Lyndon Hardy's Blog, page 5

November 16, 2016

Punctuation puzzles

A relatively obscure puzzle category is that of punctuation puzzles. An example is to add capitalization and punctuation to the following list of words to make them grammatically correct – and explain what the result means.

time flies you can’t they move to fast.

The answer is:

“Time flies!”

“You can’t. They move too fast.”

Someone asked a friend to time how fast houseflies move. The friend replied that they darted about too quickly for him to do so.

Corny? Sure. But here’s one that is a little more challenging.

becky while tom had had had had had had had had had had had the teachers approval

I will share the solution in my next post.

© 2016 Lyndon Hardy

October 14, 2016

An untold tale about Richard Fyneman

When I was at Caltech, Richard Fyneman, the renowned physicist, gave a one-hour seminar each week entitled Physics X. It was not in the catalogue. There was no college credit. You just showed up in the lecture hall and Fyneman would ask, “OK, what shall we discuss today?”

He was a great lecturer. With no preparation ahead of time, he would explain some hard to understand aspect of physics that was wonderfully clear. You took notes furiously, because a half-hour or so after leaving the hall, the brilliant insight that you thought you now grasped would begin to fade.

I remember to this day that one time on of us sitting in the audience said something like the following:

“Professor Fyneman, suppose you are in a spaceship going very nearly the speed of light. You are flying parallel to a long mirror extending far into space alongside you. You look out and see your reflection in the mirror.

“Now it take some time, not much, but some time for the light from your spaceship to travel to the mirror and then bounce back to you. This means that the reflection will not be exactly aligned but lag behind slightly. Since you, yourself, are going so swiftly, the angle would be noticable. You would have to crane your neck to see your reflection.

“So by measuring the angle of the lag, you could then figure out how fast you are going, and that would violate Special Relativity.”

“An interesting problem,” Fyneman said and retreated to the long blackboard behind him. He drew a chalk line from left to right and turned to smile at us, “That is the mirror,” he said. Then somewhere in the middle of the board, he drew a little crude spaceship, a beam of light exiting from it and the reflection coming back.

Then he calculated for a few minutes and presented the results of his calculation, an equation for what the angle would be as a function of how fast the spaceship was moving.

“Very good, young man, you are right. You can tell how fast you are going. Special Relativity is wrong.”

There was a stunned silence. How could this possibly be? Special Relativity was a fundamental cornerstone of physics. It had been around for almost sixty years. Validated by scores if not hundreds of independent experiments by the greatest minds in the world. How could an undergrad, a freshman no less, come up with a thought experiment that crashed everything down?

For a few moments, no one dared speak. Then Fyneman cocked his head to the side and returned to the board. He corrected one of his intermediate equations, fixed up the results and turned back to address us. I made a simple error. The angle is independent of the spacecraft’s speed. Special Relativity is saved.”

Everyone laughed at what had just transpired. Of course, no freshman was going to bring all of physics crashing down. If I or anyone else in the room had come up with the formula for what the lag angle would be, we would have checked our work probably a dozen times before making any pronouncements to a room filled with other (aspiring) physicists.

On further thought, what had happened was pure Richard Fyneman. The utter unlikelihood of a freshman coming up with something that would completely upset all of physics must have never entered his mind. Instinctively, he just followed where the equations were leading him. And to me, that was an example of what it took to make true breakthroughs, to be a Nobel Prize winner – ignore the shackles that constrain our thinking onto paths that have been traveled many times before. Who knows what wondrous thoughts might then result.

September 28, 2016

Time Travel and Eclipses

Caution! Before reading further, please review the definition of ‘tongue in cheek’.

Time travel is a staple of science fiction, and with good reason. The paradoxes are delicious to contemplate.

And somewhat related, already there is quite a lot of interest building about the total eclipse of the sun that is due to be visible over a wide swath of the United States on August 21, 2017. I will be in Oregon and already have my fingers crossed that there will be no clouds.

Time Travel

Is such a thing possible? The answer depends on which way you are going—forward or back.

If you go forward, yes, time travel is possible. According to special relativity, we observe the clocks of someone moving relative to us as running more slowly. This fact leads to what is called the twin paradox. One brother blasts off into space while the other remains behind. Each sees the clock of the other running slower. After, say, may years, the spacefarer returns to visit his earth-borne sibling. So, which is now the younger?

It is the traveler who is younger. Among other places, the reason is explained here. In the reference, the stay-at-home twin ages twenty years while the traveler ages sixteen. Effectively the traveler has traveled four years into the future.

Going backwards presents paradoxes too. The classic is to figure out what happens when someone goes back in time and kills his own father before he is born. Physicists say that backwards time travel clearly is impossible. It allows things like the death of a father to happen before they can be caused—by among other things the birth of the murderer. A more folksy argument is ‘If backward time travel is possible, then how come we don’t meet any of the travelers?’

Well, think about it for a moment. Maybe, just maybe, an effect does not always have a cause occurring first and we just have not figured this out yet. And backwards time travelers certainly would be briefed not to do anything stupid. If they were really careful, everything would be OK.

But being careful can be a hard thing to do. Consider fashion, for example. It is changing all the time. Even with the internet, keeping track of the coming and going of fads is not easy. And maybe the time travel machines are not very precise. One might want to visit the sixties but arrive in the twenties instead. As soon as the traveler stepped outside of his machine, he would be immediately spotted as being very much out of place.

