Mark Winborn's Blog, page 7

March 2, 2014

Massimo Giannoni: Relational Aspects of Analytical Psychology

"We can pose for analytical psychology two fundamental questions that Greenberg and Mitchell (1983)have already posed for other psychoanalytic theories: (1) What is the main goal and motivation behind human action? (2) Does analytical psychology contain a two-person or a one-person conception of therapy and of development?

The first question is easy to answer. The main motivation for human action postulated by Jung is a striving for self-realization, presupposing an innate capacity for the self-regulation of the psychic apparatus analogous to that which has been called “self-righting” by Lichtenberg, Lachmann, and Fosshage (1996). This commonality contributes to the indubitable affinities that can be seen between certain aspects of analytical psychology and self psychology (Jacoby, 1990; Fosshage, 2000). This “individualizing” motivation, as presented by Jung, has received some confirmation in empirical research (Lichtenberg, 1983; Stern, 1985, 1995) and is in harmony with some post-Freudian psychoanalytic theories, for example, those of Guntrip (1961), Kohut (1984), and Winnicott (1989). In the past, the Jungian hypothesis of a fundamental motivation toward the development of the self was in sharp contrast with classical Freudian theory, which hypothesized sex and aggression as primary drives in conflict with the environment (Giannoni, 1999). Today this theoretical aspect of Jungian psychology not only does not prevent a dialogue with contemporary psychoanalysis, but rather facilitates it, especially with self-psychology (Giannoni, 2003).

The second question, whether analytical psychology adopts a one-person or a two-person conception of the development and therapy, is a more difficult and controversial one. In many writings Jung (1931, 1935a, 1946) stated that therapy is certainly interactive and that the involvement of the analyst is indispensable. The concept of “psychic contagion” is presented as prerequisite to any real change in the patient, and the psychotherapeutic relationship is compared to the

Alongside this two-person aspect of Jung's idea of transference we find a markedly one-person theoretical conception of the development. Jung's theory of development, called individuation, states that a person develops his own individuality according to a predetermined plan within himself and without any particular environment responsiveness (Jacoby, 1990; Fosshage, 2002); Jung (1943)said: “The meaning and purpose of the process is the realization, in all its aspects, of the personality originally hidden away in the embryonic germ-plasm; the production and unfolding of the original, potential wholeness” (p. 110). We can answer the second question by asserting that both options (two-person and one-person) are present in Jung. Moreover, Jung's theory of development contains many one-person elements, whereas his clinical practice is more relational (Giannoni, 2000)—this gap between theory and clinical practice warrants further investigation." (pp. 608-609)

Massimo Giannoni (2003). Jung's Theory of Dream and the Relational Debate. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, Vol. 13, pp. 605-621

The first question is easy to answer. The main motivation for human action postulated by Jung is a striving for self-realization, presupposing an innate capacity for the self-regulation of the psychic apparatus analogous to that which has been called “self-righting” by Lichtenberg, Lachmann, and Fosshage (1996). This commonality contributes to the indubitable affinities that can be seen between certain aspects of analytical psychology and self psychology (Jacoby, 1990; Fosshage, 2000). This “individualizing” motivation, as presented by Jung, has received some confirmation in empirical research (Lichtenberg, 1983; Stern, 1985, 1995) and is in harmony with some post-Freudian psychoanalytic theories, for example, those of Guntrip (1961), Kohut (1984), and Winnicott (1989). In the past, the Jungian hypothesis of a fundamental motivation toward the development of the self was in sharp contrast with classical Freudian theory, which hypothesized sex and aggression as primary drives in conflict with the environment (Giannoni, 1999). Today this theoretical aspect of Jungian psychology not only does not prevent a dialogue with contemporary psychoanalysis, but rather facilitates it, especially with self-psychology (Giannoni, 2003).

