George Packer's Blog, page 244

October 3, 2013

A Reprieve For America's Abandoned Friends?

A footnote: on Wednesday night—by unanimous consent!—the House passed a resolution that will extend the Special Immigrant Visa program for Iraqis through December. The program had officially expired at midnight on September 30th, but it was reprieved thanks to bipartisan work in both chambers, especially by Senators John McCain, Jeanne Shaheen, Patrick Leahy, and Lindsey Graham, and by representatives Earl Blumenauer, Democrat of Oregon, and Adam Kinzinger, Republican of Illinois, who is an Iraq and Afghanistan veteran.

Behind the scenes, the resolution was assiduously advocated by the Iraqi Refugee Assistance Project and, most crucially, by numerous military vets, making it the one thing in paralyzed Washington that Democrats and Republicans could agree on. The Senate had already passed the extension, which now goes to the White House for President Obama’s signature. This means that the door to immigration hasn’t completely shut on Iraqis who worked with Americans and as a result have no future in their own country. (I wrote about the shameful abandonment of interpreters and others last week.)

September 25, 2013

How Did A Friend of America Lose His Visa?

Yesterday, I wrote about Janis Shinwari, an Afghan who served as an interpreter for the U.S. Army for seven years, bravely and honorably, saving the lives of several American soldiers, including Lieutenant (now Captain) Matt Zeller. I heard about Shinwari and Zeller through Becca Heller of the Iraqi Refugee Assistance Project. There are thousands of cases of Iraqis and Afghans who risked their lives for the U.S., only to have their chance at an American visa endlessly delayed or denied. Shinwari’s story struck me as particularly unjust, because of his extraordinary record of service, and because he had actually received his visa a few weeks ago, only to have it revoked on Saturday, just after he had quit his job, sold all his possessions, and was preparing his family to start a new life in Virginia.

May 25, 2013

A Reply From Silicon Valley

The same week as my piece in The New Yorker on the political culture of Silicon Valley came two big stories from the tech world: Tumblr, a blogging platform founded by a high-school dropout (now all of twenty-six) named David Karp, was bought by Yahoo for $1.1 billion; and a Senate report revealed that Apple has pushed tax avoidance to its most creative outer limits, incorporating three ghost subsidiaries in Dublin to hide billions of dollars—almost a third of Apple’s profits over the past three years—from the United States Treasury.

Together, these stories tell us that Silicon Valley continues to create hugely popular products that generate fantastic wealth at the top; and that there is no such thing as tech exceptionalism. The technology industry remains another special interest, as intent as the oil and pharmaceutical sectors on maximizing profits and minimizing its obligation to pay taxes. Why is this surprising? Because, as I wrote in the piece, millions of people seem to take technological innovation for a social and political revolution (“Think Different”), a confusion encouraged by many tech leaders. Even Senator John McCain, after chiding Apple’s C.E.O. Tim Cook for doing his best to cheat America out of its share of the company’s patents and intellectual property, gushed to Cook, “You managed to change the world”—thereby echoing a common Silicon Valley mantra, as well as the title of my piece. (By the way, other Senate Republicans, such as Rand Paul, actually praised Apple for starving the public sector of revenue—more evidence of the institutional collapse that’s at the heart of my new book “The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America.”)

...read moreFebruary 17, 2012

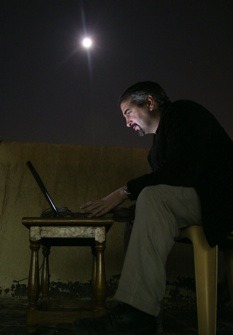

Anthony Shadid’s Passion

It’s hard to accept that there won’t be any more Anthony Shadid bylines in my morning paper. He’d been doing it so well for so long that I’d begun to take for granted his readiness to get the story of the Arab world, however hard the place—Iraq, Lebanon, Egypt, Libya, Syria—and bring it to us with his characteristic thoughtfulness and grace. What’s happening in the Iraqi south now that the Sadr militia has joined the political process? Anthony knows that terrain better than any foreigner. Is Tripoli about to fall? Shadid will get inside as soon as he can. Is Cairo having another revolution? He’s there and knows how to explain why it’s happening. If anyone can get into Homs, it’ll be Anthony. He combined professional excellence with quiet indefatigability, so that you only noticed it when he wasn’t on the scene. He was the Cal Ripken of foreign correspondents.

