Tim Wise's Blog, page 23

January 30, 2013

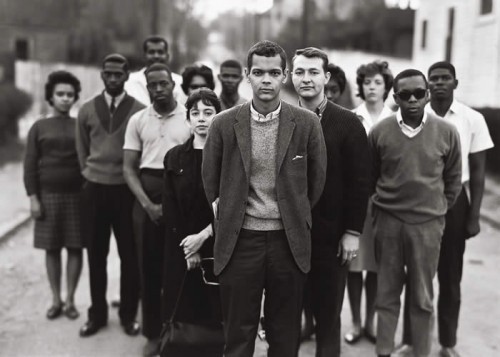

Because Occasionally We Need Inspiration…

…and if you need some, there are few images as capable of filling the bill as this one. This is, to me, the most inspiring photo from the civil rights era: Richard Avedon’s photo of the Atlanta SNCC staff in 1963 (and a few national leaders), including Julian Bond, Bob Zellner and Dottie Zellner. The focus, the intensity, the righteousness of this group, standing up in the face of American apartheid, reveals the best of the human condition and our potential. Fearless…real American heroes…sadly our history books tell our children little about them. So that becomes our job…

December 17, 2012

Race, Class, Violence and Denial: Mass Murder and the Pathologies of Privilege

The senselessness alone would have been sufficient.

So too the sheer horror.

The devastated families, the tapestry of their lives ripped apart, would have been more than enough to make the events at Sandy Hook Elementary almost too weighty to bear.

Much as they were more than a decade before at Columbine, or in any number of other mass or spree shootings — over five dozen by one count, more than 150 by another — that have played out over the past few decades.*

There is nothing, one would hope (and even suspect) that could make the present moment any worse.

And yet sadly, there is, and it is something that one hears almost every time one of these tragedies transpires. Over and again, no matter how frequently they happen, and no matter how often the specifics of the latest event eerily mirror the last one and the one before that — the high capacity weaponry, the apparent mental and emotional instability of the shooter, and the relatively bucolic surroundings of the locale where the deed is done — it is said again and again with no sense of irony or misgiving.

And it is maddening.

“This wasn’t supposed to happen here.”

Or perhaps, “No one could have imagined something like this happening in our community.”

Or even worse, “This is a nice, safe place,” which of course was the same thing said about Springfield, Oregon, Pearl, Mississippi, Littleton and Aurora, Colorado, Moses Lake, Washington, Jonesboro, Arkansas, Santee, California, Edinboro, Pennsylvania, Paduchah, Kentucky, and pretty much every one of the dozens of places where the things that never happen appear to happen regularly enough to constitute something well North of never; indeed quite a bit up from rare.

To have said merely that these things are not supposed to happen, at all, anywhere, to anyone’s children would have been both appropriate and more to the point, true. Six year old children are not supposed to die, whether from gunfire or untreated asthma, whether from violence or inadequate nutrition and medical care. Parents are not supposed to bury their children. Period. And yet every year millions upon millions around the world do, including untold tens of thousands across the United States.

But it is not enough, apparently, to simply remark that there is something tragic and unexpected and uniquely unacceptable about childhood mortality, and to leave it at that, to punctuate this most obvious and banal truism with a period and be done. No, it is that additional four letters, that one hanging syllable, that modifier of our shock and amazement, which localizes its unacceptability in a particular space — here. Not there, but here.

Still, after all these years, and all these sanguinary calamities, there remains the utter surprise that yes, evil can visit the “nice” places too. What’s that you say? Childhood death isn’t just for the brown and poor anymore? Not merely a special burden to be borne by the residents of South Chicago, West Philadelphia, or Central City New Orleans? There is dysfunction and pathology and general awfulness where some of the beautiful people too reside? Yes precious, yes indeed. This time would you please write it down; perhaps make it your Facebook status forever, so you won’t forget.

I don’t mean to be callous, and indeed I have shed plenty of tears for the families in Newtown, as I do every time one of these massacres takes place, as I sadly know I will again. But Goddammit, it is the denial, the cocoon-like innocence of the bleary-eyed denizens of these communities that drives me to distraction. Precisely because I do care, and I know that that very innocence — which now for the umpteenth time we get to hear has been shattered — is more than just maddening, and far more than an academic point. It actually helps to make these kinds of gut-wrenching catastrophes more likely.

