Jacqueline Winspear's Blog, page 2

October 13, 2011

Intelligent Economy - Circa 1915

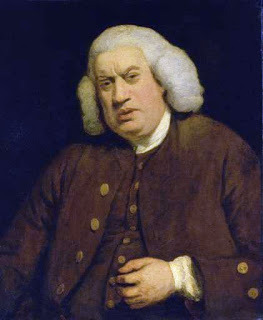

In 1915, the author of an article on "Intelligent Economy" published in Woman's Magazine, a UK periodical - not to be confused with the later Woman magazine - asked the following question: What is economy? She then quoted the following in response: "Laudable Parsimony" (from Dr. Johnson)

He looks laudably parsimonious, doesn't he? Our writer added another quote: "Wise frugality that does not give a life to saving, but that saves lives." (George Crabbe, who has a softer countenance, I think.)

Given the privations suffered on the Home Front during the Great War, it was hardly surprising that the author reveals herself to be a bit ticked off with authority, in a manner that seems more than familiar in the present. Here's what she said:

"Never before has the Board of Trade been so concerned with our private catering as to bid us consume less meat." She goes on to repeat a catalog of advisory notices distributed by various government departments, and as if weighing it all up adds: "In some ways we have been rather startled at the idea of past and unrealized wastefulness on the part of the ordinary consumer. Who among us, for instance, ever gave a thought to the question of whether the nation's supplies of old potatoes were exhausted before we began to demand new ones?"

As an island, Britain depended upon much of her food from overseas – particularly the Empire – and in the Great War U-boat activity curtailed many of those imports, as it did in the Second World War. Niall Ferguson, in his book, The Pity of War, said that WW1 brought the first great age of globalization to an end. And you thought globalization was new? Far from it.

But amid the complaints, there is some intelligence in Intelligent Economy that shines through. Here's one line:

"Do not buy something in a sale because it's cheap."

Oh dear, that would be me. You see, I love a sale. I rarely pay full price for anything, if I can help it, and I just love a bargain. And I have to say, those little red Macy's 20% discount cards have led me astray (especially on the "extra 15% off" days, when you can double-dip the discount), as have the Bed, Bath & Beyond cards that pop into the mailbox so regularly. Did I really need that cherry stoner? Or that chopping board? "You can't use them all at once, can you?" said my husband, wondering if the three-for-$12 set I'd bought at Costco weren't enough for one household.

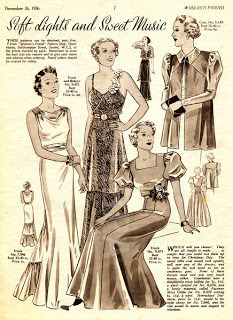

My friend Maria introduced me to her PPW theory some thirty years ago. Maria, by the way, was born in the Netherlands to parents who had suffered deeply during the Second World War. PPW = Price Per Wear. She told me that if you were buying something to wear to work that you would wear day in, day out, and that you wanted to last, then that's where you put your money. That ball you would only ever go to once in a lifetime? No, don't splash out on a gown – that's where you go cheap. Remembering PPW means you will bear in mind that the money you've shelled out on clothing has to pay you back in hours spent on your body!

Just recently we've heard a lot about buying more goods from our home suppliers, rather than from overseas (child labor in China, the trade deficit, the jobs of workers at home on the line – the reasons mount up), but it seems so much more strident when couched in the following terms by our 1915 author:

"'Everything is so dear now,' says the young person who hitherto has bought the lowest price goods, and it will be no bad thing for her if she has to sit down and darn the better hose at 1s 9d or 2s a pair from the English loom, instead of throwing aside the flimsy things at 9d from Austria as soon as holes and ladders appear in them. For in the former case, the money remains in this country benefiting our own people. To make use of the home products as far as possible is one of the soundest works of practical economy that we can exercise at the present time." (the currency is shillings and "old" pence, so two shillings – 2s – would be about 10 pence in today's British currency, and about 6 or 7 cents here in the USA)

But here's an interesting point – the author warns the young women readers not to think their new-found employment – and extra money – will go on forever, and warns them that they will be sent home as soon as the war ends, not simply because the men who have gone to war will be returning to their jobs, but because so many goods (munitions, for example) will not be required. She was right – many women lost their income in this way, but employers also realized that they could pay women less than men – and (surprise, surprise), they did the job just as well!

But one point quite surprised me, in this "two sides of economy's coin" that the author brings to her article – many foods were beginning to be sold pre-packaged instead of being sold "loose" (even when I was a child in the early 1960's, I remember biscuits being sold from big tins – the shop assistant would fill a bag for you – half a pound, for example). And of course, by biscuits I mean cookies. She concludes that the cost to health of not buying pre-packaged goods could be more expensive than the risk of (for example) buying milk from the dipper instead of from a sterilized and sealed bottle. But of course, those bottles were returned for refund in those days.

