Waubgeshig Rice's Blog, page 2

June 17, 2018

Keeping the circle strong

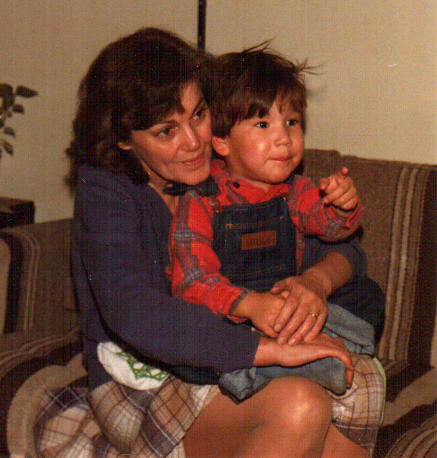

Me and my dad c. 1980

It’s by and large a Hallmark holiday, but I do like to proclaim my love and thanks for my dad on Father’s Day, even though I’m grateful for him every day of the year. He’s always fulfilled the criteria of a good dad according to the sentimental cards and pop culture. He taught me how to shoot a puck, always kept the fire going, and took all the driving shifts on those long family trips. But he went above and beyond those stereotypical traits to try to raise his children the best he could even though he had no template to follow.

He came to the drum when I was a little boy, so I was very fortunate to grow up drumming and singing our Anishinaabe songs. It was a crucial part of a long and medicinal journey that brought him to ceremony and a deeper understanding of his culture and background. My mother, brothers and I benefited greatly from his reconnection with the Anishinaabe way of life. He sought the drum and our old ways for healing, and it helped us all thrive.

His own father died when he was just 29 years old. He fell off a boat on a cold fall morning just off the shore of our reserve and never came back up. He left behind a wife and five children all under the age of seven. My dad was just five years old. He has little memory of my grandfather, and wasn’t able to share much about him throughout my upbringing. But it was always clear to me that he grew up without a dad, and from a young age I imagined it must have been tough for him to learn how to be a father without having his own.

There were challenges, of course, but he still did a wonderful job raising us. And that’s become much more evident now that I have a son of my own. Parenthood is the ultimate test of a person, and although my journey is really just beginning, I have a much greater appreciation of my parents and the sacrifices they made for us to ensure we grew up in a good way. My dad really did have to figure out fatherhood on his own, and my mom supported him and us along that path.

It was pretty neat to see him reflect on that experience in this video with other Indigenous men that came out a few years ago:

PERFORMANCE – First Nation Dad Roles from Brian Russell on Vimeo.

Although ultimately heartfelt and hopeful, these candid reflections illustrate the widespread, tragic challenges of Indigenous fatherhood on Turtle Island. Colonialism, forced assimilation, and ongoing oppression have severely damaged traditional parenting practices and ideals. Violence like residential schools and the enforcement of the Indian Act infected Anishinaabe masculinity with a brutal toxicity that lingers and continues to manifest itself in horrible ways.

As a result, Indigenous fathers are expected to neglect or destroy. And that happens. But it’s important to remember what’s at the root of that behaviour and why many of these men are struggling. Otherwise stereotypes of the violent or absent Native dad will persist and even become a self-fulfilling prophecy for many young men who become fathers. It’s ultimately up to them to break those cycles, but they need a supportive and understanding community to empower and enable them.

Being a father is the greatest joy I have ever known. My son is the greatest gift I have ever received. I love every moment with him; from teaching him to talk to tempering his tantrums. I walk proudly with him, whether it’s pushing his stroller or taking his hand in mine. Making it just a year and a half into this journey feels like my greatest accomplishment. He teaches me something new every day, and I can’t wait to keep walking on the rest of this path with him.

My responsibility as a father is to raise him to be kind and respectful. It’s on me to ensure that he grows up as a loving and humble person who treats everyone around him as he’d want to be treated. I want him to be patient and polite, and to try to be positive whenever he can. I hope he follows his dreams and never denies his feelings. These are some of the basic values that guide parents in all cultures and nations in raising decent human beings.

These are ideals that were embedded deeply in me thanks to my parents, my family, and my community, despite the intergenerational trauma of displacement and assimilation. Violent cycles were broken, but more importantly, a strong circle was maintained. Strong Indigenous parenthood is about creating and sustaining viable communities, and at the core, survival.

Me and my son Jiikwis, 2018

March 18, 2018

Baamaapii Nookomis

Another powerful and revered matriarch has left this world. My dear grandmother Aileen Rice died last month, a week shy of her 87th birthday. I have struggled since her death to put into words just how monumental and important she was to her family, her community, and countless others who she touched in some way. She was a passionate advocate for Anishinaabeg everywhere, lobbying for language and tradition in spaces where authorities tried to erase culture. She fought for equal access to education for Indigenous children. She was a woman of strong faith who incorporated Anishinaabe beliefs into Christian teachings as a minister. She embodied resilience and spirit by enduring some of life’s most brutal hardships and rising up to empower everyone around her.

It’s impossible to capture in mere paragraphs the widespread impact of my grandma’s legendary life and esteemed legacy. I want to write something much more comprehensive about her renowned accomplishments and family story sometime in the future. Losing her less than a year after my grannie died has been very hard, but reflecting fondly on the amazing lives of my grandmothers has been a silver lining to the often dark clouds of the grieving process. So I’ll share just a little bit now, because I want to acknowledge and honour her in every way I can.