By the time I got to Iraq in the summer of 2003, Shadid knew so much about the state of Iraqis under American occupation that it was impossible to imagine anyone in the tribe of foreign reporters ever quite catching up. I met him in early 2004 at a poker game in the Washington Post bureau (it consisted of a few disorderly rooms at the decrepit and frequently targeted Sheraton Hotel). He was a little too gentle and transparent to be as good a poker player as he was a reporter. He wore the depth of his knowledge so lightly, and was so open with any newcomer who wanted to tap into it. I remember Anthony complaining about being taken for a spy by Sadrists in Najaf, a hazard of speaking fluent Arabic and passing in a crowd. It was a liability few other foreigners could hope to have. He kept returning to the subject of the Mahdi Army: he expressed a lot of empathy for the poor young Shiites who were flocking to its banner, even as he worried about their capacity for violence and extremism. (Not long after that night, the Sadrists staged an insurrection across the country that radically changed the course of the war.) Most of all, he knew that Iraq’s future belonged to those young Iraqis, not to the nominally pro-Western politicians with whom less deeply immersed journalists spent their time.

...read moreAnthony Shadid's Passion

It's hard to accept that there won't be any more Anthony Shadid bylines in my morning paper. He'd been doing it so well for so long that I'd begun to take for granted his readiness to get the story of the Arab world, however hard the place—Iraq, Lebanon, Egypt, Libya, Syria—and bring it to us with his characteristic thoughtfulness and grace. What's happening in the Iraqi south now that the Sadr militia has joined the political process? Anthony knows that terrain better than any foreigner. Is Tripoli about to fall? Shadid will get inside as soon as he can. Is Cairo having another revolution? He's there and knows how to explain why it's happening. If anyone can get into Homs, it'll be Anthony. He combined professional excellence with quiet indefatigability, so that you only noticed it when he wasn't on the scene. He was the Cal Ripken of foreign correspondents.

By the time I got to Iraq in the summer of 2003, Shadid knew so much about the state of Iraqis under American occupation that it was impossible to imagine anyone in the tribe of foreign reporters ever quite catching up. I met him in early 2004 at a poker game in the Washington Post bureau (it consisted of a few disorderly rooms at the decrepit and frequently targeted Sheraton Hotel). He was a little too gentle and transparent to be as good a poker player as he was a reporter. He wore the depth of his knowledge so lightly, and was so open with any newcomer who wanted to tap into it. I remember Anthony complaining about being taken for a spy by Sadrists in Najaf, a hazard of speaking fluent Arabic and passing in a crowd. It was a liability few other foreigners could hope to have. He kept returning to the subject of the Mahdi Army: he expressed a lot of empathy for the poor young Shiites who were flocking to its banner, even as he worried about their capacity for violence and extremism. (Not long after that night, the Sadrists staged an insurrection across the country that radically changed the course of the war.) Most of all, he knew that Iraq's future belonged to those young Iraqis, not to the nominally pro-Western politicians with whom less deeply immersed journalists spent their time.

His book "Night Draws Near," about the Iraqis he got to know so well those first two years of the occupation, didn't get as much attention as it deserved. Americans, predictably, were more interested in books that focussed on themselves, their own ambitions and sacrifices and wrongdoings. Now that Anthony is gone, I hope more readers will discover his book's lyricism, its humaneness, and will see how much of the tragedy of the Iraq War was contained and foreseen in the astounding work that Shadid did in those early years, when he roamed the country on his own.