The second question, whether analytical psychology adopts a one-person or a two-person conception of the development and therapy, is a more difficult and controversial one. In many writings Jung (1931, 1935a, 1946) stated that therapy is certainly interactive and that the involvement of the analyst is indispensable. The concept of “psychic contagion” is presented as prerequisite to any real change in the patient, and the psychotherapeutic relationship is compared to the

Alongside this two-person aspect of Jung's idea of transference we find a markedly one-person theoretical conception of the development. Jung's theory of development, called individuation, states that a person develops his own individuality according to a predetermined plan within himself and without any particular environment responsiveness (Jacoby, 1990; Fosshage, 2002); Jung (1943)said: “The meaning and purpose of the process is the realization, in all its aspects, of the personality originally hidden away in the embryonic germ-plasm; the production and unfolding of the original, potential wholeness” (p. 110). We can answer the second question by asserting that both options (two-person and one-person) are present in Jung. Moreover, Jung's theory of development contains many one-person elements, whereas his clinical practice is more relational (Giannoni, 2000)—this gap between theory and clinical practice warrants further investigation." (pp. 608-609)

Massimo Giannoni (2003). Jung's Theory of Dream and the Relational Debate. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, Vol. 13, pp. 605-621

Published on March 02, 2014 10:33

March 1, 2014

Conference: Ronald Fairbairn and the Object Relations Tradition

Space still available for participation by video link:

Ronald Fairbairn and the Object Relations Tradition

At the Freud Museum London 7th - 9th March 2014 Registrations for the full conference have sold out, but a limited number of discounted tickets are now available for a video link room. The presentations will be relayed on a screen in a room above the main conference room. The tickets include tea and coffee breaks and the reception at the Freud Museum on Saturday evening. The cost is £100 and £80 (plus £10 / £5 reduction for members of the Freud Museum, IPI and Essex University). Only weekend tickets are available.For more information, or to register: http://www.freud.org.uk/events/75383/ronald-fairbairn-and-the-object-relations-tradition/

Ronald Fairbairn was the father of object relations theory, which now permeates modern psychoanalytic thought. He developed a distinctive psychology of dynamic structure that began with the infant's need for relationships, and in which mental structure is based upon the relations between ego-structures and the internal objects that result from introjection and psychic modification of these early relationships. This conference will outline the basics of Fairbairn's contribution, and then explore the ramification and development of these ideas to clinical work, and broadly to applications in modern psychoanalytic thinking.

Friday March 7 Opening Panel: Internalization and the Status of Internal Objects Norka Malberg: On Being Recognized Viviane Green: Internal objects: Fantasy, Experience and History Intersecting?David Scharff: Internal Objects and External Experience Saturday, March 8 Presentations and Discussion Marie Hoffman: Fairbairn and Religion James Poulton: Philosophical Foundations of Fairbairn Gal Gerson: Hegelian Themes in Fairbairn's WorkSteven Levine: Fairbairn's Theory of the Visual Arts and its Influence Johnathan Sklar: Discussion of Steven Levine's PresentationJoseph Schwartz: Fairbairn and the Good Object: A bone of contention Molly Ludlam: Fairbairn and the Couple - Still a Creative Threesome?Jill Scharff: Fairbairn's Clinical Theory Panel: Psychic Growth Lesley Caldwell: Being at Home with One's Self: the Condition of Psychic Aliveness?Anne Alvarez: Paranoid-Schizoid Position or Paranoid and Schizoid Positions?Graham Clarke: Psychic Growth and Creativity Wine and Cheese Reception Fairbairn and the Object Relations Tradition (Karnac Books) on sale in museum shop Sunday, March 9 Presentations and Discussion Eleanore Armstrong-Perlman: The Zealots and the Blind: Sexual Abuse Scandals from Freud to Fairbairn Carlos Rodriguez-Sutil: Fairbairn's Contribution to Understanding Personality Disorders Valerie Sinason: Abuse, Trauma and Multiplicity Ruben Basili: Recent Work from Argentina's Espacio Fairbairn Video Reflections on Fairbairn from Otto Kernberg and John Sutherland Hilary Beattie: Fairbairn and Homosexuality: Personal Struggles amid Psychoanalytic Controversy Panel: Groups, Social Issues and the Social Unconscious Earl Hopper, Chair and Discussant Julian Lousada: Psychoanalysis Goes to Market ?Stephen Frosh: What Passes, Passes By: Why the Psychosocial is Not (Just) RelationalRon Aviram: The Large Group in the Mind (With Special Reference to Prejudice, War, and Terrorism) Closing Group Discussion Graham Clarke, Ivan Ward and David Scharff, Co-Chairs

