Mary Reynolds Thompson's Blog, page 5

November 26, 2016

Poetry

And it was at that age… Poetry arrived

in search of me. I don’t know, I don’t know where

it came from, from winter or a river.

I don’t know how or when,

no, they were not voices, they were not

words, nor silence,

but from a street I was summoned,

from the branches of night,

abruptly from the others,

among violent fires

or returning alone,

there I was without a face

and it touched me.

I did not know what to say, my mouth

had no way

with names

my eyes were blind,

and something started in my soul,

fever or forgotten wings,

and I made my own way,

deciphering

that fire

and I wrote the first faint line,

faint, without substance, pure

nonsense,

pure wisdom

of someone who knows nothing,

and suddenly I saw

the heavens

unfastened

and open,

planets,

palpitating planations,

shadow perforated,

riddled

with arrows, fire and flowers,

the winding night, the universe.

And I, infinitesimal being,

drunk with the great starry

void,

likeness, image of

mystery,

I felt myself a pure part

of the abyss,

I wheeled with the stars,

my heart broke free on the open sky.

Pablo Neruda

(c) English version by Anthony Kerrigan

When did you first fall in love with poetry or a certain poem? Tell the story of what happened.

How do you honor your creative fire? And how does that fire feed your soul?

Begin a poem with the words, “And it was at this age…Poetry arrived…”

The post Poetry appeared first on Mary Reynolds Thompson.

Views from a Small Island: Fresh Perspectives on an Altered Landscape

The mood hung like damp laundry inside the Marin Airporter. It was the morning after the election, and I was on my way to teach at the Expressive Therapies Summit in New York. Three days later, I left New York for London.

It was the morning after the election, and I was on my way to teach at the Expressive Therapies Summit in New York. Three days later, I left New York for London.

Perhaps, like me, you’re still reeling from the election, scared for our world, and struggling to feel grateful in this season of giving thanks. So I want to share some insights gathered from the Psychology of Climate Change Conference I attended in London. What follows are views from a small island that offer a smattering of fresh perspectives. They don’t solve the problems we face, but they might just give you new ways to think about them.

Andrew Samuels, psychotherapist and activist, began the day by telling the audience to beware “Apocalypticism” – addiction to catastrophe. How might the adrenaline and excitement that we experience in the face of catastrophe be contributing to climate change? How does our Judeo-Christian mythology fuel this apocalyptic drive?

Indeed, doesn’t Shakespeare play his part as well? As here, in the famous speech by Hamlet that questions our very desire to live:

To be, or not to be–that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And by opposing end them. To die, to sleep–

No more–and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache, and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to. ‘Tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished.

And so we see how crisis can also be a kind of death wish, a desire to end the struggle and pain of living—a sort of mass suicide, where the “believers” enter the heavenly afterlife, while the unbelievers receive their just punishment.

How are we taking a stand for life? For resiliency? How can we refuse to buy into an End of Times vision?

Sally Weintrobe, a psychoanalyst who writes and talks about what underlies the disavowal of climate change, spoke of A Culture of Uncare. She began with a story of being in the desert with her husband when they discovered that they couldn’t open their food supply locker. Help was three days away. She split the dried peaches they had at hand between them, and then ate her entire portion in one sitting.

When our physical environment becomes unstable, she explained, we experience an equivalent inner instability that disables our capacity to care for our future selves. You can see how this applies to climate change and the uncertainties it provokes in us. We are literally burning through energy the way Sally burned through her dried peaches.

Sally continued: “Our most primitive fantasy is having non-caring parents who abandon us to die.” This fear of abandonment, she argued, makes us susceptible to leaders that offer “pseudo-containment” –or the promise that they will take care of all your needs. Trump, in other words, appeals to people traumatized by abandonment.

And wasn’t it those most abandoned by the system who voted in droves for Trump? A man who proclaims that he will create safety and stability—build a wall that is impenetrable to attack, where everything dangerous to America will be kept out. Where you will not be abandoned, but kept from pain, conflict, looked after.

Trump in his Trump Tower, personifies the archetype of strong man. While his approach is cynical, his archetypal energy is made for this time of uncertainty—and it might help us to recognize this.

Catherine Happer, of The Glasgow Media Group, spoke to the media’s culpability. Its ideology of cynicism, the way it relies on presenting contrarian views, for example, on climate change science, seeds suspicion about everything we read or hear. We are exposed to so many conflicting opinions, we don’t know who or what to believe. When Trump declares that everyone is lying to you––which, as Catherine pointed out, is very different from saying “I am telling you the truth”––people resonate. We are being lied to—constantly.