The foreign reporters covering that unpredictably brutal war sometimes expressed surprise and relief at how few of us were even hurt, let alone killed. (By contrast, Iraqi journalists and fixers were getting killed almost every week.) After enough escapes and near misses, you start to think that it won't happen to you, or to anyone you really care about. But ever since the battle and the story have moved from Iraq to other countries, the odds have caught up and the world has lost—in addition to Libyan, Syrian, Egyptian, Bahraini, Afghan, and other local journalists—the filmmaker Tim Hetherington, the photographer Chris Hondros, and now the reporter Anthony Shadid, while the photographer Joao Silva was terribly wounded by a mine. To me, the fact that Tyler Hicks, who was with Anthony when he died and has been through everything that war has to offer in the decade since September 11th, is still alive constitutes a small miracle.

The usual thing to say is that they are risking, sometimes giving, their lives in order to bear witness to human facts that the rest of us need to know. This is also the correct thing to say. Anthony and the others deserve honor and gratitude as much as any fallen soldiers. Still, I wish it weren't so. I wish they didn't have to do it. I wish their kids, if they had them (Anthony had two), got to grow up with fathers. And I hope some of my friends will slow down, maybe even stop and turn to less dangerous subjects, before the wars claim them, too.

Read remembrances of Anthony Shadid by Steve Coll, Jon Lee Anderson, and Dexter Filkins.

Photograph by Bill O'Leary/AP Photo/The Washington Post.

September 9, 2011

Obama Against the Nihilists

It was a clever speech, a reminder of two things that had gone understandably forgotten through President Obama's awful summer: he's capable of passionate feeling, and he can also be politically dextrous. The feeling was indignation on behalf of the country's unemployed, underemployed, foreclosed, stretched to the limit. Not sympathy or feeling their pain—Obama doesn't do that well and didn't try last night, because it's really beside the point. As Mark Schmitt points out in the New Republic, polls show that "people no longer care that he cares. They're fed up with gestures, empathy, or good ideas that get blocked in the political process—all they want is results." No, what the President expressed was a fairly unquiet anger at Washington's—meaning Congress'—failure to act on those Americans' behalf.

That was also the politically dextrous move. Having spent the summer futilely negotiating on the Republicans' terms, he's now calling them out to negotiate on his, trying to turn disastrous economic circumstances to his advantage by presenting the choice before the country in a simple way: do something or do nothing. He didn't waste much time arguing against the Republican idea of solving all problems by cutting taxes and regulations. He just cited it and moved on, hoping that the public will see that it's beside the point, an ideology without relevance to the facts, as the country descends into another recession. The rhetoric of the speech was all pragmatic: these are the facts—do something about them, or do nothing.

My guess is that the House will give him just enough of his plan—further cuts to payroll taxes paid by employers and employees—to be able to say, We're not rank partisans and blind ideologues: we are doing something. But this wouldn't be nearly enough to reverse the downward economic slide, allowing the opposition to go on playing the game it's played since Obama's inauguration—to lay the blame on him for the results of their own acts of legislative sabotage. Power without responsibility requires a high degree of self-restraint, something lacking in the contemporary Republican Party.

Then Obama's best hope will lie with the public. Do Americans still have enough faith in him, and in government, to give the President a second shot at reviving the economy? I'm not at all sure. When he called on citizens to make their voices heard in Congress, my heart sank. Those who have tried over the past couple of years have been drowned out. In a climate of political rage and economic despair, nihilism plays a lot better. For a devastating account of how this has come to be, read this essay by a Republican House staff member who just retired in disgust after three decades.

In the past, Obama has always tried to reason with nihilism, to say, "You can't really think that. Let's find a way to compromise." That's his deepest instinct, and some version of it will resurface before long. He hates to draw bright lines and emphasize stark contrasts. But for now, he's decided to take nihilism on directly ("Pass it right away"), hoping that the public will see the difference and choose sides.