[image error]

[image error]

Published on March 01, 2014 12:15

February 12, 2014

Jung and Lacan Conference - September 2014

A Joint Jung/Lacan ConferenceSt John's College Cambridge, UK

Friday 12th – Sunday 14th September 2014The Notion of the Sublime

in Creativity and DestructionConvenors: Lionel Bailly, Bernard Burgoyne, Ann Casement, Phil Goss

One hundred years since the outbreak of The Great War, which radically changed many of the western world's rational values and belief systems, this conference brings together scholars and psychoanalysts from different disciplines to explore, through a depth psychological lens, the forces of creativity and destruction enshrined in the notion of the sublime.Conference to include: Keynote Lectures

Papers by Delegates

Breakout Sessions

PostersFurther information of programme details will be available from the end of March 2014 from prbd.4469@gmail.com

Friday 12th – Sunday 14th September 2014The Notion of the Sublime

in Creativity and DestructionConvenors: Lionel Bailly, Bernard Burgoyne, Ann Casement, Phil Goss

One hundred years since the outbreak of The Great War, which radically changed many of the western world's rational values and belief systems, this conference brings together scholars and psychoanalysts from different disciplines to explore, through a depth psychological lens, the forces of creativity and destruction enshrined in the notion of the sublime.Conference to include: Keynote Lectures

Papers by Delegates

Breakout Sessions

PostersFurther information of programme details will be available from the end of March 2014 from prbd.4469@gmail.com

Published on February 12, 2014 05:00

February 10, 2014

Analysis and Activism in Analytical Psychology - Conference December 2014

International Association for Analytical Psychologywith Association of Jungian Analysts, British Jungian Analytic Association, Guild of Analytical Psychologists, Independent Group of Analytical Psychologists, Society of Analytical PsychologyCONFERENCEANALYSIS AND ACTIVISM: SOCIAL AND POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS OF JUNGIAN PSYCHOLOGY Friday December 5th 2014 (6pm wine and canapés reception, 7.30-10pm conference)Saturday December 6th (9.30am-7.00pm)Sunday December 7th (2.30pm finish)Venue: Wesley Ethical Hotel and Conference Centre, 81-103 Euston Street, London NW1 2EZ, UKwww.thewesley.co.ukJungian psychology has taken a noticeable 'political turn' in the past twenty years. Analysts and academics whose work is grounded in Jung's ideas have made internationally recognised contributions in many areas. These include: psychosocial and humanitarian interventions, conflict resolution, ecopsychology, issues affecting indigenous peoples, prejudice and discrimination, leadership and citizenship, social inclusion, and economics and finance.The conference will be of interest to activists, concerned citizens and academics - as well as to the whole range of clinical disciplines, whether Jungian or not. We particularly welcome students and trainees. It is the first occasion on which these contributors have been brought together from many countries specifically to address many of the most pressing crises and dilemmas of our time.Speakers include: Lawrence Alschuler (Canada), John Beebe (US), Astrid Berg (South Africa), Jerome Bernstein (US),Walter Boechat (Brazil), Stefano Carta (Italy), Angela Cotter (UK), Peter Dunlap (US), Roberto Gambini (Brazil), Gottfried Heuer (UK), Toshio Kawai (Japan), Tom Kelly (Canada), Sam Kimbles (US), Tom Kirsch (US), Ann Kutek (UK), Kevin Lu (UK), Francois Martin-Vallas (France), Renos Papadopoulos (UK), Eva Pattis-Zoja (Italy), Joerg Rasche (Germany), Susan Rowland (US), Mary-Jayne Rust (UK), Craig San Roque (Australia), Andrew Samuels (UK), Heyong Shen (China), Tom Singer (US), Tristan Troudart (Israel), Luigi Zoja (Italy).A few words from Conference Organisers Emilija Kiehl and Andrew Samuels about their vision for the Conference: https://vimeo.com/85523121Full conference fee: £130 (SFR 196)Early bird full fee to end of July 2014: £110 (SFR 165)Concession fee (students and unwaged): £95 (SFR 142)Early bird concession fee to end of July 2014: £80 (SFR 120)For registration and hotel accommodation information: http://www.britishpsychotherapyfoundation.org.uk/BJAA/bjaa-eventsSpace is limited – early booking advised

