Howard Andrew Jones's Blog, page 47

March 30, 2015

Sword & Sorcery Musings

It seems that all I do with my writing anymore these days is revise. Back when I was writing in my teens and twenties I used to just keep picking away at the first three or four chapters of a work and never advance. Recently it seems like I get the first three or four chapters working pretty well but then take too long getting to the good stuff. No more. Just as I prefer streamlined role-playing game systems I’ve decided to strip away any sense of the padding I hate and get to the good bits right up front.

It seems that all I do with my writing anymore these days is revise. Back when I was writing in my teens and twenties I used to just keep picking away at the first three or four chapters of a work and never advance. Recently it seems like I get the first three or four chapters working pretty well but then take too long getting to the good stuff. No more. Just as I prefer streamlined role-playing game systems I’ve decided to strip away any sense of the padding I hate and get to the good bits right up front.

Regular readers of my blog might have seen me writing about parallel plot structures and all that recently, but despite my tinkering and tinkering I just couldn’t keep it interesting enough, so I’m gutting some work. An awful lot of work, really, but if the work isn’t really good, why subject my readers to it? I’m upset that I didn’t notice sooner, but I guess I’m glad my editor and wife and I noticed now, before it went to print. The next series needs to be better than competent. It needs to be me at my best. How long will it take to correct? I don’t know. If I’m really passionate, though, it shouldn’t take THAT long.

In other news, over the weekend I finally sat back with Primeval Thule and found it one of the finest game setting I’ve ever read. I hope they release a Swords & Wizardry version of it soon (due to me preferring simpler rules systems). I liked almost everything about it except the inclusion of halflings and dwarves, but a reader can simply replace them with human tribes. I loved what the writers did with the Elves — they have a real Melniboean vibe. Honestly, I don’t know that I’ve had this much fun reading a setting since I poured through Talislanta. The writers really GOT sword-and-sorcery and what makes it different from epic fantasy.

In other news, over the weekend I finally sat back with Primeval Thule and found it one of the finest game setting I’ve ever read. I hope they release a Swords & Wizardry version of it soon (due to me preferring simpler rules systems). I liked almost everything about it except the inclusion of halflings and dwarves, but a reader can simply replace them with human tribes. I loved what the writers did with the Elves — they have a real Melniboean vibe. Honestly, I don’t know that I’ve had this much fun reading a setting since I poured through Talislanta. The writers really GOT sword-and-sorcery and what makes it different from epic fantasy.

Speaking of which, I was leafing through some game books and it occurred to me that most of the old school role-playing games don’t get barbarians. Apart from Astonishing Swordsmen and Sorcerers of Hyperborea and Crypts and Things none of them seem to actually have read any Conan stories. They equate “barbarian” with “berserker.” Conan never once lost his cool and launched into a killing frenzy, but he did do lots of sneaking and climbing and wilderness stuff. The creatures of the aforementioned games are the only D&D simulators who do a good job of emulating that.

Speaking of which, I was leafing through some game books and it occurred to me that most of the old school role-playing games don’t get barbarians. Apart from Astonishing Swordsmen and Sorcerers of Hyperborea and Crypts and Things none of them seem to actually have read any Conan stories. They equate “barbarian” with “berserker.” Conan never once lost his cool and launched into a killing frenzy, but he did do lots of sneaking and climbing and wilderness stuff. The creatures of the aforementioned games are the only D&D simulators who do a good job of emulating that.

Speaking of Crypts & Things, the new revised edition is in its final day on Kickstarter, so swing by and sign in if you want to support a nifty rules system.

March 27, 2015

Swords Against Death Re-Read: “The Jewels in the Forest”

Bill Ward and I are re-reading a book from Fritz Leiber’s famous Lankhmar series, Swords Against Death. We hope you’ll pick up a copy and join us. This week we tackled the second tale in the volume, “The Jewels in the Forest.”

Bill Ward and I are re-reading a book from Fritz Leiber’s famous Lankhmar series, Swords Against Death. We hope you’ll pick up a copy and join us. This week we tackled the second tale in the volume, “The Jewels in the Forest.”

Howard: Coming upon “The Jewels in the Forest” for the first time in a quarter century was like sitting down at a warm campfire to hear a favorite tale. I recalled the gist of the events, but it didn’t keep me from enjoying the story all the way through. I was soon swept up into the adventure. It didn’t matter that I recalled the bones of the plot; the mystery beguiled me.

Fritz Leiber

Even in this embryonic stage of his career Leiber was already displaying masterful touches, and it was wonderful to see. I paid especially close attention to the able way he did something today’s writers are told is taboo: he shifted between viewpoints whenever he damned well pleased, without chapter or section breaks of any kind. He usually accomplished this by showing us the character through the other’s eyes before the shift, like a director changing camera angles.

Bill: I was impressed by that as well, a few times I read back a ways to see how he made it work.

Howard: That’s exactly what I did! I was enjoying what he was doing so much I had to slow down and read deliberately to pay closer attention to the techniques. Even from the outset, Leiber does so many things right that I feel a little guilty about calling out a handful of things he does wrong, but – here goes.

He’s still getting his feet wet a little with his narrative, so when we encounter the two heroes for the first time we get a fairly static description of them rather than a sense of them in action, almost as though the frame has frozen in the camera. That said, Leiber’s prose is so smooth he carries it off. More awkward is the somewhat stilted dialogue between the characters in the opening segments. That, though, begins to ease by the halfway mark.

Bill: After that introduction he gives us a fun action scene that lets us know that these guys really know what they’re doing, ducking the arrows as they are launched, Fafhrd stringing his bow on horseback and loosing an arrow at their pursuers.

Bill: After that introduction he gives us a fun action scene that lets us know that these guys really know what they’re doing, ducking the arrows as they are launched, Fafhrd stringing his bow on horseback and loosing an arrow at their pursuers.

Howard: Absolutely. He might state flat out that they’re veterans, etc., but then he shows it. But (sigh) I said I’d discuss some flaws, so I’ll mention a few more before I get back to discussing all the great stuff. The arrival of the priest, something else I didn’t object to in my earlier readings, is extremely convenient to the story, almost like something you’d see in a stage play. It begs a little much from the reader.

Bill: The priest was the one thing that stood out to me as a flaw. Introducing him earlier, perhaps even as exposition (the mad priest that, for example, tried to take the “treasure riddle” from them earlier, or who the peasants noticed hanging around the area) would have removed his coming out of nowhere, without diminishing the mystery of who he was (at first I thought perhaps he was the old wizard who built the treasure house himself, as I think was Leiber’s intention). I do wonder if Leiber’s original idea was to give Lord Rannarsh the privilege of running ahead and getting his skull smashed in the treasure chamber, but he couldn’t resist a bit more swordplay and so gave him to the Mouser to dual.

Howard: I like your suggestions. My only other big issue with the tale was near the end. As a kid I was confused when I tried to envision the conclusion, probably because I’d never read anything like it before. Now I could picture everything clearly, apart from the fact it seems like Fafhrd twice leaps through the doorway to escape. I read that sequence multiple times, and I can only conclude the first doorway is an exit from an inner chamber and the second is the exit from the tower… but it’s just not clear.

Howard: I like your suggestions. My only other big issue with the tale was near the end. As a kid I was confused when I tried to envision the conclusion, probably because I’d never read anything like it before. Now I could picture everything clearly, apart from the fact it seems like Fafhrd twice leaps through the doorway to escape. I read that sequence multiple times, and I can only conclude the first doorway is an exit from an inner chamber and the second is the exit from the tower… but it’s just not clear.

