Conrad Williams's Blog, page 18

July 15, 2013

The Dated Novel

Photo from http://www.silentuk.com

In 2003 I wrote a novel called Blonde on a Stick. The climax to that book occurs on the roof of the train shed at St Pancras, accessed via the desiccated rooms and corridors of the rotting Midland Grand Hotel. A chase scene beforehand had taken in the construction work occurring around what is now the gleaming Eurostar hub.

You could take a tour of the hotel back then, and this I did, soaking up the atmosphere of a magnificent building gone to seed; a sleeping giant. Every room was a riot of peeling paint and mildew, with dusty corpses of spiders and flies wadded in the corners. It was a building teeming with ghosts, a glorious setting for a story. My novel was not published until 2011, and in the intervening years the old Midland was refurbished on a spectacular scale and is now the St Pancras Renaissance. I worried for a long time over that facelift, and whether I should shift the end of my novel to a new locale in order to rescue the book from being dated, but surely such a fate is inevitable for all novels rooted in real towns and cities. Possibly this architectural dating isn’t as deleterious to a book’s fortunes than, say, the jargon of a specific period, Daddio, or references to how much certain things cost (you could buy a pint for thre’pence ha’penny and still have change left over for a powdered egg supper and a lift home on t’Hansom cab). My fear of including anything that might date the piece of fiction I’m working on is less to do with anchoring my characters in a specific era, and more to do with jolting the reader from the story. An early short of mine (my first published piece, actually) – Dirty Water – sold in 1987 to a small press publication called Dark Dreams, contains a reference to the British Gas privatisation adverts. Anybody remember Sid?

What do you think? Are there any books out there that failed to age well?

July 9, 2013

My Top Ten non-horror films #1

1 – CHINATOWN (1974)

An utterly sumptuous film, beautiful to look at, brilliantly scripted, directed and acted, and containing everything you would want from a story: drama, thrills, intrigue, humour, tragedy and a deep, painful twist. Robert Towne’s screenplay is an object lesson in writing for the movies, but fair play to Roman Polanski for pressing for that dark, dark climax. I love Jerry Goldsmith’s shimmering score, the chemistry between Nicholson and Dunaway (her awkwardness, his almost disgusted curiosity in her), John Huston’s towering menace, and the fact that the story could have been done and dusted during Jake Gittes’ first visit to the Mulwray household, when he sees something gleaming in the pond (bad for glass) but is disturbed from his retrieval of it by Evelyn… Wonderful cinema.

July 2, 2013

My Top Ten non-horror films # 2

2 – THE GODFATHER (1972 – 1990)

I’m going to be cheeky and include all three films as one entry, mainly because whenever I watch the first, then I always end up watching the next two as well, so for me this is just one big story.

I love the look of the films, dark, grainy, infused with a sepia tint, and laden with menace. There are so many wonderful scenes in these films, many of them so tense it’s almost unbearable: the meeting in the restaurant where Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) leaves behind his life as an American hero at the expense of drug lord Virgil Sollozzo and corrupt police Captain McCluskey. Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro)’s scorpion dance with dandified extortionist Don Fanucci in the sequel. The final scene in The Godfather III when Michael Corleone is stalked at the theatre. Object lessons in pacing.

The films are shot through with marvellous performances from Pacino, James Caan, De Niro, Marlon Brando, John Cazale and Robert Duvall. A woman’s world this is not, but Talia Shire has a few powerful cameos. This is yet another Coppola release that charts the long-term destruction of a human soul. Beautiful and brutal in equal measure. Sublime film-making. Watch out for those oranges…

Interview and story

Mihai Adascalitei interviews me for Revista de Suspans. There is also a story, Slitten Gorge, and another outing for my recent blog post Doorstep Horror. The site is in Romanian, but there are English translations to be found. Check the links to the right of the page.

July 1, 2013

My Top Ten non-horror films #3

3 – THE CONVERSATION (1974)

I loved the rash of paranoid thrillers that came out in the 1970s, particularly The Parallax View, All the President’s Men, Three Days of the Condor and The Conversation. Sandwiched between the first two Godfather films and Apocalypse Now, this was Francis Ford Coppola’s ‘quiet’ project, but it was no less gripping for that. Prescient too, in the way it warned of a society in which every movement, every conversation, every action on a computer can be tracked and traced.

