Winn Collier's Blog, page 32

April 8, 2013

Prayer and Play. And Treehouses.

Two Christmases ago, Miska gave me a splendid coffee table book, New Treehouses of the World. I have never owned a treehouse, but my cousin Tim and a few of his pals built a magnificent tree fort that I envied as a child. Tim was a few years ahead of me, and the fort was in disrepair by the time I was old enough to have enjoyed it. However, in seminary, I stayed with my aunt and uncle several nights a week, and each day on my way home from class, I’d pass that rotted-out beauty and pine for what might have been.

Two Christmases ago, Miska gave me a splendid coffee table book, New Treehouses of the World. I have never owned a treehouse, but my cousin Tim and a few of his pals built a magnificent tree fort that I envied as a child. Tim was a few years ahead of me, and the fort was in disrepair by the time I was old enough to have enjoyed it. However, in seminary, I stayed with my aunt and uncle several nights a week, and each day on my way home from class, I’d pass that rotted-out beauty and pine for what might have been.

The book sat on my dresser for an entire year unopened until last December when I was packing for two days at Holy Cross Abbey, a Trappist monastery where I planned to retreat. I was exhausted and in much need of a spiritual infusion. On a whim, I tossed the bulky Treehouses into my backpack. I had not opened the book in the entire year prior, and this beefy hardback was not the sort of book you take on travels. Nor was it the sort of spiritual tome one would normally consider part of the reading list during days with the Trappists. Yet there it was in my North Face pack, and I couldn’t possibly tell you why.

On the drive north, I began to think of what God might have for me during my time, and the word that repeatedly returned to me was play. This was not the word I would have picked, which is at least half a reason for thinking it’s something to pay attention to.

I pulled into the parking space for the retreat house, aware that the crisp air and the tree’s brittle branches matched the tone of my soul. When I stretched out of the car, an old, very fuzzy grey cat slowly strolled my way. The cat, acting as guestmaster, purred a hello, turned to point me toward the front entrance and then, having done his duty, slowly patted away. I’m not one to pause for a cat, but I stood there for a moment chuckling. The greeting struck me as magnificently playful.

That evening, I laid on the twin bed in my monastic cell; and though I had planned to spend time in focused, contemplative prayer, my brain had all the perkiness of cold molasses syrup. I opened a book of Thomas Merton’s spiritual letters to read, followed by a volume of poetry and a couple theological works. I thumbed several pages of each, but they all made me weary. What the heck, I thought. I pulled out the treehouse book and into the wee hours of the night, I gobbled up pictures of play spaces from around the world. I remembered my boyhood fantasies and my love of rugged spaces. I considered what it would be like to craft one of these tree abodes, hopefully building it with my sons. In that little cell, I played.

St. Gregory of Nazianzus, that theologically prolific fourth-century bishop, reminded us that “man is the play of God.” God’s high creation, his own image, came as an act of play, of joy and delight and imagination run wild. When our theology is so serious and our discipline so stringent that we no longer have hearts at play, then we have massively missed the point. Prayer and play, these are two ways of talking about the same thing.

April 1, 2013

Weeping, Then Laughing

Lent is 40 days. Easter runs 50. This matters.

While Lent blocks the exit for those chipper souls who’ve never seen a sorrow they couldn’t deny, Easter opens the floodgates on parched souls who’ve come to believe only in a life barren and brittle.

But – and this is what we must not miss – Easter trumps Lent. Lent owns its grey space, and the good news is no good news at all if we do not sincerely wrangle with the sad facts scattered about us. But then Easter comes and flips on the sunshine and cranks up the jukebox and opens the windows and breaks out the margaritas. Death is very real, Easter says, but Jesus alive is more real. Get up and dance.

Easter does not arrive as a joy easy won. Easter is the dance of the mourner who has grabbed the alleluia in a headlock and won’t let go. In Easter, those who dwell in the valley of the shadow of death gather up their courage and bend their ear to the Church’s witness of the risen Jesus. Then, in an act both brave and costly, these reckless souls let the light in. They open themselves to another possibility. They slowly start to tap their toe. With all their might, no matter how fragile or sparse, they begin to practice joy. They begin to Easter.

I was dead, then alive.

Weeping, then laughing.

The power of love came into me,

and I became fierce like a lion,

then tender like the evening star.