One thing that struck me as strangely absent in the conference, however, was any discussion of our relationship to the natural world. If we are to be called to become our greatest selves, bring forth our greatest efforts on behalf of the Earth, perhaps we need to remember that we are the Earth in human form.

As a woman at the Expressive Therapies Summit in New York said after taking Kate Thompson’s and my workshop “Restorying the Many Dimension of Psyche: An Ecology of Being”: “Until now, I never understood that I carry the wisdom of the Earth within me.”

It’s good to hear from many voices. We must explore them and feel into the truth of them.

But it is the Earth’s intelligence that will have the final say.

The post Views from a Small Island: Fresh Perspectives on an Altered Landscape appeared first on Mary Reynolds Thompson.

October 26, 2016

Foreseeing

Middle age refers more

to landscape than to time:

it’s as if you’d reached

the top of a hill

and could see all the way

to the end of your life,

so you know without a doubt

that it has an end—

not that it will have,

but that it does have,

if only in outline—

so for the first time

you can see your life whole,

beginning and end not far

from where you stand,

the horizon in the distance—

the view makes you weep,

but it also has the beauty

of symmetry, like the earth

seen from space: you can’t help

but admire it from afar,

especially now, while it’s simple

to re-enter whenever you choose,

lying down in your life,

waking up to it

just as you always have—

except that the details resonate

by virtue of being contained,

as your own words

coming back to you

define the landscape,

remind you that it won’t go on

like this forever.

(c) Sharon Bryan

Where are you in the journey of your life? Describe what you can see from there.

If your life was a landscape, what kind of landscape would it be? Would it be fluid like a river, or deep like an ocean? Would it be a desert or a forest? Let your imagination lead the way.

Begin a poem with the words, “From where I stand…”

The post Foreseeing appeared first on Mary Reynolds Thompson.

October 5, 2016

Becoming Animal

The power of language remains, first and foremost,

a way of singing oneself into contact with others and with the cosmos—

a way of bridging the silence between oneself and another person,

or a startled black bear, or the crescent moon soaring like a billowed sail above the roof.

Whether sounded on the tongue, printed on the page, or shimmering on the screen,

language’s primary gift is not to re-present the world around us,

but to call ourselves into the vital presence of that world—

and into deep and attentive presence with one another…”

(c) David Abram, Becoming Animal: An Earthly Cosmology

Write a poem that bridges the silence between you and another being, human or non-human.

Write about your relationship to language. As you reflect back on your words, see if their are ways in which your relationship to language mirrors your relationship to nature.

Read a poem a day for a week. Read your poems outside in nature. What do you sense happens when poetry fills the air?

The post Becoming Animal appeared first on Mary Reynolds Thompson.

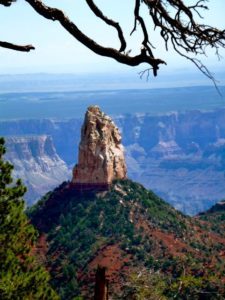

Seeing Deep Into Nature–Ours and the World’s

There’s an apocryphal story  that goes like this: When Captain Cook’s ship arrived on the shores of Terra Australis Incognito, or unknown southern lands, the Aborigines could not see it. This large ship was so beyond the realm of anything they had experienced, they were literally blind to it.

that goes like this: When Captain Cook’s ship arrived on the shores of Terra Australis Incognito, or unknown southern lands, the Aborigines could not see it. This large ship was so beyond the realm of anything they had experienced, they were literally blind to it.

I contemplate what this might mean for us in terms of our relationship to the natural world. Could it be that in separating from nature, in having it be something we increasingly know nothing about, we are in danger of not seeing it? Could we be moving beyond nature deficit disorder into nature blindness?

Mary Oliver, one of our most beloved poets, writes constantly of the need to pay attention to the world about us. To do so, she asserts, is a kind of prayer. We build a reverence for the world thorough attentiveness to it.

Any time you stop for a moment to notice the air, the light, the season, you are training yourself to see the world. The more you open up to a full bodied embrace to the world, the more she will reveal to you.

My work with earth’s archetypes provides another way out of nature blindness. Writes Robert Stetson Shaw, “You don’t see something until you have the right metaphor to let you perceive it.” When we see not only a tree, but a rooted presence, that is a living metaphor for some aspect of the self, then the tree is no longer some object to be viewed, but a part of the psyche to be experienced, acknowledged and integrated.

Metaphors help us see ourselves in the world and the world within us. Mary Oliver’s poems begin by focusing on the natural world, but always return us to our inner world. Thus a summer day spent looking at a grasshopper with enormous and complicated eyes, begs the question, “Tell me, what is it you plan to do / with your one wild and precious life?”