Bill: Yes, the domelike inner, treasure chamber, and then the doorway at the bottom of the stairs to the tomb itself. I felt as if the layout could have been somewhat more concrete as well.

Howard: Everything else is nearly smooth as silk. The action sequences are spare and exciting in every instance. I particularly love the fight with Rannarsh’s men outside the tower, opening with Fafhrd and the Mouser nearly tricking them into retreat. It’s full of all sorts of wonderful precise details, like Fafhrd having trouble holding off two antagonists and knowing that holding off four is complete nonsense you’d only find in a saga. Or the Mouser’s sword suddenly dropping from the trees to land point first between Fafhrd’s attackers.

Bill: That was also one of my favorite parts. I felt the whole thing was both grounded in realism and yet also very fun and colorful. I remember being struck by the same thought the first time I read it, it stood out that much. Their reactions after the battle also reinforce the realism of the events — neither simply shrugs off the heightened emotions of a life and death struggle, but both have their own personal way of dealing with them.

Bill: That was also one of my favorite parts. I felt the whole thing was both grounded in realism and yet also very fun and colorful. I remember being struck by the same thought the first time I read it, it stood out that much. Their reactions after the battle also reinforce the realism of the events — neither simply shrugs off the heightened emotions of a life and death struggle, but both have their own personal way of dealing with them.

And grounding it all in realism is a great balance for, firstly, the weird nature of the mystery and the ending — I’m not a historian of the genre, but I can’t imagine the “tomb as monster” idea was too common when this story appeared. But also for the characters themselves, they are larger than life, they enjoy adventure for its own sake, they are arch and clever. But they aren’t superhuman in a fight, they aren’t immune to fear, and they don’t always succeed.

Howard: There also are excellent moments of character that any number of literary descendants could stand to pay better attention to (there are just enough, rather than too few, or two many, and it’s a fine line): the Mouser, worried by some presentiment about the tower, plays on Fafhrd’s fear of snakes to lure him out, although he has to be clever about it; Fafhrd weeping over the man he killed in a sword fight; Mouser’s concern for the girl’s safety even over his lust for treasure. (They’re rogues, but they’re not villains.) I could go on, but my portion of this analysis is getting long already.

Bill: Exactly. I loved that we got such a sense of who they were in the story, and not merely in a cliched or archetypal way. The two of them entertaining the peasants was another marvelous instance of characterization for both of them.

Bill: Exactly. I loved that we got such a sense of who they were in the story, and not merely in a cliched or archetypal way. The two of them entertaining the peasants was another marvelous instance of characterization for both of them.

And Leiber’s wonderful cleverness is on display throughout. I’ll end with my favorite quote, the Mouser nervously remarking on all the skeletons littering the stairs of the treasure house: “Our hosts are overly ancient and indecently naked.”

Howard: Oh yeah, great line. There are plenty of great lines, but then there are even more in later stories. I bet if we were to take a highlighter to a Leiber text every time we spotted a great bit of dialogue, nearly half of this book would be yellow.

While I’m sure you and I could go on, there’s only one more thing I’ll mention, and that’s the opening: “It was the Year of the Behemoth, the Month of the Hedgehog, The Day of the Toad. ” Apart from the animals different from ones Harold Lamb would have used, this sentence reminded me of the beginning to any number of his Cossack adventure stories. I wish I knew if Leiber had read the adventures of Khlit the Cossack. Leiber would have been very young when those Cossack tales were first printed. Unless there were old copies of Adventure magazine lying around the house it’s unlikely Leiber could lay hands on them, because they weren’t reprinted until long after “The Jewels in the Forest” saw publication. Still, when I went from Leiber to Lamb I found that the two writers shared some similarities. It may simply be that good adventure writers draw from the same well even if they aren’t familiar with each other’s works, or that both Lamb and Leiber were imitating a common source.

Next week we’ll look at one that was always one of my favorites, “Thieves’ House.”

Swords Against Death Re-Read: “The Jewels in the Tower”

Bill Ward and I are re-reading a book from Fritz Leiber’s famous Lankhmar series, Swords Against Death. We hope you’ll pick up a copy and join us. This week we tackled the second tale in the volume, “The Jewels in the Forest.”

Bill Ward and I are re-reading a book from Fritz Leiber’s famous Lankhmar series, Swords Against Death. We hope you’ll pick up a copy and join us. This week we tackled the second tale in the volume, “The Jewels in the Forest.”

Howard: Coming upon “The Jewels in the Forest” for the first time in a quarter century was like sitting down at a warm campfire to hear a favorite tale. I recalled the gist of the events, but it didn’t keep me from enjoying the story all the way through. I was soon swept up into the adventure. It didn’t matter that I recalled the bones of the plot; the mystery beguiled me.

Fritz Leiber

Even in this embryonic stage of his career Leiber was already displaying masterful touches, and it was wonderful to see. I paid especially close attention to the able way he did something today’s writers are told is taboo: he shifted between viewpoints whenever he damned well pleased, without chapter or section breaks of any kind. He usually accomplished this by showing us the character through the other’s eyes before the shift, like a director changing camera angles.

Bill: I was impressed by that as well, a few times I read back a ways to see how he made it work.

Howard: That’s exactly what I did! I was enjoying what he was doing so much I had to slow down and read deliberately to pay closer attention to the techniques. Even from the outset, Leiber does so many things right that I feel a little guilty about calling out a handful of things he does wrong, but – here goes.

He’s still getting his feet wet a little with his narrative, so when we encounter the two heroes for the first time we get a fairly static description of them rather than a sense of them in action, almost as though the frame has frozen in the camera. That said, Leiber’s prose is so smooth he carries it off. More awkward is the somewhat stilted dialogue between the characters in the opening segments. That, though, begins to ease by the halfway mark.

Bill: After that introduction he gives us a fun action scene that lets us know that these guys really know what they’re doing, ducking the arrows as they are launched, Fafhrd stringing his bow on horseback and loosing an arrow at their pursuers.

Bill: After that introduction he gives us a fun action scene that lets us know that these guys really know what they’re doing, ducking the arrows as they are launched, Fafhrd stringing his bow on horseback and loosing an arrow at their pursuers.

Howard: Absolutely. He might state flat out that they’re veterans, etc., but then he shows it. But (sigh) I said I’d discuss some flaws, so I’ll mention a few more before I get back to discussing all the great stuff. The arrival of the priest, something else I didn’t object to in my earlier readings, is extremely convenient to the story, almost like something you’d see in a stage play. It begs a little much from the reader.

Bill: The priest was the one thing that stood out to me as a flaw. Introducing him earlier, perhaps even as exposition (the mad priest that, for example, tried to take the “treasure riddle” from them earlier, or who the peasants noticed hanging around the area) would have removed his coming out of nowhere, without diminishing the mystery of who he was (at first I thought perhaps he was the old wizard who built the treasure house himself, as I think was Leiber’s intention). I do wonder if Leiber’s original idea was to give Lord Rannarsh the privilege of running ahead and getting his skull smashed in the treasure chamber, but he couldn’t resist a bit more swordplay and so gave him to the Mouser to dual.