I think many of us were raised by women who believed that you had no business even thinking of buying something if you couldn't afford it. I remember a saying that was repeated to me, "What's for you will never go by you." I love that one, and to this day, if there's something I see that I think I want, I leave it behind and come back to the store another day (the regretted purchases mentioned previously notwithstanding). Sometimes I realize I didn't want that thing as much as I thought, and there have been occasions when I know I'll be disappointed if the desired "thing" isn't there when I return to the store – but there again, if I've missed it, I wasn't meant to have it anyway, so it passed me by. This process also saves me – most of the time – from falling foul of the need for instant gratification. Mind you, the less said about the Eileen Fisher sale, the better.

Did your mothers and grandmothers have words of wisdom on the subject of Intelligent Economy? My mother, who lived through the Blitz in London, as well as wartime rationing, has a veritable catalog of such advice? (To this day she saves wrappers from butter and margarine to line a cake tin). Or have you read about a cost-cutting measure from past times we could use today? I've a few more of those plain "Secrets" moleskin journals left, so I'll send one each to the first three readers leaving their snippet of advice from the inspiring generation here on the blog (email your mailing address to me via my website – you'll know if you are among the first three to leave a comment). And even if you're not among the first three, we'd all love to hear your comments and timely advice on the subject of Intelligent Economy!

Next time: Profile of a Heroine – or two.

Published on October 13, 2011 13:34

October 5, 2011

More On Downton Abbey - A Blog Exclusive!

This week was supposed to be a post on Intelligent Economy, however, one does have to dance with the moment, and when an exclusive opportunity is offered, as the originator of this blog I reserve the right to veer in a different direction if circumstances suggest a change of plan.

Since starting the blog a mere three weeks ago, I have received emails from several followers who have materials they believe might be of interest to me - I have been amazed by their generosity. You'll hear about them as time goes on. Bryan Webb is one of those readers, and last week he emailed to inform me that he had some photographs of the filming of war scenes for the new series of Downton Abbey that no one else had seen - he was involved in preparing the trenches for filming (correct me if I have that wrong, Bryan). I received those photographs this morning, and a few took my breath away, they were so realistic – when you look at them remember that it's a set and no real horses were harmed in the filming, however, also remember that war is terrible and imagine those scenes multiplied a thousandfold and the dreadful memories that men who came home lived with. But first, a bit about the Khaki Chums.

Long before filming begins on any production, scouts are sent out to find suitable locations. Finding a farmer who doesn't mind his land being churned up to become a battlefield is something of a challenge – despite remuneration offered, having a film crew tramping all over your property is a pain. However, the producers of Downton Abbey must have been thrilled to bits to learn that a ready-made trench was waiting for them – courtesy of a man named Taff Gillingham.

Gillingham is a member of the Khaki Chums, who are not a reenactment group, but a cadre of enthusiasts (authors, historians, collectors) who have a mission to inform the public about the experience of the citizen soldier. In a BBC interview Gillingham said, "First hand experience can teach you stuff that reading a book or watching a film never could … if you can smell it, taste it and feel it, it is a real experience." Bryan Webb is one of the Chums, who were conscripted to bring a realism to war scenes in the new series of Downton Abbey – and he and his wife enjoy my books, which brings us back to the beginning of this post, and I know you are aching to see those photos of the Downton Abbey WW1 set, so here we go:

Here are two photos of dead horses. Hundreds of thousands of horses were killed on the Western Front alone – they suffered devastating wounds from the shelling, were gassed and endured dreadful skin conditions and poor fodder.

Even though it was a "dummy," that black horse with the long mane brought me to tears, reminding me of my own horse, Oliver, a young Friesian – I don't know what I would have done, had I lived then and the men from the army knocked at the door with a requisition notice. If you weep at these photos, then take a big box of Kleenex when you go to see The War Horse, Steven Spielberg's adaptation of Michael Morpugo's terrific book, due to hit the screens later this year.

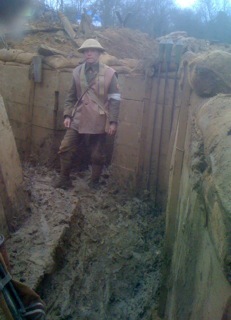

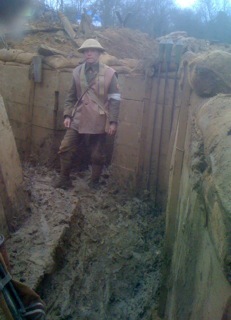

When you read about the Great War, the never-ending mud seems to play a very big part:

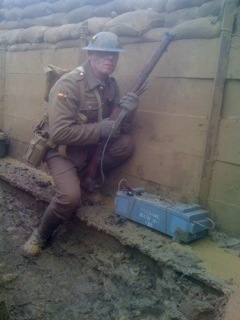

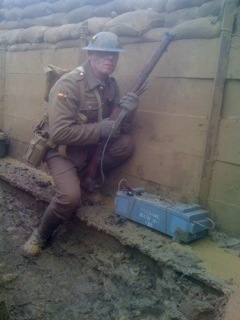

A couple more photos from the set:

And this is Bryan:

Here's what Bryan said about his experience: "Attention to detail on the set was incredible. I spent some time on the set when everyone had gone to lunch and in those quiet moments, my reflection was with those back nearly 100 years ago."