― Rumi

March 31, 2013

Easter Blessing

People of the risen and conquering Jesus, lift up your weary hearts. Lift up your sorrowed eyes — your Jesus has risen from the dead. Easter’s for real. Jesus lives. And all the dying and all the deaths that lay claim on you have been crushed by the power of Jesus Christ, the one who descended into the very bowels of hell and marched out with a victor’s dance. Rise up and live. In the name of the Father and the Son and the Spirit. Amen.

March 29, 2013

Broken on Good Friday

In 1983, Eric Wolterstorff died in a tragic accident while climbing the Alps. He was 25. His father Nicholas, a theologian and philosopher from Yale, journaled his sorrow in the months that followed. Among his weary words were these:

I tried music. But why is this music all so affirmative? Has it always been like that? Perhaps then a requiem, that glorious German Requiem of Brahms. I have to turn it off. There’s too little brokenness in it. Is there no music that speaks of our terrible brokenness? That’s not what I mean. I mean: Is there no music that fits in our brokenness? The music that speaks about our brokenness is not itself broken. Is there no broken music?

If we are to walk backwards in our world and if we are to reckon with the true horrors, then we need broken music. We need brave people who are not afraid to linger in the falling-apart places. I do not mean folks who by their disposition only see the bleak, for bleak is thank goodness not at all the whole of it. I do not mean artists who use the grotesque as their shtick or politicians who use our fear of calamity to bolster their power. I mean people who know the Beauty of the world but who also know there is a wasteland in the human soul. People who know Love but who also, deep in their marrow, know how many of our nights and days are overwhelmed by sadness.

And we do not need people to pontificate all these sorrows we know full well but are unable to escape. We need brave souls who will enter with us, who will help us meet our afflictions honestly and help us grapple in the dirt. We need friends who know that we must, like Jacob, wrestle into the cold midnight with an angel or a demon – who can say which just yet?

We need musicians who will sing the song with us – and sometimes for us – that we have not yet been able to sing. We need poets who will write the costly verse, born out of their own travail, and then offer it as gift to those of in such disarray that we are unable to locate the language. We need writers who, after they have cut their skin and their soul and bled onto the page, say, “Come, I’ll walk with you for the next hard mile.” We need preachers who don’t merely give us homilies from on high but who wonder with us if the good news could be true – and then preach with the conviction of one whose very life hangs on this hope. We need the broken ones.

Of course, offering one’s broken self for the healing of another is central to the Christian narrative and to how our faith takes on flesh in every time and place. Good Friday gives us a God broken. A God shattered under a dark sky. A God with us in our bleakest place. A God spilt out as balm for our wound, as hope that points us toward Easter.

March 25, 2013

O’Connor, Holy Week and Walking Backwards

Today is Flannery O’Connor’s birthday. She would have been 88, and I would have taken great joy watching this iconoclast toss firecrackers into our modern sensibilities. Strange, isn’t it, to think O’Conner could have lived into the era of YouTube if lupus hadn’t cut her low at 39. O’Conner’s first claim to fame happened when she was six. A British newsreel company traveled to her family farm in Millsville, Georgia to capture young Flannery’s (she went by Mary then) feat: she taught a chicken to walk backwards. “I was just there to assist the chicken,” she said, “but it was the high point in my life. Everything since has been anticlimax.”

Hyperbole, of course, but O’Conner did, in so many ways, walk backwards into her world. She was a farm girl, spending much of her energies raising both barnyard poultry and exotic fowl (with particular interest in peacocks). She was Southern, which made her an oddity among the literary elite. She was Catholic, which made her an oddity among the Southern aristocracy. Yet she was a person of her place, a person of her people. She wrote the world in which she lived. When criticized for her story’s dark underbelly, O’Connor was unmoved. “The stories are hard but they are hard because there is nothing harder or less sentimental than Christian realism… when I see these stories described as horror stories I am always amused because the reviewer always has hold of the wrong horror.”

The Christian way, from its very core, is to walk backwards. In yesterday’s reading from the prophet Isaiah, the image of the bloodied Messiah offering his cheeks to those who ripped his beard would not leave me. “I did not hide my face from insult and spitting,” said the suffering Savior. God never hides from insult or spitting, from the dark nightmares of our world, from the sorrowful stories we live. God does not hide from the horror. God steps into the very middle of it.

