Adam Yamey's Blog: YAMEY, page 71

November 8, 2023

His fame as a scientist was eclipsed by Charles Darwin

A SHORT CARRIAGEWAY leads from Piccadilly into the courtyard of London’s Royal Academy of Art. It passes beneath a magnificent tall archway with a curved ceiling. Within the arch there are two doorways leading from the carriageway. The one to the west is the entrance to the headquarters of the Linnaean Society. This organisation was founded in 1788 by Sir James Edward Smith (1759–1828). It is named after the pioneer of modern taxonomy, Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778). It was he who ‘invented’ the modern method of classifying and naming animal and plant species. For example, human beings form the species Homo sapiens. After Linnaeus died, Sir James Smith purchased some of his collections of specimens, books, and other items. These are now preserved by the Society (see www.linnean.org/), which is the world’s oldest surviving organisation dedicated to the study of natural history. Its mission is to understand, disseminate information about, and protect, the natural world.

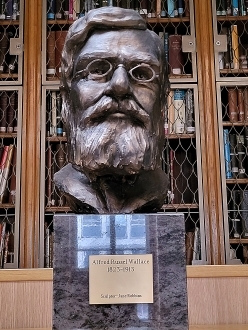

Alfred Wallace in the Linnean Society library

On the first of July 1858, a paper was read to the members of the Linnaean Society. Its title was “On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection”. Its authors were Charles Darwin (1809-1892) and Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913). Both men had come up with the same idea independently – namely, that evolution was based on what is now known as ‘natural selection’. With his publication of “On the origin of species by means of natural selection” in 1859, Charles Darwin eclipsed Wallace as far as being recognised as the ‘father of modern evolutionary theory’. However, the two men continued to be good friends until the end of Darwin’s life. They are both amply celebrated for their achievements by the Linnaean Society.

Apart from making adventurous trips to study species and their variations in the Malay Archipelago – studies that led him to develop his ideas about evolution – Wallace became famous for his other endeavours. His work made him the founder of a discipline known as biogeography – the geographical distribution of species. He was also one of the first people to discuss the deleterious impact of man on the environment. His “Tropical Nature and Other Essays”, published in 1878 warned about the dangers posed by man’s activities (e.g., deforestation). In 1904, he published a work in which he made a serious scientific study of the possibility that there was life on Mars. Wallace’s deep interest in spiritualism, mesmerism, and his views on vaccination (he was against vaccination), led to the downfall of his reputation amongst his contemporaries in the scientific establishment. Sadly, after his death, his name was barely remembered until more recently when several biographies were published. These rehabilitate his reputation as a scientist of great importance.

During our recent visit to the Linnean Society, we viewed a small but fascinating exhibition about Wallace. It is being held in the Society’s magnificent library until the 20th of December 2023. The exhibits include Wallace’s personal library and other exhibits relating to his life and work. Everything is beautifully explained by good labelling, and the library staff were very friendly and informative.

November 7, 2023

A Brazilian artist and the River Ganges at Varanasi

MARINA RHEINGANTZ IS an artist whose works I had never seen until today, the 31st of October 2023. Her exhibition, “Maré”, which means ‘tide’ in Portuguese, is on at the White Cube Gallery in London’s Masons Yard until the 11th of November 2023. Most of the exhibits are painting, but there are also an embroidery and a tapestry.

Marina was born in 1983 at Araraquara in Brazil. She lives and works in São Paulo, Brazil. The works on display at White Cube tend towards being abstract, but they are not completely devoid of naturalistic content. As the gallery’s handout explained:

“Guided by observations of tidal rhythms, ocean beds and meteorological conditions, Rheingantz infuses landscapes of water with a quasi-sentient vitality … Expansive in scale and richly textured, Rheingantz’s landscapes deconstruct topography into its loosest arrangements.”

Although separated from him by many years, Marina’s paintings are almost as atmospheric as the great JMW Turner’s most impressionistic works. However, she has gone further than Turner in her almost abstract depiction of natural phenomena.

For example, this is evident in two paintings (detail from one of them above) she created following a recent visit to Varanasi (‘Benares’) on the Ganges River in India. These depict in an impressionistic way the orange embers that bodies being cremated on the burning ghats spit out onto the surface of the river. Other pictures on display express her perceptions of places as far afield as Brazil, Mexico, and Morrocco.

Not far from Piccadilly and the Royal Academy, White Cube Masons Yard is well worth a visit, It would be a shame to miss viewing the artworks created by Ms Rheingantz.

