Randy Brown's Blog, page 5

September 6, 2019

Poetry Book Review: 'Hail and Farewell'

Poetry Book Review: "Hail and Farewell" by Abby E. Murray

Poetry Book Review: "Hail and Farewell" by Abby E. MurrayIf poet Abby E. Murray were to describe in social media terms her relationship with the U.S. Army, it would probably be "it's complicated." She might love the Army, but only because her husband loves it. She doesn't always feel welcomed by it. And she definitely doesn't trust it.

Because, ultimately, the Army's job is to break things and hurt people. And who wants that?

Murray's first book, the recently published and prize-winning "Hail and Farewell," is a collection of quirky, sometimes snarky, but always genuine explorations of Murray's relations to the Army and its cultural traditions, and with her active-duty soldier husband. It also notably interrogates struggles with pregnancy and parenthood. Some of the latter take place in the context of military family life, but one need not limit oneself to war to talk about conflict.

Like a cat, Murray chooses carefully when to engage a topic directly. Sometimes, she toys with it. Other times, she swats it off the table. Perhaps for reasons. Perhaps just to see what your reaction might be.

The collection's title evokes the tradition of sending-off soldiers to new assignments and locations with a small, informal ceremony. In many units, this is combined with a welcome of incoming personnel. In any form, such events are bittersweet milestones in the lives of individuals, but also of an organization. People come, people go, but the Army goes marching along.

In Murray's poems, such moments can variously take on the mythic tones of Catullus' "I salute you … now good-bye," to absurdism more in character with Groucho Marx's Captain Spaulding: "Hello, I must be going." For the most part, however, she aims at center-mass: good-humored, but unsentimental.

For example, Murray sets the stage for one ceremony in the collection's titular poem. Note the low-key commentaries present in "plastic tube" and "pub food," and in the commander's use of names, as well as the double-edged brilliance of "as if we are family":

Each time you are issued new ordersExposing more bite, she muses on a similar event in the separate poem "Hail and Farewell as a Junkyard Dog":

your current duty station hosts a Hail and Farewell:

the ceremony during which you receive a plaque

and I am given a rose in a plastic tube.

You make a short speech, your commander calls me

by your last name and rank, then we eat pub food

for the last time with the battalion as if we are family.

Every year, my colleagues ask what this means,

my friends whose jobs hail them by issuing paychecks

and say goodbye by letting them leave. […]

The colonel and his wifeMurray elevates this mix of awkwardness and affection to the sublime, when the "junkyard dog" pivots to again consider her husband. She is not there to be contrary, or to knock over punch bowls. She is there for reasons. And those reasons have little to do with the military.

are being sent to Fort Hood.

At their Hail and Farewell

I sit in the corner, a junkyard dog

on the overstuffed armchair.

The captain's wife asks me

if by going back to school

I will become a real doctor

or just the kind that writes.

Because I am a dog, I growl.

I do unladylike things:

show my teeth when I smile,

answer to my own whistle. […]

[…] I sit next to my husbandSuch a blend of mutual love and quiet regard seems worthy of its own ancient Greek nomenclature. Or perhaps there is an untranslatable German word, for something like "clear-eyed romance."

who is not a junkyard dog,

who smiles like he means it.

He places one finger

on the soft spot behind my ear

and I can hear his skin

telling me I've been so good.

Padding about on cat's paws throughout her collection, Murray similarly navigates a number of hard-fraught cultural practices in today's modern military. How married couples fretfully meet-up halfway around the world, for example, in the middle of a spouse's combat deployment. And the stuff-and-sputter of homecoming ceremonies. And "reintegration" seminars. Marriage-resilience workshops. Formal-dress Army birthday celebrations.

Murray's is a unique and wonderfully nuanced voice, in a growing klatch of unique and wonderfully nuanced voices: poets who happen to be related to war by marriage.

(For this reviewer, those voices include Jehanne Dubrow and Amalie Flynn, who write from their family experiences with the U.S. Navy; Lisa Stice, who writes from family experiences with the U.S. Marine Corps; and Elyse Fenton, who writes from family experiences with the U.S. Army. To this list add Lynn Marie Huston, who has published poetry about a relationship with a deployed soldier; and Charlie Bondhus, who has written about a relationship with a U.S. Marine. For a list of poetry written about 21st century wars involving the United States, visit here.)

Notably, Murray is the editor of Collateral journal, the mission of which is to draw attention to "the impact of violent conflict and military service by exploring experiences that surround the combat zone." She is more than a believer in poetry, she puts words into action. She teaches rhetorical writing techniques to Army officers, and poetry workshops to children held in detention centers.

It is no surprise then, that Murray hopes that her words and example will inspire others to take up pen and action. She dedicates her 99-page collection to other military spouses, "who see what happens during and after war, especially those still searching for their way to speak." In the back of the book, she notes, "My husband's experiences in the military and in combat have influenced my career as a poet and teacher. He operates in a culture that doesn't truly see me, and he has struggled, mostly with success, to question that."

Empathetic to both sides in the civil-military conversation, Murray keeps her observational barbs sharp, but cheery—she's like a Mary Poppins in combat boots. More often than not, her poems suggest a collaborative or confidential tone, rather than one of confrontation. For example, as she breezily starts her poem "International Women's Day":

The world observes my sexAnd this, from "How to Comfort a Small Child," a list of found and received advice on how best to act as a military parent:

on the same day America

celebrates the pancake,

and who doesn't love a good pancake?