Howard: I like your suggestions. My only other big issue with the tale was near the end. As a kid I was confused when I tried to envision the conclusion, probably because I’d never read anything like it before. Now I could picture everything clearly, apart from the fact it seems like Fafhrd twice leaps through the doorway to escape. I read that sequence multiple times, and I can only conclude the first doorway is an exit from an inner chamber and the second is the exit from the tower… but it’s just not clear.

Howard: I like your suggestions. My only other big issue with the tale was near the end. As a kid I was confused when I tried to envision the conclusion, probably because I’d never read anything like it before. Now I could picture everything clearly, apart from the fact it seems like Fafhrd twice leaps through the doorway to escape. I read that sequence multiple times, and I can only conclude the first doorway is an exit from an inner chamber and the second is the exit from the tower… but it’s just not clear.

Bill: Yes, the domelike inner, treasure chamber, and then the doorway at the bottom of the stairs to the tomb itself. I felt as if the layout could have been somewhat more concrete as well.

Howard: Everything else is nearly smooth as silk. The action sequences are spare and exciting in every instance. I particularly love the fight with Rannarsh’s men outside the tower, opening with Fafhrd and the Mouser nearly tricking them into retreat. It’s full of all sorts of wonderful precise details, like Fafhrd having trouble holding off two antagonists and knowing that holding off four is complete nonsense you’d only find in a saga. Or the Mouser’s sword suddenly dropping from the trees to land point first between Fafhrd’s attackers.

Bill: That was also one of my favorite parts. I felt the whole thing was both grounded in realism and yet also very fun and colorful. I remember being struck by the same thought the first time I read it, it stood out that much. Their reactions after the battle also reinforce the realism of the events — neither simply shrugs off the heightened emotions of a life and death struggle, but both have their own personal way of dealing with them.

Bill: That was also one of my favorite parts. I felt the whole thing was both grounded in realism and yet also very fun and colorful. I remember being struck by the same thought the first time I read it, it stood out that much. Their reactions after the battle also reinforce the realism of the events — neither simply shrugs off the heightened emotions of a life and death struggle, but both have their own personal way of dealing with them.

And grounding it all in realism is a great balance for, firstly, the weird nature of the mystery and the ending — I’m not a historian of the genre, but I can’t imagine the “tomb as monster” idea was too common when this story appeared. But also for the characters themselves, they are larger than life, they enjoy adventure for its own sake, they are arch and clever. But they aren’t superhuman in a fight, they aren’t immune to fear, and they don’t always succeed.

Howard: There also are excellent moments of character that any number of literary descendants could stand to pay better attention to (there are just enough, rather than too few, or two many, and it’s a fine line): the Mouser, worried by some presentiment about the tower, plays on Fafhrd’s fear of snakes to lure him out, although he has to be clever about it; Fafhrd weeping over the man he killed in a sword fight; Mouser’s concern for the girl’s safety even over his lust for treasure. (They’re rogues, but they’re not villains.) I could go on, but my portion of this analysis is getting long already.

Bill: Exactly. I loved that we got such a sense of who they were in the story, and not merely in a cliched or archetypal way. The two of them entertaining the peasants was another marvelous instance of characterization for both of them.

Bill: Exactly. I loved that we got such a sense of who they were in the story, and not merely in a cliched or archetypal way. The two of them entertaining the peasants was another marvelous instance of characterization for both of them.

And Leiber’s wonderful cleverness is on display throughout. I’ll end with my favorite quote, the Mouser nervously remarking on all the skeletons littering the stairs of the treasure house: “Our hosts are overly ancient and indecently naked.”

Howard: Oh yeah, great line. There are plenty of great lines, but then there are even more in later stories. I bet if we were to take a highlighter to a Leiber text every time we spotted a great bit of dialogue, nearly half of this book would be yellow.

While I’m sure you and I could go on, there’s only one more thing I’ll mention, and that’s the opening: “It was the Year of the Behemoth, the Month of the Hedgehog, The Day of the Toad. ” Apart from the animals different from ones Harold Lamb would have used, this sentence reminded me of the beginning to any number of his Cossack adventure stories. I wish I knew if Leiber had read the adventures of Khlit the Cossack. Leiber would have been very young when those Cossack tales were first printed. Unless there were old copies of Adventure magazine lying around the house it’s unlikely Leiber could lay hands on them, because they weren’t reprinted until long after “The Jewels in the Forest” saw publication. Still, when I went from Leiber to Lamb I found that the two writers shared some similarities. It may simply be that good adventure writers draw from the same well even if they aren’t familiar with each other’s works, or that both Lamb and Leiber were imitating a common source.

Next week we’ll look at one that was always one of my favorites, “Thieves’ House.”

March 20, 2015

Swords Against Death Re-Read: “The Circle Curse”

In the coming weeks Bill Ward and I are re-reading a book from Fritz Leiber’s famous Lankhmar stories, Swords Against Death. We hope you’ll pick up a copy and join us. This week we tackled the first tale in the volume. “The Circle Curse” is really more of a prologue than a proper story.

In the coming weeks Bill Ward and I are re-reading a book from Fritz Leiber’s famous Lankhmar stories, Swords Against Death. We hope you’ll pick up a copy and join us. This week we tackled the first tale in the volume. “The Circle Curse” is really more of a prologue than a proper story.

Howard: When I first read “The Circle Curse” I was 14 or 15 years old and it left me wanting. So wanting that I probably would have stopped reading the book if the story hadn’t been so short. I had opened Swords Against Death expecting to be transported into adventure, and what I got in “The Circle Curse” was more the summary of several adventures, a whole lot of wandering, and a little moping. I loved the rest of the book and re-read it multiple times, but I have never, ever revisited this first story until now.

If you’re not already familiar with Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser this is a cold start. It doesn’t really tell a proper story, it just fills in the gaps between what happened between “Ill Met in Lankhmar” and the collection of tales here. And that’s perfectly fine, I suppose, if you’re reading them in sequence. Maybe readers need something to tell them what happened between adventures. I would have preferred a few more tales to tell me rather than this summary, but even creative geniuses don’t always give you what you want.

That said, I ended up liking the story better than I remembered. I certainly think it’s a more entertaining read if you’re already familiar with the characters.

Bill: The first time I read “The Circle Curse” it served its purpose as a bridging story between “Ill Met in Lankhmar” and the stories in Swords Against Death, and it didn’t really stick out one way or the other in my mind. However, that’s twice now that I can think of where the extra stories Leiber wrought for the “novelization” of the F&GM stories ran the risk of alienating potential readers. The two novella length origin story pieces from the previous book weren’t at all what I was looking for when I picked up the F&GM stories for the first time, and I’ve heard the same from at least one other online reviewer. If I hadn’t already read better, classic F&GM stories in other anthologies, I may have not realized what was around the corner.

Bill: The first time I read “The Circle Curse” it served its purpose as a bridging story between “Ill Met in Lankhmar” and the stories in Swords Against Death, and it didn’t really stick out one way or the other in my mind. However, that’s twice now that I can think of where the extra stories Leiber wrought for the “novelization” of the F&GM stories ran the risk of alienating potential readers. The two novella length origin story pieces from the previous book weren’t at all what I was looking for when I picked up the F&GM stories for the first time, and I’ve heard the same from at least one other online reviewer. If I hadn’t already read better, classic F&GM stories in other anthologies, I may have not realized what was around the corner.

I wonder what the genesis was of the need to assemble these pieces with connecting or prequel material was — if it was all Leiber, or if it was his editor?

