Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 93

April 2, 2023

Morandi or bore-andi

CALL ME A PHILISTINE if you wish but I was underwhelmed by the much-hyped temporary exhibition of the works of the Italian artist Giorgio Morandi (1890-1964), which is being shown until the 28th of May 2023 at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art in London’s Canonbury district. Morandi, who was born in Bologna (Italy), where he lived most of his life and died, was primarily a still-life and landscape artist. Without doubt, his works are both carefully and extremely well executed. However, his numerous still life works depicting bottles, jars, and other containers, did little to excite my interest in them. His landscape images appealed to me more, but not much more. For me, almost the best work in the show is a self-portrait, showing Morandi seated.

Compared with the other works in the Estorick’s permanent collection (e.g., Balla, De Chirico, Modigliani, Boccioni, Music, Greco, Manzu, and Russolo), all of which are highly creative and visually exciting, poor old Morandi’s work pales into insignificance. Having expressed my opinion about the temporary exhibition, I must admit that many of the other viewers I saw today seemed to find Morandi’s works of great interest. Many of them stood staring intensely at individual works for minutes rather than a few seconds. Few of the works in the exhibition grabbed my attention for more than a few instants.

Well, maybe I missed something that other people see in Morandi’s art, but if someone were to give me a genuine Morandi, I would sell it as quickly as possible, and might spend the money on a work by a more interesting Italian artist.

April 1, 2023

Seeing the world inside out

THE ARTIST RACHEL Whiteread (born in Essex in 1963) sees the world from an original perspective. Her sculptures depict the spaces contained within or around objects. One of her sculptures currently on show in an exhibition in London’s Tate Britain Gallery illustrates her approach well.

The artist has made a plaster cast of the space enclosed by the staircase in the building housing her studio. When you look at the artwork carefully, it can be seen to consist of sections of plaster, rather than one single piece. I am guessing that what Whiteread did was to make plaster casts of parts of the staircase, its walls, and ceiling, and then assembled them to create what is effectively the shape of the space enclosed by them. The result is something that at first glance makes one think of staircases, but after a few moments realisation, you notice that it is not what it first seemed to be.

One of the artist’s first and maybe best known works was created in October 1993. Called “House”, it was a plaster cast of the interior of a whole house, which was about to be demolished, on Grove Road in the East End of London. I remember going to see this unusual artwork during the short time it existed; it was tragically demolished by the local council in January 1994.

In addition to large projects such as described above, Whiteread has created many smaller works, such as plaster casts of the insides of containers (e.g., hot water bottles) and the spaces surrounding objects (e.g., chairs and doors). However, it is the larger works like the staircase and the house that I prefer.

Some people may criticise Whiteread’s work as being, to quote Hans Christian Andersen, the stuff of “Emperor without clothes”, but that is a simplistic view of her creations. What artists like Whiteread (and other much criticised artists such as Picasso) make us do, is to see and consider things in a new way – you might say “with new eyes”.

March 31, 2023

Imperfect symmetry

St James Park, London

St James Park, London What is it that attracts us to reflections in stretches of water such as lakes, rivers, and ponds?

When the water surface is completely still, the reflection is almost, if not completely, perfect. This is fascinating but not as exciting as when the water surface is not smooth. In this case, the reflection is not perfect; it is usually distorted in an interesting way. And because the water is not still, the reflection changes constantly, making it more interesting than when the water surface is smooth and mirror-like.

Why is it that I like these imperfect reflections? I wish I could tell you.

March 30, 2023

Art of heros

GEORGE FREDERIC WATTS (1807-1904) was a prolific, highly acclaimed Victorian artist. Visitors to London’s Kensington Gardens can easily admire one of his works, a sculpture called “Physical Energy”. Standing across the Serpentine from a sculpture by Henry Moore, Watts’s sculpture is a bronze casting of a version of it that was sent to South Africa as part of a memorial to Cecil Rhodes. One of Watts’s less prominent works, and quite a curious one, can be seen in Postman’s Park, which is a few yards north of St Pauls Cathedral in the City of London. It is the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice.

The memorial consists of a wall covered with rectangular plaques, made with ceramic tiles commemorating heroic deeds carried out by ordinary people. For example, one bears the words:

“Frederick Alfred Croft. Inspector aged 31. Saved a lunatic woman from suicide at Woolwich Arsenal Station but was himself run over by a train. Jan 11, 1878”.