[...] Make friends with womenWhere Murray stands out, above, and apart, however—where she "exceeds the standard," if you will—is in the way she tempers comparatively overt critiques of military culture and militarism, without tamping down her senses of humor, patriotism, or Storge (... und Drang?). In her longer poem "Happy Birthday, Army," she writes, for example:

who understand, women

with children and spouses

who haven't called in days.

When your daughter

flushes her plastic fox

down the toilet

and says he went to Afghanistan,

don't read into it.

Call a plumber.

[…] a woman's voice whispersMurray's depictions and images are intimate, her stories memorable, and her emotions immediate and accessible. With a feline grace, Murray reveals herself in glimpses, until you are comfortable with her work, and it is comfortable with you.

from beneath the howitzer,

the rented microphone

on fire with song:

Happy birrrthday, dear arrrmy

a la Marilyn Monroe,

and we are all a bunch of JFKs,

in our lace and heels

and cummerbunds and cords.

We watch a five-tiered cake

piped in black and gold buttercream

being pulled between our tables

by a silver robot

and shrug into the silk of knowing

we could end all this

with the flick of a finger

if we wanted.

When you achieve a certain level of mutual regard, it may curl up with you and purr. Other times, it may still scratch.

Because it is complicated.

Published on September 06, 2019 08:00

August 30, 2019

Poetry Book Review: 'Battle Dress'

Book Review: "Battle Dress" by Karen Skolfield

Book Review: "Battle Dress" by Karen SkolfieldWar poet Karen Skolfield is a U.S. Army veteran, an instructor of writing at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst; and, among other recognitions and prizes, a past runner-up in The Iowa Review's Jeff Sharlet Memorial Award for Veterans.

Skolfield's first poetry collection, 2013's "Frost in the Low Areas," contains precious few mentions of life in uniform. Notable samples from that work are the plain-spoken perspective of "Backblast Area Clear" and the hilarious "Army SMART Book: On Getting Lost."In her recently published second collection "Battle Dress," however, Skolfield fires-for-effect regarding her experiences with the military, fully and explicitly delivering on the rounds she first registered in "Frost in the Low Areas." The effort pays off for readers of both military and civilian backgrounds, accessibly and creatively exploring what it means to be soldier, and to be a woman at war.

Like the enlisted public affairs troop she once was, Skolfield takes aim at war with a photographer's eye for detail, a wicked sense of wordplay, and a soldierly love of others—even our younger selves—that can only be found in having shared the same foxhole. Her voice ranges from the mythic to the pastoral, from uncoded plain-text to battle-buddy confidential.

The 82-page book comprises 46 poems, presented across four untitled sections. Those who closely watch the "veterans-lit" space should recognize her byline: Skolfield has published widely; 41 of the poems have first appeared in literary journals.

The cover is a dusky, charcoal-and-buff vignette of clouds and dunes, which elegantly evokes one of Skolfield's longer works within, a dreamy mini-collection titled "Soldier Rendered as All Five Types of Sand Dunes." Rather than dwell long in such ethereal terrain, however, Skolfield is at her most sublime when she gets down and dirty.

In "Grenade: Origin, OFr. pomme-grenate," for example, Skolfield builds toward an epic momentum and a distinctively female view of the battlefield. As such, in this reviewer's opinion, it more than deserves to be read alongside Brian Turner's seminal 21st century war poem, "Here, Bullet."

Not as counterpoint, but as companion. One can imagine generating whole workshops from comparing and contrasting the two.

Turner's celebrated poem, after all, is full of the expected viscera and violence of combat, expertly placed in the body and mind of a soldier. The brutality is penetrative. Skolfield's poem likewise carves for readers a resonant space within which to experience a soldier's body and mind. Where Turner starts with a bullet, Skolfield throws a grenade. The results are no less explosive, or devastating.

[…] In mythology, every seed a monthSkolfield's "Grenade" is further enriched by an adjacent poem "The Throwing Gap". Winner of a 2016 Jeffrey E. Smith Editors' Prize from The Missouri Review, the poem illuminates Basic Training gender politics in a more journalistic mode. Skolfield writes:

of hell for the mother, the daughter,

her daughter's daughters

along the generations. In every war,

the same recognizable hunger.

Fruit of the dead, from living to not living,

also fruit of fertility, from one to many,

the names of the dead ripening.

How the arm extends, the palm opens,

the red pulp within, the perfect arc.

What is sown cannot be called back.

We say bearing fruit and it is borne.

/ […] We willedSkolfield unpacks words like a rucksack, extra-large, one each. One of her techniques is to title poems after dictionary entries, or to reveal words as etymological sub-munitions within poems; "grenade," "enlist", "war," and "discharge" are a few examples. Another is the practice of quoting the Army SMART Book—a predecessor to the U.S. Army's Soldier's Manual of Common Tasks. In the latter, the prompts read as fragments from a religious text, or aphorisms from some tactically proficient spiritual guru. Some favorites? "Army SMART Book: Small-arms fire may sound like mosquitos" and "Army SMART book: This Page Left Blank Intentionally."

our arms to be boys, our shoulders

brutal and male, we thought of torsos

and hands that had beaten or punched

or strangled or slapped or headlocked

women that were us or looked

like us and we wanted that strength.[…]

[…] Let us throw these grenades so far

that the drill sergeant says

God, seeing hand grenades thrown

like that gives me a hard-on

and we who are now male will laugh

at the rightness of it and we will say Me too.