Isn’t it strange that Christian faith has so often been used as a means to deny our bleakest realities? Isn’t it strange that some of our weakest art, our most naive fiction, our blandest passions, arrive with the label ‘Christian’ plastered upon their fragile façade? How can God heal what we will not acknowledge? How can Christ’s passion strike into the crucible of our lives if we do not own the fact that there is a powerful darkness, if we do not tell the truth of how we flail and rage but appear entirely helpless to enact any remedy? With our Christian edicts and our moral announcements, perhaps we’ve got hold of the wrong horror.

And how can the beauty we offer possibly embody our full glory and splendor if we believe our gritty, emblazoned humanness unworthy of our keen attention and our unvarnished description?

We need art that carries us into our full humanness, that won’t let us go until we do justice with the bare facts of our lives. We need stories that grapple with all of our humanness, narrating both the havoc and the luster. We need to be reminded that Easter announces our hope that ruin is not the end. There is joy. There is life. But they come through, not around, the valley of the shadow of death. And this traverse will surely seem like walking backwards.

March 22, 2013

Amy’s Letter

A day or two ago, I got caught up in a flash of inspiration. These don’t come often, and when they do, you’ve got to grab that dragon and ride, ride, ride.

What started to be one thing ended up another, and lo and behold a (very) short story came to life. It shaped up as a tale about a three-ring circus, a brave letter and a woman who calls it like she sees it. The story starts like this:

Fred and Amy were neighbors on Rural Route 28. Their mailboxes shared a weathered post at the end of the gravel lane. This seemed fitting since their families also shared a weathered pew at Zion Presbyterian Church. Fred and Amy, along with Stan the tire salesman and Robert the county’s public defender, made up Zion’s Pastoral Search Committee. Though a thankless job, their assignment did mean that every Thursday night, they’d sit in the church’s empty manse, drink Folgers and have a few minutes to shoot the shit. Then they’d return to the pile of resumes that supposedly represented the last hope for their beleaguered flock. (read on)

I wrote this for a friend, but I’ve discovered it was even more for me. This story gets at some of my deepest frustrations with the predicament we find ourselves – but also it gets at my grandest hopes for I what I mean when I use the word pastor. I’d be pleased to share it with you.

Oh – and may I add: if you have a pastor, go easy on ‘em, chances are they’re getting their teeth kicked in at least a couple times a month. And if you have a good pastor, tell ‘em so. They may not act like your gratitude matters, but I absolutely promise you that it does.

March 18, 2013

Sunday Rebellion

The calendar hanging on your refrigerator, the one tucked behind your kid’s crayola project and the magnet reminding you to “Keep Calm and Carry On,” may be the most rebellious and spiritually formative thing you own. You’ll notice how each week, right as rain, commences with Sunday. This is the day older Christians referred to as the Sabbath. A day for leisure, for church, for the Sunday paper, for the comics, for a visit on the porch with friends drinking sweet tea and swapping stories about the neighbors.

My dad told me how his mom spent chunks of Saturday cooking fried chicken, peas, rolls and chocolate cake so no cooking would be necessary on Sunday. Saturday night meant a bath out in the garage, the old wash tub filled with hot water his mom carried via multiple trips from the kitchen stove. Anything considered a chore would be done on Saturday because Sunday was a day of rest.

In the Christian tradition, Sabbath is the day our week starts. We begin with a lull. We commence, not with sweat or labor, but with loafing, with three-hour naps, with conversations feeling no need to get anywhere and enjoying long pauses and long thoughts. These Sabbath spaces possess enough quiet to pay attention to the wind and the smell of rain – and to the one sitting with you. In our Sabbath interludes, prayer happens as God intended, laced through our ordinary laughter and joy.

The Christian week begins with rest. I can’t imagine a more counter-cultural affirmation. The rhythms of our world have gotten cattywonkus. For many of us, Sunday is the day we’re cramming last bits from our to do list, capping off a week of fury and frenzy. Then, the way we see things, the week kicks off on Monday, the day we get to work, the day we recommit to serving the man and paying the bills. In this twisted narrative, the week begins with us working, not with us resting.

This is not so much about how we count our days but about how we count our lives. In a world where we yield to heavy shackles, defined by our production or our corporate rank or our Google Analytics report, it is a subversive act to shut it down and take a nap.

