Bill Murray's Blog, page 8

December 21, 2021

100 Zimbabweans …

December 17, 2021

Among the Non-Humans

Here’s my most recent 3 Quarks Daily article published on 6 December, titled On the Road: Among the Non-Humans:

Cogito Ergo Sum? Welcome to the party. There’s a lot more going on out there than we sometimes think: Cephalopods memorize, learn, invent, and play; indeed, they acquire information about the outside world while still in their eggs. • The small, flowering thale, or mouse-ear cress, can detect the vibrations caused by caterpillars munching on it and so release oils and chemicals to repel the insects. • The fruit fly Drosophila shows evidence of depression if it gets too hot. • Plants discern the difference between blue and red light, and use this information to know which direction to grow. They differentiate between the dimming scarlet light of sunset and the brightening orange light of sunrise, to determine when to flower. • Pigs comprehend symbolic language, plan for the future and discern the intentions of others. They bore easily and show a clear preference for novelty. • When researchers arranged oat flakes in the geographical pattern of cities around Tokyo, slime mold constructed nutrient channeling tubes that closely mimicked Tokyo’s metro rail. • Some plants can feel you touching them. • Cuvier’s beaked whales can dive to 10,000 feet and stay there, at tremendous pressure, for up to two hours. In 2020 scientists recorded a Cuvier’s beaked whale staying below the water for 3 hours 42 minutes. • The nearly blind star-nosed mole, the world’s fastest eater, can find and gobble down an insect or worm in a quarter of a second. It hunts by bopping its star against the soil as quickly as possible, touching 10 or 12 different places in a single second. • The 10 centimeter long cleaner wrasse, a reef fish, has joined great apes, bottlenose dolphins, killer whales, Eurasian magpies and a particular Asian elephant in exhibiting self-awareness.

Cogito Ergo Sum? Welcome to the party. There’s a lot more going on out there than we sometimes think: Cephalopods memorize, learn, invent, and play; indeed, they acquire information about the outside world while still in their eggs. • The small, flowering thale, or mouse-ear cress, can detect the vibrations caused by caterpillars munching on it and so release oils and chemicals to repel the insects. • The fruit fly Drosophila shows evidence of depression if it gets too hot. • Plants discern the difference between blue and red light, and use this information to know which direction to grow. They differentiate between the dimming scarlet light of sunset and the brightening orange light of sunrise, to determine when to flower. • Pigs comprehend symbolic language, plan for the future and discern the intentions of others. They bore easily and show a clear preference for novelty. • When researchers arranged oat flakes in the geographical pattern of cities around Tokyo, slime mold constructed nutrient channeling tubes that closely mimicked Tokyo’s metro rail. • Some plants can feel you touching them. • Cuvier’s beaked whales can dive to 10,000 feet and stay there, at tremendous pressure, for up to two hours. In 2020 scientists recorded a Cuvier’s beaked whale staying below the water for 3 hours 42 minutes. • The nearly blind star-nosed mole, the world’s fastest eater, can find and gobble down an insect or worm in a quarter of a second. It hunts by bopping its star against the soil as quickly as possible, touching 10 or 12 different places in a single second. • The 10 centimeter long cleaner wrasse, a reef fish, has joined great apes, bottlenose dolphins, killer whales, Eurasian magpies and a particular Asian elephant in exhibiting self-awareness.

• Some sauropod dinosaurs had necks stretching up to 11 metres (36 feet) long. • A monkey community on Kōjima island near the southern tip of Japan washes sweet potatoes in the sea, where they acquire a salty taste. This behavior is passed from one generation of monkeys to the next. This is cultural behavior. • By the age of five a chimpanzee named Ai learned eleven colors and that Arabic numerals can represent numbers. Ai can, for example, assign the label “Red/Pencil/5” when five red pencils are shown to her. • Near the Indian city of Kannauj certain plants secrete fatty acids into the soil to slow the growth of nearby plants, reducing competition when water is scarce. •  Hyraxes can stare into the sun, have tiny tusks, armpit nipples, and excrete a weird pee/poop substance in their group latrines used by perfumers and also as a folk remedy for epilepsy. • The oldest known wild bird on earth is a female Laysan Albatross named Wisdom. Scientists put a leg band on Wisdom in 1956, when she was already at least five years old. That puts her age at at least 70 years. In late 2020, Wisdom returned to her breeding grounds on Midway Island and successfully hatched and raised a chick, her 40th known child. • The tube worm takes advice from bacteria. It spends its earliest days drifting among plankton but selects where to metamorphose into its adult form by monitoring chemical signals released by bacteria. That suggests the bacteria are getting something in return. Speculation: the bacteria are helping to assure new habitat, which the growing body of the tubeworm will provide. • Giraffes’ eyes are among the largest of terrestrial mammals’, they can see in color and over great distances frontally, and their peripheral vision is so wide-angled they can essentially see behind themselves. Their mouths are like a set of human hands, with thick, prehensile lips and 18-inch-long, prehensile tongues which can together grasp a leafy branch and then deftly pluck away the leaves while avoiding intervening thorns. • The shaggy ink cap mushroom is capable of erupting through asphalt and lifting heavy paving stones overnight, although they are not themselves a tough material. No one knows how they do it. •