That said, I really like “The Circle Curse” for what it is. I suspect if the condensed adventures mentioned in the story were part of a italicized block of text in a preface, maybe attributed to “The Nehwonian Chronicles,” it wouldn’t even bear much notice. As it is it and the two preface stories from the previous book stand out as different from the classic F&GM story, and it’s no wonder they give people pause.

One thing I think is interesting about the story is it actually assigns a consequence to F&GM’s previous adventure. The loss of their lovers isn’t something they just shrug off between adventures — they’re so distraught they vow never to return to Lankhmar! Some readers know, of course, that they have many more adventures set in this city, and of course it turns out that it is their curse to circle back to their starting point, but only after many foreign adventures have dulled some of their pain.

One thing I think is interesting about the story is it actually assigns a consequence to F&GM’s previous adventure. The loss of their lovers isn’t something they just shrug off between adventures — they’re so distraught they vow never to return to Lankhmar! Some readers know, of course, that they have many more adventures set in this city, and of course it turns out that it is their curse to circle back to their starting point, but only after many foreign adventures have dulled some of their pain.

But it isn’t just their pain that is necessary for Leiber to convey, but their career itself. Most everything in the previous book is fresh back story. There aren’t many off stage adventures implied with F&GM. But we know the guys in the classic F&GM canon have a long history together; they’re seasoned. “The Circle Curse” gives us that seasoning, taking the ill met pair and turning them into the two [who] sough adventure.

As for the story itself I really enjoyed some of the throwaway ideas for the duo’s adventures. They were pure Leiber, such as a realm grown so decadent and “far grown into the future” that all the men were bald! The various jobs the two hold while adventuring are as important to their character as the jobs they don’t, and the whole piece really works beautifully to bridge the earlier material with the classic ones. It even serves to introduce Sheelba and Ninguable.

Howard: Interestingly enough, Robin Wayne Bailey wrote a novel set during Fafrhd and the Gray Mouser’s wanderings, and there was at least one other story planned. Unlike so many other pastiche books, Leiber was actually involved in discussing the story and officially handed off the baton. I’ve yet to look into the book, though (Swords Against the Shadowland).

Bill: I’m curious about it too, but have not read it or even heard much about it.

Howard: Next week we start with the good stuff. “The Jewels in the Forest,” aka “Two Sought Adventure” was first published in 1939 My recollection is that it’s one of the simpler Fafhrd and Gray Mouser stories, which makes sense, seeing as how it appears to be one of the earliest. See you here!

March 16, 2015

On Conan and Writing

Following on a great post by Fletcher Vredenburgh about Karl Edward Wagner’s Bran Mak Morn novel (over at Black Gate), I decided to update my own post on Conan pastiche. I’ve read, or tried to read, a lot more imitation Conan since I wrote the document and thought it high time to update the thing.

Following on a great post by Fletcher Vredenburgh about Karl Edward Wagner’s Bran Mak Morn novel (over at Black Gate), I decided to update my own post on Conan pastiche. I’ve read, or tried to read, a lot more imitation Conan since I wrote the document and thought it high time to update the thing.

My own writing proceeds apace. Onward and upward. It looks like final changes are finished on my next Pathfinder novel, coming this fall (through Tor!).

I’m not sure when For the Killing of Kings will be released through Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s, but it’s looking more and more like it will be this coming winter. First, though, I have to finish this revision. I’m shooting to have that draft complete by the end of April. On a long trip recently I started reworking the outline for the second book and am so excited with it I’m having to restrain myself from jumping into work on it right now.

March 13, 2015

Swords Against Death Re-Read: Introduction

In the coming weeks Bill Ward and I are going to re-read a book from Fritz Leibers famous Lankhmar stories, Swords Against Death. We hope you’ll pick up a copy and join us. This week, so that you’ll have a little time to get on board, we’re just providing an overview.

In the coming weeks Bill Ward and I are going to re-read a book from Fritz Leibers famous Lankhmar stories, Swords Against Death. We hope you’ll pick up a copy and join us. This week, so that you’ll have a little time to get on board, we’re just providing an overview.

Howard: Mid-way through junior high I’d read a whole lot of science fiction but very few fantasy books and no sword-and-sorcery. I’d been playing a whole lot of Dungeons & Dragons, though, and one day I read the famed Appendix R and decided to explore its recommended fantasy reading.

Unfortunately, when I went to the library it proved woefully empty of nearly everything on the list. The used bookstore ended up being my salvation, although, owing to chance, all they had that first day was one Fritz Leiber book, which meant I didn’t actually read Robert E. Howard — sword-and-sorcery’s originator — until I was well into my twenties.

Bill: This closely parallels my own experience, and it was D&D that introduced me to Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser long before I ever read any of their stories. Books were just hard to find, even if you knew what you were looking for. I didn’t get to Conan until I was thirty, and Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser sometime after that! My luck was to find Elric in my late teens and early twenties, probably because they were all being reprinted and the old Daws also seemed easy to find at the only used bookstore I knew about at the time.

Howard: My used bookstore had a treasure trove of Moorcock, although again, because of their selection I ended up reading more obscure material first. I remain quite fond of the first Corum trilogy despite its repetition, probably because I first read it upon my initial exploration of fantasy books.

Howard: My used bookstore had a treasure trove of Moorcock, although again, because of their selection I ended up reading more obscure material first. I remain quite fond of the first Corum trilogy despite its repetition, probably because I first read it upon my initial exploration of fantasy books.

Bill: I loved both Corums. I think I read through nearly all the Moorcock S&S in my twenties and those were among my favorites, even more than Elric. As far as reading obscure material first, the first Howard I ever read were his historicals.

Howard: I love the Robert E. Howard historicals as much as his very best fantasy stories. My first purchase, though, was Swords Against Death, the most consistently excellent of all Fritz Leiber’s Lankhmar books. Chronologically for the characters it’s not the first, but it does contain many of the stories Leiber wrote first. I discovered while reading through the series that I vastly preferred the stories he wrote earlier in his life, even over the Hugo award winning “Ill Met in Lankhmar” that appeared in Swords and Deviltry. I found “Ill Met” only mildly engaging, and the rest of that volume rather weak. I always try to warn newcomers to Lankhmar that they should start with Swords Against Death.

Bill: Agree completely. When I settled down to read F&GM for the first time it was straight through in “career” order, though I’d read a few stories here and there in anthologies previously, and the first two introductory stories in Swords and Deviltry were not at all what I was expecting. The pace seemed much too languid. It wasn’t until the later books and earlier stories that I really got on board.

Bill: Agree completely. When I settled down to read F&GM for the first time it was straight through in “career” order, though I’d read a few stories here and there in anthologies previously, and the first two introductory stories in Swords and Deviltry were not at all what I was expecting. The pace seemed much too languid. It wasn’t until the later books and earlier stories that I really got on board.

Leiber wrote a lot of different sorts of things and his style shifted to reflect that — I wonder how I’d react to those later F&GM pieces now that I’ve read more widely in Leiber’s backcatalog. I suspect they’d still compare a little unfavorably to classics like “The Bazaar of the Bizarre.”

Howard: Are there other collections you like as well? I like Swords Against Wizardry almost as well as Swords Against Death. I enjoy about half of the stories from Swords In the Mist, and all of the novel Swords of Lankhmar.

