Thomas E. Ricks's Blog, page 73

December 9, 2013

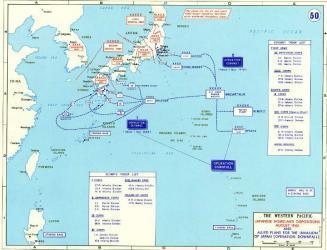

We should make Nov. 1 a national holiday

Speaking of Pearl Harbor Day, why not

make November 1 an annual holiday? That was the day in 1945 that President

Truman had selected for the beginning of the American

invasion of Japan. We all should be glad it never had to

happen.

December 6, 2013

Tom reviews 'The Cambridge History of War, Vol. IV: War and the Modern World,' and learns a whole bunch of new stuff

This is a pretty amazing book. If it were priced

reasonably, rather than insanely, I'd recommend getting it just for the table

of contents, the footnotes, and the bibliographies.

And there is lots to like in the book's 26 essays, which

cover from the mid-19th century to today. The speed of this ambitious romp

through history is sometimes breathtaking. The American Civil War, for example,

gets three pages. The Spanish Civil War gets a page or two in one essay, five

more in another. (Btw, I didn't know that roughly half the Spanish army, and 70

percent of its generals, sided with the Republic against Franco's rebellion.)

And this book isn't just about wars -- it is about doctrine,

PoWs, culture, military occupations, the effects of decolonization, and so on.

Even Hogan's Heroes gets a shout-out.

To cover all that, you need to move through history fast, distilling a lot of

information and so sometimes launching some pretty big assertions. Geoffrey

Wawro, discussing technology in the pre-World War I era, writes that, "The

great, blinding conceit of modern armies was that they could win by pluck and

morale."

I didn't like the occasional bouts of academic jargon in

Eugenia Kiesling's essay on "Military doctrine and planning in the interwar

era," but I was taken by some of her observations on military culture in that

time. She detects in the Japanese army before World War II "A culture that

justified insubordination, if it was committed in the name of Japan's warrior

spirit," which "led junior officers from the army to murder a prime minister in

1932 and to attempt to overthrow the government in 1936." Likewise, she sees in

the U.S. Army of that time "additional evidence that in shaping technological

choices, institutional culture tends to trump both strategic vision and

operational planning."

It also is amazing to me that there is always more to learn.

For example, I've read hundreds of books on World War II, but I did not know

that as "late as 1938, about half of U.S. light artillery was horse-drawn." Nor

did I know that the climactic battle of the Chinese civil war, in late 1948,

was the biggest battle between the end of World War II and the beginning of the

Iran-Iraq War in 1980.

Gerhard Weinberg also does a masterful job of summarizing

all of World War II, Europe and Asia both, in 32 pages. How? In part by

summarizing entire campaigns in just a few succinct lines. Here is how, in

three sentences, he explains why the Pearl Harbor attack was a failure on three

levels -- strategic, operational, and tactical:

First, by ensuring the Americans would insist on a crushing

victory, it destroyed the Japanese concept of making extensive conquests and

then arriving at a new settlement. Second, the shallow waters of Pearl Harbor,

of which the Japanese were aware, meant that most of the warships that Yamamoto

imagined sunk were instead set into the mud, raised, repaired and returned to

service. Third, the attack on ships in harbor on a peacetime Sunday failed to

eliminate the crews of most of the ships.

Tom again: One downside to the book is that these are

academics writing, so sometimes you get sentences such as, "This chapter looks

beyond this narrative and telos of World War II in three contexts." (In

academia, "narrative" seems to be a bad thing, a snide putdown like

"conventional," and almost as contemptible as "popular history." I don't understand

why, as narrative is the most human of traits -- it is how we make sense of the

world. Anyway, I'll see you a telos and raise you a conatus.)

Footnote for those who believe the British generals of World

War I have been cleared of the donkey charge by recent research: Michael

Niberg, in his overview of World War I, concluded that the British were

"unimaginative" at Passchendaele and risk-averse after Cambrai. He also makes

the interesting observation that "casualty rates were higher during periods of greatest

mobility."

Still, a lot of fun, if you can persuade your library to buy

it.

Quote of the day: General Trainor on the loneliness of today's new veterans

Retired Marine Lt. Gen. Bernard

Trainor (and author, too) looks back at

his returns from wars in Korea and Vietnam and discerns a major difference in

the world today's vet finds when he comes home:

Today's all-volunteer soldier is alone; very

few of his peers have served in the military, much less gone to war. Rarely are

there guys to hang out with at a Manion's. Earlier, the American Legion, the

VFW and reunions were a refuge of comradeship. But those are dying

institutions, and today's veteran is not a joiner anyway. He is largely

isolated, with only his iPhone as a comrade. Wounded or whole, modern veterans

speak of yearning to be back with their units, no matter how unpleasant it

would be. Many feel alone, no longer a member of Henry V's "band of brothers."

