi would draw it into her mouth and suck on it till her bucking waned.

‘This is how it shall be.’ Josef spat the butt of his cigar out of the window and didn’t speak again till the electrics had sealed it once more. ‘We go in. I talk to Brandywine and Losh. You do your stuff. We get paid. We go out.’

‘We? We get paid?’

‘Yeah, we. I’m acting as your agent on this, remember.’

‘So what’s your cut?’

‘Not as painful as your cut, I can assure you.’

‘Bastard.’ Patrick felt like ordering him to stop so he could get out and walk home. ‘Maybe I should become an agent.’

‘You don’t have the contacts or the cuntishness. And you speak German with all the composure of a tightrope walker with one leg suffering from Parkinson’s who is in the midst of morphine withdrawal.’

‘What’s your cut?’ Patrick didn’t really want to know any more, but he’d just caught sight of a building through the net of branches up ahead and felt the first slow convulsion of fear in his loins. Hearing his voice – andJosef’s smug rejoinders – was helping to nail his panic down.

‘Six k.’ And then, as if parrying any protest of Patrick’s before it was aired: ‘Do you know how hard it is, liaising? How perilous? There are butchers in this country, Patrick. I’ve worked laboriously to get you this and you can be sure you’ll be treated well. Proper anaesthetists, sterile conditions that are second to none, excellent post-op and Intensive Care facilities.’ He risked a cheeky glance, perhaps gauging the humour of his friend before mugging: ‘If you snuffed it here, the quality of your death would be orgasmic.’

Patrick sneered; his hands were greasing up. He couldn’t summon the spit he needed to coat his words with venom. ‘Not funny,’ he wheezed, but Josef was corpsing, ratcheting the car into a space it seemed was designed for a motor half the size.

‘Let’s be having you, my lad,’ he soothed, releasing the child lock so that Patrick could get out.

The air. The air was brittle and rarefied, as though cleansed in a filter made of pure ice. When his foot crunched satisfyingly into the gravel of the car park, he thought his metatarsals had powdered from fear-weakness.

‘I can’t do this,’ he whispered as Josef steered him into the revolving door.

‘But you will, all the same.’

They were met by a woman in a starchy, cream suit. She wore her hair in a Thatchered black hive; a silver brooch in the shape of a heart clung to her left nipple area.

‘Imogen,’ she said, a rising note on the last syllable so it seemed she were addressing Patrick thus. He was about to deny the name before realising what she meant, not that he could have summoned the clout required to send adequate breath past his vocal cords.

An odd gesture busied her hand: it dived down, index finger pointing to the floor, thumb stuck out at 45°. The rest of her digits tried to press themselves against her wrist. Patrick saw, very clearly, a tendon and a vein rise against the skin, like flaccid rubber hosing suddenly made stiff with water. Her other hand fussed at the back of his, making his knuckles hot. ‘If you’ll just wait here,’ she said, ‘I’ll get Dr Losh to come and see to you.’

There were no paintings or flowers; nothing resting on the desk marked Reception bar an open ledger, pages blank. There wasn’t even a receptionist. Or any of the bustle Patrick might have associated with a hospital.

‘Who said this was a hospital?’ countered Josef when Patrick explained his unease.

‘What is it then?’

Josef didn’t answer. Instead, he led the way forward, down a corridor that was at least as bland and thinly antiseptic as he would expect. At the far end, a trolley came into view, pushed by a tall black man who wore a mask and glasses which filled with white light when he turned his head to look towards them. Patrick saw something small and dark fall from under the crumpled blankets. They didn’t appear to be getting any closer to him, despite Josef’s devouring stride. The trolley, and its guardian, disappeared into the white perfection of the opposite wall; Patrick could hear a dodgy caster protesting in diminuendo.

‘Know the tools of your torture,’ said Josef, but his mouth was shut. Somehow, without his knowing, Patrick’s hand had been subsumed by his friend’s. At last, they reached the end of the corridor and Patrick could see the splash of red that had fallen from beneath the blanket. This, at the same time as a man dipped through a doorway, hand extended, beard shifting to display a greenish scythe of teeth. Patrick leaned over, not to accept his salutation, but to catch the gloops of flesh which were sagging from his cheeks before they hit the floor. He couldn’t stop the left side of his face from melting.