Swords Against Death, though, was the one I revisited the most. Once I got past the short, storyless opening (“The Circle Curse”) I was engrossed. Every short story was approximately the same length, and a few were tangentially connected. It was a little like episodic television.

More importantly, it was exciting, fast-paced, brimming with magic and sword-play and horror and mystery — and beautiful women, a subject that was becoming increasingly interesting to teenaged Howard. I loved Swords Against Death so much that I read it at least six times in the next few years (oh, to have so much spare time and energy).

More importantly, it was exciting, fast-paced, brimming with magic and sword-play and horror and mystery — and beautiful women, a subject that was becoming increasingly interesting to teenaged Howard. I loved Swords Against Death so much that I read it at least six times in the next few years (oh, to have so much spare time and energy).

Swords Against Death was not only one of the first fantasy books I read, it was my introduction to true sword-and-sorcery. These days the line between sword-and-sorcery is a lot more blurred than it was in the mid ’70s. Back then you pretty much had high fantasy, or sword-and-sorcery, and I definitely preferred the latter for the grit and the kind of protagonists, not to mention the pacing.

Bill: It’s great that SAD was such a significant book in your life. Here obviously is where our perspectives will differ, since the “stakes” of a reread are much higher for you, now. I read SAD maybe around eight years ago when I was reading the whole series and, for me, it’s sort of hard to separate out the individual books in the series from one another. Not only did I read them all at once, but I read the book club omnibus editions. I’m looking forward to getting a sense of SAD more as it’s own book with this reread.

Howard: It’s been more than a quarter century since I last read the book, and I’m a little leery about what I’ll find. I know that the pacing will still be excellent and I have complete faith in Fritz Leiber as a prose stylist. But will I still find them some of the best adventure stories I’ve ever read? I mean, I’ve read a LOT of adventure stories after first being introduced to these. And what will I think of the way the women are handled? I was a young man in the ‘70s when I read these. Unconscious sexism was rampant then, and the majority of these tales were written even earlier, between the early ‘40s and the early ‘60s. I’m pretty sure that I’ll find a whole lot of women interacting with our protagonists as rewards rather than people. Not that I’d blame Leiber for that, if it’s what I find. Very few people can be socially ahead of their time.

Howard: It’s been more than a quarter century since I last read the book, and I’m a little leery about what I’ll find. I know that the pacing will still be excellent and I have complete faith in Fritz Leiber as a prose stylist. But will I still find them some of the best adventure stories I’ve ever read? I mean, I’ve read a LOT of adventure stories after first being introduced to these. And what will I think of the way the women are handled? I was a young man in the ‘70s when I read these. Unconscious sexism was rampant then, and the majority of these tales were written even earlier, between the early ‘40s and the early ‘60s. I’m pretty sure that I’ll find a whole lot of women interacting with our protagonists as rewards rather than people. Not that I’d blame Leiber for that, if it’s what I find. Very few people can be socially ahead of their time.

Bill: As you say, very few people can be socially ahead of their time. Since I’m not one of them, I don’t foresee the sexual attitudes of my grandparent’s generation bothering me one bit — honestly it’s refreshing to read anything that hasn’t gone through the PC blandometer of the twenty-first century.

Howard: That’s the right attitude to read this older fiction with. A lot of people wander into it without being prepared, though – they expect everything to read as though it were written in the present and aren’t willing to consider the time and circumstances under which a work was written. I always wonder how I can warn them that a work has to be considered under different parameters without sounding like I’m apologizing. Now that my daughter’s a teenager I look at my bookshelves and feel like I have to explain the worth of a lot of the old fiction I grew up with. It feels a little like having to explain why a joke is funny, which always ruins the joke.

Howard: That’s the right attitude to read this older fiction with. A lot of people wander into it without being prepared, though – they expect everything to read as though it were written in the present and aren’t willing to consider the time and circumstances under which a work was written. I always wonder how I can warn them that a work has to be considered under different parameters without sounding like I’m apologizing. Now that my daughter’s a teenager I look at my bookshelves and feel like I have to explain the worth of a lot of the old fiction I grew up with. It feels a little like having to explain why a joke is funny, which always ruins the joke.

Bill: Well, that’s one thing I tend to forget. I get frustrated when people aren’t automatically like me in how they approach fiction, aware and accepting of the context. When I hear someone, to bring a particularly egregious example, lambasting an author for a character’s point of view, I tend to wonder how these readers ever made it past their Dick and Jane.

And here I think is a point where at last, despite what our Dunsany reviews might imply, we can show that you and I aren’t actually twins linked by telepathy. Because, while we have very similar tastes, the emotional context for us is different. I have no children, and just the notion you raise about explaining to your daughter what that wall of books represents to you gives me a bit of pause. I’ve never had to so much as consider that, and it does change things. It’s very easy as a self-contained entity to just say “leave my fiction the hell alone,” but the real, constructive, thing to do is to explain to someone with a completely different perspective just what’s so great about stories that may contain a few rough edges from their contemporary point of view.

As far as Leiber goes, though, I certainly don’t think there’s anything in there as dated as, say, Nick and Nora Charles’s alcoholic banter in The Thin Man, which would be roughly contemporary with these stories. That may be one of the great advantages of fantasy fiction — the ‘no when’ of fantasy gives us a world that doesn’t date so badly and, even if there are some assumptions present that we no longer hold, well, don’t we assume going into it that a fantasy world is going to be different from our own?

As far as Leiber goes, though, I certainly don’t think there’s anything in there as dated as, say, Nick and Nora Charles’s alcoholic banter in The Thin Man, which would be roughly contemporary with these stories. That may be one of the great advantages of fantasy fiction — the ‘no when’ of fantasy gives us a world that doesn’t date so badly and, even if there are some assumptions present that we no longer hold, well, don’t we assume going into it that a fantasy world is going to be different from our own?

Howard: A fair question and challenge. I think we could keep talking about perceptions for pages to come. We should probably leave some of that for the coming weeks.

Next week I hope you’ll join us for the first story in Swords Against Death, “The Circle Curse.” Don’t despair if it leaves you a little unsatisfied. If my memory’s correct, it’s the least interesting tale in the entire volume.

March 9, 2015

Link Man!

It’s Link Man!

What with tax time approaching and me being super busy with writing, this Monday I’m just going to share some interesting links I’ve accumulated.

First up is a rather harrowing look at the terrible destruction waged by those fools from ISIS. It’s not enough that they’re killing anyone who doesn’t practice religion exactly like them. No, these tools are obliterating history because it portrays gods that haven’t been worshipped in thousands of years.

I’ve never visited Mosul in person, but in preparation for my Dabir and Asim stories and novels I’ve researched it in depth, and I feel strangely close to it as a result. I’ve been horrified to hear about the carnage carried out as ISIS has destroyed “idolatrous” statues in the Mosul museum. Now they’ve moved against the ruins of another ancient city. Because nothing’s more dangerous to your religious opinion than a bunch of old stone statues sitting in a desert. I hope some fall on them. Anyway, here’s the link.

Here’s a great essay from Ursula K. LeGuin that you might have already seen, skewering a literary writer tackling fantasy who’s desperate to prove he’s above such terrible practices.

Here’s a great essay from Ursula K. LeGuin that you might have already seen, skewering a literary writer tackling fantasy who’s desperate to prove he’s above such terrible practices.