For women time travels this is indeed a problem, but for men there is a work around—tuxedos. Yes, men’s fashion does change too, but much more slowly than it does for women. A tux from the twenties might well pass in the sixties with little or no comment.

This means that if you indeed are looking for evidence of time travelers, going to the opera or Nobel Prize ceremonies would be a good thing to do.

Eclipses

There can be other visitors among us as well. Consider the phenomenon of a solar eclipse.

First of all, for such a tiny planet as our Earth, our moon is relatively enormous. From anywhere on the surface, it is one of the two biggest sights in the solar system. That alone is worth the visit of alien tourists.

But the fanstasic thing is that, in addition, the moon is precisely the right distance away from the sun so that a total eclipse can occur. No mere transit across the blazing solar disk, no overlap that is wasted. The moon is blocks out all of the sunlight except for a tiny ring around the edge.

This has got to be an astronomical rarity. What are the odds of such a thing happening? There very well may be no other instance in our entire galaxy. Visiting the Earth during a solar eclipse has got to be on the alien top ten list of things to do.

So, If you have a change to be in the path of totally, please follow up on it. You might see the best of all. There right before your eyes, dressed in a tuxedo, a time traveling alien.

September 14, 2016

Skylark Three

What? You say. You’re not going to devote any attention to an out-of-date, poorly written, politically incorrect novel, are you? The protagonist even commits genocide!

Well, yes I am – with a focus on what it has meant to me rather than its flaws. You can find out what others think of the book by looking at the reviews in Goodreads.

First, some background on the story. What you will read here is not even slightly accurate, even more over the top than the original, but it is the way that I choose to remember things.

Skylark Three is the second volume in the Skylark trilogy by E.E. ‘Doc’ Smith, first published in 1930. It features as the hero, Richard Seaton, earth’s most intelligent man — and fastest draw. The villlian of the series, Blackie Duquesne, is as fast as Seaton with his right, but a shade slower with his left, and that made all the difference.

Seaton, being earth’s most intelligent man, uses 1920’s technology to build the Skylark, a spaceship in which he zooms all about the galaxy. In Skylark Three, he discovers the bad news. The Fenachrone are coming! These guys are so evil they even blow up entire planets just for target practice.

Being earth’s most intelligent man, Seaton realizes that our technology infrastructure of the 1920’s is not sophisticated enough to produce a weapon to stop the Fenachrone. So, for roughly the first two-thirds of the novel, as I hazily recall, he visits planet after planet, searching for the advanced technology base that he needs.

Finally, he arrives at what looks like a promising one. The inhabitants are ecstatic. Richard Seaton has come to save them! They give him a lab to work in. Early in the morning of the first day everyone watches on TV Seaton enter the lab to start.

They stay glued to their sets the entire day, seeing the exterior of the lab and nothing on the inside. Finally, around 5PM, Seaton emerges. The entire planet goes wild in celebration. They knew that Seaton was good, but to build the weapon to defeat the Fenacrone in only a single day — unbelievable!

The reporters swam him. “What is the weapon?” they ask? “A brain liquefier?” “A transmorgrifier?” “An incredible shrinking ray?”

“It has only been one day,” Seaton says. “I don’t have the answer yet.”

“What, are you crazy?” “What are you doing out here?” “The Fenachrone are coming! The Fenachrone are coming! They blow up entire planets for target practice!” “You should be back in the lab working harder. What are you doing out here?”

“Well, first of all I am going to relax with a few cocktails while my wife serenades me with a violin concerto or two. She is quite accomplished, you know. Then, a quiet dinner with her, and after that, off to bed for a good night’s sleep. I will be back in the lab the first thing tomorrow morning.”

“But the Fenacrone are coming!”

Seaton paused for a second. “You just have to pace yourself,” he said.

[Spoiler alert] Surprisingly (?) Seaton does come up with a weapon and almost single-handedly blasts into atoms every last Fenacrone, man, woman, and child.

Anyway, that is how I choose to remember the book. I don’t dare reread it because I know I will be disappointed.

###

So what does this book mean to me personally? Well, for thirty years I worked at an aerospace company, helping to build data processing software for some of our national assets. These systems were one-of-a-kind, doing things that had never been done before. As such, there seldom were models to copy. Everything was new from the ground up.

The process started with a Request for Proposal (RFQ) sent out by the government to companies that seemed to be qualified to build a brain liquefier or transmorgrifier, or whatever.

To respond, each competitor assembled a team of engineers whose specialties covered one of the technologies possibly needed for a solution. Nobody had a Richard Seaton on their staff.

Each of the engineers wrote a first draft of what he thought would contribute to a final solution. Everyone’s writings were posted on the wall for everyone else to read. (This was decades ago. Personal computers and networks had not been invented yet).

Then, armed with the knowledge of what others were doing, each engineer wrote a second draft that attempted to make the whole proposal more coherent.

“Oh, I see you are using two-step logon verification in your section on the operating system. I will mention that in my write up of the Operational Concept.”

This process was iterated, gradually improving the proposal document towards the goal of being understandable and making sense. The writing staff shrunk with each cycle; fewer and fewer engineers took over what they now understood from less able ones who had good ideas but could not convey them clearly.

