Annelies Pool's Blog, page 3

June 14, 2014

Family Spilling Over

I am reprinting this piece in honour of Thelma Tees, my friend, mentor and second mother who passed away 15 years ago today. “Family Spilling Over” was originally published in 2009 in the Anthology “Cup of Comfort for the Grieving Soul.”

I am reprinting this piece in honour of Thelma Tees, my friend, mentor and second mother who passed away 15 years ago today. “Family Spilling Over” was originally published in 2009 in the Anthology “Cup of Comfort for the Grieving Soul.”

I finally got the gravy boat.

For a year, I had avoided all thoughts of it because, once I got it, I’d have to accept the fact that Thelma was dead.

As long as it remained hanging on its nail in her cabin, there seemed a chance that I might go there one day to find her shuffling to the door in her slippers, a smile on her face, with a fresh story about how Katie put the run on a fox or dragged a dead muskrat up on the deck. There would be muffins in the oven, a kettle on the stove, and Thelma would bring out her best tea cups, the ones with the dainty gold filigree. She’d pour the first cup for herself and then say, as she always did, that she liked her tea weak. Katie would lie under the kitchen table twitching in doggie dreams and, when I sat in my usual chair, would put her head on my lap. I’d sip tea, relax into the rhythm of our chat, and the tension would flow out of my shoulders like mercury.

A year after Thelma’s death, my husband Bill and I were invited to a family get-together at her cabin to mark the anniversary of her passing. It was to be just like the old Sunday afternoons of summer, with Thelma’s grandchildren running, falling down, screaming, getting hugs and kisses, then running off again. There would be burgers and hot dogs on the fire, and we would balance on rickety chairs as we swatted mosquitoes and waved the smoke away from our faces.

But this time Thelma would not be there.

Thelma’s cabin was in the bush outside Yellowknife, Canada, a little over a mile from the place that Bill and I bought the year we married—the same year Thelma’s husband died, my mother died, Bill’s mother got sick, and Thelma became our new family.

I had been avoiding her cabin, hadn’t been there since the bright spring day a few weeks before she died when we’d gone over on our bikes and found her son gingerly helping his mother out of the truck. She was skeletal, drowning in her parka, but smiled as she lifted up her pant leg and made fun of the support hose she had to wear to help her circulation. We sat on the deck together for a few minutes, and an eagle swooped down from the sky, but Thelma was too weak to stay for long. Even then, the cabin had an unoccupied look, with weeds crawling up to the driveway and willows obscuring the view of the pond where we used to watch the ducks.

Now, I didn’t want to face the emptiness of her absence. Most of all, I didn’t want to face getting the gravy boat.

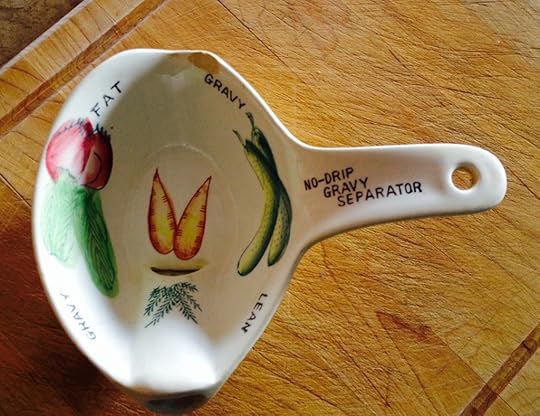

I’d first seen the gravy boat at one of Thelma’s family dinners, in the days when she was strong and lived in the cabin alone. It was the dinner where she forgot to take the stuffing out of the turkey and nobody noticed. How we laughed about it afterward. The gravy boat had two spouts: one at the top for fat and one at the bottom for lean. I was watching my weight then, and as soon as I saw the lean juice pouring out the bottom, I knew I wanted that gravy boat.

“Hmph!” Thelma said. “You won’t get it as long as I’m still alive!”

“Well, how long is that going to be?” I asked.

“You never mind!”

It became a standing joke between us. I kept trying to steal the gravy boat, but Thelma always caught me. She said she was going to live forever just so I would never get it. I would threaten to force her into an old-age home before her time so I could take it.

Thelma would look at me piously and say, “Let your conscience be your guide.” Then she’d add, “You know where you’re going when your time comes, eh?”

One day she said with a twinkle in her eye, “Show some respect for your elders. There will be a day when you come over here and find me lying dead on the floor. Then you’ll be sorry.”

“Well, that’ll be my chance,” I said. “If that happens, I’ll just step over your body, take that gravy boat off the wall, and march right out of here.”

We laughed. It was how we were with each other.

Then, it became serious. When Thelma got cancer the first time, when she was gaunt and crazy from her chemotherapy, she began to organize her affairs. She wrote my name in felt pen on the bottom of the gravy boat.