After all, to whatever extent we place the blame for these things on widespread gun availability, we should know by now that with 280 million guns in circulation, that they can’t all be tucked into the waistbands of young black men who reside somewhere else; that at least some and by some I mean a frightful lot of them are surely stored in well-apportioned cases for display, in small towns and rural hamlets and suburban cookie-cutter cul-de-sacs and gated communities, by people who aren’t yet sure that their gates will suffice to keep the dreaded other (who never looks like their own disturbed son, but always someones else’s — darker and poorer) at bay. And so why are we surprised?

And to the extent we place the onus of responsibility on untreated mental illness, certainly we must know that emotional disturbance and chemical imbalance, the likes of which can, in some cases, lead to violent episodes, is no respecter of zip codes. Indeed, it may be precisely in those “nicer” places — to use the terminology to which we default whenever we speak of whiter and more affluent communities but would rather not admit exactly what we’re saying — where signs of emotional disorder, dysfunction and pathology are most likely to fly beneath the radar, in ways they never would in places where police, social workers, counselors, teachers and even parents are on constant lookout for signs of trouble, because they, after all, haven’t the luxury of being naive to the game.

Don’t misunderstand: It is certainly true that our entire culture has stigmatized mental illnesses — viewing them as somehow indicative of a weakness of will, or suggestive of an inherently dangerous tendency rather than the organic disorders they happen to be — such that many who need help will not get it, their conditions remaining undiagnosed and untreated. But this dreadful reality has a special ring of truth to it in those places where people are particularly used to keeping up appearances, and where they have the material and social privilege that allows one to keep one’s dirty laundry in one’s proverbial closet rather than having it aired for all the world (as is normative in poorer places). Is it so hard to imagine that in the “nice” and “quiet” communities where people are presumed to have their metaphorical shit together — and where being in firm possession of said shit is indeed a virtual condition of entry itself — that those who manifest dysfunctional and pathological tendencies might remain hidden, unhelped, and precisely because to admit of their issues would be to cast doubt upon the unsullied virtue of Pleasantville and those who call it home?

It is just a theory, a speculative musing that you are free to accept, reject, or ponder further as you wish. I cannot prove it; am not even sure that I believe it. But I can’t shake the nagging sense that it is more than a little possible. Surely we know it holds true in places like Littleton, where the Columbine killers had gone so far as to make a film in which they acted out the murders of their classmates and teachers, well in advance of their actual massacre; a film about which school officials were aware, but which failed to set off alarm bells in the way it doubtless would have had it happened in an urban school, or for that matter, had two of the handful of black kids at Columbine been the ones to have made it there.

And with reports coming out that the Sandy Hook shooter had evinced profoundly antisocial tendencies from an early age it is not unreasonable to wonder if such a child, in a community less stable than Newtown, and where any kind of odd and strange behavior is seen as a potential sign of trouble down the road (rather than being written off to nerdiness or geekdom) might have been intervened upon rather than left to his own devices and those of his mother.

Speaking of whom, can we really imagine a poor, urban, black or Latina mom successfully removing her disturbed child from the local public school so as to home school them, and then, in her spare time hauling him off to the shooting range to make sure he knew how to fire, among other things, an assault rifle? Once again, I am merely wondering aloud, but it seems something less than irrational to believe that maybe, just maybe, it was this family’s social position, their class status and yes, their race, which insulated them from the judgment and external control so regularly deployed against the poor and those of color who manifest drama in one of another guise.

They were from good families.

This is a nice, safe place.

Say it again. Say it a thousand times if it helps you get through your day, your week, your life.

But know this: the minute we as a nation lull ourselves to sleep, and allow ourselves the conceit of deciding that some places are beyond the reach of evil, of death, of pain — while others are not, and are indeed the geographic fulcrum of misery itself — two things happen, and both are happening now. First, we let our guards down to the pathologies that manifest quite regularly in our own communities — the nice places, so called — whether domestic violence, child abuse, substance abuse, or any of dozens of others; and second, we consign those who live in the other places — the not-so-nice ones in our formulation — to continued destruction, having decided apparently that in spaces such as that there is really nothing that can be done. They are poor, after all, and dark, and embedded in a pathological culture, and so…

At the very least let us agree that there is something of a cognitive disconnect here, linked indelibly to the race and class status of the perpetrators of so many of these crimes, when contrasted to the way in which we normally, as a nation, discuss crime and violence.