Eventually, the time was up. The proposal had to be in the government’s hands by a deadline or the contractor could be disqualified from even being evaluated at all.

Most of the time, more or less, this process worked. The final submittal was good enough that the contractor, at the least, would not be embarrassed by what he was handing in. And who knew? What was submitted just might be good enough to win. After all, all of the competitors had the same challenge.

On a few occasions, however, the iterations did not work. There were many cycles, of course, but as the deadline approached, somehow, the words became no better integrated than they had been at the start.

On a few (thankfully) such occasions, with only, say, seventy-two, hours left, I had been the last engineer remaining, and the proposal was a complete mess. It would be an embarrassment to submit. And not handing one in at all was not an option. Both of these choices ran the risk of being dropped from the bidder’s list for the next RFP.

Then, with fewer chances to bid, work would eventually dry up. The more qualified engineers would leave for other companies. The less talented ones that remained would be even less able to respond adequately to whatever RFPs did come in.

In my over-active imagination, over a span of a few years a death spiral resulting in complete collapse of the company was a distinct possibility. The weight of the world was on my shoulders. The needle on my stress meter pinned itself on the right, deep into the red.

And in those situations, I recalled Skylark Three.

What I had to do was a mere pimple on the face of the adversity that was handled by Richard Seaton, I realized. He stopped the Fenachrone, for crying out loud. They were the ones that blew up entire planets for target practice!

And how did he do it? Put in an honest full day’s work, have a calming dinner, a good night’s sleep, and start again fresh the next day. If he could save the entire galaxy from the Fenachrone, the guys who blew up entire planets for target practice, then certainly I should be able to handle my petty problem as well.

I did knock off at 5 PM even though there was only three days left, got my sleep and continued to work through what had to be done the next day.

Self-delusion? Sure it was? But remembering about Skylark Three was what got my stress meter back into the green.

August 26, 2016

Novel writing rules – part 3

Previous blogs discussed the two of three books dealing with rules for writing novels. In this one, I talk about the third — The Fantasy Fiction Formula.

As I presented before, the situation is summarized by the famous quote by W. Somerset Maugham –

“There are three rules for writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are.”

Nevertheless, I plunge on.

The Fantasy Fiction Formula (FFF) is written by Deborah Chester, author of over forty novels and a professor at the University of Oklahoma. As might be expected, unlike the first two books discussed here, one does not have to dig a bit to find what is relevant to writing fantasy novels. Indeed, for anyone starting out, I think FFF is required reading.

The scope is encyclopedic, covering the usual topics of story structure, characterization, viewpoint, etc. The material is dense and would take many readings to be absorbed fully. A beginner might well be overwhelmed and perhaps start that first novel on some other day.

One thing in particular that I liked was Chester’s use of examples. Reminiscent of the format for newspaper bridge columns, she first illustrates the incorrect way to accomplish a writing goal and follows it with a much better way from her own writing.

There are rules aplenty in FFF, but unlike Contagious and Save the Cat, they do not serve as chapter titles or section headings. Instead, they appear in the text without fanfare as part of the ongoing exposition. So, my goal here was not one of twisting rules as presented to make them relevant for novel writing, but instead to detect them when they were encountered. It was like a treasure hunt, extracting pithy gems from the surrounding matrix.

What I found is presented below. I make no claim as to its completeness. I am sure that I missed many more ‘rules’ than I discovered. And presenting them without the surrounding context does them no justice at all. The serious fantasy writer should read the book from cover to cover. No, that’s not quite right. The serious fiction writer should read FFF from cover to cover.

The beginning

“Get your protagonist into trouble in the opening sentence.”

Not the first chapter, not the first paragraph, but the opening sentence! Chester does not pull any punches to soften what she has to say.

In the first few paragraphs, “introduce the protagonist, the story goal, and the central story question.”

In the first thirty pages in addition to the above, present:

“A clearly established viewpoint

Setup of story situation

Location and time of day

Introduction of immediate antagonist

Scene action and conflict

Hints for later developments

Small hooks to grab reader curiosity

First complications”

In the first paragraphs! In the first 10,000 words! This strikes me as a pretty tall order, but Chester asserts that it can be done and easily.

Characterization

“For your protagonist, select four or five positive traits…and then mix in a couple of flaws”

Complexity of character “is achieved when a character’s inner problem or flaw is in conflict with that character’s external situation or behavior.”

“True nature is revealed by what a character does under stress”

“George R.R. Martin’s popularity notwithstanding, its best if you avoid tacking an ensemble cast of multiple protagonists until you’re an extremely skilled and experienced writer.”

Scenes

Chester has an interesting take on the basic elements of a novel — narration, scenes, and what she calls sequels. She devotes several chapters to discussing scenes and sequels, and I found them to be the most instructive part of FFF.

Scenes are “confrontations between at least two characters in disagreement over a specific objective.”

“Every scene. . . is designed to remove the protagonist’s options, one by one, until the protagonist has no choice but to face the villain in the story’s climax.”

“Following a scene,…it is necessary to give your readers a breather. You do this by allowing your protagonist some processing time, plus a chance to react to whatever hurtful things have been said or done to him.”