July 29, 2011

Iraqi Refugees: A Debt Defaulted

Two weeks ago, Tim Arango of the Times wrote an expose of the Administration's failure to admit into the U.S. more than a tiny number of Iraqis who were affiliated with the U.S. in Iraq. He got the government's attention. Three days later, Senator Chuck Schumer wrote a letter to Secretaries Hillary Clinton and Janet Napolitano asking why so few Iraqis who helped America are making it here. Seven other senators wrote to Napolitano separately. "If these individuals do not deserve a visa," Schumer wrote, "it is hard to imagine who does." The Senator even went so far as to suggest the Guam option, first proposed on this blog almost four years ago.

In the first nine days of the month, before the article came out, nine U.S.-affiliated Iraqis were rejected for entry and zero were approved. In the week after the article, thirty-nine were rejected and thirty-one were approved. The good news is that the pace of decisions increased. The bad news is that it remains excruciatingly slow, and the rate of rejections is high—strangely high. Consider that, in order to work in the Green Zone and on military bases, these Iraqis already passed background checks that many of the people reading this post would probably fail. They are, in the words of Kirk Johnson, founder of The List Project, "the most heavily documented refugees on the planet."

Here's another troubling number: over the past few years almost thirty thousand such Iraqis have applied for a Special Immigrant Visa, specifically created by Congress to expedite their cases. Yet only four thousand have been processed, and of these a third have been denied.

And one more figure: until February of this year, the U.S. approved over eighty per cent of all Iraqi applicants—not just former U.S. employees—referred by the U.N. for resettlement here. Since February—when the government put in place a new "security screening" regime—the number has dropped to around fifty per cent.

What's going on?

In May, two Iraqis (who hadn't worked for the U.S. and didn't come here on Special Immigrant Visas) were arrested in Kentucky on charges of plotting to ship weapons to insurgents in Iraq. Perhaps the Iraqi couple were already on the authorities' radar when the new screening was put in place in February. Perhaps there are others on the government's radar now. Whatever the case, it's clear that, because of possible risks and threats, a process that was already troubled and inadequate has almost come to a dead stop.

The Kentucky case has spooked the agencies and removed any incentive for jittery officials to do right by the Iraqis who, at unbelievable risk to themselves and their families, supported the U.S. during the long years of war. The new screening process, like so much of the security apparatus put in place since September 11th, will create moral shame and injustice without making the country any safer. Forget the numbers—there's nothing abstract about this issue. The following stories come from Becca Heller of the Iraqi Refugee Assistance Project:

An elderly, wheelchair-bound Iraqi woman and her two daughters, who had been initially granted refugee status, were recently pulled off a U.S.-bound flight before it left Amman, then deported from Jordan to northern Iraq—simply because they had run afoul of a technical provision in the new screening regime.

A woman who worked on a U.S. base in Baghdad, and is now a refugee in Syria, applied for an S.I.V. last fall. At around the same time, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. She had her final interview at the U.S. embassy in late March, and has heard nothing since—and now she urgently needs a mastectomy.

Another woman who interpreted for the Army first applied for an S.I.V. in 2008. She had her final interview in April. Among the many glitches that delayed her case was the inadvertent removal of her daughter from the application. This woman is currently hiding in Syria.

Multiply these brief stories by the thousands, and you have one of the most disgraceful legacies of the decade since September 11th—a scandal that has only grown worse during the Obama years.

July 12, 2011

Iraqis Pass the Safety Test

At a baseball game in Texas, a father reaches for a tossed ball, flips over a safety rail, and falls to his death before the eyes of his six-year-old son. On the Volga River in Russia, a mother fights her way out of a sinking pleasure boat and loses her grip on the hand of her ten-year-old daughter, who joins dozens of other children in the depths.