Skolfield occasionally also engages in controlled bursts of word-creation and -association, resulting in rapid-fire images and language. These moments not only serve as opportunities for her to contextualize military experience and jargon, but to help readers understand and inhabit those concepts emotionally. In "Private, PV2, Private First Class," for example, Skolfield begins …

From the Latin privare: to deprive,Note how effortlessly Skolfield blends military nomenclature and slang, with punchy references to pop art and cosmetics. Seemingly just as easily, she often generates poems prompted by the day's minor headlines. Instead of focusing on above-the-fold items, she teases the timeless out of smaller stories—the one that veterans would talk about. Examples include the poems "Soldiers 'Fun' Photo with Flag-Draped Coffin Sparks Outrage"; "CNN Report: Rise in Sexual Assaults, Reprisals in the Military (2016)"; and "CNN Report: Symptoms of PTSD Mimic Lyme Disease." From the latter:

fullsleep and showers, homethoughts,

other gender except that one dance

stomping in bivvie and combat boots

most of us decked Birth Control Glasses

woooo those things worked.

[…]

Camo paint gumming up our pores,

jungle palette: vineknot, humus, treetangle.

Pvt. Morales painting cheekbones

like Escher drawings.

If viewed one way were were women;

in another darkbirds winging into light. […]

/ […] Stop moping, get out more,How easy and wonderful and terrifying is Skofield's medical safety brief! In the field, soldiers are trained to watch out for ticks, which can carry disease, and to report and document any bites. Less understood and appreciated is Post-Traumatic Stress. Both Lyme disease and PTSD can be silent killers, years after the inciting exposure. Lesser hands would let the facts fall flat. Skolfield's inspired act is to not only report the connection, but to re-create it as metaphor, and to make the metaphor available to help educate others: Lyme Disease is like PTSD; PTSD is like Lyme Disease.

all in your head, you're home now,

you're safe, family to consider;

the meds, the weight gain,

the loss, the breathless, the rasp of it.

No magic bullet: tell me about it.

Sometimes a rash like a target

so loved by marksmen.

Despite everything, breath goes out

and is pulled back in.

Remember to check your buddies.

Ideally, Skolfield's presence on the literary battlefield will help illuminate for editors, publishers, and other veterans the potential for more diverse collections of 21st century war poetry. In the meantime, her must-read "Battle Dress" delivers a keenly observed, hard-fought, and accessible perspective on military service, and making peace with oneself in a time of war. Most importantly, it provides useful images and tools with which to promote discussions between both "military" and "civilian" audiences.

Share it far and wide. Then wait for the fireworks. Because what is sown cannot be called back.

Published on August 30, 2019 03:00

August 8, 2019

Poetry Book Review: 'murmurs at the gate'

Poetry Book Review: "murmurs at the gate" by Suzanne S. Rancourt

Poetry Book Review: "murmurs at the gate" by Suzanne S. RancourtPoet Suzanne S. Rancourt is a multi-modal artist who lives and works in the American Northeast. She is a veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Army, with periods of active-duty and reserve service both prior to the first Gulf War and following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Some of her ancestors are Abenaki and Huron. Others are European. In her poetry, she honors both.

Rancourt is a practitioner of Aikido, a martial art that leverages an opponent's momentum against one's foes. She has experiences and certifications in various techniques of healing and recovery. In addition to a Master of Fine Arts in poetry, she holds a graduate degree in educational psychology.

In person, Rancourt is sly and stubborn, independent but quick to offer trust. In stories, she is celebrated for wearing red Chucks under her ceremonial garb. She carries a metaphorical long knife against inauthenticities and inequalities, which she readily draws with a slow grin. She is the embodiment of your favorite, rebellious aunt—the one person you should always seek out at a party, or in times of crisis.

One of her favorite forms of communication is a jab of insight or advice, delivered just under a rumble of conversation elsewhere in the room. Examples, taken from my own acquaintance: “Make sure to talk to him. He is an Elder.” “Never piss off a Lakota woman.” “It is time for you to take over for me as poetry editor.”

Each time, a smile at the surprised reaction she’d provoked.

Rancourt's second collection of poetry, “murmurs at the gate” (Unsolicited Press, 2019), explores themes of survivorship, as well as service to country, family, and community. (Her first collection was 2004's “Billboards in the Clouds,” Curbstone Books.) The 200-page book comprises 136 poems, presented across four untitled sections.

Her favored images are culturally broad, taken from the poet's life experiences and travels, family history and heritage. They include such disparate elements as backbones and bears, trains and tea, Buddhas and Babylon. The “gate” evoked by the collection's title can variously be read as a window to the ancient world, an opening in the veil between life and death, and the threshold to perception. While some of her topics are gritty and plain-spoken—particularly those regarding violence and women—Rancourt keeps focus on learning and healing, and singing songs of resilience.

In short, from her life and travels, Rancourt has successfully woven a rich and accessible mythology. In each poem, she variously shares a hit of wisdom, an insight to Otherness, or a potentially useful parable. As she writes in one poem (“Mish’ala”), “[…] My story is a poppyseed of delicacy, a peppercorn of truth, / an onion flake of— / salt”.