“Dialog advances plot by stating the scene goal.”

“Never shift viewpoint within a scene.”

The middle

“…you can’t set up a novel with only one, super-huge, overwhelming plot question…and nothing else…You need more than that because no matter how clever or intriguing it is, if that’s all there is, readers will grow tired of it.”

The ending

“[The] protagonist is cornered and faced with a moral dilemma. All the options are poor but the protagonist must choose one and act on it according to his or her true nature”

Glossary

“Don’t even think of adding a glossary at the end of your manuscript. You are not Mr. Tolkien and do not rate his privileges.”

Now, I learn this! The second editions of my three books are already going to press. One of my motivations for producing them was so that I could include glossaries. Some readers of Master of the Five Magics complained about the usage of archaic architectural terms in my description of the Iron Fist castle and that detracted from their enjoyment of the novel.

And once I got rolling with glossary entries, I discovered that it was a lot of fun to include expanded material on other little grace notes in the text. Oh, well.

###

As I said, the list above is only the tip of the iceberg, a sampling of ‘rules’ that happened to resonate with me. What gems did you find? I would like to see your comments.

August 12, 2016

Novel writing rules – part 2

My previous blog discussed the first of three books dealing with rules for writing novels. In this one, I talk about the second — Save the Cat.

As I presented before, the situation is summarized by the famous quote by W. Somerset Maugham –

“There are three rules for writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are.”

Nevertheless, I plunge on.

Save the Cat, by Blake Snyder, is a book about writing screenplays. As one might expect, not all of the material there applies to novels — things which have a much broader scope. But I think it is an interesting exercise to examine what is presented through the lens of a novelist.

The first five chapters cover many aspects of screen writing: developing the logline, ten movie genres, characteristics of the movie protagonist, and so on. There is a lot well worth reading there, even for the novelist, but for my purposes here, I will focus on chapter six: The Immutable Laws of Screenplay Physics.

Immutable Laws — is that on topic or what!

I found that some of the immutable laws apply to novel writing and some did not. Here’s the roll call

Save the Cat — applies

“The hero has to do something when we first meet him so that we like him and want him to win”

When I look back at some of the reviews of my first novel, Master of Five Magics, written over thirty years ago, I am struck about some on the comments that said that the hero, Alodar, was driven, competent, etc. but he was also arrogant — not a likeable character.

Now I never had Alodar kick old ladies out of the way or stomp on babies, but there it was — arrogant. Who knew?

Shortly after finishing my read of Save the Cat, (within hours) my wife and I saw the movie “Me Before You”. In the very first scene, the male protagonist is hurrying off to work, and as he crosses the street is hit by a car and becomes a paraplegic. But in a single line tossed off to his wife as he had left the apartment had been something like, “I will take care of dinner tonight”.

Wow, I marveled. He had saved the cat!

In the second scene, the female protagonist who would eventually become the caregiver for the injured man tells two women standing before her counter at a bakery something like, “They have fewer calories if you eat them standing up.” The customer guilt is swept away. She too had saved the cat!

Thereafter, I paid much closer attention to the structure of the movie than I had ever done before, and was agog at how much advice of the book had been followed in the screenplay. The movie was written by the author of the novel, which is unusual I guess, but either Jojo Moyes was also a reader of the book or she has incredible screen writing instincts.

So why not go ahead and save the cat in a single protagonist centered novel? It only takes one line or so, and if no big deal is made of it, it should only help.

Now, before reading Save the Cat, I had already finished my revisions to the second edition of Master of the Five Magics, and it was cast in concrete for the production process. I hurriedly reread what I had written in the new Chapter Two, and to my relief, coincidentally there happened to be a line or two that might qualify as following the rule.

Yes, cat saving is definitely something to be aware of when writing a novel.

The Pope in the Pool — applies — but how does one do it for a novel?

Bury the “backstory or details of the plot that must be told to the audience in order for them to understand what happens next.”

Well, OK. No argument on the validity of this one. But how does one do this? How does one bury essential information so that it does not get in the way?

The book does go further than just stating the rule. It presents a technique that works for movies — have some interesting visual going on for the viewers to watch while the explanatory words are happening as a voice-over — like the pope taking a swim in the Vatican City swimming pool.

Double Mumbo Jumbo — doesn’t apply

“Audiences will accept only one piece of magic per movie”

This is a rough one to follow in a fantasy novel, although it probably has merit for a more general audience. What Snyder is saying is something like – “Magic, OK. but magic and aliens, and time travel and …” is definitely not OK.

Laying Pipe — applies

“Audiences can stand only so much pipe”

Snyder defines pipe as all of the initial setting structure that is necessary in order for the story to get off the ground.

My reaction to this was, “of course, but in so doing one is creating downstream problems that in movies are solved by Popes in the Pools. Not so easy to follow in an novel.

Too Much Marzipan — maybe applies

I suppose that all of us writers aspire to be more than just formula hacks — churning out prose that does not have literary value. So we introduce little tidbits along the way and they all tie together in the final satisfying reveal of what is actually going on.

Perhaps having something like:

The nursemaid who vanishes when the castle is stormed and Destiny’s Darling is kidnapped. – Turns out she secretly was his aunt and gave him a crucial power needed in the climax.