“When I go, come and take it,” she said. “I don’t know whether my kids will remember, but I want you to have it.”

I didn’t want the damn gravy boat anymore. I just wanted Thelma to go on living. I refused to look at it, refused to talk about it, and thought my refusal could somehow keep her alive.

She died anyway.

The barbecue to honour the anniversary of Thelma’s passing was family spilling over, as much like a barbecue in the old days as it could be without Thelma there. Thelma’s sister, Auntie Bertha, filled the role of matriarch. Thelma’s daughters, sons, and grandchildren, including two new great-grandchildren, were there, and the chatter was familiar. Auntie Bertha brought baked beans, and the kids squealed as everybody recited over and over, “Beans, beans, the musical fruit. / The more you eat, the more you toot.”

We laughed and laughed. Somewhere amidst the laughter, the screams, and the rhythms of affection, something in me let go and I began to accept Thelma’s death and enjoy being at the cabin again.

Toward evening, when Bill and I were just about to leave, Thelma’s daughter BJ called me into the house. I went inside, and she took the gravy boat from its nail on the wall and held it out to me. My name was still written on the bottom.

“Mom left it for you,” she said.

I reached out my hand. Now it was okay to have it.

Annelies Pool

Family Spilling Over

I am reprinting this piece in honour of Thelma Tees, my friend, mentor and second mother who passed away 15 years ago today. “Family Spilling Over” was originally published in 2009 in the Anthology “Cup of Comfort for the Grieving Soul.”

I finally got the gravy boat.

For a year, I had avoided all thoughts of it because, once I got it, I’d have to accept the fact that Thelma was dead.

As long as it remained hanging on its nail in her cabin, there seemed a chance that I might go there one day to find her shuffling to the door in her slippers, a smile on her face, with a fresh story about how Katie put the run on a fox or dragged a dead muskrat up on the deck. There would be muffins in the oven, a kettle on the stove, and Thelma would bring out her best tea cups, the ones with the dainty gold filigree. She’d pour the first cup for herself and then say, as she always did, that she liked her tea weak. Katie would lie under the kitchen table twitching in doggie dreams and, when I sat in my usual chair, would put her head on my lap. I’d sip tea, relax into the rhythm of our chat, and the tension would flow out of my shoulders like mercury.

A year after Thelma’s death, my husband Bill and I were invited to a family get-together at her cabin to mark the anniversary of her passing. It was to be just like the old Sunday afternoons of summer, with Thelma’s grandchildren running, falling down, screaming, getting hugs and kisses, then running off again. There would be burgers and hot dogs on the fire, and we would balance on rickety chairs as we swatted mosquitoes and waved the smoke away from our faces.

But this time Thelma would not be there.

Thelma’s cabin was in the bush outside Yellowknife, Canada, a little over a mile from the place that Bill and I bought the year we married—the same year Thelma’s husband died, my mother died, Bill’s mother got sick, and Thelma became our new family.

I had been avoiding her cabin, hadn’t been there since the bright spring day a few weeks before she died when we’d gone over on our bikes and found her son gingerly helping his mother out of the truck. She was skeletal, drowning in her parka, but smiled as she lifted up her pant leg and made fun of the support hose she had to wear to help her circulation. We sat on the deck together for a few minutes, and an eagle swooped down from the sky, but Thelma was too weak to stay for long. Even then, the cabin had an unoccupied look, with weeds crawling up to the driveway and willows obscuring the view of the pond where we used to watch the ducks.

Now, I didn’t want to face the emptiness of her absence. Most of all, I didn’t want to face getting the gravy boat.

I’d first seen the gravy boat at one of Thelma’s family dinners, in the days when she was strong and lived in the cabin alone. It was the dinner where she forgot to take the stuffing out of the turkey and nobody noticed. How we laughed about it afterward. The gravy boat had two spouts: one at the top for fat and one at the bottom for lean. I was watching my weight then, and as soon as I saw the lean juice pouring out the bottom, I knew I wanted that gravy boat.

“Hmph!” Thelma said. “You won’t get it as long as I’m still alive!”

“Well, how long is that going to be?” I asked.

“You never mind!”

It became a standing joke between us. I kept trying to steal the gravy boat, but Thelma always caught me. She said she was going to live forever just so I would never get it. I would threaten to force her into an old-age home before her time so I could take it.

Thelma would look at me piously and say, “Let your conscience be your guide.” Then she’d add, “You know where you’re going when your time comes, eh?”

One day she said with a twinkle in her eye, “Show some respect for your elders. There will be a day when you come over here and find me lying dead on the floor. Then you’ll be sorry.”

“Well, that’ll be my chance,” I said. “If that happens, I’ll just step over your body, take that gravy boat off the wall, and march right out of here.”

We laughed. It was how we were with each other.