Lastly, Scott Dennis Parker looks at one of my favorite book sets. I must have read the Star Trek Log series three or four times when I was a kid. Alan Dean Foster wrote short stories (and, later, novels) based upon the episodes in the Star Trek animated series, and somehow he made even the weakest of them compelling while being true to the scripts. It was a phenomenal job, and I had the pleasure of say as much to Mr. Foster in person at a World Fantasy Convention three or four years ago. He was very gracious. If you’ll permit me to get technical for a moment, one of the things I liked about them, in addition to him knowing the Star Trek characters better than almost anyone else who’s ever written prose about them, is that he so ably switches back and forth between characters over the course of a scene.

These days that’s called “head hopping” and is actively discouraged. Used to, though, you didn’t have to switch chapters or put in a scene break when you traded point-of-views. Done well, trading viewpoints can be extremely effective (it’s quite cinematic), yet it’s so unpopular today it has become something of a lost art. I’ve experimented with it myself but have always had it editorially nixed. And, honestly, because I haven’t had the opportunity to practice it very much I wasn’t very good at it.

March 6, 2015

Lord Dunsany’s Time and the Gods: Conclusion

Bill Ward and I finished the last four stories in Lord Dunsany’s Time and the Gods last week, and we’re taking a final look at the collection today.

Bill Ward and I finished the last four stories in Lord Dunsany’s Time and the Gods last week, and we’re taking a final look at the collection today.

Howard: Looking through our reviews I find that our opinions were almost always in accord about the stories, although there were a few differences earlier on. I wonder if that’s because the stories in the second half tended to be either exceptional or simply sort of “meh.” Likely, one of the reasons we’re friends is that we have similar tastes.

Bill: I think that’s exactly it, the stories in the second half contained the weaker pieces, although looking back at some of my notes a few of the stories may have grown on me a bit. The Dunsany fatigue was setting in for both of us — we’ve being reading and writing about him for months now — just as we started the weaker second half of a tightly themed anthology.

That of course is one of the perils of having a strong style and theme, the lack of variety made things feel a bit monotonous, though this is monotony punctuated by beauty and brilliance. I suspect our reactions to some of these stories would be (and will be) much improved under a different context. Dunsany’s rich style is a wonderful break from a cleaner or more straightforward style that characterizes the majority of fiction, but the flip side of that is it isn’t something you’d want a steady diet of necessarily, just as one doesn’t want to eat cheesecake for dinner every night.

That of course is one of the perils of having a strong style and theme, the lack of variety made things feel a bit monotonous, though this is monotony punctuated by beauty and brilliance. I suspect our reactions to some of these stories would be (and will be) much improved under a different context. Dunsany’s rich style is a wonderful break from a cleaner or more straightforward style that characterizes the majority of fiction, but the flip side of that is it isn’t something you’d want a steady diet of necessarily, just as one doesn’t want to eat cheesecake for dinner every night.

Howard: That’s fairly said. It’s just SO rich. I think the lack of characters who were more than archetypes began to wear on me. I have the same issue when I’m reading too many tales from the Arabian Nights or the Shahnameh in a row. No matter how much I enjoy the mythic aspects or lovely prose I have to go read something else or I begin to weary of the text and miss things. I’m afraid that by the time I reached the end of the collection I was more interested in finishing it than analyzing it.

Bill: I hate dwelling on this, and I suspect you do as well. I think, for both of us, our Dunsany fatigue came as a shock, which is why we’ve spent so many words trying to analyze it. A lot of words, too, to explain that, even though we got a bit tired of it, we both recognize Dunsany as a giant among giants. Even at his “worst,” he’s good. At his best, he’s in a class by himself. I think it says a lot about an author that you can get burned out on him and still look forward to reading him again — I’ll be reading and rereading him for the rest of my life. I just won’t be doing it every week for the rest of my life!

Bill: I hate dwelling on this, and I suspect you do as well. I think, for both of us, our Dunsany fatigue came as a shock, which is why we’ve spent so many words trying to analyze it. A lot of words, too, to explain that, even though we got a bit tired of it, we both recognize Dunsany as a giant among giants. Even at his “worst,” he’s good. At his best, he’s in a class by himself. I think it says a lot about an author that you can get burned out on him and still look forward to reading him again — I’ll be reading and rereading him for the rest of my life. I just won’t be doing it every week for the rest of my life!

Howard: Right on. I do want to return, but probably one collection at a time is the way to go.

Bill: On the collection itself — I was never sure, early on, if Dunsany was aiming for a cohesive universe, or taking each story as it came. Much of modern fantasy, of course, is very much concerned with the act of world building, the secondary world act of creation. For a generation of writers and readers raised on media properties, RPG sourcebooks, and Tolkien clones, the idea that you need to have that big, consistent world is unquestioned and virtually sacrosanct. I think, in some cases, all this earnest world building has the undesired and paradoxical effect of making a story seem less real, perhaps by drawing too much attention to itself as an artifact of the creator. Many of these over-engineered worlds end up fencing themselves in by their need to spell everything out, and achieve the opposite of their intentions.

Lord Dunsany inspired art by Sidney Sime.

But Time and the Gods is all over the place in that respect, containing both reoccurring characters and connected narratives, and then much that is either unique to one story only or, in some cases, inconsistencies between stories. I certainly didn’t take careful enough notes to really pick up on and systematize those inconsistencies, if that’s even possible, but I got the gist enough to assume they were deliberate. Deliberate and, as it turns out, highly effective in terms of Dunsay’s theme — in the vast ocean of time, in the history of mankind and its myriad faiths, there can be no real consistency, no cozily built world where a stranger can pick up the rules quickly and then always feel that they know where they stand. In Time and the Gods, I had no idea what was around the next corner, and it felt so much closer to reading the true accumulated myths of the past than much of the modern stuff so clearly written by those who never got much past Gygax and Tolkien.

I suspect also that the King James Bible, clearly a major influence on Dunsany’s style in these stories, probably also provided some notion, unconscious or otherwise, as to how all these tales could coexist with one another in the face of internal contradictions. I’ve heard it suggested that the great works of religion may in fact be more powerful because of things like logical inconsistencies — that these encourage a person’s suspension of their critical mind, creating an even stronger emotional belief in so doing. This is a very close parallel to the fantasy writer’s goal to have his audience suspend disbelief.

Deliberate or not, I think it’s a sure sign of Dunsany’s genius that he can tread the line between this kind of internal consistency and inconsistency. Perhaps it is completely accidental, but I really don’t think so. I think if Dunsany had cared nothing for being consistent, we would have seen many more contradictions that the collection would feel more like a mish mash. Ironically, its Dunsany’s theme and style that really serve to increase the sense of a cohesive, consistent world, moreso than the amorphous setting and distant, archetypal characters of Pegana do — but, nonetheless, there are gods, men, concepts, and names shared between these stories. The entire approach makes the world feel bigger than it is, mysterious and unpredictable. The rules can literally change from story to story, but somehow it all feels of a piece, an organic whole.

Deliberate or not, I think it’s a sure sign of Dunsany’s genius that he can tread the line between this kind of internal consistency and inconsistency. Perhaps it is completely accidental, but I really don’t think so. I think if Dunsany had cared nothing for being consistent, we would have seen many more contradictions that the collection would feel more like a mish mash. Ironically, its Dunsany’s theme and style that really serve to increase the sense of a cohesive, consistent world, moreso than the amorphous setting and distant, archetypal characters of Pegana do — but, nonetheless, there are gods, men, concepts, and names shared between these stories. The entire approach makes the world feel bigger than it is, mysterious and unpredictable. The rules can literally change from story to story, but somehow it all feels of a piece, an organic whole.