The sword that could never be drawn except in uncontrollable rage? – It was forged from no less than steel taken from the ruins of the castle.

The feather he wore in his cap? From his guardian wren who had sang at the protagonist’s cradle side

that are all crucially needed for the hero to defeat the dragon in the end.

Snyder says, “You cannot digest too much information or pile on more to make it better.”

Clearly, I was guilty of this in Master of the Five Magics. My editor, Lester del Rey, in analyzing the first draft of Master of the Five Magics said something along the lines of

“OK, you have set up five types of magic in detail and have Alodar move from one to the next. But why? What is the purpose of all of that?”

So for my second draft, I wove back in the threat of demons and what the wizards had prepared as a defense. It answered del Rey’s question, but at the expense of a huge long exposition at the end of the book, violating Snyder’s rule. I knda liked what I did, but perhaps it was too much marzipan.

What would I do differently now? I do not know. Even after reading Save the Cat, I don’t know.

Watch out for that Glacier – applies

Snyder says that the danger to the protagonist always has to be imminent. Gradually getting closer just does not hack it. Heros need challenges right here and now. Sure, the aliens are going to be here in a decade or so, but right now, he has to deal with the boa constrictor that is swallowing him. If he is in a movie for which the danger is not immediate, Snyder’s instinct is to yell out in the theatre, “Watch out for that glacier!”

The Covenant of the Art – applies – but, gosh, everybody

“Every single character in your movie must change in the course of your story”

Well, sure the protagonist must change. However, except for the bad guys who remain bad, Snyder says that everyone else must change. That’s a tall order.

Keep the Press Out – does not apply

Do not have exposition or advances in the plot occur though the actions of the media.

Summing up

These brief paragraphs do not do Snyder’s book justice. It is a very enjoyable read. Totally unacademic in tone, breezy, funny, and chocked full of examples. While I was reading it, I found myself repeatedly thinking, “That’s why I enjoyed that movie so much,” or “That’s why I did not.”

A treasure trove of advice for the novelist as well as the screenwriter. Highly recommended.

Next time I will be finishing this series by discussing The Fantasy Fiction Formula by Deborah Chester

July 22, 2016

Novel writing rules – part 1

Many how-to books have been written on novel writing, and most aspiring writers probably has sampled many of them. But as we all know, although they can provide guidance, no set of hard and fast rules exists. If they did, computers would write everything and we all would be out of a job.

The situation is summarized by the famous quote from W. Somerset Maugham –

“There are three rules for writing a novel. Unfortunately, no one knows what they are.”

Nevertheless, guidelines and so-called rules are good to know about. At the very least, provide a checklist one can check their writing against to see if some additional tweaks can change something that might be good into something that is great. In that spirit, this blog and the two following will discuss three books

Contagious by Jonah Berger

Save the Cat by Blake Snyder,

and

The Fantasy Fiction Formula by Deborah Chester

The first two are not how-to books for writing a novel, but I have found it helpful to look at them through the lens of an author rather than that of the intended audiences.

###

Contagious –Why Things Catch On, is an exploration of what causes certain products, ideas, and behaviors to be talked about more than others. Jonah Berger is a marketing professor at the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. I found the book to be quite informative and entertaining. It is filled with examples from real life and backed up by quantitative research.

As Berger explains, things go viral because of word of mouth (well, duh!). But quite surprisingly, only 7 percent of word-of-mouth occurs on-line. Most of it happens in face-to-face conversation. From his research, Berger concludes that something going viral possesses one or more of six important characteristics of contagiousness:

Social currency: — makes us seem more interesting to others.

Triggers: — is connected to things in our environment that recur repeatedly

Emotion: — creates an emotional response

Public:– is visible to others

Practical value:– is useful

Stories: — is communicated by telling a story

Of course, to understand the details of what each of these labels really means, you would have to read the book. It was published in 2013. But for a more recent simple example of why someone engages in word of mouth, consider the explosion of interest in Pokémon Go by almost everyone. A person talks about Pokémon Go because:

He can tell others how many Pokémon he has captured and where he found them. He shows he is playing the game well. — Social currency

Every time he picks up his cellphone, he is reminded of the game — Triggers

He has a feeling of nostalgia about when he was much younger when he plays the game. — Emotion

He sees all these other people walking around that are also staring at their phones – Public

He feels good that he is exercising. After all, exercise is a good thing – Practical value

He can tell others what happened last night when hundreds people converged on the bagel shop. — Stories

###

OK, Contagious is an interesting read. However, what does it have to do with writing?

Well, think about it. Books are products marketed and sold primarily by word of mouth. So, the question arises — what can an author do to give a novel one or more of the six characteristics that increase its chances of going viral?

The following is the result of a mental exercise of trying to apply what I learned from Contagious to writing fantasy novels. As you will see, nothing I came up with is earth shaking; all are just little tweaks. I did not discover one of the three unknown rules of novel writing.

But the exercise of looking at things through the lens of a writer seems to me to be a good thing to do.

Social currency

Berger discusses three subcategories in Contagion: sharing a secret, relating performance in playing a game, and passing on something remarkable.

Maybe someone else can see how to incorporate one of the first two concepts into the act of writing, but I didn’t. The third, however, presents possibilities.