In the beginnings of another, “the final round,” she spits:

i load my gatling mouth with wordsRancourt's military service is ever-present—a few poems even explicitly regard narratives of service, war, and remembrance—but does not center the collection. Instead, her military experience and vocabulary are organic—a seamless part of her larger poetic palette. This is the voice of an artist-veteran who has confidently reengaged with society and her communities, rather than remain aloof and apart from them. Note, for example, how effortlessly she buries "pressure plate" into the rich, sensory descriptions of “Grampa's House”:

i sport ammo belts of documentation, certification

and identification criteria

pyres of brass shells gather ’round my feet

commemorative paraphernalia

strung together as a story wampum […]

We would walk through the once-horse-stall-hog-pen-now-garageEven those poems that more directly relate to military service do so in ways that build bridges. In “The Reticent Veil,” for example, one need not be familiar with tribal practices or terms, in order to appreciate the universal:

into the tool shop—our shoed feet scuffed tin shavings and sawdust

under wooden work benches soaked with bar oil, pine

and cool dampness. We walked through another door

into the summer kitchen across the Andy Warhol linoleum,

through the scent of mothballs

our weight triggering like pressure plates

the pumpkin pine floorboards that rattled

the stacked tin buckets made

by Great-Great-Grampa Daniel from Scotland

and Grammy’s bottle collection from years of dump digging adventures

[…] they all came back at CeremonyOne of Rancourt's most-notable forms, at least to this reviewer, seems her own take on haibun—a narrative or image that ends with a related haiku. Quoted here in abbreviated form, the poem "How much guilt?" provides an example:

when me and a Dance brother folded the flag

for the last time on the last day that he handed to me

in a shape that brought it all back to twenty years before

standing on the hillside, looking over Wilson Lake

dress blues, rifles, and Corfam dress shoes cracked

the unusually frigid December where a flag was folded

and handed to me in a shape

that equaled the grief of the world

which came and went as concrete and steel crushed as

the bones and dust I wake up chewing

and it all came back

when me and a sister held taught

a Grande Parade of a royal blue silk veil

maintaining reticent tension—

lovers and wives of warriors, sisters of warriors,

mothers of sons who are warriors—

we folded sharp-angled silence with the precision of lock and load

we creased with steady cadence our losses and recognized each other

not letting go

of the fabric the wind claims for a moment

and my words fluttered

“This is not a flag we are folding.”

Gold highlights in her hair beckon like the heart of Buddha.Rancourt's poetry questions assumptions and authorities, providing wisdom without providing answers. No matter our own life experiences, her latest collection offers gifts on every page. All we need do is to listen. To the stories. To the songs. To the voice under the voices.

A star—ancestral—pierced with suffering bled into a living tree

our only hope to ascend—go home—enter into, onto, a path of service. […]

Why do we continue

to search

the hearts

to bring home

our kind?

Leave no soldier behind

How long

do we search?

As long as it takes.

For as long as it takes.

Published on August 08, 2019 03:00

Poetry Book Review: "murmurs at the gate'

Poetry Book Review: "murmurs at the gate" by Suzanne S. Rancourt

Poetry Book Review: "murmurs at the gate" by Suzanne S. RancourtPoet Suzanne S. Rancourt is a multi-modal artist who lives and works in the American Northeast. She is a veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Army, with periods of active-duty and reserve service both prior to the first Gulf War and following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Some of her ancestors are Abenaki and Huron. Others are European. In her poetry, she honors both.

Rancourt is a practitioner of Aikido, a martial art that leverages an opponent's momentum against one's foes. She has experiences and certifications in various techniques of healing and recovery. In addition to a Master of Fine Arts in poetry, she holds a graduate degree in educational psychology.

In person, Rancourt is sly and stubborn, independent but quick to offer trust. In stories, she is celebrated for wearing red Chucks under her ceremonial garb. She carries a metaphorical long knife against inauthenticities and inequalities, which she readily draws with a slow grin. She is the embodiment of your favorite, rebellious aunt—the one person you should always seek out at a party, or in times of crisis.

One of her favorite forms of communication is a jab of insight or advice, delivered just under a rumble of conversation elsewhere in the room. Examples, taken from my own acquaintance: “Make sure to talk to him. He is an Elder.” “Never piss off a Lakota woman.” “It is time for you to take over for me as poetry editor.”

Each time, a smile at the surprised reaction she’d provoked.

Rancourt's second collection of poetry, “murmurs at the gate” (Unsolicited Press, 2019), comprises themes of survivorship, as well as service to country, family, and community. (Her first collection was 2004's “Billboards in the Clouds,” Curbstone Books.) The 200-page book comprises 136 poems, presented across four untitled sections.

Her favored images are culturally broad, taken from the poet's life experiences and travels, family history and heritage. They include such disparate elements as backbones and bears, trains and tea, Buddhas and Babylon. The “gate” evoked by the collection's title can variously be read as a window to the ancient world, an opening in the veil between life and death, and the threshold to perception. While some of her topics are gritty and plain-spoken—particularly those regarding violence and women—Rancourt keeps focus on learning and healing, and singing songs of resilience.

In short, from her life and travels, Rancourt has successfully woven a rich and accessible mythology. In each poem, she variously shares a hit of wisdom, an insight to Otherness, or a potentially useful parable. As she writes in one poem (“Mish’ala”), “[…] My story is a poppyseed of delicacy, a peppercorn of truth, / an onion flake of-- / salt”.