I am curious, going forward (eventually), and reading other tales set in Pegana, to see if and how the consistent and the inconsistent play a hand. Howard, as someone that has read more Dunsany than me, would you say more of these consistent, shared characters or places appear in other Pegana stories?

I am curious, going forward (eventually), and reading other tales set in Pegana, to see if and how the consistent and the inconsistent play a hand. Howard, as someone that has read more Dunsany than me, would you say more of these consistent, shared characters or places appear in other Pegana stories?

Howard: It’s more that they’re part of a consistent style, with occasional references to places or gods that he’s mentioned before. Someone, somewhere, has probably cross-indexed all this stuff, but I have to rely on my memory, and I still haven’t read all of Lord Dunsany’s work. As a matter of fact, I still haven’t made it all the way through the first of Lord Dunsany’s books, The Gods of Pegana. It has an even stronger “Old Testament” feel than the stuff we’ve read here, although it deals with multiple gods instead of one. I honestly found it a little hard going, moreso than Time and the Gods, although it’s been too long since I’ve read it to remember details. The six-book omnibus I picked up places it last even though it was the first written chronologically, perhaps in recognition of some more challenging prose.

As far as this collection, my favorites remain “The Coming of the Sea,” “The Vengeance of Men,” “The Cave of Kai,” “Night and Morning,” “The South Wind,” and, of course, “The Journey of the King.” I’ve only changed opinions on one of hem, and that’s my elevation of “The South Wind” over some of the runner-ups, which I list below. Something about “The South Wind” really stuck with me, even though I originally only awarded it one star.

As far as this collection, my favorites remain “The Coming of the Sea,” “The Vengeance of Men,” “The Cave of Kai,” “Night and Morning,” “The South Wind,” and, of course, “The Journey of the King.” I’ve only changed opinions on one of hem, and that’s my elevation of “The South Wind” over some of the runner-ups, which I list below. Something about “The South Wind” really stuck with me, even though I originally only awarded it one star.

Runner ups were “A Legend of the Dawn,” “When the Gods Slept,” “The Sorrow of Search,” and “Usury.” That’s ten in all that I will at least revisit and six I would certainly include in a best-of collection. Despite our Dunsany fatigue, that’s a fair half of the book, more, really, given the length of “The Journey of the King.”

How do you divide your favorites and nearly so?

Lord Dunsany

Bill: My choices are very similar to yours Howard, as usually seems to be the case. My favorites were “The Coming of the Sea,” “A Legend of the Dawn,” “The Cave of Kai,” “The Sorrow of Search,” and “The Journey of the King.” I’ve improved my already favorable opinion of ‘The Sorrow of Search” as I feel like it’s really stuck with me.

Runners up for me were “The Vengeance of Men,” “The South Wind” “The Men of Yarnith,” and the short and sweet duo of “Usuary,” and “Mlideen.” I’d say in retrospect most stories have gained in my estimation at least a bit, I suspect because, looking back over my notes, most of them do have something very memorable about them, an image, a scene, a metaphor.

My absolute favorite stories tended to be the ones that really explored the potential of the extended mythic metaphor: the remaking of the primordial landscape in “The Coming of the Sea,” the day-night cycle as fuel for a creation myth in “A Legend of the Dawn,” and the small victory against the loss of human experiences to the ravages of time in “The Cave of Kai.”

Overall, despite a few weak pieces, Time and the Gods was another great collection, the stand out stories here are as good as anything I’ve read by Dunsany. His great themes of time and loss, his bottomless well of invention, and his unique voice all serve to make these stories really feel like ‘typical’ Dunsany stories — these kinds of tales are exactly what I think of when I think of Lord Dunsany, and it seems to me he was born to write them.

Overall, despite a few weak pieces, Time and the Gods was another great collection, the stand out stories here are as good as anything I’ve read by Dunsany. His great themes of time and loss, his bottomless well of invention, and his unique voice all serve to make these stories really feel like ‘typical’ Dunsany stories — these kinds of tales are exactly what I think of when I think of Lord Dunsany, and it seems to me he was born to write them.I have to say I am looking forward to revisiting some of the Dunsany I read years ago and reevaluating it in the light of all the Dunsany we’ve just read, which has really served as an education for me. After a bit of a break, that is.

Howard: All excellent points. I happen to think that the mythic stories were the most enjoyable as well, and we’re not alone. They tend to turn up in most of the “best of” collections I’ve seen.

Alright, that’s it for Lord Dunsany for a while. Next week we’ll start on Swords Against Death by Fritz Leiber.

March 5, 2015

Farewell

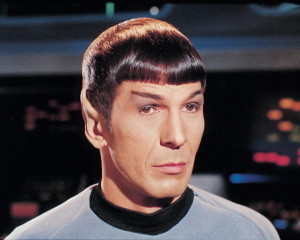

I’ve debated even tackling this subject. There have been numerous moving tributes to Leonard Nimoy already, including an excellent one penned by Thomas Parker over at Black Gate. Then there’s the fact I never knew Leonard Nimoy and I feel a little silly commenting upon the death of a celebrity.

I’ve debated even tackling this subject. There have been numerous moving tributes to Leonard Nimoy already, including an excellent one penned by Thomas Parker over at Black Gate. Then there’s the fact I never knew Leonard Nimoy and I feel a little silly commenting upon the death of a celebrity.

But when I take into account how much the original Star Trek meant to me when I was a boy and a young man and how fond of it I remain, and when I consider how much impact Star Trek had upon my moral development, I think pausing for a moment with bowed head is more than justified.

Gene Roddenberry, Star Trek’s creator, called Leonard Nimoy the conscience of Star Trek, and there’s much to be said for that. Anyone who’s enough of a Trekker to have read the behind-the-scenes stuff like me knows how instrumental Nimoy was in inventing Vulcan society and culture and knows how he strove, even amid the mostly dreadful third season of scripts, to keep Spock logical and consistent.

Gene Roddenberry, Star Trek’s creator, called Leonard Nimoy the conscience of Star Trek, and there’s much to be said for that. Anyone who’s enough of a Trekker to have read the behind-the-scenes stuff like me knows how instrumental Nimoy was in inventing Vulcan society and culture and knows how he strove, even amid the mostly dreadful third season of scripts, to keep Spock logical and consistent.

I read a number of remembrances and appreciations of Mr. Nimoy in the days following his death, and the majority of writers said Spock was their favorite character because they could relate best to him. That wasn’t me. I knew I could never be Spock. I thought I could emulate Kirk. Not because of the womanizing, which is actually rare in the good episodes, but because of his leadership style. He was clever, resourceful, compassionate. He put his friends and his duty first. And one of those friends, perhaps his best friend, was Mr. Spock. If I could never imagine actually BEING Spock, I longed to have a friend like him who was loyal, dependable, and brilliant.

Nimoy did many other things besides being Spock. He led a long, successful life, which is probably why I didn’t end up mourning him as much as I’d expected. And perhaps, as my wife has said, I knew that his work lives on. Neither she nor I mean that Spock lives on because of the new movies, which really don’t get Star Trek or its characters, but because of the original show and, to a lesser extent, the movies with the original cast. Nimoy’s dedication is there for all to see.