My grandma was affectionately known as “Auntie Soda” to generations of people from Wasauksing, Parry Sound, and well beyond. She was born on the land and was proud to live the Anishinaabe way. One of 11 children altogether, she spoke only Anishinaabemowin throughout her childhood and carried her people’s stories and teachings from an early age. She would later regale us, her grandchildren, with these treasured details of our heritage and the generations of family lines that we could draw deep into Anishinaabe territory. It was an honour to learn these stories from her.

There’s so much about her vibrant life to take pride in, especially being a part of the strong family she led. She and my grandfather married young and had five children by their late 20s. When he died in a tragic boating mishap, she was left to raise them all on her own. The oldest was seven years old and the youngest was two months. The threat of apprehension loomed constantly. Her kids – including my father – could have been taken to residential school or placed in the child welfare system. Breaking up Indigenous families and erasing culture was official Canadian policy. But somehow, she was able to resist that at every turn, and kept them all together at home.

When that threat dissipated, she took her place as an ardent advocate for equal education opportunities for Indigenous children. She became the first Anishinaabe person to serve on the nearby town’s school board. She then adopted two more children from a relative, bringing the total to seven she raised by herself. All of her kids went on to post-secondary education beginning in the 1970s, when Indigenous people were rarely considered for or seen in universities and colleges in Canada. My grandma blazed a trail that made it much less difficult for me and my cousins and peers in Wasauksing to follow.

These are just a few basic and brief highlights. There’s so much more she lived through, like losing a daughter to homicide and never seeing justice for her. She lost many more relatives to tragedy. She saw her beloved Ojibwe language gradually fade from our community. She endured her homeland in the depths of despair and abuse, but she never gave up hope that it could one day heal. All the while, she never let any of her losses or hardships define her, and she never took any shit from anyone.

My grandma is gone now, but her story is still being written. Her spirit continues to thrive in all of us who are proud to be Anishinaabe. And I’ll share more of her remarkable journey as soon as I can. Baamaapii Nookomis. Gizaagin.

December 12, 2017

Weweni sago

Weweni sago. It’s a phrase in Anishinaabemowin that can mean “take care.”

A few weeks before his first birthday, I bounced my son in my arms, trying hard to savour the moment while chasing harsh memories from my mind. A family celebration was looming and that should have been my focus, but I couldn’t stop thinking about how he and his mother almost died the day he was born.

They both fully recovered and now thrive in the most beautiful ways. But for some reason, I kept replaying that traumatic moment and those precarious first days. I didn’t know why I thought that way and it really troubled me. I cradled him close with determined care in my arms and immense love in my heart, while fear and anxiety lingered in my head.

There was no reason to be afraid or anxious. We were blessed with happiness and health as a new family. And while his birth was physically devastating for both him and his mother, I felt like it was “only” emotionally traumatic for me, and that I should have gotten over it by then. Their strength and resilience inspired me every day. Why couldn’t I embrace the wonder, beauty and power of this life and stop the trembling in my fingers?

This internal tension peaked when I couldn’t really bring myself to speak during those bizarre new episodes. I found myself unable to express exactly what I was feeling, which was something I had never experienced. My wife Sarah – ever kind, supportive and loving – noticed, and we tried to talk some of it out.

Together we identified a persistent grief from those moments in the hospital that I had never really addressed. I kept thinking about what my life would be like without them, even though they were tangible, real, beacons of love and might right in front of me. All this time later with no real reason to worry, I knew those were irrational thoughts.

Then she reminded me about what else happened in the last year. My grandmother – one of my life’s pillars – had died in the spring. So did my uncle, the man who made me a rock n’ roll fan. There was great loss in her family too. Her great-grandmother and family matriarch also died in the spring. It was a heavy year of loss. And another person very close to me also experienced serious trauma, but I won’t explain out of respect for their privacy.

While those tragedies had compounded in a short time, I realized there were even more in my past that I still hadn’t emotionally resolved. A few years ago, two cousins of mine died in the same week – one of an overdose, and the other of suicide.

My aunt, who was a storytelling and traditional mentor to me, died suddenly a year before that. There were many more deaths and victims of violence close to me. A lot of my serious grief goes back to the loss of one of my best friends in a car accident when I was 16.

I hadn’t even considered how that grief could accumulate, like stubborn black soot in a stovepipe. Up until then, I thought I had grieved enough at each funeral. The ceremonies around death in our culture make time and space for this very important process.

A fire burns for four days of mourning to make way for a relieving celebration at the end when the spirit leaves this realm to find their way to the spirit world. It’s a beautiful practice that helps the family and community heal from the loss. But when so many of them happen in a relatively short time, maybe it’s harder to fully expunge that sadness.

It’s no secret now that tragedies strike First Nations much more frequently than other communities. A long list of human calamities plague reserves: disease, suicide, violence, abuse, and so on. These are well documented, and the immense weight of these ongoing losses is devastating. A friend recently wrote that being Indigenous in Canada is to be in a perpetual state of grief.