In the beginnings of another, “the final round,” she spits:

i load my gatling mouth with wordsRancourt's military service is ever-present—a few poems even explicitly regard narratives of service, war, and remembrance—but does not center the collection. Instead, her military experience and vocabulary are organic—a seamless part of her larger poetic palette. This is the voice of an artist-veteran who has confidently reengaged with society and her communities, rather than remain aloof and apart from them. Note, for example, how effortlessly she buries "pressure plate" into the rich, sensory descriptions “Grampa's House”:

i sport ammo belts of documentation, certification

and identification criteria

pyres of brass shells gather ’round my feet

commemorative paraphernalia

strung together as a story wampum […]

We would walk through the once-horse-stall-hog-pen-now-garageEven those poems that more directly relate to military service do so in ways that build bridges. In “The Reticent Veil,” for example, one need not be familiar with tribal practices or terms, in order to appreciate the universal:

into the tool shop—our shoed feet scuffed tin shavings and sawdust

under wooden work benches soaked with bar oil, pine

and cool dampness. We walked through another door

into the summer kitchen across the Andy Warhol linoleum,

through the scent of mothballs

our weight triggering like pressure plates

the pumpkin pine floorboards that rattled

the stacked tin buckets made

by Great-Great-Grampa Daniel from Scotland

and Grammy’s bottle collection from years of dump digging adventures

[…] they all came back at CeremonyOne of Rancourt's most-notable forms, at least to this reviewer, seems a her own take on haibun—a narrative or image that ends with a related haiku. Quoted here in abbreviated form, the poem "How much guilt?" provides an example:

when me and a Dance brother folded the flag

for the last time on the last day that he handed to me

in a shape that brought it all back to twenty years before

standing on the hillside, looking over Wilson Lake

dress blues, rifles, and Corfam dress shoes cracked

the unusually frigid December where a flag was folded

and handed to me in a shape

that equaled the grief of the world

which came and went as concrete and steel crushed as

the bones and dust I wake up chewing

and it all came back

when me and a sister held taught

a Grande Parade of a royal blue silk veil

maintaining reticent tension—

lovers and wives of warriors, sisters of warriors,

mothers of sons who are warriors—

we folded sharp-angled silence with the precision of lock and load

we creased with steady cadence our losses and recognized each other

not letting go

of the fabric the wind claims for a moment

and my words fluttered

“This is not a flag we are folding.”

Gold highlights in her hair beckon like the heart of Buddha.Rancourt's poetry questions assumptions and authorities, providing wisdom without providing answers. No matter our own life experiences, her latest collection offers gifts on every page. All we need do is to listen. To the stories. To the songs. To the voice under the voices.

A star—ancestral—pierced with suffering bled into a living tree

our only hope to ascend—go home—enter into, onto, a path of service. […]

Why do we continue

to search

the hearts

to bring home

our kind?

Leave no soldier behind

How long

do we search?

As long as it takes.

For as long as it takes.

Published on August 08, 2019 03:00

June 13, 2019

Soldier-Poet Speaks at National Arts Event

The writer of the "Welcome to FOB Haiku" blog will be presenting as part of a panel at the 2019 National Convention for Americans for the Arts, Minneapolis, Minn. "Changing and Honoring the Narrative of Military Experience" will be presented from 1:45 to 3 p.m. Sat., June 15, at the Hilton Minneapolis, 1001 Marquette Ave., Minneapolis.

The writer of the "Welcome to FOB Haiku" blog will be presenting as part of a panel at the 2019 National Convention for Americans for the Arts, Minneapolis, Minn. "Changing and Honoring the Narrative of Military Experience" will be presented from 1:45 to 3 p.m. Sat., June 15, at the Hilton Minneapolis, 1001 Marquette Ave., Minneapolis.Randy Brown embedded with his former Iowa Army National Guard unit as a civilian journalist in Afghanistan, May-June 2011. He authored the 2015 poetry collection "Welcome to FOB Haiku: War Poems from Inside the Wire", and edited the 2017 journalism collection "Reporting for Duty: Citizen-Soldier Journalism from the Afghan Surge, 2010-2011."

Brown's essays, journalism, and poetry have appeared widely both on-line and in print. Since 2015, he has served as the poetry editor for the national non-profit Military Experience & the Arts' literary journal "As You Were." As "Charlie Sherpa," he writes about citizen-soldier culture at: www.redbullrising.com; about military writing at: www.aimingcircle.com; and about modern war poetry at: www.fobhaiku.com.

You can follow him on Twitter: @FOB_Haiku

Other panelists participating in the Saturday event include:

Blake Rondeau, Minnesota Humanities CenterBriGette McCoy, Women Veteran Social JusticeJay Moad, playwright and performerThe event will be facilitated by Marete Wester, senior director of policy, Americans for the Arts.

According to the description for the "Changing and Honoring the Narrative of Military Experience" discussion:

As the Forever War in Afghanistan continues, communities need to explore ways to help our returning Veterans reintegrate into their communities. The Minnesota Humanities Center empowers Veterans from all conflicts and wars to speak in their own voices through plays, discussions, literature and Veterans’ Voices. Writing Workshops are facilitated by military writers who are Veterans themselves, offering peer mentorship, instruction, and encouragement to those seeking to express the military experience through essays, poetry, and performance.Learning objectives are:

1. See how storytelling helps in the Veterans’ healing process, reentry and reintegration into their communities.

2. Discuss how writing can help bridge the “civilian-military gap” between the military and the people they serve.

3. Explore how using the humanities can foster dialogue between military and civilian populations.

Published on June 13, 2019 03:00

April 19, 2019

"FOB Haiku" featured on "Accept Your Gifts" Podcast

In recognition of National Poetry Month, author, speaker, and U.S. Marine Corps veteran Tracy Crow recently featured the work of fellow veterans and other poets on two installments of her 22-minute, twice-weekly podcast on writing and creating, "Accept Your Gifts."

