Stavros Halvatzis's Blog, page 39

November 5, 2016

Potent Language in Stories

SOME of the most potent writing advice comes from Strunk and White’s brief but perennially precious book, Elements of Style. In the chapter, Principles of Composition, we learn to ‘prefer the specific to the general, the definite to the vague, the concrete to the abstract.’

SOME of the most potent writing advice comes from Strunk and White’s brief but perennially precious book, Elements of Style. In the chapter, Principles of Composition, we learn to ‘prefer the specific to the general, the definite to the vague, the concrete to the abstract.’

Writers who seize and hold the reader’s attention by being definite, specific, and concrete number amongst the greatest – Homer, Dante, Shakespeare. Their writing is potent, in part, because their words render up pictures.

Here is an extract from The Zoo from a short story by Jean Stanford, a lesser known but nonetheless accomplished writer:

Potent Language

‘Daisy and I in time found asylum in a small menagerie down by the railroad tracks. It belonged to a gentle alcoholic ne’er-do-well, who did nothing all day long but drink bathtub gin in Rickey’s and play solitaire and smile to himself and talk to his animals. He had a little stunted red vixen and a deodorized skunk, a parrot from Tahiti that spoke Parisian French, a woebegone coyote, and two capuchin monkeys, so serious and humanized, so small and sad and sweet, and so religious-looking with their tonsured heads that it was impossible not to think of their gibberish was really an ordered language with a grammar that someday some philologist would understand.’

This is a powerful evocation of an environment, a personality, indeed, a world, and all done through the telling use of concrete and specific language. This language is not only useful in evoking an appropriate atmosphere in short stories and novels. It is also important when used adroitly in the ‘action block’ of screenplays, where brief, specific, and concrete language adds to the precise direction needed by actors, set designers, and set dressers to render scenes effectively.

Summary

Use specific, definite, and concrete language to write scenes that create mood and render up potent pictures in the minds of your readers.

Tweet

The post Potent Language in Stories appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

October 29, 2016

Cooking Your Story

Cooking

WRITING is much like cooking. You select your ingredients and mix them in a way that you hope will yield a satisfactory experience.In teaching story structure I often talk about the importance of the turn, and how it helps to keep your readers engaged through the element of surprise. By definition, this involves revealing new information that your readers did not anticipate.

But apart from the element of surprise, what other ingredients are baked into turns? How are turns related to one another, if at all? Here are three suggestions.

Cooking your story

The first thing to note is that a turn is most often caused by an unexpected obstacle in the protagonist’s path to the goal. In my novella, The Nostalgia of Time Travel, for example, the protagonist, Benjamin Vlahos, is told that a woman who resembles his dead wife, Miranda, has been enquiring about him in the Australian resort town of Mission Beach. This comes out of left field for Benjamin and spins the story around in a different direction.

Secondly, each turn should occur at a higher pitch than the one preceding it. As the stakes mount, new challenges bring higher risks to the hero and his world. Staying with The Nostalgia of Time Travel: As if an approaching category-five cyclone and an impossible appearance by his dead wife are not enough, Benjamin is paid a ghostly visit by his long dead uncle, whom, he is convinced, he killed through a spiteful prank when he was a boy. The experience is enough to have Benjamin contemplate ending his life.

Thirdly, for most of the story, the hero’s response to these obstacles is insufficient to gain him the goal, until the final climax, when he can finally absorb and integrate the lessons stemming from his defeats. At the climax of Nostalgia, Benjamin is faced with a choice. He can give up on life and let the cyclone take him, as his uncle’s apparition will have him do, or he can integrate, into his current life, his new understanding of a secret his parents kept from him and let that steer him in a new direction.

Surprise, pitch, integration. These are three important ‘turn’ ingredients involved in the cooking of your word soup. Use them liberally to add spice to your stories.

Summary

Cooking in obstacles and rising stakes increases the tension in your story. Write the ‘ah-huh’ moment as your hero finally integrates his actions with the lessons learnt.

Tweet

The post Cooking Your Story appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

October 22, 2016

How to Twist Your Story’s Spine

THE twist is an important moment in any story. Indeed, I often think of a story’s spine as a zig-zagging line that resembles a thunderbolt thrown down by Zeus. It has energy and surprise encoded into its very structure.