Bryan has also visited the Menin Gate memorial and the battlefields of France and Flanders many times, and comments: "Every time we are at the Menin Gate in Ypres for the Silence, I can feel that loss. Some early mornings on the battlefield, just as the sun comes up, there is an overwhelming sense of peace which contrasts the events we are there to remember."

I took that photograph in Delville Wood, in France. Beneath those warming rays of sunshine the remains of many "missing" British and South African solders have been buried since 1916. This idyllic scene belies the fact that parts of the wood are out of bounds, due to unexploded ordinance that also rests beneath the ground.

The truth is that the population at home had little idea about the truth of battle, or of the everyday lives of the soldiers (much time waiting for battle while waging war with lice in their clothing). They only knew that everyone had to "do their bit." I wonder about that a lot, the fact that today our armies are engaged in war overseas and we understand so little about their true experiences, the pressures, the good times, the horrendous times. And most of us have suffered no deprivation as a result of war. It's important to remember that real soldiers don't pack up and leave the set every day, so I admire Bryan's living history commemorative group, the Khaki Chums, and their mission.

You might be interested in an essay I wrote following my first visit to the battlefields of The Somme and Ypres, in 2004: http://jacquelinewinspear.com/essays-skylarks.php

I'd love to hear your comments on this post (I understand that too many advertisements are really annoying Downton Abbey fans in the UK) and next week – yes, we'll be taking about "Intelligent Economy." I think we all need a bit of that right now!

And thank you again, Bryan.

Since starting the blog a mere three weeks ago, I have received emails from several followers who have materials they believe might be of interest to me - I have been amazed by their generosity. You'll hear about them as time goes on. Bryan Webb is one of those readers, and last week he emailed to inform me that he had some photographs of the filming of war scenes for the new series of Downton Abbey that no one else had seen - he was involved in preparing the trenches for filming (correct me if I have that wrong, Bryan). I received those photographs this morning, and a few took my breath away, they were so realistic – when you look at them remember that it's a set and no real horses were harmed in the filming, however, also remember that war is terrible and imagine those scenes multiplied a thousandfold and the dreadful memories that men who came home lived with. But first, a bit about the Khaki Chums.

Long before filming begins on any production, scouts are sent out to find suitable locations. Finding a farmer who doesn't mind his land being churned up to become a battlefield is something of a challenge – despite remuneration offered, having a film crew tramping all over your property is a pain. However, the producers of Downton Abbey must have been thrilled to bits to learn that a ready-made trench was waiting for them – courtesy of a man named Taff Gillingham.

Gillingham is a member of the Khaki Chums, who are not a reenactment group, but a cadre of enthusiasts (authors, historians, collectors) who have a mission to inform the public about the experience of the citizen soldier. In a BBC interview Gillingham said, "First hand experience can teach you stuff that reading a book or watching a film never could … if you can smell it, taste it and feel it, it is a real experience." Bryan Webb is one of the Chums, who were conscripted to bring a realism to war scenes in the new series of Downton Abbey – and he and his wife enjoy my books, which brings us back to the beginning of this post, and I know you are aching to see those photos of the Downton Abbey WW1 set, so here we go:

Here are two photos of dead horses. Hundreds of thousands of horses were killed on the Western Front alone – they suffered devastating wounds from the shelling, were gassed and endured dreadful skin conditions and poor fodder.

Even though it was a "dummy," that black horse with the long mane brought me to tears, reminding me of my own horse, Oliver, a young Friesian – I don't know what I would have done, had I lived then and the men from the army knocked at the door with a requisition notice. If you weep at these photos, then take a big box of Kleenex when you go to see The War Horse, Steven Spielberg's adaptation of Michael Morpugo's terrific book, due to hit the screens later this year.

When you read about the Great War, the never-ending mud seems to play a very big part:

A couple more photos from the set:

And this is Bryan:

Here's what Bryan said about his experience: "Attention to detail on the set was incredible. I spent some time on the set when everyone had gone to lunch and in those quiet moments, my reflection was with those back nearly 100 years ago."

Bryan has also visited the Menin Gate memorial and the battlefields of France and Flanders many times, and comments: "Every time we are at the Menin Gate in Ypres for the Silence, I can feel that loss. Some early mornings on the battlefield, just as the sun comes up, there is an overwhelming sense of peace which contrasts the events we are there to remember."