After all, when poor folks or people of color engage in criminal activity — including, in general, a disproportionate share of lethal street violence — everyone has a theory; and not just a theory but an analysis that in one way or the other implicates something cultural. For the right, it’s the culture of poverty, or perhaps some specific aspect of “black culture” — about which they know nothing but about which they also feel utterly qualified to speak — while for the left it’s the culture of systemic inequality, of economic marginality, or the cumulative weight of institutional injustice.

But when white people, and especially those from stable and even well-off economic backgrounds lash out in a manner often more bizarre, indiscriminate, and apocalyptic than even the most determined street thug, it is then that the value of broader cultural critique vanishes faster than ethical judgment on Wall Street, to be replaced by a far more individualistic analysis. It’s the guns in that kids home, or the video games he played, or the Asperger’s, or the bullying, or he was a loner, or watched violent movies, or whatever. Because we cannot bring ourselves to ask the questions, let alone countenance the possible answers that we would ask and at which we might arrive were the vast majority of these mass killers black, or Latino, or God forbid Arab Muslims. In any of those cases — and everyone with even a shred of honesty would admit it — we would be talking not about the individual killer as an aberration, as a disturbed and disordered soul who had lost his way. We would be talking about the group or groups from which they hailed. About their cultures, their religion, their pathological communities.

But Adam Lanza was not Muslim. Not black. Not brown. Not poor. He was a white man, just like about 70 percent of all mass and spree killers in American history. And no one seems to think this is very interesting or worthy of comment. Indeed, for even broaching the subject, the always astute David Sirota has been attacked all across the inter webs for his temerity. Attacked by the same people who would demand a racial and/or religious group analysis of the crimes had they been perpetrated in these percentages by any of the above groups to whom seven in ten such murderers most decidedly do not belong.

And no, I’m not saying there is something about whiteness that causes mass murder. But neither is there anything about blackness that causes the kind of retail crime we still see far too often in this nation’s cities; nor anything about Islam that is intrinsically connected to terrorism. And I’ll be more than happy to drop the line of inquiry I have so indelicately opened here if the rest of America will shelve lines two and three. But so long as we have people who insist on an inherent linkage between race and crime on the streets of Newark, or religion and terrorism the world over, I’m going to keep my argumentative options open, thank you very much.

Beyond the racial angle, can we also agree that perhaps there is something about a distorted notion of masculinity at work here? Is it merely coincidental that most of the perpetrators in these kinds of slaughters are something other than the media-hyped image of a man? That they are, so often, noted to be geeks and nerds? That they were bullied or picked on, or just ignored? Just as young women who fail to live up to the culture’s limited and constricting definition of an ideal heterosexual woman often develop destructive tendencies, usually directed inward, regarding body image, so too might men, struggling to keep up with the notion of manhood sold by Men’s Health, Maxim, and more to the point gun manufacturers, seek emotional sustenance from deadly hardware, body armor and the capacity to kill, not just the individual person with whom you have beef, but everyone in your general vicinity with a heartbeat?

Again, it’s just a theory, but so is every critique of the poor and those of color that has come down the pike in the last thirty years, or for that matter, forever. And it seems more than past the time when we ought to be willing to at least ask the questions, lest we be caught flat-footed, again and again and again, utterly paralyzed by the dysfunction that we continued to believe, against all evidence, would remain far from our placid environs, forever.

_________

* There are different interpretations of what constitutes a mass murder killing or spree killing. Mother Jones recently compiled a list limited to those events in which more than three victims (not including the killer) were murdered. Other events, involving mass killings over several days (some of which were counted by Mother Jones but others not), or events involving 2 or three victims are included by others and result in larger estimates.

