Terry Farish's Blog, page 28

November 17, 2012

The Verse Novel: Pat Lowery Collins

hoping, like a hiding child, that if

I do not look into each face,

I cannot then be seen.”

“Braiding the Verse Novel” is a series of interviews I did with writers of novels in verse. We had our conversations over the summer of 2012. I’ve written articles about verse novels for School Library Journal and NH Writer which draw on these conversations in different ways. Here, I’m posting the generous responses from each of the writers who allowed me to ask them questions.

Pat Lowery Collins is a poet, picture book creator, and writer of a number of historical novels. We talked about her novel, The Fattening Hut, a novel in prose poems in which she imagines a culture in which a young girl comes of age. Booklist writes that the novel “raises provocative questions about cross-cultural boundaries and human rights.” Pat teaches in the MFA program at Lesley University.

Terry: Would you select a few lines from a verse and tell about a choice you made in the craft of those lines?

Pat: I had to select more than a few lines to make my point here. This piece is from a place in the book when the men searching for Helen, the protagonist, seem very close to finding her. To speed up the languid overall pace of the book without changing the established rhythm and to create more immediate tension, I introduced action – pelting from the monkeys, the walking back and forth of the men, the threat inherent in the type of weapons they carry. I also include Helen’s bodily reaction to all this.

“I shut my eyes,

hoping, like a hiding child, that if

I do not look into each face,

I cannot then be seen.

This time, I have left nothing at the base.

They walk around within the grove,

startling the young monkeys into

throwing seaside grapes.

As each man tries to dodge the pelts,

he ducks with eyes upon the ground,

and that is how they pass below my tree.

How strange to see them carrying

spears, as if it is wild animals

they seek and not a very frightened girl.

I keep my breathing silent as a thought.”

Pg. 113-114.

Terry: Were there parallels between the form and the culture you created in the novel?

Pat: I hadn’t planned on using the verse form for “The Fattening Hut”. In fact, I wrote three chapters in prose before discovering that the text was setting itself up predominantly in iambs. When I recognized this, it seemed a natural direction for me to go in. However, it did surprise me, as did many other things about those first chapters. I was searching for a voice for Helen that was believable and somewhat foreign in spite of the fact that I had not yet thought through what her ethnicity would be or what island I was placing her on. Since my process is to jump in without all the facts at first in order to get a feel for the story I want to tell and the people who will tell it, this was not an unusual way for me to work. I did wonder, however, if this particular story written in this way would be something that teens would enjoy. When I first learned of the fattening room tradition in Nigeria, I knew I would not be able to write with any authority from a Nigerian perspective, so my task, as I saw it, was to turn the story into science fiction or invent my own tribe, culture, and island. I eventually chose the latter and used the verse form to help craft the tribal speech patterns, establish a rythmic story telling style, and support the overall pace consistent with the day-to-day life of the island culture that I was creating as well as Helen’s slow days in the fattening hut and the long process of her flight away from it.

Terry: Do you think there is a kind of story that is best suited to the verse novel form?

Pat: I hadn’t thought much about it before employing the technique myself. I can see it as being tedious when used in fast paced scenarios. To me it seems to work best for historical fiction such as “Out of the Dust” by Karen Hesse and “Three Rivers Rising” by Jame Richards. I think it’s also a good vehicle for very personal stories such as “Make Lemonade” by Virginia Euer Wolfe.

Terry: What is an ingredient in a verse novel that wins you over, makes you forget you’re reading and slip into that world?

Pat: I think verse that feels closest to everyday speech, which is said to be principally iambic, is the most effective. There is a repetitive, lulling quality to it that we enjoyed as children and readily succumb to. It makes for a very comfortable and familiar reading experience.

November 16, 2012

OD Bonny Writes “A Girl From Juba”

South Sudanese American rapper OD Bonny opened our launch event for The Good Braider on a blustery November night in Maine . Then he stunned us with a new song he has written to tell the story of Viola, the heroine of the novel. OD is still working on the song and is creating a book trailer with scenes from Juba and Portland. Here’s a sneak preview of OD singing A Girl From Juba.The cover song of his new album, Kwo I Lobo Tek stays in my mind. The Portland Phoenix called it “an infectious pop-hip-hop carousel ride.” “Kwo I Lobo Tek” is Acholi, meaning roughly, life is a hard journey. But the song feels like hope.