Harry Caul, a professional ‘bugger’, complete with grubby flasher mac, is commissioned by a shadowy client to record a couple as they prowl around a busy park one lunchtime. It’s no easy job. The two are furtive, suspicious, clearly trying to keep their conversation private. Caul’s genius is in being able to cover every angle, no matter where they might decide to go. He’s got supersensitive microphones on roofs, and a bunch of employees on the ground, some so skilled they can record their quarry while walking in front of them. The only problem is that the mics pick up all the ambient noise too, causing much of it to be unintelligible. The way Caul feels his way to their words through the static, using his state-of-the-art tape decks, is an engrossing sight, especially when he uncovers more than he bargained for.

Gene Hackman is brilliant as the socially awkward, intensely private Caul who, like Martin Sheen a couple of years later, endures a shattering descent into his own heart of darkness.

June 28, 2013

My Top Ten non-horror films #4

4 – APOCALYPSE NOW (1979)

Is it ambition or is it excess or is it insanity? Perhaps the last truly epic film, the making of which is as fascinating as the feature itself. It’s film that begs to be seen on a big screen with the sound ramped up. It’s trippy and frightening, and it recreates the hell of the Vietnam war so vividly you might almost believe you were watching some weird kind of documentary. Coppola experienced his own war throughout on a shoot that was meant to take six weeks and ballooned to sixteen months; he was rewriting scenes on the lam, had fired Harvey Keitel and saw his replacement, Martin Sheen, promptly suffer a heart attack. The helicopters they were borrowing from the Philippine government kept being recalled. And to top it off, Marlon Brando arrived on set grossly overweight – not the wiry ex-Green Beret that had been envisaged – having failed to learn his lines.

Nevertheless, it’s rammed with fantastic performances (Robert Duvall’s Kilgore and Dennis Hopper’s frantic photojournalist both stand-out) and memorable set pieces. The growing sense of dread as the gunship Erebus pushes deeper into the heart of darkness is palpable. Brando, wreathed in shadow and spouting random lines of improvised dialogue, is wildly OTT, but you cannot take your eyes off him.

June 24, 2013

My Top Ten non-horror films #5

5 – NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN

Virtually indistinct from the excellent Cormac McCarthy novel, this Coen brothers film introduces you to a monster to equal, if not best, anything seen on the big screen before. Hannibal Lecter? Anton Chigurh makes you look like the pussy cat you are. A wonderful, brave film, with great swathes of silence. It is tense and unconventional and worthy of every award thrown at it. I loved the earlier Coen films such as Fargo, Miller’s Crossing and especially Barton Fink, which would have made this list if NCFOM had not been made, but this film is the first where their weird sense of humour is sidestepped. This one they play for keeps, one of those films that grabs you by the throat and does not let you go, even after the end credits. All the main characters are played to perfection: take a bow Josh Brolin, Kelly MacDonald, Woody Harrelson, Tommy Lee Jones and especially Javier Bardem.

…from my cold, dead hands

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Dylan Thomas

Many of us have jobs. Full-time jobs, part-time jobs, weekend jobs, holiday jobs.

I’ve done my fair share of grim jobs. I’ve delivered pizza. I’ve worked in one of the busiest bars in Warrington on New Year’s Eve. I spent one bewildering day trying to sell kitchens. I sorted out an oncology department filing system at a London hospital into three piles: Living, Dead, Dying. I’ve lugged heavy firecheck doors all around a Hackney warehouse. When my dad was an Investigator for a security firm back in the late ’80s and early ’90s, I was offered the chance to spend my summers between college and university terms working as a security guard, usually on a construction site, for £2.50 an hour (thanks, Dad… why couldn’t you have been a chocolate taster, or the owner of a boutique hotel?). Invariably this would involve sitting in a Portakabin or, if I was unlucky, a car, for up to 16 hours a day, mainly ensuring that kids didn’t come to play in the piles of sand.

