Stavros Halvatzis's Blog, page 7

May 13, 2023

The catalyst scene(s)

Solving of the math problem in Good Will Hunting is a fine example of a catalyst scene.

Solving of the math problem in Good Will Hunting is a fine example of a catalyst scene.Linda Seger describes the catalyst scene as one that sets the story in motion. Some refer to this scene as the inciting incident, but this may be a little confusing if not positioned early, as I shall explain below.

The first catalyst, or inciting incident as some may say, occurs within the first ten or fifteen minutes in a film. Seger gives us the following examples: The death of the gladiator’s wife in Gladiator, the quitting of the job in American Beauty, the solving of the math problem in Good Will Hunting or the shooting in Saving Private Ryan.

Seger makes the point that strong catalysts ought to emerge through actions and events rather than unfold through long verbal exchanges. Although a catalyst most commonly occurs in the first half of Act One they may occur throughout the script. For this reason I prefer not to refer to the catalyst as the inciting incident.

“A catalyst scene is a call to action.”Seger provides further examples: Let’s say two people meet at the first turning point in Act One, and as a result fall in love. Or, say, in Act Two a detective uncovers an additional clue which leads him to change his approach to an investigation. Or, perhaps, at the midpoint a protagonist learns about a new drug which might cure her of her cancer. All these bits of information serve as catalysts which initiate subsequent actions that propel the story forward.

Summary

The catalyst scene is a spur to action initiating a series of cause-and-affect events in a story.

Catch my latest YouTube video here!

Tweet

The post The catalyst scene(s) appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

May 6, 2023

The Character Triad

What is the Realisation-Decision-Action character triad and how does it help you write your characters?

The triad focuses on character development, and while, dialogue and plot are important in helping to conjure up the magic in a story, it is convincing character action that keeps the tale moving. That’s where the realisation-decision-action triad comes in. It is a game-changer for creating memorable and believable characters. Here’s how it works.

At its core, the triad reveals how a character responds to a problem or event in a story. First, the character has a realisation – they identify the problem and gain insight on how to solve it. Then, they make a decision about how to act on that realisation. Finally, they take action.

“The character triad combines a realisation and a decision of how to solve a problem with the action itself, rendering the action authentic and convincing.Let’s take a look at how this works in one of the greatest TV shows of all time – Breaking Bad. In episode 6 season 3 Walter learns that Hank is close to discovering Walter’s link to Jesse by locating the RV meth lab. Here’s how the triad plays out:

Realisation – Walter realises that Hank is on his trail and is about to uncover his identity.

Decision – Walter decides to have the RV destroyed before Hank can find it and connect it to him.

Action – Walter rushes to Clovis’s lot where the RV is located and decides to have it pulverized in a nearby junkyard.

But of course, it’s never that simple. Jesse learns/realises that Walter is about to destroy the RV and decides to try and prevent this. He rushes to the junkyard, leading Hank, who has been following him, straight to the RV and to Walter.

Unable to get away without being spotted, Walter and Jesse lock themselves inside the RV in a blind panic.

What happens next? You’ll have to watch the episode to find out!

So, there you have it – the realisation-decision-action character triad on a roll!

Summary

The function of the character triad is to establish a cause-and-effect relationship between the characters’ thoughts, decisions and actions.

Catch my latest YouTube video through this link!

Tweet

The post The Character Triad appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

April 29, 2023

The Decision Scene

The decision scene is in full displays in Stand by Me.

The decision scene is in full displays in Stand by Me.Are you struggling to make your story feel authentic and engaging? Then look no further! One of the keys to powerful plots lies in mastering how to craft the realisation-decision-action scene triad, as humans are wired to think and act in this order.

According to Linda Seger’s Advanced Screenwriting, not inserting a decision scene between a realisation scene and an action scene can make the story appear forced, disconnected from the plot, and without depth. A decision scene provides the reasoning and motivation behind a character’s actions, making them feel more genuine and relatable.

