Jeff Goins's Blog, page 29

February 17, 2017

How I Wrote And Launched A Book In 30 Days Even Though I Didn’t Think I Could Do It

I just wrote and launched an ebook in 30 days. It wasn’t easy, it wasn’t pretty, and yes I did ugly cry. Despite this, I faced my fears and tackled my paralyzing perfectionism to break through and do the unthinkable… make money from my art.

This is the story of how I created a simple product my dream clients actually wanted, wrote over 30,000 words in about a month, and then launched my book, Simple Is The Cure, to my email list of under 500 subscribers to make $800 in a matter of a few weeks.

Last year I was able to attend the second annual Tribe Conference. While there I was privileged to join the VIP mastermind group where Jeff personally spoke into my struggles as a writer.

During the mastermind roundtable, he hopped over to my group, listened to me state my case and matter of factly delivered an assignment to me:

“Write a 30-day devotional combining all of your knowledge as a health coach, artist, and minimalist. Then launch it. We can make you $1000 from the launch easily.”

After our conversation at Tribe, Jeff decided that in order to make the most impact I would need to refocus my efforts. This assignment was never about just making money. If it were, then I’d probably fail and he made that clear from the word go.

“Get 30 women, survey them about their biggest health concerns, and coach them every day for 30 days, getting feedback along the way. When this is over, you’ll have a set of 30 things that people really want, and case studies to prove that what you teach actually works”.

Here’s a step-by-step look at how I took Jeff’s assignment and instructions and implemented them to get the above results.

Tickets for Tribe Conference 2017 are available now! Click here to take advantage of the super early bird discount.

Define the project, set a deadline & go public

Right from the start, Jeff asked me to let my email list know that I was writing a book. The basic instructions from were:

Tell them it’s coming

Tell them it’s almost here

Help them get wins

Tell them it’s here

Let them buy

The plan was clear from the beginning. I would create a product based on what people said they wanted, give people what they said they wanted, get feedback, tweak, pre-sell, build hype, launch, make money, serve more people.

We agreed that the scope would be 30 women getting free coaching for 30 days for the entire month of November. December would be all about writing the draft and pre-selling. And in January, I would build interest and launch the final product. Admittedly, we originally wanted to launch by January 7th, but ended up moving the launch date to January 31st.

Gather a group of willing participants

I’m blessed to have such an amazing network of friends and acquaintances that were willing to join me for an experimental 30 days of simplifying life, health, and wellness.

In October, I wrote a quick introduction email to a list of 30 women I handpicked letting them know what I was doing and how they could get free coaching for 30 days. From the start I let them know that I was doing this project to collect material for a book that would later be for sale.

I started a private Facebook group and started adding people who were on board.

Give them what they want and teach what you know

I then surveyed each of them asking what their biggest struggles were around health, wellness, spirituality, home environment, fashion, etc. I asked them what they wanted to learn about and what would be of most help to them.

The feedback I received directly informed what I taught.

Once the Facebook group was up and running, I gave them a start date (November 1st), some basic rules, and a quick outline of what to expect. I did most of this through videos or Live broadcasts within the group itself.

Shorten the feedback loop

November 1st came and I was so unbelievably nervous.

Could I do this for 30 days straight? I’m a procrastinator. What if they don’t get any value out of this? What if I fail?

I had a lot of physical resistance, but knew to expect this because Jeff warned me that I’d be “kicking and screaming the whole way”. That’s an actual quote.

Day 1 was a video about setting intentions. I gave a quick setup and the assignment and it was done. People watched, people commented. It worked! Hooray. Only 29 more to go.

As I posted more videos, I got more feedback which I implemented. None of the videos were professionally done, scripted out, or beautifully shot. I used my iPhone and my 10 year old MacBook. The key was showing up and giving them what they wanted to the best of my ability.

It wasn’t perfect, which gnawed at every single perfectionist bone in my body. Rather than waiting till I knew what I was going to say or do, I had to act on the feedback of the group.

At Tribe Conference last year, Tim Grahl said that to make progress quickly it’s best to shorten the feedback loop. Don’t wait until you’re three quarters of the way into a project before asking for advice. Get it early and course correct.

This is what I did and it actually became a huge comfort to me. The group was my guide so that I could be theirs.

Get testimonials and determine pricing

November was a fun month. I did 31 or 32 videos in 30 days, had over 20, 1 hour coaching calls, and helped women get clear on what they actually need to be healthy, less stressed, and more balanced.

When the 30 days wrapped, it was time to get more feedback. I wanted to know:

Where they started

What they overcame

Where they ended up

What was most helpful

What they would ideally pay for the work we did together

I used this information to price the book at $19.00 to start with. A lot of the women said they’d pay $50, $150, or even $500 for the work we did together. When we landed on $19.00 for the pre-sell price and $29.00 for the final price, it felt like a steal.

In fact, I was giving my tribe what they said they wanted a price that they wanted and felt was more than fair.

Pre-sell to prove viability

You might think that pre-selling a book or product before it’s even complete is either insane or dishonest. But I was just following orders.

Jeff asked me to set up a link on Paypal, and send a quick email to only five people from the group letting them know the book was available for pre-order.

Of the five, two people pre-ordered and one was my mom. Thanks mom!

Even though it was only two people, I had what I needed to move forward. My product sold. That’s all that mattered.

Go into a cave and write

During the 30 days of coaching, I was keeping a very, very rough draft going in Google Docs. I did this for three reasons.

I wanted to fill in snippets on the go which I could do from my phone.

Google Docs allows you to dictate your content onto the page. So, I would often speak whole sections in when I was feeling stuck. Later, I could go back and have something to work with.

I loved that I could see the entire outline of my content on the left sidebar. This helped me have a clear understanding where I was in the project at any given stage.

Ultimately, I ended up using Google Docs for the entire project. I chose three fonts to work with and played with the formatting so that I could make it look super slick.

Finish and go ugly early

One of the things that got me through, was Jeff sharing a quote from Tribe Speaker Alumni, Whitney English. Go ugly early.

My goal was to finish; to ship it. December is a crazy time of year for everyone. It’s even more insane when you’re trying to write a book.

“Go ugly early.Whitney EnglishTweet thisTweet

Writing was slow and arduous at this time. I plugged in what I could but needed the month of December to hammer out the details and outline of the book.

I also used this time to get more feedback. I shared the earliest rough draft (aka the ugly draft) with my group before it was even halfway complete. I asked them if I was on the right track and what I needed to change.

Create a sales page

Jeff asked me to build a sales where people could learn about the book and order it.

The sales page copy was based on an article from guest blogger, Ray Edwards. You can take a look at that article over here.

Use a minimum viable product to build hype

All of January was about building interest within my community.

At this point, I was still writing feverishly and feeling like it would never come together. Even though I felt far away from my launch deadline of January 31st, Jeff told me it was time to start raising awareness.

I did a free 7-day video series all about how to live a cleaner, better life from the inside out. Every day for 7 days, I invited people to join my email list to participate in this free video training series (again, shot on my iPhone).

My email list went from 346 to 356. People were interested. I shared the videos on Facebook and YouTube.

In these video’s I told people to pre-order the book at $19.00 because they would receive 3 super cool freebies. Also because after the 31st of January, the price would go up.

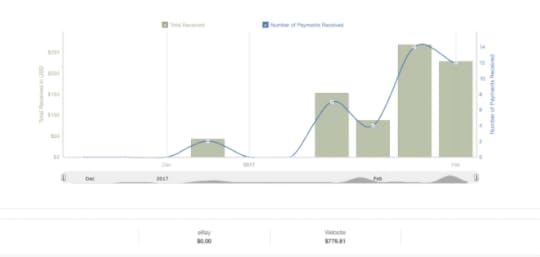

I had a total of seven sales during that pre-launch phase, four the week after, and 14 the week after that. Last week I sold 13 copies (one cash sale). This plus the two I pre-sold in December comes to 40 sales at $19.00.