I took that photograph in Delville Wood, in France. Beneath those warming rays of sunshine the remains of many "missing" British and South African solders have been buried since 1916. This idyllic scene belies the fact that parts of the wood are out of bounds, due to unexploded ordinance that also rests beneath the ground.

The truth is that the population at home had little idea about the truth of battle, or of the everyday lives of the soldiers (much time waiting for battle while waging war with lice in their clothing). They only knew that everyone had to "do their bit." I wonder about that a lot, the fact that today our armies are engaged in war overseas and we understand so little about their true experiences, the pressures, the good times, the horrendous times. And most of us have suffered no deprivation as a result of war. It's important to remember that real soldiers don't pack up and leave the set every day, so I admire Bryan's living history commemorative group, the Khaki Chums, and their mission.

You might be interested in an essay I wrote following my first visit to the battlefields of The Somme and Ypres, in 2004: http://jacquelinewinspear.com/essays-skylarks.php

I'd love to hear your comments on this post (I understand that too many advertisements are really annoying Downton Abbey fans in the UK) and next week – yes, we'll be taking about "Intelligent Economy." I think we all need a bit of that right now!

And thank you again, Bryan.

Published on October 05, 2011 03:00

September 29, 2011

Downton Abbey and the Great War, and a fearless woman from Oz ….

I am counting down the days until I go to the UK at the end of October, so I can catch a few episodes of the new Downton Abbey. I can't wait until it hits the screens here in the USA – and I don't even have a television (I am generally so disappointed with almost everything on offer, it's just not worth it. Instead I watch movies or TV series I'm interested in on a big screen linked to my laptop – it works for me!).

I know there are those – somewhere – who didn't care for Downton Abbey; people who are sticklers for the facts of life at the time, and are of the opinion that Downton Abbey was a bit of a costume drama circus. But this is television, and to tell the truth of a period well in a manner that engages people, sometimes those facts of life at the time must be subject to a little massage.

I thought the series caught the mood of those years leading up to the Great War in 1914 very well indeed – and (for those of you who know what I am talking about) – that final scene at the end of the first series, when war was announced in the midst of a summer garden party, just took my breath away. I knew it was coming.

In fact, as soon as the series started, I knew how it was going to end, who might enlist immediately, who might be lost, who would come home terribly wounded – and how everyone would be changed forever. And I think we all knew that Lady Sybil, the adventurous youngest daughter of the Earl of Grantham, would be throwing herself into the deep end as soon as she could.

The interesting thing for me was the way women were portrayed in the first series, so that viewers learned a little more about the social pressures and opportunities of the time – cultural realities that were to change as a result of war. There was the young maid who was secretly teaching herself typing and secretarial skills – only to be reprimanded for thinking she could rise above her station. I loved the way she did just that in the final episode – but how might that opportunity change with war? For the daughters of the aristocracy, there was the pressure to find a husband given the limitations of inheritance. And at the other end of the scale, we learned about industrial unrest, and about the lower classes questioning the way of the world as it was – remember the young chauffeur, another one who had socialist ideas? And there were the characters who would never want the old order to change – Maggie Smith's Dowager Countess has some more surprises coming, I would imagine. Going back to that final scene in the first series of Downton Abbey, I felt the garden party represented a microcosm of life, in a way. So many of those who have chronicled the age speak of the golden summers before war was declared – but golden for whom? Maybe we were only given just a few scenes of the truly poverty stricken because it doesn't do much for the costume envy factor.

I'll be coming back to Downton Abbey after it's been aired over here in the USA – I am looking forward to see how the period of the Great War is treated, and how those beloved characters develop throughout a time that effectively launched the 20th Century. It may have officially begun some 14 years earlier, but to all intents and purposes, the world was till in the Edwardian age during the years 1900-1914.

And before I leave you this week, I wanted to share something of a super book I'm currently reading, published in 1915: A WOMAN'S EXPERIENCES IN THE GREAT WAR, by Australian author, poet, journalist /war correspondent, Louise Mack. She reported from the front line for two British newspapers – the first woman war correspondent in the Great War. What is interesting – bringing me back to Downton Abbey and the manners of the time – is that she travels to the front lines in Belgium as if she were setting off on a little European tour, and in her memoir she admits that, "When I look back on those days, the most pathetic thing about it all seems to me the absolute security in which we imagined ourselves dwelling." Indeed, while being escorted to Antwerp by a general, she drops a bag, to reveal a pair of brilliant blue evening shoes with high heels and silver buckles. And while in Antwerp in the early days of the war, she describes being in her hotel room during a Zeppelin raid, and of course there is a complete black out:

"It seemed to me that the supreme satisfaction of having at last dropped clean away from all the make-believes of life, seized upon me, standing there in my nightgown in the pitchblack, airless room at Antwerp, a woman quite alone among strangers, with danger knocking at the gate of her world."

That's Louisa Mack.