Patrick splayed both hands – a kind of Whoa, let’s just calm everything down and be rational gesture. ‘This is an unorthodox procedure,’ he meant to say, but his lips kept stumbling on the fourth word. His knuckles itched where she had been fussing at them.

‘I’m Reuben Losh,’ the beard said, slipping a business card into Patrick’s shirt pocket. ‘What’s that? Unearth a what? An ox?’ Josef and the doctor laughed; Patrick watched their faces mingle, mouths folding together like something monstrous and Picasso-like, tilting on different planes.

He found that he could move much more freely now that Josef had let go of his hand, but it was probably because he was lying on a trolley, fading fast, losing all sense of what was ceiling and what was floor.

Brilliant light. So bright it was almost liquid; so liquid he could see the splinters of colour refracting, some of which he could give no name to because of their immediacy and freshness.

‘Patrick…’ Losh swam into view, his head causing an eclipse of the operating spotlights. His beard was like the copper wire graveyard of an electrician’s dustbin. ‘I want you to meet Dr Olivia Brandywine. She’ll be monitoring you while I still your beating heart, ha ha.’

Patrick didn’t see Brandywine, only felt a hand cup his shoulder, and catch a peripheral glimpse of flesh that seemed bleached and smooth to the point of plasticity. ‘We’ll need to send you deeper, Patrick,’ she soothed, with a smoke-scarred voice that was not unpleasant. ‘I’ll be administering a general anaesthetic and then Dr Losh will puncture your femoral artery. We need to feed a catheter along the vessel to the sinoatrial node in your heart. Once we’ve found that, we’ll send some radio waves to cause an arrest. I want to record your body’s reaction –

Another sting in the dip of his arm. Shouldn’t I be given a medical first? He felt heat sweeping up towards his neck.

– and then we’ll have you up and out of here before you know it.’

*

00.01

black upon me like that zoo time when a murder of crows falls out of the trees a strange sudden autumn full of screaming and mummy scratched from lip to ear and my heart full in my throat dreadfully sorry dreadfully sorry madam shall i call an ambulance here sonny have an ice cream courtesy of the management

00.02

maggie’s lips cold and blueish when she kisses me christmas day messing with mistletoe what will you do if i pin some to my fly maggie hey maggie and laughing and the smell of her breath oaten and chocolatey and wild and a lipstick heart on my wrist we run through forest brambles and the welts are still healing on my legs when she tells me it’s all over

00.03

sigi (oh sigi i love you) tossing me off for the first time in the back of her beetle as night spreads itself across the industrial estate and i come into the wad of tissues she’s stashed up her cardigan sleeve and she’s amazed at my quantity and she kisses the tip even as it twitches and weeps like something rent open and left for dead

00.04

I’m feeling cold. And halted, funnily enough. A feeling of stasis – could be my pumpless blood, settling thanks to a gravity it’s never known before. I’m able to think though there’s a godawful storm at the edge of my awareness, like a piece of paper lit at the edges, eating its way towards the centre, but no pain, only a tickling sensation deep inside. No ships sailing towards me for that rubicon moment. No dark tunnels or horizons of white light. No out of body

00.05

experiences like the time i burned my hand on the electric ring on mum’s old stove watching the clean red spiral blacken must be cool now but such a depth of pain that i can’t even bring it to mind but mum being mum always mum pressing her mouth against the hurt and blowing gently as i cry my heart out

00.06

in the bowl of my home town the rarity of snow whitens the grimy avenues and dad readies to take my sister mo and i on a walk to the land of far beyond where’s that i ask him far beyond he replies pulling on my wellies and we go out i’m humming a song from the beatles film on tv let it be and the warmth in my fingers and toes retreats and we all make breath sculptures in the chill down by the canal where they’re landscaping and knocking down old pill boxes and strange roads filled with glass cobbles the fallen tree is ash coloured with mould and snow and dad’s daft sayings the camels are coming hurrah hurrah and even my sister’s tiny tears looks frozen to death in the dusted patch of rhododendrons i spy a red swatch of cloth brighter than blood we’ve arrived dad says

00.07

morgan and me eating blood oranges on the train to Manchester we’ve got seven quid between us all of it going on the new police album and at birchwood station she gets on board and sits opposite her eyes like smoke made solid smiling at us at the sticky glaze on mouths agog and before we reach piccadilly morgan’s getting all cheeky with her saying give us a sticky snog love and shoving his fist up his top thrashing it around to mime a heart out of control when she blows us a kiss