November 6, 2023

Get a taste of my latest book about travelling in India

Recently, I published a book, “THE HITLER LOCK & OTHER TALES OF INDIA”, which is about some of my experiences of frequent visits to India over a period of thirty years. It consists of an introductory prologue and 101 short pieces of prose. To get some idea about what the book contains, here is one of them.

“IMPROPERLY DRESSED

In August 2008, we spent a few days at a beachside hotel just north of the city of Calicut (Kozhikode) in Kerala. Our accommodation was in the village of Kappad, where it is said that the Portuguese Vasco da Gama might have first set foot on Indian soil in 1498. Whether he did or did not, we had a good holiday in the area despite the occasional monsoon downpours.

One afternoon, while we were being driven through the countryside near Calicut, we spotted an isolated Hindu temple in the middle of a wooded area. It was surrounded by a fence and looked interesting from the car. We stopped, and found an open gate through which we entered the temple compound. The place was deserted – there was not a soul to be seen. Out of respect for Hindu traditions, we removed our footwear before wandering around. I took photographs of what was clearly quite an old temple.

We were on the point of leaving this holy place when we spotted a pandit entering. He walked towards us, not looking too pleased to see us. Speaking in Hindi or English – I cannot remember which – he said that I was not properly dressed to be in his temple. We apologised, and then he asked me to remove my shirt. I did as he requested, hoping that this would improve his mood. After I had taken off my shirt, he asked me to remove my trousers. To be charitable to him, I guess he would rather have had me wearing a lunghi or a dhoti instead of trousers. When he asked me to take off my trousers, we decided to leave the temple compound speedily.

Had I done as he had asked and put on traditional clothing of Kerala, the priest might have felt obliged to make us feel welcome in his temple. But it is likely that he knew full well that a westerner like me was unlikely to do what he wanted, and instead would leave his compound. His actions were a subtle way of getting us to leave without needing to sound impolite or unwelcoming.”

And here is another excerpt:

“DIPLOMATIC AMNESIA

Almost immediately after I first arrived in India (in late December 1993), and a few days before our Hindu wedding ceremony, my father-in-law recommended that I visit his tailor – Mr Krishnan – to get measured up for some new suits. One of these was to be a white ‘Prince Suit’, and the other two were western style formal suits in greyish materials. The Prince Suit, a traditional Indian design with a high neck collar, was to be worn at our wedding reception after the marriage ceremony. The other garments would be useful for the many formal occasions, which my father-in-law anticipated both in India and England. He loved such occasions.

When he worked in an upmarket tailoring shop in Bangalore’s Brigade Road, Mr Krishnan had made suits for my father-in-law. When I met him, he was semi-retired and worked from his home in a small, old-fashioned house on a short lane in a hollow several feet beneath the nearby busy Queen’s Road. He was a short, elderly gentleman – always very dignified and polite. He measured me up for the suits in his front room, which served as part of his workshop. After a couple of visits to try the suits whilst they were still being worked on, I picked up the finished garments. Each of the suits fitted perfectly – ‘precision-fit’ you could say quite truthfully. Despite being so accurately made, they were not in the least bit uncomfortable. Everybody admired them. I could understand why I had been sent to Mr Krishnan.

Our next trip to India was made 20 months later when our recently born daughter had had sufficient vaccinations to allow her to travel safely. During the interval between these two holidays, my dimensions had changed significantly because of my good appetite and happy marriage. Notably, my girth had increased greatly. Sadly, the suits that Mr Krishnan had so carefully crafted no longer fitted me. We returned to see Mr Krishnan, who told us that in anticipation of my dimensions changing, he had left extra cloth within the garments for adjusting them. Without comment, he took my new measurements, and noted them down in a book. My wife, who had accompanied me, said to the tailor, mischievously:

“Just out of curiosity, Mr Krishnan, would you be able to look up Adam’s previous measurements to see how much he has changed.”

He put down his pencil, sighed, and said:

“I am very sorry, Madame, but I have unfortunately lost them.”

Mr Krishnan was not only a wonderful tailor, but also a perfect diplomat.”