In recognition of National Poetry Month, author, speaker, and U.S. Marine Corps veteran Tracy Crow recently featured the work of fellow veterans and other poets on two installments of her 22-minute, twice-weekly podcast on writing and creating, "Accept Your Gifts."Crow is the author of numerous works of non-fiction, memoir, and fiction, including the how-to text "On Point: A Guide to Writing the Military Story." She is the president of the non-profit MilSpeak Foundation, Inc., and recently announced her services as a literary agent. The podcast is available via Crow's website, as well as the Podbean application.

Part 1, click herePart 2, click hereFeatured poets include U.S. Army veteran Randy Brown ("Welcome to FOB Haiku"), Air Force veteran Eric Chandler ("Hugging This Rock"), and Army veteran Michael Lancaster.

In Part 1 of this week's podcast (No. 26 in the series), former F-16 fighter pilot Chandler delivers readings of three poems: "Slipping the Surlies," a parody of John Gillespie Magee Jr.'s "High Flight"; "Maybe I Should've Lied"; and "The Path Through Security."

In Part 2 of the podcast (episode No. 27), Brown reads three poems, "night vision"; "your squad leader writes haiku"; and "Whiskey Tango Foxtrot."

Later, in the same episode, Lancaster reads two poems, "Salt Ponds (Winter)" and "Hush."

Published on April 19, 2019 03:00

April 1, 2019

Listen Up, Maggots! It's National Poetry Month!

PHOTO BY: U.S. Army Sgt. Ken ScarThis post, written by the author of "FOB Haiku: War Poems from Inside the Wire," originally appeared on the Red Bull Rising blog April 6, 2016.

PHOTO BY: U.S. Army Sgt. Ken ScarThis post, written by the author of "FOB Haiku: War Poems from Inside the Wire," originally appeared on the Red Bull Rising blog April 6, 2016.When packing for one of my first training experiences with the U.S. Army, back in the late 1980s, I knew that free time and footlocker space would be at a premium. I could live without luxuries like my Walkman cassette player for a few months. I also wanted to avoid avoid too much gruff from drill sergeants. So I stuffed a paperback copy of Shakespeare's "Henry V" into my left cargo pocket, wrapped in a plastic sandwich bag, as my sole entertainment.

If nothing else, I thought, I'd work on my memorization skills. ("Oh, for a muse of fire-guard duty …") Little did I realize that so much of my brain would already be filled, starting those summer months at Fort Knox, Ky., with the nursery rhymes of Uncle Sam. Training was full of poetry. Sometimes, it was profane. "This is my rifle, this is my gun!" Sometimes, it was pedagogical. "I will turn the tourniquet / to stop the flow / of the bright red blood." There were even times that it was nearly pathological. "What is the spirit of the bayonet?! / Kill! Kill! Kill!"

These basic phrases connected us new recruits to the yellow footprints of those who had stood here before, marched in our boots, squared the same corners, weathered the same abuses. Every time we moved, we were serenaded by sergeants. Counting cadence, calling cadence, bemoaning that Jody was back home, dating our women, drinking our beer. We learned our lines, our ranks, our patches, our places as much by tribal story-telling than by reading the effing field manual. Even our soldier humor was hand-me-down wisdom, tossed off like singsong hand grenades. Phrases like, "Don't call me 'sir' / I work for a living!" and "You were bet-ter off when you left! / You're right!"

Nobody's quite sure why April got the nod as National Poetry Month. I like to think that it's because of that line from T.S. Eliot's "The Wasteland": "April is the cruelest month." Because that sounds like the Army. Besides, in springtime, the thoughts of every warrior-poet lightly turns to baseball; showers that bring flowers ("If it ain't raining / it ain't training!"); and the start of fighting season in Afghanistan.

Poetry, I recognize, isn't every soldier's three cups of tea. Ever since I entertained my platoon mates with Prince Harry's inspiring St. Crispin's Day speech, however, I've enjoyed sneaking poetry into the conversation. Perhaps more soldiers would appreciate poetry, were they to realize the inherent poetics of military life:

Every time you go to war, you are engaged in a battle for narrative. Every deployment—individually as a soldier, or collectively as an Army or nation—is a story. Every story has a beginning, middle, and end. Every story is subject to vision, and revision. History isn't always written by the victors, but it is re-written by poets. Treat them well. Otherwise, they will cut you.

Every time you eat soup with a knife, you are wielding a metaphor. Every "boots on the ground," every "line in the sand," every Hollywood-style named operation ("Desert Shield"! "Desert Storm"! "Enduring Freedom"!) is a metaphor that shapes our understanding of a war and its objectives. If you don't understand the dangerous end of a metaphor, you shouldn't be issued one.

(There's also a corollary, and a warning: As missions change, so do metaphors. In other words, when a politician trots out a new metaphor for war, better check your six.)

Every poem is a fragment of intelligence, a piece in the puzzle. A poem can slow down time, describe a moment in lush and flushed detail. It can transport the reader to a different time, a different battlefield. Most importantly, a poem can describe the experience of military life and death through someone else's eyes—a spouse, a villager, a soldier, a journalist. Poetry, in short, is a training opportunity for empathy.