One summer I wrote the first draft of a novel and soaked up a very nice tan while ostensibly acting as a deterrent in serge on a patch of waste land off the M56 near Appleton. With hindsight I was lucky to have that job, even though it didn’t pay well, because it gave me huge swathes of time to write, or read, with impunity. I wanted to do nothing but be a writer, and I remember being in a froth of panic at the thought that one day I would probably end up with a proper job that stole the hours I would otherwise spend making things up.

When I did get a proper job, my fears came true and I grew so desperate to get my own fiction written that I set the alarm clock for 6am so I could get some pages down before I went into work.

Now I’ve been lucky enough to write full time for a few years. It’s likely not to be a permanent thing, but I’ll take it where I can. It’s all I really know and what I love. I imagine this cycle of writing and work will continue until I’m too decrepit to know the difference between a pen and a mug of Complan (if indeed I ever did). Essentially, I couldn’t stop writing even if I wanted to. It is as much a part of me as my heart or my backbone. I was writing before I realised you could be paid for it, and I think that is key to the kind of writer you eventually become.

Which brings me, somewhat circuitously, to the point of this post. In recent times I’ve stumbled upon (what I consider) strange behaviour among established writers, chiefly Jim Crace and Alice Munro. Both have taken the decision to retire from writing, as if it was, you know, just a normal job and not some ravening compulsion. Crace, clearly, is not what you might call a born writer. He considers writing to be something one should be paid to do and believes that once your popularity wanes, you should pack it in. In an interview in 2008 with the Guardian, Crace first broached the subject of his own retirement. An author’s lot is predicated on bitterness, according to him, resulting in “the elderly novelist who may be writing his/her best books but whose day has come and gone. S/he is no longer fashionable and can only find a marginal publisher and command a tiny advance. The book receives few reviews and is ignored by the public. Bitterness.”

Munro’s situation is all the more baffling because previously, in a Paris Review interview, she’d expressed concern at the thought of calling it a day. You get the sense, though, with Munro (who is 81 compared with Crace, in his mid-sixties), that she feels she’s written everything she wanted to write, that she is, in effect, spent. If that’s the case, then good luck to her. I hope to hell that never happens to me.

I contacted two writers I admire immensely – Ramsey Campbell and Peter Straub – both huge influences on me as I was developing, and both of an age that in other occupations would see them being handed the gold carriage clock and a goodbye handshake, yet both are still going strong.

Ramsey is as prolific as ever, perhaps even more so. Over a career that spans fifty years, he has published such genre classics as The Face that Must Die, Incarnate, Midnight Sun and The Grin of the Dark as well as hundreds of short stories. This year sees the publication of The Last Revelation of Gla’aki, which is, unless I’m mistaken, his 33rd novel.

Photo: Peter Coleborn

“I can’t imagine ever retiring as a writer unless that was somehow enforced, say by an illness that left me unable to write,” Ramsey says. “Ideas – I have notebooks full of them, and some have been lying dormant for years, even decades. Now and then I have a browse of them and often discover how to develop one that failed to inspire me at the time. Not long ago I discovered that my original notes that led to my writing ‘The Companion’ forty years ago are so remote from the actual story that there’s actually a complete other tale to be had of them, and I may well get around to it. As to the future, well, they’d better leave me a pen inside the coffin in case I need to scribble a last tale or two.”

Peter Straub, arguably one of the most influential modern horror writers, is the author of Ghost Story, Shadowland, Floating Dragon and Koko. Recent books such as lost boy, lost girl and In the Night Room have garnered awards and critical acclaim. His latest novel, A Dark Matter, was described by the Guardian as ‘understated, literary horror, all the more terrifying… for what he keeps from the reader and for his brilliant psychological portraits of innocents caught up in events beyond their control and understanding. Gripping.’