Last week's post, about the women who went into the workplace during the Great War, resonates with the final paragraphs of Mack's memoir, when she arrives back in London after being so close to the fighting:

"And while we are laughing the train runs into Victoria Station and the soldiers leap joyously out into the rain-wet London night. Then dear familiar words break on our ears, in a woman's voice.'Any luggage, Mum!' says a woman porter.And we know that old England is carrying on as usual.'"

I'm sure I'll be coming back to Louise Mack and her insightful observations.

Perhaps readers in the UK – where the new series of Downton Abbey is already on the screen – can tell us if they feel the time is being depicted in an authentic manner. I'd be interested to know – but try not to give us any spoilers!

And how do you feel about film and TV depictions of difficult times? Do you feel that women, especially, are given a true representation? And can you detect hidden propaganda in those films? Ah, there's a subject for another post along the way….

Next Post: Intelligent Economy – from an article of that title published in 1916. Does this sound like something we need now???? Sign up for email alerts so you know when a new post appears - click on the "Subscribe by Email" option in the right-hand margin above.

Published on September 29, 2011 03:30

September 22, 2011

The Surplus Women, A Book Recommendation, and a Competition!

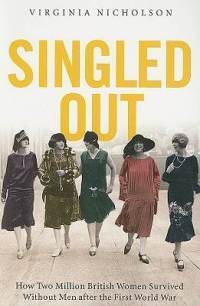

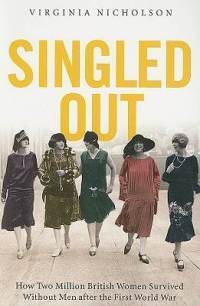

In her book, "SINGLED OUT: HOW TWO MILLION WOMEN SURVIVED WITHOUT MEN AFTER THE FIRST WORLD WAR," Virginia Nicholson recounted the following story: In 1917 the headmistress of Bournemouth High School for Girls in southern England made a breathtaking announcement to the girls in her sixth form (generally 16-17 year olds), "I have come to tell you a terrible fact. Only one out of ten of you girls can ever marry …. Nearly all the men who might have married you have been killed. You will have to make your way in the world as best you can."

Wow - I wonder how any of us would have felt with that little snippet of information rolling around in our heads? Certainly many of us who are baby boomers might not have felt too put out at first – the 1960's and 70's were a different time, after all. But these were young women who had been brought up by mothers steeped in the mores of the Victorian era, when a woman's fulfillment was expected to come through marriage, children and the home.

So, what was at the root of this prediction, and what happened to those women?

The first question is easy to answer, but hard to take. The Great War 1914-1918, as the First World War is often known, claimed the lives of some 750,000 young men of marriageable age in Britain. In addition, about 1,350,000 were seriously wounded, and another 200,000 profoundly shell-shocked (the "Official" line was 80,000 shell-shocked, but recent research reveals the number to be dramatically higher – the original numbers having been massaged to minimize the impact of war pension claims).

Now to the second question – what happened to those women?

The 1921 census revealed that there were over 2,000,000 "surplus" women of marriageable age in Britain for whom there would never be a husband or children. Indeed, a pamphlet was published: The Problem of the Surplus Women. And what an insult that was, after all, those same women had been called up during the war – an additional 1.5 million women entering the workplace in highly visible roles, not only as nurses, ambulance drivers, in military support roles and munitions, but in just about every field of endeavor so that young men could be released for the battlefield machine. After the war, there was a tendency to treat those women as pariahs who were after the jobs of men – and as if it wasn't hard enough rising to the challenge of work, of making their way in a new world, these women had lost their fathers, brothers, cousins, sweethearts and friends to war. For many their grief must have been unimaginable.

How they coped, how many floundered, and how a great number rose to the challenge of a life lived alone is a subject that has certainly fascinated me since my teens, and for years I hoped that one day someone would write a really good book on the subject – not an academic treatise (there are enough of those), but a book that crackles not only with a depth of research, but through which you really hear the voices of those women. Finally that book came along when Nicholson published SINGLED OUT. And though there are historians who have countered some of her assertions, for me Nicholson's stories of the women of that era rang true to my own experience.

When I was a child, those women who came of age in the Great War were in their 60's, some still at work and some just retired. There were quite a few in the small hamlet in which I grew up – each addressed as "Miss" this or that, and never known by their first name, though they always gave the impression that "fortitude" might have been their middle name.

One of the tragedies for so many of that generation, was that they never knew motherhood, so bringing children into their lives became important – perhaps that's why so many became teachers or governesses, and not just because those jobs occasionally came with accommodation. I remember often being invited to tea by one of the "Misses" in our community – I would be sent on my way by my mother, in my best dress and polished shoes, and would sit for tea with a woman of a certain age, who was clearly delighted in the company of her young but temporary charge. And I remember that, as I munched on my egg sandwich cut into small triangles, or my buttered toast and jam, I would look up at the mantelpiece and see the sepia photograph of a young man lost to war – perhaps a brother, a dear friend, or a sweetheart – and I knew not to ask.