According to the Biblical story, however, our lives commence with respite. The Jewish day went from sundown to sundown. This meant that the Hebrews started their day by going to sleep. When they woke, fresh from a long slumber, they discovered that God had never slept. The world still turned on its axis, and the sun still shone bright. As they entered their day’s work, rested and invigorated, they were merely joining God in God’s creative activity. But only for a while, until it was again time to call it quits, crawl under the covers and let God be God. We really can cease our labors, because God’s labor holds this whole shebang together.

Of course, Advent signals the start of the Christian year. Advent, a time of waiting, a month-long Sabbath. We’re all revved and geared up for the start of things, to get the ball rolling, to turn over a new leaf. And then we wait. And wait. And wait. We’ll get to our cue, our time to punch ‘go.’ But first, we watch and slumber and drink hot chocolate with our kids. Sabbath is stitched into every rhythm of our life.

Next time you pass your fridge, linger a moment at that line of Sundays. Then linger a little longer.

March 11, 2013

An Inadequate Grace

I’m in the middle of PhD studies at the University of Virginia, a “public ivy” that trades off with UC Berkeley most years for the spot of top-ranked public university. What this means is that there are multiple times a week when I’m the dumbest person in the room. I console myself with how I’ve got life experience, often by nearly two decades, on most of my cohorts; but this additional fact only means that on top of being slow, I’m also old. I’m 41. Welcome to college.

Being in a situation where your limits and inadequacies are laid bare provides a true gift. Since I’m a writer and a father and a pastor, this position is nothing new to me. Regularly, I’m reminded of how many better writers there are, how much better their books sell. Several times, I’ve found a copy of one of my books bargain-priced in the used book store, never read. I know this because I looked. Closely. Once, I found the copy at a bookshop across the street from the church I pastored. So I’ve pieced this together – one of my own parishioners thumbed through the book, shrugged and said, “Eh, toss.” That book sat on that lonely shelf for over a year. I know this because I looked. Regularly. I was only released from that gloomy wake because we moved four hundred miles away.

Of course, I’m a dad, and most weeks I find the last few drops of my fatherly know-how circling the drain. I love those boys, but I will tell you that most of the time, I am absolutely winging it. When it comes to my pastoral life, it’s no different. There are many, many pastors who seem to have the right word and the right shine. We all like to play the part of the humble pastor, but God knows, some of us hit it on cue simply because we’re flailing about no matter when you look our way.

This isn’t to say I don’t have my stellar moments. From time to time, I’ll land a zinger of a sermon, and most days, I like the words I scratch together. While I flub regularly and have to say “I’m sorry” an awful lot, on the whole, I’m a pretty kick ass dad. I’m even learning to muck my way through a PhD.

But here’s the thing: the more we try to compensate for our weak places, the more we try to edit the “us” others encounter, the more we attempt to hide the fact that we really aren’t nearly as smart or agile or profound or intriguing as we suspect others judge us to be (or as we desire for others to judge us to be), the less we become our true selves, the less beauty we’re able to give away. Worse, as we maneuver and manipulate in all these places, we will find ourselves exhausted by our self-absorption. One of the graces Lent has brought me is this relaxing revelation: I am so tired of myself.

The world does not need perfection. It doesn’t need the best ‘you’ that you can dream up. The world needs you. The actual you. Foibles and giggles and goofiness and all. Would you be brave enough to give it to us?

March 7, 2013

Crime Scene

Unfortunately, we’ve had need for multiple forays to the pharmacy over the past few weeks. On my last two trips, I’ve happened upon a crime scene. With the first, I barely missed the burglar, and when I arrived the store clerks were all wired up about how brazen the fellow had been. Tuesday, however, I found myself right in the thick.

“Security to the office, security to the office.” An agitated voice crackled over the speaker system.

Minutes later, a woman burst out the door at the back of the store, young girl with the cutest frizzy hair in tow. The girl couldn’t have been older than six or seven, and her mom frantically drug her around the narrow store aisles calling out, “Where’s my cart? Where’s my stuff? I didn’t steal nothing. Nothing.”

Apparently protocol says that store security can question a suspect but can’t physically detain them – the police are required for that. So the woman was making her run for the parking lot before the officers arrived. Initially, when everything went down, the woman had left her purse and her daughter’s jacket in a cart, and during the brouhaha had gotten disoriented. She scurried past the shampoos and the St. Patrick’s Day candy and the Snuggies and the cough medicine in flustered circles, panting, searching furiously. “Where’s my stuff? Where’s my stuff? I didn’t steal nothing.” She brushed right past me on one of her sweeps, and there was a sadness and a terror that followed them.