And with all kinds of media constantly feeding reminders of these disproportionate tragedies to First Nations, it’s almost like they become a self-fulfilling prophecy of doom. It’s easy to convince yourself that grief and suffering are ingrained in Indigenous identity, and that sadness is permanently fused to our DNA.

All these troublesome thoughts and feelings swamped my mind as soon as it idled. It felt like gravity quadrupled as soon as my focus shifted from my family, my job, or other activities that kept me occupied. Grief was dragging me down, and although it hadn’t taken a major toll on my professional life or my home life yet, it was only a matter of time before it became truly burdensome and I wouldn’t be able to function or focus on work or the happiness that flourished in my home.

Thankfully, my wife saw this become more serious as I became a little withdrawn. My silent sorrow hinted at inner emotional turmoil she’d never seen in me up to that point. She suggested I seek out and speak with a grief counsellor. She helped me find one here in Sudbury who was Anishinaabe and could help me look at my situation through a cultural lens and get me back on a positive path.

I was open and willing to receive this help. Throughout my life, I’ve always considered myself the one others go to when they’re grieving or down. I’ve always believed that I’m emotionally and spiritually strong. I grew up going to ceremonies, which built a strong cultural foundation that created a powerful link to my family, community, and Anishinaabe identity.

But I wasn’t strong enough to handle this on my own, and I was too apprehensive to discuss it with family and friends. I didn’t believe my personal issues were as serious as what other people were living through. I needed an outside perspective to ground me once again.

So I went to the Shkagamik-Kwe Health Centre for help. Without going into the details of the discussion, the person I sat with was able to bring me back to centre. She helped lift a massive weight off me. I understood what had happened to me. And I realized that unresolved grief can have serious consequences. I’m very thankful for this person’s guidance, and to my life partner for leading me to her.

I’ve never suffered seriously from anxiety, depression, or any other mental illness, although I do my best to advocate for people who do. Through this all, I’ve learned that grief isn’t fleeting. It doesn’t disappear when the fire goes out at the end of a funeral ceremony. Sometimes it tucks itself away, hiding behind those fulfilling moments of relief and celebration when family and friends come together in death. It’s an infectious mould that propagates as the years go on and the death toll rises. It has to be acknowledged and confronted, or it never goes away.

I share this for the sake of transparency and to encourage discussion. As a journalist, I write regularly about the grief and loss of others. As an author, I often adorn my own emotional hardships with the mask of fiction. But I believe it’s important for someone like me to be candid about these very real difficulties. It’s helping me, and hopefully writing this will support others in getting help as well.

Weweni sago.

November 5, 2017

“You may not be my last, but you’ll always be my first”

I have personal soundtracks for different phases of my life, and my new journey into fatherhood is no different. Our son Jiikwis is almost a year old now, and a few recent standout songs have really punctuated my time with him so far. He’s also inspired me to revisit some of my old favourites, which either hit closer to home or have taken on a whole new meaning. Being a parent really is the most profound experience I’ve ever had, and when I can’t put into words just how much it means to me, there’s usually a song that perfectly encapsulates what I’m feeling.

Below is a small handful of the songs about fatherhood (or that I interpret as such) that I’ve recently enjoyed. But I couldn’t find a decent link to my all-time favourite tune about the arrival of a child: Sturgill Simpson’s “Welcome to Earth (Pollywog)” from his outstanding 2016 album A Sailor’s Guide to Earth. At the moment, everything on YouTube seems to be bootleg video from concerts. If you don’t know it, I highly recommend getting the album, and in the meantime you can read about what it means to me in this post from shortly after our son was born:

A post shared by Waubgeshig Rice (@waub) on Dec 10, 2016 at 2:26pm PST

What are your favourite songs about being a parent?

July 2, 2017

A grandmother’s everlasting embrace

My very beloved grandmother Ruth Shipman died on June 9, 2017. She embodied everything wonderful about the richness of life, and nearly a month later, it’s still hard to believe and accept that she’s gone. But she lived a very impressive and inspiring 92 years, and I’m extremely proud to be part of her legacy as her grandson. I look back on my life with her with great fondness, adoration, and love.

She was a constant presence throughout my childhood, teaching me to be kind, patient, and creative as she helped raise me. Our time together back then was always filled with all kinds of fun activities. She always encouraged me and my brothers and cousins to engage in pretty much anything that enriched our lives. She was a very passionate storyteller, and often made up vivid stories on the spot to entertain us. She inspired me to let my imagination take me anywhere, and I credit her with leading me to the journey that I’m on today.

I was motivated to succeed in school and in my professional life just to tell her about my accomplishments. I took so much pride in the faith and belief she had in me. She held me up in so many ways, and I became a confident and passionate person because of her influence. She was a huge CBC fan, and being able to tell her that I was hired by CBC to be a reporter was one of the proudest and best moments of my life.

She was a nurse who was committed to healthy living. She was hospitalized for years when she was young because of tuberculosis, and she survived that to emerge as a true force for living in a good way. I really thought she was invincible, which is what makes her death pretty hard to accept. But I can honour her by making sure I live as long as possible as well.

It’s pretty mind-boggling to know that a person who is one quarter of who I am is physically gone. But I feel her with me and in me, and I know that she will always be there. And I see her in my son, and I take great comfort and pride in knowing that he will carry her with him throughout his life as well. I’m very grateful that they were able to share moments in this world together. I can’t wait to tell him all about her.