Then, it became serious. When Thelma got cancer the first time, when she was gaunt and crazy from her chemotherapy, she began to organize her affairs. She wrote my name in felt pen on the bottom of the gravy boat.

“When I go, come and take it,” she said. “I don’t know whether my kids will remember, but I want you to have it.”

I didn’t want the damn gravy boat anymore. I just wanted Thelma to go on living. I refused to look at it, refused to talk about it, and thought my refusal could somehow keep her alive.

She died anyway.

The barbecue to honour the anniversary of Thelma’s passing was family spilling over, as much like a barbecue in the old days as it could be without Thelma there. Thelma’s sister, Auntie Bertha, filled the role of matriarch. Thelma’s daughters, sons, and grandchildren, including two new great-grandchildren, were there, and the chatter was familiar. Auntie Bertha brought baked beans, and the kids squealed as everybody recited over and over, “Beans, beans, the musical fruit. / The more you eat, the more you toot.”

We laughed and laughed. Somewhere amidst the laughter, the screams, and the rhythms of affection, something in me let go and I began to accept Thelma’s death and enjoy being at the cabin again.

Toward evening, when Bill and I were just about to leave, Thelma’s daughter BJ called me into the house. I went inside, and she took the gravy boat from its nail on the wall and held it out to me. My name was still written on the bottom.

“Mom left it for you,” she said.

I reached out my hand. Now it was okay to have it.

Annelies Pool

June 10, 2014

Good bye, Northwords

For the last five years I have been managing NorthWords NWT, first as its president and then as its paid executive director. NorthWords runs the annual NorthWords Writers Festival, programs for northern writers and has helped publish the anthology of NWT writing Coming Home: Stories from the Northwest Territories.

Last weekend I wrapped up my last NorthWords Writers Festival and I have now begun preparations to hand over the position of executive director to somebody else.

NorthWords has been a passion for me. I have poured my heart and soul into it. I have laughed over it and cried over it. NorthWords has made me grow as a writer and a human being. It has challenged me to do things I never thought I would be able to do. It has given me the courage to stand up in public and read my work for the first time and then to go on and publish my first book iceberg tea. It has also given me the amazing privilege of watching other northern writers take those same steps, and for anybody who has got up to a NorthWords mike or published for the first time in our anthology, I am proud of you like a mama.

I am at peace with my decision to leave and I look forward to the change in my life. But I am also very, very sad. While I expect I will always be involved in NorthWords in some way, I’m going to miss being the captain. I’d like to thank all of the NorthWords board of directors, both past and present, for giving the opportunity to go on this amazing adventure and I wish you all well in the future. I am looking forward to seeing the new ideas that fresh blood will bring to the organization and I wish the new executive director (whomever that may be) as much joy as I have had in doing this work. (I am also looking forward to being a NorthWords author without having to worry about whether the chairs are in the right place.)

Thank you again.

Good bye, NorthWords

For the last five years I have been managing NorthWords NWT, first as its president and then as its paid executive director. NorthWords runs the annual NorthWords Writers Festival, programs for northern writers and has helped publish the anthology of NWT writing Coming Home: Stories from the Northwest Territories.

Last weekend I wrapped up my last NorthWords Writers Festival and I have now begun preparations to hand over the position of executive director to somebody else.

NorthWords has been a passion for me. I have poured my heart and soul into it. I have laughed over it and cried over it. NorthWords has made me grow as a writer and a human being. It has challenged me to do things I never thought I would be able to do. It has given me the courage to stand up in public and read my work for the first time and then to go on and publish my first book iceberg tea. It has also given me the amazing privilege of watching other northern writers take those same steps, and for anybody who has got up to a NorthWords mike or published for the first time in our anthology, I am proud of you like a mama.

I am at peace with my decision to leave and I look forward to the change in my life. But I am also very, very sad. While I expect I will always be involved in NorthWords in some way, I’m going to miss being the captain. I’d like to thank all of the NorthWords board of directors, both past and present, for giving the opportunity to go on this amazing adventure and I wish you all well in the future. I am looking forward to seeing the new ideas that fresh blood will bring to the organization and I wish the new executive director (whomever that may be) as much joy as I have had in doing this work. (I am also looking forward to being a NorthWords author without having to worry about whether the chairs are in the right place.)

Thank you again.

February 10, 2013

Welcome to my new website

Hello everybody,

I am in the process of building a new website so please be patient. You might see some weird configurations on here in the next little while as I experiment but in the end it will be informative and fabulous.

December 21, 2011

So what kind Of Christmas will I have, anyway?

July 29, 2011

The Shackles of Dreams

Now I am old enough to bump up against the possibility that it may never happen.

Instead of being depressed about this, I find great freedom in this realization.