THE twist is an important moment in any story. Indeed, I often think of a story’s spine as a zig-zagging line that resembles a thunderbolt thrown down by Zeus. It has energy and surprise encoded into its very structure.

And so it ought to.

But how do twists work? How many of them are there, and what, exactly, is a twist anyway?

The short answer is that the twist is a sudden turn in the hero’s path to the goal so that it now points in a new direction, based on the significance of new information that confronts him.

Here is one list of events that may be regarded as twists:

There’s a Twist in the Tale

1. An unexpected problem derails the hero’s path to the goal.

2. The hero loses an important resource.

3. A sidekick or supporter switches sides.

4. A lie is revealed.

5. A past mistake resurfaces to muddy the waters.

6. The trust in an important ally is lost.

7. An alternative plan emerges to rival the existing one.

8. The hero loses faith in his ability to achieve the goal.

When a twist is severe enough to cause a total change in the original plan, such an unexpected problem derailing the hero’s path to the goal, then that twist is a turning point – one of the two turning points that occur in Syd Field’s rendition of the three-act story structure.

In my novel, The Land Below, for example, Paulie’s discovery that the mysterious machine which supplies power to his underground city has no moving parts, is certainly a twist in the tale it, but it falls short of being a turning point that pivots the story in a different direction.

In The Matrix, however, Neo’s realisation that his life has been nothing more than a simulation fed into his slumbering bran, is a major turning point that spins the story into the second act of this extraordinary movie.

Further, a twist such as the hero’s losing faith in his ability to achieve his goal represents a temporary deviation or pause in his journey. It does not reach the magnitude of a turning point, but is a good candidate for a mid-point, where, typically, the hero questions his strength and ability to pursue the goal.

Other twists, such as a lie being revealed, or a sidekick changing sides, represent deflections to the established path but do not necessarily constitute a derailment.

Although no one can predetermine the precise number of twists in your story beforehand (except for the two major turning points) use them liberally to create a story shape that is interesting and unpredictable.

Summary

Twist and turn your story to help keep your readers and audiences engaged.

Tweet

The post How to Twist Your Story’s Spine appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

October 16, 2016

Writing Powerful Scenes

IN a recent lecture on storytelling I was asked about the general design mechanics of scenes. What sorts of functions must occur in a scene to make it effective – especially a pivotal scene such as one containing a turning point? And how are these functions grouped together?

IN a recent lecture on storytelling I was asked about the general design mechanics of scenes. What sorts of functions must occur in a scene to make it effective – especially a pivotal scene such as one containing a turning point? And how are these functions grouped together?

I find it helpful to organise functions into separate layers. The first two are straight forward. On one level scenes must showcase actions such as the hero’s response to some challenge laid down before him. Actions comprise the so-called outer journey – the plot.

But on an underlying level scenes must also support the plot by showing that the hero’s actions are consistent with his inner journey. In other words, that his motivation arises naturally from his values, beliefs, background.

Additionally, the hero must show personal growth. He must exhibit an ability to learn from the mistakes he makes in pursuing his goal, if he is finally to achieve it.

Involving Readers and Audiences in Your Scenes

These two levels in a scene are indispensable to each other. They really make up a single dramatic unit – action and its motivational core. But there is another layer we can add to a pivotal scene to make it even more effective. We can offer the reader or audience more information than is available to the hero.

If we, as an audience, are aware of something that the hero is not, such as that his is cheating on his wife with her best friend, or that there is a bomb in his car, or that his boss is planning to fire him, then we generate tension which is dissipated only when the hero learns this himself.

Hitchcock is a master of this technique. His films are studies of how to generate suspense by revealing to audiences things that the protagonist has yet to realise.

In my science fiction thriller, The Level, the protagonist, a man suffering from amnesia who is trying to escape from a derelict asylum, is unaware that he is being stalked by someone brandishing a meat clever, a man who bares him a grudge for some past offense. But the reader is, and this generates additional suspense for the protagonist with whom the reader identifies.