South Sudanese American rapper OD Bonny opened our launch event for The Good Braider on a blustery November night in Maine . Then he stunned us with a new song he has written to tell the story of Viola, the heroine of the novel. OD is still working on the song and is creating a book trailer with scenes from Juba and Portland. Here’s a sneak preview of OD singing A Girl From Juba.The cover song of his new album, Kwo I Lobo Tek stays in my mind. The Portland Phoenix called it “an infectious pop-hip-hop carousel ride.” “Kwo I Lobo Tek” is Acholi, meaning roughly, life is a hard journey. But the song feels like hope.

November 4, 2012

History in Poems: Jeannine Atkins

Remember one thing — the price of wheat,

the scents of violets, vinegar pie –

and memories jammed behind may unroll like thread off a spool.

Jeannine Atkins’ poems that recreate the lives of people in history are a part of “Braiding the Verse Novel.” These are a series of interviews I did with writers of novels – and this biography - in verse. We had our conversations over the summer of 2012. I’ve written articles about verse novels that draw on these conversations in different ways.

Jeannine Atkins teaches children’s literature at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Among her award-winning books is Borrowed Names, Poems About Laura Ingalls Wilder, Madam C.J. Walker, Marie Curie, and Their Daughters. She is skilled at crafting poems and stories based the facts of the lives of people in history. I invited Jeannine to select a passage from her poems about Laura Engalls Widler and her daughter and describe her process in creating those lines. Here is what she wrote:

Remember one thing — the price of wheat,

the scents of violets, vinegar pie –

and memories jammed behind may unroll like thread off a spool.

The section in Borrowed Names about Laura Ingalls Wilder and her daughter, Rose, chronicles tension between a very capable mother and a daughter who rarely felt she could live up to her mother’s expectations. This is somewhat resolved when Laura is about sixty, and Rose about forty, and they work together on the series of Little House books. Laura provides the history, while Rose did much of the shaping and editing, a collaboration that made me think of quilting and sewing, crafts important to both women, and is suggested by the thread here. The line reinforces the theme of the way memories can separate, heal, and change, and is spoken by a voice that’s neither Laura’s nor Rose’s, suggesting how they bond as they write, becoming more than mother and daughter.

Jeannine Atkins

October 20, 2012

EarthView – WorldView

I gave a talk to students who are studying to become teachers at the University of Maine in Farmington at their annual Diversity Conference. At the same time, the New England Geographical Society was meeting on campus. And a part of that conference was a 20-foot inflatable balloon, hand-painted to look like a globe, and set up in the university gym. It happened that the talk I gave had the title, Center of the World. I’ve been fascinated by the Buddhist idea that wherever we are, anywhere in the world, we are in the center. Wherever we walk, everybody is walking in their own sacred space. Of course where I was going with that is that, through books, we can begin to imagine the world’s of others. I found this to be the most wonderful syncronicity that I could walk down the windblown, golden streets of Farmington to the gym and see this world, called EarthView, a creation of Bridgewater State University. This photograph is by Jacob Belcher and it appears in the Bridgewater Independent. He captures the vivid colors of the gorgeously painted earth and the silhouettes of students who have climbed inside Earthview. ”It’s a globalized world,” the newspaper quotes Bridgewater geography professor Vernon Domingo. Here was a grand way to experience it. Soon I’ll post my talk, Center of the World,

I gave a talk to students who are studying to become teachers at the University of Maine in Farmington at their annual Diversity Conference. At the same time, the New England Geographical Society was meeting on campus. And a part of that conference was a 20-foot inflatable balloon, hand-painted to look like a globe, and set up in the university gym. It happened that the talk I gave had the title, Center of the World. I’ve been fascinated by the Buddhist idea that wherever we are, anywhere in the world, we are in the center. Wherever we walk, everybody is walking in their own sacred space. Of course where I was going with that is that, through books, we can begin to imagine the world’s of others. I found this to be the most wonderful syncronicity that I could walk down the windblown, golden streets of Farmington to the gym and see this world, called EarthView, a creation of Bridgewater State University. This photograph is by Jacob Belcher and it appears in the Bridgewater Independent. He captures the vivid colors of the gorgeously painted earth and the silhouettes of students who have climbed inside Earthview. ”It’s a globalized world,” the newspaper quotes Bridgewater geography professor Vernon Domingo. Here was a grand way to experience it. Soon I’ll post my talk, Center of the World,