Soldiers like to say that the enemy gets a vote, so it's worth noting that the enemy writes poetry, too. Like reading doctrine and monitoring propaganda, reading an enemy's verse reveals motivations and values. Sun Tzu writes:

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.Every time you quote a master, from Sun Tzu to Schwarzkopf, you are delivering aphorism. I liken the aphorism—a quotable-quote or maxim—to be akin to concise forms of poetry, such as haiku. In fact, in my expansive view, I think aphorisms should count as poetry. In the world of word craft, it can take as much effort to hone an effective aphorism than it does to write a 1,000-word essay. Aphorisms are laser-guided missiles, rather than carpet bombs. We should all spend our words more wisely.

Reading a few lines connects us to the thin red line of soldiers past, present, and future. Poetry puts us in the boots of those who have served before, hooks our chutes to a larger history and experience of war. The likes of Shakespeare's "band of brothers" speech, John McRae's "In Flanders Fields," and Rudyard Kipling's poem "Tommy" continue to speak to the experiences and sentiments of modern soldiers.

I am happy to report that more-contemporary war poets have continued the march.

Here's a quick list to probe the front lines of modern war poetry: From World War II, seek out Henry Reed's "The Naming of Parts." For a jolt of Vietnam Era parody, read Alan Farrell's "The Blaming of Parts." From the Iraq War, Brian Turner's "Here, Bullet." In this tight shot group, modern soldiers will no doubt recognize themselves, their tools, and their times. Here is industrial-grade boredom, an assembly line of war, punctuated with humor and grit, gunpowder and lead.

Want more? Check out print and on-line literary offerings from Veterans Writing Project's "O-Dark-Thirty" quarterly literary journal; Military Experience & the Arts' twice-annual "As You Were"; the "Line of Advance" journal; and Southeast Missouri State University's "Proud to Be: Writing by American Warriors" annual anthology series.

Finally, you can buy an pocket anthology of poetry, such as the Everyman's Library Pocket Poets edition of "War Poems" from Knopf, or Ebury's "Heroes: 100 Poems from the New Generation of War Poets." Stuff it in your left cargo pocket. Read a page a day as a secular devotional, a meditation on war. Or, pick a favorite poem, print it out, and post it on the wall of your fighting position or office cube. Read the same poem, over and over again, during the course of a few weeks. See how it changes. See how it changes in you.

Remember: It's National Poetry Month. And every time you read a war poem, an angel gets its Airborne wings.

*****

Randy Brown embedded with his former Iowa Army National Guard unit as a civilian journalist in Afghanistan, May-June 2011. He authored the poetry collection Welcome to FOB Haiku: War Poems from Inside the Wire (Middle West Press, 2015). He is the current poetry editor of Military Experience and the Arts' "As You Were" literary journal, and a member of the Military Writers Guild. As "Charlie Sherpa," he blogs about military culture at www.redbullrising.com and military writing at www.aimingcircle.com.

Published on April 01, 2019 03:00

December 10, 2018

'So It Goes' reprints 'Whiskey Tango Foxtrot'

The author of the war poetry collection "Welcome to FOB Haiku" has work recently reprinted in the 2018 edition of the Kurt Vonnegut Museum & Library's literary journal "So It Goes." The 2018 edition focuses on a theme of "Lonesome No More," and issues of mental health and social well-being.

The author of the war poetry collection "Welcome to FOB Haiku" has work recently reprinted in the 2018 edition of the Kurt Vonnegut Museum & Library's literary journal "So It Goes." The 2018 edition focuses on a theme of "Lonesome No More," and issues of mental health and social well-being.Randy Brown's poem "Whiskey Tango Foxtrot" previously appeared in Stone Canoe No. 11 (2017). Evoking movies respectively featuring Tina Fey and Deadpool, the poem relates a chance encounter following the death by suicide of a fellow Iowa citizen-soldier. It memorably ends with the line "everyone has their own war," an echo of a line often misattributed to the ancient Greek philosophers Philo or Plato. The original "Be pitiful, for every man is fighting a hard battle," was penned by the 19th century Scottish theologian John Watson, who wrote under the pseudonym Ian McClaren.

The "Lonesome No More" theme is inspired by Vonnegut's satirical 1976 science-fiction novel "Slapstick," in which American policy makers establish a social-support system that arbitrarily assigns people to extended "families." The museum and library recently concluded a year of "Lonesome No More"-themed programming, which included community-awareness events on mental health. The non-profit organization's "Lonesome No More" messages often featured a "Lonesome No More" campaign button drawn by Vonnegut himself.

Museum and library officials put the "Lonesome No More" effort into further context here:

We understand that you can’t get rid of loneliness just by getting rid of ‘aloneness.’ Kurt Vonnegut knew this; as a World War II veteran who was captured by the Nazis and survived the Allied firebombing of Dresden, Germany, he suffered from [Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder] and depression. He carried more than his share of loneliness throughout his lifetime, but that intense loneliness isn’t unique to people with PTSD or depression. It also affects people with other mental health concerns: anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, or even just sadness when being bullied or feeling like people just don’t understand.Past themes featured by the "So It Goes" literary journal include war and peace (2012); humor (2013); and social justice (2015). Brown's poetry has previously appeared in issues dedicated to creativity (2014); Indiana Bicentennial (2016); and "a little more common decency" (2017). Current and back issuesof the journal can be ordered via the library's on-line store here.