Hyraxes can stare into the sun, have tiny tusks, armpit nipples, and excrete a weird pee/poop substance in their group latrines used by perfumers and also as a folk remedy for epilepsy. • The oldest known wild bird on earth is a female Laysan Albatross named Wisdom. Scientists put a leg band on Wisdom in 1956, when she was already at least five years old. That puts her age at at least 70 years. In late 2020, Wisdom returned to her breeding grounds on Midway Island and successfully hatched and raised a chick, her 40th known child. • The tube worm takes advice from bacteria. It spends its earliest days drifting among plankton but selects where to metamorphose into its adult form by monitoring chemical signals released by bacteria. That suggests the bacteria are getting something in return. Speculation: the bacteria are helping to assure new habitat, which the growing body of the tubeworm will provide. • Giraffes’ eyes are among the largest of terrestrial mammals’, they can see in color and over great distances frontally, and their peripheral vision is so wide-angled they can essentially see behind themselves. Their mouths are like a set of human hands, with thick, prehensile lips and 18-inch-long, prehensile tongues which can together grasp a leafy branch and then deftly pluck away the leaves while avoiding intervening thorns. • The shaggy ink cap mushroom is capable of erupting through asphalt and lifting heavy paving stones overnight, although they are not themselves a tough material. No one knows how they do it. •  Some fungi species are able to harness radioactivity as a source of energy, similar to how plants use sunlight to grow. • The bar-tailed godwit migrates more than 7,000 miles annually between New Zealand and Alaska. • Birds may dodge storms by listening to infrasounds, low-frequency sounds inaudible to humans. Golden-winged warblers in the central and southeastern United States flew up to 9,300 miles in 2014 to evade an outbreak of tornadoes that killed 35 people and caused more than $1 billion in damage. The birds fled at least 24 hours before any foul weather hit, leaving scientists to deduce they had heard the storm system from more than 250 miles away. • Sub-Antarctic crested caracaras are rumored to spread wildfires by dropping burning sticks in dry grass and feasting on the ensuing stream of animal refugees. • Chimpanzees use medicinal plants. They consume fruits with antimicrobial properties; sometimes they combine them with other substances to reduce the toxicity. They eat flowers with antibiotic properties or leaves with antiparasitic ones, which act as laxatives or even induce uterine contractions. They also tear off bark and lick the resin to kill internal worms. • The peacock mantis shrimp’s limbs are so light and tough that scientists study them in the hope of creating new protective materials for human use. The shrimp uses them to stun or crack open prey, dig burrows, defend itself from predators, and fight against other shrimp. Its hammering is incredibly rapid, precise, and brutal: a speed of 100 kilometers per hour. The motion is among the fastest in the natural world — as if the little beast were firing bullets with a force of impact thousands of times its body weight. The attack occurs so rapidly, it’s invisible to the human eye. • One male oceanic dolphin was seen carrying a dead calf, accompanied by two female dolphins off the coast of Hawaii. No one knows whether the male killed the calf, which was thought to be the infant of the younger female. But by holding the body, he ensured the females stayed with him. • Puffins have two distinct phases of their lives: four months on land to breed, with the rest of the year spent out at sea. • Many young elephants who’d watched their mothers and relatives being killed went on to exhibit symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder. • Many fish see four major colours; humans only see three. Some see polarised light, some see ultraviolet. Some, such as flounders, move their eyes independently, processing two image fields. •

Some fungi species are able to harness radioactivity as a source of energy, similar to how plants use sunlight to grow. • The bar-tailed godwit migrates more than 7,000 miles annually between New Zealand and Alaska. • Birds may dodge storms by listening to infrasounds, low-frequency sounds inaudible to humans. Golden-winged warblers in the central and southeastern United States flew up to 9,300 miles in 2014 to evade an outbreak of tornadoes that killed 35 people and caused more than $1 billion in damage. The birds fled at least 24 hours before any foul weather hit, leaving scientists to deduce they had heard the storm system from more than 250 miles away. • Sub-Antarctic crested caracaras are rumored to spread wildfires by dropping burning sticks in dry grass and feasting on the ensuing stream of animal refugees. • Chimpanzees use medicinal plants. They consume fruits with antimicrobial properties; sometimes they combine them with other substances to reduce the toxicity. They eat flowers with antibiotic properties or leaves with antiparasitic ones, which act as laxatives or even induce uterine contractions. They also tear off bark and lick the resin to kill internal worms. • The peacock mantis shrimp’s limbs are so light and tough that scientists study them in the hope of creating new protective materials for human use. The shrimp uses them to stun or crack open prey, dig burrows, defend itself from predators, and fight against other shrimp. Its hammering is incredibly rapid, precise, and brutal: a speed of 100 kilometers per hour. The motion is among the fastest in the natural world — as if the little beast were firing bullets with a force of impact thousands of times its body weight. The attack occurs so rapidly, it’s invisible to the human eye. • One male oceanic dolphin was seen carrying a dead calf, accompanied by two female dolphins off the coast of Hawaii. No one knows whether the male killed the calf, which was thought to be the infant of the younger female. But by holding the body, he ensured the females stayed with him. • Puffins have two distinct phases of their lives: four months on land to breed, with the rest of the year spent out at sea. • Many young elephants who’d watched their mothers and relatives being killed went on to exhibit symptoms similar to post-traumatic stress disorder. • Many fish see four major colours; humans only see three. Some see polarised light, some see ultraviolet. Some, such as flounders, move their eyes independently, processing two image fields. •  Bees can add and subtract. They understand nothing — that is, the concept of nothing. • Boasting a wingspan of around five feet and the ability to fly at speeds surpassing Usain Bolt in his prime, the black vulture Coragyps atratus can consume 140g of Brazilian household waste a day. • A group of zebras is collectively called a dazzle. • The genus of jumping spiders called Portia prefers to hunt other spiders, employing a clever trick. Females build nests in curled-up dead leaves suspended in air by silk attached to rocks or vegetation. Courting males crawl down silk suspension ropes, stand on top of the nest and shake it in a specific way, luring the female into an ambush. • Nearly every insect species has at least one species of parasitoid wasp that specializes in eating other insects alive. “They don’t just kill them, they want to keep them alive for as long as possible.” • Sea urchins, insects, spiders, crabs, snails, octopuses, fish, birds and mammals, among others, use tools. • Kites and falcons in the outback pick up burning sticks from bush fires, carry these smoking embers in their beaks to areas of dry grass and drop them, starting new fires, triggering frenzied evacuations by small animals – which are promptly snatched from above by the waiting raptors. Indigenous Australians start fires in order to flush out game. Which came first? • Some flowers tailor their petal shape, color, texture or nectar’s scent or flavor to attract a single pollinating species. • In Japan, one crow population uses traffic to crack open walnuts: The crows drop a nut in front of cars at intersections, and when the light turns red, they swoop in to scoop up the exposed flesh. • The female tsetse fly gestates her young internally, one at a time, and gives birth to them live. When each extravagantly pampered offspring pulls free of her uterus after nine days, mother and child are pretty much the same size. “It’s the equivalent of giving birth to an 18-year-old.” • Huge, burly, and equipped with a venomous sting, robber flies occasionally catch and kill hummingbirds. • Flies enjoy sex. Some male fruit flies were paired with females that were receptive to sex, while others were paired with females that rejected sexual advances. Both groups of males were then given access to a solution laced with alcohol and another lacking it. The sexually frustrated males consumed more alcohol than their sexually satisfied compatriots. • The tiny Toxeus magnus jumping spider, also known as the black ant mimicking jumper, looks like an ant, walks like an ant and even waves its front legs in the air like a pair of antennas. Females secrete a milk-like fluid to feed their offspring, which contains about four times as much protein as cow’s milk, prompting scientists to reconsider what it means to be a mammal. • The Antarctic blackfin icefish thrives in the Southern Ocean at temperatures just above seawater’s freezing point with no scales, blood as clear as water and bones so thin, you can see its brain through its skull. • In the mountains of Central America, the Alston’s singing mouse produces arias of loud chirps that can last as long as 16 seconds, and each mouse produces its own distinctive song. •