October 15, 2012

The Verse Novel: Caroline Starr Rose

“Braiding the Verse Novel” is a series of interviews I did with writers of novels – and one biography - in verse. We had our conversations over the summer of 2012. I’ve written articles about verse novels for School Library Journal and NH Writer  which draw on these conversations in different ways. Here, I’m posting the generous responses from each of the writers who allowed me to ask them questions.

which draw on these conversations in different ways. Here, I’m posting the generous responses from each of the writers who allowed me to ask them questions.

Caroline Starr Rose, author of the award-winning middle grade novel May B.,takes readers into a culture of poverty on the Kansas frontier of the 1800s. Here’s our conversation.

Terry: Would you select a few lines from your novel and tell about a choice you made in the craft of those lines?

Caroline: I adore this question, partly because I write by ear, if that makes sense. I know other verse novelists who use specific forms. Hearing them speak often makes me feel like a dunce. The wise Carolee Dean (FORGET ME NOT, Simon Pulse/Oct 2012) recently shared with me all the devices she found in my own work — things like alliteration, internal rhyme, assonance, she intentionally plans that I don’t really think about — and it was eye opening. It was a reminder that there is no one way to write. In drafting, rhythm, sound, and the visual play a huge role in how my story unfolds. Here is an example:

My legs fold under me

as I try

to catch

my breath

between sobs.

This stanza shows May’s full understanding she’s been abandoned. My editor wanted to make sure the reader was visually and emotionally present in this moment. I added all sorts of words that in the end just weren’t right. My editor suggested we keep the stark, simple language and change the line breaks so that the reader, along with May, must slow down and catch their breath — literally experience the emotion with her.

That’s the power of poetry: it communicates beyond just the words on the page. It is most fully understood, I think, when it is spoken, seen, and heard — when the senses are fully engaged.

Terry: Can you draw a parallel between your use of poems to create the novel and cultural or literary traditions of the community represented in the novel?

Caroline: May B. didn’t start as verse. What I first wrote very much frustrated me, as it felt so distant from what I’d imagined. I set my writing aside and returned to my research. In reading first-hand accounts of midwestern women in the late 1800s, I picked up on the similarities their journals and letters contained — terse language stripped of emotion and verbose description. I returned to my drafting, trying to mirror the style of these women. This was the key in discovering May’s voice and most honestly telling her story.

Terry: Do you thing that there is a kind of story that is best suited to the verse novel form?

Caroline: For me, verse works best when working with a very close first-person point of view. It allows access to a character’s thoughts without many extras. I also love the immediacy verse gives, not only to the character but the setting. Verse has become a great vehicle for me to write historical fiction because I want the character and her world to feel real, present, and accessible. Ideally, history comes alive when readers see how similar our feelings, fears, and motivations are when paralleled with people from a different era.

Terry, this is wonderful. Thank you for allowing me to participate. I love your angle on using poetry to convey culture and language. I think this is why books where children have limited language skills/new language acquisition work so well through verse. We experience the story through the characters’ eyes. —Caroline Starr Rose

October 4, 2012

Braiding the Verse Novel: Margarita Engle

“Braiding the Verse Novel” is a series of interviews I did with writers of novels – and one biography - in verse. We had our conversations over the summer of 2012. I’ve written articles about verse novels for School Library Journal and NH Writer which draw on these conversations in different ways. Here, I’m posting the full responses from each of the writers who allowed me to ask them questions.

Margarita Engle is the Cuban-American author of The Surrender Tree, recipient of the first Newbery Honor granted to a Latino writer. Her other young adult novels in verse include The Poet Slave of Cuba, Tropical Secrets, The Firefly Letters, Hurricane Dancers, and The Wild Book. The Lightning Dreamer is forthcoming from Harcourt in March, 2013. Engle has received two Pura Belpré Awards, two Pura Belpré Honors, three Américas Awards, an International Reading Association Award, and the Jane Addams Award. She lives in central California, where she enjoys helping her husband with his volunteer work for wilderness search and rescue dog training programs. Her next picture book is When You Wander, a Search and Rescue Dog Story, forthcoming from Holt in March, 2013.