Berger gives the example: “A ball of glass bounces higher than a ball of rubber” – a fact to relate to a friend. As authors, we probably all have a store of such trivia stashed away in our heads. When I read about bouncing balls, one immediately came to mind from over five decades ago. It was “Mouse milk costs over $300 an ounce.”

Thanks to the Internet, I was immediately able to verify this and learned that mouse milk did cost over $300 an ounce, but that was in 1947. Now it is down to $1 an ounce – probably due, I am guessing, to the improvement in mouse milking machines.

Now, it probably is a challenge to work mouse milk into a fantasy and make clear to the reader that the cost being talked about is for our own world, but I think the basic idea is a good one to keep in mind. In sword and sorcery, for example, there is a lot of medieval weapon vocabulary that might be of interest to a reader and something to chat about with a friend. In my first book, Master of the Five Magics, I used a lot of words dealing with the architecture of castles. After all, literature elucidates as well as entertains.

Triggers

Marketing lore for writers tells us that a part of a well-orchestrated campaign prior to the publication date is to get many on-line reviews. There are many websites that talk about how to find on-line reviewers, politely ask them if they are interested in reviewing your book, and (under the radar) get agreement to trade reviews.

One piece of advice that struck me about review solicitation, however, was a discussion of the mental attitude of the reviewer. Does one really want someone to comment on what you have done, not because he freely choose to do so? Would not he feel an obligation to make the review a little more negative so it is “well-balanced”?

Yes, yes, even negative reviews are worthwhile. Berger comments that for new or relatively unknown authors, negative reviews increased sales by 45%. But, one of the key points of Berger’s chapter on triggers, however, is that the more powerful triggers are recurring ones, not ones that just occurred once and then were done.

That suggested to me that perhaps something to consider is solicitation of reviews all right, but not to bust a gut for a new book’s rollout. Instead, after the book has been out there and, presumably, got some good reviews at the outset, then periodically and continually start asking for more. If bad reviews are good for sales anyway, then a steady stream of them perhaps could help one’s book ‘break out’ and go viral. The repetition of reminders is the key.

Emotion

Of course, all writers hope that what they have written is good enough that a deep emotional response is generated in the reader. From the standpoint of going viral, however, the results of Berger’s research concluded that not all emotions are equally effective in generating word of mouth referrals.

He lists the ones more likely to contribute to virality are: awe, excitement, amusement, anger, and anxiety. Ones least likely are contentment and sadness.

Interesting. Action/adventure novels do strive to create excitement and anxiety. Humorous novels are fun to read (and hard to write). But awe? It ranks right up there in the experimental results, and I had never considered it in the context of fantasy.

How does one create awe in a fantasy? I don’t know. But perhaps this is what in science fiction refers to as “a sense of wonder”. If so,Berger is saying fantasy should strive to create the same feelings as well.

And sadness is not so powerful? A well-written tragedy might well generate a deep feeling of sympathetic grief in the reader. But from the standpoint of word of mouth, sadness is not a strong characteristic. Evidently, few people want to be identified as a communicator of downers.

Public

For books, this is a hard one. Book reading, by in large, is a solitary activity. You might just eat up a L. Ron Hubbard decalogy, but no one watches you doing it.

So I did not come up with something for this characteristic. Well, as Berger says, not all six are necessary.

Practical value

There are possibilities here. Yes, as authors we want to write great stories – great escapes in which the real world is left behind. But inserted into the stories can be mini-stories — tips that can apply in real life as well as fantasy. These do not have to be long elaborate things that drive the plot, but such things as, well maybe — how to distract someone’s attention away from a doorway…

Buy a strip of caps for a cap gun (do they still make these things?) and some air riffle bbs. Wrap a cap around a bb and place them in the middle of a small square of tissue that is about 1 inch on a side. Gather the four corners of the square together and twist until the bb and cap are firmly secured to one another. Smooth out the tissue above the twist into a flowing tail. Make a handfull more of these the same way.

Then when the collection is tossed into the air near the target, the light tissue tails and heavy bbs will force the caps to hit the ground first. There will be a pop-poppa-poppa-pop sound, and the target will turn to investigate what is causing the noise. While he is distracted, you can now rush through the door. Remember, you heard it here first.

Stories

Well, of course, the novel itself is a story. One does not want the whole thing given away when one reader is talking to another. But how about something like the backstory of one unusual character — not critical to what transpires, but something that is interesting to talk about.

OK, exercise over. For me, it was a fun thing to try. Six more things to think about when writing the next novel.

Next time, I will be discussing Save the Cat.

July 7, 2016

Tweak and try again

I am a Goodreads newbie and am still in the process of digesting all of the material that is available on the website. One thing that I have found is that many authors report on their results from trying things like giveaways or other promotional ideas. This is good info, and I am glad learn about what has happened in the real world. I have noticed, however, that some reports include comments along the lines of “It was a failure; I will never do that again.”

Of course, there is no magic bullet that guarantees a wide readership, and time is an author’s most precious commodity, but it occurs to me that something from my own experience might be relevant here.

Now, I want to very clear. I am not using this post so that I can brag about things. The actual details are entirely irrelevant. It is an observation about what happened that I want to talk about.