She found her cart and made a beeline for the front entrance. As I left with our meds, two officers were at the front counter, taking inventory of the items security had taken from her. She’d lifted three or four bottles of perfume. The assistant manager wrapped them back in their packaging while describing the scene and the woman to the policemen.

The woman stole perfume. I don’t know her plans for the loot, perhaps something shady. But I wonder if a part of her simply wanted to feel good about herself, to wear a bit of glamour and to own a scent that would allure, to feel pretty.

Mostly, though, I wonder about the cute, frizzy-haired girl, about the fear she knew as the trouble escalated, about how she’ll remember, years from now, the day her mom drug her through the store trying to find her purse before the police came. I hope her mom held her long and tight that night. I hope her mom said, “I’m sorry, baby. That’s not who I am, that’s not who we are.”

When we talk about God making the world new, we’re talking about things like this, the sorrowful stories in our own neighborhoods. We hope and pray and work toward the good day when love and plenty and light will cover all. In that day, moms will have all they need, and daughters will have no reason to be ashamed or afraid.

March 4, 2013

Beyond the Wilderness

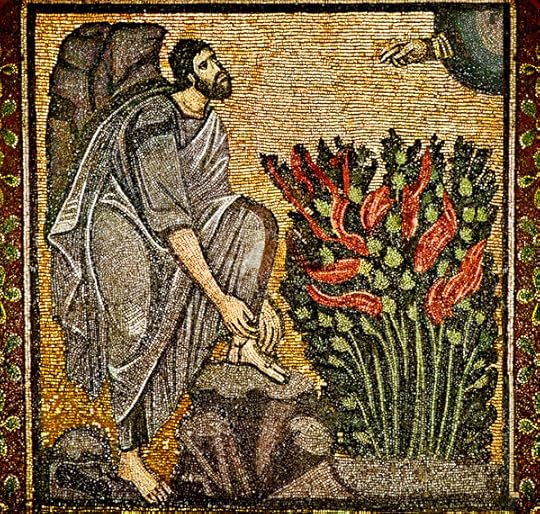

Moses ran from Egypt, ran from his family, ran from Pharaoh, ran from his past. Decades had passed, four of them. Moses was a different man now, with a wife and a family and a livelihood. Moses had run himself into an entirely different story. The hard truth, however, is that when we run from our stories – when we run from ourselves — what we find whenever we get wherever it is we’re going is simply this: we’re lost.

Moses ran from Egypt, ran from his family, ran from Pharaoh, ran from his past. Decades had passed, four of them. Moses was a different man now, with a wife and a family and a livelihood. Moses had run himself into an entirely different story. The hard truth, however, is that when we run from our stories – when we run from ourselves — what we find whenever we get wherever it is we’re going is simply this: we’re lost.

When the Exodus narrative finds Moses, the Scripture says that he’s “beyond the wilderness.” Another version says he’s made his way to the “far side of the wilderness.” As any man who refuses to stop for directions on a road trip will tell you, there’s lost … and then there’s lost. Moses is lost.

The immediate fact is that he’s taken his flock beyond the boundaries, in need of fresh grass and good water. However, this episode situates the reality of Moses’ life: the man is out in the boonies, a long, long way from home. Where are you Moses? What are you doing?

What I find most remarkable about this tale is the fact that Moses seems quite fine with the state of affairs. Moses is taking care of his family, working his flock. Moses has not ventured into the wild for a pilgrimage or a rigorous spiritual retreat. Moses is not in search of an epiphany; he has not embarked on 40 days of Lenten fasting. Moses wants grass for his sheep.

Churchy folklore suggests that God only shows up to those who are searching vigorously. If we want to hear or see God, says those who supposedly know, then we’ve got to stretch our faith and push our spiritual muscle. We’ve got to repent or fast or give up all we own. We must answer the call to get radical and be willing to head off to a third-world country at the drop of a hat. These are the elements that keep God tapping his fingers, waiting perturbed until we get serious.

But then sometimes God just shows up in a burning bush and scares the living bejeezers out of you. Sometimes, purely uninvited, God finds you in the wild corners while you’re minding your own business and simply doing the best you can to keep your head above water.

The fact is that God comes looking for everybody.