Margarita Engle is the Cuban-American author of The Surrender Tree, recipient of the first Newbery Honor granted to a Latino writer. Her other young adult novels in verse include The Poet Slave of Cuba, Tropical Secrets, The Firefly Letters, Hurricane Dancers, and The Wild Book. The Lightning Dreamer is forthcoming from Harcourt in March, 2013. Engle has received two Pura Belpré Awards, two Pura Belpré Honors, three Américas Awards, an International Reading Association Award, and the Jane Addams Award. She lives in central California, where she enjoys helping her husband with his volunteer work for wilderness search and rescue dog training programs. Her next picture book is When You Wander, a Search and Rescue Dog Story, forthcoming from Holt in March, 2013.

Terry: Would you select a few lines from your novel and tell about a choice you made in the craft of those lines? How did you shape them to achieve something key to the story? (This is a wide open question. Maybe you used or created a formal structure and would describe that. Maybe rhythm was key to you. I look forward to hearing wherever this question takes you.)

Margarita: Writing a historical novel in verse is a process of exploration. In the opening poem of The Surrender Tree, I imagined what it would feel like to be a young, enslaved, self-taught wilderness nurse, whose gift of healing is misunderstood as something dangerous and malevolent. In the voice of Rosa la Bayamesa, I explored her point of view:

Some people call me a child-witch,

but I’m just a girl who likes to watch

the hands of the women

as they gather wild herbs and flowers

to heal the sick.

I am learning the names of the cures

and how much to use,

and which part of the plant,

petal or stem, root, leaf, pollen, nectar.

Sometimes I feel like a bee making honey—

a bee, feared by all, even though the wild bees

of these mountains in Cuba

are stingless, harmless, the source

of nothing but sweet, golden food.

I imagine only a Cuban would notice that the part of this poem that refers to the names of cures is an echo of one of José Martí’s Versos Sencillos (Simple Verses) about finding comfort in knowing the names of wildflowers. However, I believe that everything else in this poem is universal. All young people experience times when they feel misunderstood. Nature, healing, and hope are also aspects of life shared by all cultures, and all ages. Rosa la Bayamesa healed soldiers from both sides during thirty years of warfare, so I knew I had to carry her character into adulthood. I also knew that later in the book, there would be a scene with children saving her hideout by placing beehives in the path of enemy soldiers. It was an incident I had read about, one too important to omit, but I can’t say that I consciously used the bees in this first poem to foreshadow the later scene. I spent so much time immersing myself in the research that real events floated around in my head, searching for places to land. Throughout the imaginary thoughts in this novel, documented historical events wove themselves into the poems.

Terry: Can you draw a parallel between your use of poems to create the novel and cultural or literary traditions of the community represented in the novel?

Margarita: Poetry and music play such an essential role in Cuban culture that it was natural to include them. Since the book was really about people like Rosa, who did not leave a diary or any written record of her life, I made only brief references to the most beloved poet of those times. José Martí is the “father” of Cuba’s independence from Spain, but his martyrdom in the “Spanish-American War” is so well-known that I only mentioned his poetry in passing. Instead, in a series of poems beginning on page 106, I let the voice of a young refugee girl named Silvia speak about natural sounds, along with the birdcalls of Mambí rebels, who communicated while in hiding, using the Canary Island tradition of a language of whistles:

Mambí birdcalls, a stream, tall reeds, the song

of a waterfall, my own tumbling, exhausted,

singing wild hopes.

Next, on page 107, the voice of Rosa’s husband, José, speaks about music:

All night I stand guard, singing silently

inside my mind, to keep myself awake.

Then, on page 108, Silvia marvels at the power of song:

Does the old man in the forest

know that he sings in his sleep?

And finally, on page 109, Rosa turns to non-verbal communication with young Silvia:

I see a story in her eyes.

She thinks she has no right to eat

while so many others starve.

If I had to describe the rhythm of these poems, I would say there is a hoofbeat. Like so many of Cuba’s improvisational “country music,” songs from this era were sung on horseback. I picture an easy lope, the kind of pace that a horseman would use to cover great distances without tiring his faithful mount.

Terry: Would you suggest that there is a kind of story that is best suited to the verse novel form? Tell me your thoughts.