Bees can add and subtract. They understand nothing — that is, the concept of nothing. • Boasting a wingspan of around five feet and the ability to fly at speeds surpassing Usain Bolt in his prime, the black vulture Coragyps atratus can consume 140g of Brazilian household waste a day. • A group of zebras is collectively called a dazzle. • The genus of jumping spiders called Portia prefers to hunt other spiders, employing a clever trick. Females build nests in curled-up dead leaves suspended in air by silk attached to rocks or vegetation. Courting males crawl down silk suspension ropes, stand on top of the nest and shake it in a specific way, luring the female into an ambush. • Nearly every insect species has at least one species of parasitoid wasp that specializes in eating other insects alive. “They don’t just kill them, they want to keep them alive for as long as possible.” • Sea urchins, insects, spiders, crabs, snails, octopuses, fish, birds and mammals, among others, use tools. • Kites and falcons in the outback pick up burning sticks from bush fires, carry these smoking embers in their beaks to areas of dry grass and drop them, starting new fires, triggering frenzied evacuations by small animals – which are promptly snatched from above by the waiting raptors. Indigenous Australians start fires in order to flush out game. Which came first? • Some flowers tailor their petal shape, color, texture or nectar’s scent or flavor to attract a single pollinating species. • In Japan, one crow population uses traffic to crack open walnuts: The crows drop a nut in front of cars at intersections, and when the light turns red, they swoop in to scoop up the exposed flesh. • The female tsetse fly gestates her young internally, one at a time, and gives birth to them live. When each extravagantly pampered offspring pulls free of her uterus after nine days, mother and child are pretty much the same size. “It’s the equivalent of giving birth to an 18-year-old.” • Huge, burly, and equipped with a venomous sting, robber flies occasionally catch and kill hummingbirds. • Flies enjoy sex. Some male fruit flies were paired with females that were receptive to sex, while others were paired with females that rejected sexual advances. Both groups of males were then given access to a solution laced with alcohol and another lacking it. The sexually frustrated males consumed more alcohol than their sexually satisfied compatriots. • The tiny Toxeus magnus jumping spider, also known as the black ant mimicking jumper, looks like an ant, walks like an ant and even waves its front legs in the air like a pair of antennas. Females secrete a milk-like fluid to feed their offspring, which contains about four times as much protein as cow’s milk, prompting scientists to reconsider what it means to be a mammal. • The Antarctic blackfin icefish thrives in the Southern Ocean at temperatures just above seawater’s freezing point with no scales, blood as clear as water and bones so thin, you can see its brain through its skull. • In the mountains of Central America, the Alston’s singing mouse produces arias of loud chirps that can last as long as 16 seconds, and each mouse produces its own distinctive song. •  The flower Impatiens pallida, among others, devotes a greater share of resources to growing leaves than roots when put with strangers – a tactic apparently geared towards competing for sunlight, an imperative that is diminished when growing next to siblings. • The marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri can distinguish when it is alone or in a group. It produces light through bioluminescence, similar to fireflies. If these bacteria are alone, they make no light. But when a group grows to a certain number, all of them produce light simultaneously. • To maintain its stealth, a bioluminescent anglerfish in the genus Oneirodes reflects as little as 0.044 percent of the light it encounters. The rest gets lost in a labyrinth of light-swallowing pigments until it effectively disappears. • Gobies, a type of fish, seem to remember complicated routes for almost 40 days. Several species, especially guppies, can recognise other individual fish, evidence of complex social engagement. • Chickadees produce alarm calls when they detect a potential predator to warn their fellow chickadees using their namesake “chick-a-dee” alarm call. The number of “dee” notes at the end of this alarm call indicates the danger level of a predator. “Chick-a-dee-dee” with only two “dee” notes may indicate a rather harmless great gray owl. When chickadees see a pygmy owl, they increase the number of “dee” notes and call “chick-a-dee-dee-dee-dee.” The number of sounds serves as an active anti-predation strategy. • Prairie dogs use their twittering alarm calls to describe approaching humans in detail, including information about their size, the color of their hair and clothes, and any objects they might be carrying.