I love you, Grannie. Rest well.

March 5, 2017

“You had a plan for us”

Sarah and Jiikwis in the special care nursery.

Our son Jiikwis is now three months old! He arrived in early December, four weeks early, after his mother suddenly became eclamptic one morning. It was a frightening medical crisis, but thanks to the quick thinking of our midwife and doctors and nurses at the Ottawa Civic Hospital, an emergency c-section saved both of their lives. It was a very traumatic event, but they both fully recovered, and after six days in the hospital, we were all able to go home. Those first days were the scariest and most stressful of my life. But as the trauma has subsided, the memories of that time have also started to fade. Sarah and I wanted to make sure Jiikwis knew everything about his birth, so we recorded a conversation we had with him to explain the details. I decided to transcribe some of that and post it here, for the sake of documenting this important time in our lives, and to share our story with other parents who may be experiencing something similar. I’ve edited the transcript for length and clarity.

Waub: Jiikwis, we first found in the spring that your mama was pregnant, and we had a summer of excitement.

Sarah: We were planning on giving birth at the Ottawa Birth and Wellness Centre. And we had a midwife all set up – Jessica. We saw her a bunch of times, and we made the decision that we were going to have a natural birth. There was always going to be the option of going to the hospital if we needed to. We had it all planned out. We even went to prenatal classes. We did hypnobirthing classes. So your mama was gonna do it all. And we were very excited about bringing you into the world in a very quiet and calm and beautiful way.

W: As time went on I had my own vision and wishes as to how it was going to happen. We were going to play some relaxing music. I was going to sing you in on the hand drum. I wanted to say some things in Anishinaabemowin. Because I thought it would be really cool if the first sounds you heard in your life were the drum and your native language. That’s what we were hoping would happen, but it didn’t really work out that way.

S: The night before you were born, your mama wasn’t really feeling good. I had a really bad headache that night, and I couldn’t sleep. I had pain in my ribs, and it felt like I had really bad gas. And then I started getting pain in my diaphragm as well. I ended up pacing around the house all night, and I didn’t get any sleep. I vomited twice early in the morning. So at 6AM I emailed my boss and said I wouldn’t be in to work that day. I already had an appointment with the midwife scheduled, and I told my boss that I was going to go see her to see what was up. I told your dehdeh (daddy) to go ahead to work, and that I’d be able to drive myself to the appointment on my own.

I got to the appointment and I really wasn’t feeling well. Waiting to go in and see the midwife felt like torture. I finally got into her office and I was describing to her how I felt, and she was very concerned. And then all of a sudden my head started turning. I was trying to look at her, but my head kept pulling back in the other direction, and it was really shaking. And that’s the last thing I remember.

W: I went to work and your mama and I were texting back and forth. She was keeping me posted on how she was feeling. She still wasn’t feeling great, but the fact that she was in touch with me was putting me at ease, because I knew she must have been okay. And then I had an interview to do at work. I was at a hotel downtown to do a story about a conference. That interview took about ten minutes, so after it was done I checked my personal phone, and saw that there was a missed call and a message. I checked the message and it was the midwife’s office. They said “Waub, Sarah has collapsed. She’s gone in an ambulance to the hospital. You should go there right away.” So I called back to confirm that’s what was going on, and they said yes, she’s at the Civic Hospital. Go there right away. So I ran back to the newsroom to get my stuff, and went back outside to get a cab to the hospital.

I went right to the emergency room, and asked for your mama, but the woman at the desk looked at the computer and couldn’t find a Sarah Rice. She said sometimes it takes a little while for patients to show up in the system, because they’re most likely being cared for by ER staff. So I said okay, I’ll wait. And at that point I wasn’t really that worried, because I knew she was with her midwife, and they got her to the hospital as quickly as possible. I figured she was maybe dehydrated, or maybe feeling weak or sick, which made her collapse. So I decided just to wait some more.

But the longer I waited there, the more worried I got. There were no updates, and they still couldn’t find her. I thought, well maybe she’s actually in labour, and I thought that maybe you’d be coming later that day. That made me pretty nervous. About 20 minutes passed since I got to the ER at the Civic, and they still couldn’t find your mama for me. I started to get really irritated. Then, out of the blue, the midwife’s office called me again. They said “Where are you? Are you at the hospital yet?” And I said “Yeah, I’ve been waiting in the ER but no one can tell me where she is!” Then they said “You need to get up to the labour and delivery unit on the 4th floor. That’s where Sarah and your baby are.” And when they said that, I felt like I left my body. It straight up stunned me. Because that’s when I first learned that you were in this world, Jiikwis. It totally blew me away.

One of the ladies at the ER desk told me how to get up there. My mind was racing and tumbling as I walked through the halls. When I got up there, there was a whole team of doctors and nurses waiting for me. They basically explained to me everything that happened. They said your mama had a seizure at the midwife’s office because she had really high blood pressure. The paramedics came and got her, and she regained consciousness. They took her to the hospital, and Jessica the midwife rode along. But when they got your mama into a bed in the hospital, she had another seizure. So they checked on you, and found your heart rate was dropping dramatically.

S: And this was when you were still in mama’s belly.

W: Yep. So they said we have to get the baby – you – out as soon as we can. They made the decision to do an emergency c-section right away.