If you enjoyed these, and want to read more, then please obtain a copy of my book, which is available in paperback and Kindle from Amazon sites such as

[For those who live in India, the paperback can be ordered here:

https://store.pothi.com/book/adam-yamey-hitler-lock-and-other-tales-india/]

November 5, 2023

An enormous puddle

November 4, 2023

An Albanian conductor and a wonderful orchestral performance

ONCE AGAIN, OLSI QINAMI has conducted the London City Philharmonic Orchestra superbly. Last night (the 28th of October 2023), they performed Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto number 2 and Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring” in the Victorian gothic St James church at the Lancaster Gate end of Sussex Gardens.

Olsi Qinami was born in Albania. At the age of six, he began studying the piano. Then, he studied in Tirana’s Lycée Artistique “Jordan Misja”. Later, he studied at London’s Royal College of Music and also at both the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire and the Ecole Normale de Musique de Paris. A website with his biography (www.olsiqinami.com) noted:

“Olsi continued his studies with Paavo Jarvi at the “Jarvi Conducting Academy”, Riccardo Muti at the “Riccardo Muti Opera Academy” with Orchestra Giovanile Luigi Cherubini, “Orkney Advanced Conducting Course” with Alexander Vedernikov & Charles Peebles and “the Royal Northern College of Music Advanced Conducting Masterclasses” with Mark Heron. He also studied with, Jorma Panula, Michalis Economou, Marco Guidarini, Stefano Ranzani, Alexander Vedernikov, Daniele Rossina, Roland Çene, Petrika Afezolli, Bujar Llapaj, Howard Williams, Neil Thomson and others.”

This impressive education has certainly paid off, as we experienced last night at the concert.

Both works were played superbly. The piano soloist Angela Szu-Hsuan Wu played what seemed like a technically challenging piece by Rachmaninov with great verve and skill, and deserved the tumultuous applause that followed the performance. After a short interval, the orchestra increased in size, getting ready to tackle “The Rite of Spring”. Olsi mounted the conductor’s stand to face an enormous orchestra. Before commencing the performance, he said a few words about the many challenges that Stravinsky’s work poses the orchestra playing it. For example, he explained that within the approximately 40 minutes that the “Rite” takes to perform, there are well over 400 changes of time signature (measures of rhythm). Then, he asked a horn player to play various versions of a tune that Stravinsky had composed in various versions of his work. After that, the orchestra performed the great work. It was an exhilarating performance. Under Olsi’s direction, the orchestra had the audience spellbound. In such a complex piece of music, so much could have gone wrong, but in Olsi’s hands nothing did.

Listening to music played ‘live’ is so much more satisfying than even the best quality recorded music. The three-dimensional spatial appreciation of the sound in a concert hall, or in the case of last night, in a church, can barely be reproduced with the best of hi-fi equipment. As with live theatre, when attending live music, the audience is somehow intimately engaged with the energy and enthusiasm of the players. After a great performance, such as last night’s concert, I am left feeling both exhausted and exhilarated. Last night’s concert performed by the London City Philharmonic orchestra with Olsi Qinami was no exception to this. If you have not yet experienced Olsi conducting, then it is high time that you get to one of his concerts.

November 3, 2023

Cross cultural fertilisation between India and Europe at Milton Keynes

THE ARTIST REMBRANDT (1606-1669) produced a set of 23 drawings based on Mughal miniature paintings that were created in India in the early 1600s. In her article (see: https://mapacademy.io/what-rembrandt-learned-from-mughal-miniatures/), Shrey Maurya wrote:

“Perhaps the original Mughal miniatures arrived from the Dutch trading post in India. It’s also possible that he encountered the paintings in the collections of wealthy traders and various Dutch East India Company officials, who were his friends and often his clients.”

Shrey added:

“These drawings are remarkable for they allow us to understand the incredible global network established by trade ships which allowed an exchange of cultures to take place on a global scale.”

Recently, we visited an excellent exhibition at the MK Gallery in Milton Keynes: “Beyond the Page. South Asian Miniatures and Britain 1600 to now.” Amongst the many beautiful and intriguing exhibits, there were a few that illustrated the influence of Mughal painting on Western European artists. Although none of the above-mentioned Rembrandt drawings were on display, what I saw interested me greatly. I have been long aware of the influence of western artistic trends on the works of artists from the Subcontinent, but not the other way around.

An artist, Willem Schellinks (1623-1678), one of Rembrandt’s contemporaries is represented in the MK Gallery’s exhibition. He, like Rembrandt, is believed to have studied an album of Mughal paintings, which was thought to have been in the possession of the English art collector Alethea Howard (1585-1654), Countess of Arundel, who lived in Amsterdam from 1641 until her death. Incidentally, her portrait was painted by Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). In addition to sketches, Schellinks is known to have painted at least six paintings that contain Indian imagery (see the detail above). One of these and a sketch are on display at the MK Gallery.