Published on February 10, 2014 05:00

February 9, 2014

Judith L. Mitrani - 'Taking the Transference' vs. Desire to do Good

"In concluding, I wish to express my belief that many of us are drawn to the work of analysis, at least in part, by the desire to do some good. However, paradoxically, this may be the greatest obstacle to actually doing ‘good analytic work’ and therefore the greatest barrier to truly helping the patient. If unbridled, it may prove to be the most obstructive ‘desire'—in Bion's sense of the word—since our patients may actually need to transform us, in the safety of the transference relationship, into the ‘bad’ object that does harm. In terms of analytic technique, the analyst needs to be able to muster the wherewithal to see, hear, smell, feel and taste things from the vantage point of the patient. I have found it is of little use to give the patient the impression, in one way or another, that what he/she made of what I said or did was neither what I intended nor what I actually did or said. This tactic almost always misses the point and may even reinforce the patient's sense that his/her experiences are indeed unbearable.

Our analysands’ developmental need to house their ‘bad’ objects and unendurable experiences in us is primary. Within us, these objects and the experiences that have created them may find an opportunity for rehabilitation and transformation. For example, the experience of the ‘abandoning object’ that we become—during holidays, weekend breaks, silences and especially in the absence of our understanding in the analytic hour—may have the chance to become an experience of ‘an abandoning object who takes responsibility for having abandoned the patient’ and who, at the same time, is able to keep the patient in mind sufficiently to be able to think about how he/she might feel about having been abandoned. Most importantly, that same object may also be experienced by the patient as able to bear being ‘bad’, which in itself is ‘good'! Furthermore, when reintrojected by the patient in this modified form, the ‘bad’ object is not so ‘bad’ at all: it is human, ordinary with all the ordinary human frailties imaginable, but it is bearable. In this transformed stare, the ‘bad’ object (which is now the contained) is enhanced with a ‘container’ (the analytic object), and the patient will be well on his way towards ‘being’ a thinking and feeling individual." (p. 1102)

Judith L. Mitrani, (2001). ‘Taking the Transference’. Int. J. Psycho-Anal., Vol. 82, pp. 1085-1104

Our analysands’ developmental need to house their ‘bad’ objects and unendurable experiences in us is primary. Within us, these objects and the experiences that have created them may find an opportunity for rehabilitation and transformation. For example, the experience of the ‘abandoning object’ that we become—during holidays, weekend breaks, silences and especially in the absence of our understanding in the analytic hour—may have the chance to become an experience of ‘an abandoning object who takes responsibility for having abandoned the patient’ and who, at the same time, is able to keep the patient in mind sufficiently to be able to think about how he/she might feel about having been abandoned. Most importantly, that same object may also be experienced by the patient as able to bear being ‘bad’, which in itself is ‘good'! Furthermore, when reintrojected by the patient in this modified form, the ‘bad’ object is not so ‘bad’ at all: it is human, ordinary with all the ordinary human frailties imaginable, but it is bearable. In this transformed stare, the ‘bad’ object (which is now the contained) is enhanced with a ‘container’ (the analytic object), and the patient will be well on his way towards ‘being’ a thinking and feeling individual." (p. 1102)

Judith L. Mitrani, (2001). ‘Taking the Transference’. Int. J. Psycho-Anal., Vol. 82, pp. 1085-1104