Nicholson doesn't rose-tint the lives of these women, and the book contains some heartrending stories of loneliness and separation – and also highlights the disintegration of Victorian morals as many liberated women of the 20's and 30's lived their lives in a way that might have made young women in the 60's blush! But more than anything I loved the stories of those who blazed a trail – here are just a mere handful mentioned in Nicholson's book:

Miss Gertrude Tuckwell, the first woman Justice of the Peace to be sworn in, in London.Miss Margaret Beavan, Liverpool's first Lady Mayor.Miss Reynolds, head of one of the largest publicity firms in Britain.Miss Irvine, the only professional tea-taster appointed by HM GovernmentMiss Maud West, Detective (I love that one!).

The time between the wars became the golden age of detective fiction, with many of those best-selling authors being unmarried women – there's a job you can do at home with no training!

Nicholson points out that the conditions of the first half of the twentieth century enabled women to give the very best of themselves. As Cicely Hamilton wrote:

Teach me to need no aid of men,That I may aid such men as need.

In a review of SINGLED OUT, Jane Ridley of the Literary Review pointed out that, though the memorials to the men who gave their lives grows, the women who were left behind are forgotten. With that in mind, I highly recommend SINGLED OUT to anyone interested in this era, and if you're reading this blog – that's you! Which brings me to my first competition:

I'll be sending a copy of SINGLED OUT by Virginia Nicholson to the first person to send an email to jacquelinewinspear@gmail.com. Just type "Maisie Dobbs Singled Out" on the subject line, and remember to give your full name and address.

And as a consolation prize, the next five people responding to this post (via the same email address) will receive a Maisie Dobbs "Secrets" journal. Earlier this year my publisher, Harper Collins, produced a lovely Moleskin journal in conjunction with publication of A LESSON IN SECRETS. The notebook, with a letter from me inside, was sent as a gift to booksellers, however, there were a few leftovers – and now I can give them away!

See you next week – it's time to talk about Downton Abbey and The Great War – a subject I am sure we'll come back to once or twice!

Wow - I wonder how any of us would have felt with that little snippet of information rolling around in our heads? Certainly many of us who are baby boomers might not have felt too put out at first – the 1960's and 70's were a different time, after all. But these were young women who had been brought up by mothers steeped in the mores of the Victorian era, when a woman's fulfillment was expected to come through marriage, children and the home.

So, what was at the root of this prediction, and what happened to those women?

The first question is easy to answer, but hard to take. The Great War 1914-1918, as the First World War is often known, claimed the lives of some 750,000 young men of marriageable age in Britain. In addition, about 1,350,000 were seriously wounded, and another 200,000 profoundly shell-shocked (the "Official" line was 80,000 shell-shocked, but recent research reveals the number to be dramatically higher – the original numbers having been massaged to minimize the impact of war pension claims).

Now to the second question – what happened to those women?

The 1921 census revealed that there were over 2,000,000 "surplus" women of marriageable age in Britain for whom there would never be a husband or children. Indeed, a pamphlet was published: The Problem of the Surplus Women. And what an insult that was, after all, those same women had been called up during the war – an additional 1.5 million women entering the workplace in highly visible roles, not only as nurses, ambulance drivers, in military support roles and munitions, but in just about every field of endeavor so that young men could be released for the battlefield machine. After the war, there was a tendency to treat those women as pariahs who were after the jobs of men – and as if it wasn't hard enough rising to the challenge of work, of making their way in a new world, these women had lost their fathers, brothers, cousins, sweethearts and friends to war. For many their grief must have been unimaginable.

How they coped, how many floundered, and how a great number rose to the challenge of a life lived alone is a subject that has certainly fascinated me since my teens, and for years I hoped that one day someone would write a really good book on the subject – not an academic treatise (there are enough of those), but a book that crackles not only with a depth of research, but through which you really hear the voices of those women. Finally that book came along when Nicholson published SINGLED OUT. And though there are historians who have countered some of her assertions, for me Nicholson's stories of the women of that era rang true to my own experience.

When I was a child, those women who came of age in the Great War were in their 60's, some still at work and some just retired. There were quite a few in the small hamlet in which I grew up – each addressed as "Miss" this or that, and never known by their first name, though they always gave the impression that "fortitude" might have been their middle name.