December 15, 2012

Of Heroes and Hype: Mass Murder and the Absurdity of the ‘More Guns’ Crowd

As information continues to come in from Newtown, Connecticut — the scene of America’s latest mass killing, this time at an elementary school — there will be much said (and hopefully more to be done) in this nation and culture to diminish the likelihood of such tragedies occurring in the future.

But among the least fortunate, most absurd commentary, will no doubt be the cacophony blaring from the throats of conservative gun-fanatics, who will insist — as they always do in times like this — that if more people were allowed to carry guns openly on their person, tragedies such as the one in Newtown could have been prevented. Indeed, the rush to blame liberals and gun control advocates for essentially disarming teachers and others who, naturally, could have saved all those lives has already begun. Larry Pratt, of Gun Owners of America has intoned, for instance, that “Gun control supporters have the blood of little children on their hands.” Actually, of course, a gun owner — or rather, the son of a gun owner, represented, in effect, by Larry Pratt — has blood on his hands. The blood of 28 people; but never should one let the facts get in the way of a good lobbying volley, I suppose.

The idea that more guns, in the hands of more people, and the elimination of “gun free zones” at schools and elsewhere would reduce the likelihood of mass shootings — since would-be shooters would rationally fear being stopped by a skilled marksman and thus wouldn’t risk launching a killing spree (or even if they did they would be stopped before their carnage was completed) — is illogical on multiple levels. That the ridiculousness of the position really needs to be spelled out only attests to the fantasy-world-like mental simplicity of the gun crowd, but in any event, here it is.

First, and most obviously, the kind of person who is willing to commit mass murder is not likely to be open to the rational-minded deterrence that fear of an armed bystander might otherwise provide. Adam Lanza, like Dylan Klebold and Eric Harris and Wade Michael Page, and many others before him, was willing and prepared to end his own life at the conclusion of his rampage. If anything, thinking that someone else might have intervened and assisted them in their desired suicide would have only emboldened them, as the longstanding tradition of “suicide by cop” — where a disturbed individual provokes police to shoot them rather than doing the deed themselves — attests. Likewise, that an armed third or fourth party might have interrupted their killing spree after only a few had been felled, rather than a dozen, two dozen, or more, would also not have likely mattered much to them from the pre-emptive standpoint. Persons such as this will kill as many as they can, no matter the possibility that someone else might also be carrying, and thus prevent them from realizing the maximum desired number of victims.

But even the more limited argument, that someone else carrying a weapon could have at least minimized the number of dead in these instances, lacks any claim to rationality. Those who believe an armed teacher (or 2, or 3, or 5) could have stopped the Virginia Tech shooter, or the kids at Columbine, or Kip Kinkel, or most recently Adam Lanza, presuppose conditions at the scene that are absolutely fantasy-like, the stuff of video games, and surely bear no resemblance to the actual, real-world chaos that reigns in cases such as this. Simply put, it is one thing when one is serving in a war zone, or when one is a law enforcement officer, to come upon someone engaging in violent action, where confronting the shooter would be the logical and trained response. Soldiers and cops are prepared for such moments. But a kindergarten teacher or school principal or calculus professor, or whatever — even if that person is an expert shot — cannot be expected to react quickly and calmly enough to disarm a mass murderer. When such a person bursts into a classroom, the event is so utterly out of context, that the mere time it takes for those inside to even figure out what’s happening, would prove more than sufficient for these shooters to do their damage. So too in the Aurora, Colorado cineplex. Disoriented in that case by tear gas, an armed patron would have been firing blind into the fog, even presuming they would have had the presence of mind to pull their weapon and fire it at all. In cases like that, average people (again, as opposed to well-trained cops and soldiers) are thinking of saving their own lives, not engaging a killer in a hail of bullets.

For gun enthusiasts to claim that they could have taken down these killers if they had been there — or that others like them could have — is to play the role of Monday morning quarterback, operating with the benefit of hindsight, aware of what the shooter did and where they did it, such that they can somehow envision themselves, Rambo-like, crouching behind a door, or under a stairwell, or behind a chair and easily squeezing off enough rounds to spare lives and emerge the day’s savior. How easy it must be, and convenient, to retroactively ascribe to oneself the status of a would-be hero. That there are lots of legally armed citizens out there — and yet, none of them have ever stopped a killer in his tracks in the manner described by those who apparently have a hard time differentiating between “Call of Duty” and real life — apparently matters not to those for whom guns have become a political fetish.