And many other examples of great bravery by civilians are recorded on the wall, which is protected by a canopy with a decorative fringe.

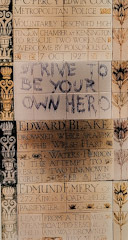

By Susan Hiller

By Susan HillerThe artist Susan Hiller (1940-2019) was born in Florida (USA) and died in London. Apparently, she was surprised by how few people noticed the memorial in Postman’s Park, let alone read the tragic plaques. I am one of the few, who have done so. So, as soon as I got near to an artwork displayed in a temporary exhibition in the Tate Britain art gallery, I knew it was based on the plaques in Postman’s Park. The piece consists of 41 photographs of plaques on the Memorial, which have been arranged on a wall by Susan Hiller. In the centre of this artistic array that she has called “Monument 1980-1”, she has placed a plaque which consists of a stretch of tiling on which the words “Strive to be your own hero” have been crudely written with black paint.

Susan Hiller’s interesting version of GF Watts’s Memorial is one of several intriguing exhibits in an exhibition called “Material as Message”, which was still being installed when we visited it in March 2023. There is yet one more exhibit to be unveiled. Hiller’s exhibit interested me because I am familiar with Postman’s Park, but the other exhibits were equally fascinating both visually and conceptually.

March 29, 2023

His last mural

THE SERPENTINE NORTH art gallery is housed in what was once a gunpowder store, built in 1805. Next to it, there is an elegantly curvaceous café created by the Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid (1950-2016). Until the 3rd of September 2023, there is an interesting exhibit behind the north side of the café. It is an abstract mural of brightly coloured, differently sized rectangles and squares. When I showed a photograph of this to our daughter, she said it reminded her of African printed textiles. Maybe, this should not be surprising suggestions because the mural was painted by a Ghanaian artist, Atta Kwami (1956-2021), who was born in Accra.

The mural, painted on wood, is titled “Dzidzɔ kple amenuveve”, which means ‘Joy and Grace’.

The Serpentine’s website noted:

“Its title is in Ewe, a West African language spoken by Kwami, and its composition characteristically plays with the colour and form improvisations distinctive to Ghanaian architecture and strip-woven textiles found across the African continent, especially kente cloth from the Ewe and Asante people of Ghana.”

Sadly, the mural is the last public work that Atta Kwami created. He died in the UK shortly after he completed it.

March 28, 2023

Knots, threads, and folds

THIS MARCH (2023), we have seen several exhibitions of works of art and craft involving the use of braiding, knotting, weaving, and other methods of employing threads. We saw the exhibition of Kimohimi braiding at the Japan House in Kensington. At the Tate Modern, we saw the quipus created by Chilean Cecilia Vicuña and the wonderful exhibition of imaginative fabric sculptures made by the Polish Magdalena Abakanowicz. Today, the 26th of March, we visited the Serpentine North (formerly ‘Sackler Serpentine’) Gallery in Kensington Gardens. We visit this place often because it usually has exhibitions which are always of interest and frequently pleasing aesthetically. Until the 10th of April 2023, the Serpentine North has a display of sculptures by the African American artist Barbara Chase-Riboud (born 1939 in Philadelphia, USA). We had never heard of her, but that did not surprise us as the gallery often shows works by artists, who are new to us.

A talented child, she entered the Fleischer Art Memorial School in Philadelphia. This establishment, which was opened in 1898, offered free art classes to children. After a successful school career at the Philadelphia High School for Girls between 1948 and 1952, she was awarded Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Tyler School at Temple University in 1956. By 1960, she had moved to Paris (France). Just before that, her eyes were opened-up to non-European art when she made a trip to Egypt.

The beautifully produced exhibition hand-out related that in Paris, she:

“… found herself among a diverse community of socio-politically engaged writers, artists and thinkers including James Baldwin, Alexander Calder, Max Ernst, Dorothea Tanning, Lee Miller,and Man Ray. Moreover, through extensive travelsto Egypt, Turkey and Sudan, she deepened herknowledge and appreciation of global art and architecture, which continued to shape her artistic production from this point onwards.”