S: I don’t remember any of that. I don’t remember being at the hospital that day. I don’t remember anything. My last memory was at the midwife’s.

W: The doctors told me what happened. It was a pregnancy condition called eclampsia, that basically means sudden high blood pressure that causes seizures. Obviously I was shocked, because the pregnancy was problem-free up until then. They said you were both in critical condition at first, but were now in stable condition. Then they said “do you want to see your baby?”

They led me down the hall and into a little room. The first person I saw was Jessica, who looked very exhausted. But she smiled and said, “Waub, you have a baby boy!” And I looked to my right, and there you were, on a table with nurses all around you. You were moving around, your eyes were open, and that put me at ease right away. You were so beautiful. I was so thrilled, but also still really scared. But there you were! And I knew that you were gonna be okay. I could just tell.

They put you in an incubator and hooked you up to a ventilator and other machines, and they let me walk with you down the hall to the special care nursery, where they said you were going to be for a few days. We hung out there for a little while, then a nurse took me back to the room that your mama was originally in when she had the second seizure. And they told me I would have to wait there for a while, because mama was still unconscious from the operation. They told me they transferred her to the intensive care unit, but it would be a couple of hours before I could see her. I had some time to kill, so I started calling all your grandparents and aunties and uncles to tell them you were here. I still didn’t realize how serious the situation was, though.

The mid-afternoon came, and that’s when they let me go down and see your mama. And it was pretty scary. She was laying in a bed, hooked up to all kinds of machines, and she had a big tube in her mouth. The doctors and nurses there said “she’s gonna wake up soon, and right when she does, you have to let her know that the baby is here, and he’s okay, because she’s going to be able to tell that the baby’s not in her belly any more.”

So I sat beside her, and held her hand, and I saw your mama stirring, and her eyes start to open. I leaned over, and I said “Sarah, our son’s here.” And your mama knew right away. She understood. And that made that part a lot easier. Those were our first moments in this world of being a family. We were all apart, but we both knew you were here. I showed mama the pictures I took of you when I first saw you.

S: I don’t remember that, unfortunately. My first memories were the nurses taking the catheter out, and giving me a sponge bath!

W: There was another scare, where your mama’s blood pressure went back up. So the doctors kicked me out of the room to see what was up. I couldn’t see in, and got really worried. But it stabilized after a few minutes and I got to go back in.

S: During the seizures I bit my tongue really bad. And my tongue ended up black and swollen. It wasn’t very nice. I couldn’t feel anything or taste anything, or even talk very well. They brought me food, but I couldn’t eat any of it. I also had a big scrape on my forehead, because when I had that first seizure I fell face first on the floor in the midwife’s office.

W: So that night I called all the relatives again and told them the whole story, and I think it was a shock for all of them. Because when I first called that afternoon, I didn’t know all the details. I didn’t know it was a critical situation. I think it was hard for everyone to hear, but they were glad that everything was fine, and you both looked like you’d recover. So I spent that first night and all the next day walking between you in the special care nursery, and your mama in the ICU, which were on different floors at opposite ends of the hospital.

S: Mama knew that you were a boy right from the very beginning. As soon as I started feeling inclinations of what kind of baby you might be, I always maintained that you were gonna be a boy. I don’t know why. Mama’s intuition, I suppose.

W: The next afternoon at 4 mama was finally able to leave the ICU. We wheeled her bed up to your floor, and as soon as she was ready, we put her in a wheelchair and took her down the hall to see you. It was a pretty special moment. I cried and cried and cried. When mama got to hold you for the first time, that was really special. Because that’s all I wanted to see that whole time. I kept thinking, as long as they can get together, everything’s gonna be okay. Everything got better. We had to wait for the breathing machine to come off. Then we had to wait for the IV to come out of your head. Then we had to make sure you were eating enough. But every day there was something new. Always something to look forward to.

S: The IV was very hard to look at, because it was right in the top of your head. And all that time, mama was trying to get her breast milk to come in. I was seeing a lactation consultant. Day 4 you were released from the special care nursery, and they brought your bassinet into mama’s room, and that was really special. And dehdeh and I – we started taking care of you ourselves. Feeding you, and changing your diaper. I never thought I’d be so happy to change a diaper!

W: Then on Day 6 we got to take you home. Everything looked different that day. It really felt like life had changed. The sun was shining in a new way. The snow on the ground looked brighter. You had a plan for us, which is why you came early, I think.

S: I was so relieved. We were going home with a new baby we hadn’t been totally prepared for, because you were four weeks early. But we were a family, and we’d already overcome some serious challenges already. We’re home now, and we haven’t looked back. And we’re getting stronger every day. We love you so much.

Photo by Shilo Adamson

January 11, 2017

Top Ten Albums of 2016

I’m a little late with the list for 2016, but I’m happy to once again post this annual exercise.

Sturgill Simpson – A Sailor’s Guide to Earth

The music is an interesting take on modern country music, and the lyrical concept is a love letter to his infant son. This came out the week I found out I was going to be a father for the first time. It became the soundtrack to that journey, up until my son was born in December. I will love this album for the rest of my life.