In the same room as the Schellincks works, there is a painting by William Rothenstein (1872-1945). Drawing inspiration from traditional Mughal miniature paintings in the India Office Collection (in London), he created his “Sir Thomas Roe’s embassy to the court of Jahangir”, which was completed in 1924.

Before seeing the exhibition at Milton Keynes, I knew that Rothenstein had an interest in Indian culture. For example, he helped Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) to find accommodation in Hampstead’s Vale of Health in 1911-1912, but the well-produced exhibition catalogue provided me with information that was new to me. For example, Rothenstein had visited India and was a collector of Rajput paintings and drawings. In addition, in 1910 he was a co-founder of the India Society of London, whose aim was to bring Indian Art, in its many forms, to the attention of audiences in Britain and the world. So, it is maybe unsurprising that he chose to paint his picture of Sir Thomas Roe (c1581-1644) meeting with Emperor Jahangir (1569-1627) in a style that was influenced by the painters who would have around at the time of that historic rendezvous, sometime between 1616 and 1619.

Close to Rothenstein’s painting, there is an image by Abanindranath Tagore (1871-1951), who was a nephew of Rabindranath Tagore. This chromolithograph, “The Last Moments of Shah Jahan”, was created in 1903 in the style of traditional Mughal miniature painting. It is interesting to note that Abanindranath had never encountered Mughal paintings until he was in his twenties. He was introduced to them by another of the founders of the India Society, the art historian Ernest Binfield Havell (1861-1934). Havell had served the Madras School of Art as Superintendent for a decade from 1884, and in 1896 became Superintendent of the the Government School of Art in Calcutta. According to Wikipedia:

“Havell worked with Abanindranath Tagore to redefine Indian art education. He established the Indian Society of Oriental Art, which sought to adapt British art education in India so as to reject the previous emphasis placed on European traditions in favour of revivals of native Indian styles of art, in particular the Mughal miniature tradition.”

The works by Schellincks, Rothenstein, and Abinindranath Tagore, all on display at the MK Gallery, vividly demonstrate the cross-cultural fertilization that began when Europeans first set foot on Indian soil with intentions that were far from being cultural. I have written about only a few of the wonderful exhibits in the show, but all of the others on display are not only beautiful but are filled with a wide variety of deep meanings. Of the many exhibitions I have seen this year, the one showing at the MK Gallery until the 28th of January 2024 is by far the best.

November 2, 2023

An infrequently opened church in London’s Bermondsey

AS FAR BACK AS the 8th century, there was a priory in London’s Bermondsey district, just south of London Bridge. Like most other monastic institutions, it was dissolved during the reign of King Henry VIII. By 1296, there was a church close to the monastery, the ‘St Mary Magdalen Chapel’. This was built to serve the needs of the workers in the Priory and Convent of Bermondsey. It was the forerunner of the present church of St Mary Magdalen on Bermondsey Street. Please note that the name is Magdalen, rather than Magdalene.

In 1680, the church was deemed unsafe, and most of it was demolished. The late mediaeval tower was retained, and was encased in plaster, which hides its original surfaces. By 1690, a new church had been built. This incorporated the old tower, and is what can be seen today. There were a few later modifications made to the edifice, but most of what one sees, is how it was in 1690. The church was damaged both in WW2 and in a fire in 1971, but it has been faithfully restored. The wood carvings on the reredos beneath the Victorian stained glass eastern window might well have been created by the famous wood carver Grinling Gibbons (1648-1721), who was born in Holland and died in London.

The church feels spacious inside. We were lucky to have been able to enter it because apart from Sunday mornings, when a service is held, it is only open to the public between 12 noon and 2 pm on Fridays. We entered at about 1.45, having just eaten a tasty Vietnamese meal at the nearby Caphe House on Bermondsey Street.

November 1, 2023

Getting into the manor house in Hounslow at long last

WE FIRST VISITED the grounds of Boston Manor in the London Borough of Hounslow in April 2021.