The Serpentine exhibition is called “Infinite Folds”. This is a good name because many of Barbara’s works involve the use of folded materials, be they sheets of fabric or of cast metal. In many cases folded sheets of metal are combined with bundles of silk or wool threads, often knotted in places. Some of the metal sculptures appear to have skirts of fabric threads. The artist makes these works seem as if the metal is being supported by the threads – giving, as she said, the impression that the wool has become the stronger material and the folded metal sheets the weaker of the two.

Some of the works are the artist’s interpretations of ancient cultures and traditions of places she has visited such as India and China. Other artworks celebrate famous figures from the past including Josephine Baker, Malcolm X, Nelson Mandela, the Queen of Sheba, and others.

The works in the exhibition are intriguing, well-crafted, and beautiful. They have been placed attractively and well-spaced in the within the old armoury, now the Serpentine North Gallery. When we headed for the exhibition, we had no idea what to expect. What we found was breath-takingly wonderful. Although there is no entry charge, I would have been happy to pay to see this artist’s works.

March 27, 2023

Battersea Park

With layers of roof

Golden Buddhas beneath

A pagoda indeed

March 26, 2023

Getting knotted at the Tate Modern

LONG AGO PEOPLE in the Andes did not write. Instead, as Chilean artist Cecilia Vicuña (born 1948) explained in a note on the Tate Gallery website:

“… they wove meaning into textiles and knotted cords. Five thousand years ago they created the quipu (knot), a poem in space, a way to remember…”

After the Europeans conquered South America, they abolished and burnt the quipus. However, as the artist explained:

“… the quipu did not die, its symbolic dimension and vision of interconnectivity endures in Andean culture today.”

Cecilia has created two large sculptures which are hanging from the tall ceiling of the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall until the 16th of April 2023. Each of these artworks consist of knotted strands of different materials, each of which is 27 metres long. They hang from circular metal structures looking to me rather like shredded laundry. Though they are undoubtedly deeply meaningful and attract the attention of many viewers, I felt the history underlying them was more interesting than their aesthetic qualities.

Abakanowicz

AbakanowiczElsewhere in the Tate Modern, we viewed an exhibition of the works of an artist, who knew how to write, but was creating during a time when the use of words had to chosen carefully to avoid being punished by the government. That artist Magdalena Abakanowicz (1930-2017), was born in Poland, where she created most of her art. After WW2, she studied painting and weaving the Academy of Plastic Arts in Warsaw. Her early works were created during a period when the Soviet-supported Stalinist regime in Poland imposed great restrictions on creative endeavours. During that harsh period, artists had to express any criticisms of the regime in a coded way in order to evade censorship. To some extent, this was necessary until Communist rule ended in Poland. In the mid-1950s, restrictions on art eased up a bit and experimentation became possible.

Magdalena moved from creating flattish conventional woven pieces to innovative three-dimensional artworks – woven sculptures of great originality. Photographs cannot do justice to these amazing creations. Videos can help the viewer appreciate the amazing way that these tapestries both fill and engulf space. However, the best way to see these works is to see them with your own eyes, which you can do at the Tate Modern until the 21st of May 2023. Included in the exhibitions are photographs of the lovely sculptures the artist created in later life and some videos of the artist talking about her work. There is also a film made in 1970 in which her tapestries are displayed on the sandy dunes of Poland’s Baltic coast. The artworks are suspended from poles and move gently in the sea breeze. It is clear from this film, which included scenes showing the fabric sculptures in galleries, that the artist seemed keen to have viewers explore them by touch as well as by vision. Sadly, and probably sensibly, the Tate forbids visitors from touching the lovely artworks.

Both the Vicuña and the Abakanowicz artworks use knotting and weaving to communicate ideas with the viewer. A window in one of the Abakanowicz exhibition rooms overlooks one of the quipu artworks. It intrigued me to see the juxtaposition of the works of the two fabric artists. Seeing these two exhibitions, one immediately after the other, made for a fascinating visit to the Tate Modern.

March 25, 2023

The Brass Rail

I WAS FOURTEEN IN 1966. That year, Selfridges in London’s Oxford Street opened the Brass Rail restaurant on the ground floor, with windows facing Orchard Street. Its speciality was then, and still is, salt beef. I recall visiting the place once or twice with my mother back in the 1960s. In those days, I did not particularly care for the taste of salt beef. For some reason, maybe the cost of the place, we did not frequent the Brass Rail.