What’s next

All in all, I’m insanely proud of this project. I still have a lot of work ahead of me, but now I have the framework I need to keep moving forward and spreading the message of simple solutions to optimize health and wellness.

The most important thing is that I broke the seal. I have a product. I have knowledge and confidence that I can use to keep moving forward.

Let’s not stop here

If you want to learn more about how to optimize your health and life with simple changes, you’re invited to subscribe to my blog where you’ll get access to a free 7-day video course all about how to live a cleaner, better life from the inside out.

Tickets for Tribe Conference 2017 are available now! Click here to reserve your spot and connect with other writers like Brianna.

What kind of product are you struggling to create? How could you apply lessons from Brianna’s story to start moving the needle? Share in the comments.

February 13, 2017

How to Fall Back in Love with Writing

It will happen. Eventually. You’ll do something you love, and after awhile, you’ll forget why you started. You’ll build a platform that’s successful, and it won’t matter. You’ll grow to resent the thing that brought you so much attention.

You’ll find yourself writing for the approval of others and no longer be satisfied with your craft. You will feel trapped.

But this is not the end. It’s just the beginning. You’ve yet to create your best work. To live (and write about) a life that inspires others.

It wasn’t until I stopped writing for accolades that I found my true audience. Not surprisingly, I’ve seen more writing success in the past year than in the previous five.

This is the paradox:

When you stop writing for approval, your work will move more readers.

So how do we do this? Where do we begin?

There are three shifts I went through that helped me fall back in love with writing.

“When you stop writing for approval, your work will move more readers.Tweet thisTweet

Become a writer (again)

A few years ago, a friend asked me what my dream was. I told him I didn’t have one. He called my bluff, “You know, I would’ve thought your dream was to be a writer.”

I said that was true, I guess, that I wanted to be a writer. One day. If I was lucky.

He told me, “You are a writer; you just need to write.” So that’s what I did. I started writing. Every single day. And the crazy part: I started to believe I was a writer.

Here’s how you can, too:

Turn pro. Steven Pressfield, author of The War of Art , says you have turn pro first in your head before you can do it on paper. I had the opportunity to interview Steve once, and I asked him when you become a writer. He said, “When you say you are.” Before others believe what is true about you, you’ll have to believe it first.

Find your voice. If you’re a communicator, we’re relying on you for insight, not to pander to us. You have to be yourself — to speak in a way that is true to you. The best way to do this? Practice.

Write for yourself. The only person you need to worry about writing for is you. This is the secret to satisfaction: doing what you love and enjoying it when no one’s watching. The funny thing is when you do this, you’re not really writing only for yourself. There are a lot of people just like you.

“The only person you need to worry about writing for is you.Tweet thisTweet

Pursue your passion

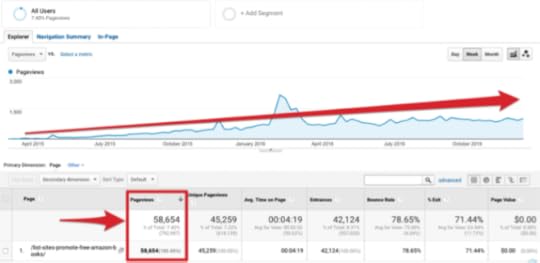

For five years, I wrote a blog that nobody read. I measured traffic and stats. I did everything possible to maximize the impact.

All the while, my heart slowly died, and I grew bitter. I watched other writers succeed in ways that I hadn’t and envied them. Eventually, I resented them. Why? Because I wasn’t doing what I wanted. I wasn’t enjoying the process. I was only chasing results.

So I went back to the basics: writing for the love of it. Not profit or prestige or even analytics. Just for doing it for the sake of doing it. You can, too, if you want.

Here’s how:

De-clutter. There are a million distractions in our world. The biggest for me is social media. You know what being a member of 25 different communities really is? Stalling. Procrastinating the real work, which is writing. If you try to stay on top of every new fad, you’ll spread yourself too thin. You can’t create and react at the same time.

Cancel contingencies. Most writers have more ideas than they know what to do with. They have a hundred half-written articles and a few books in them. How much have they finished? None. Do you know what’s really at work here? Fear. Of picking one thing and sticking with it. Here’s the truth: There is no wrong thing. Just begin.

Fail forward. As you cancel contingencies and find something to stick with, you’ll need to learn how to ship. To move through fear, which means you’ll have to face the inevitability of failure. Real artists fail every day. Why not embrace it instead of running away? When you fail, you don’t really fail. You learn. You find new ways to move forward.

“Real artists fail every day.Tweet thisTweet

Build a community

When I started blogging years ago, I was chasing numbers, not people. I thought like a pollster, not someone starting a conversation. And ultimately, I failed.

If you fall out of love with audience approval and embrace your craft, something amazing will probably happen: people will be attracted to your work. They can’t help it; passion is contagious. They’ll want to hear what you have to say.

But you need more than an audience. You need a community. Here are three relationships worth building:

Find your true fans. When you start writing for the love of it, you’ll gain people’s attention. But what you do next is what matters. In order to keep an audience, you need to help people. One way to do this is to give something away for free. This will build trust and extend your reach. And it’s a whole lot of fun.

Earn patrons. These are mentors and advocates who will help you succeed. For Tim Ferriss, it was Robert Scoble. For J.K. Rowling, it was the little girl who convinced her father to publish a book about wizards and witches. For me, it was Michael Hyatt and others. This won’t just happen; you’ll have to be bold and ask. However, if you’re doing great work, people will find it hard to say no.

Make friends. As your fans increase, you may even make a few real friends in the process. Not just followers, but genuine companions. This is the most fun part — getting to be part of someone’s story. Friends will help you even when you don’t ask for it. They’ll hold you accountable. And you will thank them for it.

Of course, I can’t really tell you how to fall in love. I can only tell you how it happened for me. But if you decide to pursue passion and write for the love of it, I would love to hear about it.

More than anything, remember that writing is an illustration of life. Art, as Stephen King says, is a support system for life, not the other way around. So the best way to write inspiring stuff is to live an inspired life.

“The best way to write inspiring stuff is to live an inspired life.Tweet thisTweet

A final challenge

The world doesn’t need more safe writing. Write something dangerous, something that challenges the status quo. Something that moves you (maybe it will move others, too). Then, no matter how scared you are, share it.

If you post it online, share the link. I hope to hear from you.

Get the attention your work deserves and connect with other writers at Tribe Conference. Early bird prices expire this week. Get your tickets now!

What’s your love story? Share in the comments.

February 7, 2017

Here’s How I Really Launched a Bestseller (and How You Can Do the Same)

Two years ago, I launched The Art of Work, and it went on to sell over 50,000 copies in the first year. I wrote about how it became a bestseller here, but I omitted one crucial element until now.

I told you everything that I did to launch The Art of Work and sell over 15,500 copies before it even hit the street. I told you about podcasts. I told you about guest posts. I told you about social media and speaking gigs and all kinds of other things that we think make a book a bestseller.

But the one thing I didn’t tell you was this:

If I got rid of 80% of what I did and only focused on three things, the book still would’ve sold 50,000 copies. And in this post, I’m going to tell you what those three things are and how you, too, can launch a best-selling book.

It took me years to learn this. I didn’t even realize it when I was launching a bestseller. I thought I was just hustling and getting a little lucky. The truth was far more simple.

All you need to launch a best-selling book are three things. Let’s explore the first…

The secret weapon behind nearly every best-selling book (you need an email list)

When I first started writing, I reached out to Tim Grahl, who was a growing authority in the book marketing world, and I asked his advice.

“Tim,” I said. “I want to sell more books. How do I do that?”

“Well,” he said, “how much are you emailing your list about it?”

“No,” I said. “Tim, you’re not listening to me. I want to sell more books. We’re not talking about marketing an online course or something. I need publicity. I need end caps at Barnes and Noble. I need to be on Oprah. Can you get me on Oprah?”

“No,” he said. “You just need email.”