Rebecca's War Dog of the Week: A boost for Navy dog handlers

By

Rebecca Frankel

Best

Defense Chief Canine Correspondent

The Marine Times reported this week that "[t]he Navy's

Center for Security Forces is in the final stages of creating the first

apprenticeship trade program for those with military specialties that involve

working dogs." If the Department of Labor approves the program, it means that

that "hundreds" of MWD handlers in both the Navy and the Marine Corps will be

eligible for apprenticeships that will not only potentially "boost [their]

military career, but also help [servicemen and women] land a law enforcement

gig" after they retire from the military, say with a police department K-9 unit

or with a private security company.

This is especially encouraging

news as many retiring military servicemen and women are finding it difficult to

find jobs in the civilian workforce. The Washington

Post reported in November that the "unemployment

rate for recent veterans remains incredibly high -- around 10 percent --

and remains noticeably higher than it is for non-veterans in the same

demographic group."

Should this new program receive

the expected approval, it will, says MA Jose Bautista, programs manager at the

Navy's Center for Security Forces, offer "concrete documentation of your skills

and experience, and that's what selection boards love to see. That same

documentation enhances someone's marketing potential in the civilian workforce

when their military service is complete for the same reasons. I've seen many

apprenticeships on the résumés of senior enlisted sailors who've walked out of

the Navy's door into very good civilian careers."

And for many handlers, this is

good news for handlers for another reason entirely: Life after the military

doesn't have to mean a life working without dogs.

Above,

MWD Rex, of Naval Air Facility Atsugi Naval Security Force, lays

on the deck of a MH-60S Seahawk helicopter during an aerial training exercise

for K-9 units. Rex and his handler are participating in readiness training for

future deployments through accumulation of scents, movement, and the feel of

riding in, and being around helicopters.

Rebecca

Frankel is special projects editor at Foreign Policy.

December 5, 2013

Lessons of 1940: The hardest decision might be the persuasive one, while a disaster might lead to later success

Those are thoughts

that occurred to me after reading about Churchill's decision in the summer of

1940 to attack the navy of France, which had been an ally just a month earlier,

and which certainly was not at war with the United Kingdom. More than 1,200

French sailors were killed in the attack, while the British suffered two dead.

The purpose, of course, was to prevent the French fleet from falling into German

hands (as had happened with Austrian gold and Czech weapons factories).

President Roosevelt,

knowing how difficult a decision it was to launch a surprise attack against a

former ally, was said to have calculated that his defeatist ambassador to London,

Joseph Kennedy, was wrong, and that in fact Britain was determined to fight on

alone. (Speaking of FDR, it took me a while to remember the names of his three

vice presidents, but eventually I did. But for the life of me I couldn't

remember who Truman's veep was, and had to look it up.)

On the other hand, I

was interested to read in Cambridge History of War, Vol. IV: War

and the Modern World that one reason the Germans couldn't invade England later

that same summer was because of their naval losses the previous spring in

fending off the British attempt to take Norway. "While the victory of the

British in the Battle of Britain was won in the air," Gerhard Weinberg writes

in his fine essay on World War II, "the German failure to attempt an invasion

was due at least as much to their naval losses in the Norwegian campaign."

That British attack

on Norway long has been regarded as a disaster. Reading about its beneficial

effect on the Battle of Britain makes me think that Churchill may have been

right in his view that in conventional warfare, doing something, even at the

periphery, is always better than doing nothing at all.

As Bob Dylan or Clausewitz once

observed, nothing is easy in war, because friction makes even easy things

difficult.

What means this 'wind down' a war?

The editor's page in the November issue

of Proceedings begins with the phrase

"As the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan wind down...."

Putting aside the fact that the war in

Iraq is not winding down, and no hit on Proceedings

editor Paul Merzlak, what does that phrase mean? I mean, we all use it. I think

I have used it, and I know some of youse have in comments on this page (because

I checked).

As I read it, it occurred to me that this

phrase has become very popular in the last couple of years, but I have no idea

what it really means. If I had to guess, I'd invoke T.S. Eliot:

This is

the way the world ends

This is

the way the world ends

This is

the way the world ends

Not with

a bang but a whimper.

Almost like we just got bored with our

wars.

Outside the drawdown and looking in

By

Emerson Brooking

Best

Defense guest columnist

Although the drawdown has left scars across

every level of the armed services, it poses some of its biggest challenges for

those at the start of the commissioning pipeline. Rapidly decreasing numbers of

slots, a surplus of qualified candidates, and a universal lack of information have

combined to make today's application process deeply uncertain. Many strong

applicants -- shoo-ins just a few years ago -- must now try repeatedly for a

ticket to OCS, effectively putting their lives on hold. Many still will not

make it. The situation raises tough questions without good answers.

