Kenneth D. Ackerman's Blog, page 3

November 21, 2012

Health food claims? Nothing new here.

From the New York City's Jewish Daily News, July 12, 1926.

From the New York City's Jewish Daily News, July 12, 1926.

"Zeit Gezunt!" says the headline. "Be Healthy!"

This quarter-page ad for the "Natural Health Food Store" comes from the July 1926 Jewish Daily News , a favorite among Yiddish-speaking Jewish immigrants on New York's crowded lower East Side back then, almost 90 years ago. But the ad could have come from any health food store, then or now. People have always wanted to eat well, eat healthy, eat smart. But back then, long before claims were checked by any government agency like the US Food and Drug Administration, the chance of being fooled by smooth-talking nonsense was much greater.

"Eat Natually Healthy Food!" this ad says -- using phonetic Hebrew letters to spell out English words like "naturally" or "specialty" or "rhumitism," words with no Yiddish equivalent that immigrants barely understood. Still, they sounded wonderful, just like the handsome, bare-chested young man in the drawing and the gorgeous-looking plate of grapes, bananas, pears and apples in his hand.

For just $3, the Natural Health Food Store offered you a wonderful meal that, among other things, would cure diabetes, stomach flu, kidney disease, and over-eating. How did you know? Because they said so. And perhaps hopefully because nobody who ate there got sick before walking out.

People today may complain that government regulators sometimes are too strict or intrusive in demanding honest disclosures about what we eat. Sometimes too much information causes confusion or can be misleading, or there are honest diisagreements about the underlying science. But don't forget the big picture. Given the choice, I'd still rather have an FDA and all the other government watchdogs, with all their faults, then none at all.

But that's just me. (And a well-earned thanks to my colleague Dick Siegel of OFWLAW for his help in deciphering the Yiddish.)

From the New York City's Jewish Daily News, July 12, 1926.

From the New York City's Jewish Daily News, July 12, 1926."Zeit Gezunt!" says the headline. "Be Healthy!"

This quarter-page ad for the "Natural Health Food Store" comes from the July 1926 Jewish Daily News , a favorite among Yiddish-speaking Jewish immigrants on New York's crowded lower East Side back then, almost 90 years ago. But the ad could have come from any health food store, then or now. People have always wanted to eat well, eat healthy, eat smart. But back then, long before claims were checked by any government agency like the US Food and Drug Administration, the chance of being fooled by smooth-talking nonsense was much greater.

"Eat Natually Healthy Food!" this ad says -- using phonetic Hebrew letters to spell out English words like "naturally" or "specialty" or "rhumitism," words with no Yiddish equivalent that immigrants barely understood. Still, they sounded wonderful, just like the handsome, bare-chested young man in the drawing and the gorgeous-looking plate of grapes, bananas, pears and apples in his hand.

For just $3, the Natural Health Food Store offered you a wonderful meal that, among other things, would cure diabetes, stomach flu, kidney disease, and over-eating. How did you know? Because they said so. And perhaps hopefully because nobody who ate there got sick before walking out.

People today may complain that government regulators sometimes are too strict or intrusive in demanding honest disclosures about what we eat. Sometimes too much information causes confusion or can be misleading, or there are honest diisagreements about the underlying science. But don't forget the big picture. Given the choice, I'd still rather have an FDA and all the other government watchdogs, with all their faults, then none at all.

But that's just me. (And a well-earned thanks to my colleague Dick Siegel of OFWLAW for his help in deciphering the Yiddish.)

Published on November 21, 2012 14:12

September 25, 2012

FAMILY HISTORY: Anniversary- One hundred years in America.

Copy of the original ship's manifest. Our family is listed at lines ten through fourteen. From Ancestry.com.I can't let this September go without marking an anniversary for my own family. It was exactly one hundred years ago this month that my father, Bill Ackerman, landed in America. My mother would come a few years later, in 1926, and they would meet on the lower East Side of NYC. The rest, as they say, is history.

Copy of the original ship's manifest. Our family is listed at lines ten through fourteen. From Ancestry.com.I can't let this September go without marking an anniversary for my own family. It was exactly one hundred years ago this month that my father, Bill Ackerman, landed in America. My mother would come a few years later, in 1926, and they would meet on the lower East Side of NYC. The rest, as they say, is history.