Margarita: I would like to think that any sort of story could be told in the novel in verse form, but that might only be true of the kinds of stories that interest me. I don’t enjoy the distance of an omniscient third person narrator. I love to plunge straight into the heart of the story’s events and emotions, using thoughts and feelings rather than long descriptions and dialogue. At the same time, I do enjoy the visual aspects of a story, so I use what I know about nature and the five senses. The Surrender Tree is set in tropical rain forests and caves. Sounds, sights, fragrance, stench, all of it has to be included, so that both the author and reader can time travel back to a remote Cuban jungle where former masters and former slaves fought side by side, for the shared goal of independence from Spain, followed by peace, the greatest treasure.

September 15, 2012

Folktale Festival Picture Show

Hari Tiwari and Terry photo by Deb Cram

Here’s a photo gallery from our Folktale Festival celebrating The Story of a Pumpkin by Hari Tiwari. She told the story in her ELL class in Laconia, New Hampshire. It was a story her father told to her when she was a little girl. And now the New Hampshire Humanities Council has published the tale in Nepali and English with the help of the Bhutanese Community of New Hampshire, folklorist Jo Rader, book artist, Susan Kapuscinski Gaylord and many ELL teachers. The University Press of New England is distributing the book. Photos in the gallery are by the extraordinary Deb Cram for the NH Humanities Council.

September 1, 2012

Fight Like a Girl

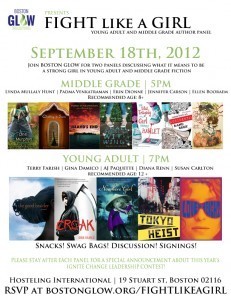

Boston Glow, a girl’s leadership organization, is sponsoring a panel of young adult writers. The topic is: What it means to be a strong girl and how the characters in our novels portray that strength. I am very happy they invited me to talk about Viola and her stamina. For details on the event you can visit Boston Glow.

Boston Glow, a girl’s leadership organization, is sponsoring a panel of young adult writers. The topic is: What it means to be a strong girl and how the characters in our novels portray that strength. I am very happy they invited me to talk about Viola and her stamina. For details on the event you can visit Boston Glow.

July 22, 2012

Braiding the Verse Novel: Carol Fisher Saller

“Braiding the Verse Novel” is a series of interviews I did with writers of novels – and one biography - in verse. We had our conversations over the summer of 2012. I’ve written articles about verse novels for School Library Journal and NH Writer which draw on these conversations in different ways. Here, I’m posting the full responses from each of the writers who allowed me to ask them questions. Nearly everyone who has read my novel, The Good Braider, asked me why I wrote in the spare lines of verse. My readers’ questions have caused me to explore my own craft and then to explore the question with these articulate, generous writers. Each week I will feature a new novelist.

is a novel in poems. Each of Carol’s poems could stand alone as a character portrait or vignette. ”A poignant look at boyhood before and during the long years of World War II,” writes Kirkus in a starred review.

1. Would you select a few lines from a verse and tell about a choice you made in the craft of those lines? How did you shape them to achieve something essential to the story?

There were two difficult choices I had to make in writing Eddie’s War: first, whether to write in straight prose paragraphs or in the more stark, short lines that were calling to me, and second, whether to write in first or third person. More than one reader told me I’d be better off with third-person paragraphs. But compare these two versions of the same passage:

(Before)

One summer when Eddie was helping Thomas cut thistles in the bottoms, they heard snuffles and whines and followed the sounds. On his knees, Thomas dug into the side of the hill, into the den, and handed them out, one by one, little foxes, small and soft and wriggling. The boys used their shirttails to hold the kits, four in all.

(After)

When the Hindenburg caught fire

and fell out of the sky,

I saw the pictures

in the paper.

“I seen ’em, Tom,” I was saying,

out south cutting thistles,

“people jumping out

an’ it still up in the air”—

But Thomas looked up,

said hush.

There was whining

somewhere in the grass.

We followed the sounds.

On his knees Thomas dug with his hands

into the hill

into the den,

handed them out one by one,

little foxes.

To me, the first passage just plops along: This. Then. That. The second passage puts us right there with Eddie, looks through his eyes, gives him a voice, a personality, then makes us wait along with him—the short lines delay and build—to see what will come out of the hill. We wait for Thomas to turn and hand us . . . what? I finally thought, what the heck, who cares if this sells, and I wrote it the way I wanted to.