The flower Impatiens pallida, among others, devotes a greater share of resources to growing leaves than roots when put with strangers – a tactic apparently geared towards competing for sunlight, an imperative that is diminished when growing next to siblings. • The marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri can distinguish when it is alone or in a group. It produces light through bioluminescence, similar to fireflies. If these bacteria are alone, they make no light. But when a group grows to a certain number, all of them produce light simultaneously. • To maintain its stealth, a bioluminescent anglerfish in the genus Oneirodes reflects as little as 0.044 percent of the light it encounters. The rest gets lost in a labyrinth of light-swallowing pigments until it effectively disappears. • Gobies, a type of fish, seem to remember complicated routes for almost 40 days. Several species, especially guppies, can recognise other individual fish, evidence of complex social engagement. • Chickadees produce alarm calls when they detect a potential predator to warn their fellow chickadees using their namesake “chick-a-dee” alarm call. The number of “dee” notes at the end of this alarm call indicates the danger level of a predator. “Chick-a-dee-dee” with only two “dee” notes may indicate a rather harmless great gray owl. When chickadees see a pygmy owl, they increase the number of “dee” notes and call “chick-a-dee-dee-dee-dee.” The number of sounds serves as an active anti-predation strategy. • Prairie dogs use their twittering alarm calls to describe approaching humans in detail, including information about their size, the color of their hair and clothes, and any objects they might be carrying.  The intraspecies conversations of octopuses, bees, and many birds follow a recognizable grammatical structure. Dolphins have unique names for one another, as do certain species of parrots, monkeys, and bats. • Chaser the border collie could identify and retrieve more than a thousand different toys by name and understand elements of English grammar. • Plants fight back. When caterpillars graze European maize, for example, the plants emit the volatile β-caryophyllene, which attracts parasitic wasps. The wasps lay their eggs inside the caterpillars, slowing their feeding and eventually, when the eggs hatch a few weeks later, killing them. • Some mushrooms can hunt. When food becomes scarce, some fungi build traps consisting of sticky loops or poisonous droplets, and with special substances, they lure nematodes into these traps. • When the male Great Argus pheasant runs into a possible mate, he clears a six-yard stage on the forest floor, picking up leaves, twigs and roots with his little white beak, finally beating his wings to blow away the debris. He struts around theatrically, pecking at the clear stage. Then he twirls out his wings, transforming himself into a dazzlingly large, intricately patterned circle, and starts vibrating, shaking and shimmering for up to 15 seconds before resuming his old form and returning to his routine, pecking the ground. •

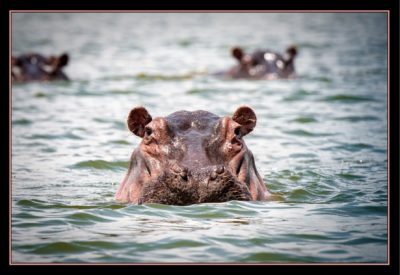

The intraspecies conversations of octopuses, bees, and many birds follow a recognizable grammatical structure. Dolphins have unique names for one another, as do certain species of parrots, monkeys, and bats. • Chaser the border collie could identify and retrieve more than a thousand different toys by name and understand elements of English grammar. • Plants fight back. When caterpillars graze European maize, for example, the plants emit the volatile β-caryophyllene, which attracts parasitic wasps. The wasps lay their eggs inside the caterpillars, slowing their feeding and eventually, when the eggs hatch a few weeks later, killing them. • Some mushrooms can hunt. When food becomes scarce, some fungi build traps consisting of sticky loops or poisonous droplets, and with special substances, they lure nematodes into these traps. • When the male Great Argus pheasant runs into a possible mate, he clears a six-yard stage on the forest floor, picking up leaves, twigs and roots with his little white beak, finally beating his wings to blow away the debris. He struts around theatrically, pecking at the clear stage. Then he twirls out his wings, transforming himself into a dazzlingly large, intricately patterned circle, and starts vibrating, shaking and shimmering for up to 15 seconds before resuming his old form and returning to his routine, pecking the ground. •  There have been several instances of an animal of one species helping an animal of a different species. For example, a hippopotamus was recorded lifting up a duckling that was unsuccessfully trying to get out of a pond, a bear rescued a crow from drowning and a cat attacked a dog that was trying to maul a toddler. • Spiders can fly, sort of, by electrostatic repulsion. They climb to an exposed point, raise their abdomens to the sky, extrude strands of silk, and float away. This is called ballooning. Ballooning spiders operate within the planet’s electric field. When their silk leaves their bodies, it typically picks up a negative charge. This repels the similar negative charges on the surfaces on which the spiders sit, creating enough force to lift them into the air. Spiders have been found 2.5 miles up in the air, and 1,000 miles out to sea. • The African crested rat chews on the bark of the poison arrow tree, then spits the masticated chunks all over its own hairs. It’s the only mammal we know of that uses toxins from a plant to make itself venomous. • The wings of Chinese tasar moths have scales that function like acoustic tiles. They absorb the sonar waves of predatory bats, making it very difficult for the bats to detect the moths with echolocation. • The Greenland shark, the eqalussuaq in Greenlandic, is the longest-living vertebrate on earth. Two hundred year-old eqalussuaqs are common, and some have been alive more than twice as long. A few still alive were probably born before Shakespeare, before the invention of telescopes or newspapers. Their nostrils aren’t needed for breathing (they have gills) but are used for smelling. They can smell small prey up to a mile away.

There have been several instances of an animal of one species helping an animal of a different species. For example, a hippopotamus was recorded lifting up a duckling that was unsuccessfully trying to get out of a pond, a bear rescued a crow from drowning and a cat attacked a dog that was trying to maul a toddler. • Spiders can fly, sort of, by electrostatic repulsion. They climb to an exposed point, raise their abdomens to the sky, extrude strands of silk, and float away. This is called ballooning. Ballooning spiders operate within the planet’s electric field. When their silk leaves their bodies, it typically picks up a negative charge. This repels the similar negative charges on the surfaces on which the spiders sit, creating enough force to lift them into the air. Spiders have been found 2.5 miles up in the air, and 1,000 miles out to sea. • The African crested rat chews on the bark of the poison arrow tree, then spits the masticated chunks all over its own hairs. It’s the only mammal we know of that uses toxins from a plant to make itself venomous. • The wings of Chinese tasar moths have scales that function like acoustic tiles. They absorb the sonar waves of predatory bats, making it very difficult for the bats to detect the moths with echolocation. • The Greenland shark, the eqalussuaq in Greenlandic, is the longest-living vertebrate on earth. Two hundred year-old eqalussuaqs are common, and some have been alive more than twice as long. A few still alive were probably born before Shakespeare, before the invention of telescopes or newspapers. Their nostrils aren’t needed for breathing (they have gills) but are used for smelling. They can smell small prey up to a mile away.