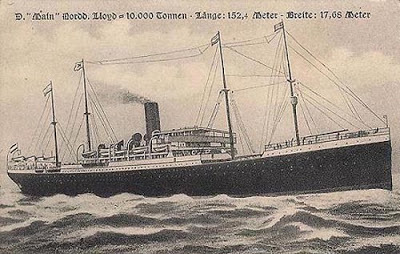

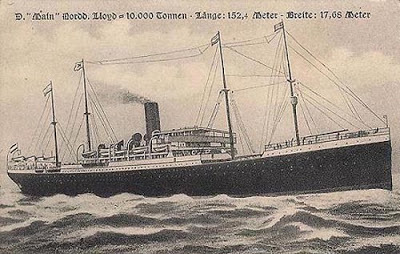

My Dad was five years old at the time. (In the photo below, taken in Poland, he is the baby sitting on his mother's lap. On the ship's manifest above, he is listed on line 14 under his Yiddish name, Meier Zev.) Their ship, the SS Main , left Bremen and landed in New York on September 19, 1912. On their reasons for the trip, see A Love Story from Poland - Sheah and Yetta Akierman.

Photo taken shortly before leaving Poland, circa 1910. The children Ruchel, Bill (Meier Zev), and Chafa and Feiga are left to right, with Yetta (Yachel) seated in the middle and Abe, the oldest son, standing behind.

Photo taken shortly before leaving Poland, circa 1910. The children Ruchel, Bill (Meier Zev), and Chafa and Feiga are left to right, with Yetta (Yachel) seated in the middle and Abe, the oldest son, standing behind.

Here's how my Aunt Rachel (the little girl Ruchel standing on my Dad's right in the photo above) described the trip many years later in her self-published memoir Horseradish: Jewish Roots . Enjoy-

"In 1912 we were ready to leave for America. From our little town we took a horse and cart to Yanow. From there we took a train to Warsaw.

"In Warsaw I met my father's mother, who I had never seen before. We stayed overnight with them. My grandmother was straight, tall and very quiet. She kissed us and cried because she was an old woman and knew she would never see us again. Aunt Geitle Vlotover gave us presents from her store to take along with us on the train to Hamburg. In the morning we took the train to Hamburg, Germany, to reach the ship, the Main, that was leaving for America.

.....

"We sailed on the Main for thirteen days. We traveled 3rd class. It was very crowded and we had to stand in line with tin plates like animals to get food. Most of the people got seasick and stood by the rails all day vomiting or rolling on the decks, too ill to get up.

"My mother and Hannah were very, very sick. Fanny, Bill and I were the only ones who were okay. Bill was too young to remember anything.

"While I was on the ship, I missed my friends and thought about the little town that I had left. I remembered how we used to do the wash by a little brook. You had to lift your skirts not to get wet, then kneel by the rocks and wash the clothes with soap and then bang them with the rocks.

.....

The Main, the ship that brought my family to America in 1912. "After a few days on the ocean, many people began to get very, very sick – in addition to the sea sickness. Some of them died and were buried at sea. The waves looked so high to me that they seemed to reach the sky. We were very frightened. My mother and sister Hannah got very sick also. We cried because we were afraid they would die and be thrown overboard like the other dead people we saw. Hannah was delirious and had a high fever. So did my mother.

The Main, the ship that brought my family to America in 1912. "After a few days on the ocean, many people began to get very, very sick – in addition to the sea sickness. Some of them died and were buried at sea. The waves looked so high to me that they seemed to reach the sky. We were very frightened. My mother and sister Hannah got very sick also. We cried because we were afraid they would die and be thrown overboard like the other dead people we saw. Hannah was delirious and had a high fever. So did my mother.

"On the 12th day out we were on the deck crying and the sailors were talking to us. They told us that, in a couple of hours, we would be in sight of land. They knew this because they could see birds flying.

"While we were standing there a miracle occurred. We saw our mother and Hannah coming to us on the deck from the sick bay. We started to scream and shout in disbelief.

"My mother told us later she had a dream while she had the fever, and Hannah had the same dream at the exact time. They dreamt that my mother’s dead brother, Moses Zies, had come to them. He gave them a piece of veal to eat and even told them to suck on the bones. They dreamt that they did what he told them to do, although in reality they had been throwing up since coming aboard the ship. The dream meat tasted delicious, they said. As they told the story, they vomited one more time, but from that moment on they were well.