Iggy Pop – Post Pop Depression

He says his recording career is wrapping up, and I believe this is the perfect way to go out. He recruited Josh Homme – another of my all-time favourite musicians – to make this album, and the result is a rock n’ roll tour de force. Iggy at 69 is both raw and refined.

Tanya Tagaq – Retribution

When music defies all labels and the artist herself powerfully commands respect and space for her people in all realms, that’s revolutionary. Her last collection of songs took me places I never imagined music could, and this one took me even further.

A Tribe Called Red – We Are the Halluci Nation

They’ve gone from providing the soundtrack to the urban Indigenous experience to creating a global Indigenous movement that celebrates beauty, creativity, and positivity. The songs are a fun and exciting musical blend of electronic, powwow, and hip hop that follows a pretty compelling narrative.

Meshuggah – The Violent Sleep of Reason

No other band makes heavy metal as precise and powerful as Meshuggah does. These Swedish juggernauts have an unmistakable sound that’s complex and captivating, and decades into their dominant run, they’re stronger than ever.

Danny Brown – Atrocity Exhibition

I’ve always appreciated how dark and weird Danny Brown can make hip hop, and this one goes deep on both fronts. His skillful eccentrics yield some pretty serious bangers, while going to some harsh and profound places in between.

Big Business – Command Your Weather

Going back to their roots as a two-piece has somehow created louder, stronger songs than on their last (also excellent) album. Some may consider it a stretch to call Big Business “metal”, but I think they’ve created some of the most unique and enjoyable music in the genre.

The Melvins – Basses Loaded

Their production pace is roughly an album a year, and while recent output has ranged from just okay to deadly, Basses Loaded lands on the deadlier end of that spectrum. It may seem like a gimmick, but using a different bass player for each song results in a pretty eclectic heavy sound.

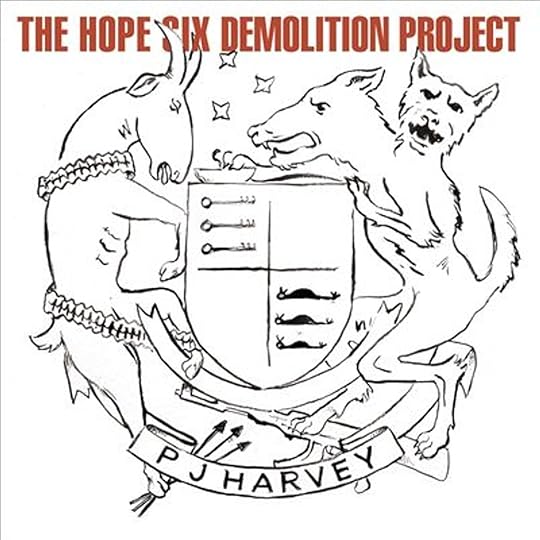

PJ Harvey – The Hope Six Demolition Project

I really enjoyed her music back in the day, but she kind of fell off my radar in recent times. My buddy Chunk highly recommended this new one, and I was glad he did. Her beautifully commanding voice remains on a righteous pedestal, and the album’s mostly gloomy vibe is right up my alley.

Run the Jewels 3

I’m still getting to know this Christmas miracle, but I already like it more than Run the Jewels 2, which I didn’t think was possible. This hip hop powerhouse only seems to be getting better and better, making some of the most important music for our times.

And the rest of what I really enjoyed in 2016:

David Bowie – Blackstar

Nine Inch Nails – Not the Actual Events

A Tribe Called Quest – We Got it From Here…Thank You 4 Your Service

WHOOP-szo – Citizen’s Ban(ne)d Radio

Black Mountain – IV

Testament – Brotherhood of the Snake

Saul Williams – MartyrLoserKing

Jim Bryson – Somewhere We Will Find Our Place

Beyoncé – Lemonade

Aesop Rock – The Impossible Kid

Deftones – Gore

Dillinger Escape Plan – Dissociation

Metallica – Hardwired…to Self Destruct

Radiohead – A Moon Shaped Pool

What was your favourite music from 2016?

November 10, 2016

Moon of the Crusted Snow

I’m very excited to announce that my next novel, Moon of the Crusted Snow, will be published by ECW Press in the fall of 2018. It’s a post-apocalyptic thriller that takes place in an isolated First Nation in northern Ontario. I posted a story synopsis on my Facebook page that you can read below:

When I started developing this idea a couple of years ago, I originally intended it as a short story. But the more I thought about it, the more it grew. I began writing in September 2015 during the two-week Indigenous Writers Program at the Banff Centre, and I’ve been able to keep a steady writing momentum over the past year thanks to kind grants from the Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts. My employer, CBC Ottawa, has graciously granted me leaves of absence to accommodate the creation of this novel. And just this fall, ECW acquired the publishing rights. I’m extremely grateful to these organizations for this opportunity.

Moon of the Crusted Snow is a novel about the end of the world as we know it. I described it above very simply as a “post-apocalyptic thriller”, and that’s likely how it will be billed going forward. But it’s much more than a story about the apocalypse and its fallout. It’s about resilience, self-discovery, and renewal. Without giving too much away, an important underlying theme in the story is how one community’s collapse could be another community’s new beginning.