Plenty of covid19 restrictions were then in force and the old Jacobean manor house was inaccessible both because of the pandemic and also because the building was undergoing extensive restoration works. We were able to enjoy the lovely grounds that surround the manor house. In July 2022, long before the manor house’s restoration was completed, I published my book about west London, “BEYOND MARYLEBONE AND MAYFAIR: EXPLORING WEST LONDON”, and included a chapter about Boston Manor. Here is a part of this chapter:

“… the name Boston is derived from an older name ‘Bordeston’, which comes from the word ‘borde’, meaning ‘boundary’. Another etymology of the name, which is unrelated to that of the Boston in Lincolnshire, is that it derives from the name of a Saxon farmer named ‘Bord’. Whatever the origin of the name, Boston Manor, the house, and its lovely gardens (now known as Boston Manor Park), which reach the bank of the River Brent, stands on the border between Hanwell and Brentford.

Until the Priory of St Helens in Bishopsgate (in the City of London) was suppressed in 1538, the Manor of Bordeston was owned by it. King Edward VI granted it to Edward, Duke of Somerset (1500-1552), Lord Protector of England during the earlier part of his reign, and later, it reverted to the Crown. In 1552, Queen Elizabeth I gave the manor to the Earl of Leicester, who immediately sold it to the merchant and financier Sir Thomas Gresham (c1519-1579). After several changes of ownership, the property was sold in 1670 to the City merchant James Clitherow (1618-1682). The new owner demolished much of the existing manor house. He modified and enlarged Boston House, which was originally built in the Jacobean style by Lady Mary Reade in 1622, widow of Gresham’s stepson, Sir William Reade. This house with three gables still stands (but was closed when I visited it during April 2021 because it was undergoing extensive repairs). It looks out onto grounds planted with fine trees, many of them Cedars of Lebanon. The grounds, which include a small lake, slope down gently towards the River Brent.”

Today, the 26th of October 2023, I revisited Boston Manor. Fortunately, the Jacobean manor house’s restoration had been completed. After enjoying coffee in its fine café and walking around the grounds ( part of which is beneath an elevated section of the M4 motorway), we were able to enter the manor house. Visitors are allowed to wander freely through rooms on the ground and first floors. Each room is identified by informative labels. In one of the rooms, there are portraits of several members of the Clitherow family. One was painted by Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723), and another by George Romney (died 1802), who lived in Hampstead for a few years at the end of the 18th century. Several of the rooms have beautiful three-dimensional plastered ceilings. These have been restored well to look like they must have done when they were first installed. Reproductions of the original wallpapers line many of the walls and the grand staircase. The reproductions were based on the few fragments of the original wall papering that were discovered. A couple of wall panels have large expanses of original wallpaper that have survived the passage of time. Although the manor house was stripped of the Clitherow’s furniture long ago, Hounslow Borough Council have restored the rooms magnificently.

Boston Manor house is not nearly as architecturally exciting as its neighbours Osterley House and Chiswick House, but it is older than them, and in good condition. I feel it ought to become as well known as the more frequently visited stately homes nearby.

My book about west London is available as a paperback and a Kindle from Amazon websites such as follows:

October 31, 2023

A memorial to a lost artist at the Tate Britain art gallery

GRENFELL TOWER IN west London went up in flames on the evening of the 14th of June 2017. At least 72 people died in the conflagration. Amongst those unfortunates was the Gambian-British artistic photographer Khadija Mohammadou Saye (born 1992).

About a month before she died, she met the painter Chris Ofili (born 1968) in Venice (Italy), where they were both exhibiting their works.

In 2023, the Tate commissioned Ofili to create an artwork to decorate the grand north staircase of the Tate Britain. According to the Tate’s website, Ofili:

“… considered the significance of painting directly onto the walls of a public building and wanted to choose a subject that affected us as a nation. ‘Requiem’ is a dream-like mural, resulting from his poetic reflections.”

Ofili said:

“I wanted to make a work in tribute to Khadija Saye. Remembering the Grenfell Tower fire, I hope that the mural will continue to speak across time to our collective sadness.”

“Requiem” covers three of the staircase’s large walls. On the middle wall, there is a portrait of the artist Khadija Saye. The website explained:

“Artist Khadija Saye is at the centre of an energy force, high up on the middle wall. She represents one of the souls. She holds an andichurai (a Gambian incense pot) to her ear, in a pose taken from her own artwork. This object was precious to Saye, as it belonged to her mother. It symbolises the possibility of transformation through faith, honouring Saye’s dual faith heritage of Christianity and Islam.”