"One of the funnier things that happened to us on the ship took place earlier in the voyage. The sailors pointed out to my mother that we were passing London. My mother's half-brother, Jack Baumiel, lived in London. Although there was no land in sight, my mother made us line up at the rail and wave "hello" to Uncle Yankle.

"I remember the food they gave us was so salty you could hardly eat it. We used to take a walk to the upper decks to see how the 1st and 2nd class passengers lived. There were tables and fancy dining rooms, and we were jealous.

"We landed on a beautiful day in September. We passed the Statue of Liberty and landed at a place called Castle Gardens [the US government immigration station on the lower tip of Manhattan]. We were among the first ones off the ship.

.....

"We got off the ship and all the immigrants were herded into a big building on the water's edge. The first thing that happened was an eye examination by doctors. Anyone who had a disease was sent right back to Europe.

"As we stood in the line waiting, my mother prayed that they wouldn't find anything wrong with us. We all passed. After that, we waited less than ten minutes before my father, my aunt Nettie, my sister Helen, and Nettie’s husband the policeman, all appeared to greet us. By now, Helen had gotten married and had a little six month-old girl named Florence.

"They took us to my aunt Nettie's store where she had rooms in the back. The address was 24 Second Avenue in Manhattan. We couldn't believe we were on American soil. Everyone talked English at us and we couldn't make out what they said. I thought they were talking about us. ....."

Copy of the original ship's manifest. Our family is listed at lines ten through fourteen. From Ancestry.com.I can't let this September go without marking an anniversary for my own family. It was exactly one hundred years ago this month that my father, Bill Ackerman, landed in America. My mother would come a few years later, in 1926, and they would meet on the lower East Side of NYC. The rest, as they say, is history.

Copy of the original ship's manifest. Our family is listed at lines ten through fourteen. From Ancestry.com.I can't let this September go without marking an anniversary for my own family. It was exactly one hundred years ago this month that my father, Bill Ackerman, landed in America. My mother would come a few years later, in 1926, and they would meet on the lower East Side of NYC. The rest, as they say, is history.My Dad was five years old at the time. (In the photo below, taken in Poland, he is the baby sitting on his mother's lap. On the ship's manifest above, he is listed on line 14 under his Yiddish name, Meier Zev.) Their ship, the SS Main , left Bremen and landed in New York on September 19, 1912. On their reasons for the trip, see A Love Story from Poland - Sheah and Yetta Akierman.

Photo taken shortly before leaving Poland, circa 1910. The children Ruchel, Bill (Meier Zev), and Chafa and Feiga are left to right, with Yetta (Yachel) seated in the middle and Abe, the oldest son, standing behind.

Photo taken shortly before leaving Poland, circa 1910. The children Ruchel, Bill (Meier Zev), and Chafa and Feiga are left to right, with Yetta (Yachel) seated in the middle and Abe, the oldest son, standing behind. Here's how my Aunt Rachel (the little girl Ruchel standing on my Dad's right in the photo above) described the trip many years later in her self-published memoir Horseradish: Jewish Roots . Enjoy-

"In 1912 we were ready to leave for America. From our little town we took a horse and cart to Yanow. From there we took a train to Warsaw.

"In Warsaw I met my father's mother, who I had never seen before. We stayed overnight with them. My grandmother was straight, tall and very quiet. She kissed us and cried because she was an old woman and knew she would never see us again. Aunt Geitle Vlotover gave us presents from her store to take along with us on the train to Hamburg. In the morning we took the train to Hamburg, Germany, to reach the ship, the Main, that was leaving for America.

.....

"We sailed on the Main for thirteen days. We traveled 3rd class. It was very crowded and we had to stand in line with tin plates like animals to get food. Most of the people got seasick and stood by the rails all day vomiting or rolling on the decks, too ill to get up.

"My mother and Hannah were very, very sick. Fanny, Bill and I were the only ones who were okay. Bill was too young to remember anything.

"While I was on the ship, I missed my friends and thought about the little town that I had left. I remembered how we used to do the wash by a little brook. You had to lift your skirts not to get wet, then kneel by the rocks and wash the clothes with soap and then bang them with the rocks.

.....