00.08

There’s a definite kind of brittle coldness suffusing my limbs now but it’s not unpleasant. Not like I can feel Death’s fingers giving me a massage. The voices are calming and sufficiently distant to negate my understanding their content. I have the image of Dr Brandywine in my head with her tapered fingernails deep inside me, coaxing my heart awake. Sigi. It’s a feeling Sigi gives me all the time. I have that achy feeling of missing her, even when she’s near. We’ve been together a long time now, yet still I get excited when I know I’ll be meeting her later in the day. I can’t remember how tender her mouth feels against my own

00.09

room is a cell as i grow and more stuff accrues softening the corners erasing the concrete structure of the four walls and helping me lose my sense of place and belonging which i think is precipitating this huge unfocused dream i have though less a dream and more a wall of irresolute significance which includes what might be a stairwell for want of something banal to defuse its threat something approaches from the dark gulf larger than my mind’s confines will allow more momentous than the most extravagant unfurlings of imagination like viewing a fragment of film at a magnification of x10000 all detail lost but the power of violence and substance and movement inflating in my head it comes back regularly it comes even now

00.10

is it death?

00.11

sigi rubbing the oiled wishbone curve of her cleavage into my face steering her nipples into and out of my mouth cupping her breasts together with her remarkable hands pressing their delicate independent weight upon me till it’s hard to breathe and the thud in my head does it belong to me or to her

00.12

o me o my o god

Coming out of it hurt even more. Through the pain, he thought of birth and was almost able to conjure the moment his lungs were shocked into use for the first time. How many of us are born again? he thought, as the trauma of re-animation retreated, having left its fire smouldering in every shred and dribble of his body. His eyes felt poached and tender; the light seemed too much like living matter, crowding his immediate space with swimming motes – he didn’t know whether the headache was a side effect or a result of the insufferable thereness of day.

Only when the colour began to leech back into his vision did he realise he had been without it. Shapes acquired depth and mass. The chair. The table. Josef. He was looking down on Patrick with an expression of dismayed fascination.

‘What is it?’ Patrick asked, through a mouth that felt numb and tight. ‘Have I been amputated by mistake?’

‘No, you look fine. Just a little pale, that’s all.’ Josef recovered his joviality, plonking himself at the foot of the bed. He fished a cheque out of his waistcoat pocket. ‘This’ll keep you in bratwurst for a week or three,’ he said, planting the piece of paper on Patrick’s bare chest. ‘The doctors wanted me to tell you all went swimmingly. They say you can come back in six months for another stint. If you’re up to it.’

‘I don’t think so.’

‘Ah, come on. You’re strong as a piece of my great aunt’s knicker elastic.’

Patrick kicked Josef off the bed. ‘You do it, if you’re so keen. Please leave me alone now.’

Josef made a performance of pulling on his driving gloves. ‘Can’t offer you a lift back into town I’m afraid. Meeting a client in Dortmund this afternoon.’

‘I can go home?’

‘Of course. God, anybody would think you’d undergone major heart surgery.’

After Josef had gone, Patrick lay still for a while, listening for the knock in his chest. It was there, but it sounded hollow and sluggish. He dressed slowly and wandered the corridors till he found the reception where they’d entered, God, just two hours ago. There was nobody to see him off.

Outside, the light was waxy and uncertain, smeared about wads of cumulus like some brilliant resin. He handed over most of his change on the bus back into town, and spent the journey trying not to examine the stagnation within him. It was as if his soul had been taken out and washed of all its interesting impurities and flecks of self. He didn’t feel alive, he just felt as though he was living.

He got off in Herzogstrasse and watched the sky spin around the twin towers of the cathedral while he grew accustomed to the flail of traffic and pedestrians. Walking back to the Kunstgewerbemuseum, he checked the faces of those streaming around him. All were pinkish and vital; varnished eyes and teeth like tablets of ice. He felt stunted and tired in comparison; catching his reflection in a darkened window he was appalled to see how jaundiced he looked. The dough of his face appeared to lack elasticity. Turned off and switched on he’d been – like a car or a transistor radio. Drinking coffee in a backstreet bar, Patrick’s hunch that he’d been soiled, or abused, took on an ever increasing concretion. Should he have been counselled before leaving? He fed coins into the telephone on the counter and dialled the number of the institute on the back of Dr Losh’s card. Nobody answered.