Winding the clock forwards several decades, I now enjoy eating salt beef occasionally. Today, the 22nd of March 2023, we needed to go to Selfridges for something, and as we were there, I suggested that we ate at the Brass Rail. Unsurprisingly, the eatery has changed its appearance considerably since the 1960s, but it is still located in the same part of Selfridges as it was originally. Its tables are enclosed in an area lined banquettes upholstered with red fitted cushions. The service was brisk and attentive. We ordered Reuben sandwiches in rye bread. These are generously filled with warm salt beef, sauerkraut, Swiss cheese, gherkin, and Russian dressing.

The Reuben was enjoyable, filling, and quite tasty. However, I felt that the taste of the salt beef was overpowered by that of the dressing and the other ingredients. Good though it is at the Brass Rail, I prefer eating the bagels crammed full of salt beef, which are served at the 24 hour Beigel Bake in Brick Lane. At half the price of the Brass Rail, but without the great service, they are more than twice as enjoyable.

March 24, 2023

The Geometry of Fear

MY MOTHER SETTLED in London in about 1951, a year before I was born. The UK was still recovering from WW2, and life was not too easy. There were shortages of food. I remember my mother telling me that during the early 1950s, relatives in South Africa used to send parcels of food, including, as I can still recall, tinned guavas. The postman used to lug these heavy packages to our home in Hampstead Garden Suburb. My mother used to feel guilty that she was lucky enough to be receiving food that few others could not obtain, and used to open the parcels and give the postman a couple of tins from them. Soon after I was born, my mother, already a painter, began making sculptures. Somehow or other, she managed to get permission to work in the sculpture studios at the St Martin School of Art, which was then located on Tottenham Court Road. She was not enrolled as a student, but worked alongside, and received help from, several sculptors who have now become famous. Amongst these were Antony Caro, Phillip King, William Turnbull, and Elisabeth Frink, who became a family friend.

Most of my mother’s sculpting was done during the 1950s and 1960s. This was a period when many people, including British sculptors, were simultaneously recovering from the horrors of war; fearful of the Cold War and the possibility that it might develop into a war with atomic weapons; and looking towards the future. Sculptors reacted to this situation in various ways as can be seen at an exhibition being held in the Marlborough Gallery in London’s Mayfair until the 22nd of April 2023. Called “Towards a New World: Sculpture in Post-War Britain”, this show to quote the gallery’s press release:

“… emphasises the international impact of a group of young sculptors and artists who merged past trauma, present anxieties, and future hopes into a new visual language.”

Lyn Chadwick

Lyn Chadwick

The artists whose works are on display include, amongst others, Elisabeth Frink, William Turnbull, Reg Butler, Bernard Meadows, Kenneth Armitage, Lyn Chadwick, Graham Sutherland, and Francis Bacon.

Apart from some of the works by Reg Butler and Bernard Meadows, the artworks on display exhibit what the art historian Herbert Read described as:

“…the iconography of despair, or of defiance; and the more innocent the artist, the more effectively he transmits the collective guilt. Here are images of flight, or ragged claws ‘scuttling across the floors of silent seas’, of excoriated flesh, frustrated sex, the geometry of fear.”

The Geometry of Fear was the name of a group of British artists who exhibited at the 1952 Venice Biennale.

Bernard Meadows (1915-2005) was a name that was new to me. He was Henry Moore’s first assistant. Later, he taught Elisabeth Frink at the Royal College of Art. He was a member of the The Geometry of Fear group but as the press release explained he differed from most of its members:

“While the distorted human figure became a prominent motif for many of the artists associated with the ‘geometry of fear’ group, for others, like Bernard Meadows, it was animal imagery that resonated most with the collective societal trauma of the war. Visceral depictions of birds and crabs acted as vehicles to express human emotion.”

I enjoyed seeing this exhibition. The works are well-displayed in the spacious, well-lit rooms of the Marlborough. After viewing the exhibition, I wondered about my mother’s sculptures, most of which now only exist in photographs. Her first sculpture, a terracotta mother and child, was figurative but veering towards the abstract. As time passed, her work became increasingly abstract, and tended to be closer to being brutalist rather than naturalist. Although I never heard her mention The Geometry of Fear, I wonder whether her artistic sympathies lay with them rather than with any other ‘school’ of artistic activity.