Published on February 09, 2014 11:20

February 8, 2014

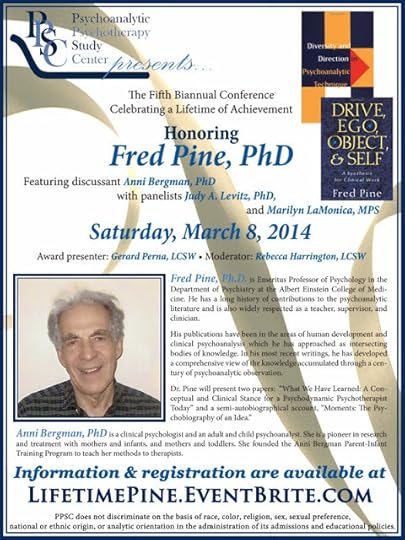

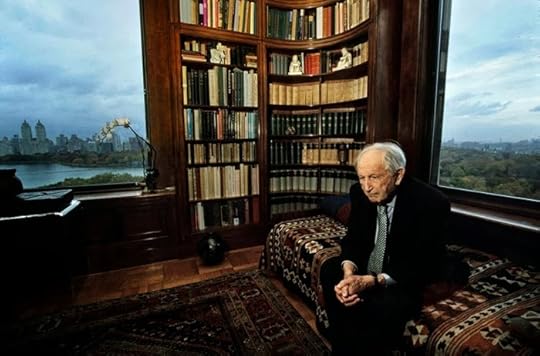

PPSC Honors Fred Pine, PhD on March 8, 2014 in NYC

Published on February 08, 2014 06:00

February 3, 2014

Erel Shalit - On Self and Meaning in the Cycle of Life

In old age, hearing becomes impaired and vision more blurred. For some, this provides an opportunity to open the senses to the pulsation of the soul, to hear the echoes of the sounds that arise from the depths, and perceive the reflection of the patterns that take shape under the sea.

This may be the transparency and the invisibility of not being seen by others, and the fear of being run over by the phenomena, the appearances of this world. However, as has been mentioned, it entails exchanging the reality-oriented ego-vision for the inward gaze—like Oedipus upon tearing out his eyes, and the seer Tiresias, or Samson. When blinded to this world of appearance, the inner world of transparent, invisible psychic substance may open up, to be sighted. This change in the ego-Self relationship marks a release of the ego from the persona of social roles. It is the invisibility of allowing oneself to be a beggar, a wanderer, or an old fool—not in the social, but in the psychological sense.

In order to attain a sense of integrity in old life, rather than suffer severe despair, Erikson emphasizes the importance of reflection. The reflective instinct is specifically human, and determines “[t]he richness of the human psyche and its essential character,” says Jung. Reflexio, which

means ‘bending back,’ “is a turning inwards, with the result that, instead of an instinctive action, there ensues ... reflection or deliberation.”

“What youth found and must find outside,” says Jung, “the man of life’s afternoon must find within himself.” Jung calls reflection “the cultural instinct par excellence.” Reflection on one’s life is instrumental at every developmental stage, unless it takes precedence over living one’s life. In

old age, the proportions alter, so that reflection on one’s life becomes at least as important as merely living it.

When cut off from one’s inner depths, the personality shrinks as the ego dries up and becomes limited. A reflective state of mind, however, enables the depths to be reflected in the mirror of one’s Self and soul. Henry Miller tells us in Colossus of Maroussi that he did not know the meaning of

peace until he visited the principal sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidaurus, where dream incubation began around 600 BCE. In the intense stillness and the great peace at Epidaurus “I heard the heart of the world beat. I know what the cure is: it is to give up, to relinquish, to surrender, so that our little hearts may beat in unison with the great heart of the world.” Henry Miller makes it clear that Epidaurus, principally, is an internal space, “the real place is in the heart, in every man’s heart, if he will but stop and search it.”

Reflection and imagination constitute the intangible substance of soul, which Hillman suggests refers “to that unknown component which makes meaning possible,” and which he imagines “like a reflection in a flowing mirror.” (p. 177-8)

Erel Shalit (2011) The Cycle of Life: Themes and Tales of the Journey, Fisher King Press.

Dr. Shalit's most recent work is The Dream and its Amplification, Erel Shalit & Nancy Swift Furlotti, eds. (2013, Fisher King Press).