Not all scenes and genres are susceptible to this sort of treatment. Sprinkled here and there, however, the technique significantly ramps up tension that keeps our readers and audiences engrossed.

Summary

Reveal more information to your readers and audiences than is known to your protagonist at specific scenes in your story to help spike up the tension.

Tweet

The post Writing Powerful Scenes appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

October 8, 2016

How to Generate High Concept Ideas in Stories

AS a teacher and writer I am often asked to give advice about generating ideas for a screenplay or novel.

AS a teacher and writer I am often asked to give advice about generating ideas for a screenplay or novel.

What sorts of things should the writer look for in a concept to maximise its chance for commercial success?

In the absence of a crystal ball, use High Concept. Here are some of its components:

Ideas Checklist

1. Ensure your story ideas contain high stakes. This sets the stage for a big story – Air Force One (The POTUS is held hostage on his plane, 12 Monkeys – a virus threatens to wipe out humanity.

2. Set your story in a unique or interesting environment – Hart’s War (Nazi concentration camp), Red Corner (Red China).

3. Pick the correct protagonist: Liar, Liar (a lawyer who has to tell the truth for a whole day).

4. Pick a fresh and powerful dilemma: John Q (a father takes the hospital hostage demanding they perform a heart transplant on his dying son).

5. Pick a unique strategy for your protagonist to pursue. Memento: A man who can only remember a few minutes at a time tries to track down his wife’s killer by tattooing his body with key words and instructions.

Of course, a hit depends on your getting so many other factors right too, but using these suggestions does enhance the commercial potential of your story idea.

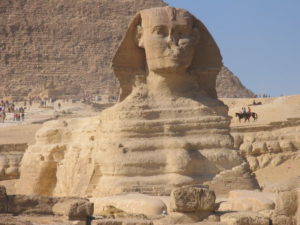

I take my own advice in my own stories. Here’s a short description of my first novel, Scarab, which grabbed the number one bestsellers spot on Amazon.com and amazon.co.uk in its genre:

“Buried in a hidden chamber beneath the great Sphinx of Giza, lies the most potent secret in history. Older than the pyramids, older than Atlantis, it has the ability to change the world. Powerful men will do anything to posses it. There is just one thing standing in their way – the living Sphinx itself.”

The Level was my second novel:

“A man, suffering from amnesia, wakes up in a pitch-black room, tied to what feels like a wooden chair. He discovers he is being held captive in a derelict insane asylum stalked by inmates who are determined to kill him. Help comes in the form of a beautiful, mysterious woman dressed in a black burka who offers to show him the way out, if only he can remember who he truly is.”

Both ideas draw on high concept and make for intriguing reading.

Summary

Use High Concept to make your story ideas more commercial.

Tweet

The post How to Generate High Concept Ideas in Stories appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

October 1, 2016

Writing with Style

ONE of the first things we notice about a writer is her style – the way she arranges the flow of words on paper, indeed, the way she chooses specific words over a myriad of others.

ONE of the first things we notice about a writer is her style – the way she arranges the flow of words on paper, indeed, the way she chooses specific words over a myriad of others.

In Elements of Style, Strunk and White point out that style reveals not only the spirit of the writer, but very often, her identity too. Style contributes to her ‘voice’ – her attitude towards her characters, the world and its ideology.

A matter of Style

By way of example here are two passages by two great writers on the subject of languor. The first is quintessential Faulkner:

“He did not still feel weak, he was merely luxuriating in the supremely gutful lassitude of convalescence in which time, hurry, doing, did not exist, the accumulating seconds and minutes and hours to which in its well state the body is slave both waking and sleeping, now reversed and time now the lip-server and mendicant to the body’s pleasure instead of the body thrall to time’s headlong course.”

Now Hemingway:

“Manuel drank his brandy. He felt sleepy himself. It was too hot to go into the town. Besides there was nothing to do. He wanted to see Zurich. He would go to sleep while he waited.”

The difference in style is striking, yet both passages are effective. The first is loquacious, almost verbose. It underpins the subject matter by evoking slowness, inactivity. The second is brief, laconic, yet its very brevity communicates Manuel’s languor through the truncated, sluggish drift of his thoughts.

How, then, does the new writer develop her own style?