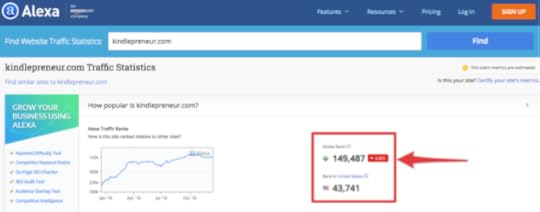

I mentioned this a couple weeks ago when I told you why every author needs an email list. That’s still true.

Having an email list is the most important asset a modern writer can have.

Why?

Because it gives you instant and immediate access to your audience with the push of a button. An email list is like money in the bank for an author. You keep making investments (i.e. subscribers) until one day you want to make a withdrawal (book launch). And if you invest more than you withdraw, you’ll always have money. You’ll always be in control of your success.

But most writers overlook this, and they pay dearly for it. If you want to launch a best-selling book, you’re going to need an email list. That’s the first thing.

But as I mentioned, there are two other things you need…

No one succeeds alone (you need a network)

The second thing you need to launch a best-selling book is a network of people who can talk about your book for you. This includes:

Podcasts

Guest posts

Friends’ email lists

Launch teams

If I had to launch a book tomorrow with zero budget, and all I had was my laptop, I would just start emailing all my friends, and ask them to share the book.

Word of mouth is still the most powerful way to get a book to sell and spread, but the truth is you can help people talk about your work.

How do you do this?

You ask them.

Novel concept, I know But it works. You ask your friends to read the book and share. You ask them to write a review. You ask them to email everyone they know. And when you do this, most people respond. And when you don’t, they don’t.

It doesn’t just happen (you need a plan)

The last thing you need is a plan of action. For The Art of Work, our plan was fairly simple. There were a lot of bells and whistles to it, but at its essence, we were trying to do just two things:

Tell everyone on my email list about the book.

Ask everyone I knew to do the same.

This meant that I strategically picked about ten influencers whom I knew had larger email lists, and I asked them 90 days before the book came out to share it with their audiences. Some said no, but many said yes.

And 90 days later, I had sold 15,500 copies before the book had even hit the shelves. It became an instant bestseller, meaning the first week it released it was on the USA Today, Publisher’s Weekly, and Washington Post bestsellers lists.

How did this happen?

We had a plan. It was simple, but the things we had to do every week were not simple. There were a lot of elements to remember. Even though people were talking about the book, we had to remind them when to say what.

And the only way this was possible was with a master document of everything my team and I were doing, along with a schedule of what to do next and when.

You’ll need the same. Which is why I’m hosting a free, live training this week with Bryan Harris about how to create your own book launch plan. Grab your seat here.

Focus on what will give you the biggest bang for your buck

But what about social media and all that?

As I mentioned at the beginning of this article, I learned all this stuff after the fact. I didn’t realize a book launch could be simple, but also strategic. I didn’t know that 20% of what we did brought about 80% of the results.

But after sitting down and looking at the numbers, I was surprised:

Roughly 500 books were sold through Facebook ads and other social media networks.

The other 15,000 preorders came in from my email list (about 7500) and other people’s email lists (another 7500).

This is how you launch a bestseller. You create strategic relationships with the right people. You harness the power of email marketing. And follow a proven plan.

If you want my exact plan for how I launched a bestseller, along with checklists and a calendar to guide you, join me for a free live training this week for an opportunity to get it.

Click here to register for the webinar with Bryan and me.

How did your last book launch go? What do you wish you knew before you started? Share in the comments

February 6, 2017

What It Takes to Become a Real Artist

“Taco leg!” my son screamed while I carried him wrapped in a towel to his bed after his bubble bath.

“Taco leg?” I asked Aiden, repeating the term just to make sure I heard him correctly.

“A taco leg,” he said matter of factly, “is a taco that has one leg on the bottom.”

Of course. Makes sense. Why didn’t I think of that?

As Aiden got ready for bed, something dawned on me. My son is the most creative he’s ever been. At nearly four years old, he makes up songs and stories all day long. He dances like no one’s watching.

And believe me, everyone is watching.

Just the other night, while we were eating dinner, he started singing this song:

“Feel the day. Feel the day. Feel, feel, feel the day. Can you feel the day? Grow and rain. Sprinkle and feel the day. Daddy, this is called ‘Feel the day.’ It’s a song about when Jesus goes up in the sky and drops popsicles on the ground and people lick them.”

Huh. Okay, then.

An anchorman is born

As a child, I, too, made up things. Stories. Songs. Plays. You name it. I was constantly creating. Most kids do. Recently, I thought back to seventh grade home room.

Our teacher, Mrs. Frankl, would have us students rotate every day, taking turns to share the news with the rest of the class. The night before, you would watch the news, take notes on the major events and weather, and then share that report the next morning in class. I suppose it was an attempt to raise good news-watching citizens, but I didn’t see it that way.

When Mrs. Frankl asked me to read the news, I saw it as an opportunity to break a few rules.

So I borrowed my dad’s video camera, put on one of his ties, slicked my hair back, and gave the performance of a lifetime. The next day, my teacher and friends were taken aback when instead of reading a piece of paper, I pulled out a VHS and popped it into the VCR.

One time, I used a rather, shall we say, abstract drawing from my six-year-old sister and pretended it was a weather map. Another time, I played multiple characters. Each and every time, it was new, which was what I loved about it.

How not to change the world

I’ve retained some of my theatrical tendencies over the years, but many have fallen away—not simply due to lack of practice but out of fear of judgment.

I am afraid about this for Aiden. Soon, he might be too afraid to making things up on the spot. Soon, he might be ridiculed at school for spontaneously singing or moving his body to the beat. He might stop telling stories or making up words. And that’s when he will have to learn an important rule:

You don’t change the world by following the rules.

If you want to make anything significant, you must challenge the status quo. You must embrace being a misfit, at least temporarily, if you endeavor to make anything original and useful.

The process of becoming an artist begins with embracing the things that make us stand out.

“You don’t change the world by following the rules.Tweet thisTweet

Band of misfits

Let’s be honest. Everyone is a misfit at something — particularly in youth. In our youth, we often embrace these traits but shun them as we get older. They may be our sensitivities or special abilities or certain areas of interest — anything that makes us different or unique.

We tend to avoid these things, because most attention leads to shame and embarrassment. So, we blend in, not just for a few insignificant years of pre-adolescence but sometimes for the rest of our lives.

This is the way of the old rules of creativity, which were designed to keep you in line, to make you fit in. But sometimes, these are the very things that will make you more creative. Consider, for a moment, this question:

What if whatever you thought held you back was the very means to success?

Being a misfit, at times, can be a gift. Or it least it can be. I don’t mean to mitigate the pain or struggle not fitting in can cause.

Don’t let shame stop you

For much of my youth, I was picked on, beat up, and ostracized. I had few friends and often dreaded going to school. But there is an advantage to being an outcast. It affords you the opportunity to buck the status quo, avoid the road most traveled, and do what must be done.

That’s what I hope my son learns as he gets older, or at least doesn’t forget. But Aiden isn’t the only one we should be concerned about.

At some point, we’ve all been shamed into not sharing our gifts with the world. We’ve all been told what we have to contribute doesn’t matter and won’t pay the bills. We’ve all considered sticking with careers we don’t love because they’re outwardly successful.

But I don’t buy any of that anymore. I believe in something better, a future where my son can be himself and won’t be asked to conform and be something he is a not. A world free of the old rules and filled with taco legs.

“Being an outcast gives you a chance to buck the system.Tweet thisTweet

What does it take to become an artist?

First, you have to embrace the fact that, in some way, you are a misfit.

Second, start seeing the things that make you stand out as assets instead of as liabilities.

Third, use what you tend to think as your biggest disadvantages and start leveraging those as advantages.

Do those things and you will stand out. You will be weird. And you will be on your way to becoming an artist.

How did you embrace creativity as a kid? What do you need to see differently to become the artists you used to be? Share in the comments.