Nolan Ryan, owner of the Texas Rangers, said that the rails had passed the safety test and there were no immediate plans to change them. Ryan added, "I think what baseball has done is they want to try to make the experience at the ballpark as memorable as possible for our fans and for them to connect as much as they can with our players. I'm no different than our fan base. When I was younger and went to the ballpark, my hope was to get a foul ball. We're about making memories, about family entertainment and last night we had a father and a son at the game and had a very tragic incident. It just drives to the core of what we're about, and the memories we try to make in this game for our fans." What does this mean? I can't tell and don't want to know, but it proves that Ryan, a pitching legend, was wise to let his arm do the talking during his twenty-seven-year career. In Moscow, Dmitry Medvedev, the Russian President, was more direct: "We have far too many old ships sailing our waters. Just because up until now nothing had gone wrong did not mean that this kind of tragedy could not happen. It has happened now, and with the most terrible consequences." If this sounds startling, it's because we're not used to officials talking without regard to ridicule and lawsuits.

These were not "acts of god," but the culpability is diffuse. The Rangers could have raised the rails after previous incidents. The Russians could have docked their unseaworthy vessels. Both tragedies were freakish and also, in their way, preventable, but now it's too late. You don't have to be a parent to find them intolerable, but it helps.

Meanwhile, the news from Iraq is that a man who risked his life to work as an interpreter for the American military is denied a U.S. visa despite a dozen letters from officers testifying to his bravery and decency. No reason given, which, when you think about it, is worse than a statement from Nolan Ryan. This interpreter is far from alone. A few years ago, Congress mandated that five thousand special immigrant visas be issued annually to Iraqis and Afghans with ties to the U.S. government. So far this year, the number actually issued is around two hundred and forty; in June, zero. Perhaps because of charges against an Iraqi couple in Kentucky, the gates, having been pushed slightly open for a few years, have all but closed. Which is about where things stood back in 2007, when people first started calling attention to this scandal. Tim Arango's story in the Times makes very familiar reading.

I'm also familiar with the official reason: security. This was the official reason in 2007, and 2008, and 2009. It's like being told that the rails met the safety code. I also understand the non-official reason: this issue helps nobody but the Iraqis concerned, gets no one elected, is the lowest possible priority for most harried and worried bureaucrats, and could be detrimental to someone's career if things happen to go wrong. Does it matter that there are good people inside government, in the White House and the State Department, who care about the issue? If the number of visas is zero, then I can't see that it makes much difference. In my experience on this issue, the only thing that makes a difference is leadership—and if it comes from the top, then all the better.

So here is another preventable tragedy for which culpability is diffuse. But unlike the ones in Texas and Russia, the one in Iraq is ongoing. In a sense, it has not even happened yet, not to its fullest extent. This means that, unlike Nolan Ryan and Dmitry Medvedev, President Obama has the good fortune of still being able to save some lives. But not for long. An Iraqi who works for the U.S., and who spent the month of May in hiding after getting a threat, told Arango that, after the last American units leave later this year, "it's going to be the worst time for those people who worked for the Americans." This man has been waiting on his visa request since 2009. And yet the Obama Administration has done no reckoning, no list-gathering, no contingency planning. Just as time runs out on these Iraqis, the doors have slammed in their faces.

In the next few years, American soldiers will also leave Afghanistan, where this issue has been almost ignored. Not long ago, I got a letter from a doctor whose best friend from med school is deployed with the Air Force: "He's having a bit of a tough time over there—most of his cases are Afghan civilians and many of them are kids caught in the crossfire. This is tough stuff even for jaded doctors and soldiers, as you know from covering this stuff. He was also telling me about a rash of cases where the Taliban has been executing people they suspect of being collaborators in bullet-to-the-back-of-the-head fashion. In one case he was actually able to save a young man, but was struggling with what will become of this neurologically impaired man when the U.S. is gone in a year or two."