•••••

See the photos here and around 700 others in the Animals and Wildlife gallery at EarthPhotos.com.

December 15, 2021

Ethiopian Whoa

Just as the Covid cloud descended over us all I had a spring 2020 train trip planned on the brand new railroad between Addis Ababa and Djibouti. That seems now to be on hold beyond a mere pandemic. Best laid plans have fallen victim to civil war.

Ever since my first visit to Addis I’ve tried to convince mostly dubious friends that Ethiopia is as colorful and exotic as these photos, and welcoming and enriching at the same time. Now this.

•••••

Reading Around the Horn

No doubt that civil war is complicated. So here’s some background reading:

Find yourself a copy of Understanding Eritrea by Martin Plaut, and read his WordPress blog.

Alex de Waal is an academic at the Fletcher School. Two of his articles: What’s Next for Ethiopia, and Steal, Burn, Rape, Kill.

A few links to news from the region:

– Addis Standard

– A Muckrack list of articles from Awol Allo

– The International Crisis Group’s articles from Ethiopia and Eritrea

– Eritreahub

– Ethiopia coverage on Reliefweb

– The always opinionated Zehabesha

Neighboring Somaliland is busy with its own business, as presented in the Somaliland Sun. Djibouti doesn’t seem to have much to say in English (here is La Nation in French), but an expat named Rachel Pieh Jones sends a biweekly English substack newsletter from Djibouti called Stories from the Horn, in which she includes links to news from the region.)

December 9, 2021

Two Questions for You

With all those Russian troops menacing Ukraine’s eastern border, this morning I’ve changed our header banner to a photo from Kyiv. Just a little solidarity with the brave folks who have twice in the past twenty years taken to their streets to drive that looming Russian Red once and for all from their borders.

The questions: A reader has asked for a CS&W newsletter. I’m not sure the world needs another newsletter but I’d like to get your thoughts. So the first question(s): Would you like to see a monthly Common Sense and Whiskey newsletter in your inbox? What topics should it cover? And would it be worth a dollar or two a month to you? Please leave a comment or if you’d like to engage a little more personally, send a note to billmurraywriter (at) gmail.com.

Second question: The world is about to wrap up two frustrating years in which trying to get out on the road has ranged from downright frightening to impossible. So why not encourage a little armchair travel by giving a travel book as your holiday gift? I have four suggestions: Out There, Out in the Cold, Visiting Chernobyl and Common Sense and Whiskey. These links go to the US Amazon, but all four books are available from your country’s Amazon too.

Thanks for reading CS&W, and happy holidays.

New Column at 3QD

Here’s a link to my latest monthly column at 3 Quarks Daily. Hop over and read it there now, and I’ll publish it here in a few days.

No clues here what it’s about, except that these are the photos that accompany it:

December 2, 2021

Remember June? Boy, Was That the Best!

November 23, 2021

New On the Road Column

Here is my most recent travel column, as published (here) a couple weeks ago at 3 Quarks Daily. These columns appear once a month at 3QD, with the next one scheduled for Monday 5 December. This one is titled New Discoveries in the New World:

Consider the medieval mariner, slighted and sequestered, hard-pressed and abused, gaunt, prey to the caprice of wind and wave, confined below decks on a sailing ship. If the captain doesn’t get the respect he demands, he will impose it. So will the sea.

The sailor found solace in ritual. You get the idea he rather enjoyed taboo things. If the ship’s bell rings of its own accord the ship is doomed. Flowers are for funerals, not welcome aboard ship. Don’t bring bananas on board, or you won’t catch any fish. Don’t set sail on Fridays (In Norse myth that was the day evil witches gathered).

Helge Ingstad, an explorer we are about to meet, wrote that “Norsemen firmly believed in terrible sea trolls …. And those who sailed far out on the high seas might be confronted with the greatest danger of all: they risked sailing over the edge of the world, only to plunge into the great abyss.”

If they fell short of the abyss, what did they find? Fortunate men like Eirik the Red found safe harbors and hospitable enough terrain in Greenland to scratch out a life beyond the reach of Norwegian kings. Freedom.

No men found untold riches. More likely came calamity, hardship, deprivation. Life on an ancient sailing ship was a slippery log over a raging torrent. Yet medieval sailors pressed on, and the boundary of the world pushed ever farther west.

Fifty years ago Helge Ingstad and his wife Anne-Stein discovered remnants of a settlement in Newfoundland they suspected was the site known from Viking sagas as Vinland. The state of radiocarbon dating art a half century ago suggested the settlement was active between 990 and 1050.

We already knew certain artifacts around the Vinland site were cut down by metallic tools. This suggested the woodsmen were European, since indigenous people were not known to have metal tools. Then three years ago scientists established the “globally coherent signature” of a sunstorm in 993 CE by comparing tree rings. They compared forty four samples from five continents. This sunstorm (of a magnitude that has happened only twice in 2000 years) caused a readily detectable radioactive “spike.”

Finally, last month scientists applied their new tree ring knowledge to some of those same samples, from fir and juniper trees. Some even retained their bark, making it easy for researchers to count tree rings from the 993 “spike” outward. They conclude that an exploratory Norse mission to L’anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland, chopped down those trees in precisely 1021 CE.

•••••

Helge Marcus Ingstad’s big life spanned three centuries, 1899 to 2000. A wunderkind Norwegian lawyer at twenty-three, he chucked it all to live with an indigenous Canadian tribe for three years as a trapper, returned to Norway, became a governor in east Greenland, then governor of Svalbard, where he met his wife Anne-Stine.

For successive summers Helge and Anne-Stine sailed up and down Newfoundland’s west coast searching for evidence of Vinland. Year after year, it was mind-numbing, repetitive, wearying, wet work.

Everywhere they sailed they asked the same tired and practiced question. Did anyone know of any “strange, rectangular turf ridges?”