Onaabenii Giizis: Anishinaabemowin term that translates into “crusted snow moon”, which can refer to late March on the calendar

— Waubgeshig Rice (@waub) October 18, 2016

But there is a great deal of darkness through which the characters in the story have to find light. It’s a harrowing struggle through the harshest season. The unwavering desire to survive is what has always drawn me to post-apocalyptic novels, and some of those classic stories inspired me to write my own, but through an Anishinaabe lens. I hope you’re able to read it when it’s published. Stay tuned for more details in the lead-up. Miigwech!

July 31, 2016

20 Jahre Nachher/20 Years Later

At Toronto’s Pearson International Airport on July 31, 1996

I struggled to put on a brave face and hold back tears in front of passing strangers at Pearson as I hugged my family one last time. We wouldn’t see each other again for a whole year, and I was about to embark on a journey that would change the course of my life. It was 20 years ago today – July 31, 1996 – and I was 17 years old with my world about to blow wide open.

My luggage was checked, my documents were secure in my travel wallet, and prolonging the farewell would only result in awkward crying. There was nothing left to do or say, so I turned to walk towards the international gate, waving one last time and taking a mental snapshot of the quivering smiles on the faces of my loved ones.

Months earlier, I was selected by the Rotary Club of Parry Sound to take part in the Rotary International Youth Exchange Program and spend a year in northern Germany. It was a pretty big deal for an Anishinaabe kid from a small reserve on Georgian Bay. It wasn’t really planned; I literally stumbled upon the opportunity when I saw a poster for the program in the hall at Parry Sound High School, which piqued my interest. It was a crucial time in my life: the waning months of Grade 12 when high school students were supposed to formulate an educational and career path before the now-obsolete OAC year.

But instead of getting ready for my last year of high school, I was now about to board a plane to a European country, not to return until the following summer to prepare for OAC in the fall, and hopefully have a clearer vision of career ambition. I was both nervous and excited about the foreign path ahead of me, but I couldn’t have anticipated just how it would shape the person I was to become. The tears were long buried as I buckled into my seat on the plane.

The months in the lead-up to my exchange were full of Rotary orientations, visits with family and friends, and learning as much about modern-day Germany as possible. I had tapes and books to learn the language, but admittedly, I barely listened to or read any of those (although I did learn German fluently while there). But one conversation I had in those final months in Canada stands out as truly momentous and ominous.

I got a call sometime before I left with a sort of job offer. I don’t remember exactly when it was, because it has been 20 years, and details aren’t as sharp. Either way, it was from the Anishinabek News, the newspaper published by the Union of Ontario Indians (now the Anishinabek Nation) to serve its 40-plus communities across the province. The editor said they had heard about my upcoming trip, and wondered if I’d be interested in writing about my experiences as a ‘Nish teen in a European country for publication every month. And he said they’d pay me for each story.

The notion of being paid to write blew my mind. I had no idea that was possible. Journalism was never presented as a viable career option to me, mostly because I hadn’t been exposed to the few Indigenous journalists at the time who were out there blazing a trail in Canadian media. And the main reason I applied for the exchange program in the first place was that despite being an honours student in high school, I didn’t know what I wanted to do for a living, or what or where I wanted to study for college or university.

At the Berlin Wall in November 1996 with fellow exchange students Lisa Hill and Jen Ottaway

That’s why, after attending the information session for the Rotary exchange program the day after seeing that poster in the hall, I thought it was a good option to keep those big decisions at bay, and take the opportunity to figure out my path during a year away from home in a far-off place. My parents were supportive, as were the rest of my family and the wider community around me, especially the people in my home of Wasauksing First Nation. I didn’t realize then that I would become an ambassador for Anishinaabe people especially, and not just the country of Canada. That role emerged in the writing I was about to do.

In early August, I began the German equivalent of high school in the town of Brake in the maritime lowlands of the northeast. My host sister Anne drove me to the front door of Gymnasium Brake, and I had never been so nervous in my life. Those nerves were exacerbated by the dozens of students gathered out front. They all stared as I got out of the car, and my gut teetered on fear.

But as I approached, I saw affability and enthusiasm in their eyes, and they welcomed me warmly. I learned later that they gathered there that morning because they heard there was an “Indianer” coming to their school. They wanted to see how I looked. My friend Tim later told me they were disappointed to see me arrive in jeans and a t-shirt with short hair. They were expecting a “real-life” Indian like the ones they read about in the Winnetou tales by Karl May. We laughed, and I wrote about that for one of my first assignments for the Anishinabek News.

It’s a story I tell often nowadays when I explain how I got into journalism and decided to make raising awareness of Indigenous experiences in Canada my life’s mission. Up until that point in my life, I had never encountered such a great degree of enthusiasm and general interest in my Anishinaabe background. Most people I met there valued my heritage and experiences, and wanted to know more. Back then, outside of my own non-Indigenous family, that just didn’t happen to me in Canada.

That made the cultural and social divide between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians even clearer to me. I was well aware of the racism and general ignorance that existed in my home country because I had lived it first-hand, growing up in the 1980s and 90s. It took going to Germany to really feel celebrated and appreciated outside of my own community, and that was a shocking eyeopener.

The more I thought about it, thousands of kilometres from home, the more I realized Canadians just weren’t learning the proper story of Indigenous peoples and the actual history of how Canada came to be. And it wasn’t the fault of everyday Canadians themselves. It was the education system itself that erased those truths and experiences. While I alone could never fix those problems, I could help raise awareness by writing about them.