June 23, 2011

Goodbye to a Kind of War

At the core of President Obama's Afghanistan strategy there's always been a tension, if not an outright contradiction, between means and ends. The goal has always been to destroy Al Qaeda, but the path to Al Qaeda led through the Afghan state and people. Because of the dense interconnections between militant groups in the Hindu Kush, and because Afghanistan once served as host to a much healthier and more dangerous Al Qaeda, Obama concluded that the global jihadists couldn't be fought in isolation, with drones and Special Forces. We had to go after the Taliban as well, for the Taliban threatened the very existence of the regime in Kabul. So to fight terrorism we had to fight insurgents: counterinsurgency was the means, counterterrorism the end. That's why the surge troops went to Kandahar and Helmand, not the Afghan-Pakistan border, and into population centers rather than remote areas. That's why agriculture and legal experts were recruited and sent out into rural Afghan provinces. That's why an entirely new office was created, under the late Richard Holbrooke, to coordinate all the civilian efforts in Afghanistan. That's why an anti-corruption office was established in Kabul. No one in Washington wanted to use the phrase "nation-building," but that's what we were doing—or trying to do, and, honestly, without much success.

In his speech last night in the East Room, Obama tacitly declared a solution to this problem of means and ends. The ends won. Vice-President Biden's view won. That's what matters, more than the timing and the troop numbers. Regardless of the health or sickness of Afghan institutions, we will no longer use counterinsurgency to achieve the goals of counterterrorism. The troop drawdown this year and next signals not so much that "the tide of war is receding," but that America will no longer fight a particular kind of war—soldiers on wary foot patrol in dense neighborhoods and villages, junior officers taking off their helmets and sitting down over tea with local elders to talk about roads and jobs, generals and diplomats alternately coaxing and browbeating their counterparts about troop training and corruption. We've been fighting this kind of war somewhere or other for almost a decade, and Americans, who prefer our wars big on weaponry, short, and decisive, are tired of it, and so, no doubt, is President Obama, as well as many of his Republican opponents and members of Congress. The aggressive campaign against the Taliban over the past year, and the killing of Osama bin Laden last month, provided the natural turning point. After the brilliant raid in Abbotabad, it was inevitable that this announcement would come, and that the President would say, as he did last night, "America, it is time to focus on nation-building here at home." And, he might have added, killing militants in Pakistan with drone strikes and the occasional raid.

Obama's heart was never in Afghan nation-building, but he accepted the argument of his civilian and military advisers that the Taliban couldn't be allowed the chance to return to power. At the moment, that seems unlikely. But the Afghan government—with the possible exception of its army—is no closer to having the support of the people than it was two years ago. The militant networks along the Afghan-Pakistan border are still interwoven with the global jihadists. Afghanistan's recent history suggests that a renewed civil war is quite possible. The means-ends problem wasn't a strategic folly or thoughtless mistake—it was a recognition of the difficulty of finding a long-term solution to the instability and extremism that flourish primarily in the Pashtun regions of south-central Asia. This problem hasn't disappeared with the corpse of Bin Laden. Obama's announcement last night reflects a realistic sense of where our country is and what it can do. The fundamental change is here—not there.

Photograph: Obama in the Blue Room of the White House, April 28, 2011. Official White House Photo by Pete Souza.

May 1, 2011

Osama Bin Laden: Better Late Than Never

It came almost a decade late, after far too many subsequent deaths, some necessary but most of them needless. Nor does it bring to an end anything other than the living embodiment and inspiration of Islamist terror. Still, the killing of Osama bin Laden is cause for deep satisfaction. The President, in his announcement, used the word "justice" several times. Yes, in part—because Osama would not be captured to face official judgment. (We should be grateful, given the way military law has turned the trials of lesser Al Qaeda figures into self-inflicted wounds.) But a completely honest explanation from President Obama would also have mentioned revenge.

It came almost a decade late, after far too many subsequent deaths, some necessary but most of them needless. Nor does it bring to an end anything other than the living embodiment and inspiration of Islamist terror. Still, the killing of Osama bin Laden is cause for deep satisfaction. The President, in his announcement, used the word "justice" several times. Yes, in part—because Osama would not be captured to face official judgment. (We should be grateful, given the way military law has turned the trials of lesser Al Qaeda figures into self-inflicted wounds.) But a completely honest explanation from President Obama would also have mentioned revenge.