In the summer of 1960 the Ingstads called at a village on the northernmost tip of Newfoundland. They arrived by ship because there were no roads. Just thirteen families. And here, it turned out, someone did know of such ridges. On a sodden shoreline like endless others, they met George Decker, “the most prominent man in the village.”

Ingstad: “Decker took me west of the village to a beautiful place with lots of grass and a small creek and some mounds in the tall grass. It was very clear that this was a very, very old site. There were remains of sod walls. Fishermen assumed it was an old Indian site. But Indians didn’t use that kind of buildings, sod houses.”

The name of this windblown spot almost 400 miles north of St. John’s is L’Anse aux Meadows. Farley Mowat, the grand old man of Canadian adventure writing, calls this a distortion of the French L’Anse aux Méduses, or Jellyfish Bay.

The Ingstads spent that winter arranging an excavation to be led by Anne-Stine, by that time an archaeologist at the University of Oslo. It started the next summer and continued seven years.

Experts from Toronto and Trondheim collaborated to fix charcoal from the L’Anse blacksmith’s furnace, with the state of the tech at the time, as dating from 975 to 1020. The excavation revealed three stone and sod halls, five workshops, iron nails and decorative baubles consistent with the period. By 1961 they had authentic archaeological evidence that the Ingstads had found Vinland.

The team unearthed sod-and-timber halls built to sleep an entire expedition. The encampment lay tight against itself suggesting foreboding, a garrison mentality, uneasy disquiet in an alien land.

They built three halls between two bogs at the back of the beach near what they call today Black Duck Brook. Each had room for storage of turf, for what wood they found, for drying fish. A smaller area centered on an open-ended hut with a furnace for iron working, near a kiln to produce charcoal needed for ironworks.

Parks Canada has assembled replica buildings alongside the ruins, with detail down to spare blocks of peat for roof repair, turf squares stacked fifteen high like bags of potting soil on pallets at the garden center.

The recreated settlement

The recreated settlementOn a Wednesday in June, before summer has taken hold, smoke rises from a chimney in the main hall. There are four fireplaces the length of the building, fires for illumination and cooking, iron kettles for boiling stews.

The scent of wood smoke makes me eager to step inside, toward well-insulated, welcome warmth. You may shed your winter wear inside and you will be surprised how roomy is the interior space, much taller than a man.

An elaborate lattice weaves across the ceiling. The walls are extravagantly hung with ropes – coils and coils of line – a sailor’s colony. Against the back wall the length of the building run benches wide enough for sleeping, everything lined with skins.

It took twelve Parks Canada workers six months to craft that outdoor museum. Birgitta Linderoth Wallace, author of Westward Vikings, reckons that is comparable to sixty explorers working for two months of summer, or six weeks for ninety men. Surely these buildings were meant to withstand winter.

Maybe the Vinland voyages explored further south in summer. Maybe, as colder weather returned, so the men returned to L’Anse to winter, tell and embellish tales of their exploits and mainly, to stay warm. Excavations unearthed a soapstone spindle whorl that suggests spinning, possibly weaving. Perhaps the explorers brought bags of unspun wool, a worthwhile way to keep hands busy over the tedious winter.

•••••

In time the party encountered “skrælings,” local people unlike the Inuit they knew in Greenland. These were Native Americans, “short in height with threatening features and tangled hair on their heads.” The word skrælings is translated as “small people” by scholars, “screeching wretches” by the more flamboyant.

That first group of explorers, who built their settlement in tight formation, had been right to do so. The Greenlanders’ first encounter with other people did not go well.

One day the men came upon nine strangers sheltered under upside-down skin boats and the Norse killed all but one. The escapee returned next day primed for vengeance. The men saw countless canoes advancing from the sea, and the expedition’s leader, Thorvald Eiriksson, exclaimed: “We will put out the battle-skreen, and defend ourselves as well as we can.”

Battened down, the men withstood the skrælings’ attack unharmed except, calamitously, for Thorvald: As the skrælings fled he wailed, “I have gotten a wound under the arm, for an arrow fled between the edge of the ship and the shield, in under my arm, and here is the arrow, and it will prove a mortal wound to me.”

Thorvald Eiriksson became the first European buried in the New World and, dispirited, the Greenlanders soon departed for home. According to Linderoth Wallace, “the next expedition to Vinland is said to have been mounted for the explicit purpose of bringing his body back to Greenland.”

A clash on a subsequent expedition killed two more would be settlers. The Sagas tell us that the explorers realized “despite everything the land had to offer there, they would be under constant threat of attack from its prior inhabitants.” The Vinland settlement effort stalled.

Perhaps the explorers recognized all along they didn’t have the numbers for permanent colonization. Maybe the realistic among them never planned more than temporary missions to this continent-sized storehouse of supplies. Had they intended a sustained occupation there would have been a church and a cemetery, but there were none. The explorers never farmed the fields. Neither barn nor byre for cattle, no fold or corral for sheep.

Archaeologists found three butternuts, a tree never known to grow in Newfoundland, its range from southern Quebec to northern Arkansas. Their presence suggests the explorers traveled at least as far as New Brunswick, more than 400 miles to the southwest. Down there food may have grown wild, for “that unsown crops also abound … we have ascertained not from fabulous reports but from the trustworthy relations of the Danes,” wrote a German scribe in the 1070s.

Nowadays most everyone agrees the Vinland of the Sagas was a land and not a single, specific site like L’Anse aux Meadows. Vinland perhaps comprised an area from L’Anse along the Newfoundland coast south to Nova Scotia, down the St. Lawrence to present-day Quebec City where the river narrows, then up the opposite coast in a grand arc along Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Quebec and Labrador back to L’Anse.

•••••

Today is as fine a day as we have seen in northern Newfoundland, no sun but no rain and a fresh, steady, penetrating wind. Hardscrabble ground, uneven, firm enough if you are deft, but step off the rocks and you will sink to your boot tops in the bog.

Helge Ingstad wrote of a Norse “will of iron and a character able to endure privation and pain without a murmur,” and he must surely be right. Standing out by Black Duck Brook dressed in snug twenty-first century down clothing, I can not summon to mind the impossible hardship of men dressed in skins and bad footwear who sailed from Greenland in the cold and the wet, dodging icebergs, serrating wind and jostling seas.