Ingesting nature’s metaphors we are coming to see, as Thomas Berry writes in The Great Work:

Only if our human imagination is activated by the flight of the great soaring birds in the heavens, by the blossoming flowers of Earth, by the sight of the sea, by the lightning and thunder of the great storms that break through the head of summer, only then will the deep inner experiences by evoked with the human soul.

In other words, in becoming blind to the natural world, aren’t we also in danger of losing sight of what makes us human?

The post Seeing Deep Into Nature–Ours and the World’s appeared first on Mary Reynolds Thompson.

September 7, 2016

Beekeeper

Beekeeper

Two seemingly conscious people

set their eyes upon the thistle.

One sees the weed. One sees the universe.

Therein lies the great divide.

Someone must speak for the

banished and the shunned, the

wounded and the way. Someone

must pray the wolves across the

ice bridge to Minong. Someone

must kneel alongside the part

of creation left dying on the side

of the road. Up over the ridge lives a

man who keeps bees. He sells his

honey or gives away to friends when

there’s plenty. He goes to

church where he is told of his

condition. The preacher sees a

poor lost sinner. God sees the Christ.

(c) James Scott Smith

From Water, Rocks and Trees

Do you see the weed or the universe? How does that perspective shape the way you live your life?

What do you pray for? The wolves? The dying left at the side of the road?

Begin a poem with the words, “I see the….” allow your love of nature to lead the way.

The post Beekeeper appeared first on Mary Reynolds Thompson.

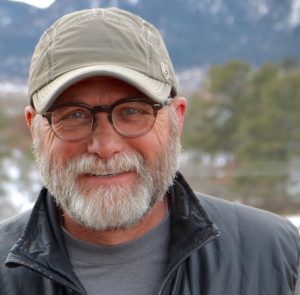

James Scott Smith’s Wild Soul Story

Poet, psychotherapist  and wilderness guide, James Scott Smith tells his wild soul story of spending time by a lake in Northern Ontario as a young child. Here, amid days of unstructured exploration, he describes being found by the sacred consciousness of the wild. His story leads up to one particular tale: Wild Raspberries. Told with the attention to detail you’d expect from a poet, and deeply reflective and wise, this is a Wild Soul Story to set your own heart stirring.

and wilderness guide, James Scott Smith tells his wild soul story of spending time by a lake in Northern Ontario as a young child. Here, amid days of unstructured exploration, he describes being found by the sacred consciousness of the wild. His story leads up to one particular tale: Wild Raspberries. Told with the attention to detail you’d expect from a poet, and deeply reflective and wise, this is a Wild Soul Story to set your own heart stirring.

Breaking from his formal career in 2006, James enjoys his family and home life, the Colorado backcountry, his dogs, fly fishing, photography and writing. James is the author of Water, Rocks and Trees, awarded Honorable Mention in the 2015 Homebound Publications Poetry Prize and available now where books are sold.

You can find out more about James’s book of poetry by clicking here.

The post James Scott Smith’s Wild Soul Story appeared first on Mary Reynolds Thompson.

July 14, 2016

Kai Siedenburg’s Wild Soul Story

A nature connection guide and writer

Wild Soul Story

who helps people cultivate intimate, mindful and juicy relationships with the natural world, Kai Siedenburg takes us on a walk into the woods close to Santa Cruz, California. There, practicing the skills of mindfulness and receptivity that she has developed over the years, she experiences a moment of deep intimacy with a bay laurel tree. Told with rich and loving detail, this beautiful story inspires us to seek out nature with a gentle heart and quiet mind.

As the founder of Our Nature Connection, Kai offers group programs, individual sessions, and consulting services. She has developed a large volume of nature connection tips and practices appropriate for diverse settings and is exploring opportunities to share them more widely. She also is writing a practical, poetic, and playful guide to connecting with nature for modern humans.

Kai’s work is co-created with the natural world—guided by the generous wisdom of trees and mountains, water and stone—and infused with love for people and the Earth. It also is informed by a 25-year career developing innovative educational programs for non-profits, and by extensive personal practice in nature connection, mindfulness, holistic healing, and creative expression.

You can visit ournatureconnection.com to find out more about Kai and to receive tips, original poetry, program information, and more.

The post Kai Siedenburg’s Wild Soul Story appeared first on Mary Reynolds Thompson.