The Main, the ship that brought my family to America in 1912. "After a few days on the ocean, many people began to get very, very sick – in addition to the sea sickness. Some of them died and were buried at sea. The waves looked so high to me that they seemed to reach the sky. We were very frightened. My mother and sister Hannah got very sick also. We cried because we were afraid they would die and be thrown overboard like the other dead people we saw. Hannah was delirious and had a high fever. So did my mother.

The Main, the ship that brought my family to America in 1912. "After a few days on the ocean, many people began to get very, very sick – in addition to the sea sickness. Some of them died and were buried at sea. The waves looked so high to me that they seemed to reach the sky. We were very frightened. My mother and sister Hannah got very sick also. We cried because we were afraid they would die and be thrown overboard like the other dead people we saw. Hannah was delirious and had a high fever. So did my mother."On the 12th day out we were on the deck crying and the sailors were talking to us. They told us that, in a couple of hours, we would be in sight of land. They knew this because they could see birds flying.

"While we were standing there a miracle occurred. We saw our mother and Hannah coming to us on the deck from the sick bay. We started to scream and shout in disbelief.

"My mother told us later she had a dream while she had the fever, and Hannah had the same dream at the exact time. They dreamt that my mother’s dead brother, Moses Zies, had come to them. He gave them a piece of veal to eat and even told them to suck on the bones. They dreamt that they did what he told them to do, although in reality they had been throwing up since coming aboard the ship. The dream meat tasted delicious, they said. As they told the story, they vomited one more time, but from that moment on they were well.

"One of the funnier things that happened to us on the ship took place earlier in the voyage. The sailors pointed out to my mother that we were passing London. My mother's half-brother, Jack Baumiel, lived in London. Although there was no land in sight, my mother made us line up at the rail and wave "hello" to Uncle Yankle.

"I remember the food they gave us was so salty you could hardly eat it. We used to take a walk to the upper decks to see how the 1st and 2nd class passengers lived. There were tables and fancy dining rooms, and we were jealous.

"We landed on a beautiful day in September. We passed the Statue of Liberty and landed at a place called Castle Gardens [the US government immigration station on the lower tip of Manhattan]. We were among the first ones off the ship.

.....

"We got off the ship and all the immigrants were herded into a big building on the water's edge. The first thing that happened was an eye examination by doctors. Anyone who had a disease was sent right back to Europe.

"As we stood in the line waiting, my mother prayed that they wouldn't find anything wrong with us. We all passed. After that, we waited less than ten minutes before my father, my aunt Nettie, my sister Helen, and Nettie’s husband the policeman, all appeared to greet us. By now, Helen had gotten married and had a little six month-old girl named Florence.

"They took us to my aunt Nettie's store where she had rooms in the back. The address was 24 Second Avenue in Manhattan. We couldn't believe we were on American soil. Everyone talked English at us and we couldn't make out what they said. I thought they were talking about us. ....."

Published on September 25, 2012 09:54

September 13, 2012

GUEST BLOG: Civil War- Antietam 1862 and its terrible general, George B. McClellan

Oil painting of General George Brinton McClellan, from a photograph by Matthew Brady.

Oil painting of General George Brinton McClellan, from a photograph by Matthew Brady. With all attention these days on the national political campaign, let's not forget another big item this month, the 150th anniversary of Antietam, the bloodiest single-day battle in American history. With 23,000 casualties, Antietam marked a turning point in the Civil War, prompting President Abraham Lincoln to move ahead with his Emancipation Proclamation while also ending the military career of the Union's controversial general, George Brinton McClellan. McClellan's refusal to chase the enemy, either before or after the battle, finally would led Lincoln to take away his command.

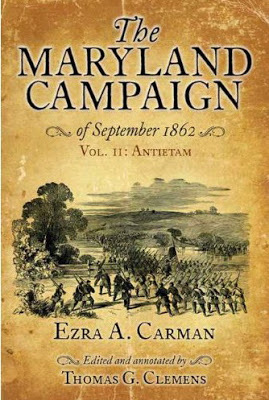

In the new book The Maryland Campaign of 1862:Vol.. II: Antietam, Thomas Clemens brings us a newly edited and annotated version of the original intimate account from Ezra Carman, a Union officer who commanded the 13th New Jersey Volunteers at Antietam and became the country's leading scholar on the battle. In this excerpt, he focuses on McClellan's hesitancy the day before the big shootout. (Click here to see the book trailer on YouTube):