Additionally, even if people had the right to carry guns anywhere and everywhere — schools, churches, bars, restaurants, ad infinitum — the gun nuts presume that therefore, a) lots of people would carry, b) those people would be sufficiently trained on how to use their weapons in a chaotic emergency scenario such that their carrying would result in a net increase in security in these locales, and c) that the net reduction in mass murder killings produced by concealed carry proliferation would end up outweighing the likelihood of those additional, open-carry guns, being stolen and used for the commission of crime, or accidentally discharged, resulting in death or injury. For instance, those who advocated that college students be allowed to carry guns on campuses after Virginia Tech seem to think that such forbearance would prevent another mass killing in the classroom, and that such a heroic scenario would be more likely than the possibility that some of those guns would be used to violently settle bar fights engaged by inebriated undergrads, or to resolve domestic disputes with fatal alacrity.

In other words, the “hero-with-a-gun-on-his-hip” crowd looks only at the incredibly rare and unlikely possibility of stopping a mass murder with more guns floating around, and pays no attention to the attendant risks on the other end of the equation, which suggests that long before those guns could be used for such beneficent means, more of them would find their way into the hands of persons with nefarious intent, or be used in far less constructive ways.

With all of this said, of course, it is true that tougher gun laws might not serve to deter many of these mass killing events either. In most cases, these kinds of killers are so deeply in the throes of untreated mental or psychological illness,* that they are unlikely to be dissuaded by a few additional obstacles to procuring weapons with which to injure, maim and kill their targets. But such obstacles, even if not completely sufficient for making us a safer nation, would surely make their actions — and the violent actions of many other, more pedestrian and retail-level killers — more difficult. The hurdles would become higher, the ease and simplicity with which mass killers can ply their trade at present would be made more complicated. Perhaps just long enough for the momentary schizoid or other mental break to pass, or the instant rage to dim, or for help to be procured by a teacher, counselor or parent armed not with yet another weapon, but rather, the necessary training to spot profound emotional disturbance and to obtain assistance for those in need of it.

But one thing is clear: the notion that because gun control won’t necessarily stop a given crime, it is therefore a useless gesture, is an argument unworthy of a civilized people. By that logic, there should be no limit on any kind of weapon — surface-to-air-missiles, personal tactical nukes, or tanks — since, after all, people who really want them will still get them. First off, uh, no they won’t actually. Law enforcement is perfectly capable of ensuring that no underground market emerges for those weapons, as with machine guns, for instance. To think they could not similarly enforce laws against high capacity, semi-automatic handguns, or assault rifles, is to believe them both competent and incompetent at once. Yes, the occasional killer, extremely motivated and resourceful will no doubt still find a way to kill people, as did Anders Breivik in Norway, for instance. But note, Breivik’s crime was extraordinarily rare in his nation. So rare as to be sui generis, in fact. Would that the same could be said about Adam Lanza’s deeds.

But here is the larger truth. Whether severe restrictions on gun ownership would save a thousand lives, or merely a handful now and then, really isn’t the point. The more important question is what kind of country do we want to be? Will we insist on remaining among the most heavily armed nations on Earth — and one of the most deadly, as if those things were merely coincidental — or will we seek to create a culture of non-violence, in which manhood is not defined beginning at an early age, as being related to fighting, hunting, shooting things for fun, and generally being physically tough? Bottom line: there is something wrong with a society in which so many people want and even seem to need guns, like some kind of psychological crutch; a society in which millions pay good money to watch two men get in a cage and beat the shit out of each other, and think to call that sickness a sport, or even worse, an art form.

Whether or not gun control can really work as advertised, guns, sadly, work exactly as promised. They serve only one function, and it is that purpose for which they were made: to kill, either an animal (usually for fun), or another person. To think that we would want more killing machines in the hands of a people who are so quick to resort to violence at the drop of a hat — to avenge global, or local “disrespect” by some foe, real or imagined, or to resolve otherwise minor squabbles — seems the stuff of true insanity.