Photo: Kyle Cassidy

“I’ve never thought for longer than a couple of seconds about retirement,” says Peter, “but Philip Roth retired this year, and if he can do it, I certainly can. I guess the real motive would arrive one day when I would have to realize that I really was not as good as once I was, and my books really did seem to be growing weaker. For long time now, writing fiction has seemed to be my most dependable way of achieving stability, contentment, inner peace. Yet now I am seventy, and writing has become more difficult, and it goes a lot more slowly. I’d like to think I might have three or four more novels in me. The presence of ideas or the lack of ideas does not trouble me, because I almost never have ‘ideas’. I spin everything out of its own materials. This is a very absorbing process. However, the certainty of embarrassing myself in public would be a powerful incentive to walk away from my desk.

“I don’t think one can think of writing in the same way one would medicine or the law, or any conventional business. It is riskier and scarier, also less tangible than most occupations. And you have to spend so much time alone. It is a very strange, small, displaced aperture through which to see and experience the world, also to explain what you find in the process. On the other hand, it is so unimaginably rich.”

Ten years ago I interviewed Christopher Priest, and at the time he said something about writing that resonated with me. He said writing was like ‘drinking water’. It was just something he did, natural and essential to his life. He could no longer stop doing it than he could stop breathing. And most writers I know feel the same way. Because how do you switch off the tap? Or is it a case of no longer answering the ‘What if?’ questions, ignoring the moments when you think: that would make a good story. Turning away from the fantasies, refusing to engage with the voices in your head – to me (at the moment) that sounds more like death than the real thing.

June 22, 2013

Doorstep Horror

This post originally appeared at the Mulholland Books website in September 2010, shortly before my crime novel, Blonde on a Stick, was published.

October 1977. I’m eight years old. Dad’s at work. I’m sitting at home hunched over a chessboard waiting for him. White and black plastic. Pawns and pieces on a foldout board fraying at the edges and along the central crease. Knights in profile facing the King and Queen. I’ve been teaching him to play.

A radio on in the kitchen. Mum’s getting ready to go out. She has a part-time job at the Imperial pub on Bewsey Road, a five-minute walk away, serving pints of mixed and pints of tan and black to wire-factory workers: No-Danger Joe, who has his own chair by the door. Nodding Kenny, who’ll agree with anything his boss says. Varley, the pisshead with eyes the color of verdigris, trying it on with the barmaids. She serves them all until they’re too drunk to speak, at which point the manager, a gruff Belfastard, points to the door.

Dad works at the police station in Chester. Top floor. I’ve been to the canteen there. You can look out at the river Dee and the Roman wall while you eat your pie and mash and tea (two sugars). This was in the days before healthy eating. Healthy anything. This was smoker’s cough with your cake and a pall of undigested whisky fumes at breakfast. Bring the lad in to work for the morning. Nice treat while Mum’s in hospital. The receptionist — Brenda or Beryl or Olive — asks if I want a Quality Street sweet while I hide behind Dad’s legs. He’s all smiles and muttonchop whiskers. The clatter of typewriters vibrates through the building. I can smell carbon paper and Quink ink and wet dog and leather. Hoops of sweat under armpits, rings of grime on loosened collars. Brylcreemed hair and Hamlet cigars in top pockets. The world is filled with villains and slags and bastards. Some of them work here.

That radio. Chat and comment and opinion. All buzz. All background. Dad comes in. Winter’s breath full of bonfires and petrol fumes. Kiss, kiss. Dinner’s in the oven, cold lips. Mum goes out into crystallizing darkness. Dad and his brown, steaming hot pot, slashed through with red cabbage. I can’t look at his plate. Newspapers. Can of beer. I wait. I listen. Newsflash. This just in. The body, as yet unidentified, was found on wastelands behind Manchester’s southern cemetery…

Dad puts his fork down. On the phone. He’s here then, he says. He’s come over to Manchester.

I know he’s talking about the Ripper. It’s all you hear about in the school playgrounds. Brian Trent got into trouble with the headmistress for starting a game called Dead, where he pretended to be Jack, felling girls, and how many could he get on the floor before the coppers stopped him? Manchester is twenty miles from here. If the Ripper can leave his hunting grounds of Bradford and Leeds to travel across the Pennines, then he can nip along the M62 to Warrington. Mum will walk home alone this night.