February 1, 2017

140: Stop Starving and Start Making a Living from Your Art: Interview with Cory Huff

There’s a secret group of talented artists who make small fortunes from their craft. They are full-time writers, painters, and artisans while some of us hustle in the margins of our busy lives unnoticed. Odds are you’ve never heard of them, and the funny thing is, they don’t care. But you should.

At some point in our history, it became unsavory to make a good living from your art. Indie bands that sign with a label are “sellouts” and painters who distribute their canvases on Etsy aren’t “legitimate”.

This is absolutely ridiculous! Isn’t that the aim of professional artists? To obtain the freedom to step away from cubicle day jobs and dedicate their time to impacting people’s lives with their craft?

This week’s guest on The Portfolio Life teaches people how to make a living from their art by rejecting myths, circumventing gatekeepers, and learning how to run their own business.

Listen in as Cory Huff and I talk about the intersection of creativity and money, and why the system we subject ourselves to failed Van Gogh.

Listen to the podcast

To listen to the show, click the player below (If you’re reading this via email, please click here).

Show highlights

In this episode, Cory and I discuss:

The untapped potential of operating outside the system

What it really means to pick yourself

Rejecting fame in exchange for a quiet fortune

If it’s possible for any artist to make a living off of their creativity

The reason stage actors don’t make tons of money

Why books, movies, and prints are more scalable creative products

How failure is just a learning experience

What to say to skeptics

Quotes and takeaways

Not every form of artistic expression is commercially viable.

Every artist has failed ideas.

There are a lot of authors who are terrible and still get book deals.

Gatekeepers can grant legitimacy because we allow them to grant legitimacy.

Fame does not equal money.

Having a successful online business gives me the freedom to pour myself more into the creative side of things without worrying about how to sell it.

“Real artists actually make art and run their business.Tweet thisTweet

Resources

TheAbundantArtist.com

Show Your Work by Austin Kleon

The Gift by Lewis Hyde

The Art of Asking by Amanda Palmer

The Myth of the Starving Artist (Cory’s guest post for Ramit Sethi)

Given the choice, would you rather have fame or fortune? What would it mean to you to make a living from your creative work? Share in the comments

Click here to download a free PDF of the complete interview transcript or scroll down to read it below.

EPISODE 140

That’s a little bit unfortunate, because that system failed Van Gogh, right? He did not make a living from his work while he was alive, but he was a genius. How many other artists out there, who are unrecognized geniuses, are in that same position? How many of them are dying alone of an infection in a house in the middle of nowhere, because they didn’t get picked by one of the big gallery owners? —Cory Huff

[INTRODUCTION]

[0:00:34.9] JG: Welcome to the Portfolio Life. I’m Jeff Goins. This is a show that helps you pursue work that matters, make a difference with your art and discover your true voice. I’m your host, and I want to help you find, develop, and live out your own creative callings, so that you, too, can live a Portfolio Life.

Let’s get started.

[INTERVIEW]

[0:00:51.9] JG: Cory, welcome to the show.

[0:00:54.0] CH: Thanks for having me, Jeff.

[0:00:56.4] JG: I don’t know a ton about you. I have heard of you here and there on the Internet, but here’s how I found you: I Googled the term “starving artist,” and I found this starving artist myth at Google. I found this guest post that you wrote for Ramit Sethi and Iwillteachyoutoberich.com. I started poking around, and then I found your website, Abundant Artist, theabundantartist.com, and I looked at your face on this website, maybe like, your little Facebook icon or something, and I go, “I know that guy!”

I went back to Twitter and I found you, and we were following each other. It was this sort of an interesting — I didn’t know you, but then I knew you, and then this is interesting. I want to start there, if we could, with this idea of the starving artist. I am a writer. You teach people how to make a living as an artist, and this is something that I hear a lot of writers, a lot of creatives, a lot of musicians — I live in Nashville — I hear a lot of people say, “Well, I can never make money doing that,” or “I couldn’t make a full-time living off of that,” and you take issue with this statement, is that fair?

[0:02:11.1] CH: I do, I don’t buy the premise.

[0:02:12.6] JG: Let’s talk a little bit about that. Why do you think that being a starving artist is a myth?

[0:02:17.2] CH: Well, when I graduated from college — I went to art school and I went to theater school, I have a BFA in theater, in acting. By the time I graduated, I had met a lot of actors. I realized that the way that other actors and the other artists that I knew, the ones I knew who were successful, they were doing things completely differently from the way that everybody else was doing it. Like, the way they teach you how to do it in art school, and the way that everybody thinks they know how to do it, right?

I was chewing on that for a while, thinking about, “Okay, well what am I going to do? How am I going to build my career?” and I got a survival job working at this internet marketing agency, and I knew what blogging was back in the day, and so I guess that was enough qualification.

[0:03:01.2] JG: Back in the day, that probably was.

[0:03:03.2] CH: Yeah. I’m selling internet marketing services, and building my creative career, and I started reaching out to these other artists that I knew, and started interviewing them and saying, “How did you make a living from your work?” People were kind enough to share their experiences with me, so I started blogging about that. I started blogging about the intersection of creativity and money, and that was about six, seven years ago.

Just started sharing those experiences with people, and I was also using my internet marketing chops that I was acquiring to get people out for my shows, and get people out to my friend’s shows, and basically it just sort of snowballed from there. I started meeting more and more artists who were like, “Yeah, I’ve been making a six-figure income for my work for 10 years, but nobody knows who I am.”

I started meeting more and more of these artists, and people started asking me to teach classes and stuff, and I think I shared this on Ramit’s blog, the story about Henri Murger from France, and he wrote this — the idea of the starving artist becomes this, it has become this big idea that everybody seems to buy in to, but I’m sure if it’s been that way for that long.

Henri Murger wrote this book in the early 1800’s called A Day in the Life of the Bohemian, is the English translation, and that book went on to inspire a play, which went on to inspire the opera by Puccini, La boheme, which then became the musical Rent, right?

The book is all about these starving artists that live in the student quarter in Paris, and they’re all getting up every day and they’re talking about how they’re not appreciated for their genius, and all that kind of stuff, and they all die poor, right?

If you read closely in the book, what you realize is they don’t actually do anything. They’re not actually serious about making art. They’re not actually serious about marketing themselves or running their business, as it were. These guys all die, and Henri Murger, in the preface to the book, he says like, “Being a bohemian is okay, but it’s a stage of life. It’s a stage in your artistic career, and eventually you have to either become a professional, or you will die,” right?

There’s all these cultural clues that I see, that I say the way that we think about art and money is wrong. The artists who have it figured out, they’re so busy delivering the work that they’re making to the people who have paid them for it that they’re not just taking the time to turn around and teach others about it. There’s this secret underground, there’s hundreds of artists who make a living from their work who nobody knows about, or at least there are very small circle who knows about.

[0:05:38.8] JG: You said, you know, you were using internet marketing, or you were using what you were learning to get people out to your shows. Those were art shows, plays, what were you talking about?

[0:05:47.4] CH: Yeah, originally it was plays. I’m an actor, I do Shakespeare and that kind of stuff. Getting people out to those shows, and then when I started helping my other artist friends, it was art gallery openings, private shows at private houses, and art café showings for art, and all that kind of stuff.

[0:06:05.4] JG: Cory, I’m going to play devil’s advocate here, because I get this flack a lot when I tell people, “You know, you could make a living off of writing.” In fact, now it just might be the best time to be a writer, because of the opportunities to reach people with a blog, and I imagine, although I’m not sure, that similar things could be said of more conventional artists or visual artists.

But people push back and say, “Is there a way to make a living writing without just like, selling online courses and information products to other writers?” You’re doing some of that yourself, and so how do you respond to that?

[0:06:43.1] CH: Yeah, I’m a member of this Facebook group, it’s a private Facebook group for self-published authors, and there’s people in there who write fiction books who are selling $200,000 – $300,000 worth of books in a year self-published, right? They have, basically they have their legion of fans, which isn’t that big, right?