A foot bridge crosses the brook leading toward the ruins. We modest few visitors pick our way up and down the paths. The original shelters, slumped back to Earth, now present as mounds, the effect a gently dimpled plain. Plaques identify the dimples: Huts and halls, the boat shed, the forge, the carpentry shop, the smithy.

Twenty people make a ring around the Parks Canada man in ranger-wear, who is fit to the place, wild and outdoorsy maybe like a pirate. He spins tales with a performer’s twinkle; his audience is all in. Sometimes he must raise his voice if the wind kicks up, bearing down across the Gulf of St. Lawrence from Labrador.

But walk away, find your own place, stand still, and the sounds slide away. Trifling waves come to shore too far away to hear. The cinematic clash of icebergs proceeds in acoustic stealth, distant enough not to disturb the quiet. Seabirds’ calls soar away on the wind and we are left only with the benign rustling of the tall grass.

Northern Newfoundland

Northern NewfoundlandWe stand by the brook. Helge Ingstad wrote in the 1960s, that “There is salmon in Black Duck Brook, we caught them with our bare hands.” George Decker’s grandfather told him there was considerable forest here in his younger days, but from the brook to the shoreline to Labrador this morning I am hard pressed to find a single tree.

The fog clears across the strait and Labrador emerges, brooding. Wisps of fog play up its cliff sides, snowy patches running up onshore. A peculiar lopsided iceberg, too heavy to bob, has shadowed us through the day.

In the course of an hour the fog recedes, pulling with it more character and definition from the icebergs, moving their surfaces from amorphous gray through bland white, in the end striking out toward the flamboyance of blue, even aqua.

The original European explorers stared hard into this view, wind burning their faces and blowing their beards as they ended their era of discovery one thousand years ago. Five hundred years before the European voyages that got all the good press, here at the end of their long road stood a mottled and murderous clan of northmen.

I imagine the view today is much as it was then. Expansive but spare, open to possibilities and full of challenge, but also full of promise. Two virgin continents awaiting the hand of European man. The original scruffy explorers left that promise for others to fulfill, but these rough-hewn men, standing here astride this earth wild and untamed, they had found the future.

November 14, 2021

Don’t Try This at Home. Or Anywhere Else.

This is a “steam therapy booth” in Dar es Salaam, a method Tanzanian authorities touted to protect against Covid. The President, John Magafuli, declared the virus a “satanic myth.”

“By this spring, the president was dead, along with six other senior politicians and several of the country’s generals. The official cause of Mr. Magufuli’s death was heart failure. The details remain secret. Diplomats, analysts and opposition leaders say he had Covid-19.”

(Photo from the article)

November 3, 2021

Submissive, Self-oppressive Nonsense

That’s how Timothy Snyder describes the American attitude toward air travel. It appears Mr. Snyder was not pleased with his recent experience with Delta Airlines. Read about it here.

(Note: This post sent me to EarthPhotos.com to retrieve the photo of the Delta jets up there, taken at Atlanta’s Hartsfield Jackson airport. In the EP Transport Gallery, there are 1058 photos of all sorts of different ways of getting around, from all over the world. Check it out, you might enjoy it. You can set up a slide show from the Transport Gallery main page by clicking where the arrow points, as below.)

November 1, 2021

On The Road: The Faroe Islands ‘Grind’

Here’s my most recent travel column for 3QuarksDaily, as published there a couple weeks ago. It’s a look at the Faroe Islands’ whale hunting tradition called the grindadráp.

Last month, local people drove fourteen hundred dolphins to the end of Skálafjordur Bay near the capital of the Faroe Islands and killed them. It is a tradition called the grindadráp. In Icelandic, one of the neighboring languages, “Good luck” is hvelreki, with an idea something like “may a whole whale wash up on your beach.” The Faroese don’t wait for luck to produce whales. They sail out and find them.

When a fishing boat or a ferry spies a pod of whales (dolphins in this case but usually whales), a call goes out and word races through the village. Even in the middle of a work day people drop what they are doing and muster. Fishing boats form up in a half circle behind the whales and, banging on the sides of the boats and trailing lines weighted with stones, press the whales into a shallow bay.

Townspeople wait on the beach with hooks and knives. Mandated under new regulations, two devices, a round-ended hook and a device called a spinal lance are designed to kill the whales more quickly and thus, grindadráp proponents say, more humanely.

The hunter plunges the hook attached to a rope into the whale’s blowhole. Men line up tug of war style to pull the whale onto the beach. It takes a line of men to haul them out, for pilot whales may weigh 2500 pounds. The grizzled fisherman, the mayor, the hardware clerk with a bad back, all the townspeople fuse in common cause, shoulder to shoulder on the shore, harvesting the meat, dividing the spoils.

The harvest is distributed evenly, for communal benefit. This is real, retail, hands-on constituent services for the mayor, who works out what size the shares should be and hands out tickets. People go to stand beside the whale indicated on their ticket. Those sharing each whale butcher it together, right there, right then. The municipality is mandated to clear the remains within 24 hours.

The animals are cut and pieces laid on the ground skin down, blubber up. Then the meat is cut from the whale and laid atop the blubber, the whole take is divided, and the shareholders gather up their haul and carry it home. There is no industrial processing.

Even today whale accounts for a quarter of all the Faroes’ meat consumption. Custom and tradition tip the scales against the advice of the then-Faroes’ Chief Medical Officer Dr. Høgni Debes Joensen, who declared in 2008 that no one ought to eat whale meat anymore because of the presence of DDT derivatives, PCBs and mercury in the meat.

Heðin Brú (1901-1987), perhaps the Faroes’ most important novelist, describes life in the village of Sørvágur, now adjacent to the airport on the island of Vagar, in his The Old Man and His Sons. Set in subsistence era early twentieth century Faroes, it describes the generational strains on a rural society being dragged into modernity.