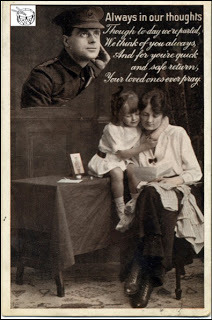

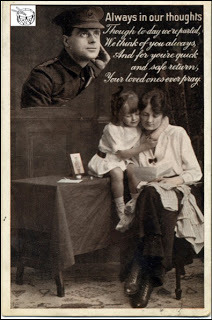

One of the tragedies for so many of that generation, was that they never knew motherhood, so bringing children into their lives became important – perhaps that's why so many became teachers or governesses, and not just because those jobs occasionally came with accommodation. I remember often being invited to tea by one of the "Misses" in our community – I would be sent on my way by my mother, in my best dress and polished shoes, and would sit for tea with a woman of a certain age, who was clearly delighted in the company of her young but temporary charge. And I remember that, as I munched on my egg sandwich cut into small triangles, or my buttered toast and jam, I would look up at the mantelpiece and see the sepia photograph of a young man lost to war – perhaps a brother, a dear friend, or a sweetheart – and I knew not to ask.

Nicholson doesn't rose-tint the lives of these women, and the book contains some heartrending stories of loneliness and separation – and also highlights the disintegration of Victorian morals as many liberated women of the 20's and 30's lived their lives in a way that might have made young women in the 60's blush! But more than anything I loved the stories of those who blazed a trail – here are just a mere handful mentioned in Nicholson's book:

Miss Gertrude Tuckwell, the first woman Justice of the Peace to be sworn in, in London.Miss Margaret Beavan, Liverpool's first Lady Mayor.Miss Reynolds, head of one of the largest publicity firms in Britain.Miss Irvine, the only professional tea-taster appointed by HM GovernmentMiss Maud West, Detective (I love that one!).

The time between the wars became the golden age of detective fiction, with many of those best-selling authors being unmarried women – there's a job you can do at home with no training!

Nicholson points out that the conditions of the first half of the twentieth century enabled women to give the very best of themselves. As Cicely Hamilton wrote:

Teach me to need no aid of men,That I may aid such men as need.

In a review of SINGLED OUT, Jane Ridley of the Literary Review pointed out that, though the memorials to the men who gave their lives grows, the women who were left behind are forgotten. With that in mind, I highly recommend SINGLED OUT to anyone interested in this era, and if you're reading this blog – that's you! Which brings me to my first competition:

I'll be sending a copy of SINGLED OUT by Virginia Nicholson to the first person to send an email to jacquelinewinspear@gmail.com. Just type "Maisie Dobbs Singled Out" on the subject line, and remember to give your full name and address.

And as a consolation prize, the next five people responding to this post (via the same email address) will receive a Maisie Dobbs "Secrets" journal. Earlier this year my publisher, Harper Collins, produced a lovely Moleskin journal in conjunction with publication of A LESSON IN SECRETS. The notebook, with a letter from me inside, was sent as a gift to booksellers, however, there were a few leftovers – and now I can give them away!

See you next week – it's time to talk about Downton Abbey and The Great War – a subject I am sure we'll come back to once or twice!

Published on September 22, 2011 03:00

September 6, 2011

Introduction to the blog

Those of you who are familiar with my historical mystery series featuring 1930's psychologist and investigator Maisie Dobbs, will know that in creating the character of Maisie Dobbs, I have drawn upon my interest and admiration for the women - of Britain, in particular - who came of age in the years of the Great War, 1914-1918, and who were, effectively, the first generation of women to go to war in modern times, and also to move into "men's work" in great numbers so that men could be released to the battlefield. For many of those women, life would never be the same again. The 1921 census revealed that there were two million "surplus" women of marriageable age in Britain, and only one in ten would have the opportunity of marriage given the great losses of marriageable young men in what became known as "the war to end all wars."

As I created the character of Maisie Dobbs, and as she revealed herself to me - and I think most authors would agree that character development seems to be a two-way process - I wanted her to reflect something of the spirit of that generation. For many years, long before I became a writer of fiction, I had collected books written for, by and about that generation, and was fascinated by the way so many navigated waters that were unfamiliar to them, and who realized that at war's end the landscape of opportunity had changed dramatically for women. There were many who understood that they would have to be responsible for their own financial security for the rest of their lives, that they would have to build community or become invisible, and they would have to nurture relationships to sustain them as they grew older. And so many of these women blazed a trail, moving into public life as never before.

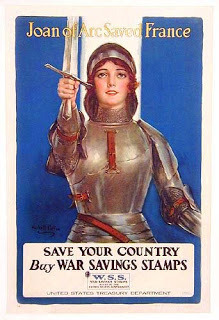

But any one book or article cannot tell the whole story, cannot explore the gray areas - for example, the fact that throughout both the first and second world wars propaganda to encourage women into the workplace could be both encouraging and demeaning, on the one hand offering independence, and on the other reminding women that they would always be playing second fiddle to the men they were replacing.

I have always found these women - who lived, worked and served in the Great War, who navigated their way through the 1920's and 30's, then served again in the Second World War - inspiring, and in the time I have been writing the Maisie Dobbs series, I have come to realize that so many readers are curious about the generations encompassed by this period in time - I've received a great number of letters and emails from women and men of all ages who have been inspired to learn more, and to journey back into their own family archives (even if "archive" amounts to a box of photographs) to discover the history of their mothers, grandmothers and great-grandmothers. I have heard from so many readers anxious to share the family stories they've uncovered. Which brings me to this blog.