This is where much of it started for me, this business of horror and crime. Siamese genres that share the same diabolical heart. A faceless killer with a northern accent. Pictures of policemen on their knees in allotments and alleyways combing the area for clues. Everything black and cold and filthy. Desperate women torn apart on cobblestones. Doorstep horror. A wraith evading capture and grinning at the plods in their abject failure.

My parents were both in the police force. Mum left when she became pregnant with me. Good was instilled in me as intractably as the marrow in my greenstick bones. I behaved. I was shy to the point of becoming wallpaper. Spock hair. National Health Service glasses. If it weren’t for the blue serge and silver pips in my family I’d have been bully fodder. As it was, I was overlooked. I witnessed casual violence in the playground, observed the rhythms and reactions. I learned about preemptive strikes, grudges, breaking points. Some of these kids would go on to be ugly criminals. There was a rapist among them, it turned out. There was a murderer and a victim. It was a rough old school.

I lived in a pub, too. Once Dad had finished his twenty-five-year stint and picked up his carriage clock and index-linked pension, he did the usual where bobbies were concerned and took over management of the Wheatsheaf Hotel on Orford Lane. What might a quiet boy deep into solitude see here? Time, gentlemen, please. Gentlemen. Oh, really? I’ve seen drunk men threaten each other with the bare fangs of broken beer glasses. Hiked skirts, dirty thumbs hooking into knicker elastic against back alley garbage hoppers. Dad with a black eye and a split lip thanks to a “gentleman” who took umbrage at a request to drink up now, please.

I found echoes of all of this in the black novels of Derek Raymond and waded into the filth after the unnamed Detective Sergeant to the dank, stinking hellholes where bad men met their ends. I fell for the grand guignol of Thomas Harris’s Red Dragon and the existential tension in James Sallis’s Death Will Have Your Eyes. Later, David Peace’s Red Riding Quartet, which was punishing but magnificent, offering up great swathes of my own childhood panic in its red, steaming fists.

All of this has directed where I go in everything I write, but most of it comes from the lonely places from which I viewed the world, and those that I disappeared to inside myself.

Eight years old and I wanted to make sure Mum would be all right walking across Lovely Lane at closing time. Imagining her wrapped in her coat, chilled by that Warrington winter, while fear, and maybe something else, hastened her heels. It still frightens me now. More so than the endless scrutiny of faces as men poured out of the factories at quitting time : Is it him? Is it him? Is it him? More than the “I’m Jack” tape. More than the conjecture about what the Ripper did to his victims in the blanket secrecy — details jealously kept by the police — that followed his attacks.

People ask me why I’ve made the transition from horror to crime and I think: “Transition? Seriously? What the hell are you talking about?”

June 21, 2013

My Top Ten non-horror films #6

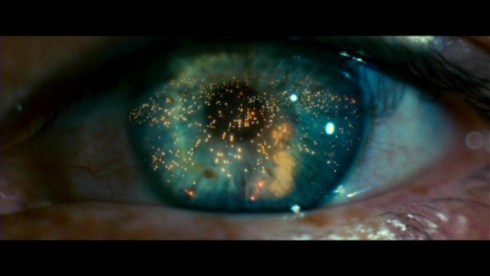

6 – BLADE RUNNER (1982)

Forget the cliché-ridden voiceover that sounded as if it was phoned in by Harrison Ford. Forget too the happy ending with its bolted-on footage from The Shining. Go for the Director’s Cut. Lean, moody, brutal and brilliant. SF-noir at its most seductive: grimily gorgeous, with a match-made-in-heaven score by Vangelis. I remember being too young to see this at the cinema when it was on at the ABC in Warrington, but I was smitted by the poster (Han/Indy was in it!) and stared at it every time we drove past, desperate to know what the film was about. Quite how it wasn’t a massive hit from day one perplexes me. Maybe early 80s Britain, bruised and battered after the riots and a pervasive mistrust of the police, wasn’t ready for that kind of reflective vision. Not so much futuristic as right here, right now, or at least a glimpse at the shape of things to come.