In short, while guns alone don’t kill people, it is rather apparent that Americans do, and mostly with guns. And until we address the cultural sickness that lay at the heart of our national identity, it is quite clear that we are a people unworthy of access to such instruments of death as these. Perhaps somewhere there are people mature enough to handle guns responsibly. We have proven, over and again, and with the blood of our children, that we are not that people.

____________

* Please note, this is not to say that most mentally ill persons, or those suffering from a psychological disorder are themselves violent. Most are most assuredly not, even if a disproportionate share of mass killers may be reasonably said to suffer some type of emotional/psychological malady. Thankfully, violence among the mentally ill is rare, and mass killing even rarer.

November 26, 2012

Tim Wise on White Anxiety and The Future of Multiracial Democracy (GRIT TV), 11/16/12

Here’s an extended discussion of racism, white anxiety, institutional power and the future of multiracial democracy, from GRIT TV with Laura Flanders. This interview was conducted on November 16, 2012 at the Facing Race 2012 Conference in Baltimore.

November 18, 2012

Tim Wise on CNN Headline News to Discuss Race and Post-Election America 11/11/12

Tim Wise on CNN Headline News Weekend Express with Natasha Curry, November 11, 2012

October 18, 2012

Tim Wise on “The Rundown With Sirota & Brown,” AM 630, Denver – 10/17/12

Here’s my appearance from 10/17 on “The Rundown With Sirota and Brown,” on Denver’s AM 630. David Sirota used to have me on his old show quite often, and now appears opposite conservative host Michael Brown (yes, THAT one, as in, Michael “You’re Doing a Heckuva’ Job Brownie,” Brown, the former hapless FEMA director under W, during Katrina). I busted it off on him on affirmative action and race…Hey Brownie, that right there was for New Orleans dawlin’

October 6, 2012

Racism, Public Health and the High Cost of White Denial

This is the core of my speech at Georgia State, in Atlanta, in April, 2012, on Racism and Public Health. Here I discuss racial health disparities in the U.S., the way these disparities are ignored, explained away or rationalized by most whites, and the link between racial micro-aggressions and discrimination in health care delivery on the one hand, and worse health outcomes for people of color, on the other. I also discuss the unexpected costs of racial privilege for whites: the downside of developing an entitlement and expectation mentality and the larger societal costs of persistent inequities.

Redefining Cultural Competence

This brief sound file is from my longer talk on racism and public health, delivered at Georgia State University in Atlanta, April 12, 2012. I make the point that too often we define “cultural competence” as coming to understand the racial/ethnic/cultural “other,” so as to fit them in with the dominant cultural norm; yet the problem might be the “norm” itself, and perhaps the more important form of competence would be to come to understand the workings of the dominant group and its tendency to marginalize others.

September 16, 2012

Insights and Outbursts – Volume 2

Another collection of short sound clips from longer speeches, each one focused on a particular theme or sub-topic. For full descriptions of the clips, click below the audio player, where it says “Read the rest of this entry…”

1. From my September 2011 talk at Spalding University in Louisville, KY. In this snippet, I respond to a question about how we should understand or think about biracial and multiracial folks’ experiences in a system of racism/white supremacy.

2. From my September 2011 speech at Spalding University in Louisville. In this clip I discuss the way in which the U.S. clearly prioritizes incarceration over education, and analyze the systemic logic — however twisted — of inequality, and how it is “rational” from the perspective of those who benefit from the economic status quo…

3. Brief snippet from longer September, 2011 speech in Louisville at Spalding University. In this clip I discuss the importance of human empathy and the ways in which USAmerican culture devalues it in the name of patriotism and hyper-nationalism.

September 15, 2012

Racism 2.0 and the Burden of Blackness in the Age of Obama

Section from a longer 2008 speech, 10 days after the presidential election, in which I discuss how racism of a 2.0 variety — which I explain in the clip — may be in full effect despite the election of Barack Obama to the office of the presidency. I also explore how black folks and people of color generally must meet a much higher threshold of acceptability to white voters than white candidates have had to meet, in terms of education, erudition, style and affect, and how the “archetype of acceptable blackness” may become more constricting then ever with the election of President Obama

Tim Wise's Blog

- Tim Wise's profile

- 503 followers