Think of Chuck Nolan discovering the plastic door in Castaway, or Vern and the boys deciding to investigate the dead body in Stand by Me, or the nurse in The English Patient making the decision to stay behind. These decisions lead to significant plot development and create an air of authenticity that draws the audience in.

“A decision ought to follow a realisation and lead to action showing the outcome of that decision.”A decision, then, involves a character or characters inspecting, investigating, questioning or simply observing, before coming to a decision. This leads to action being taken directly after as a result.

So, if you want to take your story to the next level, make sure to include a decision scene between the realisation and action scenes.

Summary

A decision scene follows a realisation and provides the reason for the action that follows it. It grants your story verisimilitude.

Catch my latest YouTube video here!

Tweet

The post The Decision Scene appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

April 22, 2023

The Confrontation Scene

The confrontation scene in American Beauty.

The confrontation scene in American Beauty.In her book, Advanced Screenwriting, Linda Seger explains that the confrontation scene is one which uncorks the pressure that has been building up in the story between characters.

It is typically about one character’ s anger or dissatisfaction directed at the wrongs, real or imagined, perpetrated by another against him or her. The time for hints and innuendos has passed. This scene allows a buried truth to be uncovered. Here the subtext finally explodes to the surface. In the words of Seger, this is the scene where a character ‘tells it like it is.’

In the film American Beauty Lester confronts the lies in his life. He desperately needs more from his job, his sexuality. And he needs something deeper from his wife who elevates her job and the couch above the meaningful things in life. Here is Lester’s confrontation with her about the gulf between them stemming from her shallowness and confused values.

LESTER: Carolyn, when did you become so joyless?…This isn’t life. It’s just stuff. And it’s become more important to you than living. Well, honey, that’s just nuts.

Lester’s words are not overly angry or numerous, but their import is devastating.

Sometimes the confrontation scene is anticipated, which builds tension. At other times it is unexpected although the reader or audience has sensed that it is coming.

In the film Tootsie, Michael confronts his agent for not informing him about an audition for a play. The agent suggests that Michael’s problems have made him essentially unemployable. The scene exposes Michael as being in need of therapy.

Summary

The confrontation scene is typically one where the subtext bursts to the surface, where one character confronts another about a wrong perpetrated against him, whether real or imagined.

Catch my latest YouTube video here!

Tweet

The post The Confrontation Scene appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

April 8, 2023

Revealing backstory

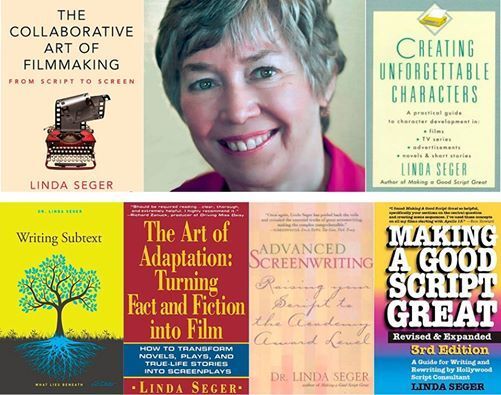

Linda Seger talks about revealing backstory.

Linda Seger talks about revealing backstory.In her book Creating Unforgettable Characters, Linda Seger wraps-up her chapter on creating and revealing a character’s backstory in this way (I paraphrase her here):

Creating backstory should be a process of discovery. The writer ought to keep asking questions about a character’s background in a back-and-forth fashion in order to explain or support that character’s motivation for their action. When the writer is in the flow, the information seems to reveal itself rather than be imposed by brute force through specific formulas. The result is a process of expanding, enriching, and deepening a character in an organic and effortless way. To help us in this process, Seger suggests that we ask these questions as we write:

“Revealing backstory in an adroit way is indispensable to the crafting of accomplished stories.”Is my work on backstory a process of discovery? In other words, do I let the character’s backstory unfold naturally as needed rather than imposing excessive detail on the character in a way that may not be relevant?As I reveal backstory, am I careful not to show more than the bare minimum needed for a character to carry the moment?Am I layering the information throughout the story, not lumping it all into info-heavy speeches?Am I revealing information in the shortest, most economical space possible? Am I able, for example, to reveal bits of backstory in a single sentence, with the help of subtext, so that the attitudes, motivations, emotions, and decisions of characters are revealed?Although not replete, this bit of advice will improve your ability to fashion a character’s backstory in a more economical and flowing way.