They’ve got a few thousand people who buy their books, and they would never get picked up by a major publisher because they’ve only got 5,000 fans, but those 5,000 fans buy every book they put out. They make a great living doing what they do, but they’re not famous and nobody knows who they are, and there’s dozens of people in that little private Facebook group, too.

My buddy, Matt, lives here in Portland. He’s a sculptor. He makes mobiles. Big, hanging sculptures, right? They’re 30, 40 foot across, huge pieces, and he started out selling these pieces on eBay, He was an oil pipeline engineer when he got started. He got really into Calder’s work, and you know, Alexander Calder’s sculptures, and he just started making stuff that he was inspired by and selling it on eBay. Where other artists would go and try to find art galleries to show their work, he was like, “Well, I don’t know, the easiest thing seems like to sell it on eBay.”

He started selling on eBay, which turned into building his own website and selling it that way, and now his pieces are in all these amazing private collections all over the world, and he’s been featured in every art and design magazine. He’s never shown his work in a gallery.

[0:08:12.6] JG: That’s interesting, because I think that one of the objections to this line of thinking that I hear is using the internet to sell art. Whether it’s fiction, or painting, or what have you. That’s kind of low-brow, right? You can make money off of it, but it’s not going to be great, and I still run into a fair amount of people, especially in the literary world. You say, “Look, you’ve got to get picked up by one of the – now, the big five New York publishers to create anything of lasting value.”

There’s still, I think, a decent contingent of people who are saying you can’t be taken seriously unless you jump through this hoops or satisfy these gatekeepers. I think there’s like, decent historical precedent for that, and there is a lot of crappy art out there that some of these people are making a living.

I’m sure you teach these people. You coach people and teach online classes, you have a conference, and you’re an author yourself, you’ve got a book coming out. I imagine you hear that this kind of objection as well. “I want to do great work, I don’t want to become a marketer, and I want my work to be taken seriously, but also don’t want to starve.” What do you do with that?

[0:09:29.1] CH: There’s so much there.

[0:09:29.5] JG: Yeah, it’s a big question. I just asked you every question you’ve ever been asked. Answer the gatekeeper thing first. That thing about your friend was really interesting to me.

[0:09:39.5] CH: Yeah, the gatekeeper, we have built a structure around art, right? I’ll just talk about fine arts specifically, because that’s what I know. We built a structure where artists somewhere along the line in recent history, we started putting artists on a pedestal. We started saying artists are this — they channel the spiritual world, and they have these ideas that other people don’t have, and therefore we should exalt them in some way.

I think there’s a certain amount of value in that. I do think that we have to honor the visionaries and the artists, but what happened is a bunch of people saw an opportunity to make money out of that.

[0:10:16.0] JG: Yeah.

[0:10:16.6] CH: These gallery owners, they basically, they got a bunch of artist together and they said, “You know what? We’ll pay you guys to make some art, and we’ll go sell that art, and we’ll create a stable of artists whose work we sell.” The interesting thing about that is, in that kind of system, the person that benefits most is the gallery owner, not the artist, right?

The artist gets 50% of the sale price for their work. The gallery owner gets 50% of every artist’s work, and if the gallery owner doesn’t like the artist, he can drop the artist and the artist is out of luck, but the gallery owner still has a bunch of other artists that they can sell from.

That system works for a lot of artists, because the gallery owners, because of their influence and their money. They can go to the newspaper, and they have the resources to go hire a PR team, or go to the newspaper and say, “Here’s the next big artist,” right? There’s all these conflicts going on right now where the large art galleries are, on the right hand, they are donating huge sums of money to the MoMA, or the big museums. Then on the left hand, their people are going to the independent curators that work at the museums and saying, “Here’s the next big artist, you should put on a show for that artist.”

There’s a huge conflict of interest, right? Where the galleries, and the auction houses, and these people who run the money system for the art world are building up a structure that benefits them, and then they get to pick which artist is the artist that makes it, right? The only reason that — we’re essentially all following this handful of taste makers.

[0:11:53.2] JG: Yeah, right.

[0:11:53.9] CH: We’re saying, “Okay, we’re going to give these gallery owners and these auction houses the authority to decide what the most important art is.” That’s a little bit unfortunate, because that system failed Van Gogh, right? He did not make a living from his work while he was alive, but he was a genius. How many other artists out there, who are unrecognized geniuses, are in that same position? How many of them are dying alone of an infection, in a house in the middle of nowhere, because they didn’t get picked by one of the big gallery owners?

Click here to download a free PDF of the complete interview transcript or scroll down to continue reading it below.

[0:12:28.7] JG: What do we do? What’s the alternative?

[0:12:29.7] CH: Well, the alternative is you go outside the system. The alternative is you build up your own audience base, you build up your own clientele. I think that there are a growing number of artists who are going to become influential and whose work will last for a long time, and they operate outside of that system. The one that comes to mind immediately is Amanda Palmer. She is a musician, but she’s also a performance artist, and she does all these other things. Amanda’s book was so fun to read, because she was making a living form her work before she got picked up by Roadrunner Records.

[0:13:06.9] JG: Right.

[0:13:08.8] CH: Then Roadrunner came along, and it was a bad deal for her, and she figured out a way to get out of it, and her career has just exploded since then. She’s so huge, and her work is immensely influential. She’s inspiring thousands of people everywhere. Time will tell whether or not she is influential and whether or not her work retains value, but I think that she is a great example for artists and creatives who are trying to make good work, great work, work that matters, and also trying to give it all their all.

[0:13:41.7] JG: Help me understand the story, because you’re an actor, you are trying to figure out what it took to make a living, you started asking people. You started getting surprised by what you heard, because you found some people who are actually making a good living off of their art, and you started this website telling people stories.

What happened for you? Was it just sort of this gradual understanding that you don’t have to starve to be an artist? Did you immediately start seeing a response? When you started applying what you were learning at your internet marketing job to your art career, can you connect those dots for me a little bit better?

[0:14:16.4] CH: Sure. I think that there’s art that is commercially viable, that can turn into something that makes a lot of money, and then there’s art that doesn’t make a lot of money, sort of inherent to what it is, right? I personally love doing Shakespeare. I do a lot of plays to very small audiences here in Portland. It’s very fulfilling for me, I enjoy doing it, but I’m never going to make a lot of money doing Shakespeare for small audiences in Portland, Oregon.

I had a choice. I could either go continue doing what I was doing, or go into film and start doing a lot of commercial work, and I could start doing a lot of commercials and making money that way.

[0:14:58.0] JG: As an actor?

[0:14:59.3] CH: As an actor, yeah. I just decided I didn’t want to do that. I started looking around. “Okay, how can I use the skills I have, the marketing skills I have to get people out to my shows, but also to help my fellow artists?” Then, it became, “Okay, I just started sharing these stories. You’ve got a choice. You can learn how to market yourself, learn how to run a business like these other artists have, or you can continue doing what you’re doing, and if you enjoy that, great. That’s where I’m at.”

Then, as I started teaching marketing to these other artists that I was working with, words started to gradually grow, kids started asking me to teach online classes instead of teaching one-on-one. At some point, I realized I had like 3,000 people on my mailing list, and I thought, “Wow, if I packaged up an online class and started teaching it, what would happen?”

I started doing that, and it has gradually snowballed. Like, it’s not been like a big blow up or anything like that. It grows a little bit each year, and every time we help an artist be able to quit their day job, because their work is commercially viable and they have learned how to sell it, then I get so much satisfaction out of that. Eventually, I just decided that I wanted to keep doing this, and keep acting as my form of artistic expression, but I don’t have to worry about making money from it.

[0:16:17.6] JG: That’s interesting. I feel like I’m saying that a lot, but it is interesting. Are you familiar with Lewis Hyde’s The Gift?

[0:16:23.7] CH: Yes.