Brú works to show the grindadráp (‘the grind’ for short), as vital in feeding the islanders. In 1928 a Faroese medical officer wrote, “…it cannot be emphasised enough how important this [pilot whale meat] is for the population, for whom the meat, be it fresh, dried or salted, is virtually their only source of meat.”

•••••

Once the grindadráp was a quirky cultural asset, but not anymore. In a time when people are quick to pass judgement, the grind pits the world against the Faroes. A tinge of the exotic attaches to today’s grindadráp, a summoning of vestigial heritage and pride, a suggestion that these quiet, unassuming subjects of the Danish crown fall into some bloodlust frenzy wild and savage, like Viking wildmen in helmets with horns only more authentic than horned Trump Sturmtruppen.

Now the Faroese live in a society modern in every way, right down to their efforts to find more humane ways to kill the whales, and whale meat is no longer required for the diet as it was in the days of Heðin Brú. The subsistence era was a different time. So the question arises, must the tradition continue?

Last month’s photos of the crimson harvest are revolting, and the idea of slaughtering some of the world’s most intelligent creatures is unsettling no matter who you are. But it must also be said that the Faroes’ intent is to be sustainable. The North Atlantic Marine Mammal Conservation Organization (apparently yes, that is a thing) reckons the annual Faroese slaughter takes less than 0.1 percent of the pilot whale population, the grind’s usual target.

Proponents call the grind socially adhesive, a big bundle of sport, tradition and a way of obtaining cheap food. It is also a direct link to the islanders’ past. Opponents assert that none of these justifications hold up in the 21st century. Yet in a place not very accommodating to agriculture, fishing – and pilot whales – have always been central to the Faroese diet.

You can be sure that isolated people will always mix resourcefulness with resistance to change. Pride, too. Pride in the ability to live and flourish in an outpost. Pride in the traditions that make the place unique.

Tjørnuvik

Traditions like the Stakksdagur festival. Every year in spring outside the postcard-perfect village of Tjørnuvik at the far end of Streymoy, strong men drive a few rams up into the hills to roam wild. On a Saturday as autumn approaches, islanders converge, out for a bit of tradition and a day of drinking and playing Viking, carry spiked wooden poles into the mountains, find the rams and use the poles to make a pen to confine them. To fanfare, commotion, camaraderie and traditional song, they herd the rams back into Tjørnuvik for slaughter and auction.

Call it the Faroese equivalent of tailgating on a college football Saturday. It’s as vaguely exotic as Scottish pole tossing, Swedes around the Midsummer pole or the Shetland’s Up Helly Aa.

When you’ve repeatedly been to the brink of starvation, when you live on a spot of land as precarious as the obstinate Faroes cliffs of slippery basalt, when your heritage reaches to Odin and Thor, when you have come through all this and more and today you thrive, perhaps there’s room for the stout view that your culture is worth preservation.

Elin Brimheim Heinesen, a Faroese musician, sharpens the point: “What is completely natural for people in the Faroes, seems so alien to other people, who have never lived here – or in similar places – so they can’t possibly understand the Faroese way of life. And thus many of the aspects of this life provokes them. People are often provoked or disgusted by what they don’t understand.”

She wants the casual visitor to understand that life still is really different on this small archipelago in a vast ocean, “that it is necessary to interrupt your daily work when the time is ripe to bring the sheep home and slaughter them, or go bird-catching, or go hare-hunting – or participate in pilot whaling – and, additionally, to prepare and store the food you have provided for yourself and your family. This food constitutes a large part of the total food consumption and is completely indispensable for most families – especially for the 12% in the Faroe Islands who live at or below the poverty line.”

Activists battle the grind and the Faroes’ legislature battles back. The parliament, called the Løgting, briefly voted in 2014 to ban members of the marine wildlife conservation organization Sea Shepherd from sending protesters. That legislation was dropped when Denmark determined it would likely be illegal.

But try, try again; a 2016 proposal to keep anti-whaling activists out equates actively protesting for an organization with work, for which foreigners require a work permit.

Hapag-Lloyd and AIDA, two big German cruise lines, have suspended or lessened arrivals in the Faroes to protest the grind. (This may be devastating to waterfront vendors but it has its appeal for those of us who believe there is a special place in hell for the inventor of the mega-cruise ship.)

The Faroese point out that the grind is an opportunistic hunt, not commercial, the meat is not exported and is shared across the entire community. The distribution of the spoils generally happens without money, and on the spot.

In the conservative British magazine The Spectator, Heri Joensen, the lead singer of the Faroese band Tyr writes, “In the Faroes, it is not uncommon to kill your own dinner — be it sheep, fish, bird or hare. I have slaughtered many more sheep than I have cut up whales and no one seems to care. I find that strange. Why the double standards? Because whales are endangered? The ones we eat aren’t. There are an estimated 780,000 long-finned pilot whales in the Atlantic. In the Faroe Islands, we kill about 800 a year on average — or 0.1 per cent of the population. An annual harvest of 2 per cent is considered sustainable: compare that with the billions of animals bred for slaughter.” Joensen says that buying the same amount of cow meat he got in a grindadráp would have cost more than £800.

So much discourse these days is about listing things one person or another ought not do. But I think most people don’t mean it, or at least don’t mean it deeply. Passing judgement on social media is a cheap way to signal group identity.

So much discourse these days is about listing things one person or another ought not do. But I think most people don’t mean it, or at least don’t mean it deeply. Passing judgement on social media is a cheap way to signal group identity.

It’s fair to say that one look at the business end of Skálafjordur Bay last month, crimson and slick with dolphin blood, turned legions of foreigners judgmental against the Faroese. The islanders counter that most of their critics, who live entirely apart from the source of their food, eat animals who suffer every bit as much as a grindadráp whale. Factory farming, they say, is an industrial scale horror for profit, while the grind has no financial motive. Who are you, they ask, to pass judgement on the people of a small group of islands far away?

•••••

There were some thoughtful comments added to this article at 3QD. Have a look at the comments here. Also see more photos of the very photogenic in the Faroe Islands gallery at EarthPhotos.com.