This may be the transparency and the invisibility of not being seen by others, and the fear of being run over by the phenomena, the appearances of this world. However, as has been mentioned, it entails exchanging the reality-oriented ego-vision for the inward gaze—like Oedipus upon tearing out his eyes, and the seer Tiresias, or Samson. When blinded to this world of appearance, the inner world of transparent, invisible psychic substance may open up, to be sighted. This change in the ego-Self relationship marks a release of the ego from the persona of social roles. It is the invisibility of allowing oneself to be a beggar, a wanderer, or an old fool—not in the social, but in the psychological sense.

In order to attain a sense of integrity in old life, rather than suffer severe despair, Erikson emphasizes the importance of reflection. The reflective instinct is specifically human, and determines “[t]he richness of the human psyche and its essential character,” says Jung. Reflexio, which

means ‘bending back,’ “is a turning inwards, with the result that, instead of an instinctive action, there ensues ... reflection or deliberation.”

“What youth found and must find outside,” says Jung, “the man of life’s afternoon must find within himself.” Jung calls reflection “the cultural instinct par excellence.” Reflection on one’s life is instrumental at every developmental stage, unless it takes precedence over living one’s life. In

old age, the proportions alter, so that reflection on one’s life becomes at least as important as merely living it.

When cut off from one’s inner depths, the personality shrinks as the ego dries up and becomes limited. A reflective state of mind, however, enables the depths to be reflected in the mirror of one’s Self and soul. Henry Miller tells us in Colossus of Maroussi that he did not know the meaning of

peace until he visited the principal sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidaurus, where dream incubation began around 600 BCE. In the intense stillness and the great peace at Epidaurus “I heard the heart of the world beat. I know what the cure is: it is to give up, to relinquish, to surrender, so that our little hearts may beat in unison with the great heart of the world.” Henry Miller makes it clear that Epidaurus, principally, is an internal space, “the real place is in the heart, in every man’s heart, if he will but stop and search it.”

Reflection and imagination constitute the intangible substance of soul, which Hillman suggests refers “to that unknown component which makes meaning possible,” and which he imagines “like a reflection in a flowing mirror.” (p. 177-8)

Erel Shalit (2011) The Cycle of Life: Themes and Tales of the Journey, Fisher King Press.

Dr. Shalit's most recent work is The Dream and its Amplification, Erel Shalit & Nancy Swift Furlotti, eds. (2013, Fisher King Press).

Published on February 03, 2014 17:33

February 2, 2014

C.G. Jung's Collected Works Available in Digital March 1st

For the first time, The Collected Works of C. G. Jung will now available in English as individual e-books and as a complete digital set. Both the individual volumes and the set are fully searchable.The main volumes, Vols. 1-18, are available for individual purchase.The set--available at a special introductory list price of $499 ($399 when pre-ordered through Amazon) - includes Vols. 1-18 and Vol. 19, the General Bibliography of C. G. Jung’s Writings. (It excludes Vol. 20, the General Index to the Collected Works.). http://www.amazon.com/The-Collected-Works-C-G-Jung-ebook/dp/B00HQPHACS/ref=sr_1_6?ie=UTF8&qid=1391194095&sr=8-6&keywords=collected+works+of+cg+jung

Published on February 02, 2014 20:16

January 27, 2014

New York Psychoanalyst Martin Bergmann Dies at 100

Details of Dr. Bergmann's life and analytic career available at the New York Times link below.

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/27/movies/martin-s-bergmann-psychoanalyst-and-woody-allens-on-screen-philosopher-dies-at-100.html?_r=0

Published on January 27, 2014 19:39

January 15, 2014

Paul Ashton - Experiences of the Void

“A commonly encountered experience of both analyst and analysand is that of the void. It is spoken about at different stages of therapy and refers to experiences that have different origins. Sometimes the experience of the void is around a relatively limited aspect of the psyche but at other times the void seems much more global and threatens to engulf the entire personality; the whole individual psyche then seems threatened by the possibility of dissolution into nothingness.