[0:16:25.1] JG: That’s sort of like the classic book that’s hard to read. I recommend it to people and they’re like, “You know, you didn’t tell me about the 150 pages of anthropology.” That’s sort of practical application. The basic idea of that book, you know, is that art and like, the art economy, the gift economy calls it — like the market economy, they don’t connect. The art economy is about giving gifts without expecting anything in compensation. The market economy is about meeting a demand.

As you said, I thought it was interesting, because I hear some people in this, we call it the abundant artist camp, saying like, “You can totally make a living being creative and doing artistic things, and you know, you’ve just got to figure out how to do it.” I like that you’re acknowledging that no, there are some things that are obviously more commercially viable than others.

I guess like, is it possible for any artist to make a living off of their creativity? And if so, what does it take to do that? Because from what I’m hearing, doing Shakespeare in the park isn’t necessarily going to cut it, or perhaps not going to provide the same way as teaching other artists. How do you manage that tension? I hear people saying, “No, that works for you, but it doesn’t work for me.” Do you buy that?

[0:17:41.3] CH: You know, if I’m honest, I have to say that not every form of artistic expression is commercially viable. I think that’s true. I look at a lot of art, and see a lot of stuff that is political in nature, right? Its goal is to move people to make a political choice. It’s very difficult to sell political work. You might get a sponsor or something who wants to sponsor the artist because they believe in that artist’s message, but as far as a commercial venture, that’s very difficult.

Doing Shakespeare in the park is commercially very difficult. I know a number of actors who, they do that kind of stuff, and they make their living doing commercials. Or they teach acting to other actors, or they direct. Most stage actors don’t make a living solely from performing on stage, and that includes actors all the way up to and including actors on Broadway.

Most Broadway actors, because they’re living in New York, they might get a salary on Broadway, but more than half of it goes to rent, right? It’s the function, it’s this intersection between commercial viability, between distribution, and your salary versus your costs, right? If I made Broadway salaries in Portland, I would probably have a very different career right now.

You know, that’s a different thing. I think that, let’s talk about distribution for a second. Like, the reason stage actors don’t make very much money is because only so many people can see a play at a time. The cost of putting on a live play is tremendous compared to — you can only charge so much. $300 tickets to Hamilton are awesome, but you can’t charge a ton more than that for very long, because eventually you run out of people that are able and willing to pay that cost.

Seeing a film, right? Like you can show a film to millions of people for $10, $15, and make a ton of money that way, and the same thing happens for books, right? You could sell a ton of books to people at a low price. You can sell a ton of art prints to people and make the money that way. It’s about scalability and distribution.

[0:19:48.5] JG: How do you manage this tension? You and I have similar occupations, we’ll say, where you do creative work that doesn’t necessarily pay the bills, or pay the bills as well as the coaching and teaching side of what you do, and I’m not going to speak for you, but speaking for myself, I like both of them. They’re both really fun.

In some ways, having a successful online business gives me the freedom to, as you were talking about doing Shakespeare, gives me the freedom to pour myself more into the art side of things, creative side of things, than worrying about how am I going to sell this, and in effect, you get to enjoy it more sometimes. For me, writing books, I get to create something that’s more pure, but I’m just speaking for myself, and I’m curious what your experience is.

There’s a trap in the business side of things. You can keep growing the online classes, you could — especially with internet marketing, there’s always a new tactic, something else for you to do. That feels like tension to me. I don’t know what it feels like to you, but I’m wondering how you deal with that?

[0:20:49.7] CH: Yeah, I think that’s certainly true. My film agent kind of gets annoyed with me, because I won’t do commercials. Here in Portland, we get Fred Meyer commercials. Fred Meyer’s based here, so we do Fred Meyer commercials all the time. Probably once a week I’m being asked to do a Fred Meyer commercial, and I always say no, because it’s just not interesting to me and I don’t need the money.

When I tell other actors that I don’t need the money, they get mad at me. On the other hand, I just finished a run of a play, it’s a brand-new world premier play. Nobody had performed it before. I got to originate the character, I got to work with some fellow actors to bring this new piece of theater to life. I would not be able to do that if I were in different circumstances, right?

Yeah, that’s great, but there is certainly a tension. I do spend quite a bit of time on the business side, and I enjoy it. There is the tension between how much time do I get to spend doing theater and how much time do I get to spend on my business, and I’m lucky that for the most part, I get to decide that for myself. Like my circumstances are such that I get to make that decision, and I sort of give myself 20% time. Like one day out of each week is solely on artistic pursuits, right?

Then I also do stuff in the evening and on the weekends with theater. I don’t know, I don’t have a good answer. Those are my thoughts, I guess, but I don’t have an easy solve for that. I think that it’s better than being a waiter while trying to be an actor.

[0:22:17.9] JG: Yeah, that’s a good point. There’s always — the person who is doing it full-time, unless they get some big break or whatever, and maybe even not then, they’re spending their time doing something else, of course.

[0:22:30.4] CH: Yeah. It’s really interesting to me to see — you mentioned maybe not even then. The number of musicians and actors and painters and stuff who buy all outward appearances appear to be doing very well, they’ve got a big book deal, or they just did a big movie. Outward appearances can be deceiving. The money is not necessarily what you think it is.

[0:22:53.2] JG: Totally.

[0:22:54.5] CH: Fame does not equal money.

[0:22:56.0] JG: Yeah, amen to that. One of the wealthiest guys I know quit his record label. He lives in Nashville, actually his record label fired him. He was making like $150,000 a year as a musician, pulling in millions for the record label, but he didn’t understand how many hands were in his pockets, so to speak. Yeah, they fired him because his records stopped selling and he has to figure out how to — book small shows, and sell records online, and do all the stuff, and now he makes millions of dollars a year.

[0:23:29.0] CH: I hear that story so much.

[0:23:31.0] JG: Yeah, nobody has any idea who he is. It’s really interesting. He’s not on the radio anymore, he’s not famous anymore, people don’t’ recognize him in public anymore and he loves it. He’s wealthier than he’s ever been. Speak to the purist in me, and in many creatives. I don’t care about money, I don’t want to learn about business, marketing sucks, can I still make it as an artist? What do you do with those people? You have to encounter those people in the work.

[0:23:56.6] CH: I do, If I’m being thoughtful, my response is usually, “Okay, like I get it, it sucks. I think it sucks sometimes too, but learn enough of it and do it for long enough that you can hire somebody to do it for you. Get your business to the point where you can hire somebody to do the stuff you don’t want to do, because then you retain all the control. You get to make all the artistic decisions, and if you’ve got good people around you, then you don’t have to worry about it.”

[0:24:24.4] JG: Yeah, because the alternative is, like what happened with my friend, where like he didn’t understand all that stuff and they fired him. His record label left him, his manager left him, I mean, he was left in the gutter.

[0:24:37.6] CH: The economy changed in 2007/2008 in the US. It sent a whole bunch of art galleries out of business, right? All these 50, 60, 70 year old artists who had previously been making six-figure incomes with the galleries were completely out of whack. Their sales just disappeared overnight. They came to me and said, “I have no list, I have no idea of who bought my art previously, what do I do?”

I think that there is a lot of — you really have to decide, if you’re going to do a deal with a gallery or a record label or whatever. Make sure you have your eyes open when you go in, and the other thing, going back to legitimacy, the gatekeepers who grant legitimacy, they only grant legitimacy because we allow them to grant legitimacy. We have all decided that this critic or this company knows what’s best for us, and you probably recognize this, like there are a lot of authors who are terrible who get book deals.

[0:25:39.8] JG: You know, what’s interesting about that is I’ve worked with several publishers, I’ve self-published a book, I’ve done kind of both things. Every time, the editor, because I write nonfiction, the editor will tell me, “This is fun, because you’re a writer.” I’m like, “Who else are you working with on books?”