Discovering what sort of writing appeals to you the most might be a first step. Giving yourself time to find and develop your individual voice through trail and error is another. The journey is long and hard, as the saying goes, but the rewards are worthwhile – work that is memorable and unique.

Synopsis

Find you own writing style by identifying and immersing yourself in works you admire. Then put your head down and write.

Tweet

The post Writing with Style appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

September 28, 2016

How to Write Likable Heroes in Films and Novels

In his book, Writing Screenplays that Sell, Michael Hague, emphasises the need to make our heroes likable in order to create audience and reader identification.

In his book, Writing Screenplays that Sell, Michael Hague, emphasises the need to make our heroes likable in order to create audience and reader identification.

Likable heroes make for more successful films and novels. A consistently repellent, unlikable hero is almost a contradiction in terms and usually accounts for the failure of a film at the box office.

Likable Protagonists

Here are three simple but effective ways to achieve likable protagonists:

Make your her a kind, good person, as with the heroes in Norma Ray, or Crimes of the Heart.

Make the hero funny and entertaining, as in Beverly Hills Cop, or Lost in America.

Make the hero tough, or good at what he does, as in Dirty Harry and Lethal Weapon.

Using one or more of these traits (preferably all three) will make your hero more sympathetic and engaging — vital steps in creating identification with the audience.

Additionally, be sure to establish these positive traits as soon as possible – especially if you are dealing with a complex, flawed characters. Only after you have created identification can you begin to reveal their inherent flaws. Once we begin to root for our hero, we are likely to continue to do so, no matter what imperfections we spot in him later on.

Summary

Ensure the heroes in your screenplays and novels display some likable traits, early on, before exposing their flaws.

Tweet

The post How to Write Likable Heroes in Films and Novels appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

September 24, 2016

How to Write Likable Heroes

In his book, Writing Screenplays that Sell, Michael Hague, emphasises the need to make our heroes likable in order to create audience and reader identification.

In his book, Writing Screenplays that Sell, Michael Hague, emphasises the need to make our heroes likable in order to create audience and reader identification.

Likable heroes make for more successful films and novels. A consistently repellent, unlikable hero is almost a contradiction in terms and usually accounts for the failure of a film at the box office.

Likable Heroes

Here are three simple but effective ways to achieve likable heroes:

Make your hero a kind, good person, as with the heroes in Norma Ray, or Crimes of the Heart.

Make the hero funny and entertaining, as in Beverly Hills Cop, or Lost in America.

Make the hero tough, or good at what he does, as in Dirty Harry and Lethal Weapon.

Using one or more of these traits (preferably all three) will make your hero more sympathetic and engaging – vital steps in creating identification with the audience.

Additionally, be sure to establish these positive traits as soon as possible – especially if you are dealing with complex, flawed characters. Only after you have created identification can you begin to reveal their inherent flaws. Once we begin to root for our hero, we are likely to continue to do so, no matter what imperfections we spot in him later on.

Summary

Ensure the heroes in your screenplays and novels display some likable traits from the get-go, before exposing their flaws.

Tweet

The post How to Write Likable Heroes appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

September 17, 2016

In Stories It Is All About Emotions

I have often written about the importance of soliciting emotions in the stories we write.

I have often written about the importance of soliciting emotions in the stories we write.

Yet, the topic is of such monumental importance that I can’t write about it often enough.

Emotions, Emotions, Emotions

In her book, The Novelist’s Guide, Margret Geraghty reminds us that soliciting emotion for the characters in our stories is the single most important thing we need to master. Here’s an extract from Katherine Mansfield’s, The Fly, that has stayed in my memory from the first time I read it.

A fly has fallen into an ink pot and can’t get out. The other character, referred to only as the boss, watches its desperate struggles with glee.

“Help! Help! said those struggling legs. But the sides of the ink pot were wet and slippery; it fell back again and began to swim. The boss took up a pen, picked up the fly out of the ink, and shook it on a piece of blotting paper. For a fraction of a second, it lay still on the dark patch that oozed around it. Then the front legs waved, took hold, and, pulling its small, sodden body up, it began the immense task of cleaning the ink from its wings … it succeeded at last, and, sitting down, it began, like a minute cat, to clean its face. Now one could imagine that the little front legs rubbed against each other, lightly, joyfully. The horrible danger was over; it had escaped; it was ready for life again.