Summary

Ask a series of questions to help you create an economical and organic approach to writing and revealing backstory.

Catch my latest YouTube video here!

Tweet

The post Revealing backstory appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

April 2, 2023

About character

It’s all about character – the subject of Linda Seger’s book.

It’s all about character – the subject of Linda Seger’s book.In her book, Creating Unforgettable Characters, Linda Seger advises writers to be on the look-out for opportunities to extract and store details from the people and world around us.

Our stories should spring from reality but be developed through our imagination according to the requirements of the genre we are working in—fantastical creatures as in the Harry Potter books and movies, or straight-forward people as in any drama or crime thriller.

In summarising her Chapter Two on how to start to create a character Linda Seger quotes the writer Barry Morrow who characterises the process in this way: “It’s like shaping a lump of clay, or whittling a stick. You can’t get to the fine stuff until you get the bark off.”

“It’s all about character. Knowing where to begin is half the battle.”Here is how Seger summarises her chapter:

Through observation and experience, you begin to form an idea of a character.The first broad strokes begin to define the character.You define the character’s consistency, so the character makes sense.Adding quirks, the illogical, the paradoxical, makes the character fascinating and compelling.The qualities of emotions, values, and attitudes deepen the character.Adding details makes the character unique and special.Summary

Plots without interesting and unique characters to drive them fall flat – ultimately it is all about character.

Catch my latest YouTube video here!

Tweet

The post About character appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

March 25, 2023

Start late, end early.

Akers on how to start late and leave early.

Akers on how to start late and leave early.One of the most common errors inexperienced writers make is to write scenes that start early and end late. There’s just too much fat at both ends, especially in a screenplay, where every unnecessary line costs hundreds if not thousands of dollars to shoot.

One way to eliminate unnecessary material is to concentrate on the gist of your scene. What is it that you want to convey through your character actions and dialogue? Do so and move on!

In Your Screenplay Sucks, William M Akers provides this example of how to cut a scene to the bone. An earlier draft looked like this:

———————

INT. GRAHAM’S SEVEN PAINTINGS.

Huge, nearly abstract canvases of bloody, dead, eviscerated animals. Road kill under a layer of sloppy handwriting. Graham poses with Magda, more photos.

Magda departs. Camilla approaches.

CAMILLA

I’m Camilla Warren. Nice night.

They shake hands, slowly. She is very appealing.

GRAHAM

Buying, or watching?

CAMILLA

Watching.

She inspects him.

CAMILLA

Sold anything?

GRAHAM

I will.

CAMILLA

When you do, find me.

And she’s gone.

————————-

Here’s how the scene ended up:

INT. GRAHAM’S SEVEN~ PAINTINGS

Huge, nearly abstract canvases of bloody, dead, eviscerated animals. Road kill under a layer of sloppy handwriting. Graham poses with Magda, more photos.

Magda departs. Camilla approaches.

CAMILLA

Sold anything?

GRAHAM

I will.

CAMILLA

When you do, find me.

And she’s gone.

—————————

So, there you have it. To start late and end early means to get to the point. This entails getting rid of unnecessary diversions, greetings and niceties since they slow the pace and muddy the story.

Summary

Scenes should start late and end early. Your story will be more compelling and energetic for it.

Catch my latest YouTube video here!