The truth is, lots of famous people who have platforms, who decide I’m going to write a book because I can make money off of that. They’re not writers, they just are speakers or whatever, and they’ve got a message, and then they don’t know how to write a book and…

[0:26:09.2] CH: Yeah, I mean, there’s all this mystery, thriller, mystery and thriller writers who – essentially, they’re book factories, right? They’ve got 20 writers on staff, and they turn out a book every six months or whatever, and I mean, every three months. I’m looking at you, well I won’t say names.

My book is coming out from a major publisher. I’ve got a book coming out from HarperCollins, How to Sell Your Art Online. It comes out in June, and I am amazed at the doors that opened, because I can say, HarperCollins published my book.

[0:26:44.0] JG: Isn’t that interesting?

[0:26:45.2] CH: Yeah, it’s like, all of the information in this book has been elsewhere. You can read my blog, you can read my thoughts there, but because HarperCollins decided that they would pay me in advance to compile all of my thoughts into a book, suddenly it’s more meaningful. I don’t know, but that is changing.

There’s a whole world of people out there who want art, and writing, and music from artists who are outside of the traditional system. There are people who actively seek out self-published authors. Goodreads does amazing, because you got this community of people who are like, “Did you hear about this artist? This writer? They’re so amazing.” People have built their careers on Goodreads, and there’s people out there who go to concerts and they’re looking for bands that are awesome that are not signed.

[0:27:37.6] JG: Yeah, especially with music.

[0:27:40.2] CH: Yeah, these weekend long music festivals where you never heard of any of the musicians and they’re all amazing. There’s a market for that. There’s a market for people who want to buy original art for their walls, and they don’t want to go to a gallery because galleries are intimidating and scary.

[0:27:55.4] JG: Yeah.

[0:27:55.4] CH: I could go on and on.

[0:27:56.8] JG: You have a traditionally published book, but you’re like way into what — I don’t know if this is the right word for it, but like, the Indie Art scene, and you said doors actually opened for you, working with big New York publisher. I’ve seen similar things. I’ve kind of danced between independent work and working with so-called gatekeepers, and sometimes I’m like, “this is great,” other times I’m like, “what is the point of this?” Did you struggle with that decision to self-publish this book or work with a traditional publisher? Where did you land on all that?

[0:28:26.5] CH: Yeah, I really did struggle with it. I think that I would actually have made more money if I self-published the book.

[0:28:31.4] JG: Yeah.

[0:28:31.4] CH: I ran the numbers, and just based on my own mailing list, if I had self-published the book, let’s talk about numbers for a second. If I am self-publishing this book, and my own royalty, I guess, for the book is 25% for digital sales and, what is it? 15% of cover price for paperback sales? That equals out to about eight books a book, depending on the price. Not eight bucks, a couple bucks a book or something like that, depending on the price.

With my mailing list and the number of people on my list, I could, if I sold one book to each person on my mailing list right now, I would make more money than I made in my advance. It’s really interesting to try to make that decision. What’s my goal with the book? Is it to make money, or is it to grow my influence?

I opted to go with grow my influence, because the publishers do have that kind of influence, and I can get my book into all the bookstores and all that kind of stuff, and the art world that is so tethered to academia and to the gatekeepers, this book will now open doors for me for art organizations that previously wouldn’t give me the time of day.

[0:29:39.0] JG: Interesting. Are you seeing that already?

[0:29:41.0] CH: Yeah. I’ve got speaking opportunities that have come up because I said I had a book. Yeah.

[0:29:48.2] JG: What I hear you saying, Cory, is like, there’s no answer. There’s no one answer. It’s a little bit messy, and it sounds like there’s opportunity to make a living off of your art, off of your creative gift, as long as you’re willing to do some of the work, but at the same time, you’re not like saying, “Well screw all these 500-year old systems, like the printing press for example.” It sounds like you have sort of a blended approach. I mean, is that true?

[0:30:15.6] CH: Yeah, I’ve tried to. I try to look at each opportunity and each problem and say, “This is my tool box. What do I do? What makes the best choice, or what outcome do I want to have?” I don’t think we need to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Like you don’t have to go all independent, and ignore all of the other opportunities, but I think that the great thing about the internet, at least as it is right now, is that it opened up more options for creative people.

[0:30:45.3] JG: Here’s a question, just point-blank. Do artists have any legitimate excuse nowadays to not make a living off of their art? If they’re willing to do the work?

[0:30:56.2] CH: Assuming that your work is at least somewhat commercially viable, and you know, I do not know every time whether or not a piece of work is commercially viable. I saw a woman making lace doily’s with swear words in them.

[0:31:12.4] JG: Was this in Portland? I feel like it’s in Portland.

[0:31:15.4] CH: I don’t remember where it was. She was in a program that I was in, and it looked like the doily that you would see on your grandma’s table.

[0:31:23.1] JG: Like your nasty grandma, apparently.

[0:31:25.8] CH: Yes. Just a big old F bomb in it. You know, she sold them. Whatever. I don’t know what’s commercially viable. I feel like there is a niche for every kind of weird art, and some of those niches are bigger than others. There is a group of people who are into whatever weird thing that you’re into, right?

As an artist, I think you can find them, I think that you can make them an offer and see if they respond to it. I think that you can be dedicated in following up, in building those relationships. I can’t say 100% that every artist will make a living from their work, but I can say that it’s a lot more possible than people make it out to be.

Every time I talk to, every time I get an email from an artist, more specially from a young person who is in college, I get an email that says, “My parents made me study engineering because that’s a solid career,” it just kills me a little, because I know so many artists who make more money than an engineer ever will.

It’s just — I look at it like entrepreneurship, right? Small businesses are the engine of the economy, and everybody, so many people start small businesses. I don’t think it’s that different from any other small business that’s getting started.

[0:32:49.0] JG: Yeah. Gosh Cory, you’re just being honest here, which I love. You know, you’re not overstating something or being hyperbolic, but I love that you said that there’s more opportunity than there has ever been. I’m imagining somebody listening to this going, yeah, I’m one of those people where my work isn’t commercially viable, but you said, I don’t know when that happens. If you’re feeling that way, is the best thing for you to do to go find that niche, put your work out there and just see? If people don’t connect with it then you know versus just assuming they don’t.

[0:33:20.5] CH: Yeah, absolutely. Straight up steal Austin Kleon’s book title, Show Your Work, right? Just go show your work, and what I’ve seen with artists is most of them are too afraid of showing their work. They say, “My work is not commercially viable,” and usually, they’ve shown their work to a few dozen people at most.

[0:33:42.3] JG: Yeah, wow.

[0:33:43.4] CH: They haven’t really done the work to figure out like, who would potentially be interested in that kind of stuff? Who is going to be interested in doilies with swear words in them?

[0:33:53.2] JG: Nasty Nana.

[0:33:54.3] CH: I don’t know, do you sell those as Hot Topic? I have no idea. There’s somebody out there who likes it, and there’s so many weird online communities. You owe it to yourself to at least give it a try.

[0:34:05.7] JG: Then if you fail, then what do you do? You just move on to something else?

[0:34:09.5] CH: Yeah, you move on to something else, you know? Every artist has failed ideas. Every artist has a bunch of work that’s really sucked, that they burned, right? Every entrepreneur — I started three other businesses before I started this one, and they all failed. People who, like failure is just a learning experience and you just move on to the next thing.

[0:34:28.6] JG: Cory, thanks so much for your time.

[0:34:30.8] CH: Thanks so much, Jeff.

[END OF INTERVIEW]

They make a great living doing what they do, but they’re not famous and nobody knows who they are. —Cory Huff

Click here to download a free PDF of the complete interview transcript.

January 30, 2017

Stop Running the Wrong Race and Choose Your Own Craft

It’s demotivating to run a race and see everyone pulling ahead of you. I know because I’ve been there.

Recently, a friend shared with me a time when he was running a marathon and watching all these people pass him. He was frustrated, because he thought he was in good shape, but here he was, struggling to keep up with the pack.

Just as my friend was on the verge of calling it quits, someone came alongside him and said, “Run your own race.”

The curse of talented friends

Sometimes, I find myself despairing of my lack of abilities in certain areas. This is exacerbated by the fact that I know so many talented people.