I've watched this process unfold as both a

Marine Corps applicant and an active observer to discussions surrounding

defense budget reductions. Officer wannabes struggle to stay free of doubt as

they put their spirits into commissioning programs that could abruptly cease to

exist. Meanwhile, grim numbers thrown around by policymakers suggest that the

situation will likely get worse before it gets better. While my experience is

specific to the Marine Corps, I suspect the story is similar for folks on the

Army side.

Anonymous forum boards like Marine

Corps OCS provide a window into the mindset of today's aspiring candidates.

Amid standard topics like pull up techniques and essay tips can be found a

growing number of discussion threads that reflect more fundamental

concerns: Could my application ever make it? Will there even be slots

available? At what point should I stop trying -- and what could I possibly do

instead?

When applicants' final packets have been

submitted for consideration, they often post their "stats": their

school of graduation, their PFT, their GPA, number of waivers, and status of

their recommenders. This is done both for the benefit of the community and for

the aspiring candidate's own peace of mind. It's difficult to read these posts

and not think immediately of sites like College

Confidential, where stat-filled "chances" threads provide elite college

applicants an opportunity to measure themselves against the competition.

Between each of these worlds, the same earnest motivation bleeds through. So

does the same numb despair when word of rejection arrives.

While the college analogy provides a good

fit for today's officer selection process, there's a crucial difference. This

is an admissions process in which even basic information like average scores

and acceptance rates remain hidden from view, and where the number (and even

existence) of some commissioning program slots can change overnight. Only the

broad trend is clear: steeply rising standards and rapidly shrinking odds.

There are numbers of truly qualified

candidates -- exemplary leaders, fitness gods -- who have now thrown themselves

several times through the application cycle without success. In the interim,

many effectively put their lives on pause, drifting from one job to the next

while reserving the start of their real career for the Corps. With the defense

budget continuing to deflate, they may never get a shot. It's an open question

what these "could-have-beens" will pursue in place of service. In any

case, one suspects the really serious ones won't talk about it much.

Emerson

Brooking has worked as a journalist and is currently a DC-based defense

researcher. He's just signed up for his first marathon and would welcome

training tips at

etbrooking@gmail.com

.

December 4, 2013

Bob Dylan knew what he was talking about when he wrote 'Masters of War' -- plus his thoughts on Army recruiting!

I noticed the other day with surprise

that Bob Dylan's website lists among books that influenced him Clausewitz's On War. I wonder if there are any other

pop artists influenced by that book? Maybe Eric Burdon or Edwin Starr?

What is weird is

that as I typed this, a Bob Dylan song came on the radio -- "Rainy Day Women,"

which I don't even like. Btw, he isn't just an icon of the ‘60s. There are a

ton of Dylan songs over the last 20 or 30 years that I think are great and

should be better known -- "A Sweetheart Like You" (which I think is about an

assistant to Lucifer talking to a morally lost woman), "Jokerman"

(which I think in part is Dylan talking about himself, and about other false

idols), "Working Man Blues No. 2" (with its refrain about

fighting on the front lines), and another recent song, "Thunder on the

Mountain," which speaks to the issue of military personnel with a neat rhyme:

Gonna raise me an army, some tough sons of bitches

I'll recruit my army from the orphanages

Well, it works the

way he sings it.

PS -- While we are

on the subject of music, you should check out . Good music, no ads. I used to

listen to it while in Baghdad to get my mind off the war. Now that I think of

it, it is kind of ironic -- being in Hell but listening to the music of

Paradise.

Quote of the day: The significance of Cantigny for the U.S. military and nation

From a book review

by Mark Grotelueschen in the October issue of The Journal of Military History:

Although the

infantry assault was conducted by just one reinforced regiment, the attack was

supported by the rest of the 1st Division (itself nearly half the size of Lee's

entire army at Antietam), thirty French aircraft, a squadron of French heavy

tanks, a section of French flamethrower troops, a wide variety of

communications technologies, and over 250 pieces of French and American artillery (about a hundred more than Lee used to support Pickett's Charge at

Gettysburg), Cantigny truly was the U.S. Army's baptism into modern battle."

I'd never thought of

it that way, partly because it is hard to judge by reading first-person

accounts, which is mainly what I read when, as research for my book The Generals, I was looking at George

Marshall's experience in World War I.

Arkin: Hey dumbasses, it's not Vermont you have to worry about, it's the country

Bill Arkin, a man of his convictions,

has the heart & soul to take

his fellow Vermonters to task about where to base

F-35s:

The

roar of F-16s or F-35s might rupture the peaceful image of Vermonters, nice

people who think that they can create some sanctuary and drop out of the

national tragedy. They should spend their energy instead going to war against a

national security system that can no longer police itself, and one that no one

in Washington has any intent of changing.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 437 followers