Tweet

The post Start late, end early. appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

March 19, 2023

Become a Master of Emotion in Writing

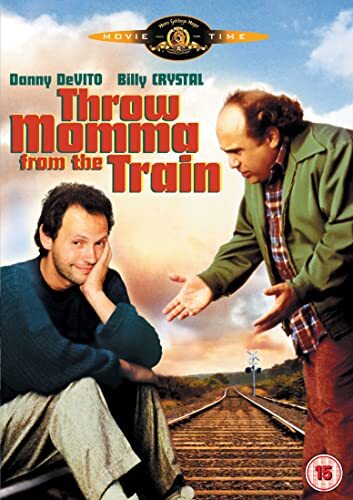

Throw Mama from the train showcases masterful emotion in writing.

Throw Mama from the train showcases masterful emotion in writing.Here is a masterful example, taken from William M. Akers’, Your Screenplay Sucks, of how to set up a scene in order to create genuine and powerful emotion—in this case, tear-jerking compassion!

In Throw Mama from the Train Larry Donner, played by Billy Crystal, is roped into attending dinner at Owen’s house. Owen (played by Danny DeVito) lives with his mother. He is Larry’s worst writing student at the community college where he teaches. Owen is a rather simple-minded, talentless, irritating imp of a man who lives with his mother, a cantankerous old woman with a painful voice and an even worse personality. We learn that Danny’s father is dead.

The dinner is terrible, Owen is as irritating as ever and his mother is just plain horrible. ‘Owen, you don’t have any friends,’ she rasps, stating the obvious. Larry desperately wants to leave, heck, we want him to leave, but he seems stuck there out of an abundance of politeness.

Up to now, the scene has made us uncomfortable, generated feelings of confinement, of being trapped in a hostile and hopeless environment. We shift in our seats and pray for it to end.

Finally the mother goes off to bed. Here is Larry’s chance to escape! But no. Owen asks Billy if wants to see his coin collection, and Billy is forced to say yes, again out of politeness.

“Knowing how to evoke emotion is the single most important skill to master in story-telling.”Up to now, we have come to dislike Owen, well, for being Owen, and for putting Larry through such an excruciating evening. Not much to like here.

Then Owen dumps several coins on the floor—a few worn out quarters, some old dimes and nickels. So that’s it? This is his magnificent coin collection?

Then this happens: I’ll quote Akers who quotes Owen’s exact words from the scene: ‘ “This one here, I got in change, when my dad took me to see Peter, Paul, and Mary. And this one, I got in change when I bought a hot dog at the circus. My daddy let me keep the change. He always let me keep the change.” ‘

Wow! What a shift in our emotions—not a dry eye in the house! We’ve gone from loathing Owen to loving him through this sudden injection of feeling rooted in his nostalgia for his past life with his father. It explains why, in a certain sense, the child-like Owen stoped growing beyond the days spent with his father. He is still irritating, but now we understand him a little more, and we adore him for it; perhaps we even feel a little guilty for having loathed him in the first place.

This is masterful writing. Well done to the screenwriter, Mr Stu Silver!

Summary

Knowing how to evoke emotion in writing is the single most effective thing you can do to improve your stories.

Catch my latest YouTube video through this link.

Tweet

The post Become a Master of Emotion in Writing appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

March 11, 2023

Understanding the dual function of Archetypes

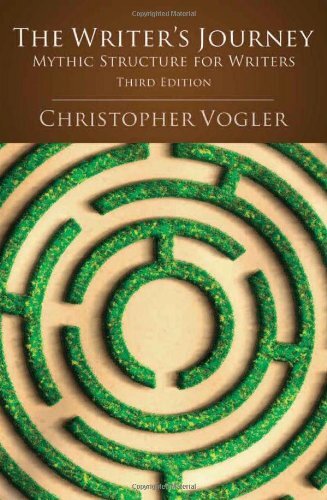

Christopher Vogler on the dual function of archetypes.

Christopher Vogler on the dual function of archetypes.In a previous post I talked about the dual function of archetypes as presented by Christopher Vogler in his book, The Writers Journey, namely a dramatic and a psychological function. This deserves further explaining.

The dramatic function of an archetype, such as the Hero, is to display behaviour in a way that drives the story forward, but also in a way that pulls readers and audiences into the drama.