For instance, I’m not as good a leader as Michael Hyatt or as good a marketer as Bryan Harris. I’m nowhere near as funny or as clever as Jon Acuff, and I wish I could write half as well as Ally Fallon does.

I remember one day, walking across the street while headed to my office thinking these things, wondering how I could possibly ever catch up the amazing abilities of my friends.

It just seemed so hopeless.

And if this was a game I couldn’t win, then what was the point? As a high achiever, I have to be competing in something I have a chance of winning. Otherwise, I’ll quit. Just ask my wife.

Anytime we break out a board game and I don’t see a clear path towards victory, I give up, saying, “This is a stupid game. Let’s play something else.”

Which really means: Let’s play something I can win.

Winning feels like everything

You can tell me that winning isn’t everything but that doesn’t fully register with a personality like mine. I have to see some kind of path towards success; otherwise, I lose motivation.

And so, while walking across the street that day, I heard a voice interrupt my thoughts, and say, “Don’t beat them at their own game. Beat them at yours.”

I don’t know if that was God or my subconscious or the musician on the street corner. But to whomever the voice belonged, I am grateful. Because it struck a chord.

“Don’t beat them at their own game. Beat them at yours.Tweet thisTweet

Choose your craft

You can spend a lot of time feeling bad about not being successful in one area of life or another. And you can always find something to be bad at. Trust me. I do it often.

The challenge here is to choose your craft. Focus on the thing — or portfolio of things — that only you can do. And do it well, without apology or complaint.

And when you see someone excelling in an area that you would like to succeed at, remind yourself, “That’s not my craft.”

This applies to everything from writing in one genre, like literary fiction, and getting jealous at the success of another author in a completely different genre, like self-help, to feeling bad about not being a great marketer when your calling is something else entirely.

That’s not to say we can’t improve at certain skills we may need to succeed, but it should be a reminder to us that we can’t master everything.

At those times when you feel those twinges of envy, tell yourself, “I have already chosen my craft, and that’s not it.”

After all, you can only run one race at a time.

What is your craft? How can you claim it and avoid getting distracted by someone else’s craft? Share in the comments.

January 27, 2017

3 Keys to Finishing Your Book Once and For All

I work with a lot of writers who write down, either mentally or on paper, their goal to finish a book.

They do so for a lot of reasons—because up to this point finishing their book has been elusive, or because the idea recently took shape in a way it hadn’t before, or because they can’t keep pretending it doesn’t exist.

It does exist, and apparently it’s so vehement about existing, it’s not going away no matter what they do to suppress it.

So they might as well give up and do something about it.

That’s what we writers want to do, I think, if we’re honest. We want to do something about it—something so consistent, so thorough, that on the other side of our doing something we look in the day’s mail and there it is. Finished. Not perfect, certainly, but here. Finally here.

And I think of all the writers who months later begin realizing it’s not going to happen. Not this time. And I think about the pangs of guilt and literal pain they will feel deep in their chests. Another disappointment. Another expenditure of wasted effort. No book.

I don’t want that to happen, and so I’m writing this to help.

Finishing your book once and for all

The purpose of this post is to give you an on-ramp to finishing your book once and for all. As I’ve worked with hundreds of writers over the years and observed my own writing practices, I’ve noticed three things that often comprise the difference between finishing and not finishing.

It just so happens the three initials for these elements are C. P. R., so you can think of this as CPR for your book project if you’d like. If nothing else it makes them easy to remember. The three elements are:

Concept

Process

Retreat

Let’s delve deeper into each.

Key #1: A compelling concept

A compelling book concept is one that promises to meet a need people have in a distinctive way. When you have confidence in your concept, you have that much more motivation to keep writing.

The first step to a great concept is to get really clear on the need your book is addressing. One can do this in many different ways, including good ole Google searches in your topic’s space. You might also try doing a search in BuzzSumo. This will produce a list of the most shared articles related to your topic, which will give you clues to the major pain points of your audience.

Once you have the need you want to address in place, brainstorm a distinctive working title and subtitle, and you’re off to the races. Later in this article I’ll share how to obtain an infographic and video tutorial that will help you further with this process.

Key #2: Design a sustainable writing process

When I first started blogging, one of the best pieces of advice I heard was, “Fall in love with your process.” And another equally good piece of advice (from Jon Acuff) was similar: “In the beginning, measure hustle, not traffic.”

The reality is we have very little control over things like how an agent or publisher responds to a query or proposal. We can’t stop someone from writing a negative review on Amazon. One thing we do have control over is our process.

So what’s your process? When do you write? What are your tools? Do you have a certain word count you’re shooting for each day? And so on.

Design your process, fall in love with it, and stick to it. Below I share how to download a worksheet to help you do this.

Key #3: Schedule a writing retreat

I’ve saved the best for last because this one really is the X factor.

Back in 2013 I had an idea for a short manifesto-style book. I had much of the content development done, but between a full-time job and family commitments, I couldn’t find time to put it all together.

Realizing spring break was coming and our family was planning to stay home during this time, I asked my wife if it would be all right with her if I used that week to finish my book. She said yes, and so each morning found me in front of my laptop at a coffee shop.

Five days later I was well on my way to self-publishing what became Do Your Art: A Manifesto on Rejecting Apathy to Bring Your Best to the World.

Writing retreats happen in all sorts of places and times and manners. The important thing is to schedule and take one, if not several. See below for a free writing retreat planner.

Concept, process, and retreat. Start with these three, stick with them, and you’ll be well on your way to holding your book in your hands.

A special gift for Goins, Writer readers

I’m so grateful for this opportunity to write to Jeff’s audience. I have a lot of respect for him and for anybody who follows his content. In light of this, and because I want to make this CPR process as user-friendly as possible, I’ve developed a sequence of free videos and worksheets that I call the Finish Your Book! mini-course.

Inside you’ll find:

Seven brief teaching videos

An infographic on how to develop a compelling book concept

A worksheet to help you design your writing process, and

A planner to help you schedule and plan an effective writing retreat

The whole course should take you less than 90 minutes, and at the end of it you’ll be set up to finish your book once and for all. If you’re serious about finishing your book, this course is just what you need (and it’s completely free).

To access it, click here.

Do you have a book in you? Which of these three (C.P.R.) elements would help you the most? Share in the comments.

January 25, 2017

139: Forge a Heroic Path for Your Readers to Follow: Interview with John Sowers

You can spot a man of conviction from a mile away. You take notice when a woman with a fire in her heart enters the room. But these people aren’t self-made. They didn’t reach this point on the path alone. Someone showed them the way.

Mentors are the guide on our own hero’s journey. They share their story so we can learn from their experience. Mentors believe in us so we can believe in ourselves.

This week’s guest on The Portfolio Life was raised by two heroic women and always wanted to be a writer. He wrote a doctoral dissertation on fatherlessness (which was later published by Zondervan), co-founded The Mentoring Project, and even visited The White House to meet with the President.

In this interview, John Sowers and I talk about the critical role of mentors, the four steps of the heroic path, and chasing jaguars in Arizona.

Listen to the podcast

To listen to the show, click the player below (If you’re reading this via email, please click here).

Show highlights

In this episode, John and I discuss:

The correlation between passion and conviction

Knife making and rustic hobbies

Shooting wild animals (with a camera)

Writing about fatherlessness after growing up without a male role model

What would JRR Tolkein say about how the True Myth informs masculinity

The fear he faced after becoming a father

Listening at the edge of your understanding

Quotes and takeaways

“We find courage when we love someone deeply.” -John Sowers

“We find strength when we’re deeply loved.” -John Sowers

Mentoring gives you purpose, direction and opportunity.

“Positive affirmations can change the course of our lives.” – John Sowers

Most great things are borne out of a deep sense of conviction.

Write what needs to be said.

Fatherhood is about saying the things you don’t feel like you need to say.

“You need someone to believe in you before you can believe in yourself.Tweet thisTweet

Resources