More than 50 percent of the content of each year's issue of "So It Goes" is generated by military veterans and families. Born on November 11--a date variously celebrated as Veterans Day, Remembrance Day, and Armistice Day--Vonnegut was an intelligence scout in the 106th Infantry "Golden Lion" Division. He was captured during the Battle of the Bulge, and his experiences as a prisoner of war (P.O.W.) informed his first novel, "Slaughterhouse Five." The book was published in 1969.

Published on December 10, 2018 03:00

November 16, 2018

New Work Asks 3 Questions about War

The author of "Welcome to FOB Haiku" has new work appearing in Collateral Journal Issue No. 3.1. The on-line journal—which twice annually publishes a mix of fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and art—"draws attention to the impact of violent conflict and military service by exploring the perspectives of those whose lives are indirectly touched by them."

The author of "Welcome to FOB Haiku" has new work appearing in Collateral Journal Issue No. 3.1. The on-line journal—which twice annually publishes a mix of fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and art—"draws attention to the impact of violent conflict and military service by exploring the perspectives of those whose lives are indirectly touched by them."Randy Brown's "tell me how this ends" is a short and simple poem, consisting of three questions. An accompanying biographical statement notes, "Many of [Brown's] recent poems, including this one, involve interrogating war and conflict as a parent of young teenagers. The phrase 'tell me how this ends' was popularized as a 2003 quote by then-U.S. Army Maj. Gen. David Patreaus regarding the Iraq War."

Other poets featured in Collateral Journal include: Jason Arment, Yvonne, L. Burton Brender, Holly Day, James Deitz, Thad DeVassie, Erica Goss, Faith Esperanza Harron, Sarah McCann, and John Sibley Williams.

Essayists Janet Gool and Catherine Elizabeth Puckett contribute non-fiction. John Petelle, David Gambino, and Donna Maccherone contribute short stories.

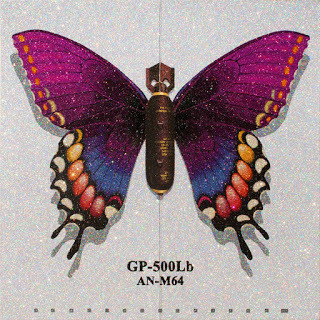

Graphics featured in Issue 3.1 are by Iranian artist Reza Baharvand, who also participates in a Q&A interview. "At first, I find an image of war, usually recent wars in the Middle East, from TV or the Internet," he says of his process. "It is important for me to paint war images completely, in detail, to emphasize that the images are existing in reality. I paint it realistically in large size, then scratch and destroy it. I scratch them in order to show how we ignore the truth. In the foreground, there are objects painted in glitter. They are objects from everyday life, but they are shiny and deceptive. The main issue is in the background."

Graphics featured in Issue 3.1 are by Iranian artist Reza Baharvand, who also participates in a Q&A interview. "At first, I find an image of war, usually recent wars in the Middle East, from TV or the Internet," he says of his process. "It is important for me to paint war images completely, in detail, to emphasize that the images are existing in reality. I paint it realistically in large size, then scratch and destroy it. I scratch them in order to show how we ignore the truth. In the foreground, there are objects painted in glitter. They are objects from everyday life, but they are shiny and deceptive. The main issue is in the background."

Published on November 16, 2018 07:30

November 9, 2018

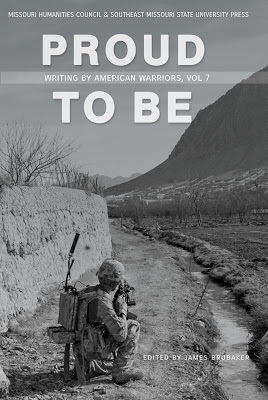

Poem is Finalist in 'Proud to Be' Vol. 7

Randy Brown, author of "Welcome to FOB Haiku," has a new poem featured in the forthcoming anthology "Proud to Be: Writing by American Warriors."

Randy Brown, author of "Welcome to FOB Haiku," has a new poem featured in the forthcoming anthology "Proud to Be: Writing by American Warriors."Published by Southeast Missouri State University Press, and underwritten by the Missouri Humanities Council, it will be the seventh volume for such work. The book is currently available for pre-order.

The 200-page volume features poetry, fiction, non-fiction, photography, and other content by and about U.S. military veterans, service members, and families. The series releases annually in November, to coincide with Veterans Day.

Brown's new poem, "the ground truth," regards the experience of observing media and recovery efforts surrounding Flash Airlines Flight 604, which crashed in January 2004, minutes after taking off from Sharm el Sheikh International Airport. Killed in the crash were 148 civilian passengers and crew. Brown connects the event to the 1985 loss of 248 U.S. soldiers and civilian air crew in Arrow Air Flight 1285 in a crash near Gander, Canada.

Brown's poem begins:

Our desert watch was almost overThe poem is recognized with an honorable mention in the anthology.

when charter Flight 604 banked steep

into the Anubis space

with 148 souls-on-board.

There was no moon.

The Red Sea was dark between

Herb’s Beach and the coming sun. […}

According to press materials, judges included:

[...] Emma Bolden (author of the poetry collections "House Is an Enigma", "medi(t)ations", and "Maleficae"); Seth Wade (BFA University of Dayton, MFA University of Cincinnati); Ron Austin (author of the forthcoming story collection "Avery Colt is a Snake, a Thief, a Liar"); Missy Phegley (director of composition at Southeast Missouri State University); and Philip MacKenzie (MFA from Minnesota State University, Mankato, and a PhD from the University of South Dakota).

Published on November 09, 2018 03:00