The void experience may result from the early failure of external objects to meet the needs of the developing ego, which leads to the sorts of primitive terrors that Winnicott described, or it may result when the Self itself seems threatened with annihilation, which may be more to do with a rupturing of the ego–Self axis. In the first case the fear is of disintegration, whereas in the second the experience is one of the living dead, as though the individual is cut off from her life source. But more than that, the intrusion of the void into the conscious experience of so many of us implies that its occurrence is not only the result of severe trauma but also a necessary aspect of the individuation process.

Drawing on the writings of Jung and post-Jungians, and psychoanalytic thinkers such as Bion, Winnicott, and Bick, as well as on poetry, mythology, and art, and illustrating these ideas with dreams and other material drawn from my practice, I hereby attempt to illuminate some of the compartments of this immense space. As Estragon comments, in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, “there is no lack of void”, and this book looks at the genesis of this state in the individual in both its pathological and life-enhancing aspects.

In certain of the void states, particularly those arising from severe trauma, memories of past events have disappeared as though sucked into a black hole. In others it is the emergence of the psyche into the white light of a higher consciousness that may be experienced in a threatening way. To feel the presence of the void is to reach the edge of the known world, inner or outer. It is a liminal state that extends backwards from the far side of memory yet continually emerges from the forward edges of our experience. It is by nature frightening and, usually, well defended against.

…My thesis is that the void, frightening as it is, is not something that can or should be obliterated, as that would lead to stagnation. Rather, that hidden behind the “clouds of unknowing” (Bion, 1967) that shroud the void, lie endless possibilities for growth and transformation and an increasingly strong connection with the objective other. It has seemed to me that the void experience in childhood and early adulthood is mostly associated with fear and can be deemed pathological. In order for the ego to learn to stand alone it appears that it has to deny, or live as though unaware of, the existence of the void. When the void is constellated in these individuals it is often defended against rigidly and what seems to be necessary is to help them find structure and meaning in their lives, i.e. non-void attributes.” (p. 1-2)

Ashton, Paul W. (2007) From the Brink: Experiences of the Void from a Depth Psychology Perspective, London: Karnac.

The void experience may result from the early failure of external objects to meet the needs of the developing ego, which leads to the sorts of primitive terrors that Winnicott described, or it may result when the Self itself seems threatened with annihilation, which may be more to do with a rupturing of the ego–Self axis. In the first case the fear is of disintegration, whereas in the second the experience is one of the living dead, as though the individual is cut off from her life source. But more than that, the intrusion of the void into the conscious experience of so many of us implies that its occurrence is not only the result of severe trauma but also a necessary aspect of the individuation process.

Drawing on the writings of Jung and post-Jungians, and psychoanalytic thinkers such as Bion, Winnicott, and Bick, as well as on poetry, mythology, and art, and illustrating these ideas with dreams and other material drawn from my practice, I hereby attempt to illuminate some of the compartments of this immense space. As Estragon comments, in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, “there is no lack of void”, and this book looks at the genesis of this state in the individual in both its pathological and life-enhancing aspects.

In certain of the void states, particularly those arising from severe trauma, memories of past events have disappeared as though sucked into a black hole. In others it is the emergence of the psyche into the white light of a higher consciousness that may be experienced in a threatening way. To feel the presence of the void is to reach the edge of the known world, inner or outer. It is a liminal state that extends backwards from the far side of memory yet continually emerges from the forward edges of our experience. It is by nature frightening and, usually, well defended against.

…My thesis is that the void, frightening as it is, is not something that can or should be obliterated, as that would lead to stagnation. Rather, that hidden behind the “clouds of unknowing” (Bion, 1967) that shroud the void, lie endless possibilities for growth and transformation and an increasingly strong connection with the objective other. It has seemed to me that the void experience in childhood and early adulthood is mostly associated with fear and can be deemed pathological. In order for the ego to learn to stand alone it appears that it has to deny, or live as though unaware of, the existence of the void. When the void is constellated in these individuals it is often defended against rigidly and what seems to be necessary is to help them find structure and meaning in their lives, i.e. non-void attributes.” (p. 1-2)

Ashton, Paul W. (2007) From the Brink: Experiences of the Void from a Depth Psychology Perspective, London: Karnac.

Published on January 15, 2014 06:00