At the top of the stairs, there are panels explaining the wall paintings. There is also one of Ms Saye’s photographs. Called “Andichrai”, it is from a series of photographs she created in the last year of her life. The photograph, which is a visually intriguing artwork, shows a woman holding an andichirai to her ear, It looks as if Ofili used this photograph to create his image of Khadija in his “Requiem” mural.

When I first looked at Ofili’s “Requiem”, I was reminded of the dramatic images of William Blake (1757-1827). It is a wonderful memorial to an artist, who was cut-off in her prime. I do not know how long “Requiem” will remain on the staircase at the Tate. So, I recommend that you go and see it as soon as possible.

October 30, 2023

The artists John Mallord Turner and Mark Rothko and abolition of slavery

AFTER BEING DISAPPOINTED by the large temporary exhibition of playful but repetitive works by the artist Sarah Lucas (born 1962) at Tate Britain, we had a coffee and then revisited the rooms containing paintings and sketches by John Mallord Turner (1775-1851). It has been many years since we last viewed these paintings, and seeing them revived our spirits after having had them somewhat lowered by the Lucas exhibition.

One of the Turner galleries contains a particularly fine painting by the American artist Mark Rothko (1903-1970). It hangs amongst a series of Turner’s often unfinished late experiments on canvas. They were mostly items found in Turner’s studio after his death. Without outlines, these almost ethereal paintings are examples of the artist’s experimentation in ways of depicting light and colour. If one did not know when these works were created, one might easily guess that they are the works of an artist working during the age of Impressionism. As an aside, many of Turner’s finished works are extremely impressionistic, and I consider him to be the pioneer of what later became Impressionism, and one of the best creators in this style. These experimental works were displayed at an exhibition in New York City at its Museum of Modern Art in 1966. That year, Rothko remarked:

“This man Turner, he learnt a lot from me”.

The Rothko painting hanging amongst the Turner experiments was created in 1950-52. Later, in 1969, Rothko donated a set of his paintings to the Tate, hoping that they would be hung close to those of Turner. They are not; they are hanging at the Tate Modern.

Moving away from the room in which the Rothko painting is hanging, I came across another Turner painting that interested me, “The Deluge”, which was first exhibited in about 1805. In the bottom right corner, Turner has painted a black-skinned man rescuing a naked white woman. On close examination, the man can be seen to have a chain around his waist. The Tate’s caption to this picture includes the following:

“Painted at a time when the cause for Britain to abolish its enslavement of people of African descent was gaining ground, this detail is significant.”

Some years after it was painted, Turner gave a print of this work to a pro-abolition Member of Parliament.

“The Deluge” is not the only painting by Turner relating to his sympathy for the abolition of slavery. His “The Slave Ship”, first exhibited in 1840, is another powerful example. This painting, now in Boston (Massachusetts), is based on the dreadful incident when, in an attempt to cheat the insurers, the captain of a slave ship, the Zong’, caused 132 slaves to be thrown overboard (in 1781). Turner had learned about this crime from the anti-slavery activists with whom he associated. Although Turner, a liberal, was sympathetic to the abolition of slavery, he was not totally divorced from the benefits that transatlantic slavery brought to Britain, as was pointed out by Chris Hastings in the “Mail Online” on the 28th of August 2021:

“One of Britain’s greatest painters has fallen victim to woke culture, as art-lovers are being warned not to ‘idolise’ J. M. W. Turner because he once held a single share in a Jamaican business that used slave labour.”

The website of London’s Royal Academy gives more detail:

“It would be fair to assume that Turner’s views were strongly pro-abolition at the time he painted this work. However, scholars have pointed out that earlier in his career he apparently had no qualms about investing in a company that ran a plantation … In 1805 Turner invested £100 to buy a share in a business called Dry Sugar Work. Despite the name, this enterprise was a cattle farm on a Jamaican plantation run on the labour of enslaved people. The business was owned by Stephen Drew, a barrister who bought the estate from William Beckford in 1802. The firm went bust in 1808.”

Some many months ago, we saw a play at the National Theatre, “Rockets and Blue Lights” (written by Winston Pinnock). It concerns an ageing Turner seeking inspiration from a remembered incident like the awful event that took place on the “Zong”. During the play, it was alleged that because of his disgust with the slave trade, Turner gave up using sugar. Whether or not this was the case, I cannot say.

Fascinating as are abolitionist and the Rothko ‘connections’ with JMW Turner, the well-displayed paintings in the Turner galleries are all superb and well worth visiting.