2. Can you draw a parallel between your use of verses and style of verses to create the novel and cultural traditions of the community you write about. The term cultural could refer to the time period, to war, to a family, or other culture.

I hope that some of my vignettes evoke the sound and rhythm of country speech and another era. The short lines slow everything down and allow for the kind of terseness or shyness that several of my characters have. I suppose my form (I don’t think of it as verse) is imitative in some ways: I have a powerful admiration for Karen Hesse’s work, Out of the Dust, for instance.

3. Would you suggest that there is a kind of story that is best suited to the verse novel form?

I think the form lends itself to any kind of story, but not to just any kind of storytelling. It’s for when the teller wants to tread carefully, choose each word, edit, hone, listen for clinkers, and push until it’s right. But I don’t see why it couldn’t work just as well for distopian fantasy or urban grit or even middle-grade humor. In another project I’m working on, my main character is a modern-day girl who is impulsive and brash, and it never even occurred to me to write in short lines, because that’s not the way I want to tell her story.

4. What’s an ingredient in a verse novel that makes you fall in love with it?

For me it’s pacing within and among the sentences, the way they ebb and flow. I think each person finds certain rhythms and sounds and pacing to be especially pleasing, and when I read a novel whose narrative style clicks with me, it’s like that writer is singing my song. I had that experience reading In an Uncharted Country, by Clifford Garstang. Maybe because Cliff and I both lived in central Illinois for years as kids (he’s a friend from high school), we share an ear. His book isn’t a novel in verse, but it could be, it’s that lyrical.

June 25, 2012

The Way We Write

Pugs, Merengue, Dolce & Gabbana

By Terry Farish

In a first draft, the one that makes me cry over some truth I’ve finally seen, for a flashing moment, I am sun god.

I am sloppy and haphazard in my journal keeping, but my journals are invaluable to me when I go to write that first draft. I have no idea how I will use a line. All I know is that when I gather details in my journal, I am writing from my best self, the self who is trolling the world, slightly amused, curious, often awed.

I know a woman whose speech I love. She speaks in animal metaphors—“I’m gonna buffalo through the job” and “I’m gonna ferret through my stuff.” My best self wants to write down all those wonderful animals she makes into verbs. I’m not responding to her from my ego—I’m beyond ego—I’m capturing a truth of how a person thinks. Power struggles and hurt feelings pale compared to anticipating her possible uses of pug.

My muse—you’re going to have to forgive this cliché—my muse comes out of giving in to love. I worked in a library with a woman who has just learned how to do story programs. She grabs dads by the arm and gets them to stand up and dance the merengue after we read My Feet Are Laughing, about a little girl who dances merengue with her mother in Harlem. Then the new storyteller takes a baby and whisks her away. The first born child of two bedazzled parents is up there dancing merenge in her arms. And I fall in love with this woman’s style and I have to write about her.

In my journal voice, I wrote down an old man’s stories during the years he was my neighbor in an English village. He told me the story of an old buddy and his cat, how the cat was getting on, and the old man needed to put the cat out of her misery. I wrote in my journal, “The man cried all the way to the river and he cried all the back.” I felt such affection for my neighbor and I wrote The Cat Who Liked Potato Soup for him.

In an essay by Julius Lester he told about his father dying and he was bereft because he loved his father. He posed the question, what am I going to do with all this love? He said he would use it to write. And I understood that. He turned all that emotion into his muse, his energy to create.

There’s plenty else to give in to in this world, to be enraged by, to abhor. I am writing about Sudan, not because of my hatred of the genocidal civil war, but because I met a young refugee from Sudan who took my breath away with her courage and my journal became full of her voice.

Recently I wrote about my stepdaughter, who was graduating from high school. She and I have had an awkward, silent relationship.

“You’ve cut your hair,” I wrote one day, “so you have jagged black locks across your cheek and forehead—a mod European look like pictures of models on your bedroom wall that say Dolce & Gabbana and you have a kind of duffle bag slung over your shoulder and you look like you’re leaving for Rome and I want to say, no, wait, you have to stay.”

When I find my best self, loving her, that’s when I can write.

Reprinted from the Newsletter of the New Hampshire Writer’s Project