I did my writing over forty years ago, in the infancy of computers and just the beginning of the internet. Back then, one typed a manuscript, put it into the box that a ream of typing paper came in, crossed one’s fingers, and physically mailed it off to a publisher in New York with return postage enclosed. About three months later the box would return with a rejection letter, and one would send it to the next publisher in line.

I had written a fantasy and in the 1970’s had just four targets, the first of which was Ballantine Books, now a subsidiary of Penguin-Random House. Sure enough, it came back, and I followed the established routine. A year later, I had my manuscript back for the last time, and nowhere else to go. I was not going to be a published author.

Some time passed. I don’t remember how long, when I learned that Lester del Rey, the science fiction author had been hired by Ballantine to be their new fantasy editor.

On a whim, I decided to submit my manuscript to Ballantine again. No changes in the text. No change in the cover letter. No mention that I had tried with them before. Sent to the same address. I may have added “Attn: Lester del Rey” to the address label but this many years later I am not sure.

Son of a gun, I got an acceptance letter back from del Rey. I was going to be a published author after all.

The point is that circumstances change. They did so in the 1970s. In our computer-enabled age, they certainly do so now. So it just might be worthwhile to try something again – but perhaps with a little tweak like ‘Attn: Lester del Rey’—that can make a world of difference.

Another example is one related by another science fiction author, Friedrich Pohl. At one point in his career, he was working for a publisher whose business model was to use the US mail to send out solicitations to purchase books. Yes, crazy things like that happened back then.

Anyway, there was a coffee table book – something like ‘Birds of America’ – that just would not sell. Pohl used all sorts of enticements but none worked. Finally, in desperation he tried “Do you need a big book?” This worked and the book inventory started to fall.

The moral of the story is that giving up after one try might not be the only option to consider. Perhaps trying again with some tweak could produce better results. You have already gone through all of the steps once. The second time around will take a lot less effort. Obvious candidates are things like the blurb for a giveaway, or the text in the email asking a blog reviewer to look at your book, or …

Keep track of the results for each try to see if you are on the right track. Who knows, maybe success is just a little tweak away.

Just a thought.

June 21, 2016

How many guppies?

From Marilyn Vos Savant’s column in Parade Magazine, June 19, 2016

Say you have 200 fish in an aquarium, and 99 percent of them are guppies. You want to reduce the proportion of guppies to exactly 98 percent. How many should you remove?

— M.S., Winston-Salem, North Carolina

Give it a try. The answer is surprising.

In this tank of fish, 198 are guppies. If you remove two, they will still constitute almost 99 percent of the fish (196 guppies in a tank of 198 fish equals 98.9898… percent). Even removing 20 guppies won’t help much more. Their proportion will still be 98.8888… percent. You would need to remove 100 guppies to drop their proportion to 98 percent (98 guppies in a tank of 100 fish).

June 17, 2016

The joy of kite flying

As a youth, I found a special joy in flying kites. Not in just getting one up into the air but in seeing how high and far away they could become. Somehow, there was a special serenity in leaning back against a tree while a breeze was blowing and doing nothing but watching my sentinel in the sky.

Nowadays one can spend a serious amount of money buying fancy kites of various designs. Some are made of plastic and others of cloth. Some have fancy non-aerodynamic shapes but boldly display superheroes or cute little animals.

In my day, kites were purchased from the local dime store. They came in two types: diamond or box. The diamond kit cost ten cents, or maybe it was fifteen, and the box kite considerably more.

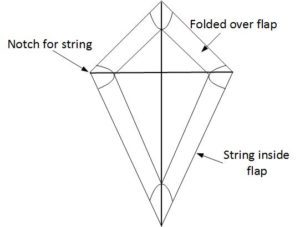

The diamond, or Malay, kite consisted of two sticks of balsa wood, one about two thirds as long as the other and bound together by a single loosely fitting metal band. You rotated one of the sticks until they were at right angles to one another, forming a simple cross.

The sticks were packaged rolled up in a very light paper shaped like two triangles placed together base to base. A small strip of each outer edge was folded and pasted over a loop of string that ran around the circumference. The string was visible at each of the four corners of the kite.

Both of the sticks had notches in each end, and the four exposed portions of the string loops were inserted into them. If one pierced a small hole in the paper covering near where the two sticks crossed and tied a kite string around the vertical one, the kite was reputed “ready to fly.”

Well not quite. Although the diamond kite was touted as a tailless kite as originally assembled , in my experience, it was a very poor flyer.

Many of the small plastic kites available today have the same characteristics. If the wind is too light, then it is impossible to get the kite high enough by running to escape the turbulent air near the ground caused by nearby buildings and trees. If the wind is too strong, the kite’s inherent instability causes it careen around and eventually crash breaking the sticks or ripping the plastic or whatever. There is a sweet spot when the wind velocity is just right and the kite will fly, but it is extremely narrow.

From time to time I wonder how many times a parent has taken a young child to a city park planning to introduce them to the joy of seeing their possession defying gravity and soaring into the sky only to give up in frustration after a few dozen failed attempts.

Yes, the wind has to be strong enough that the weight of the kite can become airborne. But more than that, the kite must be stable in all three directions of motion – pitching up and down, yawing from left to right, and rolling from side to side.

If properly rigged and the wind is strong enough, however, a simple diamond kite can be launched by simply holding it front of you with your back to the wind, gently releasing it and letting it rise.