During the afternoon and night of the 15th McClellan’s forces moved to the positions assigned them, but it was not until after daybreak of the 16th that the great body of them were in their designated places, some brigades did not get up until noon. Hooker’s (First) Corps was in the forks of the Big and Little Antietam. Sumner’s (Second) Corps was on both sides of the Boonsboro and Sharpsburg road, Richardson’s Division in advance, near the Antietam, on the right of the road. Sykes’ Division was on the left of Richardson’s, and on Sykes’ left and rear was Burnside’s (Ninth) Corps. Mansfield’s (Twelfth) Corps was at Nicodemus Mill or Springvale. Pleasonton’s cavalry division was just west of Keedysville.7

Near midnight of the 15th two companies each of the 61st and 64th New York, under command of Lieutenant Colonel Nelson A. Miles, passed along the rear of Sedgwick’s Division and some distance along the bluff below the “middle bridge”, then turning back reached the bridge just as a party of Union cavalry came riding sharply over it from the south bank. They informed Miles that the enemy had fallen back and that there were none in the immediate front of the bridge. Miles crossed the bridge to the west side of the creek, and marched cautiously west along the highway.

Near midnight of the 15th two companies each of the 61st and 64th New York, under command of Lieutenant Colonel Nelson A. Miles, passed along the rear of Sedgwick’s Division and some distance along the bluff below the “middle bridge”, then turning back reached the bridge just as a party of Union cavalry came riding sharply over it from the south bank. They informed Miles that the enemy had fallen back and that there were none in the immediate front of the bridge. Miles crossed the bridge to the west side of the creek, and marched cautiously west along the highway. It was then daybreak. A heavy fog prevented vision for more than fifteen or twenty feet; the dust in the road deadened the sound of the footsteps and silence was enjoined. Miles who was in advance, had reached the crest of the ridge about 600 yards beyond the Antietam, and was about to descend into the broad ravine where the Confederates were in position, when he ran upon a Confederate crossing the road, whom he captured and from whom he learned, that he was very near the Confederate line. The command was faced about and moved back with as much silence and celerity as possible, and recrossed the bridge before the fog lifted, but long after daylight of the 16th.

There has been much criticism on the failure of McClellan to attack Lee on the afternoon of the 15th or at least early on the 16th. We have referred to the failure to do so on the 15th. The situation, inviting prompt attack on the morning of the 16th, is well stated by General F. A. Walker in the History of the Second Army Corps:

"If it be admitted to have been impracticable to throw the 35 brigades that had crossed the South Mountain at Turner’s Gap across the Antietam during the 15th, in season and in condition to undertake attack upon Lee’s 14 brigades that day with success, it is difficult to see what excuse can be offered for the failure to fight the impending battle on the 16th, and that early. It is true that Lee’s forces had then been increased by the arrival of Jackson with J. R. Jones and Lawton’s divisions [also Walker’s—inserted by Carman], but those of Anderson, McLaws and A. P. Hill could not be brought up that day. A preemptory recall of Franklin, in the early evening of the 15th, would have placed his three divisions in any part of the line that might be desired. Even without Franklin, the advantages of concentration would have been on the side of McClellan. When both armies were assembled the Union forces were at least nine to six, of the Confederate six only four could possibly have been present on the 16th. Without Franklin the odds would still have been seven to four."

It is evident that McClellan had no idea of fighting Lee on the 15th. There seems to have been no intention to do it early on the 16th, certainly no orders to that effect were issued, nor did he make any preparations. In fact he expected Lee to retreat during the night of the 15th.

At 9 o’clock on the morning of the 16th, after telegraphing his wife that he had no doubt “delivered Pennsylvania and Maryland,” McClellan dispatched Halleck:

"The enemy yesterday held a position just in front of Sharpsburg. This morning a heavy fog has thus far prevented us doing more than to ascertain that some of the enemy are still there. Do not know in what force. Will attack as soon as situation of enemy is developed."

Halleck replied to this dispatch:

"I think however, you will find that the whole force of the enemy in your front has crossed the river. I fear now more than ever that they will recross at Harper’s Ferry or below and turn your left, thus cutting you off from Washington. This has appeared to me to be a part of their plan, and hence my anxiety on the subject."

When this dispatch was read by McClellan, during the afternoon of the 16th, contempt was written on his face as he remarked, “the idea of Halleck giving me lessons in the art of war.”