Heroes finds themselves in a position where they have to solve a local or societal problem, and to do so in an intriguing and captivating way, if the tale is to succeed. This comes down to the writer employing good dramatic principles such generating suspense, placing the hero before a dilemma, having him or her struggle to master difficult skills, go on a journey of self-discovery, and the like.

“The dual function of archetypes offers the writer a complete system of managing character behaviour.”The psychological function of an archetype, on the other hand, demonstrates how the hero can achieve success though a process of integration, to use Carl Jung’s term. But integration of what, you may well ask?

Simply stated, the integration of the remaining archetypes, or to put it in another way, through the integration of the energies that dwell within the Self, primarily the Shadow (the dark energy within us all), but also the Mentor, the Herald, the Threshold Guardian, the Shapeshifter, the Ally, and the Trickster. It is only when the Hero knowledges these energies within, then manages to achieve a balance between them, that he can overcome the physical challenges in the world.

A story, then, can be seen as the projection on the pages of book or the surface of a screen of the energies struggling for balance within one’s self—as the externalisation, the dramatization, the playing out of these forces. Understood in this way, Christopher Vogler’s archetypes offer a complete system of writing stories that arise from myth, our collective unconscious, and our deep literary traditions. They are about ourselves as much as they are about the world.

Summary

The dual function of archetypes includes not only the dramatic dimension of stories but the psychological remnants found in humanity’s collective unconscious that form the basis of our rich, mythic traditions.

Catch my latest YouTube video here!

Tweet

The post Understanding the dual function of Archetypes appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

March 4, 2023

How to introduce characters in a screenplay

What a way to introduce characters!

What a way to introduce characters!In his book, Your Screenplay Sucks, William M Akers admonishes us to introduce characters in our screenplays in a concise but telling way. He provides the following counter example:

“MURIEL REED, a grounds Keeper, captivates Gary. She fills the sprayer with soda and mists brown over the grass.” This is perhaps a little too scanty. Akers suggests that you tell us about a character’s personality, their flaws or tics, but hold back on the smaller physical details until they are of importance. He suggests that specifying race and height, unless truly relevant, is best left out.

“When you introduce characters for the first time in the action block of a screenplay avoid superfluous physical details. Hone in only on details that provide a snapshot of personality.”

It is better to include physical detail that characterises—does double duty. Here’s an extract from Good Will Hunting:

“The guy holding court is CHUKIE SULLIVAN, 20, and the largest of the bunch. He is loud, boisterous, a born entertainer. Next to him is WILL HUNTING, 20, handsome and confident, a soft-spoken leader…”

From Ghostbusters:

“Venkman is an associate professor but his rumpled suit and manic gleam in his eyes indicate an underlying instability in his nature.”

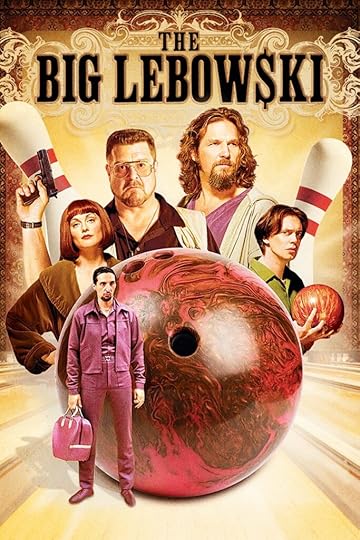

This example, from The Big Lebowski, is Akers’ favourite:

“It is late, the supermarket all but deserted. We are tracking in on a fortyish man in Bermuda shirts and sunglasses at the dairy case. He is the Dude. His rumpled look and relaxed manner suggest a man in whom casualness runs deep.”

There you have it. A no nonsense approach of how to introduce the characters in your screenplays from one of the best.

Summary

Introduce characters by highlighting some quintessential aspect of their identity. Avoid superfluous details.

Catch my latest YouTube video here!

Tweet

The post How to introduce characters in a screenplay appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..