A Journey through the Desert

In 2008, I began to submit articles related to  the landscape archetypes I write about in Reclaiming the Wild Soul. My first submission was “The Desert’s Gift of Emptiness.” One day, an envelope bearing the stamp of a University Press arrived in my mailbox. Acceptance or rejection? I opened the letter, barely breathing. Within minutes I was running up the stairs to my husband in tears.

the landscape archetypes I write about in Reclaiming the Wild Soul. My first submission was “The Desert’s Gift of Emptiness.” One day, an envelope bearing the stamp of a University Press arrived in my mailbox. Acceptance or rejection? I opened the letter, barely breathing. Within minutes I was running up the stairs to my husband in tears.

The editor of the press, a professor, wrote that I had trivialized the real concerns of how we treat deserts by implying that we treat our inner deserts, those places of silence and emptiness, in similar and equally harmful ways. That I would make the connection between deserts and the soul was ridiculous, according to him. Taking a serious environmental topic, he wrote me, and trying to make it a psychological one, was in his mind not only frivolous but dangerous.

I read the letter over and over. The tone was arrogant, condescending—and it filled me with doubt.

Was I really trivializing the great landscapes of the earth by drawing out their metaphors and meaning? Was I wrong to imply that human nature is deeply embedded in the natural world? Or that earth’s landscapes mirror aspects of our own psyches and souls?

And if we are nature, if the outer and inner life are joined, doesn’t it also follow that if we harm the environment we are also hurting ourselves—and not just physically, but spiritually and emotionally as well?

After agonizing over the letter for a few days, it occurred to me how strange it was that the professor had taken the time to write at some length. He could have sent me a generic rejection slip. So why hadn’t he?

What buttons had I pressed in him to inspire such disdain and verbosity? What, really, had upset him so very much about my “little” essay?

When we challenge a worldview, we inevitably spark rage and denial.

Our western culture’s tenet that humans are separate and superior to the earth allows us to believe that we can solve environmental problems in a purely rational and objective way. We don’t have to admit we’re heartbroken, that our bodies are wracked with grief, or that we are worried that a less vital world is actually impeding our ability to imagine and create new possibilities. That amid all this destruction of life, we are losing some part of ourselves too.

No, much better that we keep humans and the Earth in separate spheres—that we cut ourselves off from our earthy roots. Much better to dismiss any notion that a denatured world might affect human nature. Much safer to put up partitions, to slice and dice and not look at ourselves as part of the whole. And if anyone interferes with that thinking—just let rip and put them in their place.

It took me a week to throw away the letter.

A few days later, I received my first acceptance from a small publication called Front Range Review.

It was a beginning.

The post A Journey through the Desert appeared first on Mary Reynolds Thompson.

June 8, 2016

Finding Beauty in the Broken

I have a ritual upon returning home from my travels. The first morning back, I take the trail behind my house, up the hillside, up another steep single track, until I reach a rocky outcrop that is for me an altar. I pray there, to the trees, sky, bay, mountain. I have planted acorns as wishes and buried loved pets close by. It’s my special place, and now I am trying to open my heart to it. And struggling, a little.

I have a ritual upon returning home from my travels. The first morning back, I take the trail behind my house, up the hillside, up another steep single track, until I reach a rocky outcrop that is for me an altar. I pray there, to the trees, sky, bay, mountain. I have planted acorns as wishes and buried loved pets close by. It’s my special place, and now I am trying to open my heart to it. And struggling, a little.

I returned form England and couple of weeks ago. The last weekend was spent teaching “Reclaiming the Wild Soul” at Hawkwood College in the Cotswolds. May in Stroud is a jolt of every shade of green. The grass so lush, I watched a frog, small as a thumbnail, navigate it as if it were the Amazon rain forest. Late one evening, Bruce and I hiked in the woodlands in drenching rain under a canopy of beech, larch, hazel and ash. It was like entering a green womb, I felt so held and protected.

Back here, the grasses are prickly dry and crackle like gold coins. Beautiful to look at, but hard to the touch. In places they are turning that strange salmon pink that is usually reserved for later in the year.

It’s dry in California. Parched. And the political season has made us all equally prickly and fractious; the slightest spark, one feels, and it will all go up in flames.

And so, a part of me longs for the gentleness of English meadows. Not this—the tough, spiky, dry terrain with which I’m surrounded, quite literally, on every side.

And yet this is the new reality. The drought isn’t going away anytime soon. California will get dryer, hotter, more tinder-like with climate change. And we, too, will likely lose our cool much more often.

So how to love this changed and broken world? How to love grass that dries out too fast and too soon? And people that are barbed and prickly? How to open our hearts when everything seems to be hurting, harmed, and less hopeful?

I don’t know the answer. But standing by my altar on a high ridge with Mount Tamalpais in the distance, I am reminded of the words of Terry Tempest William:

May we all learn to find “beauty in a broken world.”

The post Finding Beauty in the Broken appeared first on Mary Reynolds Thompson.