When the fog lifted he missed S. D. Lee’s guns, which had been moved to theleft, or, as he reports:

"It was discovered that the enemy had changed the position of his batteries. The masses of his troops, however, were still concealed behind the opposite heights. Their left and center were upon and in front of the Sharpsburg and Hagerstown Turnpike, hidden by woods and irregularities of the ground, their extreme left resting upon a wooded eminence near the cross-roads to the north of Miller’s farm, their left resting upon the Potomac (sic in McClellan’s report.) Their line extended south, the right resting upon the hills to the south of Sharpsburg near Snavely’s farm.” This changed position of the batteries is given by McClellan as one of the reasons for not making the attack before afternoon, for, he says, he was “compelled to spend the morning in reconnoitering the new position taken up by the enemy, examining the ground, finding fords, clearing the approaches, and hurrying up the ammunition and supply trains, which had been delayed by the rapid march of the troops over the few practicable approaches from Frederick. These had been crowded by the masses of infantry, cavalry and artillery pressing on with the hope of overtaking the enemy before he could form to resist an attack. Many of the troops were out of rations on the previous day, and a good deal of their ammunition had been expended in the severe action of the 14th."

From the time of McClellan’s arrival on the field until Hooker’s advance in the afternoon of the 16th, nothing seems to have been done with a view to an accurate determination of the Confederate position. From the heights east of the Antietam the eye could trace the right and center, but the extreme left could not be definitely located, nor was the character of the country on that flank known. It was upon this flank that McClellan decided to make his attack and one would suppose that his first efforts would be directed to ascertain how that flank could be approached and what it looked like. This was proper work for cavalry, of which he had a good body available for the purpose. Pleasonton’s cavalry division was in good shape and elated with its successful achievements, culminating in the discomfiture of Fitz-Hugh Lee’s Brigade at Boonsboro, the day before, and confident of its capacity for further good work. But it was not used.

As far as we know, not a Union cavalryman crossed the Antietam until Hooker went over in the afternoon of the 16th, when the 3rd Pennsylvania cavalry accompanied him. Nor can we discover that the cavalry did any productive work elsewhere. It did not ascertain that there were good fords below the Burnside Bridge, leading directly to the right-rear of the Confederate line, and we know of no order given for its use, save a suggestion to Franklin, to have his cavalry feel towards Frederick. The part taken by the cavalry this day is very briefly told by Pleasonton, in his report: “On the 16th my cavalry was engaged in reconnaissances, escorts and support to batteries.” If any part of his command, except the 3rdPennsylvania, was engaged in reconnaissances and supporting batteries we do not know of it.

The first movement of the day was to crown the bluff east of the Antietam with artillery and cover the Middle Bridge. This bluff, which, south of the bridge, almost over-hangs the Antietam, recedes from it north of the bridge for a short distance, then approaches it. It rises 180 feet above the stream and commands nearly the entire battlefield.

The Reserve Artillery, which arrived late in the evening of the 15th, was put in position, early in the morning, by General Henry J. Hunt, chief of artillery. Taft’s New York battery, and the German (New York) batteries of von Kleiser, Langner, and Wever were placed on the bluff north of the Boonsboro road, Taft’s Battery relieving Tidball’s which rejoined the cavalry division. Von Kleiser relieved Pettit’s New York battery. The four New York batteries had 20 pound Parrott guns and were supported by Richardson’s Division. South of the Boonsboro road, and about 9 a. m. Weed’s Battery (I, 5th U.S.) and Benjamin’s Battery (E, 2nd U.S.) were run up the bluff in front of Sykes’ Division. Each battery, as it came into position, opened upon such bodies of Confederate infantry as could be seen, and upon the Washington Artillery and Hood’s Division batteries, on Cemetery Hill, and the batteries on the ridge running north from it, and the reply was prompt and spirited, during which Major Albert Arndt, commanding the German artillery battalion, was mortally wounded.

As the Confederates were short of ammunition and the range too short for their guns, Longstreet ordered them to withdraw under cover of the hill. General D. H. Hill says that the Confederate artillery was badly handled and “could not cope with the superior weight, calibre, range, and number of the Yankee guns. An artillery duel between the Washington Artillery and the Yankee batteries across the Antietam, on the 16th, was the most melancholy farce in the war.” .....

Check out at Amazon.com or from the publisher at SavasBeatie.com

Published on September 13, 2012 05:48