*

In the museum he watched Sigi arranging a pastel display through the gallery’s glass doors. The sunlight had sliced her in half. Even from here, fifty feet away, he could see it playing on the wet curve of her mouth, the loose filaments of hair. In he went. Her smell was upon him; the same sweet odour that rose from the bed when he turned back the blanket in the morning.

‘Sigi?’

She twitched her head his way but said nothing, continuing with her task, perhaps a little more starchily now.

‘Sigi, I’ve made a little money today. A lot, really. I want you to have some.’ He reached for her but she ducked away before striding backwards, hands planted in her back pockets.

‘Is that picture straight?’ she asked, so softly it might have been to herself. She hadn’t looked at him yet.

‘Sigi.’

Now she fastened him with the angry green of her eyes. If she saw anything lacking in his countenance she didn’t let on. ‘We’re through, Patrick. Can’t you see that, honey?’

‘But I’ve made some money.’

‘Congratulations. Go and spend it. And then wonder where the next lot is going to come from.’

‘If it hadn’t been for you, I’d still be earning at the accountancy firm,’ he regretted the jibe, and the way he’d said it as soon as his mouth was shut.

‘Get a life, you sad bastard.’

‘But I love you,’ he finished lamely.

‘I’m tired,’ she said. She seemed almost not to notice him, to be looking through him, as though he were made of glass or water. ‘I don’t want you to be there when I get back tonight. I’m sorry.’ She tried a smile; her lips merely thinned. ‘I’m sorry.’

*

Patrick scuffed about the flat for a while, desultorily bagging his things (a piffling amount) and delving into his past for happy moments to feed the sense of loss that must come to him soon. He considered a number of follies: he’d open a vein in her bath tub, burn the cheque in front of her, leave the cheque on her pillow. In the end, he did nothing, simply sat in her rocking chair by the window and watched the boats fart and froth in the Rhein till darkness crept upon the city, flooding it with streetlamps. His body still felt strangely bland and ropy; the squish of meat in his chest was making him ill. He lit a candle and tossed his keys on to her desk. As he went to the door, a book caught his eye. It was lying flat on her shelf whereas the others were erect, a volume he’d given to Sigi early on when gifts and cards were exchanged as gladly as kisses and hugs. A novel she enjoyed, as he recalled. Picking it up, he leafed through, bending to smell the paper’s age. His riffling was halted by the card, a simple white affair with a pale heart sketched into a corner. Inside, his hesitant hand, in dark ink:

Always.

December 1, 2015

Advent Stories #2

TO THE BEACH

Petra was all for it, which scared me deeply. I knew I would have to go along with her or risk losing her to Prentiss or Fauchon, the only other fertile members of our Warren. I wasn’t ready for that, not when I’d spent the best part of a year applying for a conjoinment. The other boys were younger, healthier than me; I could sometimes hear them beyond my wall, spending their lust on each other or on the matriarchs who were barren and dying.

What I’d initially hoped was idle fancy on Petra’s part had soon formed the focus of her every waking moment. Fatuous as it was trying to dissuade her I found myself attempting just that one night during breakfast. I waited till the screens came down, knowing how the stars and that faint, diminishing smear of red relaxed her (not me; that colour and the body it signifies chilled me to the quick). As I composed my argument I watched her eat, her golden eyes fixed on the thickening dark.

‘It’s suicide,’ I said.

‘Not if we take care,’ she countered, so quickly it seemed she’d been rehearsing her gainsay. ‘Then it would be as close to living as we’ll ever get.’ She stretched, pushing away her tray of powdered fruit and water tablets. The hairless curves of her body looked jaundiced and tired this evening; at least the sores she (and all of us) had inherited were weeping less.

‘There’s more to life than dreams, Petra. They more or less died with the City.’

‘You don’t dream?’ Had she eyebrows they’d have arched.

‘I didn’t say that. But I know the value of keeping a dream in its place.’

‘In its grave more like.’ The bitterness in her voice unsettled me. Would Prentiss have the balls for this? Fauchon probably did it all the time. They’d be her next port of call if I wimped out.

‘The sentries, Petra,’ I pleaded. ‘The cameras. The Craw.’

She swept her plates to one side and spread herself over me, sensing victory. ‘The Craw has never been seen baby love. I never knew you were a sucker for myths.’

‘What do we do when the sun comes up?’ I asked, thinking, shit I’m going to do this.

‘We find a place to hide,’ spoken as if I was an idiot.