Which doesn't diminish the significance or rightness of this action. I wish it had happened at Tora Bora, at the end of 2001. The years since have been a series of almost unrelieved setbacks and disasters for the United States, while Osama himself was practically forgotten. But Americans, along with many others, needed to see this man dead. And now he is—and better still, killed in close quarters, by skillful and courageous soldiers, rather than by remote control from the sky or kidney failure.

Back on the night of September 11th, there were celebrations in the streets of many Arab cities. I doubt there will be many protests this morning, except perhaps in Pakistan. In Morocco, they're demonstrating against Al Qaeda, whose affiliate in the Maghreb just killed sixteen people in a Marrakesh cafe. Arabs have their eyes on their own governments these days, and that is one sign of the way the world has changed since 9/11. Al Qaeda, holed up in the Pakistani tribal areas, saw its operational importance decline under military and intelligence pressure; the global movement fractured into dozens of franchises, each one caught up in and feeding off of local troubles. The main victims of Al Qaeda-licensed terror became impoverished Iraqi Shiites, Jordanian wedding parties, Pakistani police cadets, European train passengers. I never heard any American denounce bin Laden—or his follower Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of Al Qaeda in the Land Between the Two Rivers—more bitterly than the people I heard in Baghdad. Al Qaeda lost its hold on the sympathies of all but a small minority of Muslims, even as the U.S. made itself deeply unpopular. Then came this year's revolts across North Africa and the Middle East, and suddenly it became clear that much of the Muslim world had left 9/11 far behind. Neither Al Qaeda nor Washington matters very much these days in Cairo, Misurata, or Dara'a, and that is good news.

Meanwhile, Pakistan, for reasons of America's counter-terror campaign in its territory and of its own political culture, is going in the opposite direction: sinking into greater militarization, intolerance, and xenophobia. Recently Hillary Clinton and Admiral Mike Mullen complained publicly that the Pakistani authorities were doing far too little to help the U.S. in its openly secret war against Al Qaeda. From the President's speech, it's hard to know whether Islamabad coöperated in the operation at all, or was even informed in advance. Bin Laden was hiding not in the remote tribal mountains, as everyone suspected, but an hour's drive north of Islamabad, in a town with a strong military presence, which makes it impossible not to think that he was living under the protection of Pakistani intelligence. For Pakistani military and intelligence, such a strike under their noses is a humiliating rebuke. Among the public, the death of Osama, a fabulously wealthy Saudi, will probably rouse more anger among poor Urdu and Pashto speakers in Lahore and Peshawar than among Arabs.

If the killing won't do anything to improve America's deteriorating relations with Pakistan, it will force a difficult question on the ten-year-old war in Afghanistan. The President has always insisted that this war's goal is to "disrupt, dismantle, and defeat Al Qaeda." If so, then bin Laden's death should bring us closer to an ending. But I've never fully understood or accepted this rationale for a war where the fighting and nation-building are happening in places like Helmand and Kandahar. The means and the ends have never been in sync. Now, I wouldn't be surprised if the President uses the death of bin Laden to justify accelerating America's disengagement from a conflict for which he's never felt much enthusiasm, regardless of the state of hostilities between the vicious Taliban and the venal Afghan government—which is what the war is mainly about.

When Obama took office, Dick Cheney wasted no time to accuse him of putting America's security at risk—a libel quite unprecedented at that level in recent American history, and one quickly taken up by conservative media. Now the President can claim to have achieved what his predecessor, given almost eight years and every motivation, could not. We will probably learn that the action involved a fair amount of luck—Presidents have little to do with intelligence tips emanating from the ends of the earth. But that doesn't really matter. It won't stop the charges of softness from flying, as they surely will if this news brings a retaliatory attack on New York, Washington, or another American target. But, for most Americans, the killing of Osama bin Laden is the equivalent of a long-form birth certificate in establishing Barack Obama's bona fides as commander-in-chief.

Photograph by Mazhar Ali Kahn/AP.

George Packer's Blog

- George Packer's profile

- 481 followers