“We don’t live in a tipi” – article in the Nordwest Zeitung newspaper following my speech (in German) to the Rotary Club of Brake in May 1997

There were more eyeopening experiences like that first day of school. There was the time I was at an anniversary party for my host parents when an elderly German man told me to be proud of who I was as an Anishinaabe person and to ensure that my culture stayed strong. He said because when he was my age, he was forced to salute a man named Hitler and fall in line with all his horrible beliefs. As such, he said he found it hard to feel proud of his German background later in life. I wrote about that interaction, too.

I began getting letters from people back home who read those stories. They thanked me for sharing my experiences, and for representing the Anishinaabeg a world away from our homelands. Feedback like that was heartwarming and motivating. It made me realize that this kind of storytelling could have a real impact. That’s when I decided I wanted to become a journalist.

The year in Germany wrapped up, full of many beautiful, compelling, and enlightening stories. I could write a whole book about how that exchange year unfolded and what it really means to me. But 20 years to the day that I left, I’ll just focus on how it helped define my career and my desire to share the important stories of Indigenous people and the issues that impact them.

I returned to Canada at age 18, had one last year of high school to go, and applied to journalism school. I got into Ryerson, graduated four years later, and have worked in different storytelling capacities since. It’s an honour and a privilege to do this for a living, and I don’t believe I would have found this life without that year in Germany.

I’ve looked back often. I’ve even gone back twice to visit, and I’m long overdue for a return. It will always be like another home to me. It’s where I found my path, which continues to take shape. And for that, I’ll always be grateful.

Danke schoen/chi-miigwech/thank you!

Thanks to the following who made that year possible: my parents and brothers, my friends and family in Wasauksing and Parry Sound and beyond, the Rotary Club of Parry Sound, the Rotary Club of Brake-Unterweser, the Heitzhausen family, the Kordes family, the Doeding family, the Koehlers, the Funks, staff and students of Gymnasium Brake, the lovely people of the Wesermarsch, Dave Dale and Maurice Switzer of the Anishinabek News, and all Rotary exchange students I met. You’ll all have a special place in my heart always.

March 15, 2016

Helpful habits for the author with a day job

For any author that relies on a primary career/day job for steady income, writing really is a labour of love. It means rearranging your life outside of your usual work routine to accommodate your passion for literary endeavours. That can result in sacrificing free time and activities to get writing done. But to better manage time and sustain a healthy, balanced, and happy life, I try to stick to a few simple habits that help me make progress and keep me creatively satisfied.

Make a routine and stick to it

Working eight hours or more a day can be daunting, and it’s sometimes hard to figure out when to write around that schedule. I’m very fortunate to have a creatively fulfilling career as a journalist with CBC, but after filing a story at the end long day, there’s not much gas left in the tank for creating fiction when I get home. So I set aside at least an hour for writing every morning before I go to work. The amount of words I get on the screen in that time varies – from as little as a paragraph to as much as a couple of pages – but I leave the house every day satisfied that I got something done. Depending on when in the day works best for you, try to stick to a set amount of time for writing as part of your daily routine.

Change up the venue

Because most of my writing happens in shorter spurts during the week, it can be difficult to transition into a longer, more relaxed pace on the weekend or a day off. I admit that my attention span isn’t vast enough to stay in one place all day, so when I have a wider window for writing, I like to work in different spots. I’ll start at home, and after taking a break to eat or for other obligations, I’ll head out with my laptop to a coffee shop, the local library branch, or a nearby pub. Breaking up those marathon sessions is always refreshing, especially if it takes me to a stimulating venue that caters to my mood. Give it a shot!

If you can’t write, think about writing

A daily routine can be complicated with a wide array of responsibilities, so outside of committed writing time, it’s often difficult to find ways to get words on the page or the screen. So I always make sure I’m at least thinking about writing when I can. Whether that’s on my walk to work (15 minutes in each direction), on my coffee or lunch break, in line at the store, or driving around the city, I’m contemplating where my story’s going and how I want to write it. I find that refining those ideas in my head makes a more efficient and effective writer when it comes time to sit down.

Get moving

Piling the creative process on top of a job and other life commitments can sometimes make everything very overwhelming, especially if you hit a wall in the creative process. When things get a little to stressful, I like to hit the reset button by going for a run, hitting the gym, or practicing martial arts. Blowing off steam is a great mental equalizer, and always clears my head enough to get back to writing. Even just a short walk through the neighbourhood does the job. As an added bonus, exercise can keep you healthy! Who knew?

Art begets art

Sometimes the greatest inspiration is enjoying someone else’s creativity. Whether it’s taking in live music, attending a reading, watching a play, or visiting an exhibition, an evening or afternoon out to enjoy the arts can help kickstart the internal word machine. I always make time for all kinds of shows, and I find when I get home, I’m always motivated to write. Also, having fun is always important!

These are just a few habits that keep me writing, and they’re by no means a perfect formula. But if you’re an author with a busy schedule, you may find some of these tips helpful. Write well!

I think I’m well beyond the halfway point now… #workinprogress

A photo posted by Waubgeshig Rice (@waub) on Dec 2, 2015 at 1:34pm PST