In each post I'll be delving into the stories and articles about and by this generation of women that I've uncovered during my own research into the era. I would love to hear your stories too, as time goes on. My posts will not be regular - sometimes there might be a couple each week, or a week might go by with no post - so please subscribe to the blog; you'll receive an alert every time a new post is published. It might be a story about a woman of the time, perhaps one of my heroines; an interview with an author who has written a non-fiction book about the era, or a discussion about an article written in a magazine published between the wars with advice that could serve us today. I'll be sharing information on some of the books about this extraordinary generation of women that I have found particularly engaging - and if I like a book enough, I'll buy a second copy and give it away in a competition. Note that I will not be including reviews or opinions on current fiction focused on this generation - there are already many terrific blogs dedicated to new fiction and I don't want to add to that sea of personal opinion. Having said that, you'll see cover art for my own books featured on the site - frankly, I love the covers, so I splash them around whenever I can.

Some time ago I read an article in Britain's Guardian newspaper entitled, "Where are all the daring women's heroines?" Good question. My heroines have invariably come from a period in history that encompassed two world wars, the Depression, the so-called "Roaring Twenties" and the austerity Thirties. I have chosen to name my blog after Maisie Dobbs, the name given to the main character in my novels. In a way she is my everywoman of the time, a woman who is not without her faults, but who stands for a singular generation of women who have fascinated me since girlhood. In mythology, heroines fill us with awe and inspire us. I hope you find this blog interesting, inspiring and thought-provoking. I'll do my best to make it so.

Look out for the next post: Those Surplus Women, plus a book recommendation to get us started, and a competition!

As I created the character of Maisie Dobbs, and as she revealed herself to me - and I think most authors would agree that character development seems to be a two-way process - I wanted her to reflect something of the spirit of that generation. For many years, long before I became a writer of fiction, I had collected books written for, by and about that generation, and was fascinated by the way so many navigated waters that were unfamiliar to them, and who realized that at war's end the landscape of opportunity had changed dramatically for women. There were many who understood that they would have to be responsible for their own financial security for the rest of their lives, that they would have to build community or become invisible, and they would have to nurture relationships to sustain them as they grew older. And so many of these women blazed a trail, moving into public life as never before.

But any one book or article cannot tell the whole story, cannot explore the gray areas - for example, the fact that throughout both the first and second world wars propaganda to encourage women into the workplace could be both encouraging and demeaning, on the one hand offering independence, and on the other reminding women that they would always be playing second fiddle to the men they were replacing.

I have always found these women - who lived, worked and served in the Great War, who navigated their way through the 1920's and 30's, then served again in the Second World War - inspiring, and in the time I have been writing the Maisie Dobbs series, I have come to realize that so many readers are curious about the generations encompassed by this period in time - I've received a great number of letters and emails from women and men of all ages who have been inspired to learn more, and to journey back into their own family archives (even if "archive" amounts to a box of photographs) to discover the history of their mothers, grandmothers and great-grandmothers. I have heard from so many readers anxious to share the family stories they've uncovered. Which brings me to this blog.

In each post I'll be delving into the stories and articles about and by this generation of women that I've uncovered during my own research into the era. I would love to hear your stories too, as time goes on. My posts will not be regular - sometimes there might be a couple each week, or a week might go by with no post - so please subscribe to the blog; you'll receive an alert every time a new post is published. It might be a story about a woman of the time, perhaps one of my heroines; an interview with an author who has written a non-fiction book about the era, or a discussion about an article written in a magazine published between the wars with advice that could serve us today. I'll be sharing information on some of the books about this extraordinary generation of women that I have found particularly engaging - and if I like a book enough, I'll buy a second copy and give it away in a competition. Note that I will not be including reviews or opinions on current fiction focused on this generation - there are already many terrific blogs dedicated to new fiction and I don't want to add to that sea of personal opinion. Having said that, you'll see cover art for my own books featured on the site - frankly, I love the covers, so I splash them around whenever I can.

Some time ago I read an article in Britain's Guardian newspaper entitled, "Where are all the daring women's heroines?" Good question. My heroines have invariably come from a period in history that encompassed two world wars, the Depression, the so-called "Roaring Twenties" and the austerity Thirties. I have chosen to name my blog after Maisie Dobbs, the name given to the main character in my novels. In a way she is my everywoman of the time, a woman who is not without her faults, but who stands for a singular generation of women who have fascinated me since girlhood. In mythology, heroines fill us with awe and inspire us. I hope you find this blog interesting, inspiring and thought-provoking. I'll do my best to make it so.

Look out for the next post: Those Surplus Women, plus a book recommendation to get us started, and a competition!

Published on September 06, 2011 17:02