Yaw

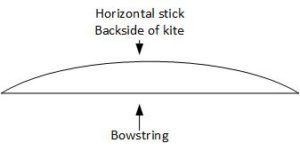

The first thing to do is attach an additional string on the backside of the kite running from one end of the horizontal stick to the other. The length of the string is shorter than the stick itself so that the it becomes bowed in a gentle arc.

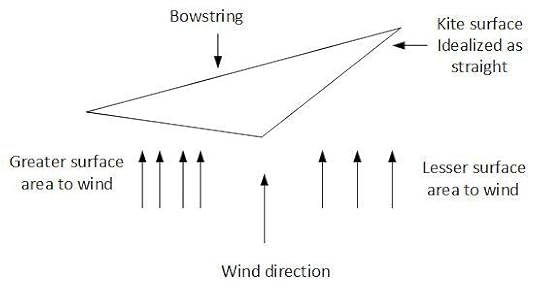

Now, when the wind is blowing on the kite, what is called a dihedral angle is produced. A single flat surface is not presented to the wind but two slanted ones. If, because of a swirl of the air, the side of the kite on the left of the vertical stick is pushed away from you, it presents less surface to the wind. At the same time, the rotation causes the right hand side to present more.

Then there is greater wind pressure on the right side than on the left, and the kite rotates back to a position in which the forces are balanced. This is a perfect example of what engineers call “negative feedback” — a system automatically correcting itself when things get out of whack.

The more you bow the kite, of course, the more stable it becomes against yawing to the right or left. However, at the same time, less and less surface area faces the wind and the ability of the kite to lift diminishes. A modest amount of bowing is all that is needed for most kites.

Bowing a kite is no secret. Although the diamond kite is reputed to be of Malaysian origin, the Japanese were bowing their kites for centuries as well.

Pitch

The second thing to do is to disregard any instruction to attach the kite string to the kite at only a single point. If a gust of wind hits the larger triangle of the kite below the point of attachment, there is nothing to stop it from continuing to rise until the entire kite presents very little surface to the wind, and it starts plummeting to the ground. Another gust catches it as it falls and crazy things begin to happen.

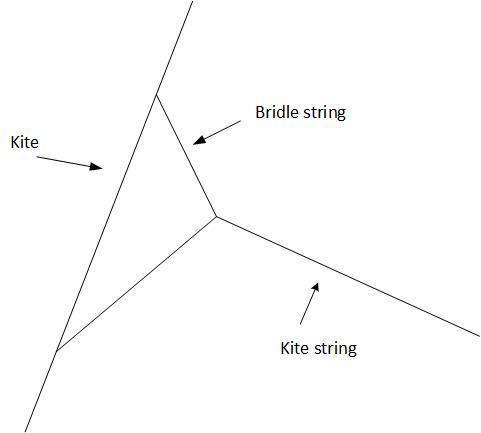

Two points of attachment should be used and not just one. Attach a short piece of string to the vertical stick about half way between the horizontal one and the top of the kite. Attach the other end halfway between the horizontal stick and the bottom. Finally attach the kite string itself to this new one producing a triangle when the wind blows.

This bridle, as it is called, also creates a negative feedback. If a gust blows on the bottom half of the kite, the tension in the lower portion of the string becomes greater than the upper and the kite is righted.

Bridle strings too are no secret. The only tricky part is adjusting the point where the kite string is attached to the triangle so that the angle the kite makes in the wind is a good one. Attach too high and the kite flies to horizontally and has little lift. Attach too low and it has too little lift as well.

Roll

This one is the killer. Kites sold in stores nowadays have a few little ribbons of plastic streamer hanging at the bottom that serve no useful function at all. The purpose of a tail is to stop the kite from rolling. In my day, the conventional wisdom was that it was the weight of the tail that prevented a kite from starting to pivot from its upright position and start to rotate about the kite string. A length of knotted rags, the heavier the better was the thing to use.

The thing is that if you want a kite to soar so high that you can barely see it, adding a lot of weight is not what should be done. The wind is what holds everything loft, the kite, the tail, and the kite string. The less weight devoted to the kite and tail, the more that can be used to lift string.

I don’t remember if I thought of this myself or one of my parents told me what to do. But here is the secret that will you a champion kite flyer in the eyes of your friends.

Get an old bed sheet, one, say, about eight feet across. Starting at one edge begin tearing a half-inch strip of material away from the sheet. However — this is the important part — do not complete the tear. When you get to about an inch from the other side, stop what you are doing and begin another tear about a half inch separated from the first and going in the opposite direction. Do this about six or seven times and complete the final tear all the way across.

Now you have a light tail that is about 50 feet long, but with no useless knots. It will produce sufficient wind resistance to rotational forces that your kite will be stable against rolls.

The Endorphin Rush

On a blustery day, take a properly built diamond kite to an open area. Lay out the tail in a straight line on the ground. Put your back to the wind and slowly let your kite leave your hand. Watch it majestically rise into the air with no twitching, no bobbing, and no rotation — a stern monarch of the sky. Let all of your string out until it can barely be seen. Get a comfortable place to sit and marvel at what you have done.

PS

In the modern age, there are restrictions against flying kites weighting more than five pounds above 500 feet. Near airports, this applies regardless of weight.