Dreams can be shackles and to age well is to let go of shackles. The older I get, the more I realize how little control I have. This is forcing me to release my grasp and enjoy the ride of life with all its mountains and valleys. In the end, I will measure my life by how much I've laughed and loved, not by how many books I've published.

That doesn't mean I've given up on the novel. I'm working harder than ever. It means I can do it with a lighter heart.

July 9, 2011

I'm so sorry, Will & Kate

It has just come to my attention that my book "iceberg tea" has become an international seller. I have sold the first (of many, I'm sure) copy on Amazon UK.

As soon as I heard the news, I began to wonder who in the UK would have ordered my book. Then it dawned on me that it must have been Will & Kate. It now seems obvious that they must have ordered it some time ago and their delight in the stories inspired them to include Yellowknife on their Canadian tour.

They must have been secretly hoping to meet me to get their copy of "iceberg tea" personally signed and dedicated.

Now I feel really bad for not going downtown the day they were here. I didn't go because I wanted to do some work on my next book and I thought the half-hour drive from Prelude into town, the hassle of finding parking and the wait in the crowd would all take too much time out of my day. Besides, I thought, I could probably see them better of TV.

That was before I knew about they were fans of "iceberg tea."

So what can I say now except, I'm so sorry, Will and Kate.

But, hey, next time don't be so shy. Give me call and I'll be happy to sign the book. Maybe we can even go roast wieners on the sailboat.

June 16, 2011

Thalidomide Characters

My character Marty who lives in 1980 thinks that he should buy a brand spanking new red 1981 Ford pick-up truck.

I want him to buy a used 1968 Dodge camper van that was refurbished by an RCMP officer in 1972.

He sees himself bombing up and down the highway in his new truck impressing all his drinking buddies.

I say he could have sex with his girlfriend, Jen, in the bed of the Dodge van.

He says he can have sex with her in the back of his new pick-up which is a crew cab.

I say maybe he should ask her about that first.

He says she's kinky enough to like it.

I say that if he buys the truck, he will throw a wrench in the story and I will never get it finished and doesn't he care about my literary career?

He says it's his story, what he does is none of my business and he never asked to be written in the first place.

I threaten to write all the money out of his bank account.

He says it's too late, that he already took all the money out and now he's got a big wad of cash in the front of pocket of his jeans.

So that's what that bulge in your jeans is, I say.

Don't be gross, he says. You're old enough to be my mother.

I ask how he took the money out of his account without my knowing about it.

He says it happened the night I fell asleep without turning the computer off, that as long as the computer's on and I'm not touching the keyboard, he can do whatever he wants.

What happens when I turn the computer off? I ask.

He says a big weight comes down in the middle of his chest that holds him in whatever place I left him until I come back. Now you've brought it up, he says, maybe you could be a little more considerate about where you leave me. He says he didn't appreciate being left down at the Old Town docks waiting for a cab for eight months.

Eight months? I say.

Yeah, eight months, he says. It was fucking cold and you shut it down before I had a chance to put on my toque. I got frostbite on my ears over that.

Oh, I say. That must have been when I got my new computer and I wanted to let your story rest while I worked with some other characters in another story.

Other characters, he says. I'm standing there at the docks freezing my goddamn ears off and you're out whooping it up with other characters.

Suddenly I feel like the worst kind of uncaring author, the kind of author who spawns half-baked, malformed characters with gimps, brain tumours or missing legs who are then left to fend for themselves. Thalidomide characters.

I sit and look at the screen.

Marty lights a smoke, turns his back and walks toward Jackfish Ford.

June 13, 2011

My Continuing Love Story

We went rowing in the rain today, the lake shrouded in mist, the air fresh as a new dawn. My pants were only slightly waterproof and as the downpour increased, I got soaked to the skin. I didn't care because the loons were calling and the rain pelted bubbles in the water and the slick black rocks of the islands rose into the mist.

I have always loved rain, ever since I was a little girl, and today there were no bugs, the rain was warm and the lake calm.

We took a break and I looked at Bill, wet dripping off his blue hat, Princess sitting in the stern behind him looking drowned and miserable and wondering why these people didn't have the sense to get in out of the rain.

Words bubbled from my lips unplanned. "I love you," I said to Bill. "I love you because if I hadn't met you, I would never have done anything like this and I wouldn't want to have to missed it for the world."

Bill said nothing but I could see a twitch in the corner of his mouth.

"I love rain," I said. "I married you because you're from Prince Rupert where it rains every day. I could see the rain in your soul."

He smiled his quiet smile. More rain came down and he picked up his oars.

"This is a great hat," he said.

"Oh, that's the hat Richard gave you," I said. "Richard likes to give gifts."

"Yes, he's a very generous fellow," Bill said.

We said nothing further then, just rowed through the rain in tandem and I reflected how, over the years of a marriage, love keeps renewing at the oddest of times. I would never have learned this if I had been too afraid to risk my heart.