Nimoy did many other things besides being Spock. He led a long, successful life, which is probably why I didn’t end up mourning him as much as I’d expected. And perhaps, as my wife has said, I knew that his work lives on. Neither she nor I mean that Spock lives on because of the new movies, which really don’t get Star Trek or its characters, but because of the original show and, to a lesser extent, the movies with the original cast. Nimoy’s dedication is there for all to see.

Later generations already don’t understand the budgetary limitations of Star Trek — they find the effects campy, as though it was deliberately cheesy, when at the time it was the best that could be done. They don’t understand that Trek was frequently producing a script that had JUST been written and possibly hadn’t been perfected before it was time to shoot. And many today certainly don’t get how far advanced Trek was in so many ways that we now take for granted — no characters who smoked, women department heads, different races co-existing peacefully, etc. Even those mini-skirts were seen by the women who wore them on the show as liberating rather than sexist.

We can’t expect new generations to understand our touchstones. Or, at least, we shouldn’t. But I can hope that the actors who inspire my children have the same commitment and integrity as those who inspired me. To Leonard Nimoy, those weren’t just lines on the page. He insisted that some scenes be rewritten or even added, not, as some actors might, because he wanted more limelight, but because he wanted his character consistent, intelligent, deductive. And human, odd as that sounds. Those who aren’t fans probably don’t understand that beneath that cold exterior Mr. Spock was fiercely loving and protective. It was Nimoy’s gift to portray that subtly, usually by inches.

We can’t expect new generations to understand our touchstones. Or, at least, we shouldn’t. But I can hope that the actors who inspire my children have the same commitment and integrity as those who inspired me. To Leonard Nimoy, those weren’t just lines on the page. He insisted that some scenes be rewritten or even added, not, as some actors might, because he wanted more limelight, but because he wanted his character consistent, intelligent, deductive. And human, odd as that sounds. Those who aren’t fans probably don’t understand that beneath that cold exterior Mr. Spock was fiercely loving and protective. It was Nimoy’s gift to portray that subtly, usually by inches.

Leonard Nimoy was a key component in Trek’s vision of a far future, one full of talented, intelligent, devoted people. Millions of people know his name, and hundreds of thousands, at least, from all walks of life, respect and appreciate his work as Mr. Spock. He inspired us, and we are grateful to him. I can imagine what Star Trek would have been like without him, but I don’t really want to do so. Gene Roddenberry chose the right Vulcan for the job and we are all better for it.

I extend my condolences to his friends and family. Had I ever had the chance to do so, I would have joined the long line of people who thanked Mr. Nimoy for his hard work and commitment to the role that he embraced so fully. And now, because I can no longer wish him a long and prosperous life, I shall say Hail, and Farewell.

March 2, 2015

Hard Boiled Monday: You Play the Black and the Red Comes Up

As with preceding Hardboiled Mondays, Chris Hocking and I are working our way down the master list in alphabetical order. Details and the list are here. And earlier discussions are here.

As with preceding Hardboiled Mondays, Chris Hocking and I are working our way down the master list in alphabetical order. Details and the list are here. And earlier discussions are here.

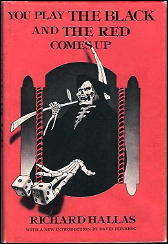

Today Chris and I are looking at a remarkable novel by Richard Hallas writing under the pseudonym Eric Knight titled You Play the Black & the Red Comes Up.

Chris: Repeated readings have deepened the often conflicting impressions this novel makes upon me. It was written under the Hallas pseudonym by Eric Knight, an Englishman who would pen the romantic bestseller, This Above All and the kid’s classic Lassie Come Home before dying in a plane crash over Surinam during the Second World War.

Chris: Repeated readings have deepened the often conflicting impressions this novel makes upon me. It was written under the Hallas pseudonym by Eric Knight, an Englishman who would pen the romantic bestseller, This Above All and the kid’s classic Lassie Come Home before dying in a plane crash over Surinam during the Second World War.

The book was apparently a minor bestseller in 1938, though after its initial hardcover appearance it had to wait until the 1950s to appear in paperback as a neat little Dell mapback. Then it waited thirty-odd more years for the noble, lamented Black Lizard Press to bring it briefly back into print. I’m pleased to say that it’s available today from Pharos Editions with an introduction by, of all people, Matt Groening.

It’s tough to make a solid evaluation of this book. It’s something of a pastiche of the American hardboiled novel of the ’20s and ’30s. It’s part James M. Cain, part Ernest Hemingway, part pulp crime novel, at times self-mocking farce and at others surreally sincere.

It’s tough to make a solid evaluation of this book. It’s something of a pastiche of the American hardboiled novel of the ’20s and ’30s. It’s part James M. Cain, part Ernest Hemingway, part pulp crime novel, at times self-mocking farce and at others surreally sincere.

Hallas mocks some of the characters he depicts, making them shallow, goofy, drunken, and self-absorbed. At times he seems to mock the terse, blunt prose style he affects. Sometimes this is funny, and sometimes it isn’t.

This unevenness of tone may have been more or less apparent when the book was new, but I think the novel’s highlights, its virtues, must have been as obvious then as they are now.

There is murder, duplicity and a searing look at Hollywood featuring what is probably the first mad movie director in fiction. There’s a frame and a trial and a sense of justice twisted beyond any recognition.

And then there’s the narrator, a tough, forthright young man whose essential simple-mindedness imposes no limit on the depth of his feelings, or on his need to understand. The bluntness of his style is at times played for laughs, but there are plenty of instances where his words have a compelling honesty and even a rough beauty. The dialogue is excellent and used to lift a number of scenes to heights beyond what most anyone would expect of the novel.

And then there’s the narrator, a tough, forthright young man whose essential simple-mindedness imposes no limit on the depth of his feelings, or on his need to understand. The bluntness of his style is at times played for laughs, but there are plenty of instances where his words have a compelling honesty and even a rough beauty. The dialogue is excellent and used to lift a number of scenes to heights beyond what most anyone would expect of the novel.

There is a sequence in which the narrator is playfully urged by his lover to explain how he feels about her, to compare his love to other things he values. His determinedly relentless catalog of the things his love is like is both humorous and wrenching. Anyone who has ever groped for words when they were needed most will understand. There are a number of scenes which display the narrator’s emotions in a powerful, subdued fashion, the voice of one who speaks little, and has small faith in words.

The conclusion is surreal , enigmatic, moving, and has generated some debate down the years. I’ll say no more about it except that it haunts me.

It occurs to me that I’ve read this book at least four times and that I’ve picked it up to find and re-read specific scenes more times than I can tell. This is one of the very few books that I return to over and over, especially when life becomes difficult. I’m not entirely sure why, but I am sure that I would not be without it.

Howard: Chris describes the novel’s strengths, weaknesses, and overall tone so eloquently that there’s very little for me to add.

This was a beautiful and moving book. If it didn’t touch me nearly as deeply as it has Chris, that’s probably because I’ve discovered while reading the entries on this list that I prefer hardboiled stories to noir. This novel is Bleak (note the capital) and powerful and haunting, but I’m not sure it’s one I’m eager to revisit.

On the other hand, I’m keeping my copy of You Play the Black and the Red Comes Up, which is certainly a mark of respect. I don’t bother holding on to books I don’t plan to re-read any more.

Howard Andrew Jones's Blog

- Howard Andrew Jones's profile

- 368 followers