But then, the boss had an idea. He plunged the pen back into the ink, leaned his thick wrist on the blotting paper, and, as the fly tried its wings, down came a heavy blot. What would it make if that? The little beggar seemed absolutely cowed, stunned, and afraid to move because of what would happen next. But then, as if painfully, it dragged itself froward. The front legs waved, caught hold, and more slowly this time, the task began from the beginning.”

This goes on until the fly is dead. If we can feel compassion for a fly, imagine what we can feel for animals and humans.

Emotion can also be present for the reader or audience, but be hidden from a character who may not yet understand it, such as a child. In my novella, The Nostalgia of Time Travel, I use this technique subtly to suggest a sense of unease in the relationship between a mother and her brother-in-law, as experienced through the sensibility of a child:

“One hot afternoon, my father’s older brother, Fanos, a mechanic with the merchant Greek navy, sailed into our lives, without warning, like a bottle washing out to shore. He carried a small black suitcase in his right hand. The hand was stained by a faded blue tattoo of an anchor that started at the wrist and ended at the knuckles. I found myself staring at it at every opportunity.

Would it be fine if he stayed with us for several days, while his ship underwent repairs at the port of Piraeus, he wanted to know?

My father, who seemed both pained and glad to see him, said it would be, if that was all right with my mother. My mother had nodded and rushed out to the backyard to collect the washing from the clothes line. She had trudged back in and made straight for the bedroom where she proceeded to fold, unfold, and refold the clothes. She did this so many times that I thought she was testing out some new game, before asking me to play.”

The boy may not understand the underlying conflict, but we do, and that makes it doubly effective.

Summary

Use the emotions of your characters to bind your readers and audiences to your stories.

Tweet

The post In Stories It Is All About Emotions appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..

September 10, 2016

How to write Nonhuman Characters

We often need to create nonhuman characters in the stories we write – animals, robots, talking trees.

We often need to create nonhuman characters in the stories we write – animals, robots, talking trees.

In Creating Unforgettable Characters, Linda Seger reminds us that human characters achieve dimensionality by highlighting their human attributes.

Highlighting nonhuman attributes of dogs, such as barking louder or digging faster to get the buried bone, will not make them more endearing. To achieve that we must give them human personality.

We need to do at least three things: choose one or two attributes that will help create character identity, understand the associations the audience itself brings to the character, and create a strong story context to deepen the character.

Attributes in themselves do not give enough interest and variety. Audiences need to project associations onto them. Nowhere is this more clearly seen than in advertising.

Reader and Audience Association with Nonhuman Characters

Mercedes is branded as the car of engineering, Ford represents quality, and so on. By associating the car with a certain quality you get the rub-off or halo effect. In advertising this causes the consumer to want to purchase the product. In films and novels the effect draws us closer to the characters through our projecting personal feelings onto them.

In producer Al Burton’s TV series, Lassie, the dog part is written in a way that allows the animal to become part of the family, a best friend to the adults and their son. Through this deft move the series becomes family viewing, and not merely a kid’s show.

A character such as King Kong, however, brings very different associations. He comes from the South Seas. He is enveloped in a dark, mysterious, and terrifying aura. His associations include a vague knowledge of ancient rituals, human sacrifice, and dark, unrepressed sexuality. We, as adults, are frightened of King Kong because we bring to his character our apprehensions of the unknown.

In my novel, Scarab, the Man-Lion, a mythical creature in the likeness of the Spinx of Giza, carries the same sort of frightening mystery and intrigue. Its dark fascination for the reader is generated more by the power of association than a detailed description in the pages of the novel.

Understanding the power of association and how to use it, then, is a crucial part of creating and positioning characters in your stories, and in the market place.

Summary

Highlighting specific human characteristics in nonhuman characters, and using them to amplify our reader’s and audience’s personal experience, helps to make them more engaging.

Tweet

The post How to write Nonhuman Characters appeared first on Stavros Halvatzis Ph.D..